Dammam, Saudi Arabia

The Dammam Metropolitan area is located in eastern Saudi Arabia along the Gulf seashore, in the most oil-rich region in the world. Today it comprises a number of cities, including Dammam, Khobar, Dhahran and Qatif, as well as a cluster of smaller towns and villages. This new urban conglomeration sits on the coast just to the northwest of the island archipelago which forms Bahrain. Indeed, Dammam itself was only formed in 1923 when a group from the Al-Dawaser tribe decided to move from Bahrain to the mainland, where King Abdulaziz allowed them to settle. They split into two groups and created separate fishing villages in Dammam and adjacent Khobar. These two villages began with slow development until 1938 when Saudi Arabia started exporting oil in commercial quantities (the county’s formation into a modern kingdom had only happened in 1932).

As a result, the Dammam region witnessed continuous urban growth in the second half of the 20th century, even if initially it wasn’t enough to bring all the urban centres together. Just two decades ago, the cities and towns in the region still remained scattered and a sense of urban connectivity did not really exist. The term ‘Dammam Metropolitan’ has therefore emerged due to the huge developments that have taken place since the 1990s, especially after the municipality decided to build a unified seafront along the whole shoreline. Now it is difficult for anyone to identify the boundaries between Dammam and its neighbouring centres: the area has become a large urban mass connected by major highways and real estate projects which all make it look and feel as if it is just one big city (see Plate 5).

The urban structure of the area can thus be considered as young, because all of its cities – excluding Hofuf and Qatif (along with a few older villages) – only really got started in the fourth and fifth decades of the 20th century. Indeed, it could be said that the origin of contemporary settlement in this part of Saudi Arabia stems from when Aramco (the Arabian-American Oil Company, now Saudi Aramco) built its initial housing projects in ‘camps’ for oil workers in the eastern part of the country from 1938–1944; the first ever was in Dhahran, close to Dammam.1 These estates introduced for the first time a new concept of space and a new image of the Saudi home. It is possible to say that this early intervention had a deep, if not immediate, effect on the native population: it certainly made them question what they knew and how they should behave in their domestic environments. In other words, this initial change can be seen as the first motive for social resistance to new urban forms and imagery within the contemporary Saudi built environment. We should also mention here the impact of the railway which was constructed in 1951 to connect Dammam with Riyadh through Al-Hassa. That project was crucial because it encouraged many people from central Saudi Arabia to move to the under-populated Dammam region and build up their businesses there.

The significant impact of this experience presented itself in conflicts between the old and new in local Dammam society. Threats from interfering outside elements to social and physical identity created for the first time in Saudi Arabia a social reaction towards the physical environment. The conflict between traditional cultural values and the introduction of western forms and images was limited at the beginning of the period of modernisation; indigenous people followed what they already knew and tried to continue to implement it in their daily lives, including their homes. However, this emerging contrast between traditional images and newer westernised images in the minds of local people can also be considered the beginning of important physical and social changes in the Saudi built environment.

This chapter therefore tells the story of development in this eastern part of Saudi Arabia. Its main goal is to investigate how urban identity in the region has gone through transition during recent decades, and how this has influenced the ‘acceptance’ and ‘use’ of urban structures. The text here will concentrate on people’s lifestyles within their home environment in relation to the wider transformation of urban structures. For this purpose, I have for many years been conducting fieldwork studies to trace urban changes in Dammam and find out how people respond to them. Social, economic and political changes must all be seen as major factors in the analysis of the impact of urban change on cultural identity.

4.1 Dwellings in the Dhahran ‘camp’ formed by the Aramco oil company

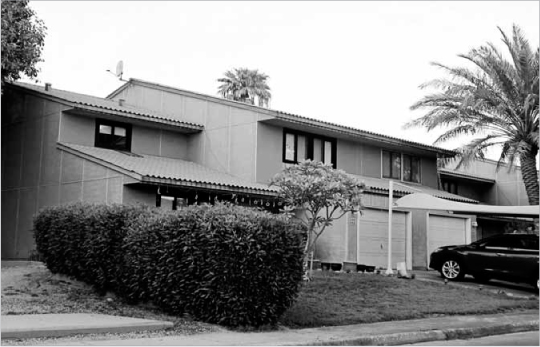

4.2 House in the Dhahran ‘camp’

4.3 House in the Dhahran ‘camp’

FORMATION OF THE ‘DAMMAM METROPOLITAN’ REGION

The first indication of a conflict between local culture and western culture can be ascribed to Solon T. Kimball, who visited the Aramco headquarters in 1956. He described how the senior staff members at the (American) ‘camp’ in Dhahran were completely imported from United States:

Not one westerner would have difficulty in identifying the senior staff “camp” as a settlement built by Americans in our southwestern tradition of town planning. It is an area of single-story dwellings for employees and their families. Each house is surrounded by a small grassed yard usually enclosed by a hedge.2

This American camp, intended for senior oil workers, and which introduced its own new spatial concepts, contrasted strongly with the surrounding home environments found in the existing old cities in the region, Hofuf and Qatif.

