7

Distortions in the Mirror: Segregation, Control and Garden City Ideals at Langa Native Village

To put the matter in an extreme way, the native home is essentially a place of refuge from the weather, from wild beasts, from the observation of possible enemies, and for the fulfilment of those perfectly natural functions of cover and shelter that savour rather of the bird’s nest than of the highly organized and complicated villa which the European considers as essential for his requirements. No sewing rooms, boudoirs, studies, offices, billiard rooms and music salons, or other apartmental concomitants of a complex social life enter into the picture, and the problem being thus reduced to the simplest possible elements is one which should be capable of a simple and satisfactory solution … Simple, however, as the needs may be, there are certain requirements that must be satisfied in every reasonably human habitation, and those requirements are stated as follows:- The need for shelter, warmth, reasonable privacy, the storage of food, attention to hygiene, durability, comfort, and ease of ingress and egress. Most of these requirements are ignored in the ordinary Kaffir hut, but all of them are met singly in varieties which we have had opportunities for seeing and studying upon records. The ordinary hut contains little, if any, means of egress for the smoke of a fire from within, takes no thought for the necessity of food storage, gives a maximum amount of inconvenience in ingress and egress by reason of the smallness of its entrance doorway and the awkwardness of the placing of its roof-props from within, takes no account of sanitation owing to defects in light and air, has no arrangement for privacy, and few, if any, of the requirements incidental to the lowest conceivable standard of human comfort.1

Assessing how and where Natives should live in the city was first answered in 1884 when the colonial government of the Cape of Good Hope implemented the Native Locations Act.2 Locations suggest Native American ‘reservations’ – territories within the state where the cultural life of Natives supposedly continues regardless of the catastrophic upheaval of colonization. Locations were territories through which Empire could contain ‘Africa.’ More to the point, however, the legislation became a line snaking across the land, circling, quarantining and segregating out peripheral areas contaminated by colonialism. The aim of the Act was to rationalize the management and space of locations – particularly those on private land, which had tended to emerge somewhat organically over time. It was precisely because urbanizing black people were being housed in marginal zones surrounding urban areas – on private farms beyond municipal control – that it was enacted. These areas were not tribal territories, though they began to show threatening signs of Native space within White territories, or at its boundary.

In terms of the Act, a location was any area containing dwellings of three or more Native men – ‘Kafirs, Fingoes, Basutos, Hottentots, Bushmen and the like’ – who were not in the employment of the farmer on whose land they were residing. Implicit in the Act was the understanding that single unemployed black men who had moved from tribal protectorates into urbanizing areas were a potential threat that needed to be managed and controlled.

In fact, it went so far as to give the Governor and his agents the power not only to delimit the area to be used for the erection of dwellings on private and public land, but also to limit the number of dwellings allowed in the space, in other words, to plan the very space of the location. Once the licensed location was established, an inspector would be appointed whose duties included keeping a register of the number of dwellings as well as the names and occupations of the inhabitants. This inspector had to be given notice if an inhabitant of the location wanted to erect a new dwelling, presumably to maintain order within the space. The understanding of black urbanites as transient inhabitants of the White city was strong enough to allow a hut in a location that had not been occupied during that calendar year to be destroyed. Although the Act did not restrict the kind of dwellings that could be erected in the location, its concern for containment and the allowance for the planning of the space was one of the first uses of ‘White space’ in the control of Natives. By setting aside the territory, its distinctive Otherness could be managed – psychically, as well as literally.

It is important to realize that the Natives Location Act and its amendment of 1899 did not restrict black people’s ability to purchase land or prevent their access to accommodation within the municipal areas themselves. District Six in Cape Town was an area in which many jobseekers were accommodated as rent-payers. It took the Native Reserve Location Act of 1902 to fundamentally change this.3 This Act gave the Governor power to proclaim specific municipalities as exclusionary zones wherein Natives, with a few exceptions, could no longer reside. This was ostensibly to limit the spread of future outbreaks of bubonic plague which had struck Cape Town in 1901 – even though there had been no evidence that the incidence of the disease was higher in Native areas than in European suburbs.

The corollary of this exclusion of Natives from the space of the city was the need to establish the Reserve Locations in which those employed in the municipal areas were required to live. The Native Reserve Locations Act was the first instance of housing per se as a conceptual responsibility of the State, although this occurred largely through default of the State’s attempts to sanitize the city as a White space. Not only was the Governor allowed to make rules on the provision of dwellings, he could regulate ‘the erection and use of private dwellings, buildings and other structures in the location, and the ventilation, lighting, materials, and manner of construction of all such dwellings, buildings, and other structures.’ Whereas the Native Location Act had considered the containment of Native space in the city through means of boundaries sufficient in the ‘sanitizing’ of the city, the Native Reserve Locations Act went one step further. It anticipated the potential eradication of Native space in the city. Government architects could now define the built environment of the location on their own terms. Finally, the Native Reserve Locations Amendment Act of 1905 allowed Natives to erect their own dwellings on terms and conditions agreed to by the Governor.4 However this affirming possibility of self-built housing was not enacted in any substantial way.

THE VISIBLE PRESENCE OF NATIVES IN THE CITY AND THE MAKING OF NDABENI

Cape Town, unlike the two ‘frontier towns’ of Port Elizabeth and East London, had no immediate local Native population from which to draw unskilled labour and consequently had no history of using ‘locations’ to avoid housing unskilled labour whilst simultaneously maintaining racial segregation through spatial boundaries.

In the minutes of the Commission on a Native Location for Capetown5 in 1900 (hereafter CNL), concern was voiced over the physical presence of ‘the Native’ within the space of the city, which in the view of one of the interlocutors had already been ‘turned into a location.’6 To say as much would be to suggest that the city had become a Native space and was suffering a kind of invasion of Otherness. The idea of a location was approached with much ambivalence during the Commission and even though the idea of what constituted a location was changing, the very word7 was likely to conjure an image of uncontrolled areas of Native dwellings and insanitary conditions as had developed in Port Elizabeth8 and East London9 – rather than the highly controlled social space later associated with it.10

In Cape Town, the Native Locations Act was used to house indentured labourers in barracks at the docks much like the mine compounds in Kimberley and Johannesburg. But by the end of the nineteenth century there was a growing immigrant population of mobile Natives who found accommodation within the space of the city itself. It was a real problem for the agents of Empire and the White middle class in general. Contrary to the English reverence for laissez faire development, free markets and the sanctity of individual liberty, the CNL was established to deal with this ‘invasion’ and maintain the city as a White space. How to resolve the spatial contradiction between the need to house what the Cape Times called ‘a floating population of uncivilized natives’11 near their place of work (largely in the docks, brickfields and in the city itself) while ridding the city of the visible presence of this ‘alien Kafir population,’12 was one of the main thrusts of the CNL. It was actually the arrival of the bubonic plague in February 1901 and the enactment of quarantine laws of the Public Health Act of 1897 that ultimately brought about selected forced segregation in the City, albeit informed and guided by the recommendations of the CNL.13 Nevertheless, the raw verbatim reports of the witnesses and interlocutors at the commission explored below indicate the views of those in power at the time and offer insight into their understanding of race and the production of the city as a White space.

