British Architects in the Gulf, 1950–1980

In the July 1977 issue of Building magazine, there was a report on an RIBA conference on the Gulf States, and in the same issue readers were treated to an artist’s impression of a £3 million multi-storey tower complex in Doha, Qatar by a consortium consisting of White Young and Partners of Qatar and London, Arabian Design Associates of Doha, assisted by Hughes and Polkinghorne of Norwich.1 Leafing through the architectural magazines, particularly those of the 1970s, it is not unusual to find articles chronicling the activities of numerous British firms working in the Gulf, and it could be claimed that this work kept the architectural profession in this country afloat, especially during the recurring periods of recession in the post-war era. My intention here is to investigate the activities of British and American architects in the Gulf from the 1950s through to the late-1970s, and to ask whether the work done in this region was a feature of an incipient global market in building, or a prolongation of colonialism in what has been historically a contested location. Furthermore, has this regional building history set precedents which are difficult to discard even today?

With the break-up of the Ottoman Empire in the early decades of the 20th century, Britain and France established Mandates which were intended as temporary administrations until such time that it was deemed prudent to allow the indigenous peoples within the old Ottoman Empire to rule themselves. France took control of Lebanon and Syria, while Britain took control of Iraq, Iran and the areas around the coast of Arabia. Britain’s interest was primarily the transport route to India, but after 1912, when the Royal Navy switched from coal to oil in order to fuel its ships, the supply of oil assumed an increasing importance. Mindful of their increasing reliance on oil, in 1914 the British government bought the controlling interest in Iran’s Anglo-Persian Oil Company.2 Both Iran and Iraq resented British interference in their internal affairs, and this was especially true of Iraq, which in 1920 was not really one state, but in fact three distinct regions with little to hold them together. After an armed intervention which cost lives and money, and alienated the population further, Britain continued its control of Iraq at arm’s length – until the Second World War when it placed Iraq under military occupation.3 Iran meanwhile suffered from its strategic position between the British and the Russians. During the Second World War, Iran became a vital supply route for the Soviet Union in its fight against Nazism, and when the Shah showed pro-German leanings, the two powers invaded the country.4 Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States were able to maintain more equable relations with Britain, largely because their populations were small, plus a series of treaties with the ruling sheikhs around the Gulf ensured that Britain could maintain the required stability along the coast, and direct control of the all-important Aden Protectorate.5 Given that oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia only in 1938, the great wealth of that country became apparent only after the end of the Second World War.

Given the complex pre-war history of the Gulf countries, particularly those of Iraq and Iran, it is a wonder that British architects made any headway there at all during the 1950s. It says something for the strength of the local desire to modernise the material fabric of these countries, that western engineers and designers were encouraged. In post-war Britain itself there was the will to modernise, a task in which architects would take an active part, but in the immediate post-war years the draconian cancellation of America’s ‘Lend-Lease’ agreements in 1945, led to a crippling lack of cash for the post-war Attlee government, especially for public sector work.6 The architect Raglan Squire recounted that in the 1950s, when his practice needed a boost, he read a paper which commented on the fact that there were 22,000 fully qualified architects in England, while in the Commonwealth countries the numbers could still be counted on the fingers of one hand.7 Convinced that the opportunities overseas were immense, he opened an office in Baghdad in 1955. City plans and infrastructural schemes were undertaken by British firms, along with architectural work, and as Squire noted, the planning of Baghdad was given to Minoprio and Spencely, Basra to Max Lock, and Squire himself got Mosul – not that any of them had time to do much work on their plans before the revolution in Iraq in 1958.8 During the next administration, the Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis was given the task of producing an urban design for Baghdad. Like the English architects before, he seemed to make little distinction between the different ethnic and religious areas – and in fact his Ekistics approach was supposed to erase differences through the application of a rationalist mentality.9

It might well have been asked, besides Max Lock, how much experience the British architects had in planning large urban areas. In the March 1957 issue of Architectural Design devoted to the Middle East, Raglan Squire made the point that all the plans of these important centres were by British consultants, which he considered appropriate, since ‘it has been England who has led the world in town planning’.10 But this claim was modified by the warning that: ‘A planning consultant can find himself in the difficult position of trying to explain a plan to an audience who have little or no conception of what town planning, as it is practised in highly-developed countries, really means.’11 This clash of cultures became a leitmotif in the journals as time went on, and as the projects funded by the increasing oil revenues became ever larger and more ambitious.

