1.3

Charles Garnier: Le Théâtre, Chapter 4, Staircases1

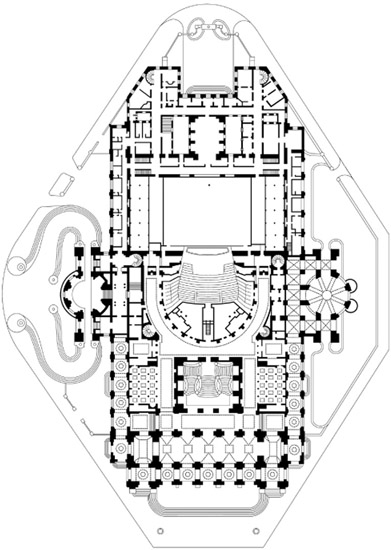

Figure 1.3.1 Paris Opera, principal façade

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

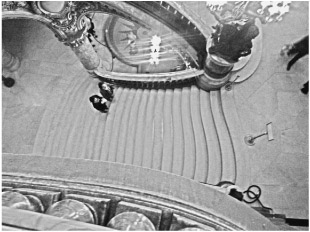

Figure 1.3.4 Paris Opera, a flight of the main stair from above

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

The Paris Opera is Charles Garnier’s masterpiece, but the choice of architect was not a foregone conclusion. Initially, Charles Rohault de Fleury had been commissioned by Louis-Napoleon, but he was displaced in 1860 in favour of the Empress’s favourite Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-duc, who argued for a two-stage competition. This was duly held in 1860–1, and, although Garnier only gained fifth place in the first round, he won unanimously in the second. The foundation stone was laid in 1862, although the building was not completed until 1875, delayed by the Franco-Prussian war and the subsequent political changes.2 Garnier followed it up with a book, Le théâtre, which describes the design and the many intentions behind it in great detail, with chapters on arrival, vestibules, foyers and so on, looking at each in turn. We have taken the chapter on staircases as a representative sample, as there experience of movement is of most pressing concern. It was too long to include in its entirety, and so has been edited down to about half, covering the reasoned choices in designing the main stair but leaving out similarly exhaustive treatments of the secondary stairs and stair cage. Garnier wrote in a florid and rhetorical manner and could be rather repetitive, and so the initially direct translation has been subjected to cuts too numerous to mark, although the customary ellipsis does indicate major excisions towards the end. For an appropriate impression, we preserved in full some of Garnier’s more rhapsodic sentences about the ritual of theatre.

Chapter 4 The Staircases

Here we touch on one of the most important aspects of organising a theatre, not just for the sake of connections and circulation, but to produce an artistic motif that contributes to the general beauty of the building. With most large auditoria in France and abroad a rational composition of stairs is lacking. There are buildings where walkways are well arranged: the Carlo Felice theatre in Genoa, for example, or the Grand Theatre in Munich, which, on each side of a vast vestibule, develops two great ramps of coloured marble reminiscent of those at the Odéon in Paris. There is also the theatre at Bordeaux, whose stair is famous, and some in new Paris theatres. But taken together, almost all theatres are incomplete in having stairs that are small and mean, no larger than the secondary ones. One has to hunt around to find one’s way, and decorative motifs are often missing. So rather than taking them as models, the architect must regret the inadequacy of existing stairs. It is not just the architect’s fault, for the site is often restricted, the programme too rigid, and one must excuse the artist caught up in his operations, unable to exceed strict necessity when an additional generosity was needed. Ever since primitive theatres, the monuments for theatrical display have shown this inadequacy. Little was demanded because people were easily satisfied, and nobody supposed that, independently of the plays presented, the view of grand staircases filled with people could also be a spectacle of pomp and elegance. Without considering any architectural motif, architects sought only a means to arrive in the hall, yet grand and beautiful staircases were not rare in palaces, museums, and even convents. So lack of artistic creativity was not the problem, but rather lack of resources, lack of space, or lack of will on the part of clients.