One of the main causes for concern was the extensive spatial distribution of Natives in many dwelling houses throughout the city. The Cape Times quoted statistics from the MOH of some 80 places at which 1,600 Natives were living within the city proper.14 Aside from the lone voice of the City Engineer, the general agreement of those giving evidence was that having Natives distributed throughout the city was an intolerable affair, not only due to the decrease in value of property next to lodging houses,15 but also in terms of limiting the distribution of what Dr E.B. Fuller, the MOH, called ‘Kafir foci’16 and the ‘nuisance’ associated with the dwellers themselves.17 Black people were living in lodging houses established by Missions and Churches such as St. Columba’s Home and St Philip’s Mission, or in the 200-roomed Metropole run by the Salvation Army, and in residences owned by black people in Hortsley Street.

Whatever the precise distribution, the majority found accommodation in the racially and ethnically heterogeneous District One and District Six.18

It was not only the distribution of their dwelling spaces throughout the city that was the governing concern but the unchecked visible presence of black people in public that rattled those in positions of power. In fact, one of the spurs for the CNL had been a ‘tribal fight’ almost a year before within the city itself and had caused much talk of how to get rid of the ‘barbarians,’19 although it should be noted that the establishment of a location was a longstanding consideration of the City Council before this particular event.20 Labourers from rural areas were the main focus of the commission and the attitude of those giving evidence about removing educated or ‘civilized Natives’ was somewhat ambivalent.21 Poorer black people, marked as ‘primitive’ through the combination of skin colour and their ‘tribal’ clothing, were an extreme Other. There was a strong desire to rid the city of ‘raw kafirs.’22 As Dr Jane Waterston observed: ‘Another tremendous mistake seems to me to consist in the natives being allowed to pass through the principal thoroughfares on their way to their work. The men who come down Grave Street every morning are nearly all raw Kafirs, and they make a great noise. Up-country the raw aboriginal Kafir is never under any condition put amongst civilized people or allowed near to houses.’23 There was also concern over Natives ‘walking about (with exception of a blanket) in a perfectly nude condition,’24 whilst the City Engineer admitted receiving complaints of ‘the passing to and fro in the streets of natives.’25

The Mayor of Cape Town, Thomas O’Reilly, wasn’t sold on a Native location for the city since ‘there would be a procession of natives through the streets to and from their work two or three times a day’ suggesting more sporadic, less dense movement was more acceptable. He preferred a location at Maitland so ‘you would be able to take the men direct from there to the Docks and back again,’ presumably by train.26 For the middle class, who were starting to display their identity in the commercial precincts of Adderley and St. George’s Streets, and the pier at the harbour, and the Company Gardens,27 such obvious signs of Otherness would have made their pretences to respectability and Englishness more transparent.

The Commission reached a draft agreement on the 17 October 1900, which set out some basic principles for the new location at the periphery of the city (Figure 7.1).28

Three classes of Natives were defined, namely, ‘the temporary or migratory, the permanent or settled and the educated or superior natives,’ but only two kinds of accommodation were suggested, namely, ‘a few small cottages for some stable natives especially those with families [and] a few larger rooms or barrack rooms for accommodation of migratory natives’. This draft agreement suggests that had the plague not hit Cape Town in 1901, bringing about the rapid removal of Natives to the area that eventually became known as Ndabeni, then the accommodation of Cape Town’s first location would have been more in keeping with European standards than the stripped-down dwellings that were hastily erected. The dwellings were to have been constructed of brick, with a minimum airspace of 400 cu ft per adult – the standard minimum in England. It was, however, not ‘feasible’ to provide gardens (Figure 7.2).

7.1 Map locating Maitland Garden Village, Ndabeni, Pinelands, Langa, and Bokmakirie

Here, then, was the first instance in Cape Town of Empire attempting to classify and differentiate colonial subjects into spatial conditions matching their position on the roster of ‘civilization.’ Socio-spatial types were starting to gain fixity and definition. However, the unbuilt accommodation that the City Engineer had designed for 480 men was suddenly increased to that for 4,000 men with the arrival of the plague.29 Lewis Mansergh, as Secretary of the Public Works Department, even allowed, in the emergency conditions, 12 families to erect wattle huts, contravening the draft agreement of the CNL that had explicitly intended to exclude Natives from building their own homes.30 Furthermore, the floors of some dwellings were constructed of mud.31

A few months after Ndabeni was hurriedly put together, efforts were made to make the environment more attractive and differentiated, with churches, a hospital, and a recreation hall planned. The ambivalence with which Ndabeni was approached comes through in the provision of the recreation hall, with Mansergh suggesting that the ‘design already framed might be slightly altered from its present severity of outline in order to make the Hall somewhat more of a feature in the Location.’32 The clerk of works suggested a year later that ‘a market place should be established with stalls erected something similar to those used on the market places in English Country Towns.’33 The Public Works Department was even intent on building some ‘model cottages’ in 1902.34 These are important observations; they suggest that even before Garden City ideas came to dominate Cape Town’s housing concerns, there was an impulse on the part of the administrators of the city to fashion an environment they were familiar with, one which may have come to pass were it not for the plague of 1901. They illustrate the tension Empire manifests for its administrators: unsettling recognition of the inadequacy of its housing projects in relation to the richness of the motherland ‘model’ and the mismatch of that model in relation to Other subjects. The anxiety is present in how Mansergh fussed over decoration in an attempt to overcome the severity of the architecture being manifested.

7.2 Ndabeni, ‘Better Class Houses’ 30 September 1902

7.3 Ndabeni Native Location ‘CT Black People 2 and 3,’ date unknown

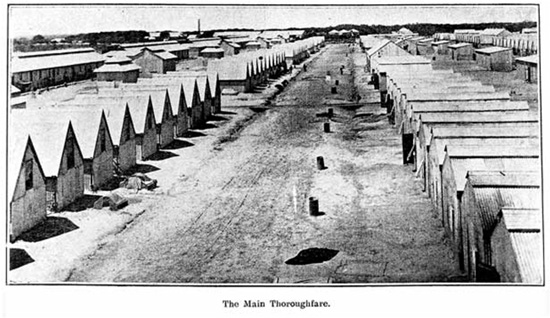

Ultimately, though, Ndabeni resembled the architecture of the concentration and military camps of the South African War (Figures 7.3–7.4). Furthermore, the seven-inch numbers35 attached to the dwellings were a sign, not for postal services, but for the more efficient management and control of an urban workforce, and an index that routed Natives back to a magisterial district in the tribal areas from where they came. The Acting Superintendent of Natives at Ndabeni, W. Power Leary suggested:

That the huts be numbered in blocks of 25 huts each, less or more according to situation, thus – A1/M and so on; even numbers on the one side, and odd numbers on the other. Each man registered has his hut number in the register, and particulars relating to his home address. The ‘M’ under ‘A/1’ indicates a Municipal hut. The above particulars are also entered on the identification card given to each individual on registration.36

Consequently, Ndabeni did not enact planned or imagined social hierarchies of ‘civilized Natives’ in ‘cottages’ versus tradition-oriented migrant labourers in compounds. The constant removal of signs of Otherness – such as wattle-and-daub wind screens – as well as the relentless rigour of Ndabeni’s layout suggest it was, even at its initiation, considered a potentially problematic Native space that had to be ordered and managed because of its proximity to ‘civilization.’ The later establishment of temporary round huts or tents to the east of the settlement points to the ambivalence of the conception of the location; here Ndabeni is both a ‘location’ or Native space as well as a highly-ordered and regularized White space. The circle as the ‘archetypal’ signifier of ‘Africa’ ironically returns here, but proclaims the territory as a neutered Native space and its inhabitants temporary visitors to the city from another place.