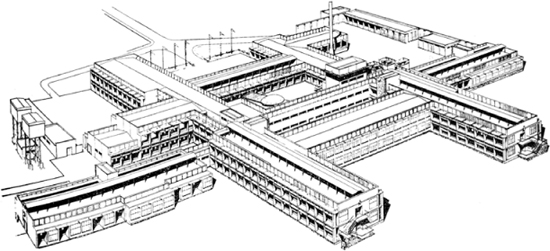

2.1 Plan of Baghdad by Minoprio and Spencely and F.W. Macfarlane

As mentioned previously, it had been important for Britain to keep the Gulf region on its side while India remained such a vital part of the Empire, but it was the discovery of oil which kept the British there after 1947. The Gulf States assumed inordinate importance to the British economy, with Kuwait in 1967 becoming the single largest foreign holder of sterling.12 Suddenly, rather poor and neglected territories in the Middle East acquired a degree of importance far beyond anything they had experienced before. Areas which had managed with almost no infrastructure up till then were transformed with roads, oil wells, refineries and desalination plants. Buildings for schools and hospitals, previously more or less unknown, were required along with commercial spaces. Not having needed these buildings before, the Gulf States had not developed a profession of designers, and therefore it was understandable that they would have to look outwards for professionals who were more expert in producing buildings of all types.

Many young British architects, fresh from architectural schools or war service, were looking for work in an overcrowded profession when suddenly competitions began to appear for work in the Gulf States. In 1952, an RIBA competition for the Doha State Hospital in Qatar was won by the young husband-and-wife team of John R. Harris and Jill Rowe, fresh graduates of the Architectural Association in London. When they won the competition, they had already worked on the Building Research Laboratories in Kuwait, but they still had to figure out from first principles how to design what was possible as well as what was appropriate.13 Their innovations extended to contract and management, so that, for example, the foundations of the Doha hospital could go ahead and be built while the London office was still producing the working drawings – thus demonstrating to the Qatari population the political point that a new hospital was immanent.14 This was just the beginning of a long association of John R. Harris Architects with the Middle East. In 1958 they produced a plan for Dubai and subsequently designed six hospitals there. They opened an office in Kuwait and also in Tehran for the work they undertook for the National Iranian Oil Company. In 1961 they produced the first development plan for Abu Dhabi, and then they went on to do work in Bahrain, Sharjah and Oman. Harris’s success came as a result of chance, since his office’s decision to enter the Doha competition had been weighed against the possibility of entering the competition for Coventry Cathedral; nonetheless, the Qatar commission also ensured that a struggling young practice survived the adverse post-war economic conditions.15

