Bandar Abbas, Iran

The term bandar in Farsi/Persian means ‘port’, and indeed the geographical location of Bandar Abbas right on the southern coast of Iran has been its defining character ever since a settlement was founded at some point around 600BC. Positioned strategically on the narrow Strait of Hormuz, the channel of water just 54km wide which separates the Persian Gulf from the Gulf of Oman, Bandar Abbas became the main port city of the great Safavid Empire in the 17th century. Symbolically, it guards the entrance to the Persian Gulf, gazing directly over the Musandam Peninsula in Oman on the other side. Today it remains Iran’s most important port and is home to its naval headquarters. Bandar Abbas is also the capital and largest city of Iran’s Hormozgan province. However, now that the city’s population has risen significantly – it was recorded at around 367,500 people in the 2006 census, and current estimates also suggest a similar amount – urban expansion is drawing even more people in from rural areas, and slums are becoming rife. The city is expanding inland towards the north, building ever more high-rise blocks to deal with its swelling population. Along its historic shoreline, which forms the southern edge of the city, new coastal developments are also radically changing the urban skyline. With urbanisation and port activities lying behind this rapid change, what might be seen as offering a coherent contemporary cultural identity for Bandar Abbas?

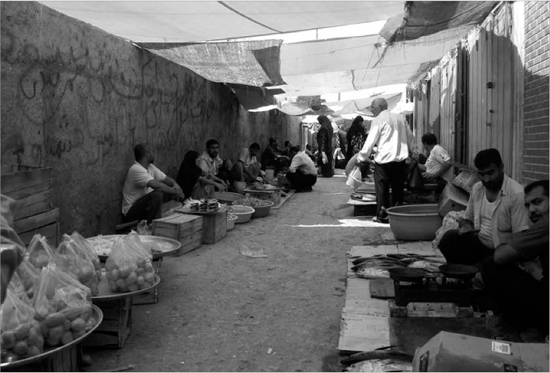

As a city, Bandar Abbas exists primarily as a major shipping node, and as such has a very long history of trade via the Indian Ocean with India and East Africa. For the traveller Ibn Battuta in around 1347, it was a fine city filled with busy markets; to the Europeans who visited Bandar Abbas in the 1400s, then known as Hormuz, it was a ‘vast emporium of the world’; while to the Chinese admiral, Ma Huan, it was the best managed port anywhere around the Indian Ocean.1 Today, it remains the most important port in Iran, and its bazaars are replenished daily with fresh sea produce as well as the imported goods that are channelled through neighbouring islands. On top of this, and because of its strategic location on the Persian Gulf, Bandar Abbas has been a major naval base ever since Iran moved its headquarters here in 1977 from Khorramshahr at the northern end of the Gulf. Economically, the major industries in Bandar Abbas include fish processing, cotton milling, textile manufacturing, steel making and aluminium smelting/refining. It is also the export centre for the outputs from the chromium, red oxide, sulphur and salt mines located just outside the city.2

At an average altitude of only 9 metres above sea level, Bandar Abbas sits primarily on level ground. Expansion to the city has been mostly along its seafront, resulting in a long and narrow city with major boulevards running in an east-west direction. Nearby elevated points are Mount Geno and Mount Pooladi, each just less than 20 km to the north. As noted, recent urban development in Bandar Abbas has tended to be towards the hillier northern areas of the city. Here, a series of modern multi-storey housing blocks are being rapidly erected next to the Shaheed Rajaee freeway, which acts at the moment as a peripheral ring-road. Some 250 km to the north of the city, a natural pass through the Payeh Mountains facilitates transport via roads to Sirjan and the rest of Iran. Climate-wise, Bandar Abbas is hot and humid with a summer period that lasts for nine months of the year. Maximum temperatures in the summer reach up to 39©C, while the winter is much milder, dropping to only 12©C. This cool winter climate makes Bandar Abbas a busy domestic tourist destination during the festival of Nowruz (Iranian New Year) in March each year.

