ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM AND BUILDING PERFORMANCE EVALUATION IN GERMANY

Introduction

The analysis of the built environment occurs at different levels of reasoning. On one hand, there are building standards, complex building legislation, and recently created certification systems for sustainable building, including related assessment methods like post-occupancy evaluations (POE). Taken together, these guarantee a very high level of building technology in Germany. On the other hand, and from the perspective of design, things look different. Banality, wrong buildings in the wrong places, urban misconception, neglected infrastructure and structures that were built after World War II, are just some of the issues that need to be addressed and thought through by an architectural criticism that is relevant for society. Here, architectural criticism has to be seen as a propaedeutic tool for architectural theory.

The growing constraints of the economy, however, threaten the freedom of the press, too, especially in the building sector. This problem is complicated by criticism in a context that is constantly changing. For example, due to the growing importance of participatory planning processes, architecture criticism increasingly targets the layperson in order to counter populist arguments, among other things.

Architectural criticism

Architectural criticism until 1975

In a narrow sense, the history of architectural criticism goes back to the eighteenth century, to the early days of the print media (Arnulf 2004; Fuhlrott 1975; see also Chapter 9 by Nussaume). Initially, amateurs and educated connoisseurs of architecture discussed the beautiful and appropriate, the charming and tasteful. Starting in France, the professional discourse focused on the tension between tradition and modernity, and it remains connected to cultural spheres which initially included the new profession “civil engineer” (Philipp 1996; Froschauer 2009; Schnell 2005). Later on, architectural criticism evolved methodologically in separate circles of experts and laypeople. This happened after the history of art and architecture was established methodologically as a discipline in a collective unit. Early architectural articles were published in bourgeois Germany by civil engineering authorities, for example the Journal für die Baukunst (Journal for the Art of Building, since 1829). Next were journals like the Deutsche Bauzeitung (German Building Journal, since 1865) or Der Baumeister (The Builder). Descriptions, knowledge, manifestos, criticism, and propaganda formed a spectrum where architectural criticism emerged and evolved into a discipline. In the twentieth century, architectural criticism came under the influence of the construction industry, which supported an advertising clientele as the economic base for architectural magazines and also the daily press.

The critical investigation of architecture happened in journals through a positive selection which was not representative of the actual construction process. Professional criticism was largely characterized by the demands of Ulrich Conrads. For decades he served as editor-in-chief of the weekly magazine Bauwelt (World of Building), and he expressed himself in rather strong terms (Conrads et al. 2003; Ciré and Ochs 1991; Kemp 2009; Dechau 1998). Throughout, it has also been imperative for all critics to acquire as much as possible of the available onsite knowledge about a building, and to put it into a larger context of everyday building activities. These were consumed by endless and stirring debates about functionalism within the construction industry. They remained largely excluded from criticism, i.e. excited exchanges about individual projects, which in this context can hardly be described as criticism.

In the second half of the twentieth century, as the implementation of the car-friendly city threatened old neighborhoods, criticism of architecture and urban planning in the daily press started to concern itself with existing buildings, culminating in the architectural heritage year in 1975 (Colquhoun 1985; Flagge 1997).

Architectural criticism in the twenty-first century

The speed with which communication shifted to the internet in the last decades has driven journals into architecture-critical insignificance and economic ruin – a development whose consequences cannot yet be foreseen (Baus 2012a). The real estate industry capitalizes on architecture and urban planning which is increasingly uncontrollable by the community, and is rarely guided by policy. Certification systems for sustainable building (see also Chapter 24 by Walsh and Moore) result in improving building quality to a certain extent, but are also awarded to buildings that are dysfunctional, inappropriate from the perspective of urban development, and extremely banal and ugly.

