Abadan and Khorramshahr, Iran

The histories of some cities are coiled with symbols, legends, economic upheavals, political revolutions, colonial occupations, and such like. The two cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr in the south-western Iranian province of Khuzestan are no exceptions. Both display a hybrid identity which has been forged out of global oil interests and acts of local cultural resistance. Add to this mix their unique climate conditions and the cultural practices of local people, as well as the often confusing old street patterns, and you’re in for a treat. The two river ports of Abadan and Khorramshahr – sitting not far downstream from Basra in Iraq – lie on the Arvand River, often referred to as Shatt Al-Arab, this being the Euphrates/Tigris confluence as it flows into its delta at the northern end of the Persian Gulf.

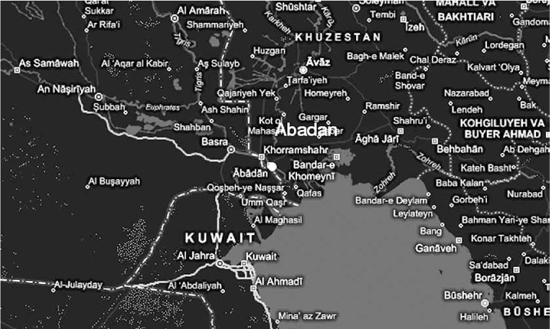

11.1 Map of Abadan and Khorramshahr on the border with Iraq and close to Kuwait

Abadan hence sits 60 km north of the Gulf shoreline. In terms of its local geography, the city is bounded by the Arvand River on its south-to-southwestern sides, this forming the Iraqi border, and by the Bahamnshir outlet of the Karun River on its north-to-north-western edges. Flowing off in the southwesterly direction is the aforementioned river to the Persian Gulf. Khorramshahr is the somewhat overshadowed neighbour just 15 km the north-west, and indeed they could on the surface be regarded as a kind of ‘twin city’. However, this would be to miss their subtleties. While the historically iconic cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr are geographically so close they remain so different in their cultural practices, urban fabric, housing types and political symbolism. Abadan remains easily the larger of the two, with a current estimated population of around 220,000 persons, compared to just 124,000 in Khorramshahr. Some argue that these differences and the contradictory historical journeys which the two cities have taken – in terms of urban structure, cultural identity and everyday habits – in fact make them complementary. Others might see the links merely in terms of having the same climate, an equal denial of past practices, and thus a casual attitude towards consuming and wasting energy. A closer look at the political history and human habitation of these two fascinating cities on the northern rim of the Persian Gulf offers clues as to how oil-rich cities are shaped both by local climate and the brutal pressures of the global market economy. The presence of oil in this area, especially in Abadan, has totally dominated the lives of local citizens and been instrumental in destroying its older, more climatically responsive, built fabric. An exploration of these tensions will form the substance of this chapter, following a brief background introduction.

THE ARRIVAL OF AMERICAN/WESTERNISING TENDENCIES

Abadan and Khorramshahr both grew steadily in importance after the discovery of oil and gas reserves. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company built its first refinery in Abadan in 1909–1913 and by the 1930s this was the largest in the world. Growth continued to boom after the Second World War, such that for a few decades Abadan was the largest oil-producing city anywhere; Khorramshahr played the role of an important supporting act. More recently, the urban development of Abadan and Khorramshahr has been shaped by their geographic location close to the borders of a number of oil-producing Gulf countries, notably with Iraq to the west and Kuwait to the south-west.

11.2 Abadan oil refinery in the early-1950s

Both cities thus became extremely active economically during the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979), and during the latter stages of which Iran’s oil income soared from $22.5 million in 1954 to over $19 billion in 1975–1976.1 This staggering increase in oil revenue however brought little benefit for local citizens. The economic gap between the local majority and a transient wealthy minority (mainly Americans and Europeans) had become chronically unfair by the end of the 1970s. This situation also needs to be set within the major geopolitical changes of that era. Iran’s oil supplies and its strategic location, adjacent to what was then the Soviet Union, now Russia, were vitally important to the USA at all levels. This ‘invasion’ of Iran by the global market first began to be truly noticeable during the 1960s in all industries and in people’s everyday lives. As Hamid Naficy explains in his essay on new Iranian cinema of that era:

Regional media influences in Iran were replaced by global interests. American companies began selling all kinds of products and services, from feature films to television programmes, from TV receivers to TV studios, from communication expertise to personnel training: in short, they sold not only consumer products but also consumer ideology.2

Naficy continues by noting that the first Iranian television station, which was commercially based and privately owned, was established by Iraj Sabet, whose family also happened to be the agents for Pepsi Cola and various US advertising agencies. The new channel imported American programmes as well as dictating all the commercials broadcast on Iranian TV. By the late-1960s and early-1970s, products like Pepsi Cola and Winston cigarettes became a lifestyle image and a symbolic representation of the ‘western‘ world for Iran’s upper and middle classes.3 Indeed, what was particularly alarming about the arrival of American consumer products was their close association with the culture of pleasure being enjoyed by workers and middle-income groups. When the first Pepsi Cola factory opened to the west of Tehran, with its glazed façade exposing the process of bottling the drink, many working-class families went for picnics in front of the Pepsi factory rather than to their usual local park! This intrusion of ‘brand’ culture and its metaphor of American/westernised desire was vividly described in the work of the controversial female Iranian poet, film-maker and writer, Forugh Farrokhzad (1935–1967). In a poem of 1965 titled Someone Like No One Else, she wrote beautifully of her memories as a child.4 Farrokhzad was one of the most unconventional and sharpest commentators on the socio-cultural transformations being experienced in Iran at the time, bringing in references to everyday mass culture in her work.

The arrival of the American consumer culture and its glittery products primarily benefitted Iran’s elite minority, creating a huge economic and cultural gulf with the rest of Iranian society. This was not only visible and tangible in Tehran, Iran’s modern capital, but if anything was probably even more representative of and reflected in cities like Abadan and Khorramshahr. Economic inequality, exploitation of local workers, and privileges given to expatriate Europeans and Americans can be seen in some of early Iranian movies. Most notable was the Abadani director, Amir Naderi, in his masterpieces ‘Tangsir’ (1973) and ‘The Runner’ (1985); both films are set in Khuzestan, where the sheer depth of oppression and local anger was bravely and masterfully documented in these films.

Importantly, Khorramshahr and (more specifically) Abadan played critical roles in the movement to nationalise Iran’s oil industry in the early-1950s, as well as at the decisive moments of victory by the Islamic Revolution over Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1978–1979.5 Indeed, it is argued that the two key events that were the turning point for the Iranian Islamic Revolution were the oil-workers’ strike in December 1978 and the burning down of the Rex Cinema in Abadan on ‘Black Friday’ in August 1978, with over 350 people killed in the fire. However, after this featuring role for Abadan and Khorramshahr in the late-1970s – with their heroic fight against the Shah’s dictatorship and its appalling human rights record – came the devastating physical, human and economic sufferings and losses which both cities experienced during the Iran/Iraq War (1980–1988).6 Even after eight years of fighting and occupation by Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Army, backed by America and France, neither Abadan or Khorramshahr ever gave up. Instead, both cities managed to resist until the Iraqi forces were driven out, with the result that they – and this time around even more so in Khorramshahr’s case – became the symbol (and indeed reality) for yet another historic Iranian achievement.