Public spaces play a major part in the life of Bandar Abbas and in shaping the ways in which its inhabitants, coming from their different communities, are able to use and ultimately view the city. Most of its inhabitants seem nostalgic for quieter times and for glimpses of an older identity that inherently belonged to Bandar Abbas in the past, and which still can be seen in various pockets within its urban fabric. This chapter, however, will focus on the external factors affecting daily life in a city that is now experiencing the beginnings of globalisation, with its resultant influx of people from the surrounding countryside.

BANDAR ABBAS: TRADE, TRANSPORT AND TOURISM

As mentioned, economic growth in Bandar Abbas is heavily reliant on its busy port activities – especially from the flourishing flow of trade between Iran and the United Arab Emirates – as well as good transport links on land to the rest of Iran. Also key are the increased levels of domestic tourism.

In terms of trade, the nearby islands of Qeshm and Kish play a major role as points of entry for goods arriving on ships across the Strait of Hormuz (as well as acting as important tourist destinations themselves). Back in September 2003 the Iranian Parliament approved special acts which declared Qeshm and Kish Islands as ‘free trade zones’, thus liberalising trade and attracting foreign investment. In Kish, for instance, fully overseas-owned firms can now set up their operations, while visitors don’t require Iranian entry visas. In addition to this broad-brush initiative for Qeshm and Kish, various ‘special economic zones’ have been created in the two islands with the sole purpose of promoting the transit and re-exportation of goods without being subjected to normal customs duties and tax regulations.3 The port of Shaheed Rajaee, lying some 20 km west of Bandar Abbas, has likewise been declared as an ‘special economic zone’, and it now handles much of the exportation of Iranian goods. This trading flow in Hormozgan province adds up to a considerable amount given that Iran as a whole in 2003 imported goods to the value of US $22.3 billion and in return exported US $27.4 billion worth.4 Today these figures are far higher.

Beyond Kish and Qeshm Islands, and just across the Persian Gulf, are of course the Sultanate of Oman and the United Arab Emirates. With Dubai and Abu Dhabi already established as well-connected regional transport hubs, Bandar Abbas is thus in an excellent position to provide cheap land and labour to supplement the growth of those two UAE cities. According to the 2007 International Monetary Fund report on Iran, an estimated 750,000 Iranians enter this labour market each year. With the rates in Iran for skilled and unskilled labourers, and for supervisory foremen, being just half that in the Jebel Ali and Sharjah ‘free trade zones’ in the UAE, industry in Bandar Abbas is unsurprisingly beginning to see major growth. Furthermore, when it comes to the internal transport infrastructure within Iran, which already has good connections to other countries in central Asia, a draft agreement in 2006 to create the Trans-Asian Railway, nicknamed the ‘Iron Silk Road’, and linking northern Europe to southern Asia through Bandar Abbas, should in time provide even better export potential, even if progress so far has been slow.5 This new rail corridor is intended to compete with existing ship traffic passing through the Suez Canal.

Tourism is another major opportunity. Kish Island’s unique coral features and Qeshm’s natural attractions, coupled with its historic architecture, make both of them very popular destinations for Iranian holidaymakers. As a result, the amount of tourist traffic passing through Bandar Abbas has increased, even if the city itself only serves as a base from which domestic tourists can sail to the two islands by boat. However, because of the region’s harsh climate, the tourist season generally happens outside of the long hot nine-month summer. This turns parts of Bandar Abbas which are full to capacity during the busy tourist season into under-used, or often empty, areas for much of the year. The most notable locations are the public seafront spaces that, while packed out for the Nowruz celebrations, are far quieter at other times. Plus there are other detractions from the potential for tourist development. With the natural features of the islands of Qeshm and Kish offering the main attraction for eco-tourism, the alarmingly high degree of water pollution in the Persian Gulf is a real threat. The possible causes and implications of this will be discussed again later.

