Bushehr, Iran

BUSHEHR:

The City of History

The City of Passion

The Old Friend of the Sun

The Land of Industry, Fishing and Commerce

Bushehr, with its architectural and urbanistic themes dating from the Elamite era of c.2,000 BC, through to the civilization of the Sassanid dynasty and then to its cosmopolitan image of today, is a port that plays an important role in the commercial relations of Iran.1 As the capital of Bushehr province, it is located on the Persian Gulf on a vast plain along the coastal region of western Iran. The city lies directly across the Gulf from Kuwait. Bushehr is represented both by historical continuity, with its old city reflecting Iranian Islamic identity, and by the image of change, due to the presence of international commercial facilities, trading ports, military bases, nuclear power plants and various contemporary buildings. Continuity and change are opposing yet complementary concepts in a world where global issues and local values have been put on the agenda.2 Bushehr, because of its geographic location with easy access to international high seas, plus its rich resources of oil/gas/minerals, and its extensive plantations of palm trees – as well as its various tourist attractions – takes full advantage of its valuable economic potential.3 These geographical and cultural advantages define its idiosyncratic identity, defining thus the configuration of the city.

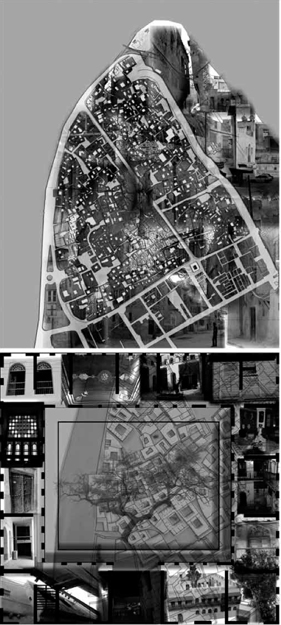

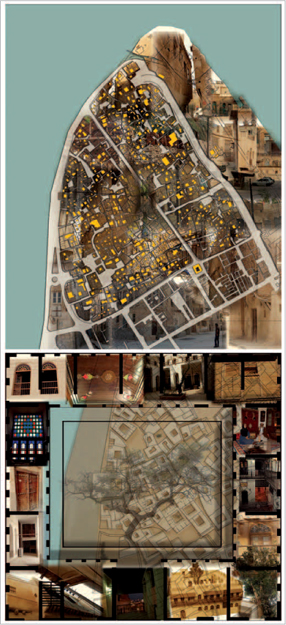

This urban identity can be readily experienced in the Old Quarter of Bushehr, where there are many examples of traditional Persian Gulf architecture from the period from 1870 to 1920, including ecologically satisfying housing settlements with unique spatial configurations rooted in Iranian Islamic identity. The Old Quarter represents the spirit of time and space, creating an ‘aura’ that can be experienced as having certain physical factors (narrow streets, rhythmic arrangements of openings, displacement of solids and voids at different scales) as well as the psychological, social and mental forces which are an integral part of lived space. In this context, we will aim in this chapter to interpret the environmental potentials of Bushehr as a narrative with its visible and invisible dimensions emerging from a continuous unfolding of overlapping spaces, materials, technologies and details. Beyond the city’s physicality, we have tried to read the environment as a place of events and activities that represents a tension between reality and possibility. For our research, a structure of meaning was composed by unfolding the mutual relationship of interdependent elements such as urban identity, economics, ecology, neighbourhood, public space, and the act of belonging both to Iranian Islamic identity and being a Persian Gulf city in a global world. Although this interwoven whole is like a patchwork of traces constituting a series of spatial images, all our investigatory photographs were deciphered through documents, maps, aerial images, urban master-plans, and statistical data provided by the municipality and regional government. These superimposed images and written documents, including our own notes and urban traces grasped during this journey of discovery, provide access to deeper underlying questions about Bushehr. From this, a broad picture of the city emerged which allowed us to discover these new relations: we have sought to articulate how the network relations of the city are perceived as ‘legible’, how Bushehr is read in political, social and economic terms, and how the city’s image might be represented and promoted in marketing terms.

Our on-site period of personal observation and discovery, carried out without any prior hypothesis or prejudice, helped also to establish the research methods for our visit to Bushehr. The aim was to read the city as a narrative in all its dimensions, hence allowing us to understand its complexities. For example, Michael Axworthy has drawn attention to the apparent paradox that Iran and Persia are the same country.4 The image conjured up by ‘Persia’ is one of romance: roses and nightingales in elegant gardens, fast horses, mysterious, flirtatious women, sharp sabres, carpets with colours glowing like jewels, poetry and melodious music. However, in the clichés of western media representation, the term ‘Iran’ has a rather different image: frowning mullahs, black oil, women’s blanched faces peering, not to their best advantage, from underneath black chadors, grim crowds burning flags and chanting ‘Death to …’! It is possible to understand such a paradox when experiencing Bushehr, since it takes its roots from the religious thought of ancient Iranians known as Zoroastrianism (from Zarathustra, or, in Pahlavi, Zardusht or Zardukhsht). This religion was based on the opposition between order and chaos, good and bad, truth and falsehood, as manifested in the thought, speech, and activity of gods and men. This dualism was also reflected in the configuration of the typology of the houses and the urban pattern, thereby creating its ‘aura’. The aim of this chapter is, therefore, to discover the architecture-of-city/city-of-architecture with this specific ‘aura’ of Bushehr, exhibiting some traces that still today reflect its cultural, social, ecological, spatial and temporal relations.