But now that luxury is extended and comfort sought everywhere, when the departure of the audience is awaited by observers eager to witness an elegant and varied crowd, with today’s facility of communications and the need to satisfy the eyes as well as the mind, the architect faces a need for monumental organisation and large well-placed staircases. In a large theatre there must be no indecision about which route to follow towards entrance or exit, and the motif chosen for effective functioning must also be an artistic motif predisposed towards the splendours of the production and the shimmering splendour of the ladies’ dresses. Let us consider the form and placing of the staircases. We must be guided by practical study of crowd movements and by the desire to develop the art at large scale in a sumptuous way. First general layout: whatever your feelings about the principles of equality, it must be admitted that in a theatre one can never make all seats equally good. If differences in quality exist, differences in seat prices follow, which leads in turn to a difference between the comfortable and the luxurious. This vicious circle is unavoidable, so despite doing all possible to avoid complaints, one is obliged to create several categories of seats, which basically divide between ordinary and luxurious. The most rational method to split the crowd is to follow the seats, so the stairs divide into those serving ordinary seats and those serving luxurious ones. The route for each is defined, and confusion is avoided. I am well aware that some pedantic egalitarians will say this initial division disfavours part of the audience, and that the theatre should belong to all without distinction. I am not sure that any great harm is done to them, but if two or three thousand people are made to pass along the same route, that route will certainly be badly encumbered, and if everybody is treated the same, all are treated equally badly. I do not see therefore that it would achieve any increase in dignity. Since nobody is embarrassed to go to the stalls or to the third level boxes, I see no reason why people should be embarrassed to take a route not shared with those going to the first level of boxes. When in the street I walk on the pavement, I do not feel insulted to leave the central carriageway to vehicles: it is a guarantee of security and makes circulation easier for everyone. Dignity is not involved.

So in any theatre there must be first of all a staircase for luxurious seats, a stair of honour, if you wish, supposing that it belongs not to the persons who climb it, but rather to the position it occupies. Then there must be other flights leading to secondary seats. This is the principal division, but we must attend to the way fashion influences the quality and value of seats, for if categories change, it is not the same with the stairs. They have to remain as constructed, and since they must be useful however the seats are designated, they must not be too isolated from each other, allowing passage from one flight to another to take place easily. Therefore the grand stair of honour should connect with the secondary stairs, so that people can move easily from one to the other.

Moving on to the placing of the stairs, we can assume that the grand staircase should be central, for if set to one side it would serve only one side of seats, and it would constrain persons attempting to move from one side to the other across the crowd in the middle. It is obvious that it must occupy the noble place in a building, following the axis of the auditorium, the vestibule, and the building as a whole. With the grand staircase so placed, the secondary stairs should be laterally placed, that is to right and left of the principal stair. I say to right and to left not to right or left because it is advantageous that the large crowd going to the secondary seats is split to avoid crossings and embarrassment at every level, and indecision about which path to take. Furthermore, because in terms of usage any auditorium should be symmetrical in plan, it is logical that its connections also be symmetrical. When services offered are identical, what is found on the left should also be found on the right, and for all these reasons, following common sense as well as study, one must conclude that the stair of honour should take the centre, with secondary staircases to right and left of it. This starting point can be further fulfilled by study of the arrangement of flights and ease of communication between different routes, and this we must undertake next.

The disposition of flights in the grand central stair can be arranged in various ways, many of which can be effective and monumental. There are four main approaches [partis] under which one can gather all variations; they can be discussed one by one, and this study will show by the variety of their arrangements, that these four partis include almost all grand motifs of stair flights found in practice. The first, offering greatest simplicity, is the straight flight. On arriving at the cage of the stair, one discovers a grand broad ascent and there is no hesitation about where to go. The route is indicated, the way simple, the aspect monumental, the motif frank and accentuated. Leaving enough space to right and to left of the central flight, whether for circulation on the same level or for circulation descending, the cage enlarges, develops, takes on the form of a beautiful vessel, which one can decorate with nobility and splendour. Considering these qualities alone, the big straight stair would be a suitable choice, but one must look beyond first impressions and also study its faults.

