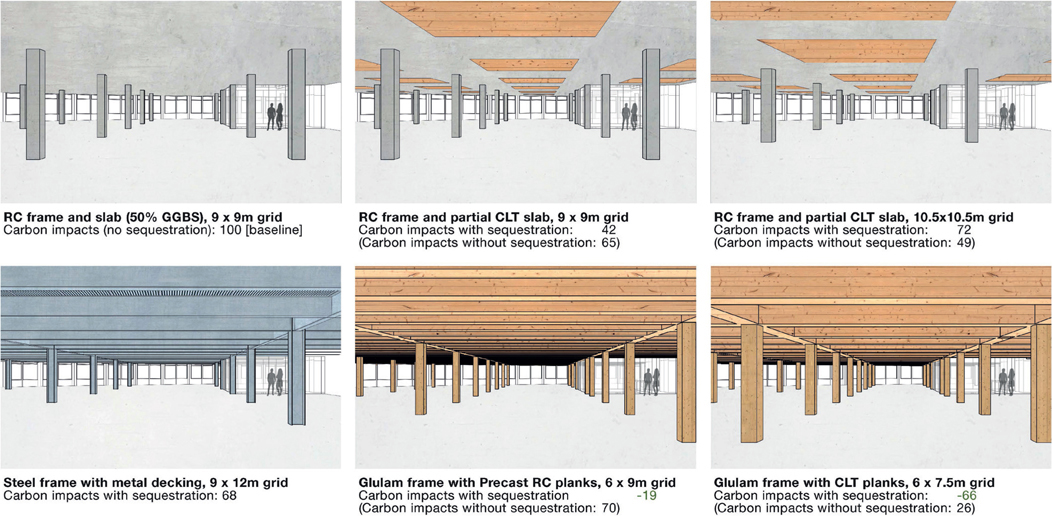

FIG 15.0 (chapter opener) CLT and mass timber are commonly adopted (and expressed to reflect corporate priorities) by high profile commercial clients. Sky’s Believe in Better Building, London (by Arup Associates, 2014) was completed in record time due to early team and contractor collaboration. More so than aspects discussed in preceding chapters, this chapter outlines matters of particular interest to clients and their advisors (and therefore those working with them) that will be regarded differently depending upon the type of client, sector, scale of project, location, form of investment or development or particular moments in time. The only constant is change, it seems, as perception and priorities continue to evolve and shift, often with surprising speed. Clients and developers know better than anyone involved that delivering any development can be extremely challenging and developments that innovate and endure and offer long-term value are certainly no easier. Many are rightly cautious, particularly when it comes to resolving issues around fire safety, acoustics and durability and the priority should of course be to deliver buildings that are safe, comfortable and endure. Concerns may also extend to contractors’ relative inexperience and the potential for this to limit the numbers of interested/able parties at tender stage, adding further pressure to costs. In some instances, CLT will be an appropriate material to consider and in others it may not be. Clients and teams may need work together, taking time to carefully consider options, communicate key issues or listen and evaluate appropriately rather than defaulting to the established way of doing things. A comparative approach is typically adopted, allowing favoured options to be identified and investigated further. FIG 15.1 Simplified visual summary of a comparative exercise considering the differing impacts of various forms of slab construction and grid spacing (headline indicative figures shown with and without accounting for carbon sequestration). In periods of uncertainty and potential change it is even more important to maintain options and retain flexibility where possible. Whilst maximum benefits are typically achieved when CLT use is designed-in from the outset, it is in few parties’ interests to preclude particular actions (whether that be insisting on CLT use or ruling it out) until sufficient investigations have been undertaken to make the best decisions. A key constraint is often time. Project experience suggests that decisions around structural materials are often made early in the process, while resources are limited and perhaps before a full team is engaged. Fledgling teams exploring any approach that is not widely adopted will rightly be asked to justify design direction or materials choices, typically responding to specific technical issues, at short notice. As such, undertaking early research into CLT use may help understand whether it offers value to a project and this is a great opportunity to explore projects in other regions and countries where experience may vary.1 Engaging specialists can also be important – seeking out parties with relevant experience, engaging the supply chain in a meaningful way and bringing them to the project in any way possible early on will also inform better decision making. Whatever material is under consideration, one of the most common questions posed when considering relatively new forms of building or construction is ‘show me examples where it’s been done before’. Since many of the buildings completed with CLT to date have been developed by innovators and early adopters, such leading edge individuals and organisations are typically minded to share lessons learnt to benefit the early majority and those following afterwards. Seek out relevant precedents and contact those involved to learn more. Resources such as this book and others referenced can signpost completed projects and sources of further information and help teams understand the scope and scale of a range of issues. Established specialists and industry trade associations are typically well positioned to assist and keen to help decision makers cross the perceived chasm from innovation to wider adoption and frequently publish precedents and guidance on a range of issues. This is of course not always possible if proposals are novel and particularly with commercial buildings, there are many diverse ways of making use of CLT and many emerging structural solutions as further hybrid options are developed. As a last resort, mock-ups and tests can be undertaken to validate designs and achieve necessary certification or reassurance if the investment can be justified. Private residential clients continue to drive interest in innovative new materials and this sector produces a large number of CLT buildings where early innovators are less burdened by institutional views or the obligations and perceived risks associated with large buildings. Feedback from owner-occupiers is typically very positive and although this should be expected (given most have made significant personal investments in a bespoke home to suit their own interests and priorities), it seems that the emotional response to exposed timber from owners and visitors alike is almost universally positive. Many in the UK will consider the use of CLT in multi-storey/multi-family residential to be off-limits due to post-Grenfell regulatory changes to Building Regulations. It should be noted that subject to other established design approaches, combustibility restrictions are proscribed to elements within the external wall only. Large-scale residential schemes such as Brock Commons or the Australian National University, as illustrated within this book, offer proof that external wall elements can be readily incorporated with lower impact CLT superstructures in a way that would meet current UK regulatory requirements. Any new approach will deservedly attract the keen attention of those underwriting risks and CLT take-up is no exception. Concerns will likely be raised around issues of fire safety (including during site works) and durability – particularly in terms of long-term asset value. This is not an issue that should be avoided and early engagement with warranty providers, insurance providers and others to help inform other decisions (rather than afterwards) will be time well spent. In doing so, be specific in raising any concerns, whether relating to the perception of risk or actual risks to life safety, building fabric or business continuity. Such engagement can help all parties better understand actual risks and may provide opportunities to explore or alleviate concerns over specific issues. A thorough approach at this stage will minimise abortive work if particular arrangements are deemed to be unacceptable in time. Development decisions reflect a huge range of considerations beyond just cost but developers and contractors are prompting teams to explore and consider value from CLT use in other ways. Programme savings are a great example where CLT panels, which likely cost more than conventional materials, are lifted and installed quickly, in panels sized up to 50m2 at a time. The impact on site programmes, preliminaries and secondary costs can however be significant and should be calculated and considered.2 Beyond issues discussed within the cost and values chapter, developing a story explaining the benefits of materials choices and design decisions can be key. This is frequently raised by agents who might typically want to know ‘what’s the story?’, ‘what are the three headline issues that will appeal to investors or tenants?’, i.e. ‘what can I sell?’