7.4 Ndabeni, layout 1902 (left) and aerial photograph, 1926 (right).

GOING ROUND IN CIRCLES OR SQUARES: HOW TO HOUSE ‘THE NATIVE’

The 1914 report of the Tuberculosis Commission was one of the first major investigations into the way people lived in different parts of the country, signalling the beginnings of a comprehensive mapping of the lived domestic space of South Africa. The report tends to idealize the life of rural Natives and their relationship to their dwellings which is not to say that the Commission did not find aspects of Native dwellings problematic. Nevertheless, it has many such rosily patronizing descriptions: ‘The raw native in his kraal lives in the main an easy, healthy open-air life. Much time is passed idling in the sun. The hut is usually occupied only at night and when shelter from the weather is required.’37 Although they were concerned about the perceived lack of ventilation and the comparatively large amounts of dust from dirt floors and their possible effects on the health of lungs, the Commission found that there was generally a healthy symbiosis between Native, dwelling and environment. Ideally then, Native space could be located adjacent to the city: ‘If means could be devised by which native women could resort to the labour centres in proportionate numbers to the men, and when there live without deterioration, as native families and under native conditions, it would be an advantage, as well on health grounds as for other reasons.’38 These ‘other reasons’ would have included savings to the local municipalities spared having to invest in housing per se. Yet this cut-and-paste of different worlds suggests an even stronger desire for homeostasis, of retaining the static, unthreatening, and distant world of rural Natives – a key and failed ambition of apartheid’s future ‘homeland’ project. Colonial society felt least threatened by the Other in the figure of extreme Other. It was when the Native began to resemble the colonial master –Homi Bhabha’s ‘mimic man’39 – that the tenuous construct of the Self was under pressure in the uncomfortable recognition of the reflective proximity of the Other to Self. To have a White city and a native village side-by-side, their boundaries clearly demarcated, would have been the ideal ‘solution’ to one of the undesired ‘side-effects’ of colonialism.

Yet the reforming impulses of the English presented them with a paradox of their own making. There had been a longstanding desire on the part of missionaries to remove the circle as a structuring device from Native dwellings and buildings, as a way of continuing the ‘civilizing’ mission – the instrumentalist programme par excellence.40 The Natal government had even offered tax incentives to those Natives who lived in orthogonal dwellings filled with Western furniture.41

Both these moves were part of an attempt to inculcate Western values, especially privacy and individuality, through the compartmentalization of use-spaces in specifically orthogonal rooms. It is clear that those writing the Tuberculosis Commission report in 1914 were happy to promote the development of dwellings with multiple separate spaces as typified in the recent growth of orthogonal homes, largely as this would give ‘greater space and privacy to the individual occupants.’42

Yet they also presented these dwellings as problematic, incomplete places of either the Self or the Other. It was particularly in the use of space that the mismatch was exposed. The Report identified dirt as the main problem: ‘For the square hut is generally much dirtier, its corners do not get cleaned out, its windows are frequently closed up, the materials of which it is constructed are less pervious to natural ventilation, and European furniture more often than not means the collecting of all sorts of rubbish of not the slightest utility, which is never shifted and is the harbourer of dirt.’43 A condition in-between that of the ‘pure’ Native dwelling and the ‘desired’ detached Western dwelling, was basically intolerable. Not only was this in-betweeness considered dangerous, in its social and health dimensions, for the potential ‘damage’ to Natives in this colonial dystopia, but also because such hybridity pointed, in a psychological sense, to the potential breakdown of the Self. In other words, the hybrid hut made a mockery of the niceties and foibles of standards and practices dear to the agents of Empire, the aesthetics of cleanliness and utility. The Other needed to be maintained in a simulacra of the Self and that simulacra of the Self would later appear in the form of a supremely socializing housing phenomenon, the Garden City Movement.

The example of the Tuberculosis Commission is not to suggest that the structural unity of the Native and his dwelling was thoroughly and consistently idealized. The Comaroffs have shown, through an analysis of earlier colonial times in South Africa44 that the dominant idea in missionary representations was that Natives and the Native hut were part of the natural world and consequently lacked cultural sophistication to mark their being human. To understand the depth of this sentiment it is worth exploring two quotes. The first, from an Architect, Builder & Engineer article titled ‘Native Housing. Physical and Social Conditions’ (at the beginning of this chapter) partly concerns the Native hut in its rural setting. Here the representation of Native dwellings allows the reader to associate Natives with the natural or animal world, if not animals themselves. Not only is ‘the Native home’ seen to lack cultural sophistication, it lacks characteristics and qualities basic and necessary to any human dwelling. It should be noted that this article was published right at the time Cape Town’s new Native location of Langa was being imagined and could therefore be read as part of the process in the legitimizing of the building of simple dwellings for Natives based on their ‘naturally lesser’ needs. Clearly the complexities of African urban settlement were lost on a conventional architectural discourse used to appraise a home through its single family inhabitants and vice versa; other kinds of cultural practices get blurred in such a focused lens. The Native’s hut was a ‘bird’s nest’ and part of the natural world. A phrase like ‘every reasonably human habitation’ and the list of defining requirements suggests that both the hut and the Native are not part of the human world at all. These associational qualities also reinforced the notion that Natives were animal-like and of the ‘natural’ world. That being so, they had no legitimate right to the sophisticated cosmopolitan space of the city.

This article was also written when debate was raging on the soon to be passed Native (Urban Areas) Act – an Act that effectively limited black peoples’ access to South Africa’s cities through registration, work passes, and residential segregation.

Consider the second example of the rural dwelling used as an associational device defining the identity of Natives as Other: ‘The native likes everything in circles: they think in circles. After all, this is the type of hut that you find universally all over South Africa. It is as natural for a native to live in a round hut as a snake to live in a hole.’45 This from a paper read at the Thirteenth Session of the Association of Municipal Corporations of the Cape Province, held at Grahamstown, from 10 to 12 May 1920, and deals explicitly with the Bill leading to the The Native (Urban Areas) Act (NUAA) and municipalities’ responsibilities in providing housing for Natives and controlling their presence in the city. This paper seems to have been largely based on the findings of the Tuberculosis Commission, especially the ambivalence as regards the use of circular dwellings for housing Natives in urban areas. The rhetorical devices persist, principally through the simile associating Natives with the animal world, and a dangerous and threatening one at that. Here the circular space and form of the Native dwelling is also used to define Natives as fundamentally irrational, pointing to a need for guidance. The Native, defined through his ‘natural’ dwelling, is unsophisticated, animal-like, threatening and clearly lacking any claim or right to the city whilst ‘belonging’ to the rural landscape. For a Native to live in the city at all it would have to be on European terms under highly controlled conditions.

This notion of the Native as essentially rural and a peasant is one of the main sentiments expressed at the time the NUAA was debated.46

THE NATIVE (URBAN AREAS) ACT OF 1923

The Native (Urban Areas) Act of 192347 brought about a nation-wide policy similar to that of the Native Reserve Locations Act through which Ndabeni had been realized – although the related Stallard Commission leading to the Act had proposed that all Natives were ultimately to be considered as rural people required to return to the Reserves if and when their labour was no longer needed in the cities. In an infamous comment in the report of the Commission, the understanding of the city as a White space could not be more clearly voiced. Not only were the ‘habitually unemployed’ to be removed but anyone not a model citizen was in perpetual danger of what effectively amounted to deportation to the reservations, that is to say: ‘he be removed from the urban area or proclaimed area as the case may be and sent to the place to which he belongs’ [emphasis added]. Urban Natives were a spatial anomaly best resolved through their temporary residence in, or leasing of, a White space wherein the visible signs of their Otherness might be erased. Indeed, the Natives Land Act of 1913 had effectively removed the possibility of any Native purchasing land outside of areas that were essentially tribal reserves or pre-existing locations such as Ndabeni, although it was still possible for a Native to purchase property within the boundaries of a municipality or local authority.48 The Cape, having a longer history of land ownership by those other than European, was excluded from this limitation by allowing anyone wealthy enough to be on the voters’ role free access to purchase any property. In a move designed to remove this disordering presence of Natives within the White space of the city, the NUAA offered municipalities the option to opt into the Act and to declare themselves as territories where no Native could purchase land.