2.2 Doha State Hospital in Qatar, bird’s-eye view, by John R. Harris and Jill Rowe

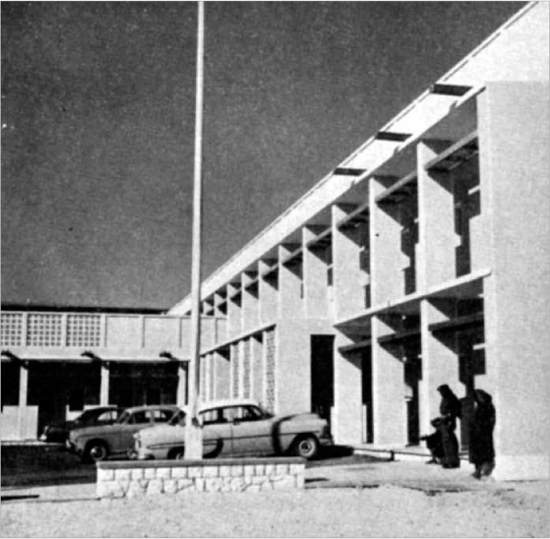

2.3 Doha State Hospital, main entrance view

Those architects who ventured into the Gulf found a building environment totally different from anything that most of them had previously encountered, with excess heat and sunlight a factor in early designs, while the procurement of materials and equipment was a perennial concern, even compared to the difficult conditions back in Britain. However, even in the 1950s there was an awareness that the issue of cultural specificity was important, although it was not always clear what this meant. In the 1957 issue of Architectural Design devoted to the Middle East, it was noted: ‘Serious architects seek to develop a regional style: perhaps within the next decade they will have found the way.’16 There were dark suggestions in the journals that some architects ignored local sensibilities, but it was never the actual architects who were under discussion, always ‘someone else’. Whether it was a town plan or the design of a hospital or school, there was a consideration of how local tradition and culture could be accommodated in building types and plans unfamiliar in the region. This was particularly the case in the Gulf region. It was possible to take a very functional approach, which suited those buildings needed for strictly utilitarian purposes such as desalination plants. More difficult were buildings such as hospitals where functionalism needed to be tempered with some degree of cultural sensibility.

The desire for modern building and technology had provided a strong incentive since the 19th century for the regions of the Middle East to engage with the west. Their desire for modern technology did not always coincide with a preference for western culture or politics, which may have been a misconception laboured under by developed western nations. By the middle of the 20th century, the idea of ‘modernity’ carried a certain prestige, and countries coming into sudden wealth could be expected to seek some of that prestige for themselves.17 It should be remembered, however, that at the same time the Middle East was seeking to transform its physical fabric with modern buildings, America – and to a certain extent Europe – were also changing the face of their own cities. The Gulf States were not trying to keep up with an already well-established modernism, but with a contemporary process that was happening all around the world at that time. In other words, they were not playing catch-up, but regarded themselves also as the present or even the future. This was reflected in the title of a 1975 feature in the Architectural Record, which asked if the Middle East was indeed the ‘new frontier’.18

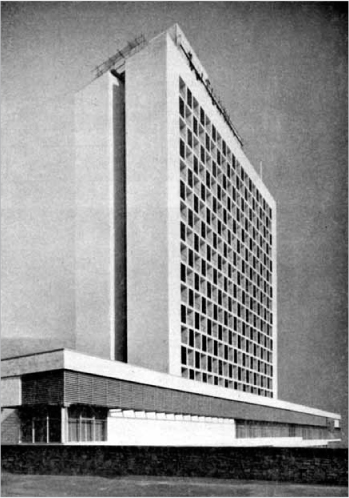

However, there was a lot of building needed in the Gulf States, and much of it involved infrastructure undertaken by large contractors such as the British firms Taylor Woodrow, Laing and Costain. Architectural work, on the other hand, was varied, and needed to satisfy the demands of a wide variety of clients. For example, Raglan Squire and Partners became involved with Hilton Hotels, which along with Intercontinental Hotels and Holiday Inn were building extensively in developing countries in the Middle East, Far East and Caribbean. Squire claimed that every Hilton Hotel was different, and his personal experience of these hotels ranged from Tehran and Bahrain to Cyprus and Tunis and to Jakarta.19 But as Annabel Wharton has pointed out in her book, Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture, there was also a formula which incorporated the accepted luxury of contemporary America with just a modicum of regional decoration.20 The Hiltons provided a comfortable familiarity for wealthy western visitors, but they also satisfied the desire for a palpable modernity from the ruling elites in the cities where they were built, sometimes in the face of great difficulty and expense. Wharton makes the telling point that Conrad Hilton actually did not pay for his new hotels, but relied on local investment, thus ensuring the support of the financial community at any rate for the shiny new buildings – which with their monumental scale often dramatically changed the urban landscape, and served to emphasise the ‘shabbiness’ of the traditional fabric.21

