Doha, Qatar

Modern Doha, capital of the small but fabulously wealthy Gulf state of Qatar, is built on the very substance that made modernity possible: oil. The city is a mirror of the economy that created it. Expansion began as the world moved from Empire to free trade and exploded into free market globalised western-style modernity. The impact of global capital is not, however, the same wherever it falls and Doha has translated its meteoric projection into modernity in its own particular way.

First impressions, nonetheless, seem to confirm the view that globalisation produces identical products wherever you go. On the way from the international airport (already bursting at the seams with its bigger and better replacement under construction next door), you pass by suburban houses on the American model and quickly reach a centre dominated by international style buildings. As you take the Corniche Road, a six-lane motorway curving round the bay, you pass by modernist cultural and government buildings and look over at West Bay, a forest of glass-walled and wonderfully shaped offices, apartment buildings and hotels. When you reach your internationally-branded hotel all is either reassuringly or disturbingly familiar, depending on your point of view.

Above all, you are aware of the sheer newness of it all. But there must be a story beyond the glitz and the signs of relentless construction. As so much of the city is so clearly modern, the condition and culture of the people in the recent past will have had a major influence on what we see now. We need to start by looking at how it all came about.

BACKGROUND TO DOHA

Qatar is a north-pointing finger of desert sticking out into the Gulf of Arabia or Persia, measuring some 11,500 km sq. It lies at only 13 m above sea level. Narrower at its base, it is a distinct geographic entity. Historically, it fell under the influence or control of different Empires: Persia, Portugal, Turkey and finally Britain. It was recognised internationally as a distinct political entity led by the Al Thani sheikhs in 1868. It was occupied by the Ottoman Empire in 1872 but, following a successful armed revolt, they finally left during the First World War. In 1916, Sheikh Abdulla bin Jassim Al Thani signed a protection treaty with Britain that guaranteed Qatar’s defence from the sea and support in the event of land attack.

At that time, Qatar was poor with no significant agriculture or major sources of water. A few small towns around the coast were supported by fishing and pearl fishing was its major source of foreign income. The principal town and home of the ruling family was Al Bida, founded in 1825, which became known as ad-Dawha (‘the big tree’) or Doha. The demography of Qatar was a mix of settled seaboard Arabs and traders of Persian and Arabic origin in the coastal towns and nomadic Bedouins inland. The total estimated population was about 15,000 in 1920. Even this small population was driven to poverty, starvation and emigration when the Japanese developed cultured pearls in the 1920s and the impact of the ‘Great Depression’ from the USA crippled the small cash economy. This was the first major global event of many to affect Qatar.

Later global economic developments were much more benign. Worldwide demand for oil increased and the Middle East was identified as a major source. In 1934 Britain entered into a treaty granting further protection in return for granting a concession to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Oil was discovered in 1939 but exploitation was delayed until after the Second World War. In 1949, oil exports and payments for offshore rights began, as did the transformation of Qatar. This coincided with the elderly ruler abdicating the previous year in favour of his eldest son, Sheikh Ali Bin Abdullah Al Thani, who duly became Emir of Qatar (1948–1960).

Under a 1952 agreement with Shell, Qatar took 50 per cent of all oil revenues. This dramatic increase in wealth, along with social change and unrest in the Arab world following the Suez War in 1956, led to domestic unrest and pressure on the Al Thani family. Relying on British support, an embryonic government bureaucracy (staffed by foreigners) and a police force were created. In the 1950s, modern facilities were gradually introduced into Doha, including the first hospital, school, air-strip and telephone exchange. In 1960 huge offshore oil reserves were discovered and, under pressure to distribute the country’s new-found wealth outside his immediate family, Sheikh Ali bin Abdullah Al Thani abdicated in favour of his eldest son, Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali Al Thani (1960–1972). Limited reforms were introduced, including the provision of land for poorer Qataris.

In 1971, as Britain’s global power and wealth declined, it concluded its withdrawal from military commitments east of Suez, so ending the imperial era in the region. In the same year, Qatar withdrew from the formation of what would later become the United Arab Emirates, becoming instead a sovereign independent Arab Islamic state. At the time of its independence in September 1971 the population of Qatar had risen to over 100,000. The following year, Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali Al Thani was deposed by his cousin, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani (1972–1995), who consolidated his family’s position in the governance of the new state while introducing social programmes, including public health, education and pensions. During the 1973 global oil crisis Qatar created the Qatar General Petroleum Corporation and by 1977 it had nationalised all oil production. In a few years, from a dependent state and a colonial protectorate, Qatar had suddenly become enormously wealthy; by 1975 it had risen to enjoy the second highest GDP-per-capita in the world. Its last major political upheaval came in 1995 when Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani deposed his father while the latter was on holiday; Sheik Hamad then abdicated for his son in 2013.

