BUILDING PERFORMANCE EVALUATION IN THE UK

So many false dawns

Introduction

In the 1960s, the imperative to move architecture on to a more scientific footing led to an interest in evaluating the performance of buildings in use and feeding back the results. In the 1970s, this early promise became severely eroded. Since then, there have been several cycles during which interest and capabilities have grown and then faded away. Why has it been so difficult for the industry, its clients and government to adopt routine building performance evaluation (BPE) and feedback, and what can be done about it?

Some developments in the UK from 1960 to 2002

The history of post-occupancy evaluation (POE) in North America is outlined in Chapter 14. In the UK, POE also emerged in the 1960s, as part of a policy to move architecture on to a more scientific footing. A review of architectural practice for RIBA, the Royal Institute of British Architects (Derbyshire and Austin-Smith 1962) led on to its Plan of Work for design team operation (RIBA 1963). This included Stage M – Feedback, where architects would return to their projects after a year or so to review their performance in use.

In 1967, the Building Performance Research Unit (BPRU) was set up at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, to undertake feedback, bring together research, teaching, and design on building performance, and publish the results. In 1968, BPRU started a major project, sponsored by the Ministry of Public Building and Works, the RIBA, the Architects’ Journal, and 20 architectural and engineering practices. This focused on newly built comprehensive schools, for ages 11–18. The results were published in the book Building Performance (Markus et al. 1972). Today its findings still ring true, for example an obsession with first cost; repeated mistakes; poor strategic fits between buildings and the activities inside them; and single issues – particularly daylight factors – dominating the design and preventing effective integration, whilst often not being achieved themselves.

Building Performance should have been required reading for participants in the UK’s recent ‘Building Schools for the Future programme’, where eye-catching architectural design (and sometimes banal contractor design) has too often trumped functionality, with poor environmental performance (Partnerships for Schools 2011) and high capital and running costs. Yet again these have exposed the differences between the views of architectural critics, and what physical measurements and occupant surveys reveal. A former student at one award-winning school summed it up (Anon. 2012): ‘the architecture showed next to no sense. It leaked in the rain and was intolerably hot in sunlight. Pretty perhaps, sustainable maybe, but practical it is not.’ The comment was supported by POE results. In this chapter we use BPE to designate the general activity of building performance evaluation and POE for BPE undertaken in the first two or three years after a building’s occupation, where the findings can influence those who commissioned and undertook the design and building work.

Building Performance included a plea for architects to get more involved in BPE and feedback, and provided strong arguments why. Unfortunately, this did not happen – the first false dawn. In 1972, the very year it was published, RIBA took Stage M out of its Architects Appointment document, reportedly because clients were not willing to pay for feedback as an additional service; and RIBA did not want to create the impression that architects would do it for nothing. While Stage M remained in the Plan of Work, architects did very little routine feedback subsequently, as has been reviewed by Duffy in this volume. Fortunately, the latest version of the Plan of Work (RIBA 2013) does include more about activities beyond physical completion, in Stage 6 (“Handover and Closeout”) and a new Stage 7 (“In Use”). However the contents of these stages are not yet well defined, particularly Stage 7.

The publication of Building Performance also marked the end of BPRU’s government/industry/academe/publisher collaboration, not the first step on a journey to BPE as a discipline, connecting research, practice and clients. A statement in the book may reveal why: ‘BPRU was more interested in research than in developing devices, however practical, without a sound theoretical framework.’ Developing theory at the expense of practical opportunities for improvement may fit the priorities of academe, but may well have distanced BPRU from the designers, clients, operators and users it had originally aimed to serve. Time and again we find a mismatch between the priorities and practices of academe, the criteria for research funding, and the interests of building professionals and their clients. It has been particularly difficult to obtain funding for multi-disciplinary research into the combined effects of people, processes, techniques and technologies; and for broad-based case studies that concentrate on outcomes.

