ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM AND RADICALISM IN BRAZIL

Introduction

Architectural criticism in Brazil has been deeply rooted in the quest for cultural identity as well as in the various responses to the calls for development and emancipating causes. Since the mid-twentieth century, many Brazilian critics have raised radical agendas to understand the emergence, decline, or persistence of architectural modernism in view of modernization. In the 1950s Mario Pedrosa and in the 1970s Sergio Ferro were two important exponents of a radical strand in contemporary architectural criticism in Brazil. Advancing the limits of revolutionary discourse, each in their own way, they seem to have extracted from the dramatic local experience some productive results for the re-evaluation of architecture, modernity, and criticism.

Background

In 1957, while Brasilia was being built, architect Silvio de Vasconcelos (1916–79) published an article entitled “Art and Architectural Criticism” in the magazine AD Arquitetura e Decoração. The lack of a critical approach to architecture in Brazil concerned him. Such lack derived from several sources, including the autodidactic origins of local architectural critics, their perplexity in the face of a sudden burst of modern architecture in Brazil, and their immediate affiliation to its strong demands for legitimacy. For Vasconcelos, a certain consensus among critics and practitioners seemed to have been achieved, but in such a narrow way that “any unbiased or dispassionate analysis, any attempt to specify bright or less favorable results, became reckless, an offense, a position against art itself, a proof of mental or emotional disability” (Vasconcelos 1957). This attitude had supposedly played an important role in the early rejection of both architectural styles and harsh functionalism. But it was time then – he thought – to move away from such a dogmatic viewpoint, which deprived Brazilian contemporary architecture of a more thorough examination. Criticism should neither mean self-justification, nor limit itself to merely visual kinds of appreciation. To Vasconcelos, architecture was not merely concerned with visible aspects but with experiences and spatial organizations that enhance lifestyles.

The 1950s also coincided with the first substantial restrictions to Brazilian architectural formalism, initially affecting local self-esteem, and eventually stimulating new responses. In Rio de Janeiro, which emerged as the epicenter of Brazil’s modern architecture, such attitudes reflected a relative intellectual and institutional drive for rationalization, following the critique launched in 1953 by Max Bill against its baroque and frivolous aspects (Nobre 2008). In São Paulo, a number of periodicals – like AD itself, which espoused Concrete Art after 1955; Habitat, directed from 1950 to 1954 by Lina Bo and Pietro Maria Bardi; and Acrópole, which increasingly assumed a local avant-garde slant on techno-social discourses – took a rather different perspective on the national debate, later christened São Paulo’s School of Brutalism (Zein 2005; Junqueira 2009; Dedecca 2012). Even Oscar Niemeyer, who in 1958 acknowledged his skepticism about the social role of architecture, admitted “to have taken to adopt an excessive tendency for originality” in many of his early projects despite the sense of economy and logic they required (Niemeyer 1958), a position which, in spite of his own will, would tend to stimulate self-critical attitudes among younger generations.

A critical bias

In spite of Vasconcelos’s evaluation (1957), and an undeniable hegemony of pro-modern and national representations, it does seem that a new critical milieu was emerging in the country by that time. And it was neither always unbiased, nor dispassionate. It was partly composed of an early generation of professional art critics, such as Mario Pedrosa (1900–81), Geraldo Ferraz (1905–79), Mario Barata (1921–2007), and Flavio Motta (1923–), attracted to the architectural debate, which had acquired recent importance in the Brazilian cultural landscape. In other parts, it was formed by practitioners, of whom some were strongly rooted in the field as major players such as Lucio Costa (1902–98), Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012), Lina Bo Bardi (1914–92), and João Vilanova Artigas (1915–85); others were younger or less renowned architects, who had shifted into more specialized careers as architectural theorists, historians, or preservationists, like Vasconcelos himself, Edgar Graeff (1921–90), Carlos Lemos (1925–), and Sergio Ferro (1938–).

To review the entire history of architectural criticism in Brazil would be an impossible task in this chapter. Its various theoretical foundations and diverse poetic, cultural, and political agendas, the productive networks, and the unique individual itineraries it relied upon are multifaceted. My objective, through an outline of a couple of exemplary individual perspectives, is simply to address a certain bias which seems to have played a creative role in Brazilian architectural criticism throughout the twentieth century: its trend toward radicalism. I hope that reconnecting some local critical challenges to Brazil’s modern architecture debate from the 1950s onwards may help illuminate a few new ways to address the international contemporary milieu of architectural criticism.

