ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM MEETS BUILDING EVALUATION IN JAPAN

Introduction

Hospital buildings have not received a great deal of attention in architectural critique in Japan. This may be because the intense focus on the provision of medical functions made hospital buildings just monotonous. However, a hospital requires comprehensive environment development and the realization of a restorative environment. This chapter will discuss the general trend seen in the articles of Shin Kenchiku, Japan Architects, and AIJ Work Selections and will clarify the unique designs in a number of hospital buildings. The first case study is a large-scale and multi-function development resembling a townscape. Tokyo Metropolitan Fuchu Medical Plaza with 1,350 beds has a variety of functions and is serviced by a full spectrum of facility management. The second is a healing environment in Aichi Children’s Health and Medical Center, which was presented in a British architectural magazine, Hospital Development, in 2008. The third is the design of a dilettantish and unique approach by Atelier Architects, Katta Public General Hospital.

Key issues in hospital architecture critique

British building appraisal tradition

Becker (1990) acknowledged British building appraisal to be a tradition of balanced evaluation of building performance. The impressive book we remember is Stone’s British Hospital and Health-Care Buildings, Designs and Appraisals (1980) where British hospitals were introduced by “Architect’s account” and evaluated in “Appraisal” by another expert. Stone’s book (1980) consisted of articles originally published in The Architects’ Journal mostly in the 1970s. This approach has been adopted widely around the world. In Japanese architectural journalism, Shin Kenchiku, the most widely read architectural magazine in Japan (with its English translation issues as Japan Architects), presents monthly critique in its series of issues. The articles of AIJ Work Selections have been published annually by the Architectural Institute of Japan since 1989. They consist of introductions by the architect, and appraisals by other experts. However, one shortcoming is that hospital architecture is not discussed in detail. Lastly, it should be noted that the Journal of Japan Institute of Healthcare Architecture was first issued in 1968, and has reported on newly built health care facilities with explanatory photographs and drawings, including articles and research papers. The authors played responsible roles in the design of hospitals which were published in the journal and one hospital received the first Healthcare Architecture Award by the Institute in 1991. Although a review of planning and design features of awarded hospitals would suit the purpose of this chapter, the authors have decided to keep that task for another occasion.

Hospital as a city

Northwick Park Hospital and Clinical Research Center, designed by John Weeks of Llewelyn-Davies Weeks, is the first deliberate attempt to design a modern hospital with no finite form (Stone 1980). In this project the architects showed a piecemeal growth of the hospital complex as a “village.” This was introduced in Japan by Professor Yasushi Nagasawa and became a strong supporting argument to provide for future growth by clarifying the main circulation corridor in a hospital complex as a “hospital street” as in a village main street.

Fuchu Medical Plaza was introduced in Shin Kenchiku (July 2010 edition). It is certainly one of the largest hospitals in Japan with a total of 1,350 beds. It is a complex of two hospitals, namely Tokyo Metropolitan Tama General Medical Center and Tokyo Metropolitan Pediatric General Medical Center. The development and operation program has been carried out as a private finance initiative (PFI) of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. The average number of facility users totals over 6,000 persons per day, including staff and over 2,000 outpatients. Having outpatients of this magnitude in a hospital may be considered a significant speciality in Japanese hospitals.

An article of interviews among architects of hospital projects has appeared in Shin Kenchiku titled “Hospitals in connection to Townhood,” discussing design issues related to users’ comfort, including wayfinding. To a limited extent some works by Professor Roger Ulrich have also been introduced.

Evidence-based design

The authors would like to discuss an article which appeared in the distinguished British architectural magazine, the Architectural Review (Finch 2005a). Paul Finch, who was an Architectural Review author at that time, starts his essay by introducing Professor Roger Ulrich and evidence-based design which showed that certain environments can help patients recover more quickly, using fewer drug treatments. When compared to the US and UK, Professor Ulrich has not yet achieved a strong presence in Japan. It has been pointed out that the above-mentioned drug treatments are seldom used in Japan, so that the validity of research has been questioned. This view is quite strange in the sense that if the treatment is meaningful in a certain society, the issue of quantity is a matter of decision-making. However, when Ulrich’s theory was first introduced in Japan, a certain Doctor S. Haruyama had already published in Japan a book entitled A Great Revolution in the Brain World (1995) which sold a million copies. He proposed a new type of health care facility where nurses wearing kimonos welcomed a patient, based on the principle that “Illness is the result of consciousness,” a Japanese saying. Looking for more construction work in health care, representatives of general contractors and subcontractors crowded into this doctor’s office. However, they found that it was only an empty idea.