For the remainder of the 1970s, Britain’s economic difficulties, exacerbated by energy crises in 1973 and 1979, suppressed the amount of new building and the appetite of clients and government for BPE, in spite of the constant lessons that better feedback from building performance in use promised to make future buildings both cheaper and better. However, one aspect of building performance – energy use – began to receive considerable attention, leading to developments in regulation (mostly for insulation), energy management (including benchmarking and subsidized energy surveys), and new techniques and technologies (with grants for demonstration projects). In 1974 the UK set up the Department of Energy (DEn) to deal with both the supply side (in particular North Sea oil) and to some extent the demand side. In 1977, demand management obtained a similar status. The UK’s energy efficiency policies from 1973 to 2013 are reviewed by Mallaburn and Eyre (2013).

In 1974 DEn set up the Energy Technology Support Unit (ETSU) at the Harwell national laboratory to provide technical and research support. In 1976, the Department of Industry added a programme for industry, coordinated by the National Physical Laboratory. In 1978, the Department of the Environment (DoE) established a companion unit (BRECSU) in its Building Research Establishment (BRE). In 1983, DEn set up the EEO, the Energy Efficiency Office, to help coordinate these three streams of demand-side work and present the results.

The 1980s

In the early 1980s, interesting low-energy buildings had been constructed and useful feedback was being obtained. Another false dawn. Later in the decade, progress slackened, owing to falling fuel prices, a political belief in the efficiency of the marketplace, plans to privatize the gas and electricity industries, and a shift in emphasis from conservation to efficiency. As a result, many opportunities for improving building performance remained unrecognized or undeveloped. A generic problem also emerged: a preference to celebrate and often over-play successes (or supposed successes), but not to publish the findings from failures, so allowing mistakes to be repeated indefinitely.

In the late 1980s, DEn’s prime focus was to privatize the gas and electricity industries and then to extinguish itself. In the process, EEO, the Energy Efficiency Office, was scaled down, its energy demonstration and survey schemes replaced by the Energy Efficiency Best Practice programme, EEBBp. This had four interrelated elements: Energy Consumption Guides, with benchmarks and action items; Good Practice guides and case studies to help stimulate adoption of energy-saving techniques and technologies; New Practice guides, case studies, events and visits; and Future Practice. R&D under the New and Future banners was more about liaising and disseminating results than funding research itself.

In 1992, DEn was abolished and the EEO moved to DoE, the Department of the Environment, which was responsible for many aspects of buildings including regulation, the government estate, construction industry sponsorship and BRE. In spite of this convergence, BRECSU’s support to the EEO programme was only weakly connected to BRE’s work as a national laboratory.

In the 1980s, there was also some private sector interest in BPE, in particular to support the energy-related work, the growth of facilities management, and in a few design practices. For example, in 1979, four architectural firms got together to help create Building Use Studies Ltd (BUS), largely to work on briefing/programming, human factors and occupant surveys. In the event, the vast majority of BUS’s commissions were not from architects but for research projects, construction clients and building managers. One major commission, the Office Environment Survey (Wilson and Hedge 1986), analysed responses to a 20-page questionnaire on occupant health, comfort and productivity from a total of 5,000 respondents in 50 office buildings. This provided a foundation for further work in the 1990s and beyond, including Raw (1992) and the Probe studies (Building Research & Information 2001).

Following the Bruntland Report (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987), climate change came to the fore in UK government policy. Key milestones were Margaret Thatcher’s speeches to the Royal Society in 1988 and to the United Nations on the global environment in November 1989. From then on, the UK took a leading role in climate issues internationally, though the rhetoric tended to run well ahead of the action. Under the UK’s present government (2010–15), both the leadership and the action are collapsing.

The 1990s

Recognition of climate change at the highest policy level, together with other developments including the launch of BREEAM, the BRE Environmental Assessment Method (Baldwin et al. 1990), boded well for improving the performance of buildings in use. Good progress was made in the early 1990s, with energy joining other work on building and environmental performance at DoE and BRE, supplemented by a new Energy-Related Environmental Issues programme EnREI. More projects evaluated building performance from multiple perspectives – human, technical and environmental, for example Bordass et al. (1994).

