6

BEYOND EXPRESSION

Lily Chi

In the early 1990s, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) was commissioned to design a plan for doubling the size of the city of Hanoi. Rather than tamper with the existing fabric, the OMA proposal leaps over the Red River to establish a new district twenty-five kilometers from the city center. Hanoi New Town is an archipelago of fantastic island-districts that build on the city’s fabled relationship to water: an intriguing dreamscape and a provocative vision of cosmopolitan life as might be imagined by the author of Delirious New York.1

As victim of an Asian financial crisis, OMA’s plan was not implemented but its twin-city configuration presaged a common, if less visionary logic of development in many cities all over the world today. In Hanoi, the “36-street” district has been designated a preservation area, and plans are to remove all manufacturing and automobiles from this market quarter; in their place, boutiques selling the city’s culture and history to international visitors, and on the expanding peripheries, corporate parks, gated communities, and leisure compounds. This is a common pattern of development in so-called “new markets” all over the world as governments open their economies and resources to global finance, and their histories to leisure industries and corporate branding.

Understandably, global capital’s apparent alternatives of “museum city” and “generic city” are not universally embraced, and there is widespread, resurgent interest in Regionalism in various forms. Far from the nuanced arguments of the original authors of Critical Regionalism,2 the rallying cries for architectures of “Identity, Place and Human Experience” against the homogenizing forces of globalization project great optimism through a narrow lens.3 “The time is now for an architecture of resistance,” notes one proponent, “a spirited architecture of place … that belongs to the soil within which it is sited, and which belongs to its people too.”4 Architecture can reclaim, or appropriate the local, even invent “new identities” through “careful borrowing of elements from rich architectural traditions” to create “the ‘new local.’”5 Other regionalist trends graft identity and sustainability issues, calling for place-specific architectures arising out of concern for local environmental, material, and human ecologies.

Anxieties of homogenization, ungroundedness, and cultural identification are not unique to twenty-first-century globalization, nor are critiques of Regionalism as an approach.6 As Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Dalibor Vesely and others have argued, questions about architecture’s ability to contribute to cultural location, continuity, and coherence need to be posed within a broader horizon of knowledge structures and practices that underlie and prefigure the dilemmas of the contemporary discipline.7

In the spirit of such thinking, this essay explores an underlying premise of Regionalist ambitions: the idea of architecture as expression of site. I would like to begin with context of concerns for which the specific site, or program of a building, came to be posed not as one concern amongst others in design work, but as the generative factor for formal invention. In considering the quest for legible form as a “worksite” – a paradigmatic response to a defining dilemma of modern architectural work – rather than a design intention, I will point out two critical blind spots in the navigation of this terrain and, in a postscript, touch upon what an expanded notion of site might comprise.

Provisional grounds: architecture as expression

While architects have long been concerned with conditions of site, the idea that design should create a unique expression of a particular site is a relatively recent preoccupation. Vitruvius devoted chapters of de architectura to site considerations for ensuring the health, propriety, and operative needs of cities, buildings and theaters, but discussions of appropriate ordering and ordinance fell under entirely different principles. Site figures in these latter discussions in the need to adapt such principles – symmetry, for example – to local conditions of appearance. This understanding of site persisted well into the eighteenth century in European architectural writing. Formal references and design procedures varied greatly in the course of this history, but the guiding principles of design and the discourses thereof were attuned to a different scale of context. Whether embedded in the constructive geometries by which Gothic builders literally drew out an architecture, or played out in geometric figurations that structured building in the Vitruvian tradition, design aimed at situating the local, the particular, within a more important “macro” site: the harmonically proportioned geometric universe of classical and Biblical teaching.

The idea that the designer should “adapt his Building to the Situation,” or site, was a departure of the early eighteenth century, as David Leatherbarrow noted in his study of Robert Morris.8 Even for Morris, however, this adaptation was not a matter of individuated expression, but one of differentiation guided by three descriptive tropes – variously depicted perceptual qualities associated with the proportioning and ornamentation of Vitruvius’ three Orders. The systematic elaboration of this idea was the theory of architectural character, first introduced in the French Academy and subsequently published by Germain Boffrand in 1743. Emerging from a commingling of texts on classical rhetoric and, to a lesser extent, on physiognomy, the idea that “an edifice should present a character fitting to its destination” became widely accepted in the late eighteenth century. As disseminated by Boffrand and fellow academician Jacques-François Blondel, character theory was effectively a reformulation of key Vitruvian principles – harmony, proportionality and the use of the Orders – into a theory of architectural expression. Most adherents assumed Boffrand’s premise about how “character” would be rendered in architectural terms: the Orders served as ready-made formal tropes, three genres of appearance and perceptual effect. The judicious choice and adaptation of these genres to specific sites and programs would render legible the entire range of possibilities in the eighteenth century’s changing social and urban landscape.9