FIGURE 17.1 A picture book on the journey of Marron Sister and Acorn Brother

Source: Akikazu Kato.

Healing environment

Japan has a long history of healing environments and healing gardens. The first Buddhist temple established for healing purposes was Yakushiji in Nara. Yakushi means pharmacist. In the year 680 Emperor Temmu commissioned the project to pray for the recovery from illness of his wife, who succeeded him as Empress Jito. The temple was moved to the present site in 710, in coordination with the development of the ancient capital of Heijokyo.

Garden design was much improved in later temples such as the Ginkakuji, Temple of Silver Pavilion, in Kyoto. Shogun Yoshimasa Ashikaga initiated plans to for creating a retirement villa and gardens as early as 1460. It is said that Yoshimasa sat in the pavilion contemplating the calm and beauty of the gardens while the Onin War (1467–77) worsened and Kyoto was burned to the ground. After his death the temple became a Zen temple, Jishoji, named after Yoshimasa’s monk name.

However, the term healing garden may originate in the gardens of the Children’s Hospital at San Diego, in California, USA. “Carley’s Magical Gardens” are filled with bronze animals, giant buggies, and interactive play areas. The design is inspired by little Carley Copley, who was just a toddler when her battle with leukemia came to an end. A picture book was made from Carley’s memories, and her parents funded the project to build gardens to allow Carley’s spirit to live on. Cooper Marcus and Sachs (2013) introduced survey results of healing gardens and pointed out that unexpected uses by patients’ families and staff are also important.

Architects and administrators of a number of children’s hospitals in Japan were inspired by the above design process and one of most impressive examples is Aichi Children’s Health and Medical Center (Figure 17.1). This Center was discussed in the British magazine Hospital Development, in 2008. The Center depicts the story of Marron Sister and Acorn Brother who were born in the Center forest and went on a journey to meet various animal and plant friends. A picture book was made to illustrate various areas of the Center, and pictures and ornaments are presented on hospital walls. Thus, by looking at the website picture book, child patients and their parents can familiarize themselves before the actual hospital visit. This type of embodied presentation by using print characters and environment provides for a better understanding of health care environments.

Rediscovery of the Nightingale Ward

The Nightingale Ward is a typical ward building which is designed and built following a common design concept for health care facilities as advocated by Florence Nightingale in the nineteenth century, and similar designs can be found in various countries around the world. At the beginning of the twenty-first century the design was adapted in hospital architecture designed and built in Japan and the UK.