By a radical bias I refer to a general set of ideas and attitudes that reject the conservative mentality and political behavior prevailing in Brazil. Such radicalism would eventually shape a peculiar tradition, intensely responsive to the pressing socio-cultural problems and their corresponding aesthetic dilemmas, tending to view them as a whole at the scale of the nation or even at a larger global scale of modernity. Strongly rooted in the urban enlightened middle classes, this radical tradition in criticism has often endeavored to identify with the issues raised by the working class, and at times has assumed a revolutionary stance. But if the radical critic is mainly an insurgent, and “his thought can advance to really transformative levels, it may also retreat to conservative ones” (Candido 1995). For it is usually aimed at feasible changes in the underdeveloped Brazilian society, which is full of oligarchic remains and has often experienced military interference. It is important to highlight this touch of ambiguity that permeates the radical sense of commitment because it is potentially open to accommodating contradicting narratives in Brazil.

Abstraction and revolution

In his article, Silvio de Vasconcelos refers to Mario Pedrosa’s approach to the topic of architectural criticism. Different from Vasconcelos, though, Pedrosa – as an art critic – had reiterated his dislike for functionalism in architecture, praising the maverick virtues of Brazilian modern architects who had “sent the functional diet to hell.” For Pedrosa, it was time to overcome the established “narrow kind of architectural criticism” in order to reach “its specific task, which is aesthetic appreciation” (Pedrosa 1957a).

Since 1944, when Pedrosa published his first articles on Alexander Calder’s (1898–1976) solo retrospective held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) the year before, he had embarked on a radical path toward abstract art and aesthetic criticism (Pedrosa 1944). From then on, the main issues of the period began to emerge in his writings: the autonomy of art, relations between art and technology and art and utopia, links between visuality and perception, debates on abstraction versus realism, integration or synthesis of the arts, etc. It is telling that he started his career as a critic in 1933 with an essay on “Käthe Kollwitz and the Social Tendencies in Art,” where he proposed a kind of “proletarian art” able to convert the emotional and collective life of the proletariat into a subject of visual perception (Pedrosa 1933).

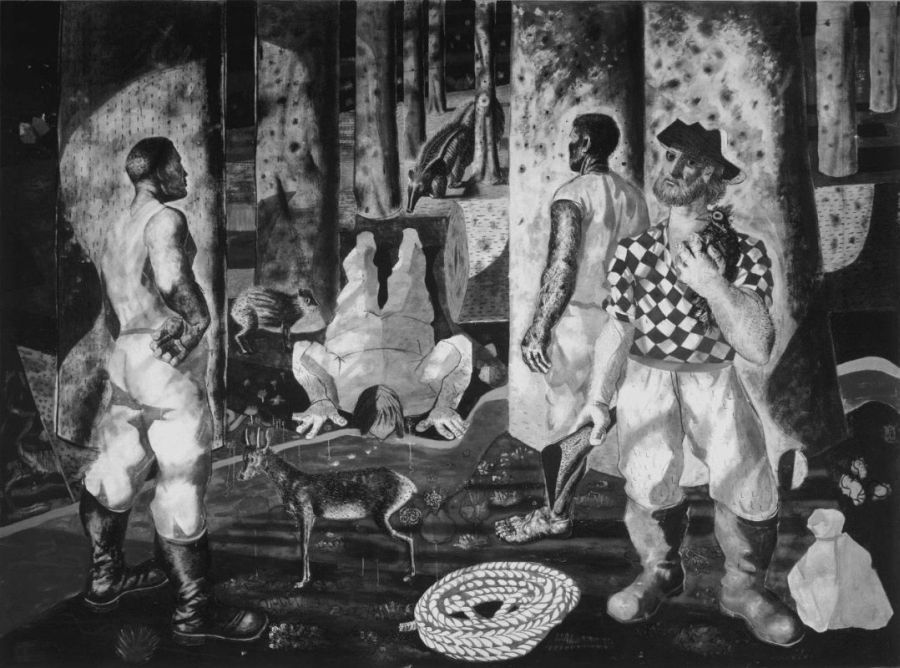

Indeed, Pedrosa’s prolific collaboration in several newspapers throughout his life wavered between art and politics. In 1942, in the face of Candido Portinari’s (1903–62) murals for the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, recently painted with themes drawn from Brazilian history, Pedrosa disregarded their gravely nationalist representations. Absorbed in a sophisticated visual analysis of the series, he advocated for aesthetic categories of judgment in clear reaction to the approach of Socialist Realism (Pedrosa 1947). “Through processes immune to any recipe, he [Portinari] tends to what one might call de-mythologizing of icons, images and landscapes. Evading external contingencies of time and place, national or not, he multiplies the geometric signals in a sort of anxiety for abstraction” (Pedrosa 1943) (Figures 5.1 and 5.2).