Following the custom adopted in nearly all theatres, the foyer, the principal galleries for promenade, should be at the level of the first boxes, that is the piano nobile, where one combines luxury with comfort. This means that to pass from the foot of the first staircase to the first boxes, one must ascend the height of the ground floor to the stalls or baignoires,3 then carry on from the level of the baignoires to the first boxes, that is two levels of ordinary corridors. Now, the minimum height of such galleries in a grand theatre is about 3 metres. This is a bit high for the services themselves, but rather low for the galleries and corridors that surround the hall. It is therefore a compromise, and the height of 3 metres is the average that should be adopted, at least for the lower floors. For a monumental staircase of 3 metres where the steps have to be really gentle one must assume a minimum of 22 steps. With each around 35 cm wide this makes a length of more than 7 metres, so whatever the form of the flight, one must allow for this length. Because the central stair rises two floors, it is indispensible that it should serve in its course the first luxury seats, stalls of the amphitheatre, balconies, or baignoires, which are situated half way to the first boxes. There must therefore be a mid-level landing to let people off to right and left. Another landing is needed at the head of the stair, for one of the indispensible conditions of stairs is that they must not finish without a pause before the entrances; this is not only indispensible practically, but also artistically. For satisfactory proportions these landings require as much depth as breadth, so they should be as deep as the width of the stairs. But since a grand central stair is useless unless it allows easy circulation of the crowd, it needs at least five metres of landing, and again this is the minimum.

This dimension of five metres must therefore be taken up first with the lower landing, then the middle one, then the upper, adding up to 15 metres; to this add the two flights of a further 15 metres, and it produces around 30 metres in all, without taking account of the wall thicknesses of the surrounding cage. Certainly it is not impossible to construct a staircage of this size, and size alone would give a grand effect, but what is more difficult is to find a site to permit such development. Even given the space, developed at this scale, this motif leads to the inconvenience of separating hall from foyers excessively. The inconvenience is but relative, and might be corrected, but there is another problem that seems yet more significant. A grand central stair ending directly at the corridor of the first boxes also pulls the lateral stairs forward and produces a problem of continuity between staircases. For as we saw above, it is important that all staircases inter -communicate, and if they fail in this the fault is felt on every ascension, increasing separation between the connections of seats, an isolation that brings embarrassment. The architect should concentrate on rational and practical aspects before considering any idea of splendour and artistic desire, so if he cannot remedy this fault, he should not hesitate to reject this arrangement which, although furnishing him with a pattern that is easy to study and of a certain effect, commits a significant sin. Art is not complete until the whole programme is satisfied, and, even if it costs the artist a little, he must follow a programme that is both reasonable and reasoned.

The second grand pattern of staircase that can be used and has often been employed to happy effect is that of two opposed flights leaving sideways from a grand central vestibule and ending to right and left of the theatre. The Paris Odéon is so composed, and its appearance is monumental. The grand theatre in Munich, already mentioned, follows the same parti with equally monumental effect. This arrangement does not have the same inconveniences as a single central flight, does not push back the foyer too far, and if the lateral stairs are placed at the extremities of the paired flights, communication between main and secondary flights can be easily managed. Also the two opposed flights form so to speak an amphitheatre between them, grouping persons who ascend and descend in a harmonious manner: a double spectacle in which each is at once actor and spectator. In this parti, then, everything seems of good service, and to allow the artistic manifestation every development and prestige, so one can only approve it in principle as a grand and beautiful arrangement.

But this too is not without inconveniences, for owing to its size, even its grandeur, it has a disadvantage which must be noted. It goes without saying that I am speaking always of a grand theatre where the foyer is at the height of the first level of boxes, where one has to mount two levels to arrive at these boxes, and where the average height of the corridor to the hall is three metres. We have seen earlier that a single central progression established in these conditions had a development of around 30 metres. With two opposed progressions it needs at least twice the space, for the central vestibule needs at least ten metres of width to answer the needs of the two grand staircases. This gives the whole ensemble of the two flights a total dimension of around 60 metres. But, as the greatest width of hall in which performances remain audible is 40 metres, including the salon of the boxes, it results in people having to turn back from the tops of the flights to rediscover corridors to the boxes.