6.1 Gross Domestic Product of Qatar, Percentage year-on-year rise averaged over three years

Source: Author (figures taken from nationmaster.com)

6.2 GDP per capita, world rankings for Qatar

Source: Author (figures taken from nationmaster.com)

6.3 Qatar’s population growth (Doha is approximately 80 per cent)

Source: Author (figures taken from Qatar Statistics Authority)

This brief outline maps the beginnings of Qatar as a modern oil-dependent Arab country and of the rapid growth and development of its main city, Doha. As one Qatari told me when I visited, ‘we have fast-forwarded a whole century’. But while a fully modern city has indeed grown up in a period of 40 years, the collective memory of extreme poverty and an insecure tribal past remain as real factors in the social, political and psychological life of Qatar. Another Qatari, from one of the major families, pointed out that his grandfather always went to bed with a loaded shotgun. This rapid history, from starvation to unimagined wealth within living memory, is essential for an understanding of the political reality behind the new institutions, the identity of the people, the pervasive Anglo-Saxon influence (first British and then American), and the interface between a tribal desert culture and global modernity. All of these things have and continue to leave their permanent mark on the city of Doha, which is home to 80 per cent of Qatar’s population.

From the time of the first Qatari oil revenues in the late-1940s to independence in 1971, the town of Doha expanded accordingly. By recent standards, the earlier expansion was modest but it established a pattern of development that would be repeated in the following decades.

6.4 City growth in Doha from 1947 to present

The first major land reclamation project began in the early-1950s, moving the waterfront in the city centre out by 100 m and creating a series of new urban blocks. This was followed by the Corniche Road in the early-1960s, following the direction of the most recent urban expansion and running in front of long-established water-frontage merchant’s houses. The loss of waterfront rights could be justified by the insanitary conditions that had developed in the shallow waters along the water’s edge. The Corniche Road remains today as one of the defining features of the city.

Both the city’s new waterfront and the Corniche Road were constructed by building the roads in the sea and then backfilling the space behind them, creating new real estate. This delivered high-value, state-owned land for building that was free from claims of historic land rights. Government House was built on the city centre reclamation and some ministries and government buildings were constructed on new land behind the Corniche Road. Land reclamation became, and continues to be, a key strategy in Doha for the creation of new high-status city districts.

Roads were also generally modernised. In accordance with the prevailing British typology, a number of by-passes or ring roads were constructed. These were named, successively and prosaically, ‘A Ring Road’ and ‘B Ring Road’ and so on. The A Ring Road joined the two ancient routes branching out to Saudi Arabia and the centre of the peninsula, and encompassed much of the 1950s town. The B Ring Road contained the 1960s urban expansion. By 1970, the C Ring Road was already under construction to contain further sporadic growth.

A new civic centre was created to the west of the old town in the 1950s. The Grand Mosque and Diwan al Amiri, or Royal Palace, were built around a ceremonial square centred on a landmark clock tower. Otherwise the architecture of the growing town was of no particular type or standard, often being on an ad-hoc basis by Egyptian or Indian draftsmen. Low-rise concrete apartments and shops were mixed with traditional houses sited along and between the new roads. Much of this remains as a dense, active and lively urban area but in a poor state of repair, with no resident Qataris living there; instead, these dwellings are let out to expatriate workers. The old houses that do survive are not held in high regard and, in discussion, many Qataris described some of the older parts of the town as slums suitable only for demolition. Today, whole inner urban blocks are being bought up by the government for comprehensive redevelopment.