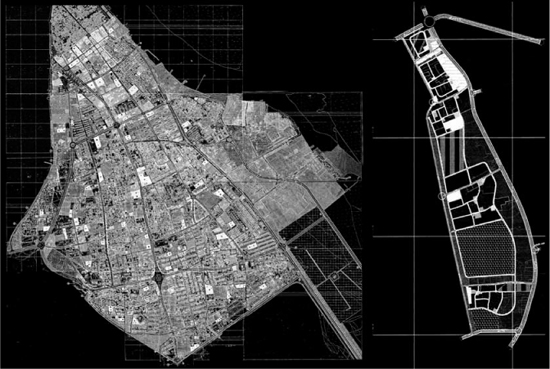

This area has intentionally been left blank. To view Figure 12.1 as a double-page spread, please refer to the printed version of this book

GENERAL ISSUES COMPOSING THE ‘BIG PICTURE’ OF BUSHEHR

Bushehr covers an area of 1,442 km2, which means it occupies approximately 6 per cent of the entire province, and possessed a population of 205,297 people at the time of the 2006 census (estimates are that the figure has since risen to around 225,000). Bushehr is one of the most important ports and transport hubs in the Persian Gulf region. It has a large international airport, and highways connecting it to Ahvaz to the north-west and to Shiraz inland to the east. A secondary coastal road links Bushehr to Bandar Abbas in the south-east of Iran.5 Furthermore, the Shiraz-Bushehr railroad joins this province into the Iranian railroad network, facilitating land-based distribution to and from the province. The city itself is now brutally divided into two by a large military base and by Bushehr’s airport. The centre is located to the north, embracing the Old Quarter, while the industrial part – considered as a developing area in Bushehr Municipality’s current master-plan – sits slightly to the south.

12.1 Geographical location of Bushehr at different scales

12.2 Current municipal master-plan for Bushehr

This master-plan was prepared by the local authority in 2008, and explains how the city intends to grow towards the east and south-west. Individual housing settlements will be spread amongst the palm groves and other green areas, and small industry is to be kept segregated from facilities such as schools, health centres and coastline recreational areas. Extensive maritime facilities, industrial buildings and nuclear power plants have influenced the development of Bushehr over time, providing opportunities as well as threats. While these more global facilities provide wealth and power for the city, they may also become a threat whenever the balance is not so well defined between global and local issues. Bushehr doesn’t appear to be affected by the current international economic downturn, since the Islamic economy, being effectively ‘closed’, is not integrated with the global economy.6 This degree of separation that prevents global developments from affecting Bushehr’s economic growth can also be considered as an opportunity in terms of its independence.

Bushehr is of course one of the chief ports of Iran, lying at a distance of 1,218 km from the capital in Tehran. It is often called Bandar-e Bushehr because it has both a fishing port and a commercial port. The main reason for establishing these port facilities was the strategic location of Bushehr; in that it is built out into the sea on a peninsula in the shape of an anchor, providing natural protection for ships and boats in its harbour. Bushehr, which acts as an export point for farm produce from the neighbouring fertile Fars province, has long played an important role in the commercial affairs of Iran. Moreover, due to its special geographic location and notable wealth, representatives of foreign companies and foreign consulates – including Britain, Germany, Russia and the Ottoman Empire – were located in the city, and some of whom erected fine buildings which have been preserved to the present time. Because of its key geo-political role, European colonialists were interested in taking control of the region and the city of Bushehr – not least the British Empire.7 It is possible still to see this British influence on the architecture in the Old Quarter, again making its spatial ‘aura’ unique within the Persian Gulf region. Furthermore, as noted, the antiquity of the historical region dates back to the Elamite era, two millennia before Christ, when Bushehr was known as Lian.8

Bushehr, however, remained economically depressed until the 1960s, when the Iranian government initiated a major redevelopment program. In 1975 the government, in cooperation with a German company, began building a nuclear power plant at Bushehr some 12 km from the centre. This facility was only partially completed when it was bombed by Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988). In 1995 Russia signed an agreement to finish the plant and to supply a light-water nuclear reactor. Although the agreement called for the spent fuel rods to be sent back to Russia for reprocessing, the USA has expressed concern that Iran is reprocessing the rods itself to obtain plutonium to make nuclear bombs. The previous President of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, backed by most of the Muslim clergy, followed a somewhat lonely path of resistance to the global influence of western values, and in particular to that of America. This resistance might have been praiseworthy in itself, had it not been for the suffering and oppression, the dishonesty and disappointment that also followed.9 However, there is a misguided belief by many in Iran that this direct opposition to western values is the way to stop the inevitability of development on a westernised model in the Middle East, but this fails to see that these tensions offer both opportunities and threats. As long as there is no balance between local values and global issues, then by simply closing all doors to the global community in accordance with rigid rules of Islamic doctrine, all the opportunities created by this resistance are transformed into threats. It also fails to see that Bushehr has local power precisely because of its geo-political position – its nuclear power plant is capable of generate over 1000MW of electricity, plus there are plentiful gas supplies – and this in itself creates a dynamic balance between the so-called tension of the local and global. In other words, the very ‘locality’ of Bushehr can be used as a powerful tool within the globalised world.

During our meetings with the Governor of Bushehr and other government authorities, they confirmed that the current global economic crisis isn’t affecting the economy of Bushehr, nor are Iran’s political difficulties, since the Iranian Islamic economy is kept independent from the Islamic judiciary.10 Although foreign investment in Bushehr is still increasing, according to the Governor, the city is being preserved as a recognition of its idiosyncratic Iranian Islamic identity, something which is based neither on capitalism nor on communism. Iranian Islamic identity, which draws its roots from ancient Persian and more recent Iranian cultures, has been hugely influential on the city’s architecture. Today’s urban designers in Bushehr Municipality seem to be well aware of their social responsibility and environmental sensibility: high-rise buildings are simply not allowed, and all contemporary buildings are required to be designed on a relatively humanistic scale.