In 1995, DoE started a new programme – Partners in Technology (PiT) – into which anyone could bid. PiT (later called Partners in Innovation, PiI), supported some multi-disciplinary work on building performance, including Probe – Post-occupancy review of buildings and their engineering – which undertook and published 20 POEs of recently completed buildings between 1995 and 2002. The work was initiated by the editorial board of Building Services – the CIBSE Journal. The EEBBp then funded a review of the first 16 Probe studies, the Probe process and the strategic and tactical lessons: these were summarized in a special issue of Building Research & Information (2001). The review identified major problems with the way that buildings were procured, and considered the implications for briefing/programming, design, construction, commissioning, handover and management; and for government policy. Although all but one of the Probe buildings were in the UK, the findings also resonated in other countries, particularly in North America, Australia and Europe. The Dutch even republished the five papers from the special issue. Perhaps the most important findings were the need for better procurement processes that focused on outcomes; and that unmanageable complication was the enemy of good performance.

Sadly, over the same period, the UK government’s own insights into building performance had been leaking away, as it outsourced its design and property management skills and privatized its national laboratories: not just BRE, but also Harwell (where ETSU was based); and the electricity and gas industry laboratories which had also monitored performance of people, buildings and plant. DoE was also dismembered, its building-related activities dispersed to various ministries and agencies, with no common core.

As a result, government increasingly turned to the construction industry for advice on building performance – something the industry knew little about, as it didn’t routinely follow through into use and capture the feedback (Blyth and Edie 2000). As Duffy (2008), a former president of the RIBA, wrote:

unlike medicine, the professions in construction have not developed a tradition of practice-based user research … Plentiful data about design performance are out there, in the field … Our shame is that we don’t make anything like enough use of it.

Two government-sponsored reports consolidated the confusion of building performance with construction: Rethinking Construction (Egan 1998) and Rethinking Construction Innovation and Research (Fairclough 2002). Amongst other things, the Egan Report advocated customer focus, ambitious targets and effective measurement of performance. However, when it came to its implementation, the focus was almost entirely on construction time, cost and elimination of defects; not understanding fitness for purpose. Government took the view that the industry should get things ‘right first time’, not seeing the need for follow-through from construction into operation. However, lacking good routine feedback information, neither government nor industry knew what ‘right’ really meant.