While architectural criticism could deal with paradigm shifts and problems of pluralistic architectural philosophies (Baus 2012b), it has conflicts with the logic of the construction industry: Even if architectural criticism clearly denounces the extensive destruction of cities by demolition and new construction, it is in no position to deal with the interests of the real estate industry as criticism becomes less important, not only with respect to content, but also in the media and in reality. It is not only the internet which has the potential of engaging end users in an efficient manner who want to and are capable of influencing the development of their built environment using participatory methods. Laypersons know that they have a fighting chance in the political context.

This development mirrors Rambow’s argument: “It is not enough to understand architecture only as an object of the ‘feuilleton’” (i.e. feature pages in the daily press) (Rambow and Moczek 2001), a point that he made in one of the very few articles about “building evaluation” that were published at all in the Deutsches Architektenblatt (German Architechts’ Journal). Instead of a specialized criticism within closed circles of experts long before a building is utilized, Rambow calls for an evaluation of the building that focuses on its functioning during occupancy. This kind of assessment respects – in many cases for the first time – laypeople’s experience with architecture and “explains the role of architecture for a humane environment” (Rambow and Moczek 2001). In general, this relation between man and his (built) environment is the science area of a relatively young discipline in Germany, called “Environmental Psychology” or, more specifically, “Architectural Psychology.” While this discipline was underdeveloped in the 1970s compared to the US (Preiser 1972), today, several institutes and organizations, both in the public and private sector, conduct externally funded research projects or perform building evaluation as part of their range of services: “In contrast to architectural criticism POEs are based on empirical data, implying more than the mere reflection of individual critics and they consider many more aspects than only aesthetics” (Schuemer 1998). Nowadays, building performance evaluation is a complex issue within the German construction industry that is becoming more and more significant.

Building performance evaluation

The performance concept in the building life-cycle

In Germany – as well as in other German language areas – the scope of work and the performance of a building is traditionally well described in the form of bid documents. Aside from the project-specific quantified codes, numerous trade-related national, European, and international codes (DIN – Deutsches Institut für Normung/German Institute for Standardization; CEN – Europäisches Komitee für Normung/European Committee for Standardization; ISO – International Organization for Standardization) and all kinds of building regulations (BauGB – Baugesetzbuch/Building Code; VOB – Vergabe- und Vertragsordnung für Bauleistungen/Procurement and Contract Procedures for Building Works; EnEV – Energieeinsparverordnung/Energy Saving Ordinance etc.) need to be met during the building delivery process. With the advent of “facility management” in Germany in the mid-1990s, the traditional linear process of building delivery was gradually supplanted by the building performance evaluation (BPE) model (Preiser and Schramm 1997). It presents a holistic understanding of planning, programming, design, construction, occupancy, and recycling, including related review loops (see Figure 1.3, Chapter 1). Therefore, the evaluation of building performance doesn’t any longer exclusively take place at the end of construction in the form of technical quality control or aesthetic architectural criticism. Nowadays, a building’s performance is increasingly reviewed throughout its entire life-cycle, phase by phase, taking both the quality of the object, and more and more the quality of the process into consideration as well.

Good examples of this kind of quality control are the certificates of energy performance and of sustainable building.

Energy efficiency as critical factor

A milestone in the shift from the linear building delivery process to a holistic understanding of the building life-cycle was the oil crisis in 1973. The issue that oil is a limited resource suddenly became obvious to the German population: Four “car-free Sundays” introduced by a Federal law resulted in empty streets and highways. People realized that energy savings and efficiency were the requirement of the moment for both mobility and building.