Because of Bushehr’s attractive geographical location as a port, and its proximity to target markets, industrial infrastructures and marine products, the city is clearly attracting a good deal of foreign investment. Bushehr’s industries include seafood canneries, food processing and engineering. This is the background for significant opportunities for investment in various other sectors including oil industries, gas and petro-chemicals, mineral processing, and growing dates, among others.11 Yet despite these promising future developments, unemployment in Bushehr today is sizeable, around 24.2 per cent of the workforce; this is partly as a result of a sluggish economic performance, but also because of a dramatic demographic growth over the last two decades. According to 1999 statistics, Bushehr’s investment value in industry was only 0.3 per cent, but since then investment in both the industrial and tourism sectors in the city have increased, mainly due to globalisation. Accordingly, the human development index in Bushehr was 70 per cent, whereas the human poverty index was 21.7 per cent.12 In terms of religious belief, around 90 per cent of Bushehr’s population are Shi’ite, with the remaining 10 per cent being Zoroastrian, Christian or Jewish (while the latter are very few in number, Iran curiously has the largest Jewish population of any Muslim-majority country). Historical documents show that prior to the arrival of Aryans in Iran, Bushehr was the residence for many different tribal groups and ethnic communities.13

This area has intentionally been left blank. To view Figure 12.4 as a double-page spread, please refer to the printed version of this book

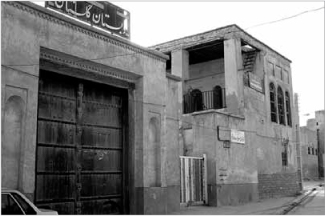

12.3 Saadat High School, Bushehr

Modern Bushehr was the first city in Iran to introduce lithography, and it also developed new industries such as ice-making and electrical production well before many other Iranian cities. The people of Bushehr were amongst the first Iranians to become acquainted with magazines and newspapers, a number of which were printed and published in the city. Education has therefore also been a priority among the people of Bushehr, and the ratio of educated population remains high compared to the rest of the country. There are many buildings consecrated to education in the Old Quarter: one such example is Saadat High School, built in 1899, and the first modern school in all of southern Iran. It was designed by Moin Altujar Bushiri. Many new buildings in a more contemporary architectural style are built as cultural centres, and also provide religious education within their walls. However, with so many of these unauthorized schools now providing religious instruction, we were told by a member of Bushehr Municipality that the education system has fallen even further back than it was at the beginning of the 20th century: a clear criticism of the present education system. Bushehr today has four colleges and universities: the Persian Gulf University, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University of Bushehr, and Iran Nuclear Energy College. All of this points to the potential of contemporary architecture in Bushehr, full of contradictions and complexities. Both concrete and steel construction techniques are now being extensively used for new housing and office buildings, as part of a familiar global context.

12.4 Various cultural centres around Bushehr

12.5 The spatial character of Bushehr’s urban pattern and housing typology

DISCOVERING BUSHEHR’S OLD QUARTER VIA ECOLOGY14

The Old Quarter of Bushehr was built from 1810 next to the port, creating one of the rarest and most superior types of coastal architecture in the Persian Gulf region. Thus besides its archaeological relics and historical monuments, there is a high standard of 19th-century architecture in the city. The pattern of settlement in Bushehr’s Old Quarter has a unique character with its narrow streets feeding sequentially into squares, creating a rhythm of opening and closing; in other words, its urban character depicts enclosure and spaciousness in a similar way its houses. Furthermore, one of the most striking features of Bushehr is its relationship to water. Since the city sits on a peninsula, the sea surrounds the land and can be seen from every point in the Old Quarter. The topology of the old city and its architecture relate to each other in visible and invisible ways. The result is spatial paradoxes of exteriority and interiority, spontaneity and predictability, tension and resolution, balance and instability, rhythmic coherence and continuous unity. These opposing but complementary attributes of the Old Quarter provide some clues for the design of togetherness, belonging and wholeness, which are necessary for harmonious social and ecological relationships. All these concepts form multi-layered structures of meaning to facilitate the reading of the city as a narrative, as well as to understand how architecture can be truly site-specific.

The spatial configuration of the streets/voids and the houses/solids have emerged in accordance with Bushehr’s regional, climatic and cultural conditions, through which the Gulf region’s peculiar local spirit brings together man, nature and values of Iranian Islamic identity. Every part of the unified whole relates to the central idea of this identity, which is why the Old Quarter can be considered as an ecosystem in itself, being organized in a way that it takes its roots from multiple layers. It is possible to discover this ‘deep ecology’ while experiencing and reading the city as a narrative. Its narrow streets are channels both for the movement of people and the movement of air. The narrow streets, opening onto squares, are then usually accompanied by a school, mosque or market, acquiring a specific character due to the colour of these buildings. At the end of a period of darkness created by the shadows cast by the buildings, bright sunlight erupts in the square, which then becomes a landmark. Walking along the streets, it is possible to conceive of daylight in relationship to its seeming opposite, shadow – for, as Louis Kahn observed, shadow belongs to light. This power of contrast makes us think about where we are and what is unique and special about our surroundings, due to its spatial character. The most striking feature of Bushehr’s Old Quarter is the fact that the traces of all its buildings could survive just through their perceptual energies.15