Yet despite contributing such rich layers of political and economic meaning within the socio-political fabric of Iran, neither of these two cities was rewarded with much attention or indeed resources with which to celebrate and share its historical importance with local citizens or tourists. Their unique urban planning, spatial characteristics and architectural details – which collectively offer a platform to discuss the relationship of climatic context and cultural identity to models of habitation – are likewise underappreciated, indeed even ignored. Rather, one needs to rely on undocumented local knowledge provided by the older generation of citizens still living in the two cities, often in a sad state of affairs; bizarrely, many older residents adhere to the myth of the pomp and glitter of ‘the good old days’, even if only for a few elite groups, back in the Pahlavi era. It is therefore important to transcend this condition of historical amnesia and urban neglect by looking more carefully at Abadan and Khorramshahr to find out how people might live in the northern part of the Persian Gulf. However, given that Abadan has for so long been the ‘dominant twin’, the bulk of analysis in this chapter will by necessity focus on it.

CITYSCAPE

Abadan lies on what is in effect an encircled island of 63km in length and from 3–19 km in width, abutting onto the Arvand River or Shatt Al-Arab. Looking from a bird’s-eye perspective when flying in from Tehran, one is fascinated by the regularity of the agricultural land around Abadan. The well-mannered forest of date palms – which still provide a sizeable percentage of world’s dates – hugs the city to its northern, eastern and western edges, giving it protection from the desert beyond. It is an unexpectedly pastoral image, given that Abadan is barely known for anything but its oil resources.

The airport to the north-west, just like the main railway station, is a facility shared equally by Abadan and Khorramshahr. On stepping out of the plane, one immediately feels the pleasant dry heat – that is, if you take care to avoid arriving in summer at any time between 12.00 noon and 6.00pm, when temperatures are usually in the mid-40s°C. During these ‘boiling’ hours in the summertime, when the heat becomes unbearable, you will hardly find anyone around; indeed, the airport itself is closed. However, in the months from November to April, local temperatures become far more agreeable.

In contrast to Tehran, Abadan seems extremely calm and polite. There is a surprising absence of any smell of oil/petroleum, the very thing that modern Abadan is famous for. The city’s history predates Islam back to the Sassanid dynasty (224–651AD). Written legends suggest that Abadan was initially known for its salt deposits and mat-making crafts, and it later grew into an Islamic port city during the great Abbasid Caliphate. In Iran, there is never any shortage of legends and unofficial stories which offer more tangible insights into the life of cities than written histories do. Hence it is believed that the Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali (his son-in-law and Islam’s first spiritual leader) somehow made references to Abadan as a place of paradise where ‘palm gardens and mosques come together making it ideal – ‘God’s creation’ – as a place of rest for Hajji’s, visitors to Mecca, to stay’.7 Here is important to note that soon after Islam was born, a regular movement by Hajji pilgrims took place from Iran across the Euphrates/Tigris River to the Saudi cities of Mecca and Medina. Thus a city like Abadan, positioned on the edge of a river in the desert, also offered a perfect stopping point for Muslim travellers.

The already mature tradition of Iranian urban architecture, based on private mansions, gardens and courtyards, was readily adapted to the new demand to build Islamic mosques. With a central pond celebrating the role of water – an element used as a practical response to the hot climate and hence a staple of songs, poems and daily cultural rituals – the insertion of mosques into gardens was yet another variation on the Persian garden/courtyard typology. Indeed, the mosque came to replace the private mansion as the pre-eminent urban form, with the side benefit also of making traditional Persian gardens more socially inclusive. Hence for the Prophet Muhammad and the new Islamic leaders, the fusion of the emerging mosque typology with a sophisticated form of urban space served as a symbol of the new Islamic paradise-on-earth, as well as fitting easily into climatic conditions and cultural practices. Some of these very early mosques and garden courtyards are still visible in and around Abadan. Sadly, however, Abadan in later centuries has lost this urban continuity. Now, and certainly for the younger generation in the province – as indeed in the rest of Iran – the city is explicitly conceived of in terms of oil/petroleum income and the struggle of the Iran/Iraq War, rather than for its older tradition of shaded gardens, waterways and climatically responsive buildings.

11.3 Flames of the oil refinery and petrochemical complex dominating Abadan’s skyline

CITY OF FLAME: ABADAN AND OIL/PETROLEUM

The National Iranian Oil Refining and Distribution Company (NIORDC) and the connected National Iranian Petrochemical Company (NIPC) serve to divide Abadan visually and physically from west to east. Incredibly, the floor area of both plants occupies nearly a third of the city’s area. So these are the two elements which constantly remind citizens of the presence of global forces in Abadan. Whenever one drives or walks around the city, the flames of the oil refinery and the petrochemical complex are always there, dominating the place from all directions.

It is worth here tracing the story of the oil industry in Abadan to see how this situation arose. Back in 1905, the whole region was indirectly controlled by British colonial rule, and one symbolic manifestation of this was the formation that year of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. In 1908, oil and gas reserves were discovered in the city of Masjed-e-Soleyman – like Abadan, in Khuzestan province, but further to the north. To be able to export these supplies, by 1913 the Anglo-Persian Oil Company had built a pipeline to its first refinery in Abadan, thereby instantly transforming the latter into a globalised city. As noted, within 25 years Abadan had the largest oil refinery in the world, even if there was still extreme poverty and inequality for most of its local community. Prior to the nationalisation of Iranian oil in the early-1950s, around 80–85 per cent of the wealth created was in British ownership. This contradiction between poverty and elitism remained in Abadan in different forms even after nationalisation, and exists today in different forms. None of the British colonial rulers, nor the Pahlavi regime which replaced them, nor even the subsequent Islamic Republic government, have bothered to explore the climatic wealth and social potential of Abadan. Instead they have just exploited the presence of oil and gas to feed Iran, and the wider world, with little thought about local citizens.

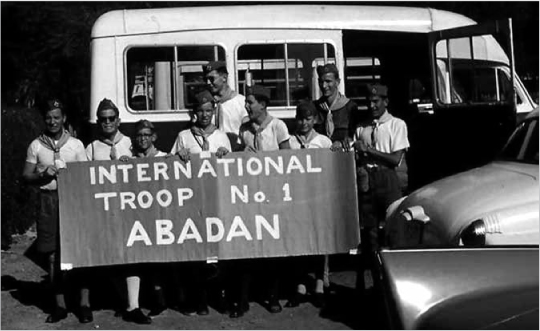

Abadan, as the ‘city of flame’, seems historically to have always been a transient city. Its population increased greatly after the discovery of oil, most of whom were skilled workers and engineers brought in from the rest of Iran, especially Tehran, or else from abroad. It is believed that during its peak from the early-1950s to the mid-1970s, less than 10 per cent of the city’s population came from Abadan or elsewhere in Khuzestan province. The other 90 per cent were from elsewhere, including a large number from Britain, continental Europe or the USA who were only there to work in the oil industry. This transient community was totally unfamiliar with the climatic condition and everyday cultural habits which over the centuries had created such a strong imprint on the urban character and spatial formation of Abadan.8

11.4 American oil-worker families arriving in Abadan

The extensive use of Europeans and Americans for technical and administrative staff was a deliberate policy on the part of British colonial powers to maintain control over the oil industry. This could be graphically seen in 1951 when Iran suddenly nationalised the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Britain immediately imposed economic sanctions and deployed its warships to blockade Abadan and all of Iran’s southern ports. Furthermore, they withdraw all of their technical personnel along with 300 administrators from Abadan. Iran’s counter-attempt to bring in technicians and consultants from other countries proved a failure, forcing it to turn to US support to run the industry.9

Meanwhile, the transient oil community brought its own forms of architecture, urban planning and living habits which in no way related to Abadan or the logic of living in that climate. Its unsuitability was reflected in the street layouts and building types erected during the 1960s and 1970s. Later on, when the city was attacked in 1980 by the invading Iraq Army, it was the non-local oil worker community that was the first to leave, including other Iranians. Moving as far as they could from the war zone, most never came back, meaning that only a few traces of their occupation survive today. I was told by a local shopkeeper who was one of the few from elsewhere in Iran who did return to Abadan:

People went away partly because the government was too busy trying to fight the war, as well as being extremely surprised by the attack, and so they did not provide any protections or facilities for those fleeing from Abadan. But we had to come back; after all, it is our home. This was not the case for Tehranis, who left Abadan and never returned.10

Restoration of full operational conditions at the Abadan oil refinery didn’t happen until 1997, and created renewed economic and employment activities. Once again, however, the oil worker community brought in from other provinces of Iran appears to be a transient one. The Islamic Republican government did introduce a variety of measures, including certain financial incentives, to encourage people to move back to the city to restart the economy. Yet the city of Abadan today seems to consist of displaced souls, with more and more new arrivals from elsewhere in Iran.