Aesthetic value and social commitment could thus be reconciled “in the field of artistic ‘procedures’” (Arantes 1991). The problems then posed to the concept of art by Calder also seemed to respond to his specific platform on abstraction: the idea of the unfinished work, the issues of suspension, surprise, and of spatial stimuli, the problems of organizing movement and contrast, of variable relations of forms in space. “Disembodied of any convention or external function,” Calder’s works avoided any realistic suggestion (Pedrosa 1944). Nevertheless they were intimately integrated into collective life. Their prosaic character did not avoid the direct contact of the people, supposed to move, touch, and push the artist’s Estabiles and Mobiles. They occupied public squares and gardens with “unseen things, of suggested worlds and unknown animals, of new fables, dreams, and imaginations, of reanimating silences.” They evoked “motifs of remote geological eras or omens of things yet to exist” in such a way that one could label it “a democratic art because it can be made of anything, fit anywhere, in the service of any condition, noble, rare or unusual,” for it revitalized and transformed “the everyday lives and the sad environment in which the large brutalized masses vegetate” (Pedrosa 1944).

FIGURE 5.1 Candido Portinari, Desbravamento da Mata (Entry Into the Forest), mural painting, 316 × 431 cm, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 1941

Source: Projeto Portinari.

As such, revolutionary art could never be seen as cultural nutrition to sustain a mass revolution. Its function was not to compete with mass communications, but to specify and isolate unperceived angles of an ever-changing visual realm. It was therefore only a path to a “revolution in sensibility” (Pedrosa 1952). The role of the critic would then be to question if an architectural work embodied certain aesthetic impulses (Pedrosa 1957b), or else “to simply and immediately perceive architecture as such” (Pedrosa 1957c). To do so, the radical critic could not avoid being “partial, passionate nor political.” In a Baudelairian way, he should search for a point of view that opened up more horizons (Pedrosa 1957d).

