Childhood and Education 1907–1927

I was always interested in education. I think it was the education stuff from my father that came through.1

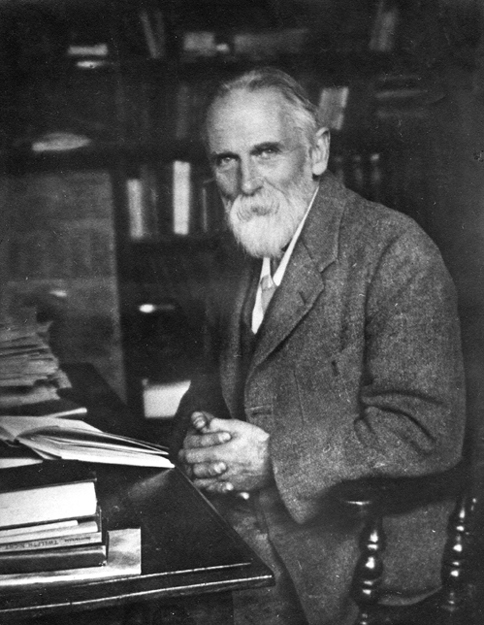

Mary Beaumont2 Crowley was born in Bradford on 4 August 1907. Her family was a very important influence on her life and chosen career and, in particular, her father played a large part in the decisions she took about the way her personal and professional life would develop. Ralph Henry Crowley (1869–1953) (Fig. 1.2) was a Quaker by faith and a medical officer by profession and his combined social conscience and confidence in the means by which society could and should be changed for the better shaped his life and promoted his keen interest in the education and the welfare of children.3 He had graduated in medicine in 1893 and as a young man went to Bradford to work for the pioneering Bradford School Board as Medical Superintendent of Schools.4 This was a time of high infant mortality when municipal authorities in the northern industrial towns such as Bradford were beginning to introduce preventative measures to ward off the spread of infectious diseases and improve the health of the population. Increased awareness of the impact of poor living conditions on general health was leading medical experts such as Crowley to realize among other things the vital importance of ventilation in buildings supporting large numbers of children. This awareness was part of a Europe-wide open-air school movement that introduced some experimental designs of schools built with flexible walls to open easily to the outside with implications for the way that the whole school was designed.5

In Bradford, Crowley met Muriel Priestman, also from a Quaker family of wool merchants and they married. The Priestman family were involved with educational movements locally and had been founders of Friends schools in Bradford. There was also a connection between the Priestman and the Clegg families that would prove to be significant later in Mary’s life.6

Mary resembled her father physically and was thought by those who knew them both to be very like him in character. They shared a tendency to act without regard for personal gain or public recognition. She was also drawn to people who were similar to her father in character and personality and through his many contacts in architecture and education, came to know some of the most significant progressive educational thinkers and practitioners at home and abroad. Many of Mary’s closest acquaintances and most admired individuals were Quakers too.

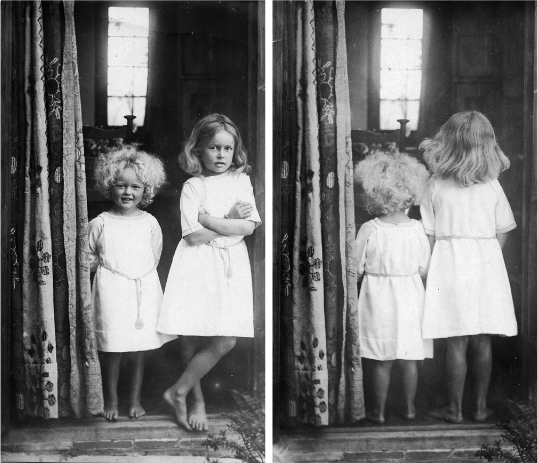

1.1 An intimate portrait of Mary and her mother Muriel in their Letchworth home. c. 1910. This is quite an informal and intimate photo for 1910, representative of middle class progressive adult child relationships. IOE Archives, ME/A/1/9

Ralph Crowley devoted his career to furthering the understanding of child welfare, and developed a profound interest, before the First World War, in the organization of innovative educational environments in support of ‘the whole child’, a phrase he is credited to have originated. He argued that such a concept posed profound challenges for professionals involved with the care or development of children in the future.

1.2 Ralph Henry Crowley. IOE Archives, ME/A/1/4

Our study, consequently, must be directed, not to this or that defect, or disease or symptom, but to the whole child – to the body and its physiological working and pathological changes; to the mind, as manifested by the general and specific intelligence and the general and specific behaviour of the child; to the environment at home and at school; to the child’s heredity.7

To these ends he travelled widely seeking out the most child-centered and efficient environments from the point of view of the health and well being of the individual. He was interested not only in function but also in the character of any planned educational environment

In the planning of the school the aesthetic side should not be forgotten. The keynote should be everywhere simplicity; perfect beauty and perfect hygiene are quite compatible. The school architect should be, of course, as should all architects, an artist: that does not mean that the construction of the school will cost more; a beautiful school, simply built may cost less than an ugly and ornate one.

He considered that even the colour of walls came within his remit of caring for the whole child, ‘… the walls should be tinted, preferably a soft grey-green in the more sunny classrooms, and an ochre tint may be used in the less sunny rooms … and yellow and red tints should be avoided in rooms naturally bright’.8

As we shall see, these remarks by Mary’s father, and published when she was a small child, resonate strongly with the features and characteristics of the approach she took to school design in later years working as an architect, first for Hertfordshire County Council and later for the Ministry of Education (from 1964, Department of Education and Science).