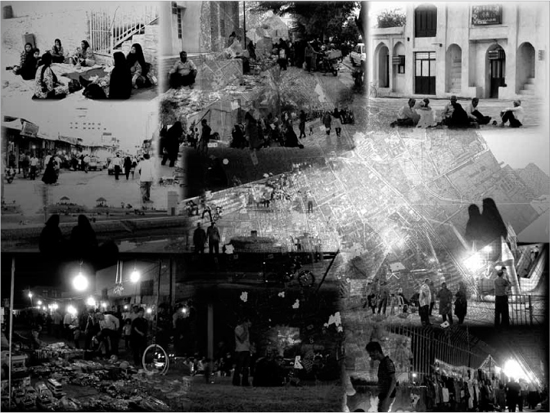

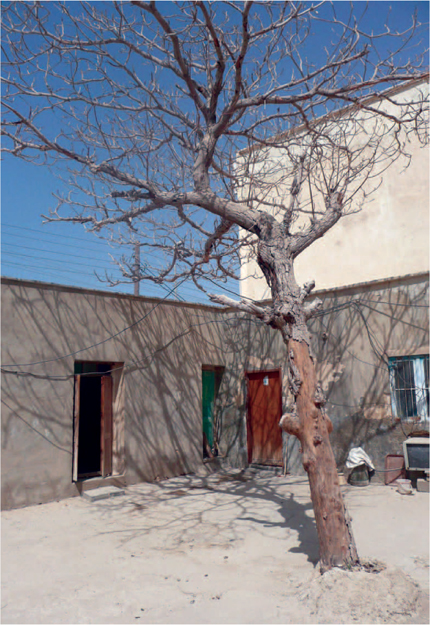

It is obvious that because of the climate, the lifestyle in the Old Quarter is dependent on patterns of outdoor living, hence making the courtyard the most important component in the configuration of its houses. Apart from these hidden courtyards, an outdoor living area up on the first floor has a similar spatial character, which in the corresponding traditional Turkish house is called hayat, meaning ‘life’. Hayat is a place connecting different rooms, hence it being an in-between space; conceptually, it is neither inside nor outside.16 Today the lack of outdoor living areas in modern houses (balconies aren’t real substitutes for these hayat spaces) brings the need for urban spaces where people can come together and socialize. People duly collect together in public spaces in the Old Quarter, especially along the seafront or in courtyards of religious buildings, sitting on the ground without taking into consideration gender differences. Especially on Friday nights, men and women of all ages crowd the streets and other spaces. Open-air markets, entertainment spaces, theme parks, seaside promenades; until the middle of the night, they each play a vital role in the livelihood of the Old Quarter, mixing everyday traditional values with more global influences (see Plate 19).

The modifications and intersections of the volumes between the street level and the first floor of the houses dramatize the composition of solid/massive walls below, which are shaped according to the street. The configurations of the upper floors are based on the spatial organization of the rooms, often exhibiting a variety of triangular bay windows. The narrowness of the streets makes it necessary to arrange these bay windows (called çıkma) in accordance with the relationship between the upper floors and ground-floor storey in a given direction, creating hence another urban visual rhythm. Massive wooden doors with their ornaments increase the dramatic contrast of solids and voids. Balconies, which have 1.5m-high wooden parapets constructed from removable wooden boards, provide privacy and shade the interiors without interrupting air circulation. Privacy is an important concept in Iranian architecture, as exhibited here by the high garden walls, first-floor bay windows and massive ground floor walls. The origins of this concept of privacy indeed date back to pre-Islamic periods. There are many spatio/temporal relations of privacy with hidden meanings in Bushehr that can only be understood by experiencing the city. For example, the entrance doors of many houses have different forms of knockers that produce a different sound, through which the residents can discern the gender of the visitor. The ring-shaped door knocker is used by women whereas the pendulous one is used by men. As another way to promote the separation of sexes, according to the Islamic way of life, the houses are divided into two parts: the birun, situated towards the outside of the house, is for men and their male guests; while the anderun, situated towards the interior, is for women, their female guests and the domestic helpers.17

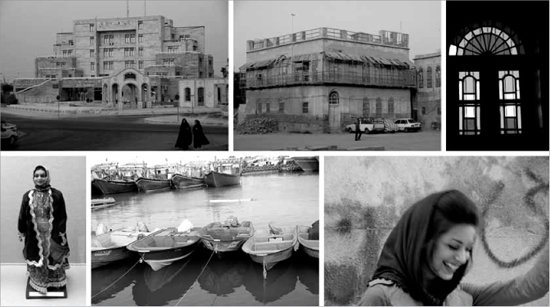

12.6 Everyday life in Bushehr

It is possible to observe how the quality of life is enhanced in the Old Quarter of Bushehr by analyzing its ‘deep ecology’: in other words, the mutual relationships in the urban pattern between cultural values, social organisation, climate, traditional lifestyle and housing configuration. The typology of houses and the urban pattern have similar traces rooted in the idiosyncratic Islamic way of life. Wind-catchers, called badgirs, are located at the top of the buildings to provide air circulation inside the buildings as a natural cooling system, as distinct from the air-conditioning devices of today.18 Courtyards, along with other local building techniques, exhibit the interweaving of lifestyles and the physical environment that constitutes the local ‘ecology’.19 Historic water canals in the middle of the street are configured with drainage wells. Today, however, due to the growth in population and increase in new buildings, the city’s drainage system doesn’t work nearly as well, and these water canals have become open sewers which aren’t embedded in the ground, since they are at the same level as the sea.

