Abu Dhabi, UAE

The land where the United Arab Emirates lies today is in a geographical location which contributes to its high temperatures, its challenging desert climate, as well as its inhospitable and desolate terrain. At the same time, the very same location provides for abundant petroleum and natural gas reservoirs which have been blessing the country – and more specifically, in relation to the UAE’s capital city of Abu Dhabi, with the means to provide for a better future for its people and future generations. A society burdened by such a harsh climate and sterile land developed sophisticated survival skills through ephemeral architecture and its connection to the water. The nomadic nature of the Bedouins, and the need to deal with the extreme heat and high humidity levels, informed a specific quality of shelter, one that needs to deal with controlling the micro-climate while serving the community’s needs. ‘In less than one lifetime, the Gulf has transformed from one of the most disengaged parts of the world to a strategic fracture point of globalization in a regional context.’1

7.1 Map of Abu Dhabi in context of the Persian Gulf

Abu Dhabi is becoming a fascinating amalgam of thresholds. Successive tensions between its historic, economic, political, cultural, social and technological thresholds in the last 50 years have created the ever-evolving experience of the contemporary Abu Dhabi. This evolution was carefully shaped by inspired political leadership who channeled large sums of investment into culture and building infrastructure, while also embracing globalization as a means to modify cultural traditions in a non-threatening way, and sharing the newly found wealth with the native society.

Informal coastal settlements and traditional Gulf architecture, composed of vernacular use of temporary available materials, were unable to provide for the new demands of a modernizing city – and currently a globalizing city. A fascination for progress and development in such a barren land is not only understandable, but also predictable. This dramatic shift affected Abu Dhabi’s urban design and architecture in many ways. This is clearly represented in the introduction of a rigid street grid with oversized boulevards and superblocks and the imported Modernist approach to urban development which demanded building designs that carried ‘Brutalist’ characteristics, expressed as modest-sized concrete blocks. The 1980s and 1990s brought Islamic ornamentation to the concrete boxes as well as into the more recent glass curtain facades. The first decade of the 21st century embraced gargantuan architectural and urban scale in Abu Dhabi, introducing the currently accepted ‘hyper-modernism’ direction into built form in the city.

This chapter investigates the particularities and ways in which these dynamic inter-relationships, which can be seen as urban ‘thresholds’, have impacted upon Abu Dhabi’s physical evolution. Particular interest will be shown in discovering how forces of globalism influenced changes in the traditional delineation of social space, the private versus the public, and the introduction of pseudo-traditional Islamic principles in urban design and architecture.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The bleakness of the land compelled local Bedouin tribesmen to explore the sea and its resources. Western descriptions both from the early- and late-20th century evoked the natural setting in which settlers had to deal with in the region. One wrote: ‘The coast of the Arabian [Persian] Gulf presents remarkable peculiarity in possessing from one end to the other a series of creeks, lagoons and backwaters without which its barren and desolate terrain would barely have been habitable.’2 Abu Dhabi Island served essentially as an ephemeral site for shelter, supporting the fishing and pearl-diving activities performed by nomadic people travelling from the mainland: ‘For centuries they had to fight against the privations of a land that barely provided the means of subsistence, and their lives revolved around the presence or absence of water.’3 Then, according to Bedouin tradition, one tribe’s leader happened to find a fresh-water spring after crossing over to the island to hunt a particular gazelle. It seems that the gazelle stood on the very spring of fresh water which was to become the basis of the settlement. This availability of water attracted other nomadic people, and it is believed that the first proper settlement of Abu Dhabi dates back to 1761; at that point, it consisted of 20 barasti huts built of palm fronds on timber frames. Sheikh Dhiyab bin Isa led his people from their home in Liwa to this area, which became known as Abu Dhabi, meaning ‘father of gazelle’.4

Historical evidence about the early settlement of Abu Dhabi Island was most likely kept alive by oral traditions and legends among the local population. As is described by the Centre for Documentation and Research, Sheikh Dhiyab founded the coastal settlement but he himself remained in the area between the island and the inland oases of Liwa and Buraimi, leading the Al Bu Falah section of the Beni Yas tribe.5 According to Trench, the earliest inhabitants of the Abu Dhabi settlement relied almost entirely on fishing and pearl diving as there were no traces of ordinary crop cultivation and very few date palms. He also suggests that even after the arrival of foreign presence due to European colonial intervention in the Gulf region, development was uncommon: ‘… the anchorage for large vessels is totally unsheltered and lies more than two miles from the shore.’6

The need for each Bedouin tribe to control and cater for its own water supply and livestock perpetuated the erection of watchtowers and forts: ‘It is presumed that the round tower [Qasr al Hosn] which still exists today, is probably the remnant of the earliest-known structure built by the Al Bu Falah Sheikh during the first settlement of Abu Dhabi.’7 Within a couple of years after being founded, the settlement of Abu Dhabi had expanded to 400 barastis, and its population continued to increase thereafter. The watchtower of Qasr al Hosn was most likely erected at the end of the 18th century, this also being period in which the Beni Yas tribe recognised Abu Dhabi Island as its capital. During its early days, the fort stood ‘among a few crumbling houses built of coral and a hundred or so palm frond huts’. Abu Dhabi was described by one contemporary English commentator as:

A coastal town of about 6,000 inhabitants. There is a fort, and the houses are mostly built of date matting though some are of masonry. There is a small bazaar, and a poor anchorage. The water supply is from pits and wells, and is not very good. The supplies are particularly nil. There is usually no cultivation, and there are very few dates. Small quantities of cloth, rice, coffee and sugar are imported. There are about 750 camels and 65 horses.8

Throughout the 19th century, the Bedouin desert tribe continuously enjoyed access to the rich pearl beds of the Gulf coast, which helped the further evolution of Abu Dhabi as an emerging coastal town. Parallel to this flourishing of the city was of course the British presence. Britain had an imperial interest in India and it was also in her interest to protect the maritime area of the Gulf region and peace was necessary for business. As is highlighted by Muhammad Abdullah, ‘Abu Dhabi’s economic interests laid mainly in the date groves at Liwa and in the pearl fisheries around Dalma Island, far from the navigation channel of the Gulf, therefore the Beni Yas had no conflict with the British at sea.’9 The tiny sheikhdoms sparsely inhabited the southern shores of the Gulf Coast and for a long time were known as the ‘Trucial States’ due to the maritime truce drawn up between these tribes and the British Empire in the late-19th century. It was an arrangement that helped the city to prosper:

Abu Dhabi developed around the Qasr al Hosn and local construction material was used to build the surrounding housing areas. Ihilati and Ibarastii were the typical architectural styles used to build the dwellings which consisted of local materials such as clay, coral, sandstone, sea stone, palm trees and wooden pillars connected together with ropes.10

Later on, Abu Dhabi’s pearl trade was devastated by the marketing of Japanese cultured pearls at a fraction of the cost of Gulf pearls. This situation, combined with the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s, had a disastrous effect on the town’s commerce.11 However, a dramatic turnaround for Abu Dhabi soon came with the discovery of a more precious resource: petroleum. ‘The discovery of oil and the signing of concession agreements initiated a process that would transform what was in essence a provincial backwater, a collection of mud huts, into a recognisable urban entity.’12

In 1953, Abu Dhabi Marine Areas Ltd obtained offshore oil concessions, resulting in substantial royalty payments. Following Abu Dhabi’s first oil exports in 1962, Sheikh Shakhbout – who was then the leader of the tribes in the local area – started developing social conditions in a progressive manner. A municipal department was established in Abu Dhabi with the responsibility for improving living conditions and ensuring provision of drinkable water supplies and accessible public health services. In the same year, Halcrow & Company (a well-known British consultancy firm, today known as Halcrow Group) was commissioned to produce a master-plan for the city’s urban transformation. As described by Yasser Elsheshtawy, this master-plan included a series of north-facing buildings, a new road network, and the provision to raise the existing ground level through dredging and land reclamation.13 The plan also proposed the demolition of all existing buildings except for Qasr al Hosn, two water distillation plants, a few schools, and a power station.14 Nonetheless, despite these ambitious large-scale proposals, it was also evident that Sheikh Shakhbout was resistant to the idea of Abu Dhabi becoming a modern state, as he was still in favour of preserving a traditional lifestyle. He refused, for example, ‘to generate electricity, with the exception of the palace which was lit using a portable electrical generator.’15

In contrast to Sheikh Shakhbout’s reluctance to transform the island town into a dynamic modern metropolis, the accession to power of Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan in 1966 altered and improved the urban development process. His leadership also brought political tranquillity and pride to the new nation to-be: ‘Sheikh Zayed’s known achievements in Abu Dhabi, his generosity to the other emirates, together with his outstanding personal qualities, made him a popular figure and an obvious leader.’16 Mohammed Al-Fahim further described the leader: ‘Sheikh Zayed’s name was known by everyone, his reputation as a fair and generous man was equally widespread. He was a fiercely patriotic man who loved his country and its people above all else.’17 In addition, ‘Sheikh Zayed strongly believed that the revenues that were being generated as a result of the oil royalties should be used to develop Abu Dhabi and to assist the native population.’18

In 1968, during this period of internal political transition and the rapid development of the city, the Gulf States experienced the withdrawal of the British presence due to the latter’s economic pressures back home.19 As was pointed out, ‘British withdrawal from the Trucial States meant the latter would be left without the umbrella of protection that had guarded the coastal area against external aggressors since 1892.’20 Concerned about possible conflicts with neighbouring countries, Sheikh Zayed was convinced of the advantages of pursuing the unification of the surrounding sheikdoms, although he had to overcome natural resistance and scepticism from the other ruling sheikhs. Ultimately, in 1971, the formation of the political union known as the United Arab Emirates was achieved – made possible by Sheikh Zayed’s vision of a unified country, as well as encouragement from Britain. The city of Abu Dhabi, now established as the capital of the UAE, expanded within its isosceles-triangle-shaped island situated just off the coast at 24° north, 54° east. The city’s urban palette continued to extend towards the mainland and onto surrounding islands, the latter consisting usually of geometrically-shaped pieces of land reclaimed from the sea. Today the Abu Dhabi Emirate is the largest of the seven Emirate states, since it includes Abu Dhabi Island and numerous smaller islands nearby along with regions to the west and east on the mainland: altogether it constitutes 87 per cent of the UAE’s total land area.21

