5

Ascribing Otherness and the Threat to the Self: Representations of Slums and the Social Space of Others

In Buitengracht-street, the Princess was attracted by a beautifully designed but dilapidated old Dutch house. Most of its windows were shattered and its oak panelled hall was serving as a communal kitchen. Past this house, but a few generations ago, the British Governors of the Cape and the flower of Cape Town’s society used to parade in the evening. Lady Anne Barnard, it is said, knew it well. Yesterday Princess Alice found it harbouring incredible squalor.1

The Cape Times, ‘Princess Alice in Slumland’

In 1929, Princess Alice went down the rabbit hole and landed up in ‘Slumland’. And like Wonderland it was busy with disturbing characters. For ‘the slum’ loomed large in the popular imagination as a weird liminal space at the edge of middle-class respectability. Slumland threatened the loss of the Self and, without much exaggeration, the whole of Western Civilization – as so clearly symbolized by the fate suffered by the old Dutch house and its associated ghosts of Empire described above. Off with her head indeed. But it was surprisingly only one of many rabbit holes that the Princess managed to fall into in the course of her duties as the Vicereine of South Africa; Old Cape Town was riddled with them – or so it seemed. As we shall see below, newspaper articles and official reports often described places like District Six as rabbit warrens filled with animal-like humans. In the broad brushstrokes of sensationalist journalism and the finer details of official reports, District Six and Old Cape Town was depicted – ascribed – as the location of Otherness. But ascribing Otherness worked in dual ways, locking the inhabitants inside the tainting walls of derelict buildings, or alternatively, the ‘animalistic’ inhabitants tainting the walls of the housing stock by miasmic association. This slippage is rife in discourse on ‘slums’ and is tellingly present when the Garden Cities and Town Planning journal tried to define ‘what is a slum?’2 Verbatim extracts of George Duckworth’s paper read at the RIBA give the answer:

A slum, then, is a street, court or alley which reflects the social condition of a poor, thriftless, irregularly employed and rough class of inhabitant. The outward signs are bread and litter in the streets; windows dirty, broken and patched with brown or white paper; curtains dirty and frayed and blinds half drawn and often hanging at an angle. The street doors are usually open, showing bare passages and stairways lacking balustrades, while the door jambs are generally brown with dirt and rubbed shiny by the coats of the leisured class, whose habits are to lean up against them.

The transference and slippage between building and person is beautifully and literally articulated in the last sentence – the dirt of the building rubbed off onto the skin of the loitering unemployed, and the dirty practice of loitering ironically becoming a cleansing, rather than the tainting, of dirty buildings.

In Cape Town, the ‘slums’ of District Six and parts of Old Cape Town were stigmatized and devalued, opening both the inhabitants, and the buildings, eventually to forced removal and relocation. And solidifying the nascent race politics of a divided South Africa to boot. For the act of ascribing Otherness was also the consolidating of the Self; every hyperbole employed to shock the reader was a strengthening of the veracity of the project of Empire, of the ‘obvious hierarchy’ of races and cultures. Imperial discourse on the architecture and inhabitants of the slums became a key founding layer in the construction of apartheid. And it is to this discourse that we now turn.

ASCRIBING OTHERNESS: ‘KENNELS’, ‘HOVELS’, AND OTHER ANIMALISTIC ASSOCIATIONS

From newspapers3 and magazines,4 to petitions,5 conferences,6 and official documents7 the word ‘hovel’ is ubiquitous in the 40-odd years this book covers. Although words like ‘pondokkie’8 and ‘shanty’ were occasionally used, especially towards the end of the period of study and mostly to describe peri-urban dwellings, ‘hovel’ associated the ‘slum’ dweller with an animal status.9 It should be noted, however, that many of the descriptions of dwelling spaces using this emotionally charged word, especially those after the ’flu epidemic of 1918, were intended to shock the general public and officials into providing some form of social housing or better health conditions in certain areas. Nevertheless, the use of this word in identifying and describing Other-spaces reinforced the identity of those inhabitants as Other. It was used as early as 1888 to undermine the voting rights of recently urbanized Natives living in the city: As J. Easton, ruminating on Four Questions of the Day admonished the reader: ‘Think for a moment of that ignorant and disgustingly dirty fellow, the occupier of one of these wretched hovels, having a voice in the government of this town equal to that of the mayor himself.’10 Clearly, a ‘hovel’ did not constitute the legitimizing capacity that property-based voting rights were intended to bestow.

The link between slum-dwellers and the animal world was often made through words other than ‘hovel.’ In an article titled ‘A Hotbed of Horrors,’ the Architect, Builder & Engineer ran an exposé on slum conditions, choosing Wells Square – a place of much notoriety to be explored in the following chapter – as their focus.11 In this example, the association of the urban poor with the animal world is made very clear: ‘It may have been a square once; it’s a sink now. What once was open space is covered by hovels, kennels, rabbit warrens, call them what you will, but for Heaven’s sake don’t call them human habitations.’ For their part the Cape Times ran a series of reports on the ‘Underworld of Cape Town’ where the association of human ‘type’ with dwelling ‘type’ is defined:

Within a stone’s throw of the University [in the city] exist squalid hutches and warrens occupied by people of colour who could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be described as the better class. These premises are being whitewashed now. The landlords have had a shaking up [from the series]. Perhaps they fear demolition.12

And in 1918 the City Council, after the tour they took of the city’s poorer neighbourhoods, reported seeing ‘the dens and kennels in which people lived worse than rats.’13 At a much later date the Cape Times was still calling poor people ‘sub-human’14 through their association with their dwellings. The simple act of naming and associating people with animal-like dwellings ascribed a sense of Otherness that would ultimately bolster and naturalize segregationist ambitions.

The primary concern that drove most of the writing on slums was the condition alternatively called ‘overcrowding’ and ‘congestion.’ As was noted in the previous chapter, the latter term was also used to describe the aesthetic problems with the density of buildings in the city, but it was the density and number of bodies in dwellings that was typically meant by the word. Congestion, in these terms, was one of the major causes for concern for the agents of Empire. In the shadow of Victorian morality and the required separation of sexes, it was generally understood that ‘living under such conditions [of congestion and overcrowding] is not only bad physically, but also bad morally.’15 Although there were sentiments to the contrary, the overwhelming consideration was that this condition of dense living was endemic – essential – to the Native and Others in general. Again, animal-like adjectives reinforced this perceived condition as problematic and threatening. We find this in the records of the Commission for a Native Location for Cape Town in 1901 (hereafter CNL) concerning District Six:

We have a considerable amount of overcrowding among the low-class Jews. The Kafirs seem to like to herd together; they would prefer to have a room filled. The Europeans prefer the reverse, and it is the result of circumstances that they herd together.16