12.7 The textures and rhythms of the city

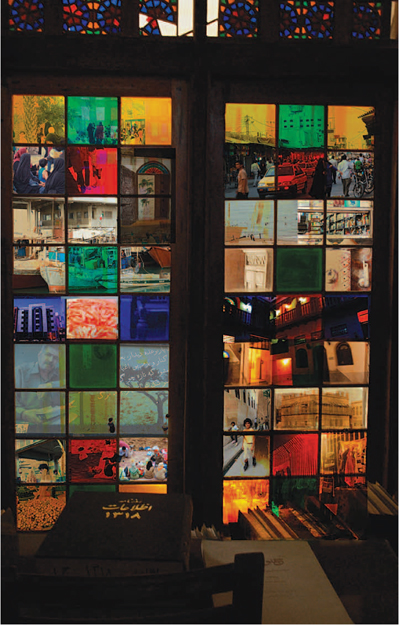

The ‘ecology’ of old Bushehr is not limited to environmental factors, but also perceptual and social relations for the benefit of human beings, such as experiencing the textures and rhythms and indeed vibrant colours of the city. For example, the cool blue-green of the sea creates a real contrast with the buildings in the Old Quarter, built out of limestone covered by mud plaster and painted with warm colours. This unique technique of using limestone with mud plaster applied over it to construct the houses creates a dramatic effect; furthermore, the limestone provides good insulation due to its layered and porous structure. Lime mortar is also used for insulating water in cisterns. Additionally, this colourful built environment becomes a background for women wearing black chadors; moreover, occasionally seeing women in colourful dresses walking next to the black-clad women also creates a signal contrast. Colourful windows, called orsi, which give a mysterious atmosphere and prevent mosquitoes from entering, have become the symbol of Bushehr. They refer openly to an Iranian Islamic identity, which is also represented by colourful handicrafts and fishing boats.20

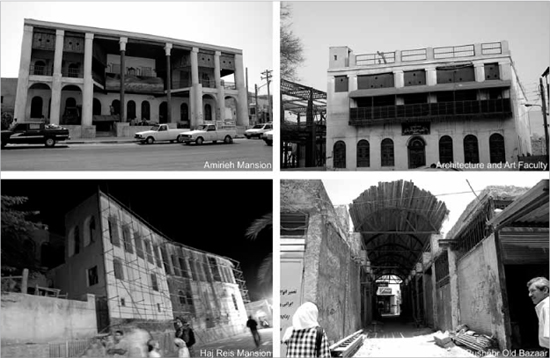

The Old Quarter of Bushehr has been well supported by Iran’s Building and Housing Ministry, which has spent the equivalent of $30 billion on regeneration work. The ministry has several incentives for redeveloping this area through new investment projects, one of these being to restore the coastline wall and transform it into a recreational area. In the regeneration of the Old Quarter, an ecological approach to understanding the whole physical and natural properties is of considerable importance for creating a contemporary livable environment. The past should not be disregarded, and the wheel reinvented, every time a new domestic environment is designed in the name of sustainability. Sustainability can instead best be defined as an integration of local values that require continuity and global issues that relate to change. As a result, a range of cultural, social, perceptual, ecological issues can be related to each other to form a unique ‘aura’. Yet in spite of the current regeneration agenda of Bushehr Municipality, the restoration of some buildings is being undertaken without proper consideration of the environmental sensibility needed to create balance between the new and old. Other interventions, however, are much more promising. For instance, the steel-frame construction being built as an extension to a building in the Old Quarter will act as the new school of architecture when it’s completed, adding a contemporary mark without dominating the general image. Complementary forces can hold together the traditional and contemporary configurations on behalf of the principle of sustainability.

12.8 Regeneration scheme for the Old Quarter of Bushehr

12.9 Ongoing regeneration work in the Old Quarter

12.10 Major edifices currently being restored

12.11 Omaret-e-Malek, as now owned by M. M. Malekaltujjar

12.12 Sheikh Hossain Chahkutahi Tomb

Several fine edifices in the Old Quarter, located along the seafront, have been restored for use as official governmental buildings.21 Influential facets of Persian identity can be experienced both inside and outside of these grand mansions, in which the typical schema of the courtyard as a common space provides access to all the rooms on the ground floor. Coloured glass windows, wooden doors with ornaments, wooden-beam floors, and other details provide an in-between spatial character for the contemporary reuse of these buildings. Elsewhere, however, a huge derelict building called Omaret-e-Malek, which was built by French architects at the end of the Zand dynasty, is still waiting to be renovated. It is currently occupied by homeless people who are unaware of its value. An extension to the Shaikh Hossain Chahkutahi Tomb is a brutal example of historic preservation with no awareness about environmental sensibility or social responsibility. Concrete columns are being plastered around the existing building, depressing and dominating its original power; one can just imagine how the tomb will ‘disappear’ altogether once construction is completed. Other cultural changes we observed while in Bushehr may also pose a threat to its cultural heritage, since a lack of environmental awareness may be giving rise to fakery.22 Interference with the historic environment requires the inclusion of 21st-century life without losing the ‘aura’ and historical testimony that is being passed from past to present to future. Bushehr represents cultural codes and urban traces that are hidden and waiting to be rediscovered, and so its old buildings should not be ‘frozen in time’.