In face of such developments, native Saudi people still persisted with their own spatial concepts and images, tending to resist the imported ones. They considered the latter as strange things. Therefore, whenever Saudi workers and their relatives ‘moved in, they took over any empty land available and erected basic shelters and fences of locally available material, separated from each other by narrow irregular footpaths.’3 This created ‘a community of mud-brick and timber houses, built in a traditional and comfortable way’.4 During his visit in the mid-1950s, Kimball noticed this alternative community growing up, and described the Saudi camp built adjacent to the senior staff camp as ‘neither planned nor welcomed … these settlements represent the attempt by Arabs to establish a type of community life with which they are familiar.’ Kimball openly recognised the insistence of native people on their own identity through his description of the Saudi camp as ‘an emerging indigenous community life’.5

4.4 General view of the city of Dammam

4.5 General view of the city of Khobar

We should mention here that in the first two decades of change a number of alterations appeared in local Saudi people’s attitudes towards their homes. What Kimball observed was the stance of the native population at their first point of direct contact with western culture. Saudi people, at this stage, refused to accept change and simply stuck with what they knew. This is not to say that the new westernised images did not also influence people; however, they were still in the process of developing a new attitude towards how they lived in their homes. An attitude had not yet been formed to reflect just how deeply the new forms and images broke the old idea of the Saudi home.

The Saudi government and the Aramco oil company were not at all happy with the presence of the alternative traditional-style settlements in the oilfield areas.6 Even as early as 1947 the government had asked Aramco, which employed American engineers and surveyors, to try to control the growth of the unwanted settlements. This led to the first planned cities in Saudi Arabia, carried out on a grid-iron pattern, in Dammam and Khobar.7 The spatial concepts and building forms which were introduced into these two planned cities accelerated the impact of westernised modern architecture on local people, not just in these two new developments, but also in surrounding older cities in the Dammam region.

The main characteristics of urban development in Dammam and Khobar were, as noted, based on the western principles of grid-iron land subdivision. These two cities were divided into a number of almost-square blocks surrounded by wide streets, as a form of ‘domino planning’. The blocks were generally around 40–60 metres in either direction, and in the city centre areas at least were orientated in a northsouth direction. Both the new street pattern and structures built on them were totally new, and as such they shocked local people; yet at the same time it started a transformative urban era which led in time to complete urban and social change. The Saudi government allocated some entire blocks to extended families that moved into the new cities and built new neighbourhoods within the planned urban structure. It is difficult now to track precisely how the social urban identity of the new developments were formed, but what certainly happened is that a mix of old and new values and lifestyles came to be created in these areas. We can thus attribute the sense of urban identity of the Dammam Metropolitan region today to this formation of a modernised fabric from the late-1940s and 1950s.

4.6 Apartment block with shops below on King Saud Street, Dammam

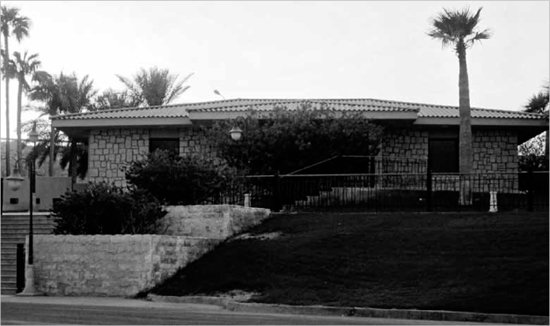

As mentioned earlier, the new type of house that was built, which became widely known as a ‘villa’, was imported originally from western countries and built on oil bases. But it was a type which developed further in the 1950s when the Aramco Home Ownership Program compelled local Saudi workers to submit designs for their houses in order to qualify for a building loan from the company.8 People had to rely upon Aramco’s architects and engineers to design their new houses because there were so few architects in Saudi Arabia at that time.9 In order to speed up the approval process, Aramco’s architects and engineers developed several standard design alternatives for employees to choose from. However, all these designs adopted a style loosely described as the ‘international Mediterranean detached house’.10