7.2 Sheikh Zayed poster in Abu Dhabi central business district (CBD)

Concomitantly, Abu Dhabi underwent major urban change, with local inhabitants being asked to move from their traditional housing into newly constructed homes. Buildings from the early days of the settlement were demolished, as had been recommended by the initial Halcrow plan, and the city was re-zoned yielding to modernity. Government compensation was given to those families who had to be relocated, and the sum each family was paid to abandon its old dwelling was sufficient to build a new abode as well as set up businesses with the remaining funds.22 Al-Fahim describes his childhood in the city at that time:

7.3 Abu Dhabi Island

In five years the metamorphosis of Abu Dhabi occurred at lightning speed … While it took most countries decades to develop communications and transportation systems for example, we did so in a very short time. We had electricity by 1967, phones in 1972. Wherever we turned to, something was under construction – government buildings, homes, roads, telephone lines.23

Around the same time, the Egyptian engineer Abdul Rahman Makhlouf was invited by Sheikh Zayed to continue the plan proposed by Halcrow & Company. To achieve this goal, Makhlouf was appointed as Director of the Town Planning Department of the Abu Dhabi Emirate from 1968–1976, making him responsible for the planning of both Abu Dhabi and Al Ain. His scope included deciding on the locations of key buildings, marketplaces, and the infrastructure for the city.24 Makhlouf also introduced the concept of the ‘national house’, which aimed to aid the Bedouin citizens adapt to urban life. As described by Elsheshtawy, ‘the house consisted of a large one-storey structure of concrete blocks with open and closed spaces suited to the Bedouin traditions. Each had two bedrooms, a kitchen, bathroom, garden, courtyard and other open spaces and a wall to hide the women’s quarters.’25 There was also a particular concern to build new mosques and markets (souqs) located at walking distance from the major residential clusters.

7.4 Continuous refurbishing of street layouts in Abu Dhabi

The logic behind the city’s planning in this period, which is still recognisable today, demonstrated a strong reliance on imported western modernist planning principles. Wide grid-pattern streets with their emphasis on vehicle connectivity, an orientation towards methodical building processes, and the use of high-density tower blocks were some manifestations of what was believed to be the solution for Abu Dhabi’s urban development. However, this new need to maximize accessibility for motor vehicles undermined the original organic way of travelling around the island. The human-scale yielded to vehicle-scale, and informal narrower alleys gave way to broad roads: ‘While the streets in the traditional patterns reflected residents needs such as climatic comfort, privacy and security, the streets in the modern patterns disregard these aspects.’ As the city’s population increased, rising building heights became not only a design choice but also an urban design necessity. The need to accommodate commercial and trading activities as well as housing needs pushed building density up. Alongside this new architectural solution for a modern Bedouin city in Abu Dhabi, with its imported greenery and technological infrastructure, came air-conditioning systems. This also altered the way in which people conducted their lives and had a large impact in encouraging tourism.26

7.5 Average building height in Abu Dhabi’s CBD

7.6 Canyon-effect produced by the typical building threshold in CBD

In order for the city to expand according to its leader’s vision, and meet the demand for developable sites, the 1970s and 1980s brought extensive land reclamation for waterfront development. This increased the size of the island from its original 60 km2 to 94 km2 by 1994, making it 50 per cent larger. Abu Dhabi’s population also grew exponentially: in 1966 it had been only 17,000 people, but this then soared to 70,000 in 1972, following the country’s unification. ‘A remarkable increase mostly attributed to immigrants’, is how this population boom has been summed up.27 Following this period, and more particularly throughout the 1990s, the Khalifa Committee (named after Sheikh’s Zayed’s son, the current ruler of Abu Dhabi and the UAE) became responsible for building a large percentage of the city, and providing also for housing needs. Its aim was to densify development: ‘The current urban form of the city was strongly influenced by this policy since plots handed out were small, resulting in the construction of towers which are particularly evident in the city’s centre. Some 95 per cent of plots in Abu Dhabi range between approximately 25m × 15m to 30m × 30m, and were occupied by multi-storey buildings with an average height of twenty storeys.’28 This particular building endeavour, however, has produced a rather repetitive canyon-like urban character, with an intensive repetition of high-rise towers close to each other (see Plate 11).

In anticipation of reaching even more advanced achievements in the early-21st century, and continuing urban progress and development, the Emirate’s Executive Council decided to prepare a further master-plan for Abu Dhabi. Hence in 1988, the Abu Dhabi Town Planning Department – in collaboration with UNDP and various international consultants – came up with the Abu Dhabi Comprehensive Development Master Plan.29 While planning for the future, the government also used this to inform people about the new levels of acceptable and unacceptable urban lifestyle. For instances, it stipulated that Bedouin families who tethered camels and other animals outside their residences were now forbidden to do so. The planning agency in charge justified the new measures: ‘The decision aims at preserving the urban outlook of the city, where under the current modernization programme, gardens are springing up everywhere, including residential areas.’30 Thus, traditional customs were deemed as not in accordance with the implementation of ‘disciplined’ housing compounds and modern high-rise areas, such as where the foreigners live. Another key aspect of the new Abu Dhabi was the introduction of western building materials, such as concrete, steel and glass. Such construction materials made the raising of floor levels feasible, but relied heavily on centralised air-conditioning systems which introduced an entirely different relationship of people to their environment. Another undesirable result was the visual impact of air-conditioning units, as well as, more recently, the satellite dishes which continuously riddle the city’s facades and rooflines.