QUESTIONS OF IRANIAN ISLAMIC IDENTITY OF BUSHEHR WITHIN GLOBAL CULTURE

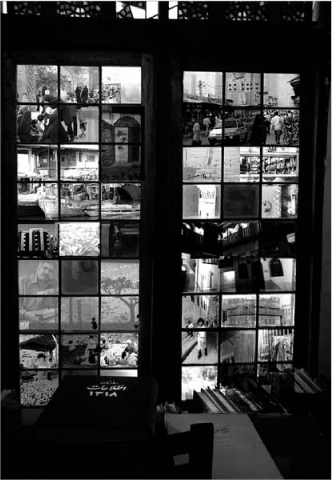

Today, Iranian Islamic identity is a phenomenon of the ‘congregation society’ type, wherein a close interpenetration of state and society, representation and administration is required. A tendency towards expressing cultural identities exists amongst different political/economic ideologies across the world today, and each cultural sphere needs to generate its own technological systems as a consequence. Iranian Islamic identity needs to be deconstructed in relation to recent developments in the globalised world so that this identity can more easily become materialized. Under the influence of marketing strategies within the context of globalization, cultural dynamics can be said to exist in the exchange market. In order to avoid falling into the trap of marketing ‘locality’ in Bushehr as a meaningless commodity, its architects, urban planners, political authorities and decision makers should be aware of the potential of the idiosyncratic features of Iranian Islamic identity. It is for instance possible to see the fragments of the global world in Bushehr just from the design of a window in its Iranology Institute, which manages to symbolize locality and reflect a broader Islamic sensibility.

12.13 Window of the Iranology Institute in Bushehr, reflecting some fragments of Iranian Islamic identity

Preserving the ‘locality within globalization’ refers to dynamic spaces that flow, instead of static places in which the conflicts between the local values and global issues only create tension and resistance. Although global issues represented by change and local values requiring continuity constitute a paradox, they can also complete and nourish each other. Locality is not only a process that constitutes the ‘other’ of globalization, but also a specific counter-move to transform the configuration of a city like Bushehr. Iranian Islamic identity thus needs to be rediscovered through the globalization lens; in lights of this deconstruction of Iranian Islamic identity, old spaces with new ideas can create unique identities by oscillating between change/global and continuity/locality (see Plate 20).

Hence the Old Quarter of Bushehr has multi-layered and intangible meanings just waiting to be discovered. To discover Bushehr’s potential to create new connections, first the city has to be read as a narrative with its unique temporal and spatial relations drawn from the power of geography, history, cultural variety, social relationships and lifestyles in relation to each other. The most important issue is to become aware of cultural codes, which are archetypes; however, they shouldn’t be transformed into stereotypes. In the Old Quarter, windows with coloured glass can be considered as cultural archetypes produced by specific hand-made techniques. Whenever they are re-used in new buildings, they lose their invisible character because of mass production, becoming a stereotype. Superficial imitation and visual fakery can emerge in new architecture if motivated by marketing strategies, and not by referring to the collective memory which has for so long played a crucial role in building Iranian Islamic identity. Ahmedi draws attention here to the role of narrative, which is defined as an event-network that enables us to understand how identity is constructed over time and place.23 At the conceptual level, narrative functions as a meta-code transmitting the essence of historical and cultural events.

Cultural identity here, having its roots in ancient Persian civilizations and Zoroastrian values, is specific to the Iranian part of the Gulf region. Bushehr is thus different from coastal cities in other countries in terms of its historical, religious, political, economic, psychological and social networks. Besides, the single-party government in Iran, with its congregational religious ideology, is holding up ways for new developments by pressuring the press and mass media into conformism. To understand such as complex network system as exists in Iran, with all its contradictions, things cannot be reduced to the knowledge provided solely by analytical research. Understanding the whole phenomena as a network system requires us also to look around the margins at senses affected by perceptual experiences, and which can create multiple new paths and connections.

12.14 Old Quarter of Bushehr within the context of globalisation

According to the Governor of Bushehr, the Islamic revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini was the antidote in terms of maintaining Iranian Islamic identity. In the Governor’s view, although Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was an admirer of western culture and wanted to destroy Islamic values, he was not successful. Throughout history, Persian (and then Iranian) culture was never greatly influenced by European expansionism, even if the two were in close contact through commercial relations. According to the Governor, the democracy brought in by Khomeini has since played an important role in creating a unique cultural identity based on inexhaustible contrasts. He also emphasized that the Iranian Islamic Republic, by not losing its sense of cultural identity, acts as a role model for other developing Middle Eastern countries. But this, however, is also the paradox of being a closed society. By not imitating western culture, and by strenuously maintaining a sense of locality, it means that Iran has not been so able to be involved in the globalised world, and thus has missed out on opportunities for information exchange and commercial benefits. For instance, Bushehr remains unaffected by the global economic crisis, but similarly it has not yet been able to profit from international booms either. A balance between global issues and local values is needed to get beyond this paradox. Bushehr, sitting on the Persian Gulf coast, has the potential to create a new balance through the power of its natural resources and cultural heritage. These potentials will surely also help the ongoing development of its cultural identity, maintaining its locality within a global context. During the 21st century, Iranian Islamic identity will have to be deconstructed and continually remade, and its rethinking can represent both change and continuity without losing its ‘aura’.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

This chapter focused on a holistic understanding of Bushehr in light of Iranian Islamic identity and how this has influenced the configuration of the city – with an emphasis on the need to conceive of future developments through the concept of ‘locality within globalization’. Overlapping ideas gained by reading the city as a narrative were strengthened by photographic images we took to show thematic relations. Thus the research process proceeded in a non-linear form, having no beginning or end, so as to remain open to new ideas. This non-linear process, in which all the contradictions were brought together in relation to each other, allowed us to trace the resistance to the global influences of western values while also responding to changes in the city. One can regard this as a reflection of a continuing sense of Iranian uniqueness and cultural significance.