Ralph Crowley was a key figure in an international movement to establish school hygiene and a compulsory medical inspection service in elementary schools and he pioneered the introduction of open air schools in England.9 By 1912 there were open air schools in several counties in England, the best examples being in London, Birmingham and Bradford.10

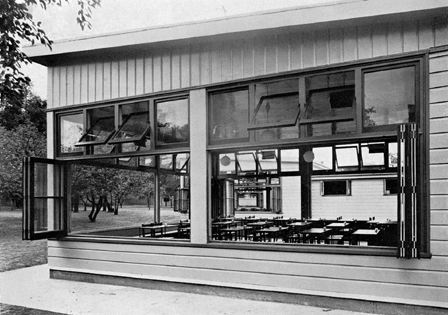

Mary Crowley once noted the close resemblance between the timber pavilions at the Busch House Open Air School for Delicate Children, Isleworth (Fig. 1.3) that her father officially opened in September 1938 and her own planning of Burleigh Primary School, Cheshunt shortly after the war. Others have noted the influence of the English open air schools on the architecture of Crow Island School, Winnetka.11 There are certainly important connections between the design of open air schools in the first quarter of the twentieth century and post-war designs that achieved a similar feeling of openness to the elements through extensive fenestration, especially in glazed unit corners.

But apart from his enthusiastic engagement with his work, Ralph Crowley was also ‘a man with infectious enthusiasms – his knowledge of flowers, shrubs and trees and vegetables too, was encyclopedic’.12 Mary inherited her father’s interest in and knowledge of botany and later declared it one of her guiding principles to preserve and plant trees when building schools. Her father’s enthusiasms were ‘boyish in their intensity and … (he) always appeared to be much younger than his real age.’13

In Bradford, as school medical officer, Ralph Crowley had initiated an experiment in feeding school children alongside the campaigner and educator Margaret McMillan.14 In 1908, shortly after the Liberal Government reforms of 1906/7 had laid the basis of child welfare service through schools, Crowley was recruited to the Board of Education in London. There he became Senior Medical Officer in charge of medical staff but once again, he attempted to broaden the remit. His concern was not merely with medical problems; he was as interested in the educational as in the physical development of the child.

1.3 Busch House pavilion, 1938. IOE Archives, ME/A7/4

1.4 Crow Island School, Winnetka, USA, 1941. Copyright Cranbrook Archives, Richard G. Askew, photographer, 5676-3

Taking up the new post in London necessitated moving the family south and the Crowleys took their young family to live at Letchworth in Hertfordshire, an experimental new town with many like-minded enthusiasts who imagined and were committed to building a better world through community and cooperation. It was at Letchworth, the world’s first Garden City and an experiment in planning instigated by Ebenezer Howard, that the Quaker architect Barry Parker15 designed a family house for the Crowleys – the last house at the end of Sollershot Road – overlooking a farmed landscape in the direction of Hitchin.

The Garden City was ‘a town designed for healthy living and industry of a size that makes possible a full measure of social life but not larger, surrounded by a rural belt: the whole of the land being in public ownership, or held in trust for the community’.16 Many Quaker families, like the Crowleys, were involved in the Garden City movement at this time including some of their friends and relations. These included the Cadbury Brothers, also Quakers, who commissioned an ideal village for their chocolate business workers, and others, called Bournville, near Birmingham. Sir Ebenezer Howard’s book Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, published in 1898, inspired many of these individuals who collectively introduced the Garden Cities of the early twentieth century.

The comfortable household of the Crowleys consisted of the parents and a Mrs Hargreaves brought with them from Bradford as a ‘lady help’ for their two young daughters. Mary’s mother created a pleasing environment and bought good pictures and fabrics from artists and manufacturers associated with the Arts and Crafts movement to decorate the home.17 The staircase with its rope handrail was at first open to the sitting / dining room but this was subsequently closed off on account of rude remarks that might be made about the many visitors from the two daughters sitting on the stairs.18

Mary’s early years seem to have been rather idyllic when she was able to play freely and wildly in the adjacent fields and about the house. She recalled climbing the roof tiles to sit on the ridge and that this caused little alarm about safety. Later, she learned to ride a horse, one of her passions enjoyed formally and informally. A farm worker in nearby fields allowed her to accompany him at his tasks. ‘I sat on his horse when he ploughed … and … drove his wagon back to the farm … like an ancient warrior, standing up and holding the reins taut, both the horses and I wanted to gallop.’19

At night she was afraid of the dark but was calmed by the sound of her mother’s piano, from which she acquired her lifelong love of music. Her vivid memories of these early years include learning piano, starting with the black notes, and acting in a play, taking the part of a piece of ivy. The local community, in the early days at Letchworth, was artistic and eccentric. Neighbours included the Olivier family where a young Laurence, later to become the world-famous Shakespearian actor, lived. There was also a Miss Birch who painted a portrait of the very young Mary, clutching a rag dog. It was from this artist, in her home, that Mary took her first drawing lessons. From about the age of ten, Mary began to keep a diary and we have her nature diary as a record of her early drawing.

1.5 and 1.6 Mary and her older sister Elfreda at their home in Letchworth, c. 1910. IOE Archives, ME/A/9, IOE Archives, ME/A/1/9

The house in Letchworth hosted regular and frequent meetings where enthusiasts for the Garden Cities developed their ideas for planning a new town. This was to become Welwyn Garden City, designed by the young French Canadian architect Louis de Soissons in 1920 where the Crowleys were to take up residence soon after its development. By this time, Mary was boarding at school but her new home at first was the upper storey of an old farmhouse with barns, a pond and a silo. Here, her parents took responsibility as wardens of a hostel catering for Garden City workers between 1921 and 1925. Thereafter, the Crowleys moved once again to a family house in Bridge Road, Welwyn Garden City.