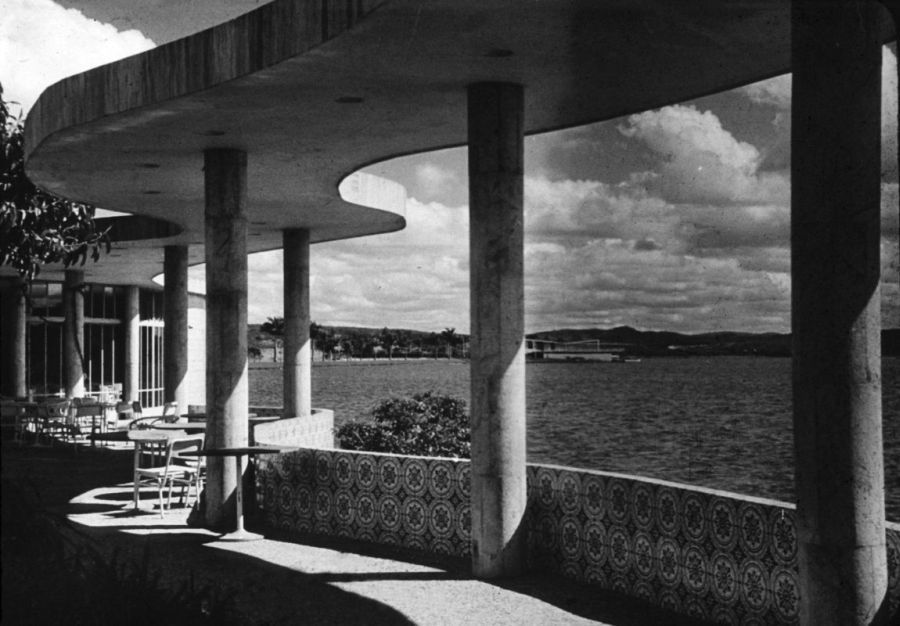

By the 1950s Pedrosa had definitely reached one of the most active and influential positions in the Brazilian art world, heading important art movements, lecturing and publishing intensely, spreading established and supporting emerging art theories, counseling young artists, curating some of the most remarkable exhibitions of the time, and becoming a leading name in the International Association of Art Critics in Brazil (Arantes 1995). In a lecture given in Paris in 1953 he addressed the overall modern architectural production in Brazil. Highlighting the “revolutionary state of mind,” Pedrosa related its militant dogmatism to the belief in the democratic virtues of mass production. As for Brazilian architecture, “the new builders” seemed to rely too much “upon the power of dictators to implement their ideas.” It had of course remarkable aesthetic qualities: the inventive design of the brise-soleil, for instance, controlling light and heat as well as animating façades through pictorial and graphic effects; the lightness of structural solutions and unusual combination of materials; the imaginative articulation of surfaces, volumes, and spaces; the integration of interior space, the outdoors, and the landscape; the games of free forms, even at the expense of the program; and its new sense of monumentality (Figures 5.3 and 5.4). Nevertheless there was a clear contradiction between its social ideals and the concerns for power representation and self-promotion. Its luxurious forms precisely derived from such original trade with dictatorship (Pedrosa 1953). Like an “island” or an “oasis” in the vastness of the country, they reinforced the gap between intentions and potentialities in modern architecture in Brazil.

FIGURE 5.2 Candido Portinari, Descoberta do Ouro (Discovery of Gold), mural painting, 394 × 463 cm, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA, 1941

Source: Projeto Portinari.

FIGURE 5.3 Oscar Niemeyer, Dance Hall in Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1940–1943

Source: photo by Gustabo Neves da Rocha Filho. FAU-USP’s Library. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/deed.pt_BR

FIGURE 5.4 Oscar Niemeyer, Casino in Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1940–1943

Source: photo by Eduardo Kneese de Mello. FAU-USP’s Library. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/deed.pt_BR

from the top of this platform the regional will be subsumed in the national, the national in the international, and the nation’s inequalities will be dismantled. A new Brazil will have its own messages, its own voices, its own modes, and its own art as well, all perfectly intelligible to any other messages within the semiological system of global communication.

(Pedrosa 1973)

By 1973, when this last article was published, the city had been taken over by the military regime and Pedrosa was living in Chile as a political exile, accused by the Brazilian government of having vilified the nation.

Material work and liberation

By the end of the 1950s, Sergio Ferro was studying architecture at the University of São Paulo. In 1963, he co-authored with his colleague Rodrigo Lefèvre an article called “Initial Proposal for a Debate: Possibilities for Action.” The title manifests a critical approach to practice, emerging from the dilemmas posed to architecture in an underdeveloped country, which was booming economically since the end of World War II, and which had recently inaugurated its new capital. For them, any architectural action in Brazil inevitably faced a “situation in conflict” between the expansion of productive forces and the vital needs of the people. In spite of aesthetic or technical qualities achieved by any work of architecture, major contradictions were constantly undermining its social relevance. As such, any contemporary achievement in design work should always be evaluated in light of the larger processes of production, the division of labor, alienation, and commodification within the building process (Ferro and Lefèvre 1963). The established idea of architecture as a luxury item, and of criticism as a kind of evaluation foreign to the real needs of producers and consumers, expressed the degree of gentrification to which the professional practice had surrendered (Ferro et al. 1965).