There is a mysterious, ominous feel to the oil refinery/petrochemical plant in the way it overshadows the city, rather like in The Castle by Franz Kafka.11 It’s an impossible space to penetrate, literally and metaphorically, so one can only imagine the hidden, bureaucratic layers of power within. Citizens talk about it, mentioning the social divisions created in the Pahlavi era, the money it has generated, the foreign managers and engineers implanted from outside, the way which the city has been designed around it in a secretive and inaccessible manner. The stories one hears from locals about the past and present life of the oil refinery invoke a specific image; as an alien object, this global representation is still untouchable in their minds. Industrial plants constitute a huge part of Abadan’s identity and yet are unable to identify in any meaningful sense with the city’s everyday life.

NON-PLACE?

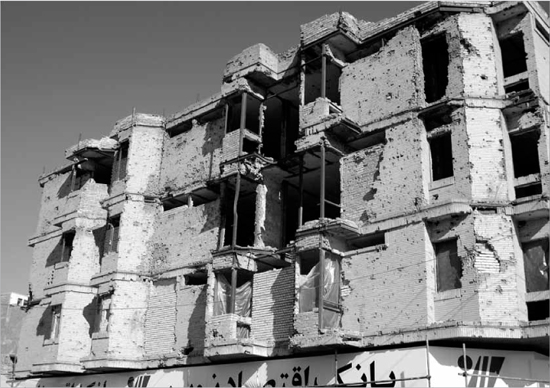

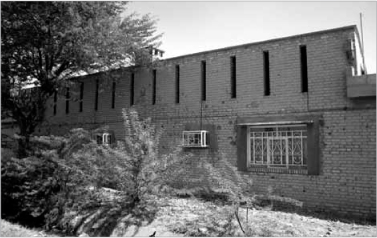

The pattern of continuous immigration and the sudden gains and losses of population make Abadan a service city – perhaps even a ‘non-place’ – within the national and global marketplaces. If there continues to be little attention to how to create a sustainable local community, the problem will simply be perpetuated. What, then, ought to be the physical identity of cities of this kind? Other key issues of cultural identity are also being swept under the carpet. Almost all of Abadan’s southern and south-western borders are shared with Iraq, reminding citizens of the bitter 1980s conflict in which Abadan was under direct siege for 18 months. Driving around the city, almost every taxi driver tells you of their experience of war as if it was yesterday. Half-demolished buildings likewise offer strong reminders of those moments. This psychological presence of the Iran-Iraq War, which ended 23 years ago, is of great concern, and of course the same problem exists in neighbouring Khorramshahr.

A concerted process of post-war reconstruction would have been the ideal scenario for both these war-damaged cities, and indeed a localised, environmentally-driven regeneration programme on socially sustainable lines would have fitted the stated policies of the Islamic Republic government. Hashemi Rafsanjani, who from 1989–1997 was the first Iranian first president after the Iran-Iraq War, tried to push for extensive rebuilding. He favoured private development and free-market investment linked to the newly introduced concept of real estate, echoing to some extent what was happening in Britain under the Thatcher government. But all that has happened since then is a vague promise of establishing a ‘free economic zone’ in Abadan, similar to those in Kish Island or Dubai, which if introduced would simply freeze out local citizens once more and, critically, perpetuate unsustainable forms of development.

11.5 Half-demolished buildings in Abadan as reminders of the Iran/Iraq War, as photographed in 2009

In addition, it is not clear why Iran’s bold reconstruction projects from the 1990s, including a Californian-style oasis – called Arge-e-Jadid12 – created from virtually nothing in the middle of the desert, didn’t touch upon Abadan and Khorramshahr given their historically important locations on the Arvand River/Shatt Al-Arab. There is a very real argument that the cities deserve far more attention and investment than has hitherto been offered to them. They could be turned exemplars of urban reconstruction based on specific climatic conditions, use of natural resources, and ways in which cultural identity is reconnected to urban lifestyles. Similarly, it’s also unclear why some of the bonyads – charity foundations which became devoted to religious purposes following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and also highly effective in redistributing the wealth of the upper-class minority from the Pahlavi era – haven’t been asked to consolidate banks and regenerate empty properties in the Khuzestan region to promote socio-economic reconstruction.13 Instead, large numbers of properties which once belonged to the elite during the Pahlavi dynasty, some of which reflect imported colonial architecture such as from Britain or the Netherlands, remain unoccupied and left to ruin in Abadan and Khorramshahr. Instead, they ought to be reused as prime examples of how to redesign old dwellings for a new cultural context.

11.6 Colonial-style dwellings sit empty and left to ruin in the Bawarda garden suburb in Abadan

11.7 1950s Anglo-Iranian Oil Company dwellings by the British architect, James M. Wilson, in the Bawarda neighbourhood

GOOD AND BAD OLD DAYS – ‘THE THEATRE OF SILENCE’

The contrast with Abadan’s traditional urban layout posed by the dwellings built for oil-workers, with their incorporation of colonial styles in gated communities, only adds to the surreal nature of the city. ‘Alien’ forms of pitched roofs, Arts & Crafts cottages, Art Deco mansions – now mostly unoccupied – hint at a theatrical setting. This however is a ‘theatre of silence’, with little life inside it, as a result not just of the fall in population after the Iran/Iraq War but also the social disconnection of neighbourhoods. Again, this is unfortunate, especially given the vibrancy of Abadan in earlier generations. Indeed, this oil-rich city was the epicentre of political activities in Iran during the 1940s, pushing for workers’ rights and the nationalisation of oil. In March 1946 the British Army, aided by a few sections of Iranian forces, killed over 50 left-wing demonstrators protesting against colonial control.14 This level of grass-roots activism fed into the Liberal Party led by Mohammad Mosadegh, who became Iran’s Prime Minister in the early-1950s, as well as the hugely influential Tudeh Party (‘Tudeh’ in Farsi means ‘masses’, indicating in effect it was Iran’s Communist Party).

The 1950s was also the critical period in Iran when the USA began to muscle its way into Iran, displacing British colonial domination. This carefully orchestrated change in patterns of influence is well documented in memoirs from the time. As one example, Farmanfarmanian observed: ‘Jerry Dooher, first deputy of American Embassy in Iran and an influential political figure, was well known for his strong views against the unjust policies of Britain in the British-owned Anglo Iranian Oil Company (AIOC)’. He continued:

One afternoon, Dooher told me: “You should throw out the British oil company”. Every time I saw him he would repeat this and would say: “Create new conditions, what is wrong with that? Whatever happens, we, the Americans, would send our ships and would buy your oil”.15

George McGhee, the US Assistant Foreign Minister who also happened to be married to the daughter of Everette De Golyer, a Texas oil millionaire, travelled to Abadan specially to create ‘fairer’ conditions for negotiations with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.16 McGhee was a partner in De Golyer’s oil prospecting company and as such had already discovered ‘a sizeable oil field in Louisiana’.17 Blatant financial self-interest was evidently the name of the game.