4.7 Apartment block on King Saud Street

4.8 Close-up view of apartment balconies on King Saud Street

This hybrid kind of villa house soon spread into the two new planned cities in the eastern region, Dammam and Khobar, especially in neighbourhoods which constituted the original historic settlements.11 To give one example, Al-Said has studied the growth of the old Al-Dawaser neighbourhood of Dammam.12 He found that, between 1930 and 1970, this neighbourhood grew from 56 to 250 residential units, and that these were ‘mostly typical courtyard residential units as a result of contentious house subdivision and room addition’.13 The situation was similar in Khobar, where the house style was more influenced by the prevailing traditional styles in the region. So even though many modern developments appeared in these two planned cities due to Aramco’s programmes in the 1950s and 1960s, many residents, especially in the older settlement areas, insisted on using a more traditional variant of the house form.14

It can be argued that Saudi people, in that period, were still strongly influenced by their previous cultural experience, and were able to express this loyalty very easily since the full force of modern building regulations was not yet being applied. This meant that people had greater flexibility to decide the form of their houses. It is important to note here that most Saudi Arabians still retained a strong connection with their social, physical and aesthetic traditions, all of which were then strongly reflected in their domestic environment.

The new architectural image that spread through the planned cities was mainly of concrete buildings with neat crisp facades and balconies. Three-, four- and five-storey buildings appeared rapidly on the main streets – such as King Khalid Street in Khobar and King Saud Street in Dammam – during the 1950s and 1960s. The new urban form was very striking to local people compared to what they had been used to in the older cities. Furthermore, from 1960 to 1980 an entire range of abstract westernised building forms was developed in the Dammam region, often for very commercial purposes. The urban and architectural developments of the time created a real crisis of architectural identity which became one of the main issues debated amongst Saudi intellectuals by the 1980s.

THE SPREAD OF A MODERN BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The desire to create a modern country in a short period of time therefore brought about total physical change to most Saudi cities.15 As in other Middle Eastern countries, the process of modernisation in Saudi Arabia ‘is largely physical and heavily imitative of the western model’s external departments and lifestyles’.16 This is today manifested in unified governmental planning policies throughout the Saudi kingdom. However, prior to the 1960s, most attempts to regulate and control the growth of Saudi cities were partial and had limited impact.17 By 1960, however, the first proper building regulations were issued in the form of a circular by the Deputy Ministry of Interior for Municipalities.18 This circular, as Al-Said mentions, was:

… the turning point in Saudi Arabian contemporary built environment physical pattern and regulations. It required planning of the land, subdivision with cement poles, obtaining an approval for this from the municipality, prohibited further land subdivision, controlled the height of the buildings, the square ratio of the built [area], required set-backs, [and so on].19

Still, such regulations took a further fifteen years until they came to be regularly applied in all Saudi cities. This can be clearly seen in the configuration of the master-plans that were initiated for all Saudi regions between 1968 and 1978.20 One example was the first master-plan for Riyadh as executed by Constantinos Doxiadis from 1968–1973.21 His scheme reinforced the existence of the set-back regulations and applied a rigid planning system similar to what had been used already in Dammam and Khobar. Doxiadis therefore confirmed the notion of the grid as the most desirable pattern to be followed, not just for the planning of Riyadh, but for all other cities in the country.

Despite the fact that the Saudi built environment witnessed the gradual imposition of tighter building regulations from the 1960s, their actual impact didn’t at first really influence the forms of houses or their surrounding urban spaces. This was because the authorities had not as yet developed proper institutions to follow up on the regulations.22 However, with the establishment of the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MOMRA)23 and the Real Estate Development Fund (REDF) in 1975, the Saudi government demonstrated that it was aware of the need to monitor the construction of private houses which benefited from state loans.24 In practice, the strict application of the building regulations through such measures ‘institutionalised’ the hybridised villa as being the only acceptable house type in Saudi Arabia.25

We can also now see in retrospect that steps being taken by the Saudi government to control urban spread in the new planned cities of Dammam and Khobar led in 1975 to the commissioning of Candilis Metra International Consultants to update the proposals for the region. This entailed the reinforcement of the original grid-iron urban pattern, and sent a clear message to the population in the adjacent older cities, Hofuf and Qatif, that Dammam was now the ‘free place’ where they could acquire new lifestyles in a modern urban image. This led many people to move to newer areas to establish their own lives away from complicated traditional social values and ties. From 1975 through to 2000, constant waves of migrants from these surrounding cities and from different parts of Saudi Arabia brought in the people needed to occupy the growing mega-urban structure of the Dammam Metropolitan region.