During her childhood, Mary would have become used to her father’s regular trips abroad and on his return would have taken part in conversations about educational environments he had encountered. In this sense she was ‘born’ into education and for Mary, the subject was part of everyday family life. There were important connections established with the progressive educational movement in the USA at this time that would eventually bring to Mary’s attention some of the possibilities of reforming schooling through the uniting of education with architecture. In 1913, as a delegate of the Board of Education, Crowley attended the fourth International Conference on School Hygiene at Buffalo, USA. While on this trip, he took the opportunity to visit several American and Canadian cities to examine progress in medical service provision for schools. In Toronto, he discovered an open air Recovery School established in 1912 on Lake Ontario for 100 children, which would have encouraged his interest in open air school plans, discussed in his book.

He visited schools for ‘the feeble minded’ in New Jersey, and Epileptic Colonies in New York. But he also became particularly interested in the playgrounds movement that he discovered to be flourishing at this time in some of the major cities on the east coast. On children’s playgrounds, he commented.

there is nothing corresponding in this country to this playground movement in America, although it has been steadily developing there during the past 20 years – (where) the school itself becomes the social centre with extensive playgrounds attached, the highest development of this kind is to be found in Gary (Indiana) … the playgrounds form part of the school ‘plant’. They are available also for adults … and are in continuous use from 7.45 am onwards … open all the year round.20

The playground movement was also flourishing on the west coast where it provided employment for progressive educationalists including a young Carlton Washburne (1889–1968) who was later to establish a progressive agenda in public schools in Winnetka. Also in the mid-west, at Gary, Indiana, Crowley witnessed the practical realization of new ideas about the arrangement of school sites and buildings to support children’s well-being in line with a pedagogy of self-directed learning.21 Shortly before his arrival there, the progressive educator, William Albert Wirt (1874–1978) had become district supervisor in this new multiethnic community built around the burgeoning steel industry.22 Here, Crowley had the opportunity to visit the buildings that gave expression to Wirt’s educational philosophy. He noted the arrangement of buildings housing different sized units for different purposes and the importance given to the outside environment which was conceived as another ‘room’ available to children. In these schools, there were to be found only a limited number of rooms fitted with ordinary desks and seats and particular importance was given to enabling children to learn practical life skills. He reported that ‘part of the ground is used for school gardens, trees are planted wherever possible, and there are several animal houses constructed by the pupils’.23

Wirt had introduced a system known variously as the ‘Gary’, ‘Platoon’ or ‘Work-Study-Play’ plan for elementary grades. Pupils were divided into pairs of units of equal numbers and while one unit was occupying study rooms, the corresponding other would occupy the general work / play areas thus maximizing the use of facilities at all times. The schools were open to the community in the evenings, weekends and summers and the curriculum was expanded to include manual training, recreation, nature study and other non-traditional subjects.24 All parts of the buildings were engaged in instruction through careful design. Corridors, so often vacant and institutional and serving the purposes of circulation only, in the traditionally designed school, were here put to educational use.

The idea of using every part of the school plant as an educational opportunity has been worked out with great success and considerable economy. The upper corridors of the school, for instance, are beautifully lighted and are used as museums and picture gallery.25

It was such modern schools without classrooms where it was intended that children should be motivated by the freedom allowed them to work at their own pace and at their own preferred subjects and where they could see the immediate usefulness of the work they accomplished that Crowley chose to highlight on his return in reporting to the Board of Education. Such schools in certain districts led by progressive educators were influenced at the time by the philosophy and practice advocated by John Dewey (1859–1952) with reference to the importance for children’s learning of first hand experience, and Frederik Lister Burk (1862–1924) with regard to systems supporting self education. The work of progressive teachers in the USA demonstrated how ‘real education’ – which Crowley understood as synonymous with ‘progressive education’ – could become accessible not only by the relatively rich, as was the case in England and the USA, but through public education by ordinary working people.26 This was the social justice at the heart of Crowley’s interest in and understanding of educational well-being. This trip was to have significance later for Mary, in her studies at the Architectural Association, when in 1932 she referred directly to the Gary public schools as an inspiration for her fifth year prize-winning thesis which was a plan for an education and welfare centre.27 Later still, the educational and architectural project of changing classroom design to reflect advances in pedagogy was an aspiration she held with others over many decades.

Ralph Crowley’s interest and involvement with the United States continued for some time and in the 1920s he once again sought inspiration there for his work developing Child Guidance Services, noting the importance of relating the two areas of education and medicine in the interests of ‘the whole child’.28 A few years later, as Mary Crowley was beginning her working life, exhibiting an enthusiasm for the experimental village colleges pioneered by Henry Morris in Cambridgeshire, in an address to the Friends Guild of Teachers, he put the timely question, ‘Is it too visionary to see in the school the centre of the educational and recreational life not only of children but also, transcending its present boundaries set by age and type of work, of the community it serves?’29

Ralph Crowley’s interest in progressive education, and the environments that such an education required to support that ideal, lasted throughout his life and formed the basis of a strong bond with his daughter who, he ensured, was receiving at first hand the experience of a progressive education and developing her artistic talents alongside a commitment to social justice inherited through her Quaker family. It was probably Ralph who introduced his daughter to the work of Carlton Washburne who in 1919 was appointed superintendent of Winnetka’s public schools and inspired by the nearby achievements at Gary, as well as by Dewey’s Laboratory schools at Chicago, was then embarking on his own path of school reform destined to last throughout his career.