Katta Public General Hospital, Japan

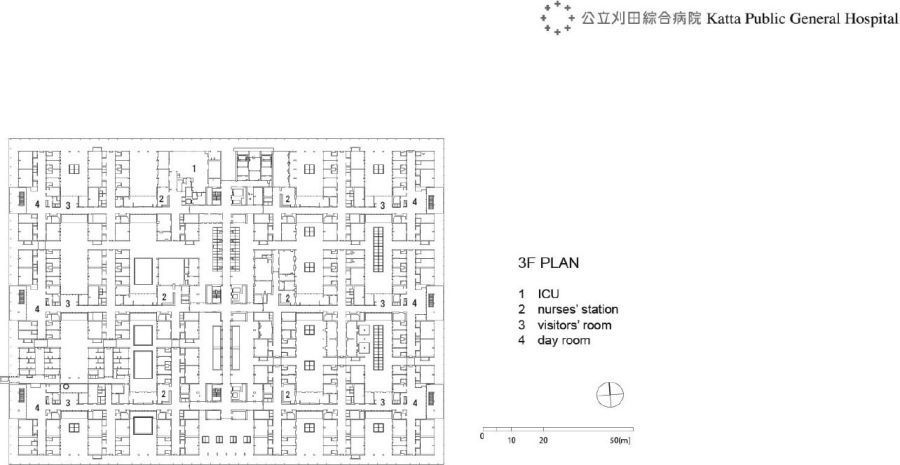

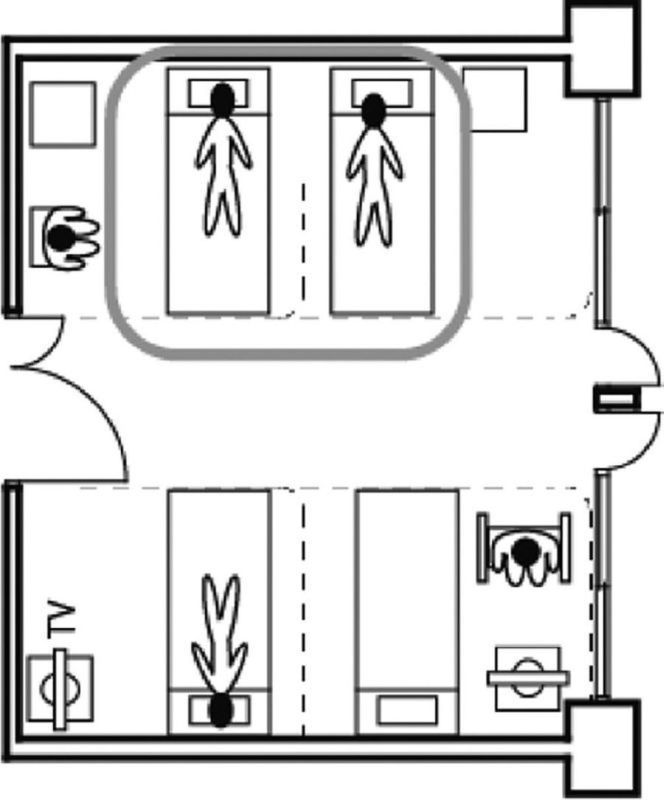

Katta Public General Hospital was presented in the June 2002 issue of Shin Kenchiku magazine. A 308 bed hospital was rebuilt at a new site to create a floor area of 26,164 square meters. This amounts to 85 square meters per bed, and it was designed by three collaborative architects Taro Ashiwara, Ko Kitayama, and Hideto Horiike. Although many specialists for medical services and health care architecture were involved in the design process, these three architects avoided a tower on muffin type of building where high-rise inpatient quarters sit on the footage of a services block, which is a type of building often used in hospitals in urban settings. They instead created a low-rise three-story building, with inpatient wards on the third floor (Figure 17.2). Ashiwara referred to a modern interpretation of a nineteenth-century Nightingale Ward in the magazine interview. We assume that they received advice from Professor Kazumasa Otaki of Yokohama National University at that time. It is interesting that the full Japanese translation of Florence Nightingale’s 1860 classic Notes on Nursing was revised in 2000. The first translation came out in 1974 in the Nightingale Writing Series including Notes on Hospitals. In the floor plan of Katta Hospital, a combination of four-bed rooms and single rooms are used in the ward. Thus, the 30-bed ward in the original Nightingale Ward is no longer being used. However, because the ward wings are all on the third floor they are placed in parallel rows facing 9.3 meter-wide courtyards. This arrangement of ward wings follows the design principle of the pavilion used in Nightingale Hospitals. The interview also refers to the features of Nightingale Wards in relation to airborne cross-infections, which was one of the results of nineteenth-century rational thinking. Katta Hospital was recognized to have realized a good environment in two critiques reported in the following month’s issue of the magazine.

Evelina Children’s Hospital, UK

Evelina Children’s Hospital was presented in the May 2005 issue of the Architectural Review (Finch 2005b). Following the formation of the National Health Service, the institution was incorporated within the trust responsible for St. Thomas’s and Guy’s Hospital, and relocated to the new site next to the 1871 Nightingale Ward complex. The new building houses 140 beds with a floor area of 16,500 square meters, or 118 square meters per bed. The designers, Hopkins Architects, claim on their home page that it was their first health care project, where ideas pioneered in workplace design have been applied. They claim that like offices, hospitals require efficient and flexible layouts, including informal social interaction spaces. Following an introductory article on evidence-based design by Professor Roger Ulrich, Finch (2005) acknowledges the design of Evelina Children’s Hospital as a hospital that doesn’t feel like a hospital. This reflects high aspirations both for an architectural “wow” factor, and for a high level of construction quality. The interior design is of an abstract nature. The ward plan consists of six- and four-bed bays and single rooms. The paired bays are covered by one nursing station and the use of counter-partitions to a snaking corridor results in an open environment of a traditional Nightingale Ward.