In contrast to the Native Reserve Locations Act which had placed the onus of housing on the State, the NUAA made the housing and management of Natives in locations the responsibility of local authorities in whose boundaries the locations had been established. Whilst the design and supply of housing was the charge of the local authority, there was opportunity for Natives to erect their own dwellings, the design, dimensions and materials of which were subject to the approval of the local authority based on any rules and regulations it had passed in this regard. Rather than being driven by a consideration of individual desires for self-determination, this clause was included in the hope that the cost of dwellings could be reduced through owner-built labour. The Act did, in a similar manner, allow for a number of institutions such as ‘banks, hospitals, dispensaries, maternity homes, lodging houses, baths, wash-houses, recreation buildings or grounds, eating houses’ to be developed in the locations. However, the paternalist impulse still sought to control, as expressed in the sentiment that these must be ‘deemed by the urban local authority to be necessary or advisable in the interests of natives.’ Ultimately though, the elements of design were at the approval of the Minister of Native Affairs, including the ‘suitability of area and situation of the land set apart and the title thereto, the general plan and layout of the location or native village, the situation, nature and dimensions of any building and the provision made for water, lighting, sanitary and other necessary services for the location, native village or hostel as the case may be.’ The location was an un-negotiable space where hybrid spatial possibilities were policed.

The un-negotiated and un-negotiable space of the location was in many ways the expression of Whiteness working at resolving the contradictions of race and exploitation in the colonial context. Its inhabitants, understood to be transients, were disallowed a vested interest in the specifics of the place. The location, as a smaller, bounded version of the White space of the city could remain undisrupted and unmarked by the passing of black bodies within its regularized and regulated space with all the opportunity for the reverse to occur. Finally, in order to reinforce the potential of social control through spatial means, the NUAA made it illegal for any Native to dwell within three miles of a local authority’s boundary except within the location and unless specifically employed by the person on whose land the Native was dwelling. This three mile exclusion zone effectively twisted ‘Africa’ outside and beyond the frame of reference of the administrators of the city, providing welcome psychic relief that this ordering strategy provided.

DISTORTIONS IN THE MIRROR: GARDEN CITY IDEALS AT LANGA NATIVE VILLAGE

If Wells Square had pressured the City into providing segregated housing for its employees, the passing of the NUAA also put the onus of providing accommodation for the Native residents of the city in the hands of the Council. That the Council had long avoided taking over the management of Ndabeni49 suggests how strong the general sentiment was that ‘the Native Problem’ was to be dealt with by the Central Government who had always regulated the labour supply from the tribal areas. In fact, even though Ndabeni was within the borders of the City, it was legally separate, and as a Government reserve was exempt from legislation such as the NUAA.

Ndabeni was only incorporated into Cape Town under the NUAA on 1 April 192650 since the registering and control of Natives in the city, through their allocation in space that this Act facilitated, would have been rendered inoperable had Ndabeni remained as a Government reserve. Thus, the question of how and where people should live fell squarely on the City Council and its various committees who had already started to develop state-funded housing projects through Maitland Garden Village and the Roeland Street scheme.

To deal with the need to establish a new location, the Council constituted the Natives Township Committee in 1922, which a little while later became the Native Affairs Committee (hereafter NAC). The importance of the work at hand was indicated by the presence of the various mayors of Cape Town at its meetings who were also often enough members when not holding that office. Right from its first meeting in November 1922, the Committee considered the location as a ‘township,’51 in other words, a new residential development of Cape Town rather than a space of the Other which the term ‘location’ tended to signify. The fact that the township was to be developed with loans supported by the ratepayers under the Municipal Provision of Homes Ordinance potentially put it on the same standing as Maitland Garden Village. The NUAA had allowed for the provision of a ‘location’ or a ‘native village,’ the latter signifying the ability for natives to become homeowners on land leased from the local authority. Contrary to what may be understood by the term today, ‘native village’ denoted a sense of an English village rather than a rural African village and was part of the common discourse that had developed around the idea of the Garden City Movement in Cape Town at the time.

7.5 Pinelands Garden City, Cape Dutch revival cottage, at Links Drive and South Way

In the parliamentary debate on the draft bill General Smuts argued that the ‘native villages’ were intended for those ‘natives who are no longer of a semi-barbarous type and who have been taught and developed, and their housing conditions must necessarily be of a different character.’52 As will be seen, the initial township layout by A.J. Thompson certainly supports this. In the NAC’s advert for the Superintendent of Natives of the proposed Native township, Langa is called ‘Langaville’ and the Superintendent would be required to advise the Committee in the laying out of the ‘Village.’53

At the suggestion of the City Engineer, T.B. Lloyd Davies, the Council engaged the English architect Albert John Thompson who had successfully completed the design of the adjacent Pinelands Garden City, to prepare the layout for the township of 5,000 residents, capable of expanding to allow for 10,000.54 Thompson, who as early as 1921 had been lecturing members of the Cape Institute of Architects (CIoA) including Delbridge, Glennie, Ritchie Fallon and John Perry on his work in England, had been used by the Pinelands Garden City Trust at the recommendation of Raymond Unwin to rationalize John Perry’s winning design for Pinelands layout and oversee the submittals of plans. Pinelands, with its Arts and Crafts cottages as exemplars of Englishness, quickly became reserved for Whites only (Figure 7.5).

The accommodation for 5,000 residents at Langa was intended to cover the number of residents at Ndabeni that needed to be catered for so that Ndabeni could be closed down. However, following discussion the NAC and consideration of a police report suggesting that as many as 5,000 Natives were resident in the city, the numbers were upped to 8,000 for the first phase and 12,000 for the total. The township was also to include administrative quarters, a hospital, a school, a police station, shops, and staff cottages. In keeping with Garden City ideals, Langa was to be located some eight kilometres from the city centre in the State-owned pine forest of Uitvlugt.

The ambition was to save the working classes from the easily accessible temptations of the city doubled with the desire to remove Natives from White space.