The terms of character theory were, however, intrinsically open-ended. In due course, all terms in the formulation came to be rethought: from the formal basis for architectural character, to premises about the “spectator” in or of architectural works, to the very “destinations” or programs that comprised a civil society.10 In leaving behind the Vitruvian Orders as a basis for architectural character, in drawing on premises of corporeal sensing and ideation to explore entirely unprecedented formal inventions, Etienne-Louis Boullée’s projects in Essai sur l’Art perhaps comes closest to contemporary notions of design as a search for individuated expression.

Despite this divergence on what exactly constituted architectural “character,” architects converged in their anxieties. “Such is the degeneracy of fashion,” lamented Boffrand, “that at times what ought to be at the top has been placed at the bottom.”11 Boffrand’s complaints can still be heard a half-century later: “There are no certain principles in architectural composition; each architect has his esprit, his own specific way of arranging proportions… . Thus, the diverse qualities, the constitutive proportions of a beautiful building … are but arbitrary qualities?”12 Readers of Pérez-Gómez’s scholarship will recognize in Charles-François Viel’s rhetorical question the long shadow cast by Claude Perrault. If the principles of harmonic proportion that had long guided architectural invention and collective apprehension have no basis beyond custom, what then? Is architectural work left to the wiles of individual fancy and the vagaries of relativism? Boullée summarized the angst of the period in one plaintive question: “Is architecture merely fantastic art belonging to the realm of pure invention or are its basic principles derived from Nature?”13

Writers on architectural character diverged greatly on Boullée’s second question, but were resolute on the first. The significance of these varying theories of architectural character for the eighteenth century’s crisis of grounds lies not so much in the emergence of a coherent new idea of Nature, but in their very structure. The formulation that design should express the character of a building program or site effectively replaces Vitruvian tradition’s extrinsic schema of harmony – between micro and macro, between the ordinance of buildings and bodies, both heavenly and corporeal – with a more modest, intrinsic “harmony:” that between a building program or site, an architecture that gives visual expression to that program/site, and a sentient “spectator.” The space opened up between these three terms is a dialogical structure, a linguistic space: a finite, delimited public realm in which architecture acquires legibility, and creative invention and critical discourse find a local, provisional ground.14

In other words, the idea that site or program could serve as a referent for architectural form emerged in a context where premises about the grounds for architectural ideation, and concordantly, for creative invention, could no longer be assumed but must be actively sought in the work of design itself. One can see in this predicament a common thread between apparently antinomic design doctrines since the eighteenth century, from Form follows Function to the various historicist and semiotic approaches that ensued therefrom. Regionalism in its various guises is but one expression of a broader “burden” of creative invention in modern contexts: to wager and posit within the work itself the terms for its legibility and grounding.

Naturalizing expression

Defining the quest for legible, expressive form as a modern problematic – a worksite rather than a specific design intention – surfaces new sympathies between seemingly distant design methods and agendas, but also one important point of difference. For many eighteenth century architects, “taste” guided the interpretation of site and program into visual form (through proportions, geometry, figurative elements … ). Taste, in turn, was defined as consensus amongst the most “enlightened” men about the parameters for appropriate form. This explicit reliance on the opinions of men, and the ambiguous measure of appropriate – as opposed to correct – form made character theory a historically short-lived idea.

In the dawn of a new, post-Revolutionary France, Jean-Nicholas-Louis Durand’s reformulation of architectural character reflects a slightly different tack:

if one composes an edifice in a manner fitting to the usage to which one destines it, will that not perceptively differentiate it from another edifice destined for another usage? Will it not naturally have a character and, furthermore, its own character?15

With correct reasoning and method, self-evident, readable architecture automatically follows. In developing his compositional method, Durand was of course not concerned with architectural expression. Legible, expressive form is not a matter for deliberation – not a matter of choice, interpretation, or judgment – but the direct outcome of correctly applied principles and procedures. This aspiration for a method of work out of which a “natural” expression arises – one that could bypass the finitude and fallibility of human judgment and individual wills – articulates an enduring trope in modern efforts to define a theory of design without recourse to transcendent givens.