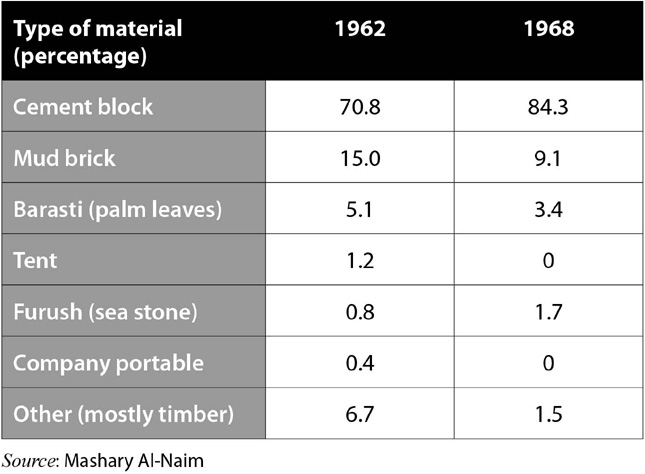

It is important at this point to consider the position of Saudi people in relation to such rapid developments in the built environment. If we go back to the beginning of this period of change, we can argue that Aramco’s oil bases in the eastern region, in general, and the company’s home ownership programme, in particular, should be considered as the origin of the formal and cultural contradictions that appeared later in Saudi people’s home environments. The housing style imposed by Aramco’s programme from the 1950s continued to have a powerful impact through to the 1970s, especially once Saudi building regulations were working to support and indeed encourage it. This could be seen clearly by the fact that owning a new detached ‘villa’ in Saudi Arabia became an important social symbol of personal and social identity.26 There was also a similar consolidation of building materials towards more western materials, as shown in the table opposite.

We can attribute this emergence of a new symbolic role for the villa-type house to the appearance of a substantial Saudi middle class in the 1950s. This class included a mixed group of people from all over the kingdom, but in the main they were employees either of Aramco or the Saudi government. These people were characterised by their level of literacy and experience of modern materialist culture.28 As a middle-class group, they ‘brought about cultural contact between Saudi society and the Western world’,29 and tended to express their new-found status by residing in the latest dwelling type, i.e. the westernised villa.30 Due to their greater contact with other cultures, members of the Saudi middle classes were strongly influenced by the villa-type housing which had spread throughout the Middle East during the colonial era, and which was thus associated with people at the highest levels of administration31 (see Plate 6).

Table 4.1 Construction materials used by Aramco’s employees in 1962 and 196827

The villa hence represented an image of modernity, and Saudi middle-class attitudes were based on ‘the stylistic association that “modern”, as expressed in the modern villa style, is “good”, by virtue of being modern’.32 The villa’s ability to present a sense of individual identity and originality through the seeming uniqueness of design may also have led to its rise in popularity, given that the conformist habits of traditional society were beginning to be seen as ‘backward’. In this mindset, any statement about individualism was regarded as ‘modern’ and therefore intrinsically ‘good’. Jomah has noted the sense of formal individualism that distinguished house design in the cities of Mecca, Jeddah and Medina from the mid-20th century onwards. He considers these styles to be representative of a shift from a ‘tradition-directed’ to a ‘self-directed’ pattern of social organisation.33 In his view, ‘the concept of home was … reduced from the traditional spiritual home to the modern physical and spatial one’.34

4.9 Luxury villa-type dwelling in Dammam

4.10 Villa-type dwelling in Dhahran

A NEW URBAN IDENTITY FOR DAMMAM

Throughout all human societies, people surround themselves with specific objects to communicate with other members of their community. The need to express a common meaning through one’s home environment encouraged the villa type to become the device which enabled Saudi middle-class families to express their new social status. In that sense, the home can be seen as a dynamic dialectic between individuals and their community.35 While the Saudi middle-class family expressed its wealth and modernity by owning and living in a villa, they also used the uniqueness of their villa form to represent their own personalities.36 People from different regions of Saudi Arabia who have settled in Dammam often recall images from their region of origin. This also reflects the desperation of designers to create a sense of continuity within the contemporary built environment in Saudi Arabia.