FIGURE 17.2 Ward plan of Katta Public General Hospital (floor level 3)

Source: courtesy of Taro Ashihara Architects.

Privacy versus supervision

A comprehensive introduction to Nightingale Ward design is provided by Thompson and Goldin (1975). The authors discuss a transition in American hospitals from the use of multi-bed rooms to single-bed rooms which they describe in detail referring to various building examples, research papers in the US and UK, and surveys carried out in the Yale University Hospital. The American preference for privacy is referred to by one chapter title in the book, “A Loud, Loud Noisee about Privacy: A Review of Contemporary American Literature on the Hospital Room.”

More recently, Padbury et al. (2013) discussed the all single room NICU built at the Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island. The underlying concept is that the physical environment can have profound effects on the recovery of very small infants. In an open multi-bed room they are typically exposed for weeks to invariant lighting, sleep deprivation, and auditory disruption. Thus, the design of the new unit was critical to the effective delivery of developmentally appropriate family-focused care.

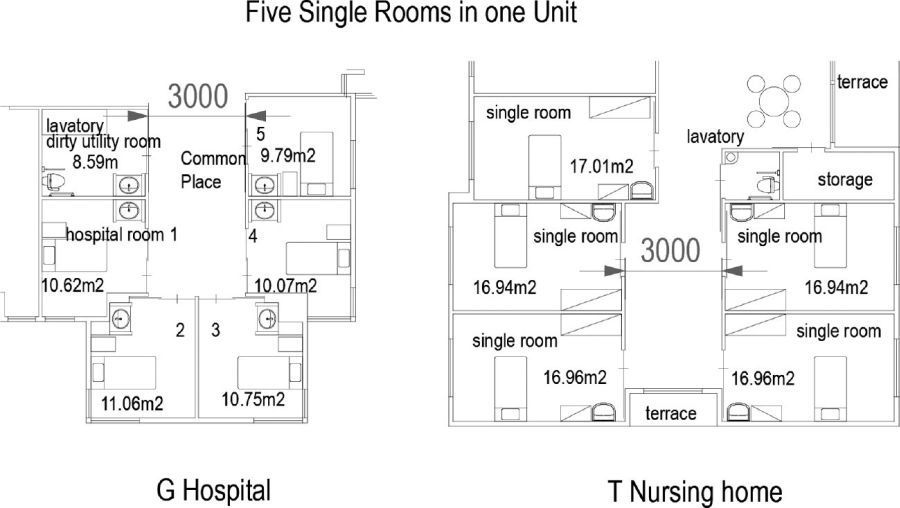

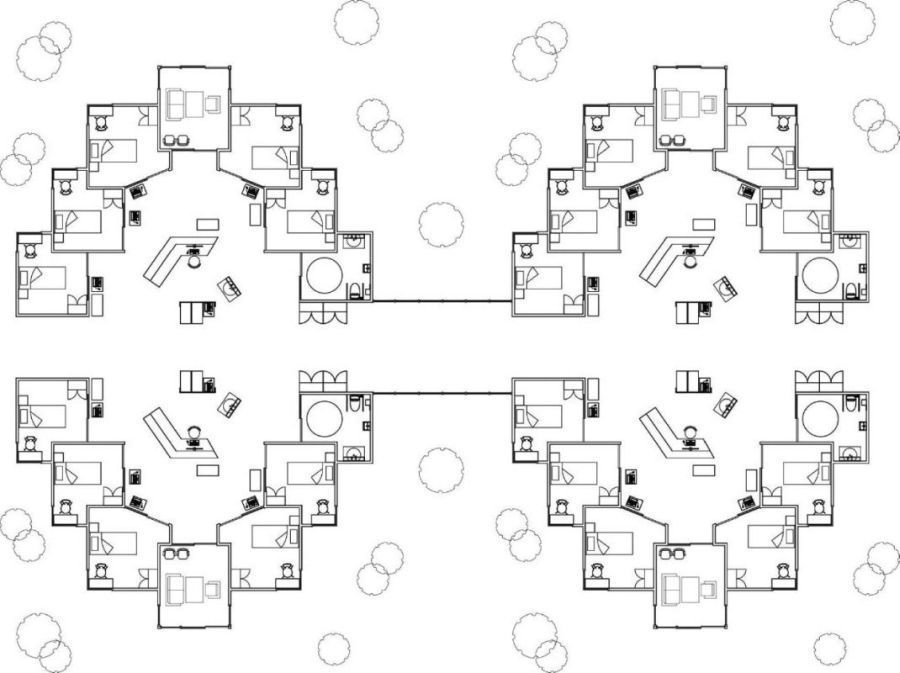

FIGURE 17.3 Single rooms with multi-bed room arrangement

Source: Shiho Mori.

Discussions on hospital bed rooms

Advantages and disadvantages of single-bed and multi-bed rooms

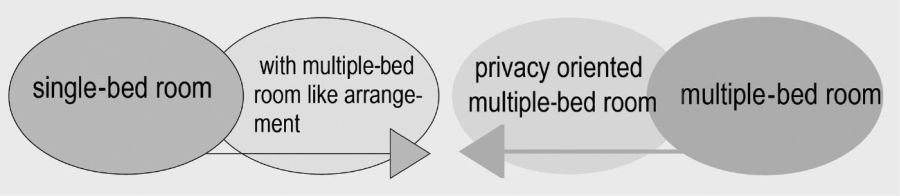

When the advantages of single-bed rooms are compared with those of multi-bed rooms, the former are seen to provide more privacy, while the latter provide for better observation and efficiency in nursing (Figure 17.3).

A variety of recent ward room designs in Japan proposes privacy-oriented multi-bed rooms. In the example at M Hospital, a small window is placed near each bed to provide for better views and air flow, which results in a plan that secures more privacy within a limited floor area. However, the movement area inside the bed room is found to be inadequate and the space between beds is of minimum size.

In a newly proposed Pod Ward Plan, single rooms are arranged like a multi-bed room. Examples are found at G hospital which is under construction and at T Nursing Home. At G Hospital a common space in the center of the pod plan provides for a nurses’ charting station and communication among patients. In T Nursing Home, the floor area for the central common space is realized with a larger area to enhance living facilities for the elderly.

