BUILDING PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS AND UNIVERSAL DESIGN

Introduction

The discipline of architecture involves many things. Architecture is both art and science, the issues faced are both aesthetic and practical, and problem-solving is rooted in both convention and innovation. Likewise, architectural design involves both “inclusive” thinking and “discriminatory” thinking – the integration of ideas and things, as well as the editing out of ideas and things. Yet the term “discrimination” takes on at least two distinct meanings – (1) a general sense: discrimination as a process of recognizing differences or distinctions between ideas or things, and (2) a negative sense: e.g. racial discrimination, gender discrimination, etc. Naming, categorizing, and organizing are forms of discrimination and are common processes in architectural design. Architects use clearly named architectural concepts, elements, and components like enfilade, parapet, and balustrade to design buildings; they work within established programmatic categories, such as “residential,” “educational,” and “industrial”; and they organize spaces and plans, for example, along corridors, around courtyards, or into gridded clusters. Designers broadly refer to these forms of discrimination as “typological thinking,” a central mode of decision-making in architectural education and practice. On the other hand, practitioners and the public tend not to think of negative forms of discrimination as an integral part of architecture. Both clients and the profession frequently conceptualize architectural works – and architects – as benevolent, humanitarian, and public-minded. In fact, a primary role of architects, among other design professions in the United States and elsewhere, is ensuring the “health, safety, and welfare” (HSW) of people. However, examples such as the famed Pruitt-Igoe housing complex – a project built in the mid-1950s in St. Louis, Missouri, USA, described as “particularly unappealing” and as a “world of troubles,” and subsequently torn down in the 1970s – demonstrate that not all architectural works fulfill the HSW mission (Rainwater 1970).

Throughout history, architects, and society in general, have displayed a variety of predilections, value systems, and ideologies regarding what constitutes “good architecture.” Many of these inclinations have been aesthetic, e.g. neo-classicism, modernism, brutalism. Other interests have focused on environmental issues, as evidenced in the sustainability movement; technological issues, exemplified in the emergence of digital design and fabrication; or on ethical issues, as seen in concepts like critical regionalism. These examples, nevertheless, are forms of discrimination; each one is a willful focus within what is a broad, complex, and changing discipline. This is not to say that any of these areas of specialization or interest is malevolent. On the contrary, areas of concentration often emerge out of practical necessity or in response to a perceived shortcoming in the discipline. The large point is that, whatever an architect chooses to emphasize in her or his practice – whether it be philosophical, aesthetic, or pragmatic in nature – buildings are never neutral and have physical, psychological, and social consequences for the humans that use them. Positively or negatively, design affects everyone.

FIGURE 23.1 Illustration of discriminatory design practice: sign at the main entrance to “Living Tomorrow: House and Office of the Future,” Amsterdam, Netherlands (architects: UNStudio, 2000–2003)

Source: photo by Korydon Smith.

While the now widespread sustainability movement has increased awareness about environmental issues in design, the universal design (UD) movement has advanced awareness about human diversity in design. Societies around the world have grown more diverse in terms of ethnicity, age range, health status, and other factors, necessitating broader and deeper knowledge of how these factors affect (and are affected by) architectural design. How can city parks be designed to be safe and enjoyable for both children and their grandparents? How can signs in airports be designed for English speakers, non-English speakers, and for persons with impaired vision? How can entrances be designed to accommodate wheelchairs, strollers, and foot-traffic?

During the latter half of the twentieth century, disability advocates and researchers, and some architects, realized that conventional design approaches resulted (mostly unintentionally) in segregated, stigmatizing solutions, especially for persons with physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities. The goal that emerged from UD (aka “inclusive design” and “design-for-all”), on the other hand, was to create integrated design solutions for a broader spectrum of the population. For example, rather than designing one building entrance for ambulatory users and a second entrance for visitors using wheelchairs and strollers (Figure 23.1), UD seeks to create one solution usable by everyone (Figure 23.2). This chapter discusses the philosophical and scientific underpinnings of UD, as well as the legal and aesthetic implications on the design and assessment of buildings.