Our general desire to recreate traditional images has been discussed by Rybczynski. He writes: ‘This acute awareness of tradition is a modern phenomenon that reflects a desire for custom and routine in a world characterized by constant change and innovation.’37 The impact of external forms on people’s self-image is a result of the strong connection between what the eye sees and how the perceived environment is interpreted. People tend to evaluate the visual quality of the surrounding environment according to their past experiences. In that sense, the sentimental reaction towards traditional images in Saudi Arabia can be attributed to the sadness and emptiness felt by people at the loss of these images, rather than as an expression of their actual cultural identity.

Another important issue is that the planned Saudi cities from the late-1940s, typified by Dammam and Khobar, passed through huge transformations that altered the form, height and styles of buildings found in them. Many blocks also passed through a series of changes of ownership, and as such were divided into smaller parcels. This shows two streams of urban identity working side-by-side in Dammam: one searching to retain a historical image, the other tending to reinforce the idea of modern urban identity. What has happened on the ground in the region in the last two decades has only increased this cultural and architectural conflict.

4.11 Dammam’s urban development along the coastline

4.12 General urban development in Dammam

4.13 High-rise apartment blocks in Dammam

4.14 Westernstyle supermarket in Dammam

More recently still, a surge in development in the region has led, as noted, to an ever wider urban expansion. Plenty of new neighbourhoods were constructed in the last two decades to meet the population growth. Compared to the surrounding older cities, especially Qatif, urban and social identity has undergone incredible transition in Dammam. The different cultural backgrounds of newcomers to the area, along with the presence of huge number of expatriate labourers, have heightened this crisis of identity. For example, it is rare today that we find local Saudi people walking in the centres of these cities; those who are on the streets are mainly Asian workers collected together in huge numbers, which gives a very different impression to any visitors to Dammam or Khobar. What is especially interesting, and different, is that the older cities in the region have also been transformed from an urban perspective, but to a much greater extent they maintain their traditional social structure, ending up as a clear visual contradiction.38 In these older centres, people have insisted on expressing their previous value systems even if they also ended up transforming their houses. It is also noticeable that there are relatively fewer overseas workers in the older settlements such as Qatif, when compared to Dammam and Khobar.

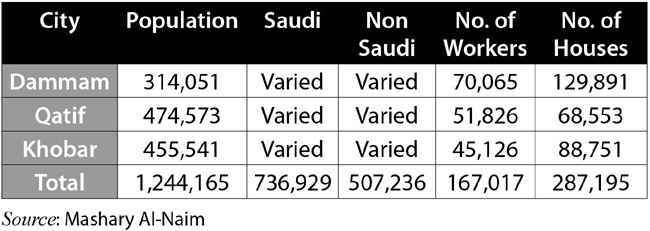

Table 4.2 Population statistics for the Dammam Metropolitan region (2007), based on data from the Central Office of Statistics and fieldwork by the author

4.15 New office block under construction in Dammam

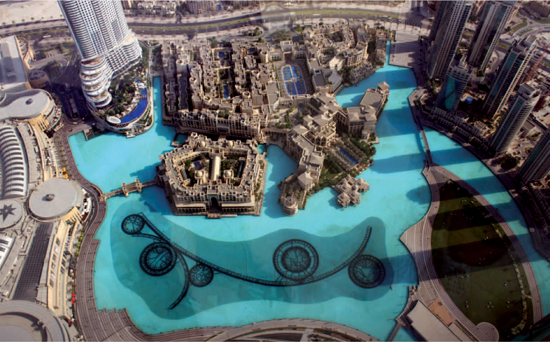

Urban projects in the Dammam Metropolitan region in the last two decades, including the seafront development and the construction of major freeways, have created very different lifestyles even since the 1980s. These buildings alter the whole structure of Dammam and Khobar, while contributing greatly to the new urban identity. Contemporary architectural practices show a tendency to commercialize the skyline of the cities by encouraging high-rise buildings spread along main highways and in the urban centres. This phenomenon has been associated with the economic prosperity of the last decade caused by the steady increase of global oil prices. We cannot deny also the impact of Dubai, which has influenced most Arab cities, including those in the Saudi Gulf region, to build upwards.39 Competing with Dubai means for many officials in cities such as Dammam that the building of high-rise towers becomes the way to show their cities are equally as developed and modernised as Dubai.