A particularly illuminating illustration of this trope in contemporary architecture is given in an early and influential argument for “morphogenesis” as a design method. For Sanford Kwinter, Lindy Roy’s “Delta Spa” project in Botswana exemplifies a “different design methodology,” one that begins with a clearing of the decks of tradition, on the one hand and of willful form-making on the other.16 Working with clear analytical parameters and computational tools, design becomes a tapping of Nature’s own volatile, dynamic forces, as exemplified by the African landscape and its peoples. Generative software is key to this mimetic aspiration: the architect does not make forms; s/he sets up processes of interaction and parameters for their unfolding. The results of the two algebraic processes that generate the work may be compared to “pheromonal wakes of termite swarms,” African space–time, African music, with each of these being alternatively understood as an “animal event,” a “dance of genesis, of life,” “African genesis in general,” “feminine forces,” the “feminine weave of temporalities,” and even “the classical Chinese tradition.” Morphogenetic design in this project aspires, in short, to the very principles of originary harmony between site, beings, and dwellings. “Site” in this case is not a physical given, not a cultural given, but the principles of emergence of both: with strategic use of computational tools, the designer may simulate nature’s own processes of form-giving – that which generates human and animal, the geological and the biological.

Such aspirations retrace a pervasive theme in nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and architecture, from the search for models in physical and biological processes to surrealist automatism: the dream-wish for the ultimate performance of authentic invention, one that could be finally free of the taint of “willfulness” and artifice, whether cultural or individual, but would nonetheless result in natural, directly signified, meaning.

Theories of Natural, machinic or automatic processes of formation have their own dilemmas, however. In the asymptote towards pure, unmediated becoming, human agency remains at work somewhere in the generative process: designing the set-up, making selections and editorial choices along the way. What role does this interpretive agent have, and to what critical criteria would that agency submit? To the extent that this question goes unanswered, such agency goes underground, sublimated by method and procedure. Premises and preconceptions sink to an unexamined subterrane. The narrative in “African Genesis,” for example, recalls a number of common tropes in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century literature in its conflation of geological formations, climatic processes, animal behaviors, and diverse cultures and peoples past and present as exemplars of Becoming, and in its romanticizing of this composite Other, Africa, into a figure of prelapsarian harmony and originary innocence. The schema of natural versus acculturated (“genetic” versus “willful”), popular in early twentieth-century art, finds its mirror image in the “savage”/“modern” or uncivilized/civilized dualism used by colonizing nations to present their economic and political agendas as “civilizing” missions. This idealization of pre-modern harmony seems benign on the surface, but in fact reiterates a framework of imagination with a dark history. In naturalizing premises about the grounds and limits of expressive/legible form, in seeking recourse from cultural constructions, opinion, or individual judgment, theories of automatic or emergent form –whether derived from rational method or a-rational procedures – risk critical blindness when such premises resurface in unexpected ways.

Instrumentalizing expression

While the specter of groundlessness remains a predicament of design work, architecture’s location in contemporary contexts compels reconsideration of the parameters by which the site of architectural work is defined.

In Enlightenment France, “speaking architecture” promised a new approach to urban and civic coherence. Whether drawing on Aristotelian notions of sympathetic comportment, or on new sensorial theories of understanding, writers on architectural character hoped to inspire virtuous conduct in the spectator. Similar aspirations towards liberatory forms of individual and collective experience characterize the early twentieth-century avant-garde’s efforts to seek out new grounds for visual expression in art and architecture. “In our architecture, as in our whole life,” wrote El Lissitsky in 1929,

we are striving to create a social order, that is to say, to raise the instinctual into consciousness… . It is not enough to be a modern man; it is necessary for the architect to possess a complete mastery of the expressive means of architecture.17

Architecture’s affect can also be useful, however, and early modern revolutionaries and social reformers recognized this potential. Jean-Baptiste Say, the economist and businessman behind the famous Law of Markets, or Say’s Law, gave architecture a formative role in his utopian fiction Olbie, ou essai sur le moyens de réformer les moeurs d’une nation (1800). Olbie was a readable moral landscape, its architecture a vehicle of instruction:

If the attentions of society towards its members were everywhere in sight, everywhere also they read their duties toward it. The language of monuments makes itself understood by all men, for it addresses itself to the heart and imagination. The monuments of the Olbiens rarely recounted purely political duties, because political duties are abstract, based more on reason than on feeling… . It was not only in the cities that monuments spoke to the people; they were also to be found in other frequented places, in the middle of promenades and along the main roads.18

Different from mid-eighteenth-century formulations of architecture as dramatic staging for virtuous comportment, Olbie’s sensible landscape operated alongside other ubiquitous forms of persuasion to cultivate internalized behaviors. For Say, who read Rousseau and Locke, Olbie was a work in time: if the father had to be taught proper morals, for the child it would become second nature.

The instrumentalization of expressive monuments is decidedly less utopian in the context of late capitalism. For corporations and city governments seeking a competitive edge in the global market, the “Bilbao Effect” –the extraordinary role played by Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim design in reversing the fortunes of a depressed industrial town – has become paradigmatic. In the experience economy, singular, novel design has emerged as a powerful instrument for generating capital and investment.19 At the same time, the common ground opened up by engaging architectures and spaces have been pressed into economic service in the form of thematized environments for consumption, or for selling. Both kinds of architectural “products,” as they are un-ironically called in the industry, aim not only at passive spectatorship but, different from the docile citizenry in Olbie, at pacified consumption – that of novelty on the one hand, and of familiarity on the other. The commodification of architecture – and by implication, of occupants, designers, builders, and workers – plays out behind the architect’s back, inscribed into frameworks and practices well beyond the designer’s worksite.

The ideal of architecture giving relevant expression and therefore coherence to a social, cultural context is complicated by other dynamics and invisibilities. Evidence points, for instance, to increasing ephemerality in everyday environments the world over – and not just that given in technology, media and consumer products. In post-industrial economies, for example, migrancy has become a permanent life experience for an increasing number of people in all walks of life: from corporate heads, to professionals, to laborers. Theorist Arjun Appadurai and others have called for new analytical terms to comprehend these trans-territorial imaginations of world and of location: it is not that physical, regional or national territories are no longer relevant but that these describe only one dimension of such imaginings.20 There are also invisibilities within this migrancy. In Hanoi, for instance, “informal” workers contribute one-sixth of the city’s gross domestic product (GDP), making up nearly half of the city’s workers. Their contribution is informal because neither their work nor their very presence is officially recognized. Rural migrant workers literally do not count as citizens of the city, even as their vital role in the city’s welfare, its maintenance, its physical nourishment and even its economics is commonly known. This is the case in much of the world’s centers of commerce, from Mumbai to Nairobi, to the fringes of North American cities.

Love of the city

What kind of potentials lay in the place in which we were standing. What can it mean to think about and design architecture beside da-me architecture?21

At the center of our research has been the fostering of an expanded modality of architectural practice.22

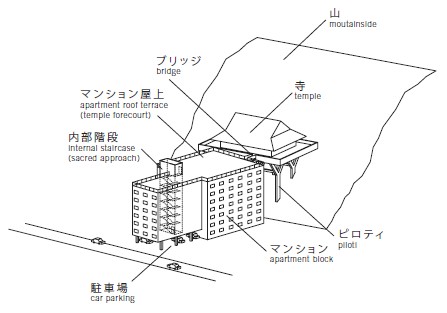

Figure 6.1 Atelier Bow-Wow, apartment mountain temple, analytical drawing from Made in Tokyo (2001); courtesy of Atelier Bow-Wow

Atelier Bow-Wow’s Made in Tokyo documents selections in what others might call a generic urbanscape: a driving school on the roof of a big box supermarket, colonnaded tennis courts inserted into the leftover center of an expressway off-ramp, a hilltop temple grafted to an apartment block… . “We decided to call these ‘da-me architecture’ (no-good architecture), with all our love and disdain,” writes Yoshiharu Tsukamoto:

Most of them are anonymous buildings, not beautiful, and not accepted in architectural culture to date… . However, if you look closely … in terms of observing the reality of Tokyo through building form, they seem to us to be better than anything designed by architects.23

Curious or no good as they may be for architects accustomed to the “self-standing completeness” of architecture as icon, these “mongrel” buildings reflect how urban coherence is experienced by city dwellers. “Everyday life is made up of traversing various buildings,” notes Tsukamoto, “living space is constituted by connections between various adjacent environmental conditions rather than by any single building.”24