Again, the animal qualities associated with the word ‘herd’ are fairly obvious. These generalizations were echoed by Robert Wynne-Roberts, the City Engineer of Cape Town, who was of the opinion that a satellite Native ‘location’ was not desirable and preferred the supervisory possibilities that lodging-houses could apply in ‘civilizing’ Natives:

You would be able to have supervision over them. They want to live under conditions they are used to live. They like to huddle up together. If they are under the lodging-house principle you can get them to live in a more civilized way by force. You will in this way do the native more good than anything you can think of. Once you begin to improve his morals in that respect you raise him to a higher level. If the natives are in a location they would be huddled together as they please, and you cannot expect to improve them in this way.17

Whatever the City Engineer’s paternalist intentions, Natives, it seemed, ‘naturally’ preferred to live ‘huddled together.’ This essentialist attitude also carried through to the view that it was ‘their nature’ to spoil: ‘If some people were put in the Governor’s house they would soon turn it into a condition worse than a Kafir kraal.’18 Others lamented the ‘noteworthy ease with which natives usually adapt themselves to slum conditions.’19 Whilst a report by the Department of Native Affairs in 1919 suggested: ‘So long as the native is content to live in squalor so long will the native population of the towns be an offence and menace to the European section of the community.’20 It followed then, that Natives were somehow naturally unable to keep ‘their’ living quarters in any kind of decent order, whilst the sentence itself hints that this should be enough to legitimize the possible dispossession of natives from their dwellings in the city.

The idea that Others had a natural tendency of living in dense areas cut across the then hardening racial lines: Coloureds were considered as prone to dense living as Natives.

On a ‘Visit of Inspection’ to Wells Square, the Municipal Reform Association stated matter-of-factly that they found ‘as many as 17 [coloureds] living in one house.’21 For the English middle class the tendency was for four or five people to occupy a house; this statistic would have been beyond the need for hyperbole and would have been enough in itself to induce shudders. A few years later, at a conference between the government’s Central Housing Board and the city’s Housing and Estates Committee (hereafter Housing Committee) to consider a housing scheme for Coloureds, it was reported that ‘Councillor Zoutendyk stated that the object of the Scheme was to get rid of the congested areas. He pointed out that it was very difficult to get the people in District Six out of their “hovels,” even if they were offered nice houses. They would rather live in congested areas.’22 For that matter consider the following quote which links the increase in density of bodies in space to an increase in social degenerates. The particular locality under consideration is the area of District Six that was known as the ‘Dry Docks’ which, contrary to expectations of its name was at the foot of Devil’s Peak mountain, just below the recently developed De Waal Drive:

Seventeen years ago, when we first started mission work there, the cottages were inhabited by very decent coloured folk, each family occupying a room and occasionally two rooms. But now things have altered and the overcrowding is deplorable, two and in some cases three families living and sleeping in one room, 12 × 12 feet. And even then only one family rents a room. They sometimes take in a lodger or two. Many of the respectable people are still there and trying to live good, quiet lives, but there are dilapidated rooms abutting on filthy backyards which are not fit for human habitation, which shelter numbers of girls and men of the lowest type.23

District Six and its ‘hovels’ were being conflated with a particular kind of unfathomable person happy to live in dense, sub-human conditions. But it was not just particular areas of Old Cape Town that were problematic. The whole idea of urban living in general was considered degenerate, and could literally lead to a genetic degeneracy.24 Just in case they forgot themselves, the Central Housing Board’s report of 1935 quotes Raymond Unwin on just how different the English are in terms of domestic space. Unwin, who, as we shall see in the third part of this book, had a definitive influence on domestic space had this to say: ‘The English people retain their love of individuality for themselves and their family life which springs largely from their cottage homes … They dislike the “herd” life and the “herd” mind which tenement existence is liable to foster.’25 That a family would choose to live in a tenement or a flat was largely incomprehensible. Consider the cultural self-assuredness in the following quote from the 1935 report of the Central Housing Board, which was the main organ of central government financing municipal housing: ‘On the continent of Europe, flats are provided for many classes of workers, most of whom are owing to the nature of government control inarticulate as to their desires or wishes for home life.’26 In other words, were they able to protest, then their choice would naturally go against the flat and be in favour of the single-family detached unit. Yet the sentence carries with it the innuendo that continental Europeans – those other than English – could be and were marked as Other by their choice of dwelling type. ‘Neighbours have nothing in common, not even a cabbage patch, and the tenant of a flat cannot forget that neither he, nor his neighbour, is “king of the castle.”’27 It would seem that those who lived in flats then were all ‘dirty rascals.’ This Othering also played its part with regards the idea of degeneracy, the logic being that given a choice nobody would consider flats as a desirable dwelling type, therefore, its inhabitants must either be indigent, or more simply, prone to degeneracy.

There were, however, some voices that suggested that people who lived in overcrowded dwellings in Old Cape Town did so not because they chose to or were innately programmed to, but because they could afford nothing else. The sentiment of helping the ‘worthy poor’ was summed up by Princess Alice at her opening speech for Cape Town’s Housing Week in 1929:

You cannot expect decency, morality, or health under such conditions. And yet, if you or I were forced to pay a rent we could not afford, and were faced with hungry children, why, I am certain we should do exactly the same! There are lots of decent, respectable people struggling along in those frightful conditions, whose marvellous patience and resignation are beyond praise. But that is no reason why their poverty should be exploited as it so obviously is in many cases.28

Nevertheless, the majority of reports and representations depicted high density living as confirmation of the difference of those people already marked as such due to other indicators such as skin colour, language and dress. Caught up within this confirmation was the further Othering that suggested that this propensity to dense living was a ‘natural’ phenomenon for a variety of groups of people who, due to their racial inferiority, were also close to animals in their dwelling habits and character. The fact that many families were of an extended or, non-nuclear, type is another point that may have created the sense that they were Other. Whatever its cause, the ‘herding,’ perhaps hinting at the dangerous animal world of ‘Africa,’ struck the agents of Empire as a condition needing to be controlled and eradicated.

CONTAMINATION AND THE THREAT TO CIVILIZATION AND THE SELF

Slums and Other-spaces of Cape Town were viewed by most of the middle-class and those in power as a threat ‘to civilisation, to humanity, and to Christianity.’29 Throughout the period of study, and ranging from magazines30 to civic meetings,31 slums were represented as a direct threat to Western civilization, which needed protection from this cancerous attack. What exactly constituted this threat, what allowed Dr Jane Waterston to state ‘Nothing sickens me more than the manner in which these people live in this town,’32 and what potential effects this had on the reordering of Cape Town is the subject of the following section. It explores, in particular, the problem that the bodies of servants and Others coming into White homes presented to the agents of Empire.