Certainly, if the vestibules or galleries through which one passes on this route are well disposed and generously decorated, it will be no great pity, and the longest circulation will be made easier. But it is illogical to pass the goal before arriving, and it would be better if the arrival took place where it is most convenient. Nevertheless this little inconvenience does not inflict an irredeemable vice on this grand arrangement, which admittedly fulfils the conditions required for easy circulation of spectators and good architectural order. It is even advantageous that at mid-route, at the level of the baignoires, the doorways placed to the right of the first landing will meet the corridors at a convenient point, and here again logic is satisfied.

But another drawback is that the staircases impede circulation from the hall to the foyers, so either one must pass around the edge, or cross above the central vestibule of the ground floor. Both cases are problematic, for if one goes round the edge one must leave the boxes, pass along the ascending flight, and traverse the outer landings to go to the foyers. If instead one passes above the central vestibule of the ground floor, the circulation is direct and the goal well indicated, but it does introduce a further inconvenience. If the vestibule of the ground floor is cut off at the floor of the foyer, it divides the collection of stairs in two, so instead of one open cage, wide and monumental, one has two cages distinct and separated, which however grand and well decorated, can never have the simplicity and nobility of a single cage. The motif is deflowered, unity destroyed, and the great artistic advantage of this double arrangement is almost annihilated by this division.

There is a third parti sharing aspects of the previous one, which has perhaps a certain advantage. The opposed flights, having arrived at the level of the baignoires, instead of continuing to the level of the first boxes, turn back towards a grand landing placed above the central vestibule. The arrival of the stairs is closer to the boxes, and as the staircase takes less space across the width of the theatre, circulation from hall to foyers is more direct, so the faults noted for the second parti do not apply to this third one. There is advantage here, but communication with the secondary stairs is at the level of the baignoires, so people going to the second boxes leave the upper part of the main staircase at that point. This lessens comfort and the sense of parade for those using the second boxes. Since when one constructs a building all aspects must be considered, even the prejudices of the public, this hindrance has to be acknowledged. Furthermore, when arrival occurs above the ground floor vestibule, it suppresses the grand order of the stair cage as with the previous parti, again producing two distinct cages, which is always a bit mean in comparison with a single grand vessel.

One can partly remedy this fault by arranging the arrival of the two upper flights not on a whole floor over the vestibule, but at a landing of the same width as the staircase. In this way, apart from the landing the vessel is open. The two flights lengthen, approach and join, but always within a single space. This arrangement seems convenient if one does not reproach the landing for cutting the architectural order where it is added, and obscuring the wall of the end of the cage from the spectators who arrive and begin to mount the stairs. But the addition of stairs and landing is a real obstacle to free lines of sight, and no matter how cleverly the motif is studied, there is no avoiding that disagreeable addition. I do not claim this fault is reason enough to reject the whole parti, for there are so many ways of composing an artistic arrangement that I cannot deny that the disadvantage might be overcome. I wished only to describe the motif, its qualities, and the aspect that presents most difficulties for its artistic arrangement.

There remains one more parti, and as it is the one I believed necessary to adopt, it goes without saying that its qualities seemed to me to outweigh its faults. This motif is certainly not new. Examples can be found as far back as the Italian Renaissance, and it has sometimes been deployed in buildings over the last two centuries. It made its reputation with the Grand Theatre of Bordeaux, where that great architect [Victor] Louis gave it a special place. Since then it has remained as a type more or less modified, but which retained the great advantage of being simple and logical. In adopting it for the new Opéra, I hope at least to have given it a more particular character, which I have designed with more suppleness; but its basic parti derives from that first arrangement, which seemed to me to conform most to the exigencies of art and reason. I have had no reason to hide its fortunate parentage, and I am more at my ease in making this observation since, whatever parti I had adopted, it would always have been used earlier in some form or other. Types are limited: one cannot help but ascend at the front, at the back, to right or to left, and it is above all in the development of a motif that diversity and originality make themselves felt.

