Walking can be considered as a tool to experience, analyse and represent space in relation to subjectivity. Looking beyond its value as an everyday life activity, artists, philosophers, writers, architects and activists have seen its value as an aesthetic, political and relational practice. We trace this legacy of walking within the emergence of an alternative architecture and urbanism connecting movement, site and subjectivity, suggesting that this is rooted in those artistic practices and civic actions of the modern era that, starting in the nineteenth century, took up walking as an ontological, aesthetic and political knowledge tool. Revisiting some of them, we will ask what the role of walking might be in enabling a more intense experience and more precise reading of the city, how this might change the way we plan and build the city, and what the promise of walking is for future architectural and urban practice.

In his book Walkscapes, Francesco Careri suggests that the production of space began with human beings wandering in the Palaeolithic landscape, following traces, leaving traces.1 A slow appropriation of territory was the result of this incessant walking. Taking ‘walking’ as the beginning of architecture, Careri proposes an alternative history: one not concerned with settlements, cities and buildings, but with movements, displacements and flows. It is an architecture that speaks of space, not as contained by walls, but made of routes, paths and relationships. Careri suggests a common factor in the system of representation found in the plan of the Palaeolithic village, the walkabouts of the Australian aborigines and the psychogeographic maps of the Situationists. If, for the settler, the space between settlements is empty, for the nomad, the errant, the walker, this space is full of traces: they inhabit space through the points, lines, stains and impressions, through the material and symbolic marks that are left in the landscape.

Nomads were perhaps the first alternative urbanists, starting to organise space by tracing routes and paths. This sort of ‘urbanism’ is based on a particular logic: planning with the unknown, planning through experiencing, planning not place, but displacement. Not merely a functional means, walking became an aesthetic frame to discover the world. World literature is full of travel narratives dating back to antiquity, but one could say that walking became a truly aesthetic experience only within modernity. Portraying Paris in the nineteenth century, Charles Baudelaire, and later Walter Benjamin, showed how the modern city provides the ideal physical and cultural context for the experience of displacement, discovery and wandering.2 Writing about walking as a way of experiencing the city, they identified the emergence of a new urban subject, who walks across the modern city with its numerous facades, streets and displays as if crossing an unknown landscape, not crossing forests, but walls and streets among crowds. They recognised walking as a psychological and cultural experience, a product of the quality of the urban space and the subjectivity of the city dweller. Baudelaire identified a particular figure to express the dynamic physical and cultural condition of the modern city: the flâneur. He is a new type of city user, produced by the crowded condition of the modern city.

So he goes, he roams, he seeks. What is he looking for? With a sure aim this man I have depicted, this solitary person gifted with an active imagination, who is always traversing the vast desert of humanity, has a goal more elevated than that of the pure stroller [flâneur], a more general goal, quite apart from the fugitive pleasure of the moment. He searches for something we can call modernity, for there is no better word to express the idea in question. For him it is a matter of disengaging fashion from a poetic content founded in history, and instead finding the eternal within the transitory.3

With the flâneur, walking becomes a structural practice of modernity, concerned with seizing the ‘eternal within the transitory’.

Walking as aesthetic practice

The Dada artists, and after them the Surrealists, also celebrated this aesthetic quality in their organised visits to the city and its outskirts. This was the first time that art rejected the gallery to reclaim urban space. The ‘visit’ was one of the tools chosen by Dada to achieve that transition. Starting in 1924, they organised trips to the open country, discovering the dreamlike, surreal aspect of walking. They defined déambulation as a sort of automatic writing in real space, capable of revealing unconscious zones of space, the repressed areas of the city, in direct correlation with repressed areas of the psyche. The Surrealists continued this practice, organising group visits and meetings in particular urban places. They sought ‘places that had no reason to exist’ and, at the same time, they were also interested in the terrains vagues of creativity. Their narratives, and other aesthetic productions such as found objects, art installations and poetry, described the city in a new way.4 In 1950, the Lettrist International developed the Theorie de la dérive. For the Lettrists, the dérive was different from déambulation; it was not just physical and psychological, but also political and ideological: a deviation, a way of contesting.