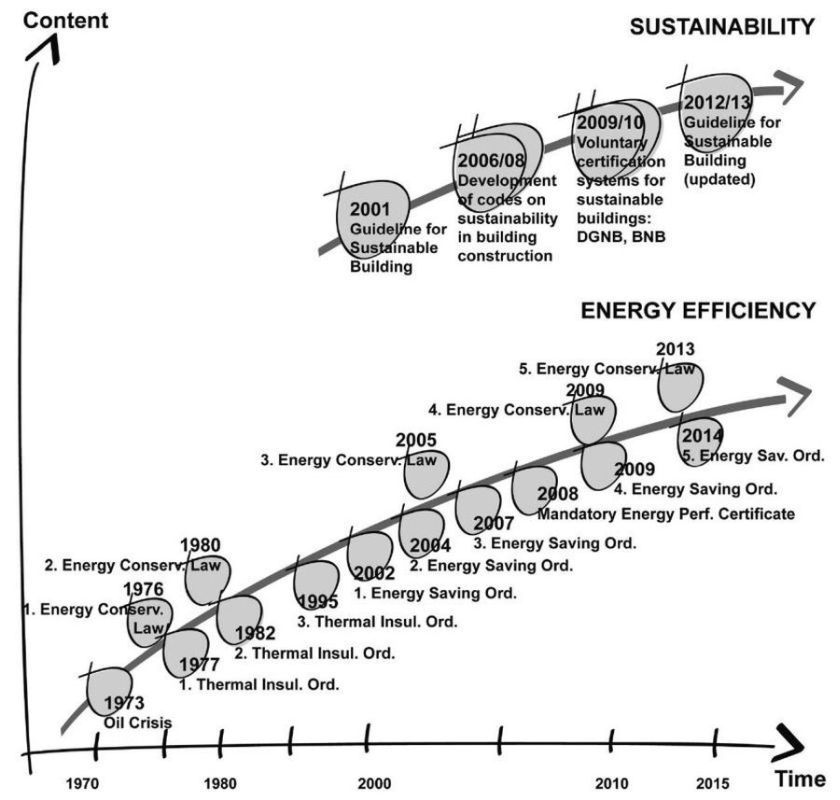

FIGURE 10.1 Development of the policy for energy-efficient and sustainable buildings in Germany

Source: diagram by U. Schramm based on http://www.enev-online.de and http://www.enev-online.de and http://www.nachhaltigesbauen.de

In 1976, the First Energy Conservation Law facilitated the issue of the First German Heat Insulation Ordinance focusing on the energy performance of new buildings. A series of laws and ordinances followed during the next several years (see Figure 10.1), thus continuously updating the requirements for energy savings. The next ordinance, to be published in 2014, will adopt the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), published by the European Commission in 2010: “The EPBD requires member states [like Germany] to ensure that by 2021 all new buildings are so-called ‘nearly zero-energy buildings’” (European Commission 2013).