Admiration for her father’s various passions and his work for the public good clearly influenced Mary even as far as her eventual choice of profession. Initially, she had wanted to pursue her first love, drawing, but it was Ralph who persuaded her to train to become an architect.

I decided to be an architect when I was about 15 or 16 – just walking down one road, I remember, with my papa and we were talking about things and I think the idea came up and I said what about architecture and he sort of agreed, but nothing more was done about it at the time.30

EDUCATION AND SCHOOLING

It came through drawing.31

We had a nursery room– with a long low chalk board along the wall – I could sit on the floor and draw.32

The end of the nineteenth century saw the establishment in England of a number of independent schools that were set up on lines that offered an alternative to traditional curricular and pedagogies.33 These appealed to non-conformist families who wished to provide an education for their children that would prepare them for an active life of service in the cause of social justice. Typically, they emphasized the arts – especially the practical arts. Many individuals who trained in architecture during the inter-war period belonged to such families and experienced such an education. This was particularly important for women as the independent sector provided the first co-educational secondary schools.34 Some, such as Jessica Albery ‘had no formal education until 5 years at the Architectural Association School’.35 Mary was of a generation and social class for whom education at home might have been the norm but because her parents were significantly interested in progressive schooling, she experienced a number of experimental schools before adolescence. As a young child, she was educated partly at home and partly in a variety of independent day schools. First, she spent some time at St Christopher’s School, near the Cloisters, at Letchworth.

St Christopher’s was a progressive school embedded in the Theosophical movement with a number of exceptional characteristics for its time. No uniform was required, children received a vegetarian diet and there was a strong ethos of democratic accountability and responsibility as well as an anti-authoritarian atmosphere where teachers and pupils addressed one another by first names. The Theosophist and co-founder of the New Education Fellowship (NEF), Beatrice Ensor, head teacher at St Christophers between 1918 and 1925, would have been known to the Crowley family and was most likely one of the more frequent guests at their home.36 The school was found to be satisfactory in most respects but the strict vegetarianism worried Mary’s parents as she was of slight build and it was thought best to move her to another progressive school nearby.

This next establishment was a small school in a domestic house in Norton Way South at Letchworth which was run by a Miss Cartwright and a Miss Paget-Kemp. Here, there was also an atmosphere of freedom, so much so that a campaign was drawn up among the pupils to request that they correct their own sums which Mary supported and was excited enough to write about in her diary. Her diary also records numerous occasions when she was put to gardening rather than sums owing to problems with her eyes and the delay in getting the correct spectacles. From such activity and from her father, she learned the names of trees and plants and developed a belief in the importance of their integration into the life of individuals and communities. At this school she also learned some housewifery alongside the nature study and gardening and recalled having ‘ripping fun’ in the sandpit. The music lessons, however, were not satisfactory to Mary or her parents and so a private tutor was arranged to visit the home, which resulted in Mary becoming a fine pianist and playing for the rest of her life. A very different educational plan had been put in place for Mary’s elder sister Elfreda, who as a boarder at the Quaker all-girls Mount School37 in York was occasionally homesick.

1.7 Mary at home in Letchworth with the family pet dog. IOE Archives, ME/A/1/9

For one term only, at the age of 13, Mary attended an experimental school managed by Isabel Fry (1869–1958), sister of the art critic Roger Fry and daughter of Sir Edward Fry, a famous Quaker Jurist.38 This was The Farmhouse School, at Mayerstone Manor, an eighteenth-century domestic house and stables set in 35 acres of pasture and woodland, situated between Great Missenden and Wendover in Buckinghamshire. ‘The earlier part of the house was in William and Mary style, square and low with square sash windows. The two front rooms were the library, filled with books and periodicals of all sorts for everyone to read, and the senior classroom.’39 Although this was a brief experience, the school environment and Isabel Fry’s philosophy was marked and Mary experienced an unusual sort of education characterized by small group work, a domestic environment, visual methods of teaching and ‘learning by doing’.40 The Farmhouse School had started in difficult circumstances due to war time shortages and anxieties in January 1917. Isabel was 48 years old when she opened the school, had never trained as a teacher and had few qualifications. But accounts tell that ‘she had an excitement about the physical world, an enthusiasm and wonder that informed her teaching and infected her students’.41

There was also her unlimited vision and interest, which comprehended the physical, the cultural and the spiritual. In her teaching there was no insulation of one from another: gravity and delight, aesthetic quality and function, action and peace, the transcendent and the factual, might jostle each other at any moment. But there was never confusion: the specific object to be achieved, at that moment, was always clear.42

In her classroom teaching, there was a strong emphasis on the senses and, ‘feeling, hearing, touching and seeing played their part whenever possible in her lessons’.43 Another pupil from the time recalled, ‘her skill in making, and causing us to make, models and diagrams of all kinds, was something that especially appealed to very small children … (and) she made us draw (maps) and on to which we stuck tiny models or sketches of our own showing the products or features of each region’.44

Isabel believed, like many other progressive educationalists at the time in the importance for children of appreciating and nurturing living things and The Farmhouse School kept farm and domestic animals and was almost self-sufficient in food, not a small thing in the war years and immediate aftermath. Mary, who recalled being somewhat ‘in awe’ of Isabel, remembered being sent to care for ‘inanimate things alone with the gardener’ and an episode with some lost rabbits. She was in an environment where ‘teaching was an act of creation everyday. And it was not, (for Isabel), a theory but a practice.’ 45 Among Mary’s fellow pupils was the artist, Julian Trevelyan (1910–1988), who went on, like Mary, to be educated at Bedales. Trevelyan, a printmaker and painter in adult life, became interested too in education and produced a lithograph for the School Prints series and at least one mural for a Hertfordshire primary school during the early 1950s.46 Mary ‘enjoyed Isabel’s talks and readings in one of the living rooms, and playing the piano in another’ but in general found the place too ‘claustrophobic’.47 This is a pertinent criticism given her later interest in providing school buildings that were characterized by a welcoming openness, space and light.