This area has intentionally been left blank. To view Figure 6.4 as a double-page spread, please refer to the printed version of this book

As Qataris became wealthier they sold, redeveloped or let out their traditional courtyard houses in the centre, preferring to move to new villas beyond the built-up area. Older houses represented for many the poverty they had just left behind and so there was a demand for new villas modelled on luxurious foreign designs. The use of standard American and North European suburban house types, with the dwelling placed in the centre of a plot, was also dictated by the introduction of boundary set-back regulations. Still in force today, these regulations made the construction of new houses in the Qatari tradition, with rooms built around the perimeter of walled courtyards, impossible. Villas and residential compounds for foreign workers were also built on open desert land outside the town in a haphazard fashion, setting the pattern for the later development of what has become a huge suburban hinterland.

6.5 Outer area of Doha showing traditional homes mixed with ad-hoc 1960s and 1970s developments

THE REPLANNING OF DOHA

6.6 Masterplan for Doha by Llewelyn-Davies (1972)

Alongside the creation of the independent sovereign state of Qatar, the capital was re-planned. In 1972 the well-known British urban designers, Llewelyn-Davies, were called in to study the possibilities for future expansion. Their plan built upon the ring road system, as well as on the presence of Corniche Road, adding a further D Ring Road to the network. They also created a loose grid stretching behind the Corniche Road and south towards the airport to allow for future structured growth. Llewelyn-Davies also proposed some further land reclamation work to the east and to the north to ‘tidy up’ the coastline.

Shortly afterwards in 1975, the then Emir of Qatar called in the, now largely forgotten, Los Angeles star architect William Pereira as an advisor. He proposed a much larger area of land reclamation to the north – this is now called West Bay – which turned the straight northern coastline around to form a new bay, and also creating a destination for the Corniche Road. This project has had a major impact on the town and was intended to be a model development area. It included a Diplomatic District on the new shoreline along with one of Pereira’s trademark concrete pyramids as a Sheraton Hotel on the new promontory. This hotel was to be both a landmark viewed across the bay from the old town and a symbol of modernity. The Sheraton Hotel became part of a grand urban scheme which included a projected (but never executed) water spout on a new island in the bay and an axial boulevard, Grand Hamad Street, which was duly cut through the souks to focus on a pier-end lighthouse and the Sheraton Pyramid. Grand Hamad Street, now lined with modern bank buildings and featuring a crossed-scimitar ceremonial gate, remains as an uncomfortable insertion into the small-scale streets and alleys of the old town.

6.7 Plan of central Doha showing key elements

6.8 Sheraton Hotel by William Perreira Architects (1983), with West Bay behind and to the right

6.9 The formal civic gesture of Grand Hammad Street and its line of banks

RESHAPING DOHA

By the mid-1980s Doha had become a fully-functioning capital with new ministry buildings, National Theatre, National Museum and National Bank. By 1985 the population had tripled from its 1970 level to 320,000 people. After nearly two decades of world-class wealth, however, in the mid-1980s the global economic tide was turning. By 1986, oil prices had dropped to nearly one quarter of their 1980 price, and, along with other OPEC countries, Qatar’s rapid financial growth stalled. GDP remained static or slightly dropped for twelve years from 1982, and expenditure was cut on public projects such as building works in Doha.

As noted before, in 1995 the Emir, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani, was deposed suddenly by his Sandhurst-and-Cambridge-educated son, Sheikh Hamad. The following year the economy received a substantial boost as Qatar began to ship Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) to Japan. Natural gas had been discovered in 1971 and Qatar’s gas fields were found to constitute the world’s largest single gas reservoir. Today, Qatar holds the world’s third largest reserves, and at present levels of extraction there are 200 years of supply left. In 1995, as a result, Qatar’s GDP began upon a steady rise that continues to this day.

The accession of Sheikh Hamad bin Kahlifa Al Thani therefore corresponds to the start of the new global age. In 1993 the Russian and Indian markets were liberalised and in 1994 China reformed its exchange and trade laws. Sheikh Hamad, aware of the emerging changes in the world order, set in motion what can only be called a revolution in the social and political order of Qatar. In his words, as quoted in the New Yorker on 20th November 2000: ‘We have simply got to modernise ourselves. We’re living in a modern age … You cannot isolate yourself in today’s world.’

The steps taken to modernise Qatar in the last ten years are impressive. The Ministry of Information was disbanded and censorship abolished. Women were given the right to vote and stand for office. A ‘Qatar Permanent Constitution’ was approved by referendum in 2003 which, amongst other principles stipulates that there will be ‘no discrimination on account of sex, origin, language or religion’ and establishes an elected legislative Advisory Council. The Emir’s second of three wives, Sheikha Mozah, has been taken a high profile in the promotion of women’s rights and in the advancement of education generally. On the world stage, Qatar hosted the ‘Doha Round’ of the World Trade Organization in 2001 and the 15th Asian Games in 2006. Qatar will hold the 2022 World Cup tournament. The global significance of the Emir’s support for Al-Jazeera, the only uncensored Arab satellite television news channel, and based in Doha, cannot be underestimated.