2.4 Tehran Hilton Hotel by Raglan Squire Architects

2.5 Bahrain Hilton Hotel by Raglan Squire Architects

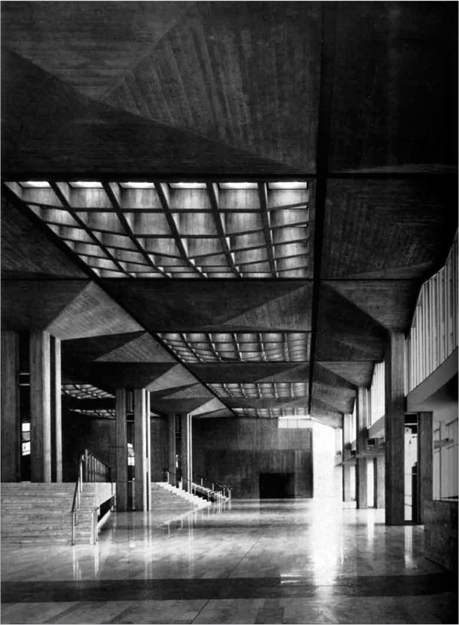

There were also buildings commissioned by Middle Eastern governments which could produce interesting work beyond the accepted modernist formula. In 1966 Trevor Dannatt won a limited international competition organized by the International Union of Architects on behalf of the Saudi government for a conference centre and hotel in Riyadh. This large project was completed in the mid-1970s, but the generosity of the spaces and the simple forms give the complex a timeless quality.22 Anglo-American architects are often uncomfortable with religion, or at least they have been in the recent past; hence many of them found the omnipresence of Islam and the other religions of the region a struggle. Nonetheless, Sherban Cantacuzino attributed the success of the Riyadh Conference Centre to ‘Trevor Dannatt’s nonconformist background and his understanding of Wahabi puritanism’.23 Be this as it may, it is noticeable that from Dannatt’s design are absent those pointed arches, decorative tiles and grills which seemed to be the limit of regional references for many new buildings in the Gulf at this time.

2.6 Conference Centre and Hotel in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, by Trevor Dannatt and Partners

2.7 Conference Centre and Hotel in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, by Trevor Dannatt and Partners

While building work in the Middle East continued to grow during the 1950s and 1960s, it was after the ‘oil crisis’ of 1973–1974 that the region’s impact on architectural practice reached a global scale. In 1976 Edmund Dell, the British Secretary of State for Trade, compared the expansion of the Arab countries as ‘the nearest modern industrial equivalent to the booming days of the American gold-rush’.24 We have become used over the past years to take in our stride references to billions of dollars, but in 1975 the Central Planning Organization of Saudi Arabia was already forecasting that their government would be spending $27 billion a year on construction by 1980.25 The resulting interest was enormous, since the very crisis which brought such wealth to the oil-producing countries was also pushing the industrial countries into recession. Dispiriting statistics continued to appear in the architectural press in the mid-to-late 1970s chronicling the fall in new commissions for British architects at home.26

It thus became more common for the architectural journals to cover work in the Middle East, and even to devote whole issues to working in the region. In January 1976 a brand new journal, Middle East Construction, was launched with a quotation from Le Corbusier on its cover and a remit to circulate itself free-of-charge to ‘qualified readers’ in the whole Gulf region. From the early issues of the journal it became clear that construction was viewed as a vital element in the British government’s export drive, especially as it was considered that Britain was falling behind other countries such as America, Japan and Germany.27 The stiff competition between industrialized countries for work in the oil-rich areas of the Middle East signals the change in the balance of power between those commissioning the work and the providers of design and construction services.

Although Britain was historically the major colonial power in the Gulf region, America had by the 1970s built up a long history of involvement in the area, especially since their interest in oil pre-dated the Second World War. Saudi Arabia’s first oil concession in 1933 went to what became the Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO), and when oil was discovered in Dhahran in 1938, it was that company which took control of the refining, marketing and pricing of the oil. They also developed the area with their own infrastructure, and established in effect an American company town for its workers. Indeed, the US government fostered Saudi Arabia as their particular ally in the area, and one of their ministers even likened the Kingdom in the 1940s to ‘a gigantic aircraft carrier, astride the Middle East’.28 Subsequently, American architects and engineers began to undertake a significant amount of work in the Middle East, a fact reflected in the June 1975 issue of Architectural Record, which was devoted to opportunities for US designers in the area and chronicled the experience of architects already working there. The Americans were also much more upfront than the British about the cultural conflicts incipient in the relations between Gulf clients and western designers. They recognized the resentment felt at the ‘demeaning’ attitudes of many Americans, but they also noted that: ‘These leaders are also conscious of their image, and the superficial image that many want – for better or for worse – is that of America.’29 The efficiency of American methods was appreciated, especially since time was regarded as of supreme importance. There was very much a concern among leaders in the Gulf that building, along with diversification, should take place while the oil revenues lasted, so that the region would not ever sink back into obscurity when it could no longer provide oil to the industrialized economies.