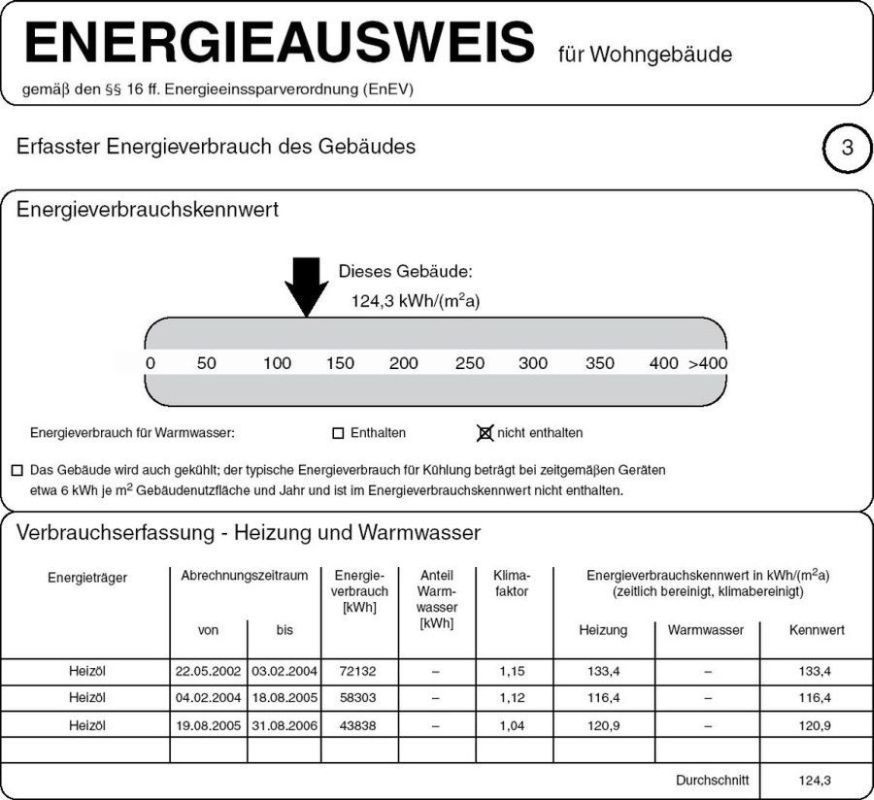

Furthermore, the instrument of an energy performance certificate will be strengthened. Introduced in 2002 for new buildings and in 2008 for existing facilities which are on the market for sale or for rent, the certificate benchmarks the individual energy performance of all buildings (see Figure 10.2). In 2014, when the next ordinance will be published, such a benchmark has to be included in property advertisements (e.g. in the daily press). It will even be posted in the entrance area of public buildings, such as town halls or movie theaters. With this step, energy efficiency will no longer be an issue for architects or engineers alone when they plan and construct a building, but also for clients, building occupants, and the public when they use it. Thus, energy performance evaluation is relevant throughout the entire building life-cycle. Using objective and measurable criteria, the evaluation serves as quality control and sensitizes many people involved in the life-cycle of a building.

FIGURE 10.2 Example of an energy performance certificate, based on the real energy consumption of a residential building during occupancy, indicating a benchmark of 124.3 kWh/m2a

Source: U. Schramm with energy consultant U. Schreiner.

Sustainable building as leading issue

While energy efficiency has been one of the major critical factors concerning building performance evaluation for the last 40 years, today “sustainability” has become the leading issue in the German building sector.

In 2001/2, and following international reports, research studies, and conferences, the German Federal Government enacted the national sustainability strategy “Perspectives for Germany” and published the Assessment System for Sustainable Building (Federal Ministry 2011). Besides energy-related aspects and other ecological requirements, current economic and socio-cultural criteria also need to be considered in the context of sustainable building. Following international assessment systems like BREEAM in the UK (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) or LEED in North America (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), several certification systems for sustainable building have been developed in Germany since 2009: the DGNB-label for the private sector (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen/German Sustainable Building Council), supported by the real estate industry, and the BNB-label for federal buildings of the government (Bewertungssystem Nachhaltiges Bauen für Bundesgebäude/Assessment System for Sustainable Building for Federal Buildings) are the most popular ones.

FIGURE 10.3 Federal Environment Agency, Dessau, 2005 DGNB-Certificate: “Gold,” RIBA award, Deutscher Architekturpreis: High Commendation

Source: Wikipedia Commons, February 28, 2014.

Out of some 50 criteria, the DGNB/BNB systems constitute profiles in these categories: (1) ecological, (2) economic, (3) socio-cultural and functional, (4) technical, (5) process quality, and (6) location. They contain the description of the criterion, the sub-criteria and the relevant indicators. Moreover, “Design and urban quality” are the only criteria related to the architectural quality of a building contributing 2.5 percent of the overall assessment result. Both assessment systems are primarily planning-based systems (Federal Ministry 2011). This means that most of the evaluation takes place before the utilization phase begins, only based on simulation or modeling and sometimes with surprising results: Matthias Sauerbruch, architect of the award-winning Federal Environment Agency in Dessau (see Figure 10.3), reports that the total primary energy demand of the building during the first year of occupancy was twice as much when compared to the expected performance data from modeling during the design phase (73 kWh/m2a). The analysis showed three reasons for this (Meyer 2012):

1 Simulations are based on average values. In reality, weather and seasons vary every year.

2 Innovative technology occasionally does not work as expected from the very beginning. Here, the solar cooling system on the roof had to be replaced by a temporary, mobile system with extremely high power consumption.