The impact of the current global financial crisis – which has proved so dramatic for Dubai – has however been very limited in Dammam. This was because those involved in urban development in Saudi Arabia were very alert to the financial problems, and because urban growth has been more measured compared to that in other Arab Gulf cities. Although urban development was expedited because of the rising oil prices, the process nonetheless remained relatively controlled in Saudi Arabia. This has helped the ‘Dammam Metropolitan’ region to absorb this latest financial crisis, as reflected in its urban activities. Not a single project was cancelled or delayed in Dammam, and new projects are still being commissioned. Saudi people still clearly believe in investing in property, and real-estate projects have thus continued.

4.16 Recently completed housing blocks in Dammam

4.17 Zamil House office block in Khobar

4.18 Another new office block complex in Khobar

CONCLUSION

The Dammam Metropolitan region can be considered as the main gateway for Saudi Arabia onto the Gulf. It is therefore also the base for the country’s oil industry, providing it with an important role within the Saudi and international economies. This part of the Gulf region must be seen as new, with its history not really stretching back beyond seven decades. This sense of novelty has also been reflected in the absorption of new forms and images in cities like Dammam, and a very different urban identity has been formed as a result. However, a continuing crisis of cultural and architectural identity is still being felt by local people, even if this was never as harsh in Dammam as in older cities like Qatif, or indeed elsewhere in Saudi Arabia. Rapid growth clearly contributed to what we can call an ‘image instability’ which has weakened the sense of urban memory. This is what has led to continuous tension between historical collective memory in Saudi Arabia and the pressure to adopt a more modern image.

The relatively youthful age of the urban structure of the ‘Dammam Metropolitan’ region makes it more possible for inhabitants to accept social change, and the new architectural images that accompany it, and so the city has shown very low ‘resistance’ to these forces. This can be seen as a positive dimension that allows the city to take a lead in urban modernization in Saudi Arabia. What has happened in the past few decades shows how Dammam can go along with new forms and images, precisely because its urban structure is a product of western modernist planning and land subdivision. Dammam’s ability to renew its urban identity in such a short period of time should be considered an important hidden potentiality within its urban structure. Ever since its new urban structure was first introduced in the late-1940s, the city has undergone many changes, and every time it extends its urban fabric without difficulty. Today, new towers are growing up easily within the urban structure. However, many visual contradictions and tensions do continue to appear, especially in residential neighbourhoods, due often to the mix of cultural backgrounds of residents who come from different parts of Saudi Arabia or from other countries in the world. It all makes for a richer social and architectural combination.

NOTES

1 Aramco built its first camp in Dhahran in 1938, followed by one in Ras-Tanura in 1939, and Abqaiq in 1944. See: Saba George Shiber, ‘Report on City Growth in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia’, in Saba George Shiber, Recent Arab City Growth (Kuwait: Government Printing Press, 1967), p. 428.

2 Solon T. Kimball, ‘American Culture in Saudi Arabia’, Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 18, no. 5 (1956): 472.

3 Shiber, Recent Arab City Growth, p. 430.

4 David Shirreff, ‘Housing – Ideas Differ on what People Want’, in John Andrews & David Shirreff (eds), Middle East Annual Review 1980 (Essex: World of Information, 1979), pp. 59–62. Saleh Al-Hathloul has also said: ‘The initial growth of Dammam and Al-Khobar in the late 1350s[H]/1930s and early 1360s[H]/1940s was not planned in an orderly fashion. As the population grew, people took over any available land and erected basic shelters and fences of local materials. Following the traditional pattern of Arab-Muslim cities, the streets were narrow and irregular.’ See: Saleh Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change in the Physical Environment: The Arab-Muslim City’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 1981), pp. 145–146.

5 Kimball, ‘American Culture in Saudi Arabia’, p. 472.

6 Ibid., p. 473.

7 Shiber, Recent Arab City Growth, p. 430. He describes the plan of Khobar thus: ‘It covered only about one quarter square mile north of the company pier head storage yard. The blocks averaged 130 by 200 feet with separating streets of 40 and 60 foot widths.’ Moreover, he indicated how the new plan ignored the existing Saudi settlements: ‘Here again, the gridiron pattern was oriented north-south. No consideration was given to the mushroom growth of temporary structures and those were demolished to open the new streets.’ See also: Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, p. 146.

8 Roy Lebkicher et al., Aramco Handbook (New York: Arabian American Oil Corporation, 1960), pp. 212–216; Shiber, Recent Arab City Growth, p. 431; Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, p. 167.