Within many and various verbal representations, Other-spaces were often made threateningly present in the spaces of the Self. Unlike overcrowding, where the threat to Western civilization was to come indirectly through the ‘natural’ degeneracy of particular groups, here the threat was to come directly through the ‘contaminated’ body of servants or through the inanimate objects touched or serviced by Others in spaces represented as Other, and thereby into the home of the Self or directly onto the body of the Self through ‘contaminated’ clothing. Typically it was servants themselves, or rather, their bodies entering the home who were the main focus of this perceived threat. The following quotes can be taken as exemplary of the kind of sentiment often expressed:

In Cape Town, the people of the slums come into the houses of Sea Point, Rondebosch and Wynberg as servants, housemaids, and ‘boys:’ they become cooks and washerwomen. They handle the food Europeans eat, make and wash the clothes Europeans wear, tend and even nurse European babies. I wonder how many infectious and contagious diseases have been introduced into European homes by servants?33

It was not only newspapers that carried such sentiments. In an editorial in the Architect, Builder & Engineer on the need for housing and written after a visit to Parkwood on the Cape Flats, the author ominously noted that it was ‘out of these squalid kennels that we saw servants go forth to work in such homes as yours and ours.’34 Yet it was not only the movement of servants into the Home that was deemed a threat. As the Cape Times rightly recognized, the urban poor were the backbone of the colonizer’s economy and wealth and were always, therefore, connecting the Self to their ‘hovels’ through inanimate objects, especially clothing and food:

Somewhere or other in Cape Town – either in insect-infested huts in Ndabeni or in dirty pens in city hovels – are living men and women, black and coloured, who handle daily most of the things we eat and wear. The pollution which surrounds them at night touches us all somewhere by day. Here are the real foundations of our civilisation – embedded in the filthy ooze of a human cesspool. We spend many thousands a year on maintaining a costly public health service, and at any moment a dirty, plague-stricken native from one of the underground haunts of Cape Town – where infection, once lodged, is bound to spread like a consuming fire – can blow the whole edifice of our security to pieces with one hot breath.35

In many of the articles on ‘slums,’ the use of space, and how this related directly to the Self through the handling of things ‘we eat and wear,’ was identified as a major cause for concern. Not only was the holdall phrase ‘hovel’ used to summarize the Otherness of the space, but care was taken to describe in detail the surroundings in which these Others worked and lived as this quote on Wells Square (Figure 5.1) illustrates:

In one case we saw a coloured cobbler working at an open window of the smallest size, through which appeared a room of not more than one hundred square feet. In this were several beds. The flooring was decayed, the worker and his surroundings indescribably filthy. Whose boots was he mending?36

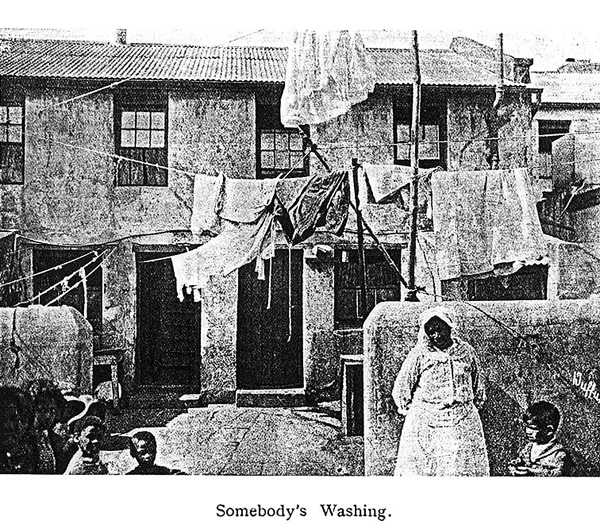

A similar concern was voiced over washerwomen who provided a service to the English middle class residents of Cape Town. Again, what is of interest is the way in which the activities of the washerwomen and their use of space are carefully noted:

We found that many of the tenants of these dwellings carry on the occupation of washerwomen, and during our visit these people were openly carrying on their vocation, the clothes being washed, in many instances, outside the front doors, adjacent to the lavatories, the ironing being performed indoors. From the nature of the garments hanging on the lines, it was at once apparent that they came from good families, and it is unnecessary for us to point out the serious consequences which must necessarily result from such practices if they are allowed to continue.37

The middle-class were urged to literally enter the space of the Other for their own good: ‘If Europeans would only go, and see for themselves the filthy conditions under which natives live, they would think twice before admitting them to their houses while living under such insanitary conditions.’38 This urging to visit the interior of Other-spaces became increasingly poignant later when the Slums Act was declared in 1934. Even though it looked – the Cape Times noted – ‘solid and respectable from the street,’39 a building in District Six was one of the first to be declared a slum. Any building, thus, could harbour out of sight a condition that was abhorrent and dangerous. Deception potentially lay in every respectable façade. Yet these instructions to enter Other-spaces also carried with it the urging to reform. No less than for the good of the nation were women urged to ‘concern herself with the what concerns her most – look after, say, the homes of those who are working for her – her servant and her washer-woman, and her errand-boy, if she has one, or any of her husband’s employees.’40

5.1 Wells Square, ‘A Hotbed of Horrors’

It is easy to dismiss the newspaper articles and the sensationalism associated with tabloid journalism. Yet these reports affected the ordering of the city as a White space. As we saw in the previous section they helped ascribe and confirm the difference of Others through the use of animal adjectives in their description of Other-spaces and through the idea that those inhabiting them had a natural tendency to live like animals in overcrowded conditions or slums – the presence of the Other in the city was shown to be an indirect threat to civilization. It was also made to seem a direct threat to health and the biological wellbeing of the Self and ‘good families’ as these reports laboured to illustrate a series of connections across space that linked Other-spaces with spaces of the Self. Through a set of rhetorical devices these Other-spaces are always potentially present in the Home, either through the body of the Other or through their contact with the things used and belonging to the Self. One’s own domestic space was suddenly perilous. These articles confirmed racial hierarchy and reinforced a sense that the presence of Others in the city needed to be controlled and eradicated. On entering these places and reporting their findings in painstaking detail, journalists became part of the mapping out of the interior space of Otherness. This mapping out of ‘strange’ interiors helped order the city as a White space. The use of the interior space of the slums and how that space was structured, or rather, unstructured, was necessarily part of the business of the middle class and it is to this that we now turn.