3 User behavior is difficult to predict, especially because of the turnover of employees. By constantly highlighting the energy saving features of the building to the employees, the energy consumption went down (85 kWh/m2a) after five years of occupancy.

In this context, it becomes obvious that assessment systems for sustainable building have to be used not only as tools for quality assurance as part of planning and quality control at the construction site, but also in the evaluation of success in building operations. Besides the monitoring of performance data, it is consistent to include in the BNB-assessment system the phase of building occupancy, for example, by measuring the index of actual user satisfaction: Here, a standardized questionnaire, which will be available online in a short and long version, needs to be filled out at least every four years, separately for the summer and the winter season (BMVBS 2013a).

With such tools, POE as a well-established methodology of performance evaluation during the utilization of a building became part of the federal assessment system for sustainable building BNB. Since 2011, this system is mandatory for all federal buildings in Germany and reflects the “Assessment System for Sustainable Building.” This guideline was updated and reintroduced by law in 2012, and it specifies minimum levels of building performance (e.g. 65 percent performance = silver level). The guideline is published by the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development, is mandatory for all federal buildings, and it supports POE as a form of managing success with a focus on the actual user behavior (BMVBS 2013b). Thus, building users’ feedback is expected to be part of a sustainable development. Incidentally, this is the first time that the English term “post-occupancy evaluation” (POE) has been used in an official guideline of the Federal Ministry in Germany.

Active participation as part of Baukultur (culture of building)

Having “user satisfaction” as a major criterion, the POE methodology and the BNB system are two examples of building performance evaluation (BPE).

For many years planning regulations in Germany have included some formal procedures for public participation in general. After several controversial debates about building and infrastructure projects like “Stuttgart 21” (see Figure 10.4), when tens of thousands of local residents opposed plans to build a modern transportation hub, today even the Federal Minister of Transport, Building and Urban Development, Peter Ramsauer, admits the need for more direct participation of the citizens with real influence on the planning process (Ramsauer 2013).

In this context, participation does not mean some input in the social media – such as “like” or “dislike.” As building processes are too complex, they require active participants taking individual responsibility and a critical look at the project in question. Thus, Socrates’s reminder is still true today: “It is foolish to talk about something without knowing it” (Miessen 2012; Frielinghaus 2013). Now, manuals for a meaningful participation of citizens are published even at the federal and state ministry level. They offer a broad range of instruments depending on the varying goals of dialogues: for example, “Flyers” if the goal is information, “Focus Groups” if there is need for discussion, or “Round Tables” if consultation for finding solutions is required (BMVBS 2012; MWEIMH 2012).

The potential for participation throughout the building life-cycle is enormous: on one hand, in terms of both the subjective perception and process quality, and the objective quality of the results on the other. Experiences with participatory processes result in, among other things:

• fewer conflicts;

• better behavior of consensus;

• stronger identification with the changed urban context;

• more confidence in public administration and policies;

• better understanding of democracy;

• better understanding of good design;

• better buildings, as local citizens are often appropriate and knowledgeable experts regarding location, history and everyday life (Frielinghaus 2013).

Participation as part of building performance evaluation combines the expert knowledge of building users, their creativity, and their individual interests with the work of building professionals like planners, architects, facility managers, or even architectural critics. This may result in higher quality processes, improved buildings, and greater acceptance by occupants and the public. Thus, both participation and evaluation throughout the building life-cycle improve the performance of buildings and are part of what is called Baukultur (culture of building) in Germany today (Frielinghaus 2013).

FIGURE 10.4 Demolition works and protest demonstration at the north wing of Stuttgart’s 100-year-old train station

Source: Wikipedia Commons, February 28, 2014.