Iran’s initial share of the profit from the oil industry, back in 1910, had been only 15 per cent; this was later increased to 20 per cent, just prior to nationalisation, as an attempt by the British powers to win a longer lease for its extraction. In that period prior to nationalisation, Britain owned over 51 per cent of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and exercised total control over the company and its employees. However, following a US-backed coup d’état in Iran in 1953, the Iranian share went up to 25 per cent and the controlling ownership of Iran’s oil consortium was now to be divided between America, Britain, and France/Netherlands. However, the USA’s newly acquired role as chief arbitrator meant that relations between Iran and Britain had been irrevocably changed. During the 1950s America was intent on replacing Britain as the major colonial power in the Middle East, as part of its wider plan for global domination in the Cold War era. Mary Ann Heiss has written of this geopolitical battle for control over Iran’s oil resources:

… the shifting Anglo-American relationship regarding the Iranian oil nationalization crisis of the 1950s [had three phases] … the era of US benevolent neutrality; the era of Anglo-American partnership; and the era of US domination.18

This neo-imperial activity by America in Iran and the Middle East had of course begun before the Second World War; what was different now, however, was its intensity.19 The United States played a clever double-edged game in Iran. On one hand, via state officials like Dooher and McGhee, it encouraged Iran to regard British policy towards Iranian oil as wrong and unfair. On the other hand, when it came to critical moments such as in 1951 when Britain was imposing sanctions against Iran in wake of oil nationalization, they helped the British by spying on Mosadegh’s government. Indeed, it appear to have been the Americans who planned the 1953 military coup, using the CIA’s might, with aid from MI6, thereby bringing down the democratically elected prime minister just because he had nationalized the oil reserves.20

THOUGHTS ON REBUILDING ABADAN

Abadan’s fertile location and its role as a major river port might suggest more than enough reasons for investors to be interested in the city, but this clearly isn’t the case. The current Mayor’s slogan – ‘Think global, act local’ – is a catchphrase that has of course been used often before, but one that needs to be unpacked and readjusted to suit the local conditions. The municipality has, as part of its latest planning policy, designated the northern riverfront in Abadan as a ‘family park’ for recreational activities, motorcycling, horse riding, etc. It is even being named Jazeereh Shademani, which translates as ‘Fun Island’, with the hope is that other potential sites for urban regeneration will be incorporated into the city’s plan as a result.

11.8 Current state of Arvand River on the edge of Abadan

11.9 Sikh temple presents an appropriate alternative climatic model

To the south, overlooking the date palm forest, is the Arvand River with its potential as a locus for the customary evening promenade of family groups, a veritable social parade similar to that in Italian cities. However, the dusty southern wind from the desert creates a real environmental hazard. It is a problem exacerbated by the continual loss of agricultural land in Iraq and by the refusal of the Saudi Arabian government, ever since the Islamic Republic came to power in Iran, to deal with its own (non-farming) desert areas to reduce the effects of ecological damage through prevailing winds. Iran today doesn’t have the same international backing as the Pahlavi dynasty once did to pressurise Saudi Arabia into mitigating this eco-environmental pollution. Instead, layers of southerly desert dust regularly cover much of Abadan as well as other Iranian cities along the Persian Gulf coast.

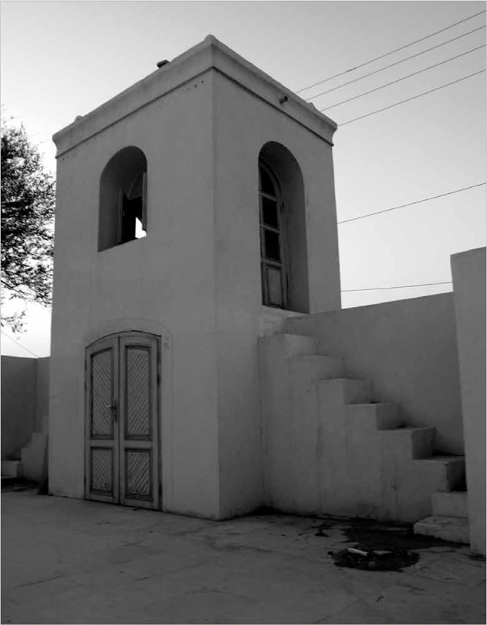

However, if one continues along this southern edge of the city, there is an important old Sikh Temple which presents a far more appropriate model of how to respond to the climate. It contains a peaceful courtyard with an optimal ratio of courtyard size to height of surrounding walls. In this manner, the width provides adequate protection from the dust and noise from the street while also forming a shaded courtyard. The building’s entrance is articulated by a small and delicate ‘watch tower’ that responds to the city scale. The back of the temple’s courtyard faces onto the river and palm trees, with a high wall protecting its interior from dusty desert winds. It’s a sensible, passively controlled arrangement which ought to have been used more in the design of hotels and other new buildings in this region. Likewise, a wide platform hovering over the bank of the Arvand River in front of the lively fish market seems an ideal spot for evening promenading. As a port city, and certainly in the milder temperatures of the non-summer period, it could support a few seafood restaurants or stalls selling dates, pizza and other produce, so as to create a public focus for different age groups. And yet this potential collective space, shaped by local climatic conditions and memories of the old port district, remains a forgotten marginal site.

11.10 Sikh temple courtyard

Maybe the Mayor’s new slogan might actually mean something if he were actually to initiate some relevant economic and environmental strategies. Decent public spaces, custom-made to suit Abadan’s culture and climate, could be the basis for socio-economic regeneration. Urban strategy needs to help local traders and different communities use the city in an inclusive and environmentally comfortable manner, while also respecting the habits and tastes of different age groups, and of both genders. In Iran today, this is a critical issue, given that the forces of global capitalism have not as yet totally dominated and changed people’s lifestyles. Instead, the economic sanctions imposed on Iran by the United States (and some European countries) for the last two decades have forced the country to develop its own industrial base – including oil refining, car manufacturing and building materials, amongst others. It also compels Iran to find alternative passive climatic techniques to reduce energy use. Hence the sanctions have resulted in a return, in some trades at least, to older practices of recycling materials and goods, helping local economies to survive. In most local markets in Iran you will find places to repair every household object. This recycling of objects happens due to economic restrictions, not for environmental reasons. However, this level of self-sufficiency has equally slowed down the pace of entry of global forces; local craft industry is very much still alive (even if to some extent affected by the use of imported machinery). In terms of building materials, for instance, the result is a cultural collage ranging from local Iranian elements to a mixture of Turkish or Chinese products. It makes it hard to assess accurately the relative quality of locally made materials, yet it’s also critical that the Islamic Republic government supports Iranian-made products to bolster costumer confidence.

IDENTITY SHIFT FROM GLOBAL TO URBAN SCALE

Despite the obvious cultural and climatic characteristics of Abadan and Khorramshahr, confusion remains about their current and future identities, and how these should be reflected in terms of urban grain and building typologies. Prodigious wealth from oil and gas in the Pahlavi era could easily have brought about intelligent city planning and social reform, reducing the gap between classes, as well as providing decent infrastructure. But this simply didn’t happen. Instead there was an imposition of neo-colonial architecture from Europe, growing socioeconomic friction, and the almost total destruction of the city fabric in Abadan and Khorramshahr. Similarly, very little of the massive surge in income following the ‘Oil Crisis’ of 1973–1974 was used for creating economic self-sufficiency or industrial training in the Shah’s Iran.