LOOSE BOUNDARIES: MISCEGENATION, AND THE THREAT OF ‘CONTACT’

A major threat the slums held for the White middle class was the interracial mixing that its social spaces encouraged. Yet they were not alone in their concerns; almost all those who cared to contemplate this aspect of slum-life, whether Black intellectual or White architect, considered the mixing and potential miscegenation it presented as a problem. The initial concern for racial intermixture in Other-spaces was the relationship between Natives and Coloureds, often signified through the word ‘contact’. Dr Abdurahman, the only Coloured member of the Cape Town City Council for many years, as part of the Overcrowding Sub-Committee, was concerned that ‘natives should not be allowed to come into contact with the coloured people of the City.’ Although it is not stated exactly why, it is quite possible that Abdurahman, along with many others, would have explained this as being crucial for the good of both ‘races,’ or for that matter, could have been intending to protect either one of them. In fact the idea of needing to ‘protect’ the Native who was considered ‘an unlettered child of the rural area … brought into contact with the degrading concomitants of civilized conditions,’41 had defined ‘the Native problem.’ As we shall see in Chapter 7, this idea of shielding from contact with the temptations – in a word, alcohol – of the city for their own good was one of the strong moral arguments used in favour of the production of the city as a White space. But Dr Abdurahman’s concern for the threat could have easily been read the other way. The editorial of the Cape Times had early on stated that ‘The aboriginal populations of the East are altogether alien to the manners and methods of the West, and their sense of decency and public decorum is different from those of the respectable coloured classes of the city into whose localities they are at present forced.’42 Some 20 years later in reference to the increased residence of Natives in the city, or more correctly ‘influx‘ into ‘coloured quarters,’ the Cape Times called it a ‘crime,’43 meaning that the phenomenon was a threat to Coloureds and that this ‘crime’ was caused by Natives.

The dominant concern was for the poor White residents of the city, particularly those living in the slums. In fact, the Housing Survey of the MOH had specifically included the extent of the mixing of races as one of its statistical findings.44 The Architect, Builder & Engineer saw fit to urge the state to deal with the dangers of having those of European descent having to live ‘in close proximity to those of other races.’ In their view, ‘the peril is by no means confined to the spread of disease and crime; it may threaten white civilization in the continent of Africa.’45 The potential for miscegenation, the entering of ‘the continent of Africa’ into the body of ‘white civilization’ through the loose boundaries of the slum, is a good example of how the slum was seen as a place of danger to the identity of the Self indexed through ‘white civilization.’ Slums potentially threatened the ever-anxious boundaries of White identity. The following excerpt comes from a report in the Cape Times regarding the tour of Cape Town’s slums during Housing Week in which parliamentarians took part:

Europeans lived often in the same houses with coloured people. The children played together, and in the evening shared the same slice of bread. Indeed, on the levels on which those Europeans exist the party discovered that the taboos and inhibitions of their race were tending to lose much of their power. On that level, one of them remarked, would not intermixture be easy for them, and perhaps even desirable?46

And further:

Dr. Van Broekhuizen, M.L.A. for Wonderboom, Transvaal, was especially distressed over the casual way in which white, coloured and black people are intermixed in the slums, often inhabiting the same house, and on occasions even sharing the same room. He was firmly convinced that the first step towards solving the housing problem in Cape Town ought to be rigid segregation of the white, coloured and black classes.47

It was not only politicians who considered the segregation of races through slum clearances and re-housing as an integral part of the housing ‘problem.’ The Chairman of the South African District of the Institute of Municipal and County Engineers, R.W. Watson, in an official address, felt that the municipalities did not have the legal power to solve ‘the problems arising out of the clashing of East and West in South Africa’48 by enforcing racial segregation, but considered this a major failing:

The removal of that considerable proportion of the native population, especially married natives, whose present conditions of living are at once unhealthy and a menace to the health of others, to suitably laid out villages or locations is a duty of prime importance.49

Statements such as those made by the parliamentarians and Watson, whether motivated by theories of racial supremacy and degeneracy or not, pointed to the potential loss of identity through miscegenation or ‘blood contamination’50 brought on by the intermingling proximity of living that Old Cape Town offered. This potential loss of clear racial and ethnic identities through miscegenation was also linked to the potential loss of the armature of supercilious confidence towards Natives through which White people were able to emotionally continue the colonial project. Concern was also voiced that White people living in the slums would become ‘demoralized,’ by having no choice but to live with Others.51 Once there, they would remain moribund and then degenerate further, losing their Whiteness. This problem of degeneracy was based on the idea that the respect of Natives and Others for Europeans needed to be maintained at all times to avoid a loss of face, and a potential loss of power.52 Whiteness needed to be seen as wholly unassailable. In fact, the report of the government’s 1920 housing commission states unequivocally that:

The poor whites, as we have seen are living in the most degrading and undesirable conditions in many of the towns, and having regard to the preponderance of the black population and the importance, as all believe, of maintaining the prestige of the white race, this class of people not only cannot be permitted to remain as they are, but should be compelled to re-instate themselves in what must be their proper standing in the social scale.53

This ‘standing on the social scale,’ no doubt included those necessary accoutrements of the Self: a happy Home and an edifying History that the Cape Dutch preservation movement was intended to secure. Not all European residents of slum areas would have been ‘poor whites.’ It should be noted that District Six, for example, had many residents with European and Jewish surnames, many of whom were owners of property there.54 Or, one may consider an article in the Cape Times in 1911 relaying the ‘remarkable contrasts’ of the area where one found the ‘unconcern of the Malays, the ox-eyed calm of the Indians, and the alert, intelligent look of the Jews are all displayed in even a section of a street.’55 District Six, as a heterogeneous place, complicated the agents of Empire’s wish for a segregated social-spatial order. Whether due to the threat of ‘noble natives’ learning immoral behaviour, or the potential loss of racial identity and thereby the clarity of ‘correctness’ in the colonial project, it was very plainly thought – even for those campaigning for the right to vote for women – that ‘the unregulated mixture of colour in congested areas was a cause of social degradation for all.’56

Apart from miscegenation fears, reports on the slums also suggest fears over the erosion of Self. Contained within the battlefield-inspired spatial metaphors of newspaper reports is a sense that Others were dominating or gaining increasing control over areas that were formerly places of the White Self. The lack of borders, or the permeability of borders around slum areas, was profoundly disturbing. Consider the similar sense of loss and danger in the following two separate newspaper reports:

Here are whole streets of once good-class residential property entirely given up to coloured house-holders and shop-keepers. The decline is startling enough by day. But by night it becomes even more marked. For then, as the native workers of the city troop home to their dismal lodgings, a further stage in the degeneration of the city becomes apparent.57

And

Decent streets, one by one, have fallen, by force of circumstances over which the most energetic and cleanly housewives exercised no sort of control, into the most deadly slums. Cellars and back rooms (meant for wood or coal) became by degrees, the homes of whole families, which includes, almost always some relations in addition to the parents and children.58

This second quote leads us into two key aspects of the following sections. First the idea of specific rooms being named and related to specific functions as hinted by the phrase ‘meant for wood or coal,’ and secondly, the idea of the non-nuclear family as suggested by the phrase ‘some relations in addition.’ It is to this latter condition that we turn to first.

THE MISUSE OF SPACE: CONGESTION AND FUNCTION

The density of bodies present in a room – a condition referred to as ‘congestion’ – was one of the dominant concerns brought into focus by the slums. The urban poor were said to live ‘huddled’ together confirming their animalized status as Other. This section gets at how the actual condition of ‘congestion’ was considered problematic.