Let us now examine this motif and understand the reasons that militate in its favour. The arrangement is simple: on the building’s axis the arriving visitor encounters a great monumental flight of stairs. It rises to a landing in front of a first entrance, then the route divides, one flight rising to the right and the other to the left, both ending in galleries at the level of the first boxes. The form is almost naïve, but despite its simplicity it adapts itself to all requirements. At the top of the first flight a central doorway leads to the baignoires and the stalls of the amphitheatre, and that accomplished, the lateral flights lead on up to the first boxes. Now as the two opposed flights and the landing between them only take about 20 metres, one arrives close to the median part of the corridors for the boxes. Before people reach the end of the two upper flights, the secondary stairs are visible directly opposite. Audience members stopping at the first boxes turn right or left according to the direction they have chosen to climb, while those progressing to the second level of boxes continue straight on. There is again division of the crowd, generous facility of communication, and logical arrival at all seats. These conditions fulfilled, let us see if others are too, and if the communication of the boxes with the foyers is broad and easy. Since the width of the cage scarcely exceeds 20 metres, the galleries of the passage established to each side will align with the middle of the corridors of the hall, to give the greatest average proximity to the seats and proximity to the foyers, all with direct view of the route. There is no embarrassment, no detours to get from hall to foyers, so again the problem seems resolved.

We saw earlier that, when two opposed flights were reunited by a central landing, it masked part of the wall. In this case, on the contrary, the two opposed ramps instead of being reunited, extend one another, and the upper landing is removed. As for the intermediate landing, the blocking of the lower wall, being at a far lower level than the landing of the earlier case, and diminishing almost geometrically with height, leaves the door at the bottom almost completely visible, and the lateral flights sloping up to the floor of the boxes do not hide this arrival at all. The walls of the cage are therefore exposed, it is vast and unencumbered, and if the architect decorates it with talent, the motif seems to offer all necessary resources.

I sought the inconveniences that could arise from this arrangement, and can honestly say I have only found just one. It is that the landing by the doorway to the baignoires, being unable to exceed the width of the steps, is relatively restricted in size, and does not permit more than a single opening on the axis of the main flight. It is large enough for arrival, but one might fear when everybody leaves that it will be a little crowded, made worse by the way people leaving through that opening will collide with those descending from the first level of boxes. This would produce great inconvenience if the principal stair was not complemented by secondary stairs, which well connected, will invite use by audience members coming from the lateral corridors. Only the central crowd will take the main staircase, and since the corridors, like the special doors giving access to the median levels, can be well placed to right and left, one can believe that the middle door will suffice for practical purposes of exit . . .

Finally, if the grand central stair is a sumptuous and eventful place, if the decorative treatment is elegant, if the animation which dominates the stairs is an interesting and varied spectacle, there will be advantages from which all can profit. If one then places the lateral walls of the stair cage in such a way that they are always open, all persons circulating on every floor can if they wish find interest in the view of the grand stair and the incessant circulation of the crowd. It will be good then to make the vertical walls very largely open to the cage, and to create openings to the large balconies that allow a good position and easy view of all movements taking place on the grand stair. This is rational, practical, artistic, and leads inevitably to a motif that is rich, grandiose and eventful. On each floor the spectators leaning on the balconies decorate the walls and seemingly bring them to life, while others ascend or descend, adding further life. Finally with the addition of cloth and flowing draperies, with many-branched chandeliers, lustrous surfaces, marbles and flowers, colour throughout, one makes of the whole a brilliant and sumptuous composition reminiscent of canvases by Veronese. The light that sparkles, the resplendent costumes, the animated and smiling figures, the meetings and greetings: all give an atmosphere of feasting and pleasure, and without being conscious of the part played by the architecture in this magic effect, all enjoy themselves, in their happiness paying homage to this great art, so powerful in its manifestations, so elevated in its results.

Notes

1 Charles Garnier 1871, Ch. 4, pp. 57–94.

2 Robin Middleton in Middleton and Watkin 1980, p. 244.

3 Literally bathtubs, a particular layer of large, open boxes at the back of the stalls.