The city of Doha today has grown to a population of an estimated 1,450,000 in 2011 living in its metropolitan territory. As noted, only 20 per cent of its citizens are Qataris. The current dramatic growth in the city will be as much an expression of the changes of the last 15 years as the legacy of the preceding decades. As I was told by the Manager of the Urban Development Department within the Urban Planning and Development Authority: ‘When Emir Sheikh Hamad was directly modernising the country economically, socially and politically he took great interest in urban and architectural issues.’

CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DOHA

From the first days of its oil revenue, Qatar has seen the rapid introduction of wealth and modernity into a traditional society largely based on a marginal economy. Unlike Europe and North America, there has been no philosophical ‘Enlightenment’, no trial-and-error development of civil institutions, and no cultural or political evolution in parallel with the growth of an industrial and consumer society. The introduction of the apparatus of modernity includes its undeclared history, which can create tensions and conflicts.

As communications increase and international capital is liberalised, those concerned with the support and supply of the industrialised and consumerist society are drawn into its net. This form of modernity began in the North Atlantic nations and its later manifestations bear their stamp. The phenomenon is called globalisation and where it impacts on previously unaffected societies it sets in motion a dialogue between the global and the local or the modern and the traditional. This is a worldwide process but its manifestations are always local. The combination of rapid change and huge wealth in Qatar throw this dialogue into sharp focus.

The development of Doha is bound to give expression to the friction between the global and local, but this may not be immediately evident to the visitor. While by far the larger portion of the current population comes from elsewhere (in a short visit I met people from other Arab countries, Lebanon, India, Philippines, Nigeria, Australia, Canada, USA, Japan, and Russia), I was told more than once that expatriates feel that ‘you’re always a foreigner here’, and naturalisation is not an option. The city belongs to the minority native Qatari population and so the way they identify with their rapidly changing capital city is relevant.

In discussion with Qataris about their personal identity, the response I got was consistent. Identity was about the family, the tribe and lineage. The nation was occasionally mentioned but so was the larger Gulf Arab community. Even when pressed on the role or place of Doha as a city, it did not have any significance in the individual’s perception of themselves in their society. Comments included phrases such as ‘the identity of the Qatari is inside himself, not the exterior’, and ‘there probably never was a Qatari identity and if there was it was never linked to the physical aspects of the place’, and ‘when you come home from abroad you look for the manners of the people, not so much the place’.

At the same time there is in Qatar a consciousness of the need to maintain or create a physical identity and of the dangers of outside influence. The Curator of the National Museum said: ‘We have a tangible heritage in Qatar, our archaeology and our history, but we are in danger of submerging the old city.’ One Qatari told me that there is a ‘tension between traditional and modern design, we are now moving to a change in the culture and custom of Qatar from heritage to modern’, and another that ‘the foreigners we choose are not the right ones’. A young Qatari woman stated that ‘we are copying international things but trying our best to maintain our identity’. And yet another told me that ‘in reality we don’t have much physical heritage’. However, Ibrahim Al Jaidah, a leading architect in the city, said more optimistically: ‘I dream that we can turn this identity into something of our own’.