FIGURE 23.2 Illustration of universal design practice: integrated stair, elevator, and signage in the main lobby of the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark (architects: C. F. Møller, 1998)

Source: photo by Korydon Smith.

The philosophy and science of universal design

The phrase “universal design” is commonly attributed to American architect Ron Mace (1985), yet the concept can be traced at least as far back as Bednar (1977). Since then, UD has become much more particular, namely with the articulation of ideas like the “Eight Goals of Universal Design” (Steinfeld and Maisel 2012). It is more important in the context of this book, however, to take a broader perspective. This begins through understanding that UD possesses both philosophical and empirical underpinnings. The empirical flank of UD stems from a set of interdisciplinary sciences that emerged in the mid-twentieth century, including: ergonomics and anthropometry, environmental psychology and behavior, and post-occupancy evaluation. Ergonomics, often used interchangeably with “human factors,” is the study of humans’ interface with the built environment and how building and product design makes tasks easier or more challenging; particular emphasis is placed on productivity, efficiency, health, and safety in work settings (Salvendy 2012). Anthropometry, the measurement of human bodies and movements, is particularly important to ergonomics. The design of spaces (organization and layout), workstations (chairs, desks, etc.), and machines, tools, and instruments, affects comfort, stamina, accuracy, speed, and other aspects of human functioning. In addition, graphic design, lighting design, acoustic design, and design for other senses affect human performance and, thus, are central to the science of ergonomics.

With much overlap to ergonomics, environmental psychology research explores how built and natural environments affect human emotion, cognition, and behavior. The field of environmental psychology flourished during the mid-twentieth century with the works of Altman and Chemers (1980), Gibson (1977), Kaplan and Kaplan (1978), Rapoport (1977), and Sommer (1969). Acceptance among architects waned in the last part of the twentieth century, but, with clients’ increased emphasis on empirically measurable outcomes and on “evidence-based design” (EBD), environment–behavior research is again on the rise (Bechtel and Churchman 2002). Post-occupancy evaluation (POE), a comprehensive field that assesses building performance – including operating costs, environmental efficiency, maintenance requirements, human performance, user satisfaction, and other measures – is a clear form of EBD. The number of books published on POE (e.g. Anderzhon et al. 2007; Federal Facilities Council 2001; Gupta and Stevenson 2012; Preiser et al. 1988) points to the continued value in and need for architectural research of this kind. Scientifically reliable methodologies have provided further legitimacy to the UD movement.

The philosophical flank of UD rests upon principles of social justice and a theoretical paradigm generally termed “critical theory.” Critical theory is a concept utilized in literary criticism, philosophy, and the social sciences, with differing meanings in each. The philosophical and sociological meanings possess the most relevance to UD concepts. The purpose of critical theory is “to liberate human beings from the circumstances that enslave them” (Horkheimer 1982). The goal of emancipation is achieved, first, by exposing the ways that hidden or explicit beliefs, values, laws, or systems negatively affect civil-, social-, and human rights, and then using education, advocacy, and/or public policy to foster change (Calhoun 1995). Inequality based on race, sex, economics, or religion, among others, is often the focus of a critical theorist, while providing equal access to decision-making power, property and capital, employment, and education is a common objective.

From a broader perspective, critical theory builds upon principles of social justice (e.g. Carver 1915; Miller 1999; Rawls 1999). More narrowly, critical theory takes many forms, such as “feminism,” an effort to draw attention to gender-based prejudices and create equal rights for women. Both social justice, generally, and feminism, in particular, have traditionally focused on health care, voting rights, wages, and similar issues. More recently, however, architectural design has entered critical theory discourses, exemplified in Weismann’s (1992) feminist critique of architecture, as well as in recent books such as Design Like You Give a Damn (Architecture for Humanity 2006), Design for the Other 90% (Smith 2007), and Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism (Bell and Wakeford 2008). UD, more particularly, initially sought to expose and undo design discrimination regarding persons with physical, sensory, and cognitive disabilities, but has expanded to issues of gender, age, ethnicity, and other areas as well. The argument, in short, is that most buildings are designed for an idealized population –“healthy,” “able-bodied,” and “normal” – not for the reality of a population with diverse needs, abilities, and preferences. The populations of many countries have grown older, many countries are experiencing large numbers of severely injured war veterans, and improved medical science has led to increased diagnoses of various physical and psychological conditions and increased survival rates and life spans of people with severe disabilities: all of which has bolstered the UD movement.