11.11 Private facilities for European engineers, managers and their families in Abadan

11.12 Small one-bedroom houses built by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company for local workers

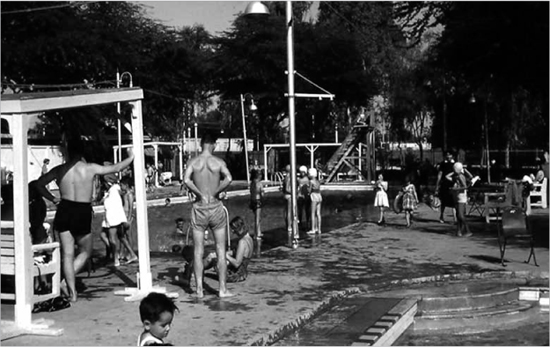

Indeed, the excessive reliance on oil revenue during the Pahlavi dynasty, and then to a lesser degree by the Islamic Republic government, has caused Abadan to become divided by extreme wealth and poverty. During the 1960s and 1970s, the surface image of the city changed. But this new ‘European look’ – with its private bars, nightclubs, discos, cinemas, expensive hotels, casinos, fast cars in wide roads, outdoor swimming pools and western-style villas – was only aimed at elite groups who came from Tehran or abroad. Locals weren’t allowed to use these facilities even if they dressed up specially to do so; rather, the new pleasures were for ‘members only’.21 Houses copied from Europe, set within town planning copied from North America, formed residential enclaves for high-ranking managers and engineers in the oil business. Some of these dwellings even had 10–12 bedrooms, whereas lower-ranking technicians and manual workers, especially Iranians, were squeezed into 1–2 bedroom apartments. As in other Persian Gulf cities like Dubai, Manama or Kuwait City, the expatriate managers and engineers were only temporary residents. Most of the new villas were carefully located in the west of Abadan, where the air is cleaner, while workers’ apartments were in the dustier and more polluted areas to the south or east. Local workers also had to live continuously in Abadan, whereas the elite groups, being unable to deal with the hot climate, would spend several weeks a year in northern Iran, or abroad, leaving much of the city unoccupied. Today, the larger neo-colonial houses tend either to have been divided into smaller apartments or, as mentioned, are left unoccupied (see Plates 17 and 18).

ABADAN OF THE 1930s AND 1940s: A FAST-MOVING TRANSIENT CITY

In 2009, Abadan and Khorramshahr celebrated the centenary of the discovery of oil in Iran, something which was to have such a great impact on all levels of life. Abadan’s population spurt had led to a dramatic expansion of the city by the 1950s, with its urban planning led by British and continental European experts influenced by the Garden City movement or the siedlungs that had appeared in cities like Berlin, Frankfurt or Stuttgart in the 1920s. It is thought that a British architect, James M. Wilson, was the mastermind behind the layout and house designs for the Bawarda neighbourhood in Abadan. These mini-cities, known in Iran as shahraks, however missed out many elements of the Garden Cities or siedlungs, such as social housing, health clinics and nurseries.22

The German siedlungs were indeed designed for lower-income families, whereas ironically in Abadan the new settlements were intended for the minority upper classes and European expatriates. As highlighted in Murray Fraser’s book, Architecture and the ‘Special Relationship’, the earlier social goals of the British Garden City movement came gradually to be dropped in the post-war period in favour of incorporating Americanising trends such as increased car use.23 In Abadan, as in present-day Dubai, this use of American-style patterns of suburbanisation led to a similar outcome. Indeed, in Iran, the concept of hybrid Anglo-American town planning was clearly intended to segregate social classes by dividing locals from a wealthier transient community.24 It was fed by the growing influence of American ideology in the Persian Gulf region, and in most aspect of peoples’ daily lives, during the Cold War. Given that the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company was the largest employer in all of Iran, Abadan’s layout was pushed in unsustainable directions. The result was wider boulevards, large American cars, gated communities, casinos, bars and off-licences located strategically in main squares, private open-air swimming pools, tennis courts, Pepsi Cola and cigarette adverts, and countless other symbols of Americanisation. In this manner, US-style planning imposed the same canonical pattern onto many Middle Eastern cities.25 As one local citizen recalls:

Abadan was like a European city with American Chevrolets, so it resembled a strange mixture. It was like us watching an American movie filmed in American suburbs but the houses looked European. It was confusing but we liked it, yet it was also unreal because of the type of people who were driving the cars. They never walked on the pavements or in the streets. We only had a glimpse of them from a distance, behind their fenced mansions. They represented a maximum of 10–15% of the population, but it was funny to watch them.26

As demonstrated by Fraser, this strange cultural hybrid of Anglo-American town planning wasn’t unique to Iran, even if did take on notably different forms in other countries such as Britain.27

The consequences for Abadan and Khorramshahr were drastic. Cities within cities were created with deep hedges around ‘mansions’ in exclusive neighbourhoods to protect the elite from poorer locals. Rather than the passive environmental strategies that dwellings had used traditionally, sensible practices were given up in favour of polished stone, reflective surfaces and centrally located entrances just to create a grand image, but one which needed to rely on heavy energy usage to keep occupants cool.28 Sadly, little has changed since the collapse of the Pahlavi dynasty, and so these gated shahraks continue to fragment the different neighbourhoods of Abadan and Khorramshahr.

ZOOMING IN

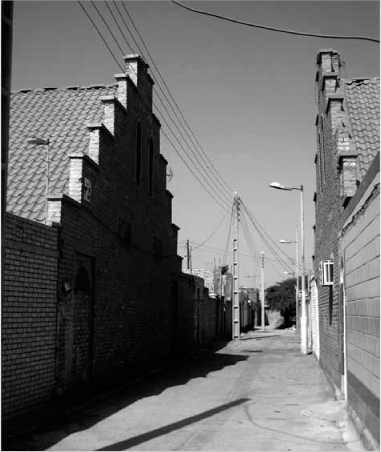

The urban planning that was applied to Abadan and Khorramshahr in the 1950s and 1960s was manifestly wrong. These American-style boulevards and gated neighbourhoods, with almost no provision for shading or transitional zones between structures, create individual disconnected buildings reliant on expensive air-conditioning and other mechanical systems to allow people to use them. It’s total madness, and yet Abadan’s local authority, just like every other Iranian municipality, is still busy spending a large portion of its annual budget on road widening rather than serious environmental improvements. If a city with an average summer temperature of 40–50°C is to function effectively, close consideration needs to be given to the scale and proportion of streets, alleyways, external shading, public open spaces, transitional zones, etc.

During the summer siesta hours in Abadan and Khorramshahr, which stretch from 12.00 noon to 6.30pm or 7.00pm, one has no choice but to go to sleep. Outside, one cannot find a taxi. Children are unable to use playgrounds as it is too hot. Office workers therefore tend to work from 7.00 am to lunchtime and then start again in the early evening. Hence cities in this region stop and sleep in sensible ways, according to environmental logic. Practicing the siesta in a hot climate conserves energy and reduces the need for air conditioning in the hottest periods, and the energy that people gain from their midday meal is then released for the ‘re-launch’ of the city in the cooler evening period. It is no accident that, for instance, the local municipalities in Abadan and Khorramshahr provide rooms for employees to take an afternoon snooze.