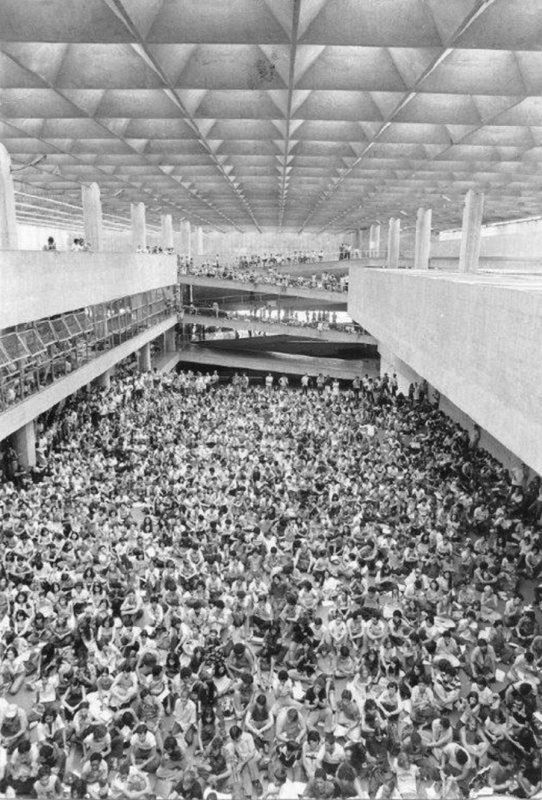

Sergio Ferro belongs to a generation of architects created by the critique of Brasilia and of its corresponding development ideology, which would lead him to a break with modern architecture. This break in Brazil was particularly clear within the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo (FAU-USP) by the end of the 1960s and staged through the confrontation over the relationship between architectural practice and social change (Arantes 2002; Koury 2003; Williams 2009). On one hand, there was architect and professor Vilanova Artigas, one of the main leaders of modern architecture in Brazil, leading the immediately preceding generation at FAU. He advocated for the ability of a professional elite to deliver revolutionary solutions, and posited the need to see design as a compromise between intentions and means (Artigas 1967). On the other hand were his young disciples Ferro, Lefèvre, and Flávio Império, who belonged to the so-called Nova Arquitetura group, and who had just begun to teach at the school. Disregarding professional niceties at a moment when Brazil had been taken over by a military regime, they criticized the prevailing commitment of architecture to a conservative kind of modernization in Brazil. According to Ferro, this commitment had clear impacts on the processes of construction. The despotic command of design intensified the huge complex of forces that seemed to increasingly submit millions of workers to exploitation and inefficiency on the building sites (Ferro 1967) (Figures 5.5, 5.6, 5.7).

FIGURE 5.5 João Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1961–1969

Source: SEF-USP.

This general hypothesis about the break between design and building referred to the entire history of visual perspective from its invention in the Renaissance to its applications in the first machine age. But Ferro’s approach would lead to the critique of Brazilian contemporary architecture as well as his own group’s work:

The new architects, raised within this tradition (of Niemeyer and Artigas) to which the primary concern was the large collective needs, have been feeling, approximately since 1960, a widening gap between their broad training and expectations, and the narrowness of their professional tasks. … Hence this kind of hillbilly Brutalism (as opposed to the aestheticist European Brutalism), its forced “didactization” of construction procedures, its excessive constructive rationalization, its “economism” which generates ultra-dense spaces, [is] rarely justified by objective requirements, etc.

(Ferro 1967)

FIGURE 5.6 João Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1961–1969

Source: photo by Raul Garcez. FAU-USP’s Library.

Such an approach owed a lot to a wider Brazilian and Latin American debate on development and underdevelopment, seen as part of an uneven development of world capitalism, which inspired many artists and intellectuals of the period to take sides with the working classes (Arantes 2004). Ferro would interpret that tendency by shifting the focus of architectural analysis from design achievements to the “relations of production” in the building realm. Critical work should thus focus on the huge gap between the local “mannerist elite of architects,” aesthetically updated and liberating, and the gigantic unskilled workforce, crushed by some of the most violent conditions of production and excluded from all the benefits of modernization.

FIGURE 5.7 João Vilanova Artigas and Carlos Cascaldi, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1961–1969

Source: photo by Eduardo Kneese de Mello. FAU-USP’s Library. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.pt_BR

In 1976, Ferro started to publish parts of the book that soon would turn him into one of the most pervasive – and inconvenient – Brazilian architectural theorists. O Canteiro e o Desenho (The Building Site and Design), first published as a book in 1979, is not an account of Brazilian architecture. Drawing from Marx’s theory of “fetishism” (Marx 1995), the author refers to modernity at large to grapple with the manufacturing condition of the architectural object and the schism between thinking and making, duty and power. He refers to the impact of a book edited a few years prior by Andre Gorz, The Critique of the Division of Labor, as a pathway to the study of “commodity’s fetishism,” forgetfulness and foreclosure (Ferro 2011). “If design sets itself as an instant mobile of production, and if it prints in it its symbolic script, it is because it materializes separation and reifies disruption” (Ferro 1977). It is thus

an indispensable tool for despotic direction. To speak about design, as we know it now, connotes dependence and despotism. Because it was made what it is through the separation of reason from concretion, and through the violent disruption of production. … Design is thus one of the embodiments of the heteronomy of the building site. It is an obligatory path for the extraction of surplus value and cannot be separated from any other kind of drawing for production.