Whilst fears of the spread of disease in these conditions was genuine – albeit a somewhat facile concern for the impact on labour and how that carrier labour force may transmit disease to the privileged – it was the strongly held opinion that an excess of people in one room would also constitute a collapse of moral health.

In a society where non-nuclear families were quite customary, due to a culture where extended families were the norm or the poverty-based necessities of sharing, this condemnation was onerous. Besides, this concern for non-nuclear family spaces was not simply over the moral health of those occupying the spaces, but reflected how tenuous the values and conditions of Whiteness were and how the Self could be lost unless continually re-made. This dual consideration can be traced in the tone of many of the sensationalist articles that conducted exposés on the congested areas of Old Cape Town. Even in conditions of lower densities or less overcrowding, the possibility of a non-nuclear family escaping moral judgement was slim. A little more than a third of the 15,750 people living in one-room lettings in Districts Two to Six in 1932 were part of a rental pattern that involved more adults than two parents in the same room.59 An uncle or an aunt, or two sets of parents sharing a single dwelling with their children, was not a possibility those in power were often willing to accept. The MOH stated his view of this phenomenon in the Housing Survey Interim Report:

All the activities of home life are concentrated in the one room. It is the bedroom and dressing room for everyone in the household, no matter what the age or sex, the living room, the room for meals, and the only place where food, clothing and household requisites can be stowed away. Except when there is a common kitchen also available, it is the room where the food must be cooked, and the ‘washing up’ done after cooking and eating (nearly always with no sink in the room), and where the members of the household must wash and take their baths. In time of illness the same room is the sick chamber, and it is the scene of childbirth and of death … The only acceptable standard is that every household should have separate bedroom accommodation for (1) the parents, (2) the other adult males and (3) the other adult females; and, in addition, one room for use as living room and kitchen and for other daytime purposes. Nothing less will allow of the necessary standards of health, decency and culture.60

And the report of the Union Government’s Housing Committee

There can be no privacy or decency in life when a whole family occupies one room, and practically all the poorer coloured people and many of the poorer white people in Cape Town to-day are living a family to a room.61

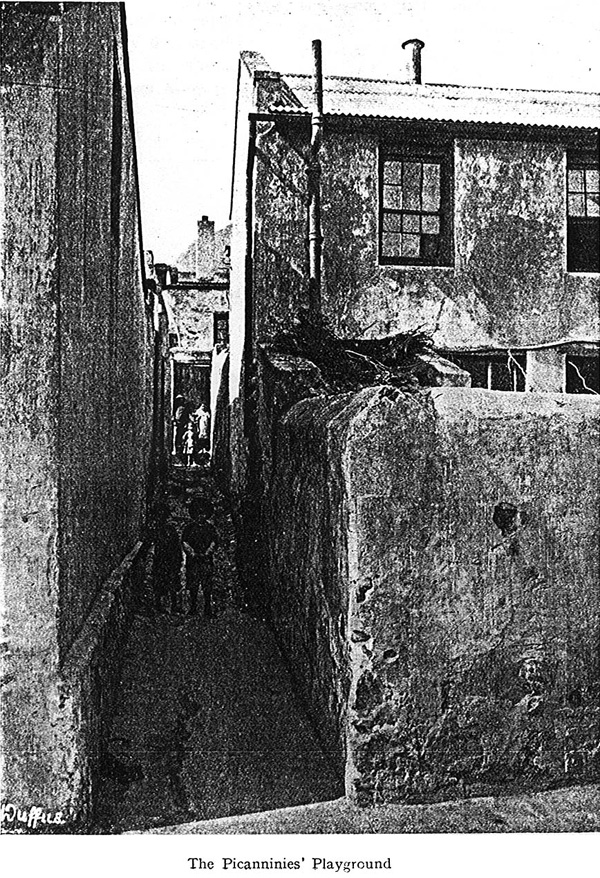

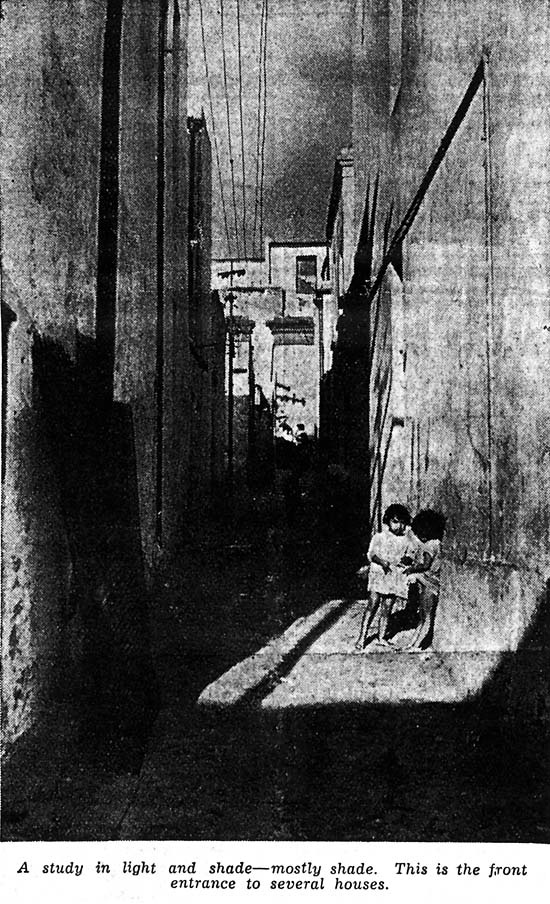

These quotes hint at a strong underlying belief of the time, namely the clear separation of functions into distinct spaces, represented in the case above by the need for bedrooms separate from kitchens.62 Unclear spatial differentiation of functions was taken as a sign of primitivism or a lack of humanity. The MOH was careful to point out that his list of minimum accommodation was not only necessary for standards of health and moral decency but also for ‘culture.’ For the MOH of Cape Town, the slums and their density of people were not adding up to the vision of what a home, with all its satisfying Englishness, necessarily was. It is crucial to understand that the MOH’s minimum spatial requirements for a dwelling were also necessarily part of the vision of what it meant to live a proper life. Furthermore, every activity needed to be given a name, and every named activity needed to be given a space, and every activity-named space needed to be separate from the next. Of course certain activities were expected to take place within the same space – the inclusion of these largely determined by English values of the home. Clearly in Other-spaces such as the slums, just the opposite occurred. For example, in Old Cape Town, the lack of properly defined open space or gardens for children to play in was a concern (Figure 5.2). Streets, and other open spaces in the ‘slums’ were seen as inadequate and dangerous:

In Wells Square we saw a row of single-storeyed dwellings crowded with children of all shades of colours. Within eight feet of the nearest dwelling citywards ordure and bedding from an adjoining stable lay drying in the sun, and round and in this the poor little outcasts played.63

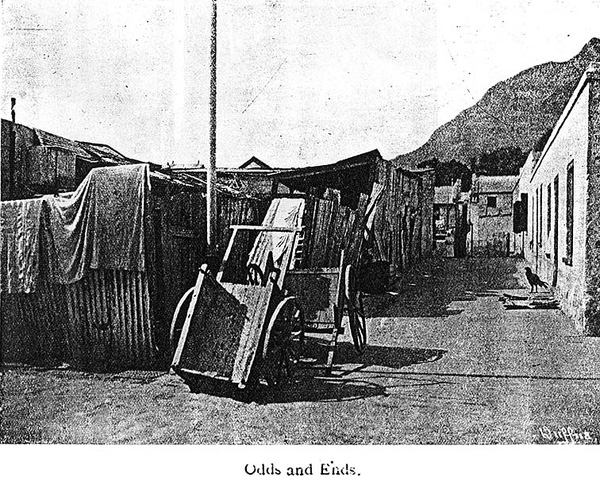

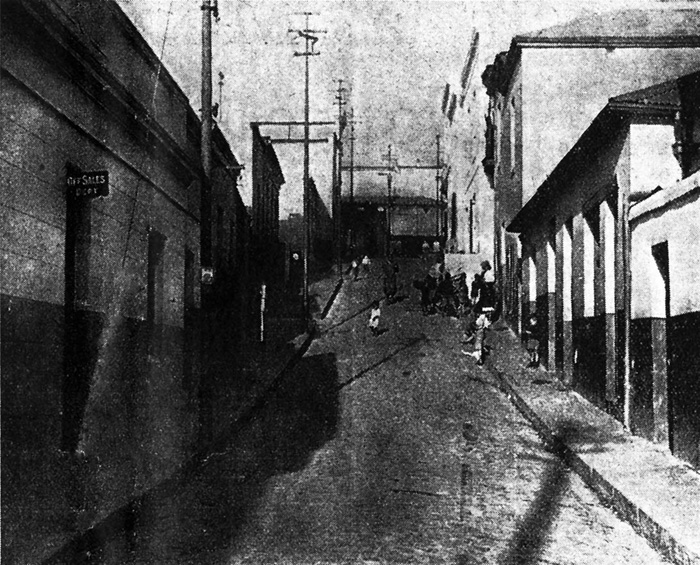

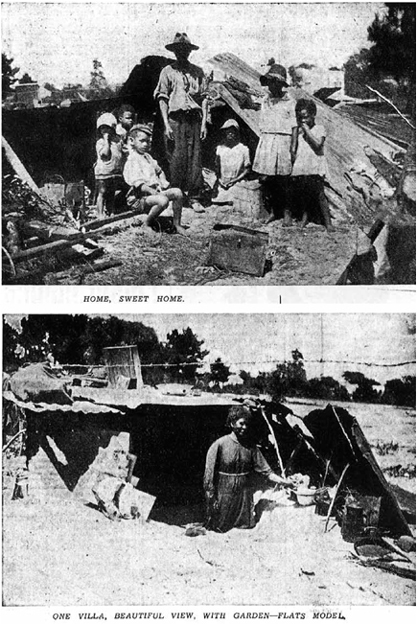

It is quite clear that the author considered this area as wholly inadequate a place in which to raise children. Children often occur in photographs of slum areas and were effective, albeit unknowing, puppets of the propaganda efforts. Whether this was from a natural curiosity on their part or whether these were perhaps staged is somewhat irrelevant. Their frequency of use in images was undoubtedly part of an editorial understanding of the potency they held. The power of the image in general was well understood and used regularly in articles on the slums. Negative judgements were cast by the use of these photographs and associated captions which expressed the inadequacy of what the object was being likened to – usually a sarcastic accompaniment to a clear intrusion into the lives of the less fortunate. Nearly always the caption reflects the viewer back to themselves through reference to middle-class values. The reader simultaneously sees themselves and the objectified subject and is appalled and repulsed (Figures 5.2–5.3).

Whether through poverty, convenience or cultural tradition, Old Cape Town was a space of much fluidity in use. In particular, one of the problems associated with its development and densification was the creation, or rather finding, of dwelling space previously used for other functions or the problem of former houses being taken over and used in a way offensive to the ‘ghosts’ of the nuclear family members who had lived there. The ‘Princess Alice in Slumland’ quote at the beginning of this chapter is an obvious example. It points to the sense of a loss of Self, where history is being erased under the ‘barbarism’ of Africa.

Awareness of this fluidity in the use and misuse of space was noted in a Cape Times tour of a shebeen:

5.2 ‘The Hungry Children of District Six’

Our objective was a three-roomed house which has been purchased by natives. We found it full of natives and coloured folk, several of them in advanced states of intoxication. In the front room I counted nine native ‘bloods’ and two coloured women, one of them a bawdy creature openly practising her filthy avocations. The place stank of sour liquor. There was scarcely an unoccupied inch of space in all the rest of the house. The passage was thronged with other natives. In the kitchen a semi-nude black man, probably doped, lay propped against the wall, his wide-open eyes full of a merciful oblivion.64

This idea of the misuse of space also included those buildings that had never been intended to be used as dwellings but were being lived in. A lot of the sensationalism in the press was based on searching for, and discovering, these buildings:

It has been common knowledge, or should have been, that for a long while past a stable loft, a converted stable, an underground cellar, a passage in a crowded house, and a backyard building have sheltered the very poor. This describes what a lady worker said two years ago: Off —– Street is a kraal, in which there are several houses and a stable (not too large), but containing about 8 or 10 horses, etc. On the stable ground is a rickety ladder, the top end resting against a very shallow loft, very much neglected and dirty. The air is impure and made worse from stable refuse, etc. In this loft, which has no door, live several girls and men of a questionable type (all coloured). One table, and some smaller boxes which serve as tables and chairs, are spread about the loft. Three of four mattresses are on the floor with bedclothes of all descriptions. A fire is burning over which two little saucepans are cooking. On this particular morning, two girls were seen sitting on the floor smoking cigarettes. They were half dressed. One’s face and head was bandaged, the result of a fight. In the farther end lies the object of the nurse’s visit – a female (young, unmarried, but living with a man), in the last stages of consumption.65

Sensationalist writing such as this was not uncommon in the newspapers reporting on the otherworldliness of Cape Town’s slums. The headings of the many series construct a sense of entering another world, vividly mapping for middle-class readers the sordid world of the Other and menacing them with the dangers of its teeming impropriety. Many alluded to the sense of voyeurism suggested in the articles, for example ‘The Opium Dens of District Six.’66 As we’ve noted, a dwelling was likely to be considered a slum simply on account of it looking like one. But what if a stable had hidden away within it a group of ‘questionable’ types? What if a reasonable façade hid beyond its decorous walls a ‘hotbed of horrors’?