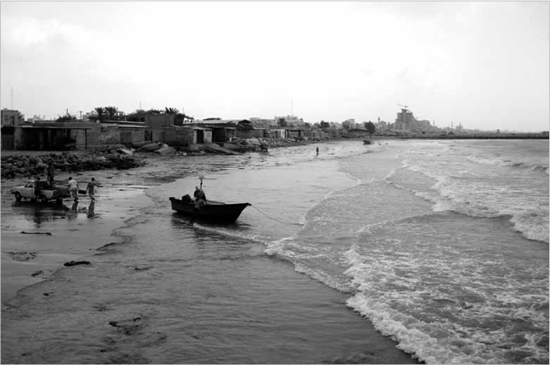

15.1 Boats taking visitors to nearby islands during the off-peak season

SLUMS AND SMUGGLING

A substantial channel for smuggling in the Persian Gulf currently passes through Kish Island, given that ‘export processing zone’ duty exemptions are available and are often used to disguise other kinds of imports leaving or entering Iran. The estimated value of illegal imports varies from US $3–8 billion a year. In addition to the smuggling of goods, reports of illegal immigration into Oman and the United Arab Emirates via Bandar Abbas are not uncommon. With the journey time between Bandar Abbas and Ras Al-Khaimah in the UAE being just two hours by speedboat, or else the chance to sail the shorter route to the Musandam Peninsula in Oman and then travel overland into Dubai, this covert movement of people should perhaps not be unexpected.6 All of these patterns of unauthorised trade and migration via Bandar Abbas is being further fuelled by an influx of people who move to the city seeking work, yet instead find themselves in poverty. As a result, Bandar Abbas now acts either as a refuge where hopeful migrants go to in hope of escaping drought and hardship, or else a temporary transit point for people and goods heading to their final destinations by whatever means possible. The consequence is that various new communities in Bandar Abbas are not fully integrated into the city and often have to live in squalid, hastily erected homes.