It was no doubt the connection with Quakerism that had encouraged her parents to send her to Mayerstone Manor. The characteristics of this school were essential to progressive schooling as it was understood at the time in the independent sector and were already being proposed as necessary features of mass education by advocates of ‘new education’. These same characteristics would form foundational elements of Mary’s philosophy of design when she planned school buildings at Hertfordshire County Council and later for the Ministry of Education (DES).

Isabel Fry was associated with a progressive movement of teachers, academics and advisers who were at the time influenced by the theories and practices of John Dewey in the United States and Maria Montessori in Europe. Their efforts to form a collective to promote progressive ideas and practices resulted in a series of conferences that led to the establishment of the New Ideals in Education conference, a forerunner of the New Educational Fellowship.48 Therefore before moving on to consider Bedales, the school that Mary had the most affection for, we can summarize that Mary Crowley’s first experience of education exposed her to progressive educational ideas and practices as well as to the domesticity of a dwelling that had not been intended as a school in its initial design.

Bedales

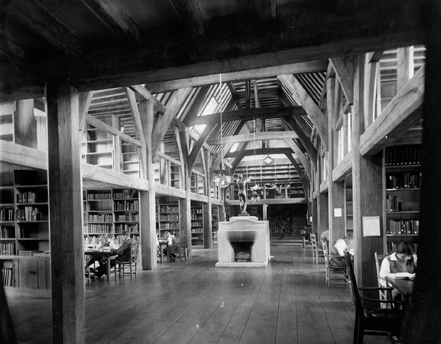

From 1921 until 1926, Mary attended Bedales School, a co-educational establishment founded John Haden Badley (1865–1967) in 1893 (Fig. 1.11). Here, she recalled feeling that she was in the right place among like minded spirits and, although shy and studious, formed important and long lasting relationships with other pupils and staff. Architecturally, the school was boldly styled in the Arts and Crafts tradition and so was a stimulating environment in which to learn for a natural artist and future architect. Andrew Saint notes that Bedales was of exceptional architectural merit among the progressive schools of the period. The Memorial Library designed by Ernest Gimson, built by Geoffrey Lupton and overseen by Sidney Barnsley was completed just as Mary arrived in 1921. The library was an inspiration to her and a regular haunt as she pursued her passion for drawing. As she later explained, ‘you were always allowed to go and work in the evenings in the library, and you often had things to do there’.49

1.8 Bedales school, Petersfield. IOE Archives, ME/A/2/2

1.9 Interior of Bedales Memorial Library, designed by Ernest Gimson. IOE Archives, ME/A/2/2

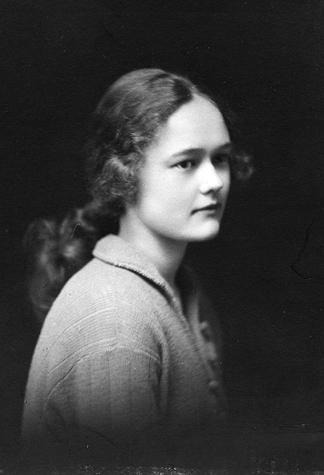

1.10 Portrait photograph of Mary at 14 years. IOE Archives, ME/A/1/11.

School reports record that she showed originality and imagination. Later reports indicated a tendency to take her work too seriously and become over anxious about her ability, a trait which lasted into early adulthood as her diary entries testify.50 This experience of education certainly laid the basis for the rest of her professional and personal life, enabling her to flourish and find expression for her talents in drawing, music and art.

John Haden Badley had founded Bedales as an alternative model to the established English Public Schools, and Badley (known affectionately by his pupils as ‘the chief’) was headmaster during the years that Mary attended.51 While an undergraduate at Cambridge, Badley had been inspired by the writing and political philosophy of the social reformer Edward Carpenter and the poetry of Walt Whitman.52 Having experienced a traditional education himself first at Rugby School and then at Cambridge University, Badley was convinced that such formal classical schooling was no longer appropriate or of relevance in the modern world. He sought to create an alternative that would link liberal studies to practical application. Towards this ideal in 1889, he joined with others of similar intent, including Carpenter and Cecil Reddie, in launching an experimental school at Abbotsholme in Derbyshire. Political disagreements with the founders led to Badley seeking to start a school of his own, and, finding land near Petersfield he opened Bedales, the school that was to provide for Mary Crowley an educational model that influenced her choice of career and reinforced her lifelong engagement with education.