The Architectural Record gave advice on how to get commissions, and mentioned the need for a reliable agent who would be able to set up face-to-face meetings with Middle Eastern clients. Sometimes western architects might have to wait around for weeks before their all-important meeting, and, as they were reminded, this was without benefit of alcohol or the usual kind of western entertainments such as movies.30 When it came to the contract, many westerners found that the timescale expected for the necessary design and building work was unexpectedly tight, and the expense of building was beyond what they were used to. Scarcity of materials and transport costs were a major consideration, and, as one architect asked half-jokingly, how do you mix concrete when the water temperature is 100°F?31

As mentioned before, even in the 1950s there was awareness that instant modernisation could wipe out any previous cultural traditions in the Gulf region. By the mid-1970s, and the oil boom that was happening, this situation seemed even more likely. Hans Neumann of Perkins & Will International described a sensitive plan for a new town near Tehran which had been rejected out of hand by the clients because it included traditional elements: ‘They didn’t want to hear the word bazaar. It was a shopping center.’32 On the other hand, Charles Hoyt criticised much of the recent work by westerners as being ‘poorly planned and built, and its designers have copied the appearance of (for example) Miami in the 1950s’, while Neumann remarked that the regions in the Middle East ‘need an immediate warning before they destroy their heritage’.33 This growing concern from the late-1970s coincides of course with the discovery of the importance of ‘built heritage’ in America and Britain, and could reflect western preoccupations just as much as international modernism had done twenty years before.

British architects too were increasingly aware of the cultural dimension of their activities in the Gulf region. Scott Brownrigg and Turner made a calculated decision in 1974 to get involved in Middle Eastern projects, and opened offices in Doha and Dubai. When they came to design the Abu Dhabi Trade Centre, as a spokesman explained, their architect had ‘completely misread the client’s requirements’, lazily assuming the client’s interest lay in prestige and hence their desire was for ostentation and wealth. The wry comment was that ‘SBT see a danger in being excessively conditioned by UK press and propaganda about Arab excess’.34

2.8 Advertisement for Syston Rolling Shutters

Some of the advertisements to be found in the architectural press at this time are as telling as the comments made by the architects involved. An advert from the RIBA Journal in 1977 for Syston Rolling Shutters presents a whole dramatic scenario which speaks volumes.35 An Arab millionaire, the former colonial subject, emerges from his limousine to be greeted by a smiling commissionaire, the uniformed representative of British colonialism, since hotel commissionaires then were largely staffed by former army personnel. ‘Times may be changing’ stated the text, and we must remember that this was when people from the Middle East were seen as ‘flooding’ London’s West End, eager to spend some of their oil wealth. The text went on to say that: ‘We care about maintaining standards, we never cut corners. We care about the personal touch, we’re never slow to respond to your needs and problems’. This suggests that there are others who will do all these things, especially if they are dealing with Middle East clients whom they think they can fleece.

In the July 1983 issue of the RIBA Journal, which was dedicated to ‘Architecture Overseas’, Hal Higgins of Higgins, Ney and Partners made the comment that: ‘The mistake that many western architects have made is to come into the Middle East with set western notions and to construct buildings which are unsuitable in a traditional sense. This attitude shows a certain contempt for the place in which they are building.’36 A second advertisement, appearing in the journal The Architect in December 1976, reflects something of this attitude.37 The advert is based on that old schoolboy joke, how do you make a Venetian blind? [Answer: You poke his eyes out!] The crudely drawn cartoon of a cigar-smoking Arab, with a set of blinds as eye shades, is posed in front of some oil derricks, and the text concluded with the phrase: ‘If you have to blind an Arab, try our service. It doesn’t hurt at all’. Much less subtle than the previous advert and perhaps so over-the-top as to become innocuous, it did after all appear in a special issue of The Architect devoted to the Middle East, with translations into Arabic.