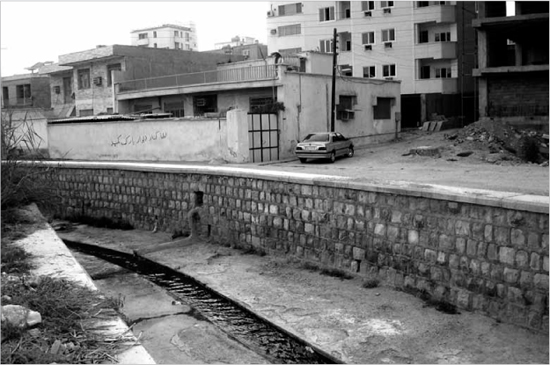

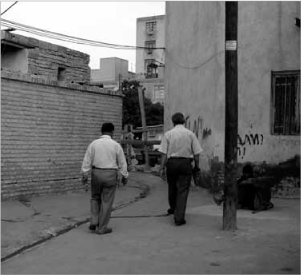

15.2 Slum areas in the northern part of Bandar Abbas

15.3 Slums along the coast providing shelter for migrant fishing communities

15.4 Waste-water drainage from slum housing

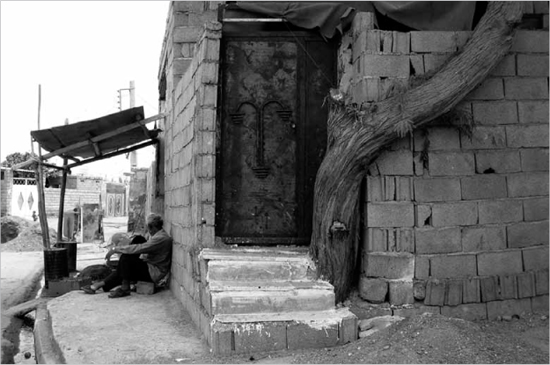

15.5 A local seller transporting his produce to the bazaar

15.6 Typical public space found under a shaded canopy in a slum area of Bandar Abbas

With busy factories and decent employment prospects for both skilled and unskilled labour forces, rural migration has hence resulted in plentiful informal settlements around the city. Most of these slums remain poorly maintained and serviced, although Bandar Abbas Municipality has partly been successful in providing proper services to these areas. Some slums are found in southern areas of the city close to the seafront, where inhabitants catch and sell fish to provide income for their families. Other slums are located north of the city centre in districts where sanitation is often highly problematic. Outbreaks of illness due to contaminated water supplies are not uncommon in Bandar Abbas. However, a network of large open drains have now been built in an attempt to facilitate the removal of sewage and waste water from dwellings, but this isn’t without its own problems as the untreated waste is simply discharged directly into the Gulf, causing concern over rising sea pollution. The occurrence of ‘red tide’, a phenomenon whereby freshwater algae rapidly accumulate in the sea and result in high mortality rates for marine wildlife, can be seen to occur in waters off Bandar Abbas. The cause of ‘red tide’ has been attributed to industrial pollutants, the dumping of urban sewage into the open sea, and systematic increases in seawater temperature due to global warming. As reported in Iran Daily on 5th August 2009, the Persian Gulf and Oman Sea Research Centre is currently monitoring the situation closely. It would appear their greatest concern is to prevent the effects of ‘red tide’ as otherwise it so directly harms the livelihoods of local fishing communities and also eco-tourism to Qeshm and Kish Islands.

Another reason for the growing numbers of people migrating into Bandar Abbas has been the severe drought conditions often being experienced in Iran in recent years. A widespread failure of rain-dependent grain crops occurred in 2008–2009, resulting in what the US-based Foreign Agricultural Service described as one of the worst droughts in recent history.7 Therefore many previously agriculturally-based communities are now choosing to resettle themselves in Bandar Abbas, where the buying and reselling of imported food produce as part of ongoing Gulf trade is seen as a more viable option to growing foodstuffs oneself in such difficult climatic conditions.

PUBLIC SPACE IN BANDAR ABBAS

The increase in population, plus the fact it consists essentially of such poor people, is putting real pressure on public space within the city. The urban layout in the slum areas of Bandar Abbas consists of small winding roads with continuous walled-in houses. These homes are generally self-built and erected without any building permission, often using the large breeze blocks found on major construction sites. Such dwellings are often then added onto as and when required, again without official permission. Houses tend thus to be grouped together according to the township that its inhabitants originated from (for example, much of the large community in the north of the city originally came from Chahestania). This then means that this migrant population remains very much as outsiders to the city they are now living in. Some steps are being taken to help the situation. The Iranian Housing and Urban Development Organization, sponsored by the World Bank, is undertaking building projects to help the integration of migrant communities with the rest of the inhabitants of Bandar Abbas. The projects include the provision of schools, cultural centres, green spaces and new roads within those communities. However, while the plentiful public spaces that have been created might seem to allow greater intermingling between newer and more established inhabitants, many of the newcomers clearly still prefer to remain close to their homes amongst their own communities. One possible reason for this may be that the majority of the new public spaces are concentrated along the waterfront, and well away from many of the socially fragmented residential areas to the north of the city.

15.7 Typical new public space concentrated along the waterfront

Indeed, public space in Bandar Abbas today largely consists of the parks and promenades along the southern waterfront. Used primarily in the evenings, all year round, these coastal spaces provide ample capacity for a wide range of activities. For most of the year, the warm evening breeze from the sea offers a welcome change from the sweltering heat of the busy bazaars during the day. The new Dowlat and Mellat Park, a 2 km-long strip situated in the east of the city, provides sports grounds and leisure facilities such as the covered picnic areas which have become a common feature along the shoreline. Since it is now the largest park in Bandar Abbas, yet at some distance from the city centre, a bus terminal has been built to facilitate transport. However, its location so far from the heart of the city means that only local residents or wealthier citizens with cars are really able to utilise the park. Smaller parks closer to the city centre, such as Bustaneh Kish Park and Lavan Park, tend to be more frequented despite the fact they are much smaller and less picturesque, and are not helped by noise from passing traffic. These smaller, brightly-lit spaces are used equally by people going out for evening walks, or by groups who sit smoking ghalyun water pipes on concrete plinths, or those who use the purpose-built exercise machines. Nonetheless, social interaction also tends to be minimal in these parks, given that the kinds of activities taking place don’t automatically lend themselves to the mixing of different groups.