Legal and aesthetic “codes”

Universal design has benefited from the confluence of more potent scientific research, an increased value in social justice, and striking demographic trends. One result is the proliferation of books published on UD and inclusive design since 2000 (e.g. Clarkson et al. 2003; Goldsmith 2000; Herwig 2008; Imrie and Hall 2001; Nussbaumer 2011; Preiser and Ostroff 2001; Preiser and Smith 2010; Pullin 2009; Sanford 2012; Smith et al. 2010; Steinfeld and Maisel 2012; Steinfeld and White 2010; Vavik 2009). A second outcome is the growing number of product designers, interior designers, architects, landscape architects, and urban designers and planners whose practices focus on UD concepts. A third, and potentially the most significant, product is the large number of national laws and local buildings codes throughout Asia, Europe, North America, and South America that now incorporate or reference UD (Preiser and Smith 2010). The United States’ Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) is a clear demonstration of a national law with sweeping impact on disability rights, building codes, and the built environment.

In the context of architecture, “codes” often refer to explicit legal requirements of the architect(s) and builder(s), e.g. fire codes, electrical codes, structural codes, plumbing codes. But “codes” also refer to implicit social norms or tacit collective agreements. Each culture possesses certain accepted or taboo behaviors. This holds true for academic and disciplinary sub-cultures as well. The discipline of painting, for instance, has adopted a variety of codes throughout history about what is and what is not considered acceptable subject matter or technique. Architecture is similar in this regard. Aesthetic codes – including stylistic trends, material fads, and technological innovations – sway and are swayed by both the values of architects and the opinions of the public about what is “good” architecture. UD is frequently discussed from an ergonomic or social justice perspective, and is mistakenly viewed – by proponents and skeptics alike – as an architectural movement without aesthetic discourse. For two primary reasons, however, the contention can be made that UD, at its core, is as much an aesthetic concept as it is a functionalist concept.

First, the difference between specialized design for disability, e.g. assistive technology, and the UD paradigm is important. While both design for disability and UD stem from social justice and civil rights, there are significant distinctions in their outcomes. Assistive technologies and other specialized features address very particular sensory, mobility, or cognitive needs, and, therefore, tend toward a specialized aesthetic, characterized by a medical, machine-like, or industrial appearance and feel. In an architectural setting, these features – such as wheelchair lifts, “handicapped” parking, grab bars, or Braille – appear objectified rather than integrated into a building’s spatial and material composition. UD, on the other hand, seeks a more integrated, seamless quality akin to Wright’s (1955) notion of structural, spatial, material, and formal “continuity,” where different elements of a building merge or blend into one another. In UD this is achieved through the forethought of how to integrate specialized features as well as by eliminating the need for most specialized equipment by considering solutions that meet the needs of a broader population. UD emerged from the desire to integrate, rather than segregate and stigmatize, design for disability and to improve design quality.