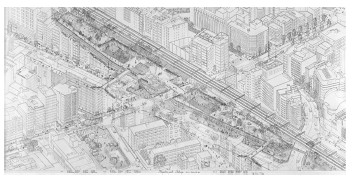

The tactics of co-location by entrepreneurial Tokyoites – spatial borrowings, parasitic adaptations and symbiotic “interlappings” of program, structure or surface – hint at the marvelous logics and spatial inventiveness hiding in plain sight in the everyday city. Indeed, examples like the Apartment Mountain Temple (Figure 6.1), wherein the staircase and flat roof in the one are the ritual ascent and forecourt in the other, testify to a more complex and agile perceptual practice – one in which form is not a static, self-identical substance, but emerges in relation to circumstance and engagement. As for the user, so for the tactical builder – the physical city is a malleable substrate for creative adaptation and improvisation. Through this and other meticulous field studies, through their multifaceted design practice, Atelier Bow-Wow reveals and engages the city as a living, dynamic, and irreducibly heterogeneous context shaped by diverse agents and agency. Speculations on “void metabolism,” “urban ecology,” “micro-public space,” or “behaviorology” are efforts to articulate these other forms of agency, and to reposition design as an engagement with latencies, with “stages in waiting” and dramas in media res (Figure 6.2).

Teddy Cruz, too, finds critical grounds and motive in the quotidian urban: in his case, the neglected suburbs and shantytowns wherein the service and factory workers of global commerce reside. Here, on the borderlands between San Diego and Tijuana, Cruz gives witness to unseen logics and formations entailed in supplying, sustaining and servicing affluent America. South of the border, American factories congregate in low-tax, and low-wage “special economic zones”; around them, expanses of informal worker settlements. On the US side, zoning regulations and finance policies literally prescribe and preform the built environment: “catch-22s” that privilege big developments and exclusionary land uses, resulting in evacuated public realms. Across this territory, a steady northward flow of goods and services belie the rhetoric of border security. A reverse flow removes the discards of American gentrification: bungalows slated for demolition to make room for luxury condominiums in San Diego head towards the shantytowns for inventive re-use.

Figure 6.2 Atelier Bow-Wow, renovation of Miyashita Park, Tokyo (2011); courtesy of Atelier Bow-Wow

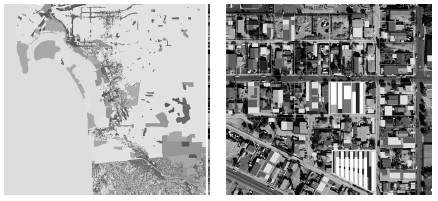

Cruz finds great creativity in these “sites of scarcity.” In Tijuana’s settlements, and in San Diego’s older first-ring suburbs where immigrants from Latin America, Africa and Asia have settled, rich and complex practices of building, adaptation, entrepreneurship and communality flourish. Well below the radar of southern California’s vast tracts of single-family zoning, for example, an “alternative zoning” has taken root: a vibrant bottom-up urbanism of parking lot social spaces, second businesses in garages, informal flea markets and street vendors in vacant lots, and a Buddhist temple in a converted bungalow. These “plug-in” programs and architectures “pixilate” the monotonous and vacant sprawl produced by traditional zoning in the area (Figures 6.3a and 6.3b).

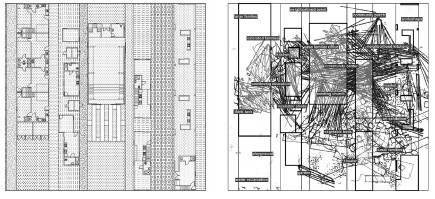

For Cruz, both the disparities produced and maintained by dominant socio-economic structures, and the informal practices of sociality and livelihood that counter them bear profound lessons for contemporary architecture. Rejecting fetishistic images of the informal, Cruz sees the tactical procedures therein as “urban operations” that, in allowing for local transgressions of imposed political and economic logics, and in offering models for rethinking conventional terms of planning and development, can initiate “trickle-up” institutional and political transformations on the whole system (Figures 6.4a and 6.4b). For Cruz, these are the springboards of truly experimental architectural and urban work:

Figure 6.3 Estudio Teddy Cruz, analysis of land use near US–Mexico border: (a) ‘pixilation’ of official zoning by informal uses in southern California (left) and (b) and in the suburb of San Ysidro (right); courtesy of Teddy Cruz

Ultimately, it does not matter whether contemporary architecture wraps itself in the latest morphogenetic membrane, pseudo-neo-classical propositions or LEED-certified photovoltaic panels if all of these approaches continue to camouflage the most pressing problems of urbanization today. As architects, we can be responsible for imagining counter-spatial procedures, political, and economic structures that can produce new modes of sociability and civic culture.25

Atelier Bow Wow and Teddy Cruz ground their practices in a love of the city – its creative intelligence, but also its invisibilities and injustices. For both, the city is a wellspring of critical provocations and creative vitality for an interest in civic architecture. Their respective projects offer two takes on an expanded concept of site, and by implication, an expanded worksite for architecture.

In drawing this discussion to a close, I would like to trace the outline of such a worksite. In this “macro” site, the technological, economic, and socio-political pre-figurations of a context would rank alongside physical and cultural location for critical inquiry. What logics and agendas are already at work in circumscribing, delimiting, or prefiguring a work of design? What is the architect’s and building’s role, complicity and effect in the movement of money, power, ideas and material resources? How might design be already instrumentalized by these contexts, and what opportunities are there for counter-construction? To that end, an expanded worksite would be nourished by research and inquiries into negative histories – or histories of anti-models – as well as histories of possibility. This, so that we can see their intertwinement, and better recognize ourselves in them.26

Figure 6.4 Estudio Teddy Cruz, Living Rooms at the Border project: (a) static plan (left), and (b) dynamic plan constructed over Barry Le Va’s 1968 drawing Three Activities (right); courtesy of Teddy Cruz

In a worksite drawn beyond formal terms, furthermore, architecture’s “agency” would emerge as a question for critical analysis and creative intervention. Design would entail deliberation on not just appropriate form, but on appropriate action and measure. In looking beyond expressive form to modalities of effect and enablement, we might come to see that there is no such thing as a “generic” city. Moreover, if architecture is technologically, economically, politically, and culturally pre-figured and disseminated in arenas beyond the building site, how could these arenas be opened to Daedalian cunning?27

Finally, while I write of contemporary challenges, I am mindful that this argument for an expanded worksite is not novel. In the opening chapter to De architectura, Vitruvius, who was not one for abstract ambitions, set out a long list of learning pertinent to architects. Beyond skill in drawing, he wrote, the architect must be knowledgeable in geometry, history, philosophy, music, medicine, jurisprudence, astronomy, and the theory of the heavens. Acknowledging the list’s expansiveness, Vitruvius insisted on an understanding of principles in these areas. Such learning is “indispensable” so that the architect may not be found wanting when “[s/]he is required to pass judgment.”

Notes

1 Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978).

2 Rem Koolhaas, “The Generic City,” Domus 791 (March 1997), 3–12.

3 Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983); and Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre, “The Grid and the Pathway,” Architecture in Greece 5 (1981).

4 Paul Brislin, “Identity, Place and Human Experience,” Architectural Design 82, no. 6 (November/December 2012): 13.

5 Farrokh Derakshani, “Appropriating, Reclaiming and Inventing Identity through Architecture,” Architectural Design 82, no. 6 (November/December 2012): 31.

6 See, for instance, Hajime Yatsuka, “Internationalism Versus Regionalism,” in At the End of the Century: One Hundred Years of Architecture, ed. Richard Koshalek and Elizabeth Smith (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1998); Alan Colquhoun, “The Concept of Regionalism,” in Postcolonial Space(s) (New York: Princeton University Press, 1997); and Keith L. Eggener, “Placing Resistance: A Critique of Critical Regionalism,” Journal of Architectural Education 55, no. 4 (May 2002).

7 Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983). See also Dalibor Vesely, “Architecture and the Conflict of Representation,” AA Files 8 (Spring 1985): 21–39; and Dalibor Vesely, Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004).

8 David Leatherbarrow, “Architecture and Situation: A Study of the Architectural Writings of Robert Morris,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 44, no. 1 (March 1985), 48–59.