(Ferro 1982)

There was no other way to decipher the farce of architecture except by referring to its material making and to its role on the production of space as “exchange value.”

The book was published while Ferro was in France, where he was sent into exile for having joined the armed resistance to dictatorship. Indeed, in 1973 he joined the architecture school at the University of Grenoble, founding an experimental laboratory around the concept of a “constructive idea” (Ferro 1994). In a work published much later, the author clarifies his own methodological alternative. For him, architecture was always marked by the complexities and tensions within its production and should be seen as a whole, involving material investment, architectural schemes and projects, execution, reception, use, and management. Any analysis of a piece of architecture should thus not focus on the object alone, but on its constructive genesis within the realm of a political economy (Ferro 1996).

More recently Ferro has reconnected to the Brazilian architectural milieu, where many of his ideas have been either received enthusiastically or harshly refused. For some, Ferro’s focus on the basic contradictions of work relations has had a paralyzing effect on design practice. For others, as a practitioner, he has been understood as a source of experimental architecture, while, as a critical theorist, he could be seen as having paved the way to new readings of architecture able to deny the oppressive tendencies of modern production.

Conclusion

No questions remain about the persistence of radical representations in Brazil, still now rather potent in the regional architectural system, as well as operative in architect’s collective memory, imagery, and aspirations. They have varied in terms of objects, categories, strategies, and discourses, and eventually surrendered to the limits of their own historical material and theoretical choices. It is interesting, though, to realize how much this radical bias has contributed to the understanding of modern architecture as a global force.

Both Mario Pedrosa and Sergio Ferro were strongly influenced by their local backgrounds and had to deal with contemporary economic, political, and ideological dilemmas in Brazil: cultural closure and creativity, modernization and authoritarianism, development and underdevelopment. But in light of the discipline, their approaches to architecture seem the most innovative and refreshing. Indeed, their connection to the international states of mind concerning criticism and design has often been forgotten. In Pedrosa’s case: the fatigue with functionalism, the appeal to new kinds of monumentality and publicity, the concept of modernity as an unfinished, movable, and always surprising project. In Ferro’s case: the contemporary investigation of critical, reflexive, theoretical, empirical, communitarian, or non-designed architecture.

In fact, Pedrosa’s insistence on the aesthetic power and public relevance of architecture, and Ferro’s obsession with the material relations in which architecture is inevitably engaged, seem to have illuminated areas usually neglected by the majority of contemporary architectural criticism. Their approaches thus are relevant for the understanding of architectural production not only in a developing country like Brazil, but anywhere where art and labor have developed in modern terms. This cosmopolitan output from a locally grounded perspective, despite its specific contingencies and obstacles, is possibly where a great contribution to the expansion of critical horizons in architecture may still be found.

References

Arantes, O. B. F. (1991) Mário Pedrosa: itinerário crítico. São Paulo: Editora Página Aberta.

Arantes, O. B. F. (1995) “Dados biográficos (cronologia).” In M. Pedrosa, Política das artes. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, pp. 349–63.

Arantes, P. F. (2002) Arquitetura Nova: Sérgio Ferro, Flávio Império e Rodrigo Lefèvre, de Artigas aos mutirões. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Artigas, J. B. V. (1967) “O Desenho.” In Artigas, Caminhos da Arquitetura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2004, pp. 108–18.

Bruand, Y. (1971) “L’Architecture contemporaine au Brésil.” Paris: Université Paris IV (PhD dissertation).

Candido, A. (1995) “Radicalismos.” In Candido, Vários Escritos. São Paulo: Duas Cidades.

Cappello, M. B. C. (2006) “Arquitetura em Revista: arquitetura moderna no Brasil e sua recepção nas revistas francesas, inglesas e italianas (1945–1960).” São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo (PhD thesis).

Costa, L. (1952) Arquitetura Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Saúde.

Dedecca, P. G. (2012) “Sociabilidade, Crítica e Posição: o meio arquitetônico, as revistas especializadas e o debate do moderno em São Paulo (1945–1965).” São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo (Master’s dissertation).

Ferro, S. (1967) “Arquitetura nova.” In Ferro, Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006, pp. 47–58.

Ferro, S. (1977) “II – O Desenho.” Almanaque 3: 74–101.

Ferro, S. (1982) O Canteiro e o Desenho, 2nd edn. São Paulo: Projeto.

Ferro, S. (1994) “Programa para polo de ensino, pesquisa e experimentação da construção.” In Ferro, Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006, pp. 222–32.