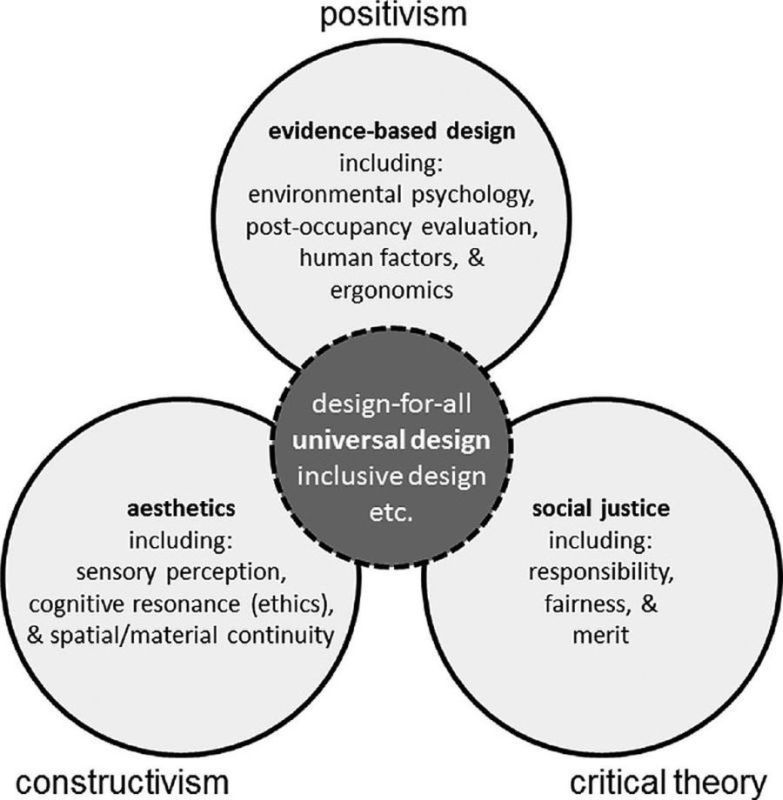

FIGURE 23.3 Conceptual diagram of the complementary paradigms of universal design

Source: Korydon Smith.

Second, aesthetics is an all-encompassing subject matter. Colloquially, aesthetics usually refers to the visual characteristics of a design. In philosophy, however, aesthetics refers to the emotional responses – feelings – one experiences from the visual, auditory, tactile, and other sensory stimuli of human art forms. Even more broadly, aesthetics includes an “observer’s” (listener’s, reader’s, etc.) cognitive sentiments about a particular art piece (painting, musical, story, etc.), including the relationship between ethics and aesthetics (Feldman 1970). This is where the ethical system of an observer is weighed against his or her perceptions of the moral codes an art piece conveys. In pondering an artwork, the observer may have feelings of frustration, pleasure, grief, ambiguity, emancipation, etc. Artist Josef Albers famously and succinctly stated, “I consider ethics and aesthetics as one.” The media of architecture are space and material. These two things – space and material – affect the ways in which people move, see, hear, and interact (aesthetics); and they affect, if tacitly, occupants’ conceptions of right and wrong (ethics). Designers utilizing a UD paradigm strive for ethical-aesthetic sensibilities of justness and satisfaction, or at least seek to reduce the likelihood of occupants feeling a sense of isolation, segregation, or discrimination. Ergonomics and usability play a role; building performance and efficiency play a role; continuity and integration play a role.

Conclusion

It is not a single paradigmatic shift that marks universal design thinking but a confluence of knowledge domains, including: environmental psychology, human factors, and POE; social justice; and aesthetics (Figure 23.3). These domains are frequently viewed as conflicting, yet universal design brings them together in a complementary manner, much like the complementary pairs described in Chapter 1. This results in a powerful, comprehensive means of assessing the value and significance of architectural works.

In this regard, UD parallels phenomenology, a philosophical approach and social science technique that sought to bridge the gap between positivism (objective, scientific inquiry) and constructivism (subjective, sociological inquiry). As architecture is a discipline that frequently draws from both objective fields, e.g. engineering, and subjective fields, e.g. fine art, it is clear why many architects, educators, and architectural theorists have adopted a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology, as a result, has had a tremendous impact on architectural education, criticism, and design. In the discipline and practice of architecture, phenomenology helps to synthesize what are often seen as binaries: pragmatics vs. poetics, context-specific design vs. universality, and objective phenomena vs. cultural phenomena. Universal design, in parallel, reveals the reciprocal relationship between aesthetics and social justice in architecture. Through this paradigm, aesthetics is necessary for assessing whether or not social justice has been achieved. Reciprocally, issues of social justice are integral to aesthetic “discrimination.” Aesthetics and social justice are not independent; they are interdependent, illuminated by the prospects and aspirations of the complementary paradigms of universal design.