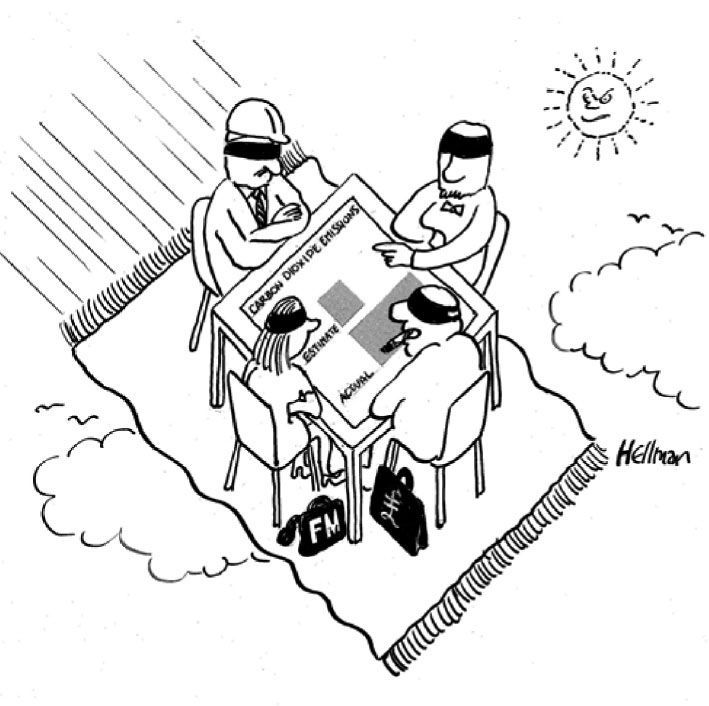

In 2001, the Association for the Conservation of Energy published two reports that pointed out the enormous gaps that had opened up between design intent and reality in energy performance: Building in Ignorance (Olivier 2001) for housing and Flying Blind (Bordass 2001) for commercial buildings. Figure 15.1 shows the cover illustration, with the designer, builder, facilities manager and owner of a recently completed building all ignoring the evidence of a big difference between estimated and actual performance, what is now known as the Performance Gap. (The data for the graph shown on the table in Figure 15.1 came from a building that had won a sustainability award.) Flying Blind advocated using energy certificates to disclose actual performance and to motivate action. It also expressed its concern about the dangers of fragmentation of the buildings and energy policy that had previously been concentrated in DoE.

FIGURE 15.1 The cover illustration from Flying Blind (Bordass 2001)

Source: Louis Hellman.

The past decade

Fairclough (2002) considered the implications for government research of the completion of the five-year transitional arrangements following the privatization of BRE in 1997. The report saw the construction industry as largely responsible for innovation and research; but did identify four areas in which government might need to fund building research directly: as regulator, sponsor, and client, and ‘for issues that go wider than the construction industry’, mentioning climate change, energy and unforeseen circumstances. However, it regarded in-use performance as more a matter for regulation. One unfortunate result was that Partners in Innovation, the government programme that had helped to fund Probe and other industry-relevant research on building performance in use, was transferred to the Department of Trade and Industry and was soon closed down.

From 2000 to 2010, the UK had a major public buildings programme, especially for health and educational buildings. However, the focus was on construction and on design in the architectural sense, not on outcomes. It also used a tick-box approach to sustainability, which tends to favour additive, over-complicated buildings to simple, thoughtfully integrated ones. The favoured method of procurement was PFI, the Private Finance Initiative, where a contractor finances, designs, builds and operates. PFI’s main purpose was to keep the capital cost of public assets off the balance sheet. Policy-makers also thought that the single point responsibility would increase emphasis on performance in use, though we feared this might not happen (Bordass et al. 2002).

Since about 2008, a number of developments reveal a growing interest in in-use performance, including the formation of a new ministry, DECC, the Department of Energy and Climate Change, which has begun to put more emphasis on demand and not just supply. Unfortunately DECC has little access to institutional memory owing to the outsourcing culture, the privatization of the UK’s national laboratories, and the loss of key staff. Starting in 2010, the Technology Strategy Board (which is supported by BIS, the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills) has also funded about 100 BPE studies of recently completed buildings (about half domestic and half non-domestic), together with other projects on low-energy retrofit, design and decision-making, construction process and energy management. Universities and design practices are also showing more interest in BPE and POE. However, policy-makers continue to regard building performance in use as largely a matter for the construction industry, for example in establishing the Green Construction Board; and always seem to be asking for more statistics, not more case studies.

The Usable Buildings Trust

With government connection to building performance in use diminishing, departmental responsibilities fragmenting, and the design professions not filling the gap that was opening up, in 2002 the authors helped to set up the Usable Buildings Trust (UBT), a not-for-profit charity. UBT helps to connect people, collect and disseminate information, and embed the concept of in-use performance into policy and practice. Over the past ten years, we have had some modest successes but considerable setbacks. Three examples are outlined below.

Clients. Since few designers and builders had the appetite to make POE routine, we obtained funding for a project on feedback for construction clients, who we hoped would take the lead, in their own interests. We then got a shock, as the study revealed that the concerns of major clients were mostly about project management, delivery and defects: inputs and outputs, not outcomes apart from capital cost. This is perhaps not surprising for the speculative buildings that predominate in the UK, but similar attitudes were often found in procurement departments of many clients that retained their building stock, e.g. universities and housing associations. Those most interested in performance in operation tended to be one-off clients procuring buildings for their own use. Among major clients, we also found some individuals committed to good outcomes, but their reflective nature tended not to fit the organizational culture, so after one success they would often move on to other jobs.