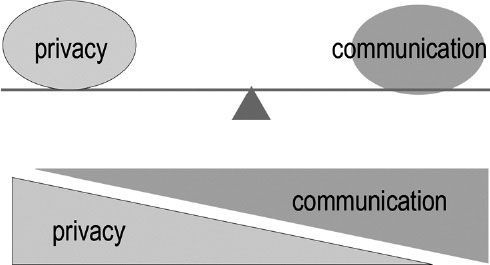

The above two planning and design approaches can result in a better balance between the two issues of privacy versus supervision (Figure 17.4). An ideal healing environment may require a suitable balance between contradictory privacy and communication, and secures adequate choice for all patients (Figure 17.5).

Studies on personal belongings in bed rooms of health care facilities

The recognition of the importance of personal belongings in the healing environment differs between hospitals and assisted living facilities. Various studies of assisted living facilities have shed light on the value of residents’ using their own possessions in everday activities (Toyama et al. 1997, 2002). The hypothesis is that a resident is more likely to undertake an activity when he/she can use a familiar personal object, such as a comb or hairbrush. This view recognizes the need for more space to accommodate personal belongings. In turn, the need for more floor area encouraged the trend to change the bed room environment from a four-bed room to a single-bed room. In contrast, according to a study by Imai and Maeda (1993), the situation is different in hospitals where multi-bed rooms are mainly used for efficiency. The study refers to the orderly use of storage in the limited space provided. The former view values the patients’ access to a variety of belongings and the latter requires the patients to sort their belongings in an orderly fashion.

FIGURE 17.4 Suggestion to make two inconsistent ideas possible in Japan

Source: Shiho Mori.

FIGURE 17.5 Ideal type of relations between privacy and communication

Source: Shiho Mori.

In our recent survey most patients tended to lie down on their beds. Various everyday activities were also carried out in that position. A physical environment design which allows for various patient positions is required to provide for better communication in order to enhance quicker recovery. Some patients place their beds closer to each other for easier communication. A flexible management rule or system should be established, so that users can position their beds freely (Figure 17.6).