References

Altman, I. and M. Chemers (1980) Culture and Environment. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Anderzhon, J. W., I. L. Fraley, and M. Green (2007) Design for Aging: Post-Occupancy Evaluations. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Architecture for Humanity (2006) Design Like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises. New York: Metropolis Books.

Bechtel, R. and A. Churchman (eds) (2002) Handbook of Environmental Psychology. New York: John Wiley.

Bednar, M. (1977) Barrier Free Environments. Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson, and Ross.

Bell, B. and K. Wakeford (2008) Expanding Architecture: Design as Activism. New York: Metropolis Books.

Calhoun, C. (1995) Critical Social Theory: Culture, History, and the Challenge of Difference. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carver, T. N. (1915) Essays in Social Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clarkson, J., R. Coleman, S. Keates, and C. Lebbon (eds) (2003) Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population. London: Springer-Verlag.

Federal Facilities Council (2001) Learning from our Buildings: A State-of-the-Practice Summary of Post-Occupancy Evaluation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Feldman, E. B. (1970) Becoming Human through Art: Aesthetic Experience in the School. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gibson, J. J. (1977) “The Theory of Affordances.” In R. Shaw and J. Bransford (eds), Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 67–82.

Goldsmith, S. (2000) Universal Design: A Manual of Practical Guidance for Architects. Oxford: Architectural Press.

Gupta, R. and F. Stevenson (2012) Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Buildings: Policy and Practice. London: Earthscan.

Herwig, O. (2008) Universal Design: Solutions for Barrier-Free Living, trans. L. Bruce. Basel: Birkhäuser-Verlag.

Horkheimer, M. (1982) Critical Theory. New York: Seabury Press.

Imrie, R. and P. Hall (2001) Inclusive Design: Designing and Developing Accessible Environments. London: Spon.

Kaplan, R. and S. Kaplan (1978) Humanscape: Environments for People. North Scituate, MA: Duxbury Press.

Miller, D. (1999) Principles of Social Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nussbaumer, L. (2011) Inclusive Design: A Universal Need. New York: Fairchild.

Preiser, W. F. E. and E. Ostroff (eds) (2001) Universal Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Preiser, W. F. E., H. Z. Rabinowitz, and E. T. White (1988) Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Preiser, W. F. E. and K. Smith (eds) (2010). Universal Design Handbook, 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pullin, G. (2009) Design Meets Disability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rainwater, L. (1970) Behind Ghetto Walls: Black Families in a Federal Slum. Chicago: Aldine.

Rapoport, A. (1977) The Mutual Interaction of People and their Built Environment: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. The Hague: Mouton.

Rawls, J. (1999) A Theory of Justice, rev. edn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Salvendy, G. (ed.) (2012) Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 4th edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Sanford, J. (2012) Universal Design as a Rehabilitation Strategy: Design for the Ages. New York: Springer.

Smith, C. (2007) Design for the Other 90%. New York: Smithsonian Institution.

Smith, K. H., J. D. Webb, and B. T. Williams (2010) Just Below the Line: Disability, Housing, and Equity in the South. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press.

Sommer, R. (1969) Personal Space: The Behavioral Basis of Design. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Steinfeld, E. and J. Maisel (2012) Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Steinfeld, E. and J. White (2010) Inclusive Housing, a Pattern Book: Design for Diversity and Equality. New York: W. W. Norton.

Vavik, T. (ed.) (2009) Inclusive Buildings, Products, and Services: Challenges in Universal Design. Trondheim, Norway: Tapir Academic Press.

Weismann, L. (1992) Discrimination by Design: A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Wright, F. L. (1955) An American Architecture. New York: Horizon.