MAPPING THE INTERIOR AND THE PERIPHERY

Along with the realization that the home, or the house, was no longer a representation of what functions or activities were contained therein, came the call – exemplified by newspapers such as the Cape Argus after the ’flu epidemic of 1918 – to map out the internal territories of slum dwellings:

There is only one way to prevent such things and that is constant vigilance. The city should continue to be mapped out, into the districts as they are now being worked. Serious workers should be permanently allotted to each district. Their visitations should be searching and severe. They should be acquainted with the insides of all houses, not merely the back yards. They should bring to light all cases of overcrowding, dirtiness, and disease, and they should make such an outcry about it that the authorities would be compelled to take steps to provide accommodation for the overcrowded, and to remove them; to insist on certain standards of cleanliness.67

The Housing Act of 1920 required that municipalities begin a major survey of the housing stock, which also involved mapping out the interior space of homes. The housing shortage was only part of the impetus. Obviously the state was interested in the way people were living their lives beyond the façades of their dwellings – it was by these means that it could control and manage the lives of those who were not White and middle-class, a topic taken up in more detail in the following chapter.

The condition of sight and seeing was one of the fundamental problems that was noted in the space of Old Cape Town. Aside from the problems of back yards being hidden from view, and thus potentially beyond control, there were a number of areas in Old Cape Town that were made of dense, fractured and irregular spaces, which were difficult to map out and control, and which were largely the result of laissez faire development during the British occupation of the Cape. Wells Square was the epitome of this kind of space, with its hidden interior and a permeability fundamentally threatening to not only the police, but the general public.68 Most of the illicit activities associated with Wells Square were attributed directly to the characteristics of its spatial structure which enabled activities such as gambling, prostitution, and illegal drinking.

The following stands as an example of the anxiety that the dense and hidden spaces of Old Cape Town generated:

Around the corner of a street, in a narrow passage, anywhere out of sight, we find large numbers of men, youngsters and even children divided into groups of circles, frantically busy gambling.69

It was not only Old Cape Town that began to be mapped. The increasing presence of Natives at the periphery was also noted, though it did not lead directly to the kind of extensive mapping of that had been undertaken in Old Cape Town. The Lansdowne and District Civic Association complained to the Town Clerk that ‘many natives of a very undesirable Class are squatting, on Outlands, Balmoral Estate and other parts of Lansdowne.’70 The Medical Officer of Health reported in 1923 that there were some three hundred unauthorized huts and dwellings between Muizenberg and the boundary with Wynberg which were mixed in racial occupation between Coloured, Natives and Whites.71

The awareness of these ‘problems’ at the periphery of the city was not new: similar concerns were voiced in 1900 during the Commission on a Native Location for Cape Town. The evidence at the commission also illustrates that the problems of sight/seeing were at the heart of a spatial paradox that was to haunt those in charge of the planned and future administration of the racial segregation of the city. The City Engineer admitted that Natives were living on the slopes of Table Mountain above the city: ‘I do not know whether it is a fact – that natives are allowed up in the bush to put up wattle and daub places and live there without any control whatsoever. I have seen two of these places where they live … I believe it is there men who are out of sight, and who have nobody to look after them, get drunk.’72 If the visible presence of Natives in the city was threatening (as we shall see in Chapter 7), then their non-visible presence was equally so.

In the paranoid structuring of the city as a White space, Natives and Others needed always to be seen but never in sight.

CONCLUSION

The relationship between naming and dwelling was part of the process whereby the agents of Empire were able to ascribe and lock in the Otherness of the general non-white population. It meant the urban poor were simultaneously seen as sub-human and threatening. On finding the dense living conditions of Old Cape Town the agents of Empire and jobbing journalists considered this a natural characteristic of the people living there. So the forces and interests reordering Cape Town’s domestic space with the implementation of housing schemes and Native locations, could marshal these sentiments in the rationale for the removal of Others from the city, while defining the needs of those subjects of removal as less-than that of their White counterparts. Assigning Otherness to those at the Cape who were not White and middle class bolstered a boundary-setting White identity able to take much self-assurance in its role as protector and guardian of the not quite human.

5.3 ‘Miserable Pondokkies of Cape Flats’ – informal housing at the periphery of the city

Investigations into the slums uncovered conditions thought to be a direct threat to Western civilization. The proximity of the middle-class home to the slums, although geographically very distant, was intimate thanks to the passage of servants circulating in the domestic economy of the home. Another concern was the fact that the dense, heterogeneous character of the slums permitted miscegenation and the breaking down of both literal and figurative barriers between the Self and the Other. Another major threat was the potential break down in social order as suggested through the ‘immoral’ conditions of spatial overcrowding. Furthermore, the ‘incorrect’ use of space according to its intended function not only defined those dwelling in it as bereft of rationality but led to the call for the mapping out of the interior of these spaces so that the lives of those Others could be better managed and controlled. Finally, those problematic dwellings at the periphery were pleasantly ‘out-of-sight’ but not quite ‘out-of-mind,’ as there was a disturbing sense of the need to bring these spaces under the control of the city. Whilst this chapter dealt with the really existing domestic space of Cape Town as represented through the imaginings of the agents of Empire, the following chapter considers what they thought ought to ideally (and not so ideally) take its place. Reordering the Other as the Same was beginning to be defined.

NOTES

1 Cape Times 31 July1929: ‘Princess Alice in Slumland.’

2 Duckworth, G., ‘The Making of a Slum,’ in Garden Cities and Town Planning, vol. xviii, no. 4, (April–May, 1927).

3 Cape Times 13 February 1922: ‘A Terrible Indictment;’ Cape Times 15 February 1922: Letter titled ‘The Dry Docks;’ Cape Times 22 June 1936, ‘Squalor of Peninsula Slum Quarters.’

4 African Architect, vol. 1, no. 6, (November, 1912), ‘Johannesburg’s Magnificent Contrasts;’ Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 1, no. 3 (October, 1917).

5 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/9/1/1/9: Housing Committee, 19 February 1925, petition from residents of the Lansdowne District.

6 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/4/469: Housing Committee Conferences & Letters, 24 April 1925, comment by the Mayor.

7 Union Government 34-14: Report of the Tuberculosis Commission, p.126.

8 An Indonesian word originally used to describe the reed huts of slaves at the Cape, see Silva, P. (ed.), A Dictionary of South African English on Historical Principles, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

9 The modern reader may be surprised by this direct association, but it is one that is verified in the primary sources I have looked at and also in the 1933 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, which gives the first definition of ‘hovel’ as: ‘An open shed; an outhouse used as a shelter for cattle.’

10 Easton, J., Four Questions of the Day.

11 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 1, no. 3, (October, 1917), pp.59–61.