9 Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, p. 167.

10 Saleh Al-Hathloul & Mohamed Anis-ur-Rahmaam, ‘The Evolution of Urban and Regional Planning in Saudi Arabia’, Ekistics, vol. 52, no. 312 (May/June 1985): 206–212.

11 In the 1920s, two small fishing settlements were established in Dammam and Khobar and occupied by members of the Al-Dawaser tribe. See: Fahad Al-Said, ‘Territorial Behaviour and the Built Environment: The Case of Arab-Muslim Towns, Saudi Arabia’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, 1992), p. 217.

12 Ibid., p. 225. The original settlement was described by the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MOMRA) in 1981 thus: ‘The dwelling unit and clusters were added onto or joined to one another according to needs of the inhabitants. Neither the open space nor circulation pattern was predetermined. They resulted from the accidental disposition of dwelling units and the definition of family territorial holdings.’

13 Ibid., p. 234.

14 Ibid. In the 1960s Dammam municipality had the power to apply Aramco’s desired building regulations. However, this was applied only for the Aramco neighborhoods. Al-Said said, ‘even though Dammam municipality has complete control over its streets and building regulations, the neighbourhood has only been affected by the creation of a major street … in the north, and the winding of the south street’.

15 This phenomenon is found in most Arab countries which tried to achieve modernity rapidly. Lerner mentioned this issue, saying: ‘what happened in the West over centuries, some Middle Eastern now seek to accomplish in years.’ See: Daniel Lerner & and Lucille W. Pevsner, The Passing of Traditional Society: Modernizing the Middle East (Glencoe, NY: Free Press, 1958), p. 47. This rapid change, coupled with a lack of local design and construction firms, served to accelerate the gap between traditional culture and the new westernized culture being introduced in the Saudi domestic environment.

16 A.B. Jarbawi, ‘Modernism and Secularism in the Arab Middle East’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, 1981), p. 21.

17 In an interview with Dr. Said Farsi (the former mayor of Jeddah) in the Saudi newspaper Al-Madina on 3 August 1997, he indicated that ‘the real modern planning in Jeddah and other Saudi cities was started in 1958. This was with the co-operation with … the United Nations, which sent Dr. Sayed Karim who later recommended creating the first office for city planning. The first resident expert in this office was Dr. Abdulrahman Makhloof between 1959 and 1963.’

18 These Saudi building regulations were as follows: 1) Prior to the issuance of building permits, confirmation must be made of the existence of concrete posts; 2) Plots are to be sold according to their drawn and established boundaries, and should be strictly prohibited from further subdivision; 3) Height should not exceed eight metres, except with the approval of the concerned authority; 4) A built-up area generally should not exceed sixty percent of the land area, including attachments; 5) Front setbacks should be equal to one-fifth of the width of the road and should not exceed six metres; 6) Side and rear setbacks should not be less than two metres and projections should not be permitted within this area; 7) Building on plots of land specified for utilities and general services should only be permitted for the same purpose; 8) Approval of the plan does not mean confirmation of ownership limits [boundaries] and the municipality should check the legal deed on the actual site; 9) The owner should execute the whole approved plan on the land by putting concrete posts for each plot of land prior to its disposal either by selling or building. See: Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, pp. 205–206; Al-Said, ‘Territorial Behaviour and the Built Environment’, 1992, p. 257.

19 Al-Said, ‘Territorial Behaviour and the Built Environment’, pp. 258–259.

20 Al-Hathloul & Anis-ur-Rahmaam, ‘The Evolution of Urban and Regional Planning in Saudi Arabia’, pp. 208–211. This can be seen from the master-plans that were launched in all regions in Saudi Arabia from 1968–1978, as follows: Western Region by Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners in 1973; Central and Northern regions by Doxiadis and Ekistics, completed in 1975; Eastern Region by Candilis Metra International Consultants (France) in 1975–1976; Southern Region by Kenzo Tange & UTREC in 1977–1978.

21 Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, p. 174.

22 The first relevant regulation, the Municipalities Statute, was issued by the government in 1937 under the Royal Order No. 8723, Rajab 1357H. This order defined the role of the municipality in supervising the city, including construction. This statute was followed by another one called ‘Roads and Building Statute’ in 1941. See: Al-Hathloul & Mohamed Anis-ur-Rahmaam, ‘The Evolution of Urban and Regional Planning in Saudi Arabia’, p. 206.