6.10 West Bay, with its cluster of international-style skyscrapers built round a shopping mall

RECENT DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITY IN DOHA

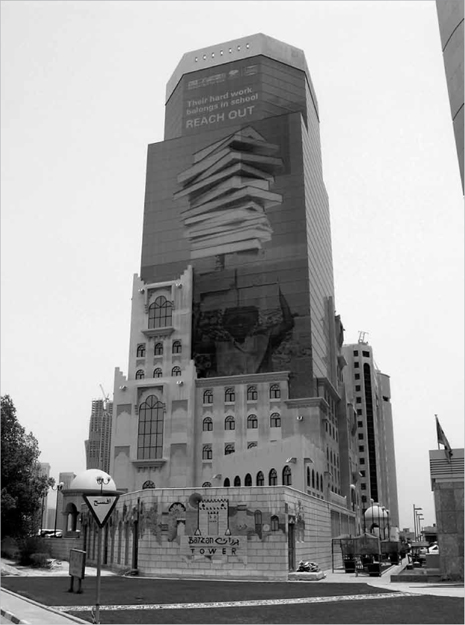

The most obvious expression of the new global North Atlantic modernity is West Bay. In the early-1990s, on the land behind the landmark Sheraton Hotel, Sheikh Hamad, in the words of the Manager of Urban Development, ‘decided to change the masterplan so we can have a modern city’; he duly abolished the previous height limit of ground-floor-plusten storeys. The outcome is a group of high-rise buildings, centred on the other global type – a huge shopping mall. This totally eclipsed the landmark status of Pereira’s Sheraton hotel. The start-up stimulus for this ongoing commercial development was provided by a take-up of office space by government departments. Most of the designs are the standard global glass-walled tower, some extravagantly modelled and some by star architects. Currently suspended due to concerns it might interfere with traffic at Doha International Airport, but apparently soon enough to join them is a very tall and super-slim 550 m tower (with a design seemingly re-cycled from the failed Grollo Tower in Melbourne, Australia) by Qatari Diar, the state development company. It would be only second in height to the Burj Khalifa. This will act as a landmark for a huge convention centre, reinforcing Doha’s aspirations to become a high-status international conference venue. On closer examination, however, amongst the shiny towers are clear attempts to introduce a regional design type, mostly similar to American post-modernist towers but with Arabian detailing. Some, such as a version of Jean Nouvel’s Barcelona tower now under construction, add abstracted Arabian details to familiar high-modernist types. On the entry to this area from the Corniche is the Barzan Tower with its traditional base and glass-walled top – a surprisingly eloquent expression of the unresolved global-to-local dilemma.

6.11 Attempts to build a distinctive Arab (if not Qatari) style of glass highrise in West Bay

6.12 The Barzan Tower at the entrance to West Bay from the Corniche shows the dilemma of creating a global-local or modern-traditional fusion

6.13 Strip mall in the suburbs of Doha

At the other end of the scale, the city is surrounded by vast suburbs of villas and gated ‘compounds’ complete with roadside strip malls, like the worst American suburban sprawl. The villas are often those of an American suburban type with illiterate versions of something vaguely traditional from the region or classical Europe. But quite unlike the North Atlantic suburb, these villas are all surrounded by high walls. While Qataris were keen to exchange their small courtyard houses for villas, they would not sacrifice their culturally-rooted standards of family privacy. In between these walled enclosures there are large and small areas of undeveloped land, dusty and seemingly uncared for. While the narrow lanes or sikkats between the old houses had been looked after by adjacent properties, this tradition clearly did not carry through to the wide residual spaces in the new suburbs, with unfortunate consequences.

Out in the suburbs are two quite different but explicit representations of North-Atlantic culture: the Villagio Shopping Mall and Education City. The popular and huge American-style Villagio Mall is made up of a half-digested pastiche themed on renaissance Italy, and is incongruously attached to the modernist ‘Aspire Tower’ built for the 2006 Asian Games. In the midst of a large car park, the Villagio Mall has a cartoon collection of bits and pieces from Italian cities disguising the blank outside walls and a Disney-style interior of what is meant to pass for Italian street facades under a painted cloudy blue sky. In the centre is a canal, complete with gondolas, and at one end a skating rink open to the mall.

6.14 Post-modern suburban houses behind high walls with uncared for residual space

6.15 ‘Aspire Tower’ for 2006 Asian Games, now with link to Villagio Mall

This area has intentionally been left blank. To view Figure 6.14 as a double-page spread, please refer to the printed version of this book

6.16 Villagio Mall with its Italianising details making a vast suburban mall

6.17 Interior of Villagio Mall with its painted sky ceiling and imitation Italian street

At the opposite intellectual extreme but still culturally contiguous is Education City, a campus of outposts almost exclusively from American universities brought together by the Qatar Foundation, chaired by Sheika Mozah. Cornell University, Carnegie Mellon University, Georgetown University, Texas A&M University, Virginia Commonwealth University and Northwest University are represented. While the institutions are generally American, the list of architects reads likes a global Who’s Who of the profession: Pelli, Koolhaas, HOK, Atkins, Legorreta and others. The key buildings are by Arata Isosaki including one of the most extraordinary attempts at synthesising international modernism and Qatari identity, the Education Convention Centre. This is a big dumb glass box fronted by a vast ground-to-eaves representation of the trunk of the Sida Tree (the logo of the Qatar Foundation and the symbol of the knowledge of the Divine from the Koran).