1.11 John Haden Badley of Bedales. IOE Archives, ME/A/2/2

At Bedales, there was a fundamental emphasis on the arts and crafts and some outdoor and farm work was encouraged. In this sense, Bedales provided continuity with Mary’s earlier experiences of schooling. She noted in her diary that when she first arrived at Bedales she felt immediately ‘at home’ with the teaching staff including Badley, Osbert Pearl (deputy headmaster) and Laurin Zilliacus (Science master) (1895–1959). Zilliacus was a charismatic Finn who was soon to take a leading role in the New Education Fellowship and who later formed a strong friendship and emotional bond with Mary. Zilliacus had originally attended Bedales as a pupil and developed a life long interest in the study and propagation of progressive education, establishing a school himself at Heligsford in Helsinki. As we shall see, Zilliacus played a significant part in Mary’s life until the outbreak of the Second World War.53

A key aspect of the bold experiments in progressive education at the turn of the century was the aim to unite vocational and practical learning with cultural understanding and liberal education. The classical curricula of the older Public Schools had been experienced by the founders of new and reforming establishments, who had felt themselves as a result ill prepared to meet the challenges of a world where old certainties of national and personal identities were shaken. For Badley, education was three-fold. First there was instruction, secondly training whereby the learner ‘should not merely accept knowledge at second-hand, but should do for himself the thing in which the attainment of skill is required’, later referred to by Mary as ‘first hand experience’ and third, ‘more important’ was environment. ‘It is in the importance that the “new schools” attached to environment, in their insistence on healthy surroundings and conditions of life, on the provision of opportunities for a wide range of interests, and on comradeship and co-operative activity in self-government rather than on reliance upon authority and regimentation, that their most characteristic features are to be found.’54 These very principles were reflected in Mary Crowley’s later designs for schools to serve the general population as progressive practices came to be more generally accepted through state schooling.

Bedales experimented with pedagogical models drawn from contemporary progressive educationalists in the USA and in Europe. The Montessori method was of interest to Badley and we know from his memoirs that Maria Montessori visited in the early days, as did Helen Parkhurst from Massachusetts who discussed her own approach known as the Dalton Plan after the High School where it was practiced. This method, the origins of which were developed in the USA by Frederic Lister Burk, influenced a number of educational reformers during the 1920s and was at root accepting of individual differences in learning. With a foundational common assignment to be completed within a given time, it was believed that pupils should be allowed to progress at their own pace and to learn, as far as possible, in their own way. Classrooms became known as a ‘laboratories’ or ‘workshops’ ideally no longer dominated by the voices and personalities of teachers but places where the pupil worked on a particular task while the teacher remained on hand to provide help. A variant of this system was adopted at Bedales but by the time Mary joined the school community it had become somewhat modified to include some general instruction.

Bedales provided opportunities for pupils to develop not only their academic skills but their personal interests as well as self motivation, self discipline and the persistence needed to solve a problem or complete a task. As the architect Henry Swain (1924–2002) with characteristic enthusiasm later remarked, the Dalton Plan, which he had experienced at Bryanston School, proved to be an excellent introduction to architectural training. ‘It was an adventure … where you didn’t go to classes all the time, you worked on assignments, like the AA [Architectural Association], like life, with a time limit and reference books and people to talk to and great spaces to work in.’55

Among the many visitors to Bedales during the early years was the newly appointed Superintendent of schools in Winnetka, Carlton Washburne. Washburne would later directly influence Mary’s philosophy of education through his publications and the construction of an elementary school building that vividly expressed and supported his clearly articulated views on teaching and learning.56

Directed by the recently formed NEF to some of the most interesting new establishments in Europe, Washburne took a four month tour of European experimental schools in 1922–1923. Bedales was already a well known example and in his report to the Federal Bureau of Education, ‘New Schools in the Old World’, Washburne stated he regarded Bedales as ‘perhaps the most progressive and alive of all the “New Schools”’ and among ‘the finest schools found in Europe’.57 Some years later, Washburne explained what he meant by progressive education, using language familiar in the Crowley household. ‘Its two basic tenets are the education of the whole child and education for the democratic way of life.’58 Other visitors to Bedales came from Europe but also from further afield including the Indian educational philosopher, teacher and poet Rabindranath Tagore, founder of the community of Santinikatan.59 Tagore was also closely acquainted with Leonard Elmhurst, founder of Dartington Hall who in the 1960s was to become a friend of Mary Crowley and David Medd.60

Contemporaries or near contemporaries of Mary at Bedales reflect the degree to which the school was used by what could be described as a cultural elite of the time. They included Denis Clarke-Hall, who later, like Mary, went on to study architecture at the AA and became an influential schools architect, and Julian Fry, son of the art critic Roger Fry who himself had been a friend of Badley’s at Cambridge and who went on to support the school. Other pupils included the sons of Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald, a ward of George Bernard Shaw, and the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead’s son and grandson. Mary stayed an extra year at Bedales, spending most of her time doing measured drawings of Petersfield church, and was head girl for both of her final two years.

Mary kept a diary, recording day to day events at Bedales, and in this we see the development of her interests and formation of strong and lasting friendships. In these records she often mentioned food and dinner menus, usually with disappointment, sometimes describing meals as less than appetizing vegetarian ‘mush’. Other experiences were not dissimilar to any girl of her age, and social class, walking up to the ‘chalk pit’ with friends to ‘fool around’, life in the dorm, welcome letters from home, occasional illnesses and deep longings for family and home. On Sundays she and her fellow pupils were regularly summoned for an informal ‘talk’ with Badley and other routine events were noted such as ‘inspection’ (boot and shoe, macs, coat and hat) and ‘whole school dancing’ in the quad.