The Situationists pushed the dérive and its subversive dimension further: it became a method to discover and to validate an alternative city, another architecture, not built through axes and frames. It was a way to disorganise and fragment the city through the experience of ‘drifting’, which would allow the psyche to reconstruct it in different ways. Dérive was defined by Guy Debord as not only an artistic but also a scientific practice: psychogeography, ‘the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals’.5

The Situationists directly attacked modern urban planning. They championed the pedestrian over the car, criticising the car-produced city and its specific urban forms: parking, highways, suburbs. They criticised the obsession with utility and function and, implicitly, the idea that form should be determined by function: the key principle of modern architecture and urbanism. Contemporary with, and in opposition to the Athens Charter, which stated the principles of modern urbanism, they proposed a New Urbanism, which encouraged the symbolic destruction of modern urbanism and its principles, recommending instead an unmediated approach to the city, through life experience and the invention of new urban practices within the everyday:

The architecture of tomorrow will be a means of modifying present conceptions of time and space. It will be a means of knowledge and a means of action. The architectural complex will be modifiable. Its aspect will change totally or partially in accordance with the will of its inhabitants.6

For engendering ‘situations’, walking was an everyday life practice that opposed the principles of modern urbanism. It was not cars, but pedestrians, walkers, wanderers, who were able to construct situations. In 1957, Constant Nieuwenhuys designed the camp of nomads of Alba as a model, and Guy Debord and Asger Jorn drifted into a ‘construction of situations’, experimenting with playful creative behaviour and creative environments. ‘Constructed situation: A moment of life concretely and deliberately constructed by the collective organization of a unitary ambiance and a game of events.’7 Nieuwenhuys developed this idea of constructed situations almost literally and reworked the Situationist theory into the realm of architecture, proposing a nomadic city: The New Babylon, a city in which human activity and culture do not relate to use anymore but to uselesness: ‘The new forces orient themselves towards a complex of human activities that extends beyond utility: leisure, superior games. Contrary to what the functionalists think, culture is situated at the point where usefulness ends’.8

Such a city also creates other types of user, whose activity is continual movement and play.

Walking as a way of being in the world

Contemporary with the Situationists, philosopher Michel de Certeau wrote, in his book Practice of Everyday Life, about walking as an everyday life practice, a practice difficult to define and represent in terms of urban practice, because it is at the same time a fundamental ontological experience: ‘a way of being in the world’.9 For de Certeau, the walking body moves in the city in search of something familiar. He invokes Freud, saying that walking recalls a baby’s moves inside the maternal body: ‘To walk is to be in search of a proper place. It is a process of being indefinitely absent and looking for a proper place’.10 De Certeau writes of ‘the spatial language’ of walking, but criticises the way it is representated in the urban cartographies of the time, as they do not represent the act of walking, which is no simple movement, but ‘a way of being in the world’.

Difficult to represent also is the banality of the everyday. Walking is one of the most banal experiences, located at ground level of our urban dwelling condition. But it is exactly in this difficulty that the power of walking as critical practice lies. It is owing to the street and the banality of everyday life that walking offers a radical way of conceptualising the city: a way of knowing to challenge the systematic, rationalising and functionalist ideas of the city imposed by the urban planners and managers. Because of its direct contact with the lived environment, walking is both a mode of being in the city and a way of knowing it. Drawing on Foucault’s critique of power, de Certeau finds in walking a form of resistance to distanced and privileged ways of visualising the city as a unified whole.11 Unlike Baudelaire, de Certeau refers to walking as a mass practice: the ‘“wandering of the semantic” produced by masses that make some parts of the city disappear while exaggerating others, distorting it, fragmenting it, and diverting it from its immobile order’.12 It is the ‘forest of gestures’ produced by the walking of the many that opposes the immobility of the city.

Walking as politics

There is a history of walking as critical mass practice in political struggles, of which protest marches are a part, one of the most emblematic being the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom of 28 August 1963. It involved all black civil rights and union leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr, and led to the passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. It was a landmark event for the early civil rights movement, with over 250,000 demonstrators converging on Washington, DC, to attend what became the largest public protest in the history of the United States.13 The power of marching as criticism and resistance has also been used in direct action events and artistic urban protests. Reclaim the Streets, a global movement in the 1990s, was a move to retake public space from cars and commerce for reuse in partying and strolling. It merged the direct action of Britain’s anti-road-building movement with the carnivalesque nature of the counter-cultural rave scene and served as catalyst for the global anti-capitalist movements of the late 1990s. Besides the protest element, its street parties also provided a prefigurative vision of what city streets could be in a system that prioritised people over profit, ecology over economy. The street critical mass anti-capitalist movement took different forms, using creative forms of protest and growing in scale: a global street party in seventy cities occurred in May 1998, coinciding with the G8 summit. A year later, the Carnival Against Capital on 18 June, coordinated by Reclaim the Streets and the People’s Global Action network, saw simultaneous actions in financial districts across the world, from Nigeria to Uruguay, North Korea and Australia to Belarus. In 2000, a carnivalesque mass street action shut down the World Trade Organisation in Seattle, an event that turned into the coming-out party for the anti-globalisation movement.14