Poor environmental planning in these two cities has also greatly reduced the amount of external spaces usable in summer. This is problematic, since more time is thus spent indoors in poorly constructed homes, offices and shops, which in turn increase the demand for air-conditioning. A lack of awareness in how to respond to climatic context is not new; instead, what is different is the denial by municipalities about the importance of the issue. They simply refuse to learn from the fabric of the old city with its courtyards and roof-top terraces, some of which are still in operation in Abadan and Khorramshahr. However, perhaps one of the problems is that so little of pre-oil Abadan remains. Instead, one could look at other cities on the northern coast of the Persian Gulf, such as the fishing port of Bandar-e-Deylam – which lies about 150km east of Abadan – to see how street lifestyles and everyday cultural habits can positively influence buildings and urban form. Traditional cities in the Gulf region generally had one main commercial street which contained the bakeries, butchers, teahouses, offices, etc., and also a narrower residential street, off from which were narrow alleyways feeding into a series of courtyard houses. These dwellings had terraces with overhangs, shading devices in front of windows, trees and other kinds of shading devices. The hierarchy of movement from the external public space to the internal private space thus had an environmental as well as a cultural logic, in that the built form reduced the amount of heat gain while also channelling winds in order to cool dwellings. When mapping the movement of children, housewives and old people in such cities, one finds that, for instance, children instinctively play in the cooler narrow alleyways next to where the older citizens locate their seats, and can supervise them. These environmentally efficient urban pockets cannot possibly be achieved by using the wide roads and dispersed suburban dwellings which tend to be favoured today.29 In other words, there are basic principles for organising urban spaces and building clusters in hot climates which simply cannot be ignored.30

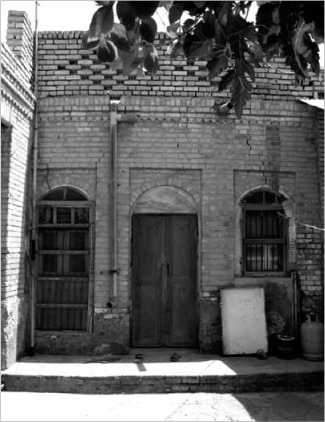

11.13 Walled garden courtyard house in Abadan with articulated brickwork and plants for shading

In traditional houses in Abadan and Khorramshahr, the position of courtyards were also carefully related to prevailing sea breezes. North-facing facades had larger non-shaded openings, whereas southern facades had smaller windows with porches and shutters to offer inexpensive passive cooling. Courtyard entrances were located in the direction of the westerly or south-westerly wind, which also dictated the position of doors into rooms. Doors were always positioned to catch as much wind as possible, and cooling was intensified by hanging a thin curtain over the opening which was constantly sprayed with water. A typical courtyard contained trees and plants for cooling as well as a shallow pond, and rooms were raised above ground level. Small bread-making kilns were frequently positioned within the courtyards.31 In hot climates it made environmental sense to have domestic kilns in the correct place so they can then as a heat exchange system when the weather becomes cooler. These devices, which can also be regarded as strategic features at the urban level, provided the kinds of invisible passive technologies which worked so well to improve the bodily comfort of citizens at a 1:1 scale.

RETURNING TO SOME SIMPLE CLIMATIC DESIGN MOVES

In the context of the 1950s, when environmental awareness and sensitivity to cultural identity weren’t seen as such priorities, it is perhaps not surprising that the urbanism introduced by British and American planners was so contrary to the specificity of Abadan. However, today, local bodies such as Abadan Municipality or the Cultural Heritage Office ought to propose more intelligent alterations to historic buildings and urban spaces. Instead, one finds that their designs over the last decade are totally inappropriate: for example, in public parks they just select standard play equipment out of European catalogues and then import it from Dubai! Street furniture and the sorts of materials being used for building envelopes reflect a similar lack of local cultural and environmental awareness.

Clearly, a better way is required to deal with a city like Abadan. This however raises the question of what else than car-based ‘gated villages’ or the surreal flues of oil and petrochemical plants could be used to characterise Abadan? I would suggest a few other currently undervalued elements of cultural identity:

1. Districts containing fine 1930s Art Deco buildings;

2. The two majestic rivers encircling the city;

3. Two historical cinemas, the Naft and Rex, each symbolic of its political period;

4. Summer roof-top living building features designed by local architects;

5. Typical bakeries, whether in domestic courtyards or outdoors in streets;

6. Traditional brickwork buildings with their careful detailing

7. System of drainage trenches, usually openly exposed.

It is therefore still possible to find individual buildings in neighbourhoods which possess fine detailing similar to that found in Isfahan and Tehran in the 1940s and 1950s. Clearly there were some skilled local bricklayers able to combine intricate tiling with exquisite brick details, creating an important piece of Abadan’s cultural heritage. Likewise, the modifications introduced by some Iranian architects and engineers for the ‘1000 Homes’ project, as erected by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company for local workers in the 1960s, offers a telling example of cultural and environmental identity. Adapting some inadequate designs by the British architect, James M. Wilson, these Iranian architects and engineers altered the housing forms and plans to incorporate roof-top living to take advantage of cooler air in the evening and at night.

11.14 Brickwork and glazed tiles in the hybrid dwellings of the Bawarda Garden Suburb, as reminiscent of central and southern Iran from the 1930s to the 1950s

Indeed, this powerful older residue in Abadan could be tapped into by looking at other aspects of its built fabric. Most houses in the region were once made of local Marjani stone, which is sadly no longer used for new developments. As noted, these traditional dwellings tended to be raised up by 2–3 metres above the ground to catch all the available sea winds. In addition, it protected the houses from rising damp or flooding from seawater, while also marking out the public/private threshold between the courtyard and the house. Rooms within houses, and windows within rooms, were also carefully situated. Sleeping areas/bedrooms were positioned in the direction of cross ventilation from the entrance and across the courtyard. The kitchen, as a source of heat, was placed away from the sitting room and at 90 degrees to it. And best of all, the sitting room was located on the outer wing of the courtyard with its doors and windows be openable onto the latter, facing north rather than south, to reduce heat gain and provide the best conditions for cross-ventilation. Predictably, most of the new buildings in Abadan and Khorramshahr now ignore these practical, invisible technologies, resulting in the loss of air movement and light quality; similarly, their foundations and column plinths are gradually being damaged and eroded because of rising damp and the high salt content in the water. We have forgotten so much that we once knew.

11.15 View of the ‘1,000 Homes’ project by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company for Iranian oil workers in Abadan, as modified by Iranian architects from original designs by the British architect, James M. Wilson