Conclusion

Earlier in this book, Tom Fisher observed that in the US and even in terms of a global perspective, “Architecture criticism is in danger of disappearing at the very moment when we need, more than ever, a searching and sustained critical conversation about the built world” (see Chapter 7 by Fisher). This is is true in Germany as well, especially because the interests of the real estate industry are dominating the building sector; a good architectural critic is needed as an expert, locally connected, knowledgeable about the building, and analyzing it in a larger context. The architectural critic of today sees criticism as a propaedeutic tool for architectural theory by using the internet as a modern form of communication, and by aiming increasingly at the layperson.

At the same time, instruments for energy performance evaluation, and most recently, assessment systems of sustainable building are evolving such as the DGNB or the BNB certificate. They rarely focus on architectural quality, but guarantee a high level of building technology. Therefore, on one hand these certificates risk being abused by the real estate industry for marketing purposes, but on the other hand they provide the prospect of monitoring the building performance throughout the building life-cycle including occupancy. Thus, the modern architectural critic becomes an ally in an increasing number of participatory planning and evaluation processes. Active and direct participation of educated laypeople is on the political agenda in Germany right now, and it is needed in all phases of the building life-cycle: citizens may get involved as knowledgeable experts of the location in the planning process, or employees may take part as experts for needs and requirements during architectural programming and design review. Finally, occupants may participate as experts of building-in-use in POEs. Therefore, building performance evaluation is a forward-looking complement to modern architectural criticism as it sensitizes people to having an influence on their built environment and to achieving good building performance.

References

Arnulf, A. (2004) Architektur- und Kunstbeschreibungen von der Antike bis zum 16. Jahrhundert. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag.

Baus, U. (2012a) “Wie wir über Architektur streiten.” http://news-world-architects.com/de_09_12_onlinemagazin_gegensaetze_de.html [accessed December 27, 2013].

Baus, U. (2012b) “Pluralismus – Chancen für eine zeitgemäße Architekturkritik.” http://www.german-architects.com/pages/48_12_pluralismus [accessed December 27, 2013].

Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS) (ed.) (2012) Handbuch für eine gute Bürgerbeteiligung: Planung von Großvorhaben im Verkehrssektor. Berlin. http://www.bmvbs.de/SharedDocs/DE/Anlage/VerkehrUndMobilitaet/handbuch-buergerbeteiligung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile [accessed December 27, 2013].

Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS) (2013a) BNB Büro- und Verwaltungsgebäude – Nutzen und Betreiben – Steckbriefe (Version 2012): 3.1.9 Tatsächliche Nutzerzufriedenheit und 5.1.3 Nutzerzufriedenheitsmanagement. http://www.nachhaltigesbauen.de/bewertungssystem-nachhaltiges-bauen-fuer-bundesgebaeude-bnb/bnb-nutzen-und-betreiben.html [accessed December 27, 2013].

Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung (BMVBS) (ed.) (2013b) Leitfaden Nachhaltiges Bauen. Berlin: Conrad. http://www.nachhaltigesbauen.de/leitfaeden-und-arbeitshilfen-veroeffentlichungen/leitfaden-nachhaltiges-bauen-2013.html [accessed December 27, 2013].

Ciré, A. and H. Ochs (eds) (1991) Die Zeitschrift als Manifest. Aufsätze zu architektonischen Strömungen im 20. Jahrhundert. Basel/Berlin/Boston: Birkhäuser.

Colquhoun, A. (1985) Essays in Architectural Criticism: Modern Architecture and Historical Change. Boston: MIT Press.

Conrads, U., E. Führ, and C. Gänshirt (eds) (2003) Zur Sprache bringen. Kritik der Architekturkritik. Münster: Waxmann.

Dechau, W. (1998) Mit spitzem Stift. Architektur in der deutschen Tagespresse. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

European Commission (2013) Energy Efficiency Directive. http://ec.europa.eu/energy/efficiency/eed/eed_en.htm [accessed December 27, 2013].

Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development (2011) Assessment System for Sustainable Building: Administration Buildings. Berlin. http://nachhaltigesbauen.de/fileadmin/pdf/Sustainable_Building/Assessment_System_Sustainable_Building1.pdf [accessed December 27, 2013].