If nothing else, these advertisements demonstrate the ambivalence of those in the British construction industry to working in the Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. Architectural firms such as Scott Brownrigg and Turner attributed their continuing existence during a period of severe recession to their work in the Gulf region. And for many British architects, it was an opportunity to work on a scale they could never dream of at home. On the other hand, Middle Eastern countries with new untold wealth sought to satisfy their desire for modernity without often really understanding the implications of this move. But when it came to thinking about architectural heritage, which countries in the west finally got around to doing in the late-1970s, it could be asked whose heritage: that of the ruling elite, or of the indigenous people? Or was it perhaps even the great mass of foreign workers drafted into a country such as Kuwait, where already by the mid-1980s some 60 per cent of the population was made up of outsiders, mostly Palestinians?38

In May 1977 the RIBA Journal assessed the past 25 years of British architects in developing countries such as those in the Gulf region, and the conclusion of Michael Austin-Smith was that architectural assistance was not enough, since undiluted western architecture could be inappropriate. As Austin-Smith said, ‘It is no good building a dozen hospitals or schools if there is no way of producing the necessary medical or teaching staff’.39 Then he went on to add:

There is therefore a great opportunity which is opening up for a whole range of British expertise to be applied to a large number of building programmes in a way which will ensure that our knowledge and expertise is used to solve the problems of the countries concerned and not to saddle them with inappropriate buildings.

And here we can see that the British were off again on another quest to run other peoples’ lives for them. Much of course has happened since in the Middle East in the way of regime change and revolution, shifts in balance of regional power, and the politics of oil. But when we regard the present condition of architecture within the Gulf States, it is good to remember that where we are now began in the post-war rush to modernity, and came from the self-interested involvement of western architects.

NOTES

1 Building, vol. 224, no. 6779 (1 July 1977): 42, 81; RIBA Journal, vol. 84, no. 5 (May 1977): 229.

2 W. Taylor Fain, American Ascendance and British Retreat in the Persian Gulf Region (New York: Palgrave & Macmillan, 2008), p. 15.

3 William L. Cleveland & Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East (4th Edition, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2009), p. 212.

4 Ibid., p. 190.

5 Ibid., p. 231.

6 Fain, American Ascendance, p. 22.

7 Raglan Squire, Portrait of an Architect (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1984), p. 147.

8 Ibid., p. 198.

9 Panayiota I. Pyla, ‘Baghdad’s Urban Regeneration, 1958: Aesthetics and the Politics of Nation Building’, in Sandy Isenstadt & Kishwar Rizvi, Modernism and the Middle East: Architecture and Politics in the Twentieth Century (Seattle, WA/London: University of Washington Press, 2008), p. 99.

10 Architectural Design, vol. 27, no. 3 (March 1957): 74.

11 Ibid.

12 Fain, American Ascendance, p. 3.

13 A.E.J. Morris, John R. Harris Architects (Westerham, Kent: Hurtwood Press, 1984), p. 5.

14 The Architect, vol. 122, no. 12 (December 1976): 30.

15 Morris, John R. Harris Architects, pp. 2–3.

16 Architectural Design, vol. 27, no. 3 (March 1957): 72.

17 RIBA Journal, vol. 84, no. 5 (May 1977): 198.

18 Architectural Record, vol. 157, no. 6 (June 1975): 101–108.

19 Squire, Portrait of an Architect, p. 205.

20 Annabel J. Wharton, Building the Cold War: Hilton International Hotels and Modern Architecture (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001), p. 4.

21 Ibid., p. 7.

22 Architectural Review, vol. 157, no. 938 (April 1975): 194–219.

23 Ibid., 216.

24 As quoted in The Architect, vol. 122, no. 12 (December 1976): 25.

25 Architectural Record, vol. 157, no. 6 (June 1975): 105.

26 See, for example, RIBA Journal, vol. 84, no. 10 (October 1977): 447.

27 Middle East Construction, vol. 1, no. 3 (March 1976): 5.

28 Fain, American Ascendance, p. 22.

29 Architectural Record, vol. 157, no. 6 (June 1975): 102.

30 Ibid., p. 103.

31 Ibid., p. 106.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid., p. 108.

34 The Architect, vol. 122, no. 12 (December 1976): 37.

35 RIBA Journal, vol. 84, no. 10 (October 1977): opposite p. 437.

36 RIBA Journal, vol. 90, no. 7 (July 1983): 4.

37 The Architect, vol. 122, no. 12 (December 1976): 62.

38 Cleveland & Bunton, Modern Middle East, p. 467.

39 RIBA Journal, vol. 84, no. 5 (May 1977), p. 198.