1.12 Mary Crowley, Laurin Zilliacus and unidentified man. IOE Archives, ME/A/2/2

According to her diary, the summer term of 1924 became something of a turning point. Mary was 17 years old and a remark suggests a significant change in her feelings about herself in relation to others at Bedales, particularly towards some for whom she was developing stronger and more mature feelings. ‘It was then I think that I ‘grew’ into the older set, in a way; it seems that was the beginning of a different stage.’

Possibly reflecting with a certain self consciousness on her growing affection for Laurin Zilliacus and a change in the nature of her feelings, she commented, ‘I was an idiot about one thing that term. It seems funny now, but it wasn’t then. That was the term, too, when I got to know Zil more.’61

Expeditions to nearby places were made with Zilliacus and others and Mary enjoyed her first experience of driving in ‘Zil’s’ motor car. Finally, she remarked on the ‘rather tense end of term’ because so many people who had become important to her were leaving. These included even her cherished teacher, Zilliacus, who was embarking on a tour of progressive schools in the United States. From this time a regular and increasingly intense correspondence between the two of them ensues until the outbreak of the Second World War.62 Mary was to return many times to Bedales to meet with staff and alumni over the following years.

After leaving Bedales, Mary’s parents advised her to spend some time abroad, not as a formal ‘finishing’ but for the experience and to become a better linguist. She agreed, and left England in the autumn of 1926 to stay for six months in Switzerland, near Lake Geneva at Lausanne, attending a language course at the University. The intention was that she learn French but she was not particularly talented at language learning and spent a lot of time pursuing her main interest and passion for drawing, ‘large and bold with black chalk and pencil’.63 She had already decided to train as an architect but this impulse came through drawing.

A young woman, newly out of school, Mary naturally sometimes reflected on fundamental questions of life, beauty and faith during these years. The great loyalty and affection for her parents, especially her father, may have prevented a complete break with her Quaker faith but doubts began to surface and continued, coming to a head during the war years. Somewhat reluctant to let go of the certainties of her youth, shortly before commencing her first term at the AA, Mary returned to Bedales for an Old Bedalians meeting. The return reinforced her sense of belonging among like-minded spirits.

When I go back to Bedales I meet my friends, people who’ve been used to looking at things often from the same point of view and have the same interests and difficulties … Bedales is good because it is understanding and you can unbottle yourself.64

But she knew that however comfortable and at home she felt at Bedales, it was time to let go and reluctantly but inevitably move on,

… in the interval we get rather between two stools neither with established interests outside, nor with Bedales wholly to fall back on. Its then that we’re rather forced back on ourselves and one or two friends, with so much to ask and so little we can find answers – we are left to choose and find out for ourselves, and all the time the time is going and we cannot get beyond the questions.65

Many questions loomed in Mary’s mind at the time but the principal one was how she might come to know the road in life that would put her talents to serve in the interests of humanity. It is also clear from her correspondence and diary entries that Mary was coming to terms with her deepening affection for Laurin Zilliacus. Zilliacus was several years older than Mary and was married with two small children. Nevertheless, he allowed his own affection for ‘Maria’ (as he liked to call her) to grow. Bedales was a convenient place at which the two could meet, talk and realize more fully their mutual attraction in the guise of a neutral rendezvous.

NOTES

1 Architects Lives. National Life Stories in partnership with the British Library – Mary Medd interview with Louise Brodie, August, 1998. The interview is split into 6 tapes. Transcript ME/B/3.British Library List Recordings C467/29/01-06.

2 Beaumont came from the name of a great grandmother.

3 Ralph Henry Crowley had been educated at Brighton Grammar School and at Oliver’s Mount School, Scarborough. Obituary notice, British Medical Journal, 10 October 1953. p. 833.

4 Bradford became a Local Educational Authority in 1902.

5 For the open air school movement, see A. Châtelet, D. Lerch and J. Luc (eds) (2003) L’École de plein air: Une expérience pédagogique et architecturale dans l’Europe du XXe siècle [Open-Air Schools. An Educational and Architectural Venture in Twentieth-Century Europe]. Paris. Éditions Recherches.

6 DLM mentions this relationship in a letter to the author, 12 February 2008.

7 Ralph Henry Crowley, ‘The Mental Health of the Child’. Paper for the Federation of Education Committees conference, 2 June 1933. p. 2.

8 Ralph H. Crowley (1910) The Hygiene of School Life. London. Methuen and Co. p. 330.

9 Austin Priestman (1915) ‘The Work of the School Medical Officer’ reprinted from The Political Quarterly, no. 8. London and New York. Oxford University Press.

10 A. Châtelet et al. (eds) Open-air Schools: an Educational and Architectural Venture in Twentieth-century Europe. Paris. Focales Editions Recherches.

11 Jane Clarke, ‘Philosophy in Brick’, Inland Architect, November/December 1989. p. 54. For further discussion of Crow Island School, see below, pp. 182–9.

12 MBC rough notes in preparation for British Library interview with Louise Brodie, 1998. IOE Medd collection.

13 Ibid.

14 V. Moriarty (1998) Margaret McMillan: ‘I learn, to succour the helpless’. Nottingham. Educational Heretics Press; Caroline Steedman (1990).

15 Barry Parker also designed buildings for schools including, in 1926, the hall at King Alfred’s School, London.

16 Maurice de Soissons (1988) Welwyn Garden City. Cambridge. Publications for Companies.

17 DLM (2009) ‘A Personal Account. School Design 1945–72’. Unpublished manuscript in author’s possession. p. 2. The Arts and Crafts movement originated in England in the 1860s but became international by the beginning of the twentieth century.