Figure 2.3.1 Reclaim the Streets, Camden High Street, UK, 14 May 1995

Source: Nick Cobbing

Walking as architectural and urban practice

Walking is both an urban practice and an alternative mode of urban knowledge. As suggested by the Situationists, it announces the possibility of an alternative urbanism that is more dynamic, more critical and grounded in everyday life. Some contemporary architectural practices are pursuing this, such as Stalker, an architects’ collective in Rome, which was started in 1995 after the architects, as students, had occupied Rome University. One of their first projects was an exploration of Rome called ‘Through the actual territories’,15 which involved combing the uncertain territories of the city in a Situationist vein, making discoveries. As they felt they were re-enacting in a contemporary form transhumance (seasonal pasturage), they called their practice transurbance. It centred on the relation between the transitory urban subject and the city with its territories, but their practice was at the same time an everyday practice, a protest against traditional architecture. It offered a different way of reading and interpreting the city from the point of view of roaming. Not only the group was moving – other forms of movement were discovered latent in these territories: social and economic mutations, nomadic installations, temporary settlements. Along with the walk, they organised broadcasting sessions from the territories crossed, allowing their reading to be revealed and documented in real time.

‘Territory’ is also a political and geographic term, suggesting large-scale spatial politics and notions of power and control. In biology, it relates to spatial appropriation behaviour, defined geographic areas defended by an animal against others. In reaction against this, Stalker proposed another way of reading urban territories: instead of appropriating and controlling them, crossing them. The attempt to ‘control’ territories is a fundamental principle of modern urbanism and probably of Western culture in general. In their tour of Rome, Stalker discovered the emergence of the uncontrolled within the core of a highly organised city that had been based on principles of control and appropriation. Most dynamics would take place at the edge, the margin, the border, on the fringe of defined territorial entities, where rules are softer and ecosystems overlap. Like Dada and the Surrealists, they discovered and celebrated the terrains vagues of the contemporary city.

There are many terms for terrain vague: abandoned field, no-man’s-land, vacant lot, wasteland, friche (urban leftover). Walking across the empty plots and the voids of the city was a way to acknowledge abandonment as a form of preserving territories, a way of conserving entropy within the city. Terrain vague is a place of life, an urban wilderness, a way of preserving what has developed in the shadow of human behaviour. There is a connection between disuse and a sense of freedom. Terrain vague tends to be inhabited by species that enjoy freedom, that resist control and domestication: weeds, wild birds and also, sometimes, populations wishing to resist the system; it is the emergence of the margin in the centre.

Stalker’s practice shows the importance of including the evocative, paradoxical power of the terrain vague in the perception of the contemporary city. Terrain vague represents (some -times literally) the entropic, degenerate, troubled element that is opposed to the authority of architecture. The vagueness of the terrains vagues stands against the planned hygienist vacuity of modern urbanism. Stalker’s urban stroll across the terrains vagues celebrates the city’s resistance to urbanisation. Their walking reveals the city as a process and concentrates aesthetic and ethical questions raised by contemporary society, such as how we can preserve life within the city, and how we can value what is not under our control. Stalker propose precise techniques of observation and mapping: ‘A nomadic research, a mode of capturing the act of crossing without regimentation, ratification or definition of the object examined, so as not to prevent its becoming’.16

Figure 2.3.2 ‘Through the actual territories’, Rome 1996, project by architects’ collective Stalker in Rome to explore uncertain territories of the city in a Situationist vein

Source: Stalker

In 2004, at the invitation of the Serpentine Gallery, known for commissioning temporary pavilions by star architects, public works proposed instead a roaming stall within Kensington Park, creating relations between the park’s many users. The Park Products project questioned existing spaces for cultural production and distribution and suggested new ones, which arose through the practice of taking walks in the park and meeting people.17 The outcomes from those meetings – the ‘park products’ – later took on the same mobility, moving again through the park. They joke about their ‘pavilion’, which, in contrast with the usual ones, was conceived as a gathering of people and objects, rather than as an iconic piece of architecture. It was a provocation, making the static institution of Serpentine go for a walk in its own immediate environment. The project reclaimed space through strolling, playing and chatting, but it was also a way to subvert the symbolic value of the profession of architect as normally constructed around the idea of building. This is a vital message: the discovery that there are people out there, that space is never abstract and static, but that it always exists in relation to those who use it. For public works, the architecture of walking is a form of relationality. It is a more ecological and democratic way of creating space.