7.7 The coastline of Abu Dhabi seen from on high

In the analysis of John Fox, the effects of globalization were, and still are, rendered differently in the Gulf region compared to other parts of the world. Hence, despite the continuous external forces being introduced into social and economic life in the Abu Dhabi Emirate, the nation’s strong traditional familial structure has ‘developed receptive ways of synchronizing localism with globalism within the area … the traditional social structure persists to direct the changes, and serves to filter what is acceptable – working as a sort of indigenous conservatism.’31 But within the Gulf, however, there are also significant disparities between the evolution of even nearby cities. When compared to Dubai’s rapid urbanising phenomenon, Abu Dhabi has taken a more conservative approach to its urban expansion. While the ‘louder’ Dubai has developed an economy based on international commerce, opening its city to a more intensified urban and architectural resolution driven by other countries, Abu Dhabi (backed by Sheikh Zayed’s vision) stands closer to Arab-Gulf traditions, with an added tolerance and interest in modernization, and the cultural infusion of new kinds of people, ideas and technologies.

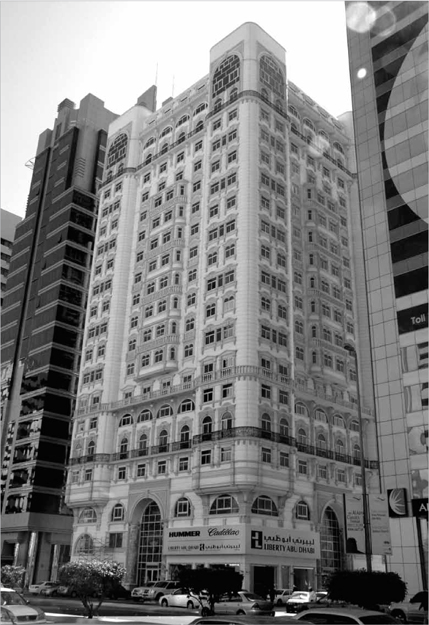

7.8 Pseudo-traditional architecture in Abu Dhabi

7.9 Dhow boat with Abu Dhabi skyline behind

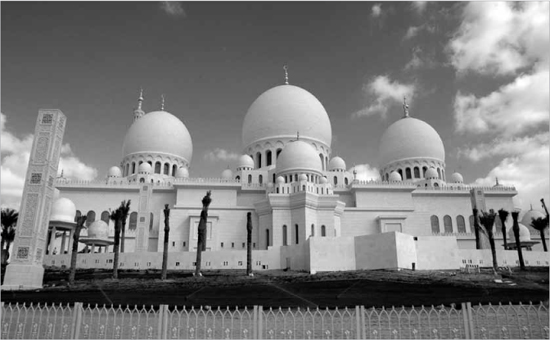

7.10 Grand Mosque (Sheikh Zayed Mosque), in Abu Dhabi, UAE

Religion is embedded in most social relationships in the Gulf, including the practice of capitalism. Only a small part of Gulf society sees capitalism as antithetical to the strong community values of Islam and have spawned anti-globalism political movements. The leadership constantly strives to show how tolerant Islam is as a religion so that globalization development may contribute bereft of indigenous reactions.32

In addition, Abu Dhabi has taken a strategic decision to emerge as a major international quality tourist destination. Large projects such as the Grand Mosque showcase the city’s desire to portray bold architecture that reflects the country’s Islamic religion, while at the same time symbolising the desirable institutional power for both the royal family and ordinary UAE nationals (see Plate 12).

THE GLOBAL ‘INSTANT’ CITY

The phenomenon of globalization, and its origins, is not necessarily of the 20th century, and indeed the concept of being ‘global’ seems to be constantly mutating. Back in 2000, Clark and colleagues explained the concept as being:

… the process of creating network of connections among entities at multi-continental distances, mediated through a variety of flows including people, information and ideas, capital and goods. Hence, globalization is conceptualized as a process that erodes national boundaries, integrates national economies, cultures, technologies and governance and produces complex relations of mutual interdependence.33

For the purpose of this essay, the concept of globalization is recognised as a multidimensional global event; it is a phenomenon that is experienced across the world and is ‘being driven by a combination of economic, technological, socio-cultural, political and biological factors.’34

Hence the presence of immigrants from skilled or unskilled background increased proportionally to the amount of new development that took place, and is still happening, in Abu Dhabi. Along with the new forms of architecture and the modern lifestyles freshly imposed on its people, new social dynamics have arisen from the introduction of ‘strangers’ who were vital to deliver the leader’s vision: ‘Oil-generated growth has literally demolished mud-walled small seaports and villages. In less than fifty years Abu Dhabi has transformed into a commercial capital with its sprawling suburbs integrated within the global economy and culture.’35 The advent of the 21st century has brought even further transformation. Hundreds of low-rise buildings from the early-1970s are currently being demolished and replaced by high-rise blocks. There are also strong moves to improve the landscaping. According to the Abu Dhabi Municipality, the city has, since its inception, undergone an extensive forestation process including the planting of parks and tree-lined boulevards with evergreens and literally millions of palm trees.36 Certainly, the municipal statistics from 2003 reveal that there were then about 80 million trees in Abu Dhabi.