15.8 Bustling public space in the centre of Bandar Abbas

Users of the parks in Bandar Abbas are likely to be a combination of tourists and local inhabitants, as well as homeless people, all of whom come for different reasons. This mixed user base also results in an assortment of architectural typologies. For instance, for the tourist in Dowlat and Mellat Park, there is an array of Iranian wind-catchers erected as historical examples from different provinces, as well as a water cistern structure which has been turned into a restaurant. These elements provide backdrops for holiday snaps along the seafront. For local residents there are smaller, less conspicuous picnic huts, and large plinths to sit upon, again mostly located closer to the water so as to provide places for human spectacle. Here the physical space of the plinths suggests an external version of traditional domestic courtyards. Firstly, barriers of light provide a level of privacy for those perched on these small concrete ‘islands’. Secondly, given that the coastal walkway paths rarely lead to these plinths, potential ‘intruders’ from outside would need to walk either along the sand or across uneven rocky ground to reach them. Thus for local Bandar Abbas inhabitants, these are perfect places they can go where they won’t be seen by others.

15.9 Open-air exercise machines in a park at night

15.10 Giant television screen for park users

15.11 Local residents smoking water pipes along the shore

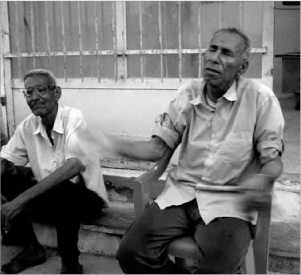

These features of constructed public space are likewise reflective of the small pockets of daily street activity found within urban neighbourhoods (see Plate 25). Often situated on street corners or beneath some form of shading, the occupants and users are generally those living in the immediate area. Keen to watch over the comings and goings in their urban living space, people become more receptive to chit-chat with outsiders, such as me when I visited. One local, Ali Lashgari, who is in his mid-seventies, told me he had a particularly nostalgic view of Bandar Abbas. Noting that most buildings have been erected in the last thirty years, he said that these had replaced older and simpler types of huts where residents once lived. Earlier in his lifetime, public facilities like the Galladari bathhouse were still being utilised as part of community life; today, instead, the baths are a tourist attraction which demonstrates the traditional system for water heating from a different era – that is, not as a part of daily habits but as a novelty attraction.

15.12 Shading structures for public picnicking

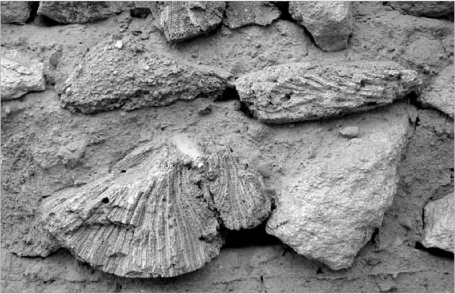

All over Bandar Abbas, the small meeting places in the streets are wedged between older buildings in the neighbourhood fabric. They are often indicated by the use of more traditional building techniques, generally based on porous sea stones, called saruuge, held in place by a mortar mixture of clay, limestone and goat hair. Today these older structures and street spaces are visually lost and often redundant among the new multi-storey apartments built of reinforced concrete and rendered breeze blocks. However, in an attempt to reclaim these lost parts of the city, there has been a strategy adopted to insert multi-purpose sport courts into residential areas. Sport, however, while it might allow the younger generation to mingle and interact, still leaves the older generation of Bandari residents to remain within their own immediate neighbourhoods.