18 Some rough personal notes, MBC, August 1998. British Library, interview with Louise Brodie. List Recordings C467/29/01-06. Mary records Margaret McMillan as an overnight guest in December 1918, MBC diary, 4 December 1918.

19 Ibid.

20 ‘The School System of Gary, Indiana’. Reports by Dr R.H. Crowley and Miss Hilda Wilson, (n.d.) IOE archives, ME/A/1/12.

21 For an account of the school system at Gary, see R. Cohen (2002) Children of the Mill: Schooling and Society in Gary, Indiana, 1906–1960. London. Routledge.

22 Wirt served as superintendent of the Gary public schools from 1907 until 1938.

23 Board of Education Report by Dr Ralph H. Crowley on ‘The School Medical Service in Certain American Cities (1914) p. 15.

24 Ronald D. Cohen in R. Altenbaugh (1999) Historical Dictionary of American Education. Greenwood. Greenwood Press. pp. 387–8.

25 ‘The School System of Gary Indiana’. Reports by Dr R. H. Crowley and Miss Hilda Wilson, Board of Education (1914) p. 207.

26 Board of Education School Hygiene and Medical Inspection in US and Canada. Report by Ralph Crowley, London, April 1914.

27 See below, pp. 34; 38–9; 66.

28 R. H. Crowley ‘Child Guidance Clinics. With Special Reference to American Experience.’ published for the Child Guidance Council by the School Government Chronicle, Child Guidance Clinics, LSE Archives, R/C57 1927. p. 8.

29 An address to the Friends Guild of Teachers, Letchworth, 2 January 1935. Published in The Friends Quarterly Examiner, January 1935. London. British Periodicals Ltd. See also Friends Quarterly Examiner, featuring an article on ‘The Whole Child’ by Ralph H. Crowley, 1935.

30 BL Architects Lives interview tape 1, 1998.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 See R. J. W. Selleck (1968) The New Education: The English. Background 1870–1914. Melbourne. Pitman; W. A. C. Stewart and W. P. McCann (1967) The Educational Innovators. Volume 1 1750–1880. London. Macmillan.

34 Jessica Albery (1908–1990). Lynne Walker, Golden Age or False Dawn? Women Architects in the Early 20th Century. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/content/imported-docs/f-j/women-architects-early-20th-century.pdf. p. 6. Accessed: 20 August 2012.

35 Ibid. p. 13.

36 Beatrice Ensor (1884–1974) co-founder of the New Educational Fellowship (later World Education Fellowship).

37 The Mount School was founded by Yorkshire Quakers in 1831.

38 Isabel Fry wrote two books when she was a young woman. Uninitiated (1895) and The Day of Small Things (1901). She started out teaching in private schools in London, one at the home of the opthalmic surgeon Walter Jessop, in Harley Street.

39 Beatrice Curtis Brown (1960) Isabel Fry 1869–1958. Portrait of a Great Teacher. London. Arthur Barker. p. 31.

40 Isabel Fry’s educational philosophy and practice is described in B. Curtis Brown (1960) Isabel Fry, Portrait of a Great Teacher. The phrase ‘learning by doing’ was used by progressive educators at the time drawing from the work of John Dewey (1859–1952) in the USA.

41 Ibid. p. 61.

42 Ibid. p. 62.

43 Ibid. p. 63.

44 Prof. Dorothy Garrod, in Brown (1960) p. 13.

45 Ibid. p. 65

46 Julian Trevelyan and Mary Fedden, mural at Swallow Dale school, Welwyn Garden City, 1952. Ruth Artmonsky (2010) The School Prints. A Romantic Project. Suffolk. Artmonsky Arts.

47 BL Architects Lives interview, 1998. Tape 1.

48 Isabel Fry was among those who spoke at the New Ideals in Education Conference at Oxford in August 1918.

49 BL Architects Lives interview, 1998. Tape 1.

50 MBC personal papers, ME/A/2/2.

51 Mary was fond of Badley and maintained contact after leaving Bedales. She attended a celebration of his 100th birthday in February 1965.

52 The story of the founding of Bedales is told by John Haden Badley in Badley (1955) Memories and Reflections. London. George Allen and Unwin.

53 Laurin Zilliacus was Chairman of the New Education Fellowship 1946–1959.

54 Badley (1955) p. 166.

55 Henry Swain quoted in Andrew Saint (1987) Towards a Social Architecture. The Role of School Building in Post-war England. New Haven and London. Yale University Press. p. 41. Swain studied at the Architectural Association during the 1930s.

56 C. W. Washburne (1952) What is Progressive Education? New York. John Day Company. p. 80. Washburne served as Superintendent of schools at Winnetka from 1919 until 1943. He visited Bedales during his nine-month tour of European schools in 1923. Like Mary, Washburne’s father was a medical doctor. Washburne succeeded Laurin Zilliacus as World President of the New Education Fellowship in 1947.

57 Badley (1955) p. 183.

58 Carlton Washburne ‘Shall We Have More Progressive Education? Yes Says Carlton Washburne’, The Rotarian Magazine, September 1941.

59 Badley (1955) pp. 206–8.

60 M. Young (1982) The Elmhirsts of Dartington. The Creation of an Utopian Community. London. Routledge and Keegan Paul.

61 MBC diary, Bedales summer term 1924. ME/A/4/31.

62 Zilliacus letters to MBC 1920s–1940s. ME/A/8/22.

63 Rough notes prepared for the interview with Louise Brodie at the BL, 1998, IOE archives, Medd Collection.

64 MBC diary, June 1927. ME/A/4/32.

65 Ibid.