In Doha’s city centre, the struggle to navigate between Qatari identity and global modernity is more complex. Government buildings are often just low-rise variants of the universal glass box but two major buildings stand as visible symbols, not so much of local identity as of a wider global mission – in the words of a local Qatari cultural institution – ‘to diffuse the culture, ethical values and principles of Islam to mankind’.

6.18 Education City campus with various US university outposts

6.19 Education City Convention Centre by Arata Isozaki; the concrete structure imitates the Sida Tree, symbol of the Qatar Foundation

6.20 Museum of Islamic Art (2008) by I.M. Pei

The Museum of Islamic Art was opened with great fanfare in late-2008. It sits on its own man-made island and is approached down a grand avenue from the city centre. Its nonagenarian American star architect, I.M. Pei, said he was looking for ‘the essence of Islamic architecture’ and found it in the 13th-century fountain pavilion added to the 9th-century Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun in Cairo. Pei drew on ‘an almost Cubist expression of geometric progression from the octagon to the square and the square to the circle’, and a ‘severe and simple’ Islamic tradition that he feels has a satisfactory affinity with the abstract principles of international Modernism. His building is, however, much more than a display of its fabulous collection and must be seen in relation to the objectives of a nearby institution, the Qatar Centre for the Presentation of Islam, or Fanar (the beacon), which also opened in 2008. This proselytising organisation is housed in a prominent building at the end of the Grand Hamad Street, designed by a little-known Egyptian architect, Husam Al-Ahmadi. It uses more literal traditional Islamic decoration and has at its centre a tall spiral landmark minaret said to be derived from the famous 9th-century minaret in Samarra, Iraq – but it is in fact closer to a 13th-century Egyptian version found in the same Ibn Tulun Mosque that inspired I.M. Pei, symbolically (but possibly fortuitously) reinforcing the relationship between the underlying agenda for both of these buildings.

While these landmark structures look to worldwide Islam in mission and design, two other urban projects in central Doha represent quite different approaches to maintaining a local built identity in a city with a minimal built heritage.

6.21 Qatar Centre for the Preservation of Islam (2008) by Husan Al-Ahmadi

The Souk Waqif is locally famous as a complete recreation of the original historic souk alongside the old waterway, or wadi, which led down to the port. The project was initiated in 2004 by Sheikh Hamad out of a concern that all evidence of the old town would be lost. Instead of a restoration, the souk is in fact a complete reconstruction of its pre-1950s state based on evidence from what remained, as well as photographic records, personal recollection and a fair bit of imagination – all put together by the Ohio-educated Qatari architect, Mohammed Ali Abdullah. The result has the basic form and appearance of an old souk but the character of something new: surrounded by car parking, all of the same age, and all of the same deliberately coarse cement render with ubiquitous projecting mangrove poles. In discussion with locals, reactions varied from enthusiasm to sadness, but a young woman was typically more concerned with the way of life of the people than the architecture, telling me: ‘The old souk may not be real buildings but the way people use it, the opening and closing of the shops, the patterns of use are all the same.’

6.22 Souk Waqif, a complete recreation of the old souk on the same site

6.23 Typical street in the outer section of the old town which is to be demolished for the Msheireb project

Taking a different direction, the Qatar Foundation purchased an adjacent urban district and commissioned the American international urban planners and landscape architects, EDAW (since subsumed within the giant global practice, AECOM), along with the British multi-disciplinary firm Arup, to completely re-plan the area based on an almost total demolition of the largely mid-20th century small shops, businesses and apartments. The tidied-up comprehensive redevelopment, called the Msheireb project, is based on a tight pattern of traditional narrow sikkats and courtyard urban blocks, retaining only a few old houses and the routes of two historic streets (see Plate 10). It is hoped that a smarter and cleaner precinct will encourage Qataris to re-inhabit the city centre. A design competition for the three key government buildings and the design coding of the future development was won by the established UK firm, Allies and Morrison. At this early stage, while the street planning follows the now widely-accepted principles of traditional urban design by drawing on local precedents, anything local in the architecture seems to be so abstracted that the European and even London origin of the architects shines through. This huge scheme, being built in five phases and covering 31 hectares, is currently scheduled for completion in 2016.