There is scant evidence to suggest that the architect involved in the design and planning of Langa was motivated by any directly racist ideologies, yet there was much to suggest intended social ordering and exclusion. Thompson had worked in Unwin & Parker’s office through the duration of the Letchworth and Hampstead Garden Suburb projects55 in the UK and had gone on to design Swanpool Garden Suburb in Lincoln with Hennel and James. Working under Unwin on the Hampstead Garden Suburb suggests that he approached the ‘Garden Suburb’ as a social machine in which Arts and Crafts aesthetics and relatively low housing densities was to have an uplifting affect on the ‘class’ of person it was designed for. From the very beginning, Langa was conceived programmatically as a place divided between those who were understood to be permanent married residents of Cape Town and those who were single, the latter social status further differentiated between men and women. Thus the residential requirements were considered to be 500 cottages, one hostel for 2,000 single men and one hostel for 100 single women. Thompson, who had been contracted on 27 April 1923, submitted his initial report and layout to the NAC on the 28 June 1923 (Figure 7.6).56

The only layout drawing remaining from that initial design is a drainage-plan overlay using the basic layout plan underneath. The primary structuring device Thompson used in the layout of the township was to locate the main roads, east-west and north-south, on the line of the existing fire-paths that ran through the forest, the reason being to retain ‘some of the very fine trees which are already existing on the lines of these proposed roads.’ The railway line was to be pushed to the boundary of the township so that no traffic – except that for the hospital – would be required to cross it. The train station and the eating hall of one hostel formed the main axial terminations for Station Avenue running north-south, whilst the other hostel’s eating hall formed a minor axial termination for Central Avenue running east-west and crossing Station Avenue at Central Square. Central Square was the intended location of the administration and police quarters, as well as a cinema and two churches – a sort of church and state power-bloc. On the other hand, the station and its square was to form the commercial centre of the scheme, with fish and meat market halls, and fruit and vegetable market halls flanking Station Avenue, and rows of shops flanking the station. The women’s hostel was to be located opposite the school, and a pool was to be built at the southwest corner of the scheme, mainly to assist in controlling water run-off at the site’s lowest point. These points aside, it seems clear – from Thompson’s concern for placing the school away from the traffic of the main roads together with his concern for trees and his leaving open play areas behind the cottages through Unwin-style road layouts – that he was basing the design of Langa on Garden City ideas. The 1,920 houses dotted around the scheme – 8.5 to the net acre as he pointed out – are of a density characteristic of the emerging Garden Suburbs in England and were indicative of the extent to which the township may have been developed in the future. Each plot size was to be standard suburban sizes of 50’ × 100’.

7.6 Langa layout, from Drainage plan, 1923. Key: A. School, B. Meat market, C. Fruit and vegetable market, D. Compound for 200 single women, E. Churches, F. Picture theatre, G. Police station, H. Admin, K. Compound for 2,000 single men, L. Church house. Notes by the author

It seems fairly apparent that Thompson used basic Garden Suburb principles he’d learnt as Unwin’s ‘protégé’ and ‘office manager’57 in his initial and subsequent layout designs of Langa. This is suggested by comparisons made between the Langa layout and the Hampstead Garden Suburb (Figure 7.7) in London along with the First World War munitions townships of Gretna/Eastriggs (Figure 7.8) outside Carlisle and confirmed in his layout of Pinelands (Figure 7.9). These four layout designs share a similar, and somewhat formal and orthogonal, civic and commercial axis typical of Unwin’s ordered-picturesque – although Langa exhibits a far more symmetrical design. All four have a main square designated Central Square, whilst Gretna, Pinelands and Langa have avenues extending from this called Central Avenue – although this name did not remain in use at Langa nor at Eastriggs whose roads where tellingly named as a roll-call of the major cities of the Dominions of the British Empire. Hampstead, Pinelands and Langa have cul-de-sacs as well as communal areas behind the dwellings forming internal squares, although in Pinelands these were largely subsumed by cul-de-sacs. Furthermore, both Pinelands and Langa show the development of a women’s hostel ‘protected’ from the street in a quadrangle form behind a row of houses. For its part Pinelands shows a remarkable similarity to Hampstead in its disposition of the buildings in and around the Central Square. And whilst Hampstead and Pinelands have a far more ‘organic’ and web-like layout, both Gretna/Eastriggs and Langa show a fairly rigid disposition of dwelling accommodation, suggesting their common status as labour centres rather than fully-fledged Garden Suburbs. As we shall see there is a lot to suggest that Thompson used the lessons learnt at Gretna/Eastriggs in his design for Langa despite the fact that he served as an officer for the duration of World War One and would not have worked on the design in Unwin’s office; the concluding compromise of Langa bares remarkable similarities to the more austere cottages of Gretna/Eastriggs. It was also not insignificant that the City Engineer referred to the dwellings in Thompson’s original layout as ‘cottages.’58

7.7 Hampstead Garden Suburb interim layout

At Langa there were telltale elements of the design that, in this dislocating condition of Empire, revealed the more totalitarian tendencies that normally lay hidden behind the bucolic Arts and Crafts architecture of the Garden City Movement. The tendencies to control and segregate embedded within the model sprang to the fore as Thompson easily morphed the master plan to accommodate the ambitions contained in the newly-passed NUAA. The Police Station was specifically located to give ‘efficient police control,’ whereby, Thompson noted

7.8 Raymond Unwin – Layout of Gretna and Eastriggs munitions supply townships, c.1917

7.9 A.J. Thompson – Pinelands, layout of initial development, 1920

A man on duty at the tower will be able to see over the whole Estate, and again a man on point duty at the centre of what you might call the Central Square will be able to see not only from end to end of the Central Avenue, but will be able to look into each of the large Compounds and directly up to the Station Square, and a Police Patrol on the roads running North and South would get immediate view East and West down all the other roads and across the open spaces.59

Furthermore, Thompson suggested that his ‘compounds’ were modelled on those on the Crown Mines in Johannesburg (although the 27’ × 30’ unit was intended to accommodate 25 men and not 40 as in Johannesburg) – it should be noted that ‘hostel,’ rather than ‘compound,’ was the standard form of group housing in the typical Garden Suburb.

Although the City Engineer had been given complete control of the development of Langa until a Superintendent of Natives – a paternalist position of mediation and control akin to the status of a White ‘chief’ – could be selected,60 he specifically requested that Thompson be retained as ‘Consulting Architect’ on the project for a year.61 Thompson was commissioned to design inter alia: a meat market, a fruit and vegetable market, a hostel for 200 single women, two hostels each for 2,000 single men, a Police station, administration offices, administration quarters, and cottages for married natives and their families. Together they set about interpreting the comments from the Provincial Secretary reporting suggestions made by Colonel Trew, Deputy Commissioner of Police, and Dr Wilmot, Assistant Medical Officer of Health for the Union of South Africa. These included:

7.10 Langa layout, c.1926

2). A Compound should not hold more than 1,000 natives and should be so designed that not more than 250 men should occupy one section and further that the sections be so planned that in case of emergency each can be closed to access from any other section. 3). The Compounds should be so placed that they are in the vicinity of the railway station so as to avoid passage through the area set apart for married natives. 4). The Compounds should be surrounded by an open space. It is considered that the suggestion No.3 would be in the interests of morality and all would greatly facilitate police control.62

That the compound was considered to be a space apart – without the Romantic pretences of Hampstead Garden Suburb and its ‘medieval’ wall – is confirmed by the quote above and revealed in the resulting design in which the suggestions of Trew and Wilmot were taken into account in the star-shaped compound indicated (Figure 7.10). Single males were further classified and ordered into appropriate accommodation; migrant labourers considered most likely to return to tribal areas after contract labour ended would occupy the Compounds (or barracks as they were now being called), and those resident in the city a fairly long time and not considered ‘temporaries’ were housed on the ‘cubicle system’ or ‘Quarters’ for more ‘comfort and privacy.’63 The second layout design shows the compound at the west end of what became Washington Street replaced by these ‘Quarters’ with ablution facilities located between the units. While the permanent, single men of the city may have preferred these single room dwellings64 and could have afforded the higher rents intended, the basic urge to keep migrant labourers separate from permanently urbanized Natives for fear of mutual social and moral ‘contamination’ plays itself out in the interim and final design. Whilst Hampstead and Letchworth had largely failed at bringing different classes together in areas of common interest, the design at Langa – true to the hardening taxonomies of race and class in Imperial Cape Town – shows a clear intention of ‘class’ segregation. Open interaction was spatially consigned to the communal kitchen and dining area now at the centre of the ‘barracks’.