7.11 Continuous demolition in Abu Dhabi

Despite the current prolonged global economic recession, Abu Dhabi continues to move ahead with high expectations; its current total value of announced projects is close to the AE Dirham1,835 billion (US$ 77 billion) mark.37 According to the Abu Dhabi Emirate’s yearbook in 2009, its status as an emerging market is highlighted by the large investment being poured into real estate, tourism and leisure. Developments such as Masdar City, Capital District, Saadiyat Island, Yas Island, Al Suwwah Island, Al Reem Island and Al Raha Beach represent Abu Dhabi’s ambition to become a capital not only for its country, but also for culture, education and research within the Gulf as a whole. The city is setting new standards in building, urban planning, design and cultural development. In 2007, therefore, Abu Dhabi’s government announced a modified master-plan, an urban structure framework for the city during its rapid urban evolution, which would showcase its vision as a world-class leader in creating an innovative and sustainable Arab capital city. Thus the ‘Plan Abu Dhabi 2030’ delineates the official framework for substantial development across the entire Abu Dhabi metropolitan area, providing the vision for all aspiring projects.38 There are five central principles which inform the plan’s ideas and policies, but the imperative goal is for Abu Dhabi to be ‘a contemporary expression of an Arab city’, with its inhabitants thriving in the supportive and healthy community which Abu Dhabi will ultimately become. In addition, another key element lies in the importance for Abu Dhabi to continue to practice measured growth as part of a sustainable economy, with the master-plan recognising the significance of environmental sustainability and the need to respect the city’s sensitive coastal and desert ecologies.

The ‘Plan Abu Dhabi 2030’ addresses concerns for a more coherent matching of built form with social and functional needs. Abu Dhabi has a particularly unique real-estate allocation system in which land ownership is granted exclusively to every male head of an Emirati family. As a result of this process, it becomes imperative to provide adequate housing for the evolving needs of Emirati families, and to reduce the waiting time for receiving government sponsored dwellings by increasing their availability. Hence the plan offers guidelines for building blocks designed around specific needs of UAE nationals:

These include the fareej – modelled on a set of villas around a central courtyard, reflecting an extended Emirati family structure – as well as island and desert eco-villages. The villages are based on traditional Emirati ways of life, and the aim is to ensure these environments are provided across the emirate in a way that reflects local customs. Sustainability initiatives such as solar and wind power will also make these communities more self-reliant in the future.39

EMPIRICAL DATA ABOUT ABU DHABI

Taken altogether, the UAE’s population increased by 74.8 per cent from 1995–2005, with the Ministry of Economics predicting this figure would reach a total of 5.06 million people by the end of 2009. The discrepancy between nationals and non-nationals, however, is extremely noticeable: ‘a breakdown of the 2007 figures indicates that there were 864,000 UAE nationals and 3.62 million expatriates in the country.’40 Within the UAE, Abu Dhabi was the most populous state in late-2007, with 1.493 million people. However, the population in the Abu Dhabi Emirate when divided by gender at this date was 982,000 males and 511,000 females, the difference being because of the high numbers of male immigrant workers. There are also very sharp economic divisions. According to the Department of Economic Development, the average monthly income of Emirati households in Abu Dhabi in 2008 was Dh47,066 (12,815 USD), but the average monthly income in the same year for expatriate households – mostly overseas labourers – was Dh15,000 (4,084 USD).41 This social division is even greater when one realises that the Emirate’s per-capita income surged from around Dh76,600 (20,856 USD) in 2006 to Dh162,000 (44,107 USD) in 2007, with the overall gross domestic product increasing from Dh624 billion to Dh729 billion in the same period.42 The key areas influencing this rapid economic growth were – from the UAE Central Bank’s statistics – the astonishing boom in the construction sector (25.6 per cent rise) along with significant growth in manufacturing and industry (19.8 per cent); real estate (16.9 per cent); finance (11.5 per cent); transportation and communications (8.3 per cent), and tourism, which continued its steady growth by growing by 6.4 per cent in terms of trade volume. Exact and up-to-date data is hard to obtain, but certainly recent statistics suggest that these demographic and economic trends still hold true for Abu Dhabi. In estimates from mid-2009, the city had around 970,000 citizens, some 60 per cent of the Emirate’s population, with two-thirds of them being male. Emiratis continue to comprise just 20 per cent of Abu Dhabi’s populace.43

ANALYSIS – THRESHOLD MATRIX

The impact of globalization in the contemporary Abu Dhabi built environment can be analysed through the lenses of issues of privacy, physical walls and the notion of gate. In order to do so, tangible and intangible thresholds in the city can be categorized into the tangible physical urban design (such as gated communities) and architecture (gated villas and high-rise towers); as well as the intangible notions of exclusion by the presence of walls and gates.