Energy certificates. UBT helped to develop strategy and detail for the energy certificates required under the European Union’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (OJEC 2003). We argued that the certificates required for display in ‘public buildings and buildings frequently visited by the public’ should be based on actual metred energy use and updated annually. UBT also assisted with strategy for these Display Energy Certificates (DECs), for example in Onto the Radar (UBT 2005). The hope was that DECs would make energy performance in use visible and actionable; extend in due course from public to commercial buildings and from larger into smaller buildings; and also encourage people to measure other aspects of in-use performance, e.g. occupant satisfaction and productivity. DECs were introduced in England and Wales in 2008 for public buildings only. They have had some effect, but sadly the government has not given proper support to further development and benchmarking, which has hindered their extension to commercial buildings. As the government lacks a focal point for policy-making for buildings and energy, or a consistent technical infrastructure, it has also introduced other systems of reporting that are conflicting, not complementary.

Soft Landings. The Probe team identified deficiencies in how building work was procured. Too often there was inadequate briefing/programming and little or no continuity from client and design intent to completion and handover, and on into operation. UBT therefore helped to research and develop the Soft Landings process (Way and Bordass 2005), which was taken further with an industry group convened by BSRIA, the Building Services Research & Information Association. Outputs include a published Framework (Way et al. 2009), case studies including some of schools sponsored by the Technology Strategy Board, and other documents. Soft Landings can potentially be grafted onto any procurement system, for any building project, in any country. It aims to improve a project’s focus on outcomes, in particular augmenting five stages: (1) Briefing/programming; (2) Expectations management during design and construction; (3) Preparation for handover; (4) Initial aftercare, and (5) Longer-term aftercare and POE. It is designed to bring out the leaders, allowing client and team members to set priorities and assign tasks. The government has decided to adopt the principles for public sector procurement projects, but has decided to codify them more than we would have preferred. This creates a risk that government Soft Landings will turn into yet another ossified standard, with the process being regarded as a substitute for leadership, but only time will tell.

Who owns building performance? Avoiding another false dawn

Buildings last a long time, well beyond the time horizons of their creators. Good performance in use is in the public interest, but is the result of the actions of many players. Sadly, and in spite of all the evidence, it has been difficult for policy-makers to appreciate that building performance is about a lot more than construction, and to get joined-up government thinking and action. We see performance in use as too important to be entrusted to designers and builders alone; and certainly not just to architects, who are no longer ‘leaders of the team’, as they were in the UK 50 years ago.

In his commentary on Probe, Cooper (2001) raised a fundamental question: which party involved in the procurement and operation of buildings owns POE? At the time, the authors (Bordass et al. 2002) thought that follow-through and feedback would become routine practice as something clients would want and pay for, in terms of the benefits and savings it would bring. However, this was before we discovered that major clients were less interested in building performance in use than we had expected. Ten years later, the British government’s intention to mandate Soft Landings for public procurement from 2016 suggests that the tide is turning.

How best can this increasing interest in performance in use be supported? UBT considers that it will need cultural changes and new institutions.

A new professionalism

In terms of cultural changes, UBT has been advocating a new professionalism, where all building professionals engage much more closely with the consequences of their actions. This is already implicit in the codes of many professional institutions, which require members to understand and practise sustainable development. The Institution of Civil Engineers even expects its members to ‘do the right thing’. At present, these aspirations are too often honoured in the breach.

UBT helped to arrange a debate in London in 2011 on the role of the building professional in the twenty-first century, by the Edge, a multi-disciplinary group that considers emerging issues in the built environment (see http://www.edgedebate.com). Speakers identified many gaps: between professions; between practice and academe; and between design assumptions and how buildings work in use, owing to a failure to develop a shared knowledge base. Solutions were seen to lie in ethics, integration, practice based on evidence, and an action-learning culture. Some thought the UK had the necessary knowledge and skills, but lacked the resolve to bring them together.