23 Al-Said, ‘Territorial Behaviour and the Built Environment’, p. 257.

24 Shirreff, ‘Saudi Arabia’, pp. 315–338; A.J. Al-Saati, ‘Housing Finance and Residents’ Satisfaction: The Case of Real Estate Development Fund (REDF)’, Open House International, vol. 1, no. 2 (1989): 33. See also, Tarik M. Al-Soliman, ‘Societal Values and their Effect on the Built Environment in Saudi Arabia: A Recent Account’, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, vol. 8, no. 3 (Autumn 1991): 235–255. The Real Estate Development Fund (REDF) was established in 1975 to provide people with interest-free loans to build new houses. For example, between 1974 and 1987 more than 440,000 new homes were constructed in different Saudi cities as a result of government loans.

25 Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change’, p. 171.

26 Al-Saati, ‘Housing Finance and Resident’s Satisfaction’, pp. 33–41; Saleh Al-Hathloul & Edadan, N., ‘Housing Stock Management Issues in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’, Housing Studies, vol. 7, no. 4 (1992): 268–279; Tawfiq M. Abu-Ghazzeh, ‘Vernacular Architecture Education in the Islamic Society of Saudi Arabia: Towards the Development of an Authentic Contemporary Built Environment’, Habitat International, vol. 21, no. 2 (June 1997): 229–253.

27 Thomas W. Shea, ‘Measuring the Changing Family Consumption Patterns of Aramco’s Saudi Arab Employees – 1962 and 1968’, in Derek Hopwood (ed.), The Arabian Peninsula: Society and Politics (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1972), p. 249.

28 It was commonplace, for instance, for British visitors to talk about the contradictory faces of Riyadh in the 1960’s, with one recalling being told by his Saudi friends: ‘It’s becoming a city of two different worlds’.

29 Yousef M. Fadan, ‘The Development of Contemporary Housing in Saudi Arabia (1950–1983)’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 1983), p. 74.

30 The appearance of such a class, however, conflicted with the egalitarian characteristics of traditional Saudi society, where rich and poor lived closed to each other. This increased the conflict between old and new, and the issue of identity appeared as a social problem, especially with the acceleration towards change in the following years.

31 J.J. Boon, ‘The Modern Saudi Villa: Its Cause and Effect’, American Journal for Science and Engineering, vol. 7, no. 2 (1982): 132–143.

32 Ibid., p. 140.

33 H.S. Jomah, ‘The Traditional Process of Producing a House in Arabia during the 18th and 19th Centuries: A Case of Hedjaz’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 1992), pp. 327–328.

34 Ibid., p. 328.

35 Irwin Altman & Mary Gauvain, ‘A Cross-Cultural and Dialectic Analysis of Homes’, in Lynn S. Liben et al. (eds), Spatial Representation and Behavior A Cross the Life Span: Theory and Application (New York: Academic Press, 1981), pp. 283–320.

36 Ibid., p. 296. The authors state that ‘the uniqueness and identity of a family is often reflected in the construction of individual homes’, and then add that ‘a family’s identity is often symbolized by the number and variety of rooms in its home’.

37 Witold Rybczynski, Home: A Short History of an Idea (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1986), p. 9.

38 Mashary Al-Naim, ‘The Home Environment in Saudi Arabia and Gulf States – (Vol. 1) Growth of Identity Crises and Origin of Identity + (Vol. 2) The Dilemma of Cultural Resistance, Identity in Transition’, CRiSSMA Working Paper no. 7 (Milan: Pubblicazioni dell’I.S.U. Universita Cattolica, 2006).

39 Mashary Al-Naim, ‘Political Influences and Paradigm Shifts in The Contemporary Arab Cities: Questioning the Identity of Urban Form’, CRiSSMA Working Paper no. 7 (Milan: Pubblicazioni dell’I.S.U. Universita Cattolica, 2005).

1 Burj Khalifa in Dubai by SOM Architects (2004–2010)

2 Aerial view of the new blocks and landscaping around the Burj Khalifa in Dubai

3 Ghani Palace Hotel (2002) by Saleh Al Mutawa in Kuwait City

4 National Assembly Building (1978–1982) by Jorn Utzon in Kuwait City

5 General view of the city of Dammam, Saudi Arabia

6 Luxury villa-type dwelling in Dammam, Saudi Arabia

8 Religious festivities in Manama, Bahrain, on the evening of the Day of Ashura