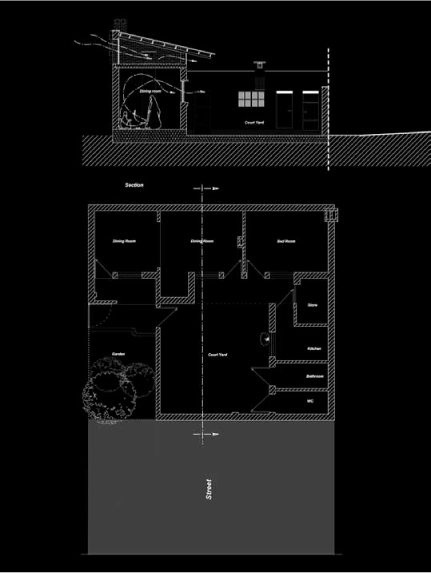

11.16 Plan and cross-section of a dwelling in the ‘1,000 Homes’ project showing ventilation strategies

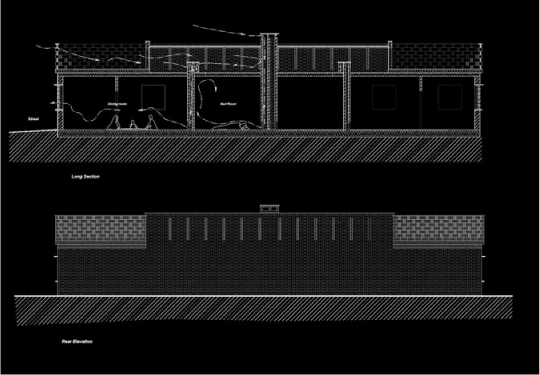

11.17 Elevation and longitudinal section of paired dwellings in the ‘1,000 Homes’ project showing ventilation strategies

CONCLUSION

My visit to the cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr to carry out research for this chapter involved peeling off a number of invisible layers. What was illuminated was a range of active or inactive global and local forces, many deeply concealed, within this culturally and economically important – yet deeply neglected – region of Iran. In the province of Khuzestan, and in Abadan in particular, there is a close link between the socio-political landscape and people’s cultural and environmental needs; likewise, these factors were traditionally manifested in the spatial organisation of cities and individual buildings. In this sense, my study of Abadan and Khorramshahr demonstrates the crucial interweaving between climatic conditions and cultural practices.

The problem, however, is that contemporary urban planning and methods of building design create a damaging tendency towards over-consumption and wastage. ‘Modern’ technologies such as air-conditioning are difficult to control and largely ineffective in terms of creating a cool, stable and healthy environment in such a hot region. This over-reliance on air-conditioned houses, cars and working spaces has led to building types (and indeed cities) becoming too similar across Iran, whether they are in the dusty desert heat of Khuzestan, or in the dry cold of Tehran, or the even colder rainy north of the country. Low-quality building envelopes and the forgetting of traditional passive environmental techniques are thus squandering of energy resources and are resulting in the loss of specific physical and spatial identities that buildings and cities once had in different Iranian provinces.

It is vital therefore to record and analyse the older building and spatial practices. If one looks properly in Abadan and Khorramshahr, one can still find many of these ‘invisible’ techniques; even more importantly, see how they interact with everyday habits and cultural practices. These are small, yet critical, acts which can make living conditions in buildings and cities far more comfortable, affordable and sustainable. Hence the reintroduction to Abadan and Khorramshahr of appropriate street furniture, proper provision of shading and planting, and a smarter urban strategy for open public spaces could encourage the better use of these cities even in the summer period of ultra-high temperatures.

Instead, what we find is that the beautifully shaded and planted courtyards and gardens of traditional Iran, with their cool ponds, are being replaced by unbearably hot and non-shaded spatial models taken from western car-based suburbs. Indeed, the notion of open-air car parks in the baking heat of cities of this kind simply makes no sense. In today’s urban planning in Iran, whether for a city in the north or the south, there is now the same standard width used for roads, the same lack of hierarchy from public to private spaces, and the same problems of shortage of shade or transitional zones between blocks. Similarly, at the building scale, thin outer walls with no insulation have in high-rise apartment blocks supplanted the thick earth walls that older houses once had, and so the new dwellings gain and lose heat far too quickly. Metal doors/windows are being used instead of wooden doors/windows, again accentuating problems of excessive heat gain and heat loss. All this is being done for short-term profit by the minority who control building development in cities like Abadan and Khorramshahr. New technology based on cheap source of heating and cooling is thus producing a lazy approach to city planning. But what happens if and when citizens find themselves unable to afford their fuel bills? In such a case, what are they possibly do during the blazing heat of summer or bitter cold of winter?

This is why a clear and suitable urban strategy is urgently required for Abadan and Khorramshahr. Bold infrastructure projects could well include the following: an extension line for the north-south railway that currently ends in Khorramshahr; improved waterways and more intensive use of river banks; the redistribution of essential services to all neighbourhoods; and the reopening of some of the great private schools built under British rule (such as Mehragan School) or in the Pahlavi era, albeit this time making them available to ordinary families rather than just the elites of those earlier periods. Above all, traditional everyday practices and passive building techniques – invisible, but extremely effective and sustainable – have to be reinforced. In my discussions with local citizens and municipal officials in Abadan and Khorramshahr, the importance of better public policies to cut the culture of waste was raised again and again. At the moment, it might seem to some to be a far-off issue, almost a luxury, because of the availability of cheap fuel in Iran. Yet soon enough it will become a matter of survival, especially for the less well-off. Once western sanctions end and Iran opens up once more to the global economy, with its higher inflation levels, then the situation will rapidly become untenable.

Despite the obvious warning signals, the current Islamic Republic government seems less and less interested in developing alternative means to ensure sustainable economic growth. Unlike in 2000, when the Iranian Fuel Conservation Organization (IFCO) was set up by the Ministry of Power and Energy to reduce oil and gas usage by energy-saving measures in building construction, today there is little evidence of any such strategies in the province of Khuzestan.32 Hence it is now time to act in Abadan and Khorramshahr since there are still traces of low-technology building practices which can cut energy use and create a sustainable environment which is culturally determined. The different levels of Iranian government, whether nationally or locally, need to concentrate on supporting these alternative ‘invisible’ ways of addressing climatic needs. The present emphasis on developing nuclear energy as the back-up plan might seem on the surface to be a good option for a developing country like Iran, given the global context, but of course opponents like the United States and Israel see this as just a smokescreen for producing Iranian nuclear weapons. Far less controversial and more logical would be to finance research to improve building practices and energy efficiency; in Iran, as elsewhere, energy consumption in buildings makes up around half of all demand.

11.18 Beautifully crafted modern tower in the Miras Farhangi building in Abadan

If a more enlightened policy was adopted by the Iranian government, then plenty of sources of inspiration could be found. As mentioned above, Abadan and Khorramshahr have histories which are as vital to the emergence of modern Iran as, say, Isfahan, Shiraz or Yazd. While these other cities might be more famous and beautiful, even Abadan and Khorramshahr can be seen to possess valuable architectural and urban assets. Therefore these two major cities of Khuzestan need to celebrate their natural resources other than just plentiful oil and gas deposits. They also possess fantastic varieties of palms, dates, fish, poetry, music and such like; they have a climate which can be used positively, especially during the balmy seasons of spring and autumn; plus they have powerful links to the rivers, sea, sand and desert. In terms of human habitation, both contain fascinating traditions of courtyards, alleyways, roof-top terraces and a host of invisible, ordinary spaces. These older urban traditions need to be reconnected to people’s lifestyles and cultural practices in Abadan and Khorramshahr. As Iain Borden writes so evocatively about the relationship between architecture and the everyday:

We must recognize that, beyond the square, piazza and avenue, cities need hidden spaces and brutally exposed spaces, rough spaces and smooth spaces, loud spaces and silent spaces, exciting spaces and calm spaces. Cities need spaces in which people remember, think, experience, contest, struggle, appropriate, get scared, fall in love, make things, lose things and generally become themselves.33

NOTES

1 ‘During the 1970s, the agrarian reforms of the White Revolution … skyrocketing oil revenues, and Iran’s new role as the US’s Persian Gulf gendarme combined to bring rapid – and destabilizing – social, political, and economic change. Oil income shot up from $22.5 million in 1954 to over $19 billion in 1975–1976. By mid-decade, nearly half of Iran’s people lived in urban areas (up from 30 percent a decade earlier).’ Quote from Larry Everest, ‘The US & Iran: A History of Imperialist Domination, Intrigue and Intervention’, Revolution, no. 89 (20 May 2007).

2 Hamid Naficy, in Rosa Issa & Sheila Whitaker (eds), Life and Art: The New Iranian Cinema (London: National Film Theatre, 1999), p. 15.