As for the compound, Thompson stated, in a report dated 20 November 1923, ‘we should endeavour to make it look as little like a barracks as possible.’65 Control of the ‘inmates’ was, however, a major concern. The barracks (‘compound’ seems more appropriate to the overall fenced-in space of Langa itself) were divided into four 250 person ‘wings’ (shown as large U’s on the layout, and perhaps similar to Garden City quadrangle accommodation) to better isolate potential unrest. The design essentially had the U’s turn their backs on the outside world, setting up a series of contained courtyards focused in on the kitchen, eating house and ablution blocks. The revised design, although having no central guard-tower, does resemble the general radial patterns of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century prisons based on the panopticon66 system of surveillance, and is a distinct move away from the initial quadrangle design similar to the hostels of Hampstead and other Garden Suburbs. Certainly the main axial entrance to the barracks was between the admin building and the Superintendent’s house, as well as between two of his assistants’ houses, allowing visual control over who entered and left the barracks (Figure 7.11). The City Engineer even made plans to provide ‘powerful “arc” lamps’ in the spaces around the compound for added surveillance.67

Following what Jennifer Robinson has noted as the emergence of a ‘location strategy,’68 the space of locations in general was overlaid with a complementary set of regulations and rules. As proposed by the Native Affairs Department these included: needing permission to be out the ‘depot’ between 9pm and 4am and only being able to enter or leave ‘the depot except by regular entrances or exits.’69 Natives were not to create disturbances, be intoxicated, misuse latrines or commit ‘indecent acts’ and ‘Every inmate shall keep his clothes, effects and person clean and shall if required by the superintendent or matron submit to such measures for the cleansing of himself and his clothing and effects as the superintendent or matron may deem necessary.’ Cook, as the Superintendent of Natives for Langa proposed these regulations, amongst many others:

7.11 Langa layout, aerial photograph, 1935

11. The register shall set out the name, race and occupation of every registered occupier, and the name, sex and age of each member of his family, and shall specify the dwelling or dwelling place of or in which he or she resides. 15. The Superintendent shall number each dwelling or dwelling place, and shall, for the purpose, be provided by the Council with proper tin-plates, bearing the number of the dwelling or dwelling place legibly painted thereon in large figures. 21. Every occupier of a dwelling or dwelling place shall keep the dwellings and places allotted to him or her in a clean condition. 23. No outhouse, shed, fence or structure shall be erected on or around any dwelling, unless the written permission of the Superintendent shall first have been obtained; and such permission shall only be given if the Superintendent is satisfied that it is necessary. 35. No person, other than an occupier of a dwelling or dwelling place, his wife and family and members under 18 years of age, or married daughters, shall be in the Native Township between the hours of 9p.m. and sunrise, unless he can shew that his presence in the Township is for good and sufficient reasons. 36. No dance, tea-party or entertainment shall be given without the written permission of the Superintendent. 39. The Superintendent or any official of the Native Township Staff shall at all times have access to all buildings of part thereof within the Township, for the purpose of inspection, and no person shall at any time obstruct him or them from such inspection; or refuse or interfere with such access aforesaid.70

That the administrators of these rules were located so close to their subjects was clearly part of this strategy of control. That their dwellings were fairly large and had tiled roofs compared to the corrugated roofs of the other dwellings would have set them further apart. Although the six foot high barbed-wire topped fence that was designed71 to enclose Langa was initially required as part of the conditions by which the central government had granted the city the land in order to ‘protect’ the adjacent forest,72 it no doubt served the obvious added purpose of forcing people to enter and leave Langa via a single point. The detail design of the barracks also contributed to this attempt at control. Thompson pointed out that the windows at the back walls of the barracks were all fixed-panes so that ‘parcels could not be passed through from the outside of the compound’ (Figure 7.12).73 This was a nod to the temperance sensibilities prevalent at the time as well as the restrictions on the type of alcohol Natives could legally consume.

7.12 Langa compound details c.1924

The fixing shut of the windows of the barracks brings to light another aspect of the design for Langa. As a further indication of the locations’ Otherness, and following the NUAA, the space of locations was exempt from Municipal building regulations, although the more ‘scientific’ aspects of dwelling inhabitation were implemented through the Public Health Act, albeit in a less stringent form. Consequently, and in keeping with the emerging ‘science’ of inhabitation introduced into the building regulations, a ridge vent and vent grilles in the walls had to be included to maintain the ‘correct’ air circulation. This requirement also had an influence on the design of the Quarters for single men and women (Figure 7.13). The original sketch design by Thompson shows a hand-written acknowledgement that the design was illegitimate as it was ‘back to back’ and the ceiling was potentially too low at 8’ 6”.74 The dwelling type was eventually built without ceilings with dividing walls that didn’t extend to the roof thereby facilitating cross-ventilation. The obsession over fresh-air as a preventative measure against disease and ill-health – not forgetting the addition of ‘sleeping verandahs’ in middle-class house designs of the period – made the barracks and Quarters very draughty, such that it became a major cause for complaint by the inhabitants.75 Residents of the barracks also complained that the central fireplace in each unit caused the rooms to be filled with smoke even though they had chimneys. Locating the fireplace in the centre of the room obviously gave greater heating efficiency but this may really have been an intentional reference to the central fireplace of the rural ‘hut.’ Other reasons for complaint were the concrete bunks.

7.13 Langa, compound of single huts for men, c.1924

Initially, 725 dwellings for married Natives were to be built by the residents themselves, following the designs and example of two model cottages suggested by G.P. Cook, the Superintendent for Langa.76 Cook, who was Superintendent of the location at Bloemfontein, felt that this approach had been used to good effect there. Qualifying for the married quarters, however, was onerous. Cook recommended that the husband – female heads of households and widows could not apply – would have to prove being resident in Cape Town for a number of years as well as be of a ‘good character’ and ‘legally married otherwise there would be a danger of the wrong class getting a hold of stands.’77 It is important to note that this social management strategy parallels similar tendencies developed by Octavia Hill in England and applied in South Africa.78 Eventually, Cook recommended that the Self-built cottages be abandoned in favour of cottages provided by the Council to facilitate the managed removal of residents from Ndabeni to Langa, a process the ad hoc self-built approach would have prevented.79

7.14 Eastriggs, temporary huts

Although Thompson’s scheme had initially shown detached single-family units, the dwellings that were eventually built were grouped into 6 units of 2 rooms each, 150 of them being handed over for occupation towards the end of 192880 and 300 having been completed by August 1929.81 That Langa was to receive no subsidy82 from the government effected this cost saving strategy, although their disposition and basic and rudimentary spatial arrangement did bare a remarkable similarity to the temporary cottages Unwin designed at Eastriggs which might have been their legitimating precedent (Figure 7.14). Three elements of this change in design and product suggest the piecemeal abandonment of the idea of Langa as a Garden Suburb on lines similar to Maitland Garden Village and Roeland Street: firstly, the maximum grouping of dwelling units as at Roeland Street was four and not six; secondly, most Garden Suburb dwellings for the working classes were at least three-roomed and not the two-roomed dwellings that were built; thirdly, the plans themselves show the two rooms vaguely labelled as ‘room’ as if the interior space was impossible to define through any ‘standard’ functions of the home (Figure 7.15).83

This whittling-away of Garden Suburb standards is also reflected in the way Langa changed its official and colloquial title from Township or Village to Location over the years. It signifies the changes in perception of the reality that the NAC and the City Engineer had created through various economic compromises. Yet the design, as it developed, did not lose all of its Garden Suburb sentiments or values. The Postal Authorities suggested that the proposed post-office and savings bank be located in the station building as this was the ‘business quarter.’84 The City Engineer and the NAC, responding to the Railways Department, even opposed wood-and-iron dwellings for the station:

Read memorandum from the City Engineer dated 6th October, 1923, stating that in his opinion wood-and-iron buildings would not be in keeping with the scheme the Council were about to undertake and further stating that permanent buildings with ample accommodation should be provided, and that the plans of the station and buildings connected therewith should be submitted for the approval of the Committee before construction was commenced.85

All the buildings at Langa were indeed built of brick.