Ferro, S. (1996) “Questões de método.” In Ferro, Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006, pp. 233–40.

Ferro, S. (2010) A história da arquitetura vista do canteiro: três aulas de Sérgio Ferro. São Paulo, FAU-USP.

Ferro, S. (2011) “História da arquitetura e projeto da história, entrevista a Felipe Contier.” Designio 11–12: 113–26.

Ferro, S. and R. Lefèvre (1963) “Proposta inicial para um debate: possibilidades de atuação.” In Ferro, Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006, pp. 33–36.

Ferro, S., R. Lefèvre, and F. Império (1965) “Arquitetura experimental.” In Ferro, Arquitetura e trabalho livre. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006, pp. 37–44.

Forty, A. and E. Andreolli (eds) (2004) Brazil’s Modern Architecture. London: Phaidon.

Goodwin, P. (1943) Brazil Builds: Architecture New and Old, 1652–1942. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Junqueira, M. (2009) “Poéticas da razão e construção: conversa de paulista.” São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo (PhD dissertation).

Koury, A. P. (2003) Grupo Arquitetura Nova: Flávio Império, Rodrigo Lefèvre e Sergio Ferro. São Paulo: Romano Guerra/EDUSP/FAPESP.

Lemos, C. (1979) Arquitetura Brasileira. São Paulo: Melhoramentos/EDUSP.

Liernur, J. F. (1999) “The South American Way.” Block 4: 23–41.

Martins, C. A. F. (1999) “Hay algo de irracional …” Block 4: 8–22.

Marx, K. (1995) “Commodities.” In Marx, Capital: A Critique of political Economy. Volume I, Book I, Part I. Marx/Engels Internet Archive.

Mindlin, H. (1956) Modern Architecture in Brazil. Rio de Janeiro/Amsterdam: Colibri.

Niemeyer, O. (1958) “Depoimento.” Módulo 9: 3–6.

Nobre, A. L. (2008) “Fios Cortantes: projeto e produto, arquitetura e design no Rio de Janeiro (1950–1970).” Rio de Janeiro: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro (PhD dissertation).

Pedrosa, M. (1933) “As tendências sociais da arte e Käthe Kollwitz.” In Pedrosa, Política das artes: textos escolhidos I. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1995, pp. 35–56.

Pedrosa, M. (1943) “Portinari: de Brodósqui aos murais de Washington.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 7–25.

Pedrosa, M. (1944) “Calder, escultor de cata-ventos.” In Pedrosa, Modernidade cá e lá: textos escolhidos IV. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2000, pp. 51–66.

Pedrosa, M. (1952) “Arte e revolução.” In Pedrosa, Política das artes: textos escolhidos I. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1995 pp. 95–98.

Pedrosa, M. (1953) “A arquitetura moderna no Brasil.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 255–64.

Pedrosa, M. (1957a) “Arquitetura e crítica de arte I.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 269–71.

Pedrosa, M. (1957b) “A critica de arte na arquitetura.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 273–75.

Pedrosa, M. (1957c) “Arquitetura e crítica de arte II.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 277–79.

Pedrosa, M. (1957d) “O ponto de vista do critico.” In Pedrosa, Política das artes: textos escolhidos I. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1995, pp. 161–64.

Pedrosa, M. (1957) “Reflexões em torno da nova capital.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 303–16.

Pedrosa, M. (1958) “Utopia – obra de arte.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 317–19.

Pedrosa, M. (1959) “Introdução à arquitetura brasileira II.” In Pedrosa, Dos Murais de Portinari aos Espaços de Brasília. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981, pp. 329–35.

Pedrosa, M. (1973) “A bienal de cá para lá.” In Pedrosa, Política das artes: textos escolhidos I. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1995, pp. 217–84.

Santos, P. (1977) Quatro Séculos de Arquitetura. Rio de Janeiro: Valença.

Tinem, N. (2006) O Alvo do Olhar Estrangeiro: o Brasil na historiografia da arquitetura moderna, ed. João Pessoa. Universidade Federal da Paraíba.

Vasconcelos, S. de (1957) “Critica de arte e arquitetura.” AD Arquitetura e Decoração 24.

Williams, R. J. (2009) Brazil (Modern Architectures in History). London: Reaktion Books.

Zein, R. V. (2005) “A arquitetura da escola paulista brutalista 1953–1973.” Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (PhD dissertation).