Furthermore, global culture will absorb locality if the process doesn’t contain tensions and antagonism, with the locality needing to open up doors for new cultural/spatial relationships within the context of globalization. Cultural identity can thus be defined as a tension between the sameness and difference caused by global fluidity. Iranian Islamic identity should thus be read in accordance with the contemporary and revolutionary possibilities offered by the tension between local and global. Although Iran is a country with an ancient tradition of monarchical splendour, the revolutionary Islamic Republic also has many paradoxes which can be seen as offering the potential for global fluidity.24

By considering sustainable living conditions composed of a combination of change and continuity, architecture and urban design should seek to promote cultural development through global fluidity. The ‘deep ecology’ movement does not propose an entirely new philosophy, but instead revives an awareness which is part of our cultural heritage. The growth of this new awareness relies on the maxim: ‘Think globally and act locally’. By looking at the issue from a range of perspectives, it is possible to discover the multi-layered meaning of Bushehr both in its visible and invisible characters; in other words, through the mood of the city. It is possible to create a new Islamic Iranian identity by preserving Bushehr’s locality within globalization, if the architects and urban designers, who are responsible for forming livable environments for the 21st century, read the city as a narrative. By doing so, Bushehr as an important Persian Gulf city – with its long cultural heritage, natural resources and idiosyncratic position in the Iranian Islamic worldview – will assimilate its own continuity and change to show how to preserve ‘locality within globalisation’.

NOTES

1 Iran is divided into 30 provinces that appointed governors administrate. Bushehr is one of these, and has an area of 23,000 km2, being located in western Iran on the eastern shore of the Persian Gulf. The province consists of nine counties – Bushehr (capital city), Tangestan, Jam, Dashti, Dashtestan, Dayyer, Deylam, Kngan and Genaveh. There are then 22 districts, 29 smaller towns and 43 rural districts, all with a population of 826,412 people according to the 2006 census. See for example: ‘Bushehr Province’, Irano-British Chamber of Commerce, Industries and Mines website, http://www.ibchamber.org/Magazine%2015/3.htm (accessed 21 August 2009); A. Barzgar, Bushehr Province: Land of the Sun (Bushehr: Bushehr Municipality, 2007); ‘Bushehr’, Hosban News website http://www.hosban.ir/module-pagesetter-printpub-tid-1-pid-16635.html (accessed 22 August 2009); ‘Cities of Iran: Bushehr’, Iran Chamber Society website, http://www.iranchamber.com/cities/bushehr/bushehr.php (accessed 1 September 2009; Iranology Association and Pejvar Advertisement, Old Bushehr in a Mirror of Pictures (Bushehr: Iranology Association, n.d.).

2 Semra Aydınli, ‘Continuity and Change in the Image of Istanbul’, in Martin Edge (ed.), Old World – New Ideas: Environmental and Cultural Change and Tradition in a Shrinking World, Proceedings of the Environmental Design Research Association Conference (EDRA 32/001), Edinburgh (2001), pp. 22–26.

3 Bushehr Investment Committee with Commercial Cooperation Organisation, The Focus of Investment Opportunities, Bushehr Province (Bushehr: Bushehr Investment Committee, 2009).

4 Michael Axworthy, Iran, Empire of the Mind: A History From Zoroaster to the Present Day (London: Penguin Books, 2008).

5 Bushehr is connected to the other parts of Iran by three connective axes. The first one passes through Bushehr-Borazjan-Kazeroun and goes on to Shiraz, which is the first and major axis for land transportation to the central areas of Iran. This axial route is about 320 km long. The second is the connective axis of Bushehr-Mahshahr-Abadan, which runs parallel to the coastline of the Persian Gulf and is 690 km long. The third one connects Bushehr to Kangan and Bandar Abbas, and is 921 km long. See: ‘Bushehr Province’, Irano-British Chamber of Commerce, Industries and Mines website, http://www.ibchamber.org/Magazine%2015/3.htm (accessed 21 August 2009).

6 Since the Islamic Revolution and the deposition of Shah Mohammad Rezain 1979, as a result of embargos from countries such as the USA, Iran has become a virtually closed economy.

7 The Portuguese invaded the city of Bushehr in 1506 and attempted to take the place of the Egyptian and Venetian traders who were dominant in the region. Since Bushehr was the chief seaport of the country and the administrative centre for all of Bushehr province, it was later used as a base by the British Royal Navy in the late-18th century, becoming after that an important commercial port.

8 During the 1st and 2nd millennia BC, the peninsula of Bushehr was a thriving and flourishing seat of civilization called Rey Shahr. Many relics have been found from the Elamite era and the civilization of Shoush (Susa). The structures and artifacts of Rey Shahr are said to be related to Ardeshir of the Sassanid dynasty, and indeed Rey Shahr was formerly known by the name of Ram Ardeshir. Over the passage of time the area and its main city came to be called Rey Shahr, and hence the name of Bushehr today. See: ‘Cities of Iran: Bushehr’, Iran Chamber Society website, http://www.iranchamber.com/cities/bushehr/bushehr.php (accessed 1 September 2009).

9 Axworthy, Iran, Empire of the Mind.

10 In the course of researching this chapter, several meetings were conducted with the Regional Government, Mayor, Head of Iranology Centre, Head of Anthropology Museum, and other figures in key government offices.

11 Key examples of investment opportunities in Bushehr are infrastructural, such as creating access to Bushehr International Airport, or access to port facilities for unloading and loading, or maritime terminals for freight and passenger transport to other Persian Gulf states. The presence of huge oil and gas fields in the province has led to the consideration of potential marine-based industries in Bushehr, such as constructing marine structures and investing in shipyards to build and repair fibreglass and timber vessels, etc. There are also potentials and capacities to invest in air/ship/land transportation of goods, and in the fishing and palm-growing sectors. See: Bushehr Investment Committee, The Focus of Investment Opportunities, Bushehr Province.