Building Research & Information then issued a call for papers on New Professionalism, leading to a special issue on the subject (Building Research & Information 2013). This was discussed at another Edge debate, where the authors of four of the papers presented their views, after which questions from the audience were debated by a panel of senior representatives of UK professional institutions in architecture, engineering, surveying and construction.

It was agreed that the challenges of sustainability were exposing inadequacies of regulations and markets, and creating a vacuum that building professionals and their institutions could help to fill. However, the meeting was not sure whether they would have the will to do so, the necessary capabilities, or whether society would trust them in this role. Critical needs were identified for:

• a shared vision and identity for practice and education, with more emphasis on ethical aspects and perhaps something similar to the Hippocratic Oath;

• better procurement processes, with a proper focus on outcomes;

• building performance in use to become a properly recognized and represented knowledge domain.

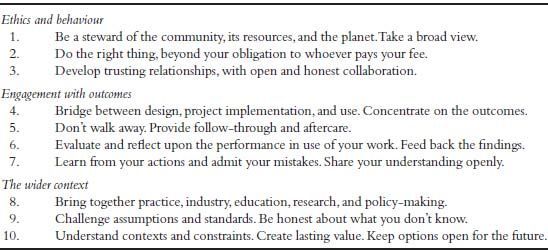

After the first debate, the Edge suggested developing some shared principles that any built environment professional could adopt – today. The ten points that emerged are shown in Figure 15.2. They fall into three groups: (1) ethics and behaviour; (2) engagement with outcomes, reflecting and sharing knowledge; and (3) the wider context of policy, practice, education and research.

FIGURE 15.2 Elements of a new professionalism: ten points developed with the Edge

Source: adapted from Building Research & Information (2013: Table 1, p. 6).

Conclusion: Reinforcing the knowledge domain of building performance

How can society best support the development of a built environment in which much more emphasis is given to in-use performance outcomes, not just for new buildings but in the improvement of the existing stock? How do we avoid yet more false dawns? The change in attitudes and practices of a new professionalism need institutional and educational support. Our view is that the existing institutions will not be able to move fast enough. We need new structures that can both support and challenge them.

Fairclough (2002) identified the need for government to sponsor research that went wider than the construction industry. We put performance in use in this category. However, in the current political climate, it seems unlikely that it will obtain government funding to the extent necessary. Since the late 1970s, the prevailing worldview has been to leave things to the market. As a result, government no longer wants to build technical capacity itself, but looks to industry for solutions. But what industry owns building performance; and should any industry own it anyway? Not the construction industry: it regards buildings largely as construction projects. Not the property industry, which sees them as money machines. In the 1980s, we had great hopes for the emerging facilities management profession, but have been disappointed by the way this industry has developed. The UK government also put its faith in PFI, the Private Finance Initiative, where a contractor finances, designs, builds and operates public assets. We expressed concern about this (Bordass et al. 2002); and in the event it has too often produced buildings that were expensive, inappropriate or of poor quality.

UBT has concluded that society needs new institutions to develop and properly represent the knowledge domain of building performance in use. They would have the following attributes:

• independent, public interest;

• interdisciplinary from the start. No historic silos;

• authoritative, evidence based. Able to bring together work from many different sources;

• connecting research, practice and policy-making;

• able both to support and challenge the construction and property industries.

The authors are seeking philanthropic support to get this started.

Acknowledgments

© Bill Bordass and Adrian Leaman 2013.

References

Anon. (2012) https://www.worldarchitecturenews.com/index.php?fuseaction=wanappln.projectview&upload_id=11781

Baldwin, R., S. Leach, J. Doggart, and M. Attenborough (1990) BREEAM 1/90: An Environmental Assessment for New Office Designs. Garston, UK: Building Research Establishment, Report No. BR 183.