3 Ibid. Ironically, similar imagery and products (Coca Cola, hamburgers, etc.) were also used in the film Goodbye Lenin (2003) by Wolfgang Becker to show the arrival of global capitalism in East Germany after the fall of the ‘socialist’ planned economy of the Eastern Bloc.

4 Sirus Tahbaz, The Life and Arts of Forugh Farrokhzad: Lonely Woman (Tehran: Zariab, 1998), p. 189.

5 Habib Ladjevardi, Labour Unions and Autocracy in Iran (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1985), pp. 173, 328.

6 In 1976, in the last years of the Pahlavi dynasty, Amnesty International reported that Iran had the ‘highest rate of death penalties in the world, no valid system of civilian courts and a history of torture which is beyond belief. No country in the world has a worse record in human rights than Iran’.

7 A.K. Lyravi, The History of the City of Deylam (Bushehr: Sharo Publishers, 2001), p. 69.

8 ‘Only a low 9% of managers (of the oil company) were from Khuzestan. The proportion of natives of Tehran, the Caspian, Azerbaijan and Kurdistan rose from 4% of blue collar workers to 22% of white collar workers to 45% of managers. Thus while Arabic speakers were concentrated on the lower rungs of the work force, managers tended to be brought in from some distance.’ Quote from ‘Abadan’, Absolute Astronomy website, http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Abadan (accessed 14 September 2010).

9 ‘The United States, Sweden, Belgium, the Netherlands, Pakistan, and Germany all refused to make their technicians available to the nationalized Iranian industry.’ Quote from ‘Abadan Crisis’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abadan_Crisis#cite_note-4 (accessed 14 September 2010).

10 Interview by the author with Mr Anfi, owner of the photographic shop in Ferdosi Street, Abadan, Iran, 18 July 2009.

11 The Castle (1926) is a novel by Franz Kafka. ‘In it a protagonist, known only as K., struggles to gain access to the mysterious authorities of a castle that govern the village where he wants to work as a land surveyor. Dark and at times surreal, The Castle is about alienation, bureaucracy, and the seemingly endless frustrations of man’s attempts to stand against the system.’ Quote from ‘The Castle’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Castle_(novel) (accessed 25 May 2010).

12 Mike Davis & Daniel B. Monk, Evil Paradises: Dream Worlds of Neoliberalism (New York: New Press, 2007), pp. 35–36.

13 Ibid., p. 39.

14 ‘The Oil Workers Union was attacked and banned during Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1930s. By 1946 the unions were still banned under the new Shah. The economic gap between British workers and the local Abadani workers was extensive. The British were not complying with any of their contractual agreements to provide schools, hospitals, services, roads and reasonable above-poverty wages for the local workers. This led to series of strikes by workers in March 1946 by the Oil Workers Union. The British formed a counter union (paying Arab workers in the Oil Company to join it). The plan was to axe Khuzestan province from rest of Iran. Following the massacre of the workers, in which 50 were killed and 170 were injured, the British Navy was on stand-by in Basra and stopped work in the Oil Company.’ Quote from Manucher Farmanfarmaian & Roxane Farmanfarmaian, Blood and Oil: Memoirs of a Persian Prince (New York: Random House, 1997), p. 217.

15 Ibid., p. 287.

16 Ibid.

17 Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power (London: Simon & Schuster, 1993), p. 452.

18 Essay by Mary Ann Heiss, Department of History, Kent State University website, http://128.36.236.77/workpaper/pdfs/MESV3-6.pdf (accessed 20 August 2010).

19 ‘Chapter 3: Foreign Policy and Antitrust: The Cartel Case and the Iranian Consortium’, taken from Multinational Oil Corporations and US Foreign Policy Report – together with individual views, to the Committee on Foreign Relations, US Senate, by the Subcommittee on Multinational Relations. See: Mount Holyoke University website, http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/oil1.htm (accessed 20 August 2010).

20 Yergin, The Prize, p. 470.

21 During my many taxi journeys and discussions with local people in Abadan and Khorramshahr during the course of this research, many stories were painted about the realities of the city. As one taxi driver, Mahmood Rejaei, told me: ‘We were able to see the private pools from our roofs and dreamed about swimming in them, but those who died have taken the dreams with them. The clubs were the same. Even if we were able to borrow some nice and clean clothes to go, they would have recognised us and so we were never able to smuggle our way in to them.’

22 Ronald V. Wiedenhoeft, Berlin’s Housing Revolution: German Reform in the 1920s, Architecture and Urban Design no. 16 (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Research Press, 1986), p. 10.

23 Murray Fraser (with Joe Kerr), Architecture and the ‘Special Relationship’: The American Influence on Post-war British Architecture (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), pp. 135–145.

24 ‘Planning was utilized to build the segregated city, in which a European, upper-class quarter was separated from the rest of the city. French Morocco offers the most vivid example of this kind of city planning: European quarters were built separate from the old medinas; important urban cultural sites were preserved; and the European part of the city utilized the most up-to-date urban-planning techniques. Similar practices were followed in Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.’ Quote from ‘Urban Planning, The Colonial Period 1800–1945’, Gale Encyclopedia of the Middle East and North Africa, ‘Reference Answers website, http://www.answers.com/topic/city-planning (accessed 20 August 2010).

25 ‘US and British oil companies also established company towns for their workers. The Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO), for example, used Western planners and engineers to lay out company towns such as Dhahran and Abqaiq using a system of blocks with a grid pattern. Similarly in Iran, British planners modeled the city of Abadan on the landscape of suburban England. Middle Eastern countries depended on the West for qualified planners and consultants to carry out urban planning. Consequently, a planning technique then common in the West, the master plan, was imported to the Middle East and soon became ubiquitous throughout the region. Most plans were end-state master plans, in that the ultimate look of the city in the future was already predetermined. Most plans were also unclear about the process of city planning or procedures for implementation. Additionally, the plans were usually static and design-oriented, with little consideration for the social and economic needs of the majority.’ Quote from Hooshang Amirahmadi, ‘Regional Planning in Iran: A Survey of Problems and Policies’, The Journal of Developing Areas, vol. 20, no. 4 (1987): 501–530.

26 Interview by the author with Mr Anfi, owner of the photographic shop in Ferdosi Street, Abadan, Iran, 18 July 2009.

27 Fraser, Architecture and the ‘Special Relationship’, p. 135.

28 Solar radiation on horizontal surfaces being of course at their maximum during summer where there is a use of over-reflective building materials. See: Richard Nicholls, Low Energy Design (Oldham: Interface, 2002), p. 131.

29 Mike Jenks & Rod Burgess, Compact Cities: Sustainable and Urban Forms for Developing Countries (London: Spon Press, 2000), p. 343.

30 Compact city design principles and the argument for grouping of buildings to reduce heat loss and in the case of Abadan heat gain in individual buildings. See: Nicholls, Low Energy Design, p. 49.

31 The traditional earth stove located in the corner of the courtyard gardens or sometimes under the ground is still a very common practice in Iran and some other Middle Eastern countries.

32 ‘Iranian Fuel Conservation Company (IFCO), a subsidiary of National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), was established in 2000 with the mission to regiment the fuel consumption in different sectors through review and survey of the current trend of consumption and executing conservation measures nationwide.’ Quote from ‘About Us’, Iranian Fuel Conservation Company website, http://www.ifco.ir/english/index.asp (accessed 27 August 2010).

33 Iain Borden, ‘The unknown city of architecture and the everyday’, Re-public website, http://www.re-public.gr/en/?p=40 (accessed 27 August 2010).