The first few years of Langa’s development saw the city having to manage the location of Ndabeni while removing residents to Langa. In fact, prior to the married quarters becoming available, the accommodation at Ndabeni had to be increased with the introduction of Nissen tents as mentioned earlier.86 The establishment and development of Langa had been urged in 1924 by A.G. Godley, the Secretary of Native Affairs, as the only way for the ‘Council to achieve any measure of success in cleaning up the City.’87 The first ten years saw a significant amount of ongoing building at Langa, yet, and as Saunders notes,88 the City was plagued by the general avoidance of living at Langa and consequently large parts of it remained empty. This had a lot to do with the contradiction between the labour requirements of industrial capitalism and the desires of the agents of Empire to secure the city as a place of Whiteness. Many employers used the allowances in the NUAA to apply to establish mini-locations at the point of employment, pock-marking the city with blackness. Cook, as the Superintendent of Natives for Cape Town, received many applications from dairies and brickfields in this regard as the deputation from the Cape Dairymen’s Association pleaded:

It is an acknowledged fact that natives will stay with one employer – with short holidays to Kaffirland – for years and this is proof that they are, even now, reasonably treated. These boys are the better class of Kaffirs – untainted by civilisation – who come from King Williams Town and the Transkei, and we as Dairymen, feel it incumbent on us to look after their welfare – and return them to their kraals as they were when they came to us.89

7.15 Langa, details of two-roomed blocks, 1932

Many such applications were denied but those that were approved, becoming mini-locations within the White space of the city, were especially surveyed by the MOH. There were some who managed to remain beyond the fences of Langa and the controlling influence of its administrators: domestic workers resided in the suburbs as live-in servants, whilst a few Natives avoided Langa as property owners on the voters roll, although even then Cook was keen to have their living conditions investigated.90

Mostly, the avoidance of residing in Langa was based on its unaffordable rents as the Langa residents’ Natives Advisory Board conveyed in a protest meeting with the Natives Advisory Committee.91 High rents to cover the cost of Langa was a point of contention for the administrators of the city. As the State’s Secretary for Native Affairs, J.F. Herbst noted in a report in 1927 on the problems at Langa, the accommodation was ‘probably more than the temporary native resident needs, and the rental is certainly more than he can afford to pay.’92 He did, however, acknowledge the importance that Langa presented to ‘civilized Natives:’

This has had a very beneficial effect in convincing the natives that the European public is interested in their well-being. The non-native sections of the community need to be reminded that N’dabeni Location and Langa Native Village are of as much concern to natives as are other parts of the City to them. If natives are to have their separate residential area it should be really their home [original emphasis] with all the freedom and liberty which that word connotes.

But Langa certainly did not constitute a home to its residents. Again, in October 1927 the Natives Advisory Board met with the NAC to discuss the problems of Langa.93 Concerns included being forced to eat food prepared in the central kitchens and the lavatories and latrines being ‘out of keeping with the habits of the native people.’ The fact that the police could enter the accommodation at Langa without a search warrant was noted. The biggest problem, however, was the draughtiness of both the Quarters and the rooms of the barracks. The Rev. Mtimkulu noted:

Langa was supposed to be a model township, but the heathen man did not understand the ventilation of the barracks, and to train him by force was to ask him to run wild. The wall partitions should be raised to roof height. If the suggestions he had outlined were given effect to, the hearts of the native people would be won, and Langa would be full in a few weeks time.

No action was taken to ameliorate these conditions.

In fact the Town Clerk had met with the Secretary for Justice and the Deputy Commissioner for Police a few days before in order to legalize the appointment of special City-employed constables whose job it was to round up and escort all unregistered Natives in Cape Town to Langa.94 This was done with immediate effect and arrests made for November 1927 were 242.95 Certainly by 1936, after the increase in accommodation at Langa and the eventual closing of Ndabeni, much of the ‘cleaning up’ of the City had occurred, with most Natives being required to live at Langa. Yet many more avoided being brought under control through the establishment of informal settlements located at the three mile periphery of the city, beyond the space that had been produced and surveyed, or in the back alleys of District Six. Even so, it could be said that Langa, for a brief period, temporarily erased the contradictions of an Empire intent on preserving tribalism whilst simultaneously crafting Natives into ‘civilized’ and ordered labourer–visitors. Langa suggested for a time the imperative of making exploited subjects simultaneously present and absent could be made to work.

CONCLUSION

A look in the mirror of the city would have pleased politicos, administrators and architects in the mid-1930s. There, set within the optimistic frame of discourse and policies, they would have seen a White city of their making: ordered, regulated and without ambiguity. The Native (Urban Areas) Act had sequestered Natives into a singular bounded and fenced territory, a policed compound. An ‘improvement’ on the use of locations that had preceded the Act – the city was no longer as pock-marked with ‘African’ territories spread like a rash over its body.

No signs of ‘Africa’ were within this territory; not even thatch – that much-loved Arts and Crafts roofing material – was allowed to soften the roofscape of Langa. It was to all extents and purposes a White space – highly ordered with different ‘types’ of people allocated to different ‘types’ of accommodation. A look in the mirror would have shown how all married Christian Africans were living in the same area, in superior accommodation as befitted the order of things. Their two-roomed homes would have been adequate for their status – not quite the level needed for White residents but a mark up on the ladder of civilization nevertheless. Unmarried labourers would be carefully controlled and policed in barracks, their movements overseen by a nearby police station. All of this was rendered in whitewashed brick walls, in neat and orderly streetscapes with rows of terrace houses punctuated occasionally by churches and trees.

The city itself was showing signs of order. The ‘ugly,’ dense and fractured spaces of the older parts of Cape Town were being demolished, turned inside out, and ‘opened up’. Its ‘disorderly’ inhabitants were being investigated, re-housed, consolidated as a ‘race.’ Their new accommodation in free-standing and semi-detached cottages in suburban areas would have struck these mirror-gazers as being wholly appropriate to their station in civilization. They had been given their rightful place in the city, or rather, at the periphery of the city where they might better find their way to Self-hood. The mirror would also have revealed a group of White Capetonians, self-electing their identity as English – in hot pursuit of a Romantic English rural past in Pinelands, establishing England at the safe edge of the city, at a safe distance from the troubling and messy physical history of the city itself.

The Empire, it seemed, was just as it should be. Closer inspection would have revealed the mirror’s distorting surface, a torturing of the territory needed to produce the ordering fantasy.