Blyth, A, and A. Edie (2000) CRISP Consultancy Commission 00/02: How Can Long-Term Building Performance Be Built In? London: Construction Research & Innovation Strategy Panel.

Bordass, B. (2001) Flying Blind – Everything You Wanted to Know about Energy in Commercial Buildings But Were Afraid To Ask. London: Association for the Conservation of Energy. http://www.usablebuildings.co.uk

Bordass, B., A. Leaman, and R. Cohen (2002) ‘Walking the Tightrope: The Probe Team’s Response to BRI Comments’. Building Research & Information 30(1): 62–72.

Bordass, B., A. Leaman, and S. Willis (1994) ‘Control Strategies for Building Services: The Role of the User’. Garston, UK: BRE/CIB Conference on Buildings and the Environment, Methods Paper 4.

Building Research & Information (2001) Special Issue: Post-Occupancy Evaluation 29(2): 79–174. http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rbri20/29/2. The original papers in the Probe series in Building Services – the CIBSE Journal can also be downloaded from the Probe section of http://www.usablebuildings.co.uk

Building Research & Information (2013) Special Issue: New Professionalism 41(1): 1–128. http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rbri20/41/1

Cooper, I. (2001) ‘Post-Occupancy Evaluation: Where Are You?’ Building Research & Information 29(2): 158–63.

Derbyshire, A. and J. Austin-Smith (1962) The Architect and his Office: A Survey of Organization, Staffing, Quality of Service and Productivity. London: RIBA.

Duffy, F. (2008) ‘Linking Theory Back to Practice’. Building Research & Information 36(6): 655–8.

Egan, J. (1998) Rethinking Construction: The Report of the Construction Task Force. London: Department of Trade and Industry.

Fairclough, J. (2002) Rethinking Construction Innovation and Research. London: Department of Transport, Local Government and the Regions and the Department of Trade and Industry.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006) ‘Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research’. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2): 219–45.

Mallaburn, P. and N. Eyre (2013) ‘Lessons from Energy Efficiency Policy and Programmes in the UK from 1973 to 2013’. Energy Efficiency Journal 7(1): 23–41.

Markus, T., P. Whyman, J. Morgan, D. Whitton, T. Maver, D. Canter, and J. Fleming (1972) Building Performance. London: Applied Science Publishers.

OJEC – Official Journal of the European Communities (2003) Directive 2002/91/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of [h1] 15. December 2002 on the energy performance of buildings, L1.65–71, 4 January.

Olivier, D. (2001) Building in Ignorance. London: Association for the Conservation of Energy. http://www.usablebuildings.co.uk

Partnerships for Schools (2011) Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Schools 2010–11. http://www.building.co.uk/Journals/2012/04/26/o/q/p/POE-full_report.pdf

Raw, G. (1992) Sick Building Syndrome: A Review of the Evidence on Causes and Solutions. HSE Contract Research Report 42/1992. London: HMSO.

RIBA (1963) Plan of Work for Design Team Operation. London: Royal Institute of British Architects.

RIBA (2013) Plan of Work Overview. London: Royal Institute of British Architects. http://www.ribaplanofwork.com/Download.aspx

UBT (2005) Onto the Radar: How Energy Performance Certification and Benchmarking Might Work for Nondomestic Buildings in Operation, Using Actual Energy Consumption. Usable Buildings Trust. http://www.usablebuildings.co.uk

Way, M. and B. Bordass (2005) ‘Making Feedback and Post-Occupancy Evaluation Routine 2: Soft Landings’. Building Research & Information 33(4): 353–60.

Way, M., B. Bordass, A. Leaman, and R. Bunn (2009) The Soft Landings Framework. Bracknell, UK: BSRIA, BG 4/2009.

Wilson, S. and A. Hedge (1986) The Office Environment Survey: A Study of Building Sickness. London: Building Use Studies Ltd.

World Commission on Environment and Development (1987) Our Common Future. New York: United Nations.