. Any metrics supporting such narratives (and more importantly informing the preceding decision-making process) will always be put to good use. Until relatively recently, briefing and early stage sustainability aspirations may have focused primarily on driving down boring-but-worthy operational energy. This agenda offered little joy but plenty of restrictions and requires difficult structural change to make significant improvements beyond established (low) performance benchmarks. Over time, focus shifted to more conspicuous, more tangible issues around occupant health and wellbeing. Such aspirations are undoubtedly more readily achievable, easier to sell and create a much more positive image for occupants to buy into. As demonstrated around the time of Brexit, there was a very significant upsurge in the awareness of, and stated concern about, environmental issues by businesses as well as individuals. This was due perhaps to a wider recognition of the climate emergency, the rise of high impact social movements such as Extinction Rebellion, global school strikes, and the adoption of (and in short order, subsequent improvements of) net zero carbon ambitions by nations, regions and leading corporations, including for the first time serious widespread discussion of zero embodied impacts from construction. One of the most dramatic consequences of this is a marked change in attitudes regarding real estate development with agents, clients and funding bodies recognising potential risks to capital and placing a much greater emphasis on issues around environmental impacts.3 Net zero carbon considerations are now frequently front and centre for funders and investors, developers, owners and occupiers in a way that would have been unimaginable only a few years earlier – presenting a marked shift even during the time it has taken to compile this book. There is now an increasingly common appreciation that developments should be considering and addressing embodied carbon impacts and although these are not typically well-defined or understood, this has led to a dramatic upsurge in interest of CLT. This may be in part because using CLT conspicuously, i.e. on display, may be seen to address issues of wellbeing, natural materials, biophilia and a better internal environment and still be associated with a meaningful carbon impact (do also bear in mind that CLT need not be on display to provide myriad advantages to a project – this is often overlooked with a common fixation on visual aspects). Carbon accounting of impacts across both development portfolios and tenant estates is now commonplace and after years of building awareness, client bodies are seriously addressing embodied carbon impacts with the understanding that doing so will likely increase capital expenditure. Legislative and/or fiscal incentives may well follow to ensure industry moves towards national net zero carbon targets but when increased reporting around such issues is commonplace, financial institutions are proving keen to change direction to protect future value. Funding bodies realise that if the market moves to lower impact buildings as it appears to be doing then most present day developments may be very unfavourably compared to newer, smarter alternatives. This may take place within a relatively short period of time – potentially the next property cycle. While lower impact buildings may or may not attract a premium, either way, it is possible that higher impact and therefore prematurely outdated and unwanted buildings may be devalued, risking becoming stranded assets, seen as dinosaurs from a previous age. Key questions to ask at the options evaluation stage may explore the scope of carbon impacts to be evaluated, whether considered as part of a longer term, circular approach or a more limited, shorter term linear view: Universities understand acutely that they will be judged on the quality of their campus assets and learning environments and for this reason, many of the bespoke CLT exemplars around the world (and indeed high quality/superior performance learning spaces) have been developed by the higher education sector. Students will in turn progress to the commercial workplace and in a market competing for talent will not be impressed by companies offering less attractive environments than they may be used to. This may be most apparent in the tech sector where interest in mass timber buildings has been particularly significant and huge buildings are currently on site for Google and Microsoft and under consideration by many others. Whether or not they are interested in how a building is put together, many agents recognise the benefits of good quality, high visual impact spaces and are amongst the best advocates for mass timber buildings. They might understand that the use of CLT and related materials reflect broader societal concerns on many levels and are more aware of the basic emotional response to timber that is typically positive, and therefore good for business. In researching this chapter, discussions with residential clients and commercial agents alike kept coming back to the positive emotional effect of timber use on occupants and users of buildings. Whether teams have the appetite to try and address some of the challenges we face or whether they are more concerned by the preferences of others, it is hoped that this book has helped identify key issues and highlighted further opportunities when considering this exciting new material.

CHAPTER 15

CLIENT ISSUES

THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

Investigating potential options

Pressured decision making

Existing precedents

Residential clients

KEY ISSUES AROUND THE CONSIDERATION OF CLT

Risk managers, insurance and warranty providers

Considering value as well as price

Telling the right story

Environmental and financial priorities

Carbon accounting and reporting

New workers’ expectations

Emotional response to timber