As administered spaces of Whiteness, the stripped-down starkness of Langa and Maitland Garden Village nevertheless revealed their insistent difference, the lingering troubling presence of Otherness. It was in the labels on the drawings of Langa, the vague slippage of ‘room’ instead of ‘bedroom,’ it was in the lack of ceilings of the back-to-back houses built there and the implications for privacy and private property this suggested. But mostly the distortions were in the way that Langa and Maitland Garden Village had none of the Romantic charm needed to disguise the ordering and segregationist policies at the heart of the Garden City Movement. Within their heightened administrative regimes, Langa and Maitland Garden Village revealed the future repression that would be needed to control these Empire’s Others. Their location at the periphery of the city revealed the impasse at the heart of colonialism and its exploitative processes – how could ‘these people’ be both present and absent from the space of the city itself? How could they go on being housed at a burgeoning periphery that may ultimately become the centre? At what cost would the White space of the city be maintained? Aiming to avoid the ugly and troubling realities of industrialization, the Garden City Movement had, ironically, pushed everyone to the periphery of the city. And there, once again, Whiteness found itself surrounded by unsettling neighbours.

NOTES

1 Architect Builder & Engineer, vol. 6, no. 10, (May, 1923), p.10.

2 Cape Government Act 37, 1884, (Native Locations Act).

3 Cape Government Act 40, 1902 (Native Reserve Locations Act).

4 Cape Government Act 8, 1905 (Native Reserve Locations Amendment Act).

5 KAB NA 457: Minutes of Evidence. Commission on a Native Location for Capetown, October, 1900.

6 KAB NA 457: CNL: Robert Wynne-Roberts, (City Engineer).

7 KAB NA 457: CNL: John McGregor, (Chairman, Maitland Village Board of Management).

8 Baines, G., ‘New Brighton, Port Elizabeth c1903-1953. A History of an Urban African Community.’

9 Minkley, G., ‘“Corpses behind screens:” Native Space in the City.’

10 Consider the idea of the ‘location strategy’ as a means of social-spatial control in Robinson, J., The Power of Apartheid.

11 Cape Times 8 February 1900: Editorial, ‘The Aboriginal Immigrant.’

12 Cape Times 27 December 1899: Editorial, ‘The Kafir Problem.’

13 Bickford-Smith, V., Ethnic Pride and Racial Prejudice in Cape Town, p.160.

14 Notwithstanding a newspaper’s propensity for exaggeration and drama: Cape Times 27 December 1899: Editorial, ‘The Kafir Problem.’

15 KAB NA 457: CNL: George Behr, (Woodstock Mayor).

16 KAB NA 457: CNL: Joseph Corben, (Sanitary Superintendent).

17 KAB NA 457: CNL: Thomas O’Reilly, (Mayor).

18 Cape Times 27 December 1899: Editorial, ‘The Kafir Problem.’

19 Ibid.

20 KAB CCC NA 457: CNL, Letter from Noel Janisch, Under Colonial Secretary to the Town Clerk, 11 February 1901.

21 KAB NA 457: CNL: Compare Thomas O’Reilly (Mayor) to Samuel Tonkin (Mowbray Mayor).

22 KAB NA 457: Dr Jane Waterston.

23 KAB NA 457: Dr Jane Waterston.

24 KAB NA 457: CNL: Charles Matthews (Councillor) and George Behr (Mayor of Woodstock).

25 KAB NA 457: Robert Wynne-Roberts (City Engineer).

26 KAB NA 457: Thomas O’Reilly (Mayor).

27 Murray, N., ‘The Imperial Landscape at Cape Town’s Gardens,’ (unpublished M.Arch, University of Cape Town, 2001).

28 Cape Government NA 457: 17 October 1900.

29 Cape Government NA 457: 28 February 1901, letter from Mansergh to Chairman of Native Location Advisory Board.

30 Cape Government NA 457: 8 March 1901, letter from Mansergh to Noel Janisch, Under Colonial Secretary.

31 Cape Government PWD 2/1/30: 25 May 1901, letter from Mansergh to Newey.

32 Cape Government PWD 2/1/30: 9 April 1901, letter from Mansergh to The Chief Inspector of Public Works.

33 Cape Government PWD 2/1/30: 15 July 1901, report from J. Edward Fitt.

34 Cape Government PWD 2/1/30: 16 January 1902, letter from Mansergh to The Chief Inspector of Public Works.

35 Cape Government PWD 2/1/30: 24 November 1902, Requisition by the Clerk of Works.

36 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923.

37 Union Government 34-1914, Report of the Tuberculosis Commission, p.101.

38 Ibid., p.107.

39 Young, R., White Mythologies, p.147.

40 For a thorough analysis of this with regards the Tswana people, see Comaroff, J. and Comaroff, J., Of Revelation and Revolution, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), pp.287–322.

41 Union Government 34-1914, Report of the Tuberculosis Commission, p.102.

42 Ibid., p.104.

43 Ibid., p.104.

44 Comaroff, J. and Comaroff, J., Of Revelation and Revolution. The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier, p.280.

45 Saunders, F.A., ‘Municipal Control of Locations,’ paper read at the Thirteenth Session of the Association of Municipal Corporations of the Cape Province, held at Grahamstown, 10, 11 and 12 May 1920, pp.9–10.

46 See for example Cape Times 7 May 1923: Editorial, ‘The native is essentially a peasant; he is not an urban resident…’

47 Union Government Act 21, 1923 (Native (Urban Areas) Act).

48 Union Government Act 27, 1913 (Natives Land Act).

49 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/5/1/1/9: Special Committee, 16 October 1919.

50 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 16 April 1926.

51 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 6 November 1922, Letter to the Secretary of the Divisional Council, 6 October 1922.

52 As cited in Morris, P., A History of Black Housing in South Africa, (Johannesburg: South African Foundation, 1981), p.19.

53 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 28 August 1923.

54 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 April 1923. Report by the City Engineer dated 18 April 1923.

55 Miller, M., Raymond Unwin. Garden Cities and Town Planning, (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992), p.53.

56 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 4 July 1923.

57 Miller, M., Raymond Unwin, p.89.

58 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 28 August 1923.

59 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 4 July 1923. Report submitted by A.J. Thompson, 28 June 1923.

60 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 18 July 1923.

61 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 12 September 1923.

62 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 12 September 1923.

63 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 28 August 1923.

64 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923, the idea of Quarters came after meeting with the Cape Peninsula Native Welfare Society.

65 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923.

66 Foucault, M., Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison, p.197.

67 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923.

68 Robinson, J., The Power of Apartheid, p.59.

69 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923.

70 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 19 July 1924.

71 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 22 December 1924.

72 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 14 February 1923.

73 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 November 1923.

74 KAB Map M1/3380.

75 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 25 October 1927.

76 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 5 February 1924.

77 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 29 July 1924.

78 Robinson, J. ‘Octavia Hill Women Housing Managers in South Africa: Femininity and Urban Government,’ Journal of Historic Geography, vol. 24, no. 4 (1998), pp.459–81.

79 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 29 July 1924.

80 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/3: NAC, 15 October 1928.

81 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/3: NAC, 19 August 1929.

82 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 27 August 1924.

83 For reference to the importance of rooms and labels in the colonial context see John and Jean Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution, Chapter 6: ‘Mansions of the Lord.’

84 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 5 February 1924.

85 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 11 October 1923.

86 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 15 May 1923.

87 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/1: NAC, 19 November 1924.

88 Saunders, C., ‘From Ndabeni to Langa’ in Studies in the History of Cape Town, vol. 1, (1979).

89 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 9 June 1926.

90 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/3: NAC, 15 April 1929.

91 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 16 May 1927.

92 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 20 June 1927.

93 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 25 October 1927.

94 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/2: NAC, 18 October 1927.

95 KAB CCC 3/CT-1/4/10/1/1/3: NAC, 19 December 1927.