7.12 Threshold matrix – Layer 01

The proposed 3D-threshold matrix analyses Abu Dhabi’s current urban design and architecture. This matrix consists of a model with three axes (x, y, z) which consequently form eight planes that can be juxtaposed in either two and/or three dimensions. The data analysis was limited to the following three parameters: architectural expression (whether contemporary or traditional); economy (global or local/regional); and Arabic cultural traditions/interfaces (such as open/inclusive and. closed/exclusive). The investigations produced four typical strands within Abu Dhabi’s current urban realm. They consist of: ‘alienated hyper-modernism’, ‘contextual globalism’, ‘fairy-tale traditionalism’ and ‘eco-minded contemporary traditionalism’. By following the global side on the economy ‘Y’ axis (as in societies open to external influences) and the architecture side on the ‘X’ axis (contemporary or traditional) on the first layer of the matrix, we were able to trace an apparent pattern of current and future architectural trends which respond to two major attitudes towards globalism. The findings were then further elaborated:

1 Alienated hyper-modernism (mid-2000s to date)

This concept is characterized by a hyper-dense master-plan with building heights ranging from 40–80 storeys. Its street pattern tends to be of a previously modified grid, catering for motor vehicles, with a resulting disconnected public realm. As a consequence, the scale of buildings and their podiums façade treatment (for multi-storey parking garages) do not contribute towards an enjoyable pedestrian realm. In most cases, the individual structures have fully or partially controlled access to their own amenities/park areas, and/or stretch of waterfront. The Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council currently addresses issues caused by this type of design proposal with the aim to safeguard quality urban space for public use, ensure urban connectivity across the city and influence the quality of the city’s public realm.

Most of the proposed buildings which fall under this sub-category consist of reinforced-concrete structural frames clad with glazed curtain wall. In the context of Abu Dhabi, this architectural solution does not consider basic principles of building massing or vertical/horizontal articulation. The harsh microclimate and building physics (i.e. high sun exposure, sand accumulation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and the need for energy preservation) tend to challenge any architectural proposition. In addition, this kind of hyper-modern architecture tends to ignore its context, particularly at ground level, and as a result, it creates human isolation and denies a desirable human scale within the city’s public realm. Arabic motifs are rarely incorporated into the design process, and when Arabic identity is addressed, it is usually expressed through a simplistic interpretation of the mashrabiya form.

Occasionally, there are more complex, sophisticated and innovative architectural elements that do not necessarily contribute to an inclusive pedestrian urban experience but its geometries and avant-garde design demands a certain level of recognition. Examples of buildings at this end of hyper-modern typology include the proposed works by Jean Nouvel and Norman Foster for emerging developments on Saadiyat Island. Another example is the recently built tower for the Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre (ADNEC).

2 Contextual globalism (mid-1980s to mid-2000s)

At a master-plan level, this sub-category is characterized by mid-to-high density buildings with a maximum height of 25 storeys. The street grid is likely to be tight, as in the case for the superblocks in Abu Dhabi’s central business district. The urban design patterns are clearly modernist, more specifically of the ‘tower in the park’ typology. These typologies are usually based on three layers of developments: higher individual towers forming a perimeter block, mid-height towers that create the first row of inner blocks, and then two-storey villas or four-storey multi-complexes that fill the core of the block. The street patterns are disjointed, typically confusing, and seemingly every inch of public space is populated by parking lots. An absence of a coherent pedestrian realm and severe challenges to accessibility are distinctive of this typology.

7.13 Contextual globalisation in Abu Dhabi

Architecturally, the building lines are clear, and façades present minimal articulation. The use of glass curtain walls tends to be pervasive, with superficial application of generic ornamentation without proper referencing of Arabic arts-and-crafts traditions. The late-1990s and early-2000s brought a few sophisticated examples whereby modernism was balanced with strong references to regional Arabic architecture. This typology is particularly represented in Abu Dhabi’s central business district, but can also be seen in newer suburban neighbourhoods. In some of the latter, cultural and environmental sensitive housing proposals of contemporary courtyard housing have the opportunity to add positively to the not successful aspects of this typology.

The previously discussed subcategories refer to a global scale. The ‘Y’ axis, which covers the local/regional mode showcase the emergence of two different trends:

3 Fairy-tale traditionalism (1990s to date)

This typology is the result of two influential forces: firstly, reluctant clients who wish to deny the embracing of global modernism, and are typically inclined towards the popular expression of regional architectural features; and secondly, the lack of professionalism and quality control present in the architectural and engineering field available in Abu Dhabi. The professional body that is responsible for delivering meaningful architecture in Abu Dhabi has not been diligent and is partially responsible for the widespread of architectural work favoring superficial Arabic geometric form. In this sub-category, the buildings showcase an inaccurate and artificial localized style, if not indeed a kitsch version of refined traditional Arabic architecture. Therefore, the kind of building produced does not in any sense represent the original aspirations of Arabic architecture. This typology has now spread all over Abu Dhabi in the form of typical villa housing or other more exuberant building typologies such as hotels. The Emirates Palace Hotel can be seen as a high-end, slightly more crafted expression of this fairy tale tendency.