Flagge, I. (1997) Streiten für die menschliche Stadt: Texte zur Architekturkritik. Hamburg: Junius.

Frielinghaus, M. (2013) “Der Bürger als Experte: Einfluss von Bürgerbeteiligung auf Architektur und Baukultur.” In Zentraler Immobilienausschuss (ZIA) (ed.), Bürgerbeteiligung in der Projektentwicklung. Köln: Immobilien Manager Verlag, pp. 95–100.

Froschauer, E. M. (2009) “An die Leser”. Baukunst darstellen und vermitteln. Berliner Architekturzeitschriften um 1900. Tübingen/Berlin: Wasmuth.

Fuhlrott, R. (1975) Deutschsprachige Architekturzeitschriften. Entstehung und Entwicklung der Fachzeitschriften für Architektur in der Zeit von 1789–1918. Munich: Verlag Dokumentation Saur KG.

Kemp, W. (2009) Architektur analysieren. Eine Einführung in acht Kapiteln. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel.

Meyer, U. (2012) “Wir sind noch ganz am Anfang: Im Gespräch zum nachhaltigen Bauen mit Prof. Matthias Sauerbruch.” greenbuilding 4: 41–44.

Miessen, M. (2012) Albtraum Partizipation. Berlin: Merve.

Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Energie, Industrie, Mittelstand und Handwerk (MWEIMH) (ed.) (2012) Werkzeugkasten Dialog und Beteiligung: Ein Leitfaden zur Öffentlichkeitsbeteiligung. Düsseldorf. http://www.dialog-schafft-zukunft.nrw.de/fileadmin/redaktion/PDF/Werkzeugkasten_Dialog_und_Beteiligung.pdf [accessed December 27, 2013].

Philipp, K. J. (1996) Vom Dilettantismus zur Zensur. Zur Geschichte der Architekturkritik. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt.

Preiser, W. F. E. (1972) “Umweltpsychologie: Plädoyer für eine neue Disziplin.” Umwelt 6: 25–28.

Preiser, W. F. E. and U. Schramm (1997) “Building Performance Evaluation.” In D. Watson, M. J. Crosbie, and J. H. Callender (eds), Time-Saver Standards for Architectural Data. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 233–38.

Rambow, R. and N. Moczek (2001) “Nach dem Spiel ist vor dem Spiel: Gebäudeevaluation und Baukultur.” Deutsches Architektenblatt 3: 24–25.

Ramsauer, P. (2013) “Aktive Mitwirkung erbeten: Für eine neue Kultur der Bürgerbeteiligung.” In Zentraler Immobilienausschuss (ZIA) (ed.), Bürgerbeteiligung in der Projektentwicklung. Köln: Immobilien Manager Verlag, pp. 10–12.

Schnell, D. (2005) Bleiben wir sachlich: Deutschschweizer Architekturdiskurs 1919–1939 im Spiegel der Fachzeitschriften. Basel: Schwabe.

Schuemer, R. (1998) “Nutzungsorientierte Evaluation gebauter Umwelten.” In F. Dieckmann, A. Flade, R. Schuemer, G. Ströhlein, and R. Walden (eds), Psychologie und gebaute Umwelt: Konzepte, Methoden, Anwendungsbeispiele. Darmstadt: Institut Wohnen und Umwelt, pp. 153–73.

Further reading

Baus, U. (2009) “Wissen und Präsenz in den Medien: Die neue mediale Öffentlichkeit.” http://german-architects.com, 47/2009 [accessed December 2009].

Baus, U. (2012) “Architektur und Literatur.” In AIT Sonderheft Faces of Interiors 2012, pp. 4–9.

Baus, U. (2013a) “Fragen zur Architekturkritik: Kritik der Kritik XII.” BDA Informationen 1: 32–37.

Baus, U. (2013b) “Welche Architekturkritik brauchen wir heute?” Baumeister 3: 80–81.