12 Cape Times 15 February 1922: ‘The Underworld of Cape Town.’

13 Cape Times 1 November 1918: ‘The City’s Housing Problem.’

14 Cape Times 7 August 1939: ‘Pondokkie Dwellers – City’s “Sub-human” Race – Squalor and Death on Cape Flats.’

15 KAB NA457: CNL, interlocutors to Rev. Elijah Mdolomba (Weslayan Missionary).

16 KAB NA457: CNL, Joseph Corben, (Sanitary Superintendent).

17 KAB NA457: CNL, Robert Wynne-Roberts, (City Engineer).

18 Cape Times 8 December 1917: ‘Future of Wells Square.’ Quoting Rev. A. Hodges.

19 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 19, no. 5, (December, 1935): ‘The Slum Problem.’

20 As cited in Union Government 4-1920, Report of the Housing Committee.

21 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/3/97(31/3): Improvements to Wells Square 1915–1918, letter dated 18 May 1917.

22 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/4/469: Conference between the Central Housing Board and the Housing & Estates Committee, 23 April 1925 and 24 April 1925, p.9.

23 Cape Times, 14 February 1922: ‘Underworld of Cape Town.’ Letter to the Editor from ‘One Who Knows.’

24 Hawkins, A., ‘The Discovery of Rural England.’

25 Union Government Central Housing Board Report: 31 December, 1935, p.10.

26 Ibid., p.6.

27 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 10, no. 8, (March, 1927), p.22.

28 Cape Times 13 August 1929: ‘Princess Alice on the Slums.’

29 Dr Malan (Minister of the Interior and Education) at the opening of ‘Housing Week’ as reported in Cape Times 13 August 1929: ‘Menace of the City’s Slums.’

30 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 18, no. 5, (December, 1934): ‘World’s War on Slums.’

31 Cape Times 13 October 1919: ‘Site Values Rating Question.’ Paraphrasing Mr C.H. Lamb speaking at a meeting at the Red Triangle Club chaired by the Mayor: ‘The birth-rate was falling and they found that Cape Town, which had so many open spaces in its immediate vicinity, was surrounded by a belt of slums which were a disgrace to our civilisation.’

32 KAB NA457: CNL, Dr Jane Waterston.

33 Cape Times 22 June 1936: ‘Squalor of Peninsula Slum Quarters.’

34 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 22, no. 1, (September, 1938).

35 Cape Times 7 February 1922: ‘A Tour of the Shebeens.’

36 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 1, no. 3, (October, 1917): ‘A Hotbed of Horrors.’

37 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/3/97 (31/3): Improvements to Wells Square 1915–1918, reference dated 18 May 1917 to the Municipal Reform Association’s visit to Wells Square.

38 F.A. Saunders, ‘Municipal Control of Locations,’ paper read at the Thirteenth Session of the Association of Municipal Corporations of the Cape Province, held at Grahamstown, 10, 11 and 12 May 1920, p.2.

39 Cape Times 1 November 1934: ‘Building Over 120 Years Old.’

40 Cape Argus 26 October 1918: ‘The Home.’

41 Cape Times 7 May 1923: editorial. Typically this would have been a reference to strong alcohol.

42 Cape Times 27 December 1899: editorial, ‘The Kafir Problem.’

43 Cape Times 13 February 1922: ‘A Terrible Indictment.’

44 KAB CCC Mayors Minute, 8 September 1932, Appendix 6: Housing Survey, Interim Report, p.4.

45 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 19, no. 5, (December, 1935): ‘The Slum Problem.’

46 Cape Times 3 August 1929: ‘Degrading Effects of the Slum.’

47 Cape Times 1 August 1929: ‘Nationalist M.L.A.’s Indictment.’

48 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 13, no. 12, (July, 1930), pp.25–6.

49 Ibid.

50 Rheinallt-Jones, J.D. and Saffrey, A.L., Social and Economic Conditions of Native Life in the Union of South Africa. Findings of the Native Economic Commission, 1930–1932. Collated and Summarized, (Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Press, 1933); Marais, J.S., The Cape Coloured People, 1652-1937, (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1939), p.282.

51 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 19, no. 5, (December, 1935): ‘The Slum Problem.’

52 Rheinallt-Jones, J.D. and Saffrey, A L., Social and Economic Conditions of Native Life in the Union of South Africa, p.75.

53 Union Government 4-1920: Report of the Housing Committee.

54 Although many ‘coloureds’ as former slaves had inherited the names of their masters, the names considered here are particularly not Afrikaans nor Dutch in origin which suggests they were perhaps recent European immigrants. Consider, for example, the names listed on the valuation report for Wells Square prepared in 1918 as found in KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/3/97 and those contained in a petition in 1915 to the Town Clerk as found in KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/3/97 (31/3): Improvements to Wells Square 1915–1918.

55 Cape Times 20 May 1911: ‘Counting Heads.’

56 Cape Argus 17 January 1923: ‘Suicide of the White Race.’ Quote from a speech by Mrs Dawes, town councillor for Aliwal North, given at the Women’s Enfranchisement League Conference.

57 Cape Times 7 February 1922: ‘A Tour of the Shebeens.’

58 Cape Argus 19 October 1918: ‘The Home.’

59 KAB CCC Mayors Minute, 8 September 1932, Appendix 6: Housing Survey, Interim Report, p.4 footnote.

60 Ibid., p.4.

61 Union Government4-1920: Report of the Housing Committee, p.12.

62 Daunton makes the point that it was the highly differentiated internal space of English dwellings that was unusual at the time, see Daunton, M.J., House and Home in the Victorian City. Working-Class Housing 1850–1914, (London: Edward Arnold, 1983), p.57.

63 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 1, no. 3, (October, 1917): ‘A Hotbed of Horrors.’

64 Cape Times 7 February 1922: ‘A Tour of the Shebeens.’

65 Cape Times 13 February 1922: ‘A Terrible Indictment.’

66 Cape Times 8 February 1922: ‘The Opium Dens of District Six.’

67 Cape Argus 19 October 1918: ‘The Home.’

68 For a similar reading of London’s slums see Evans, R., ‘Rookeries and Model Dwellings: English Housing Reform and the Moralities of Private Space.’

69 Loubser, A.G.H., De Achterbuurten van Kaapstad, (Stellenbosch: Pro Ecclesia-Drukkerij, 1921), p.31. Author’s translation.

70 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/2/1/3/103 (5465): Unauthorized Structures.

71 KAB CCC 3/CT-4/1/5/1248 (N75/5): Natives, Alleged Squatting of: Kensington Estate, Maitland, Retreat, Muizenberg, Kalk Bay, 1922-1923, letter from Shadick Higgins to Town Clerk dated 31 October 1923.

72 KAB NA457: CNL, Robert Wynne-Roberts (City Engineer).