7.14 Fairy-tale contextualism

7.15 Some more fairy-tale contextualism in Abu Dhabi’s CBD

4 Eco-minded contemporary traditionalism (current)

This last sub-category represents a critical and intriguing new threshold within the urban evolution of Abu Dhabi. It reflects the elevated confidence of visionary leadership and evolving strategic planning of Abu Dhabi’s government, which is committed to incorporating sustainable practices in its city-making process. This increased awareness prioritizes an interest in traditional and compact urban Arabic relationships (such as pedestrian-oriented streets), a contemporary interpretation of the principle of fareej (as a social urban component, with each neighbourhood acting as a playground for the traditional Emirati extended family), and finally a revival of courtyard housing concepts (including privacy, contemplation and safety).

In conjunction, this sub-category is being driven by microclimatic issues, involving the basic elements of survival in such a harsh desert climate, and the growing global issue of energy availability. It is well known that methods of energy conservation and on-site energy production are currently being addressed by many countries across the globe. An emphasis on public transport and human-scale urbanism are also being brought to the forefront of this typology. Its architectural components tend to accentuates both modernity and tradition through a contemporary reinterpretation of Arabic architectural forms and elements. At the same time, such commitment to sustainable development provides a functional solution to the sustainability agenda, and this trend is well represented by the construction of Masdar City.

7.16 Threshold matrix – Layer 02

After identifying these four trends, the analysis continued to the ‘Z’ axis, which deals with Arabic cultural traditions/interfaces. The prime interest lies in investigating the extent of its influence on the urban and architectural scales of Abu Dhabi after over 40 years of global exposure. The subject of ‘threshold’, as an interface between the private and public realms, is of fundamental cultural and spiritual importance to the Emirati population, as well as to the other present nationalities who are Muslims. There are important social, spiritual, psychological, cultural and physical/architectural interpretations of the meanings of ‘wall’ and ‘gate’ within Arabic culture. As Anwarul Islam and Naval Al-Sanafi note: ‘Invasion of domestic privacy in Islam is discouraged by a formidable system of religious, legal and social prohibition so that the house entrance – the vulnerable threshold between the household and the public – is accorded particular symbolic importance.’44

7.17 Interface 1

7.18 Interface 2

The notion of privacy is present in Abu Dhabi within its: urban design (neighbourhood, urban block) and its architecture (outer wall, the gate/entry point, and inner building wall). The importance of this classification lies in the fact that traditional Arabic houses were designed with limited exposure to the outer ‘world’, as the houses were opened towards an internal courtyard instead of a public street. Dwellings were window-less, or had a limited number of carefully sized and specifically located apertures which served other functions. Rapid globalization, however, introduced dramatic changes in social life and architectural morphology in the Gulf region, as Yassine Bada explains:

In both types of transformations, windows appear on the external facades, which were originally windowless. These windows are not only used for their prime role of lighting and ventilation, but are also a medium for people to appear on the social scene as modern and progressive. Windows are often the first sign of the beginning of individualization and reorientation of the house to the public space, and a symbol of rejection of deep-rooted cultural/religious imperatives. It is also the result of a new urban organization where the houses are not clustered in the traditional way.45

Hence the notions of interface between private and public realms are much more complex nowadays in cities such as Abu Dhabi, and as such these thresholds vary greatly in scale and morphology, to an extent that would have been difficult in earlier generations.

7.19 Corniche panorama in Abu Dhabi

7.20 Aerial view of Masdar City on the edge of Abu Dhabi

Table 7.1 Classification of design approaches and building features in Abu Dhabi

It has not been possible to amend this table for suitable viewing on this device. Please see the following URL for a larger version http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781409470984Tab7_1.pdf

CONCLUSION

Abu Dhabi’s urban evolution timeline has been compressed since its inception and it continues to be challenged by a harsh climate and ever-insistent globalising forces. Political, economic, social and cultural factors have contributed to Abu Dhabi’s cautious, but informed, urban leadership in all those aspects. A wise conservativism has ensured the continuity of a strong national identity while also reinforcing the image of the city as the capital of a progressive Arabic society. Urban planning and architecture played important roles throughout this story. As a result of the continuous state of change, and an aspiration for improvement, Abu Dhabi embraced several ‘foreign’ design proposals which were – over time – counterpoised and blended with more local/regional Arabic design considerations. This fusion of avant-garde international modernism with Arabic traditionalism has produced a profound change in attitudes towards housing and public realm design, in particular in regard to the issue of privacy levels. Our analysis demonstrates that despite what appear to be dramatic shifts in formal planning and architectural paradigms, resulting in the creation of new building forms and thresholds, Abu Dhabi’s society continues to find ways to adjust to these contemporary demands while celebrating Arabic-Emirati culture. Under its visionary political leadership, and a maturing approach to planning and architecture, Abu Dhabi is on the brink of truly becoming a leader in the creation of sustainable living urban environments, through initiatives such as Masdar City. In many respects, Masdar’s low-energy vision synthesizes internationally-available technologies with a deep understanding of local climate and local Emirati wisdom; and as such, it symbolizes Abu Dhabi’s newest threshold into the future.