Comments on bed room design

The following suggestions are made to better resolve the controversial issue of privacy versus communication:

1 The management system and environmental design should be realized to support the free and natural occurrence of communication among inpatients and their families.

2 It is important to furnish and implement the adjustments of interpersonal relationships among inpatients, and also to reduce unnecessary tight rules among them.

3 A series of common spaces in a variety of areas inside and outside hospital rooms should be created, and this should not impede the privacy of personal space.

These points may become future directions with a focus on the values of Asian people.

FIGURE 17.6 Example of adjusting interpersonal relationships

Source: Shiho Mori.

FIGURE 17.7 Schematic sketch of an impatient ward with all single rooms

Source: Akikazu Kato.

Figure 17.7 is a schematic sketch of an all single room inpatient ward for a Japanese hospital, which is inspired by the ward design of Katta Public General Hospital and the pod ward plan of G Hospital.

Conclusion

The chapter discussed the trends in hospital architecture critiques in Japan by contrasting tradition and fad, abstraction and embodiment, mega-structure and campus, urban center and village concept, PFI and non-PFI, and others. The juxtaposition is not merely suggestive of a dichotomy of values as in red versus white as in the flag of Japan. They are suggestive too as guidance for building performance evaluation in hospitals or other building types in Japan as well as in other parts of the world.

References

Aichi Children’s Health and Medical Center (n.d.) homepage for kids. http://www.achmc.pref.aichi.jp/Morino_nakama/S008.html

Ashiwara, Taro, Koh Kitayama, and Hideto Horiike (2002) “In Search of the Most Suitable Solution for Hospital Architecture: Interview with Three Architects.” Shin Kenchiku June: 128–30 [in Japanese].

Becker, Franklin (1990) The Total Workplace: Facilities Management and the Elastic Organization. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Cooper Marcus, Clare and Naomi A. Sachs (2013) Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces. New York: John Wiley.

Finch, Paul (2005a) “Doctors’ Orders.” Architectural Review May: 44–45.

Finch, Paul (2005b) “Light Touch, Evelina Children’s Hospital.” Architectural Review May: 46–55.

Imai, Shoji and Yoshihiro Maeda (1993) “A Study on the Needs of the Space Formation around In-Patients’ Beds.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 450: 57–62, Architectural Institute of Japan [in Japanese].

Kato, Akikazu, Kanae Mochizuki, Shiho Mori, and Masayuki Kato (2014) “Special Composition of Hospital Ward Plan Configuring Pod Plan Scheme from Traditional Nightingale Ward.” Proceedings of AIJ Tokai Branch Research Meeting 52, Architectural Institute of Japan [in Japanese].

Kobayashi, Hitoshi (2002) “Katta Public General Hospital.” Shin Kenchiku (New Architecture) June: 116–27 [in Japanese].

Mori, Shiho, Seng Kee Chan, Yoshinori Shinohara, Homare Tani, Hirofumi Higashizono, Yoshihiko Sano, and Akikazu Kato (2011) “Which is Better – a Single Bed Room Versus a Multiple Bed Room in a Hospital? Analysis on the Asian Way to Develop the Inpatient Environment.” Poster presentation 30421, at the UIA 2011 Tokyo, the 24th World Congress of Architecture Academic Program, September, ISBN 4-903378-09-1.

Mori, Shiho and Gen Taniguchi (2002) “A Study on Single Room Known by a Viewpoint of Homely Space: Studies on Environment Providing the Aspect of Dwelling for the Ederly.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 552: 109–15, Architectural Institute of Japan [in Japanese].

Padbury, James, Jesse Bender, and Marybeth Taub (2013) “Millennium Neonatology: A Building for the Future.” edra44 Providence Conference Proceedings: 229–30.

Stone, Peter (ed.) (1980) British Hospital and Health-Care Buildings: Designs and Appraisals. London: Architectural Press.

Thompson, John D. and Grace Goldin (1975) The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Toyama, Tadashi, Hiroshi Tachibana, Takashi Takahashi, and Toshie Koga (1997) “A Study on Personalization in Single Room of Nursing Home for the Elderly.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 500: 133–38, Architectural Institute of Japan [in Japanese].