9 See, for example, Jacques-François Blondel, Cours d’architecture (1771), vol. I, 373–374, 389–90, vol. II, xxv–xxvi, xli, xlv, 229–231; and Jacques-François Blondel, Discours sur la nécessité de l’étude de l’architecture (1764). See also Antoine-Chrysostôme Quatremère de Quincy’s definitions of caractère in Dictionnaire d’architecture (1788–1825) and Dictionnaire historique d’architecture (1832), and his arguments on modern architecture in Sur l’idéal dans les arts du dessin (1805), Considérations morales sur la destination des ouvrages de l’art (1815), De l’invention et de l’innovation dans les ouvrages des beaux-arts (after 1816), and his Essai sur la nature, le but et les moyens de l’imitation dans les beaux-arts (1823); and Lily Chi, “On the Use of Architecture: the Destination of Buildings Revisited,” in Chora: Intervals in the Philosophy of Architecture, ed. Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Stephen Parcell (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), vol. 2, 17–36.

10 Compare ideas of character in: Germain Boffrand, Livre d’architecture (1743); Blondel, Cours d’architecture (1771); Jean-Louis Viel de Saint-Maux, Letters sur l’architecture (1787); Étienne-Louis Boullée, Architecture, essai sur l’art; Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières, Le Génie de l’architecture (1780); and Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy, revised entry on caractère, Dictionnaire historique d’architecture (1832).

11 Germain Boffrand, Book of Architecture, trans. David Britt, ed. Caroline van Eck (Aldershot, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002), 5.

12 Charles-François Viel, Des anciennes etudes de l’architecture (Paris: 1807), 5.

13 On the specter of relativism, see also Boffrand, Livre d’architecture, 3–9; and Blondel, Cours d’architecture, vol. I, 463, on decadence see vol. III, and Discours sur la nécessité de l’étude de l’architecture. On the problem of grounds for judgment, see Quatremère de Quincy, “Architecture” in Encyclopédie méthodique (1788), Considérations morales, De l’invention et de l’innovation, De l’emploi des sujets d’histoire modern dans la poésie et de leur abus dans la peinture (1825), and Essai sur la nature.

14 Quatremère de Quincy’s lucid definition of “necessity” in Considérations morales is particularly illuminating. Reflecting upon the different ways in which two things can be said to be “necessarily” related, Quatremère concluded that the only form of necessity that can be created by mortal beings is the apparent harmony between the form of a thing, its destination, and the beholder. As in his 1932 definition of caractère, meaningful creative work is here defined not in an intrinsically universal principle, but as the result of an internal correspondence between a work and its programmatic situation – an integrity that opens up a finite, common ground for critical discussion. Meaning in the arts, in other words, rests on the accomplishment of a linguistic circuit – a language community.

15 Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, Nouveau Précis (Paris, 1813), 19.

16 Sanford Kwinter, “African Genesis,” Assemblage 36 (August 1998).

17 El Lissitsky, “Ideological superstructure,” in Programs and Manifestoes of 20th-century Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1964), 121–122.

18 Jean-Baptiste Say, Olbie, ou essai sur le moyens de réformer les moeurs d’une nation, 1800. (Paris: Deterville, Treuttel et Wurtz, 1800), 612; trans. adapted from Roy Swanson, Utopian Studies 12, no. 1 (2001): 104–105.

19 See, for example, Richard Florida’s highly influential The Rise of the Creative Class (New York: Basic Books, 2002); and Brian Lonsway, Making Leisure Work: Architecture and the Experience Economy (London: Routledge, 2009).

20 Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

21 Momoyo Kaijima, Junzo Kuroda and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto (Atelier Bow-Wow), Made in Tokyo (Tokyo: Kaijima Institute Publishing Co., Ltd, 2001).

22 Teddy Cruz, “On Returning Duchamp’s Urinal to the Bathroom,” Arquine 55 (Spring 2011): 96; the title quotes artist-performer Tania Bruguera.

23 Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, “What is Made in Tokyo?” Architectural Design 73, no. 5 (September/October 2003): 40–41.

24 Ibid., 43.

25 Cruz, “On Returning Duchamp’s Urinal,” 96.

26 The projects of nineteenth-century colonialism and nationalism, for instance, play a formative and constitutive role in some of the most prominent concepts of modern intellectual and creative history and yet these remain the most consistently repressed aspects of contemporary critical discourse. Notions of tradition as counterpoint to the modern, of the cultural Other as models of purity or primitivism, and even the concept of Regionalism find their roots in this history.

27 Alberto Pérez-Gómez, “The Myth of Daedalus,” AA Files 10 (Autumn 1985): 49–52.