NOTES

1 John Fox, Nada Mourtaba-Sabba & Mohammed Al-Murtawa (eds), Globalization and the Gulf (London/New York: Routledge, 2006).

2 Samuel B. Miles, The Countries and Tribes of the Persian Gulf (London: Ithaca Press, 1919), p. 443.

3 Jayanti Maitra & Afra Al-Hajji, Qasr Al Hosn: The History of the Rulers of Abu Dhabi, 1793–1966 (Abu Dhabi: Centre for Documentation and Research, 2001), p. 4.

4 A. de Lacy Rush (ed.), Ruling families of Arabia (Vol. 1, UAE: Archive Editions, 1991), p. xix.

5 Maitra & Al-Hajji, Qasr Al Hosn, p. 9.

6 Richard Trench, Arab Gulf Cities (Slough: Archive Editions, 1994), p. 132.

7 Maitra & Al-Hajji, Qasr Al Hosn, p. 1.

8 Ibid., p. 47.

9 Muhammad M. Abdullah, The United Arab Emirates, a Modern History (London: Croom Helm, 1978), p. 96.

10 Abu Dhabi Municipality & Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi, Dana of Gulf, Planning and Urban Development Studies and Research Centre (UAE: Abu Dhabi Municipality, 2003), p. 22.

11 Maitra & Al-Hajji, Qasr Al Hosn, p. 12.

12 Yasser Elsheshtawy (ed.), The Evolving Arab City: Tradition, Modernity and Urban Development (London/New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 265.

13 Ibid., p. 266.

14 Abu Dhabi Municipality & Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi.

15 Elsheshtawy, The Evolving Arab City, pp. 264–267.

16 Abdullah, The United Arab Emirates, p. 140.

17 Mohammed Al-Fahim, From Rags to Riches: A story of Abu Dhabi (UAE: Makarem Trading and Real Estate, 2007), p. 130.

18 Ibid., p. 133.

19 Abdullah, The United Arab Emirates, p. 323.

20 Al-Fahim, From Rags to Riches, p. 148.

21 Abu Dhabi Municipality & Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi.

22 Al-Fahim, From Rags to Riches, p. 140.

23 Ibid., p. 137.

24 ‘The master planner of Abu Dhabi, Al Ain’, March 2007, Khaleej Times website, http://www.khaleejtimes.com/DisplayArticleNew.asp?section=theuae&xfile=data/theuae/2007/march/theuae_march284.xml (accessed 31 August 2009).

25 Al-Fahim, From Rags to Riches, p. 269.

26 Ann Coles & Peter Jackson, Windtower (UAE: Stacey International, 2007), p. 4.

27 Fred Halliday, Arabia without Sultans (London: Saqi Books, 2002).

28 Elsheshtawy, The Evolving Arab City, p. 272.

29 Abu Dhabi Municipality & Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi, p. 55.

30 Fox, Mourtaba-Sabba & Al-Murtawa, Globalization and the Gulf, p. 211.

31 Ibid., p. 9.

32 Ibid.

33 Quoted in Axel Dreher, ‘Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from a new Index of Globalization’, Applied Economics, vol. 38, no. 10 (2009): 1091–1110 (accessible at http://globalization.kof.ethz.ch/static/pdf/rankings_2009.pdf).

34 Sheila L. Croucher, Globalization and Belonging: The Politics of Identity in a Changing World (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), p. 10.

35 Fox, Mourtaba-Sabba & Al-Murtawa, Globalization and the Gulf, p. 247.

36 Abu Dhabi Municipality & Town Planning Department, Abu Dhabi, p. 41.

37 Peter Vine (ed.), United Arab Emirates Yearbook 2009 (London: Trident Press, 2009), p. 146.

38 Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council, Plan Abu Dhabi 2030, Urban Structure Framework Plan (Abu Dhabi: UPC, 2007), pp. 15–16.

39 Vine, United Arab Emirates Yearbook 2009, p. 150.

40 Ibid., p. 206.

41 ‘Average Emirati household income in Abu Dhabi is Dh47,066’, Gulf News website, http://archive.gulfnews.com/business/General/10329531.html (accessed 12th August 2009).

42 Vine, United Arab Emirates Yearbook 2009, pp. 57–58, 206.

43 ‘Abu Dhabi has over 1.2 million expatriate residents’, Emirate 24/7 website, 26 September 2010, http://www.emirates247.com/news/emirates/abu-dhabi-has-over-1-2-million-expatriate-residents-2010-09-26-1.295398 (accessed 23 November 2012). Similar, yet slightly different, figures are given in CIA, ‘The World Factbook – Middle East: United Arab Emirates’, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ae.html (accessed 23 November 2012).

44 Brian Edwards, Magda Sibley, Mohamad Hakmi & Peter Land (eds), Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and Future (Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2005), p. 91.

45 Ibid., p. 215.