15.13 Fishing boat passing through the breaks in the park network that give access to the water

15.14 Children’s play area with inflatable devices

15.15 Display of different wind-catchers near to the seafront picnic areas

15.16 Everyday street life within neighbourhoods

15.17 Ali Lashgari, septuagenarian local resident of Bandar Abbas

15.18 Inside the Galladari bathhouse today

15.19 Porous sea stone as a traditional building material that is no longer being used

15.20 Multi-storey apartments under construction in Bandar Abbas

BANDAR ABBAS: TRANSIT CITY

From its surface appearance at least, Bandar Abbas remains a classic transit city. More modern architectural styles are being imported and built along its waterfront to suit the purposes of economic growth, whereas traditional building approaches are now used more casually and seemingly to satisfy the general tourist demand for cultural heritage around the Persian Gulf region. While these poles represent the current trends in the architectural and cultural identity of Bandar Abbas, the segregation of public spaces from the communities that actually need them has been an ongoing problem in the city for decades. As one example, a small Hindu temple in the city centre which features prominently in tourist brochures offers indeed a novel sight within an Islamic city which is otherwise peppered with typical azure-blue mosque domes. However, the Hindu temple remains closed to the public, and can usually only be seen from outside its gates, where some local fruit sellers have set up shop. It possesses large shaded grounds of 100m2 in area, and yet these are currently cordoned off from the busy bazaar that spills over onto the pavements around, which seems a real waste. These sad remains of a building that was once so alive and yet now sits in this fenced-off section of Bandar Abbas, as with other spaces now confined solely to serving the tourist trade, help to symbolise the relics of a transient population – in this case, a past community from India.

15.21 Disused Hindu temple in the city centre

The municipality in Bandar Abbas needs to pay much more heed to this ongoing problem. Over the years, a number of transient communities have made their home in Bandar Abbas, leaving behind remnants of their inhabitation. Current migration into the city, which is being caused by rapid economic development, is also adding to the already rich ethnographical variety of people that make up its inhabitants. Therefore it is no surprise that Bandari residents always appear to be keen to assert an aesthetic which is adopted from its collective history, even if now it is primarily to attract tourists. Meanwhile the boundaries between the tourists and fleeting visitors, and those who have deeper roots in the city, remain too delineated. In terms of the traditional city residents, the new tourist attractions are kept at arm’s length, leaving those now entering the city to live and work unable to penetrate or assimilate into the local social fabric. What this suggests on the part of existing citizens is the keen awareness of – and even a resistance to – the scary prospect of being ‘colonised’ by the processes of 21st-century globalisation. Certainly many of the people I spoke to during my research voiced such worries.

15.22 A typically busy local street bazaar in Bandar Abbas

In this sense, the recent economic spurt of Bandar Abbas is in many ways detrimental for its different communities, whether older residents or newcomers. Problems caused by rampant smuggling, slum dwellings, poor sanitation and water pollution are posing real threats to people’s livelihoods and their health and well-being. The major public spaces that have been built have been designed with visitors and tourists in mind, causing local people to feel ever more marginalised; instead, the latter are now being forced into cavities of unused space within the city. That said, what the new public parks do provide are places within Bandar Abbas that are away from the crowded streets and super-busy roads. If this strategy were now to be taken further into the city, reaching into the older neighbourhoods and the new slum quarters, a series of green public spaces could perhaps help to reinforce communities that are currently being divided by powerful economic factors. With this realisation also comes the possibility of introducing renewed life back into the city centre, improving living conditions for inhabitants and revitalising its architectural character – while of course also building upon the existing delicate and multi-faceted cultural heritage of Bandar Abbas.

NOTES

1 Michael Dumper & Bruce E. Stanley, Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopaedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), p. 69.

2 Ibid., p. 70.

3 Saskia Sassen, Global Networks, Linked Cities (London: Routledge, 2002), p. 196.

4 ‘Trade and Transport Facilitation: pre-diagnostic’, World Bank website, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTTLF/Resources/Iran_pre-TTFA_04.pdf (accessed 31 August 2009).

5 ‘About the Trans-Asian Railway’, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific website, http://www.unescap.org/ttdw/index.asp?MenuName=TheTrans-AsianRailway (accessed 1 September 2009); ‘Trans-Asian Railway’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trans-Asian_Railway (accessed 20 October 2012).

6 Anna Zacharias, ‘Migrants cross strait of dreams’, 3 November 2008, The National website, http://www.thenational.ae/article/20081103/NATIONAL/336260425/1010/mcfc.co.uk (accessed 25 August 2009).

7 ‘Middle East & Central Asia: Continued Drought in 2009/10 Threatens Greater Food Grain Shortages’, United States Department of Agriculture: Foreign Agricultural Service website, http://www.pecad.fas.usdaov/highlights/2008/09/mideast_cenasia_drought/ (accessed 31 August 2009).