12 Hamid Ahmedi, Iran: Building National Culture (Istanbul: Metis Books, 2009).

13 From historical evidence, in addition to native people and various Mediterranean races settling in the Bushehr province, other ethnic communities such as Dravidians, Jews, Elamites, Sumerians, Nordics, and Arabs also lived in the region. Afterwards, especially during the establishment of the provincial cities, and in particular Bushehr, other ethnic and tribal groups from the Iranian hinterlands migrated to the area, and this multi-ethnic mixture resulted in the present ethnic characteristics of Bushehr Province. Among the later arriving groups were Lurs, Turks, Behbahanies and Dehdashties. See: ‘Bushehr Province’, Irano-British Chamber of Commerce, Industries and Mines website, http://www.ibchamber.org/Magazine%2015/3.htm (accessed 21 August 2009).

14 Here we are specifically referring to the principle of ‘deep ecology’, which is widely supported by modern science and in particular by the new systems approach. The ‘deep ecology’ movement recognizes that achieving ecological balance will require profound changes in our perception of the role of human beings in the planetary ecosystem. According to this more holistic approach, not only physical environmental conditions are at stake in ecological approaches: social, cultural, political, economic issues, working in interaction with each other, are also the crucial for understanding and describing ecological problems. See, for instance: Fritjof Capra, The Turning Point (London: Flamingo, 1983).

15 The Old Quarter of Bushehr consists in fact of four quarters: Kuti, Behbehani, Shanbedi and Dehdashti. Kuti, which is located on the coast at the head of the peninsula, was begun 150 years ago.

16 Dogan Kuban, Turk Hayat’li Evi (Istanbul: Eren Yayincilik, 1995).

17 This is covered well in the various papers written by Sanjoy Mazumdar and Shampa Mazumdar. See for instance: Shampa Mazumdar & Sanjoy Mazumdar, ‘Religious traditions and domestic architecture: A comparative analysis of Zoroastrian and Islamic houses in Iran’, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, vol. 14, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 181–208.

18 ‘Badgir’ is the name for a Persian architectural element which in English is called a wind-catcher; and is one of the many examples of energy-efficient designs from the ancient world. This Iranian term for a wind-catcher refers to a tall chimney-like structure which projects above the roof of a building to expel warm air in the day and trap cooler breezes at night. See: Ahadollah A’zami, ‘Badgir in traditional Iranian architecture’, Proceedings of International Conference on Passive and Low Energy Cooling for the Built Environment, Santorini (May 2005), pp. 1021–1026.

19 Qanat is the local Iranian name for underground water transportation channels.

20 In respect to its cultural identity, handicrafts have long had a leading impact on the life style of villagers living in Bushehr. Due to the limitations of the agricultural sector and seasonal unemployment, most of the habitants of rural areas try to benefit from raw materials naturally available to them as a means for earning more income, and to produce items such as carpet, gabbeh (the most outstanding domestic handcraft in Bushehr, a long wafted pile-less carpet weaved by wool mixed with goat hair), aba (men’s loose sleeveless cloak), gelim (short napped coarse carpet), straw-mats, ceramics, giveh (light cotton summer shoes), buckets, hampers, baskets, nets, textiles and sewing products. In addition, traditional shipbuilding is one of the oldest and most important handicrafts in Bushehr, dating back to the time of Nadir Shah. The main material used for shipbuilding is teak imported from India, and then used with other materials from Iranian sources. See: ‘Bushehr’, Hosban News website, http://www.hosban.ir/module-pagesetter-printpub-tid-1-pid-16635.html (22 August 2009).

21 The Iranology Building, Anthropology Museum, Customs Building and Art and Architecture School are some examples of buildings which have been restored; in stark contrast, the British Consulate, Haj Reis Mansion and Old Bazaar are examples of those not yet restored.

22 The types of cultural modifications to historical buildings which can be seen around Bushehr vary over a wide spectrum from fakery to imaginativeness.

23 Ahmedi, Iran: Building National Culture.

24 For the first ten years after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the fact of having a charismatic religious leader (Ayatollah Khomeini), plus a widespread application of populist politics, religious symbols and concepts – accompanied by open hostility to external enemies such as Iraq or the USA – helped to sustain the Islamic identity of the new Iranian state. In the following decade, various developments giving rise to changes in the attitude of urban citizens tended to undermine the religious and revolutionary aspects of political, social and economic life, bringing about a division of identity amongst the people. This issue of what is Islamic identity has ever since been one of the basic political conflicts in Iran. The information that we obtained from various sources in Bushehr shows that besides being underdeveloped in economic and technological terms, a growing urban population and poor urban management policies are working to the detriment of the urbanization process in the city.

17 Houses built by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company for local workers in Abadan, Iran

18 Brickwork and glazed tiles in the hybrid dwellings of the Bawarda Garden Suburb, as reminiscent of central and southern Iran from the 1930s to the 1950s

19 The urban pattern and housing typology in Bushehr, Iran

20 Window of the Iranology Institute in Bushehr, reflecting some fragments of Iranian Islamic identity

21 Traditional house in Banak, Iran, with courtyard built out of local materials

22 Shop window in a brand new store in Kangan, Iran

23 The abandoned casino on Kish Island, Iran

24 Wind-towers on the reconstructed Ab Ambar well on Kish Island, Iran