Interlude D

Transformative power of Architecture

Steven Holl

I believe in the social contract, therefore I teach. I believe the university is one of the last places that protects and preserves freedom; therefore teaching is also a sociopolitical act, among other things.1

John Hejduk

Trying to make sense out of what we are doing as architects today requires a reexamination of values. It requires asking, what are our core values? Questions of ethics might be considered.

This world’s social inequity, where roughly one-third of all people on the planet live on less than two dollars per day, and unprecedented environmental degradation set architecture in a particular twenty-first-century framework. Unlike the modern architects of the early twentieth century, we should have a new global view. Today, we have unparalleled and comprehensive information about our fragile planet. As architects, we face our limitations with concrete geometric desires – yet we want our aspirations to have meaning. We try to imagine ideals and make idealistic proposals for particular situations. However, ambiguous circumstances prevail.

The ambiguities of cultural and economic change are compounded by record environmental and climatic change. Are there also fundamental epistemological changes? Let’s assume we can still reflect on ethics in a similar spirit as Kropotkin did in his Ethics: Origin and Development.2 Kropotkin removed ethics from religious and metaphysical spheres and placed ethical teaching back in the natural environment and the everyday world. He asked questions significant in the life and thought of all beings. For Kropotkin, a basis of human ethics was the “physics of human conduct.” He saw ethics not as an “abstract science of human conduct but a concrete scientific discipline whose object is to inspire humans in their practical activities.”3 As one of the responsible and practical arts, architecture is challenged with inventing new possibilities. Architecture’s potential to unburden life lies in its invention.

Today fundamental questions concerning prominent architecture are rarely asked. Instead we are inundated with information, much of it useless. Today architecture is viewed in a rapid fire of narrow screen images. Flashes of new buildings irrespective of site or local culture are, as Pérez–Gómez notes, “equivalent to a mindless search for consumable novelties.”4

An alternative is to reinvent specific architecture case by case. Each work of architecture is organized as if to build its site. Rather than an object occupying a site, specific architecture is inspired by its site. This can be an ethical aspect of focusing architecture on social dimensions. As I have described in previous text,

Architecture is bound to situation. Unlike music, painting, or literature, a construction is intertwined with the experience of a place. The site of a building is more than a mere ingredient in its conception. It is its physical and metaphysical foundation.5

Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Juhani Pallasmaa and I carried these thoughts much further in our collection of essays in the Questions of Perception with Professor Pérez-Gómez continuing the cause, when he clearly states that, “The cultural specificity of practices in our global village is absolutely crucial.”6

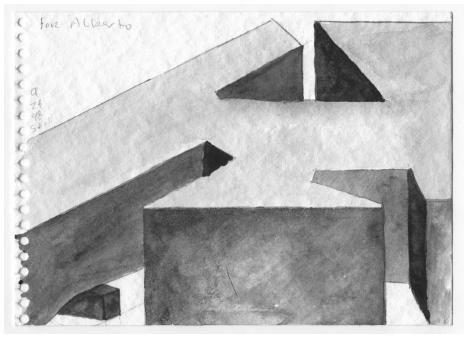

Figure D.1 For Alberto, Steven Holl

There is a transformative power to architecture. Architecture has much more to offer than pragmatic solutions to problems of the environment or technical solutions to programmatic needs. As Pérez-Gómez argues, architecture “incites us to real meditation, to personal thought, and imagination, opening up the space of desire … unveiling a glimpse of the sense of existence.”7 He argues for the urgency of the poetic imagination of the architect, wherein lies the potential of the real transformative power of architecture in the twenty-first century. In Pérez–Gómez’s words, “works of architecture, art, and poetry are indeed capable of moving us; they transform our life and ground our very being.”8

Notes

1 Herbert Muschamp, “John Hejduk, an Architect And Educator, Dies at 71,” New York Times, July 6, 2000.

2 Prince Kropotkin, Ethics: Origin and Development, trans. Louis S. Friedland and Joseph R. Piroshnikoff (New York: The Dial Press, 1924).

3 Ibid., xiii.

4 Alberto Pérez–Gómez, “Relevance of Beauty in Architecture,” in Cultural Role of Architecture, ed. Paul Emmons, John Hendrix and Jane Humolt (New York: Routledge, 2001), 164.

5 Steven Holl, Anchoring: Selected Projects, 1975-1988 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1989), 9.

6 Alberto Pérez–Gómez, “Relevance of Beauty in Architecture,” in Cultural Role of Architecture, ed. Paul Emmons, John Hendrix and Jane Humolt (New York: Routledge, 2001), 165.

7 Alberto Pérez–Gómez, “Architecture and the Body,” in Art and the Senses, ed. Francesca Bacci and David Melcher (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 576.

8 Alberto Pérez–Gómez, “70 Architect(e)s … longing for beauty and the common good,” in 70 Architect(e)s: On Ethics and Poeti