Figure 2.3.3 The Park Products, Mobile Porch, London 2002 project by public works

Source: public works

Figure 2.3.4 Transhumance at Ferme du Bonheur, Nanterre, 2012

Source: C. Petcou

Walking as post-humanistic practice

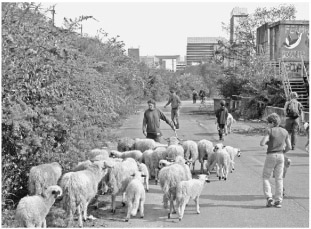

Walking has retained its value as a way of discovering the city. Many cultural and architectural institutions now organise walks with residents as part of their outreach programmes, as a form of pedagogy that aims at teaching architecture in the outside world, beyond the boundaries of the institution, allowing for informal postures within the learning process. Some civic organisations propose forms of walking derived from old traditions and cultures. In Madrid, for example, after much political and ecological struggle, the migration of livestock through the city has been reauthorised, with the temporary closure of certain streets to cars.18 The ancient transhumance paths pre-existed the city, so that this change restores a historic right. This success also registered the need to see the city from another perspective, to make visible the presence of animals, fellow species that also walk. Such practices allow us better to understand the city as an ecosystem, as a space to be shared with others – animals, plants – and to find new ways of thinking about it, planning it in a more ecological and post-humanistic manner. From this perspective, walking is one of the most resilient practices involved in the servicing of the ecosystem: a form of civic care, of preservation, not just of human otherness but of all ‘more than human’ others – meaning, not only other species, but all of non-human materiality, including bacteria, minerals, air, rivers etc. – ultimately, anything that contributes to our own settlements.19

The architecture of walking offers reflection in open-ended ways: its study opens up the possibility to review existing situations to learn from a city and its practices, rather than imposing preconceived notions of what a city should be. It offers an alternative knowledge of the city, to be shared and performed by many. It bears the promise of a grounded, sensitive and democratic production of space that was always there as a fundamental practice, but that can be rediscovered, preserved and refined by future urban and architectural practices.

Notes

1 Careri 2002.

2 Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris the capital of the nineteen century’, in Benjamin 2002.

3 Baudelaire 2010, p. 12.

4 Breton’s Mad Love is only one of the best-known examples of such creations.

5 Guy Debord (1955) Introduction to a critique of urban geography, in Les Lèvres Nues, vol. 6.

6 Ivan Chtcheglov (alias Gilles Ivain), Formulaire pour un urbanisme nouveau (1953), reprinted in (1958) Internationale Situationniste [Situationist International], vol. 1. Available online at: www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/definitions.html (accessed 15 June 2013).

7 Unsigned, ‘Definitions’, in (1958) Internationale Situationniste [Situationist International], vol. 1. Available at: www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/definitions.html (accessed 15 June 2013).

8 Armando A. Alberts and Har Oudejans Constant (1959) First proclamation of the Dutch Section of IS, in Internationale Situationniste, vol. 3.

9 De Certeau 1984, p. 109.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., p. 96.

12 Ibid., p. 102.

13 Shepard and Hayduk 2002.

14 cf. Stalker manifesto. Available at: http://digilander.libero.it/stalkerlab/tarkowsky/manifesto/manifesting.htm (accessed 9 June 2013).

15 The ‘actual’, according to Deleuze and Guattari, is not what it is (the present) and not what it will be (the virtual), but what it is going to be, what it is in the process of becoming. See Deleuze and Guattari 2004.

16 Stalker manifesto.

17 Park Products is a project by Kathrin Böhm and Andreas Lang from public works, commissioned by Sally Tallant for the Serpentine Gallery, London 2003–4.

18 Every year in November, thousands of sheep cross Madrid during one day, on their way to the South. The event is called Fiesta de la Transhumancia (Transhumance Festival) and is sort of homage to the farming community and the migration of livestock. The migration of livestock to the South has happened for centuries – the weather is warmer in the winter, and farmers move their livestock from the cooler mountainous regions, which soon become covered with snow. The warmer weather of the South allows the livestock to feed on grass during the winter. Until the seventeenth century, there were 5 million sheep crossing the pensinsula twice a year; now, there are only 1 million.

19 These ideas are supported by currents of post-humanist humanities, with representative thinkers such as Val Plumwood from the ecological humanities, or Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour and other thinkers on the technology of nature.