Moving from literal re-creation in Souk Wafiq to modern contextual abstraction in the Msheireb project is but the next stage in the 50-year struggle to find a balance between the powerful culture of globalised architecture and urbanism and fragile local traditions. The success or otherwise of the creation of a Qatari character in the Msheireb project will not be evident for some years to come. It might, nonetheless, stand up well against other ongoing projects.

6.24 The Msheireb project by AECOM/Arup/Allies and Morrison

6.25 ‘The Pearl’ development on the northern edge of the city

6.26 Lusail district planned for the north of Doha

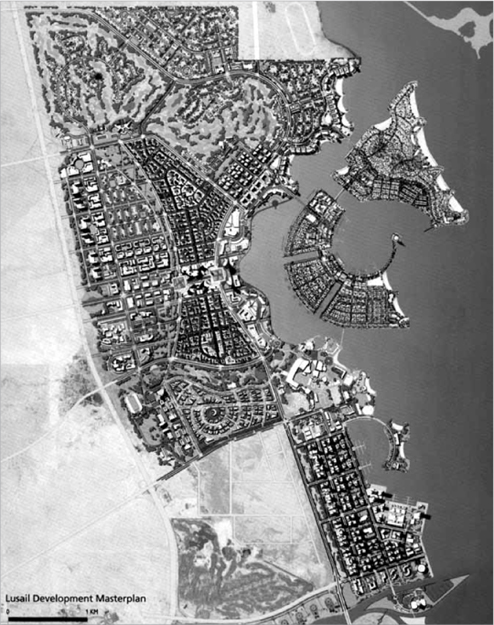

To the north, a large new resort-style waterfront development called ‘The Pearl’ is under construction for 50,000 inhabitants. Advertised with illustrations of Venice and an attractive girl in a hijab, the only relationship with Venice is the presence of water. Instead, the standardised designs are decorated with Arabian details. Occupation has already started, with anticipated completion for the scheme in 2015. Beyond this, 35 square kilometres has already been prepared by Qatari Diar to make way for Lusail, a new urban area with a projected population of 445,000. Its models and illustrations show the by now familiar huge glass towers and separate areas for villas and shopping with localised details added to American building types. The promotional literature speaks of ‘distinctive features that celebrate traditional Qatari and Islamic architecture in a striking, contemporary way’, thereby unwittingly capturing the very dilemma that underlies all development in Doha since the early-1950s.

With relaxed land ownership rules, the marketing of these new urban areas is being directed to foreign as well as local purchasers, and consequently progress has been slowed by the global recession. Rents in Doha generally were down by 35 per cent in 2009 due to declining demand. The second highest GDP per capita in the world, and generous financial support for Qataris from the national budget, however, means that this will probably only be a temporary slowdown, largely affecting expatriates. I certainly heard little concern from locals about any long-term impact of the current global recession, and indeed rents have already started to rally.

Sustainability, however, is only just emerging as an issue in Doha. In 2009 saw the launch of the Qatar Green Building Council, coupled with calls to abandon glass towers and, in the phrase used by Issa Al Malahni in The Peninsula newspaper on 19th March 2009, to ‘go back to the DNA of [Qatar’s] ancient building designs’. Given the scale of historic Qatari building and the scale of development in the last twenty years, this would require a seismic transformation and there seems to be no sign of any reining back of the cult of star architects or grandiose urban gestures. Low densities and glazed high-rise buildings are envisaged for Lusail for many years to come. A new public transport system is planned by the German firm PTV to counteract the almost totally car-based transport of the city. But with petrol at around $0.25 (15 pence) a litre, plus huge and sprawling suburbs and the ubiquity of four-wheel-drive vehicles, any public transport system in Doha would most likely be used predominantly by the poorer expatriate population. With summer temperatures at 45°C, life in Qatar is made tolerable for all sectors of the population by air-conditioning in buildings and vehicles, so much so that in 2004 the UN ranked the country as the highest-per-capita carbon emitter. The reality of environmental sustainability will take a long time to catch up with the rhetoric in Doha (if it ever does).

FUTURE PROSPECTS FOR DOHA

As Qatar looks to the future, how will Doha change? In 2005 the Urban Planning and Development Authority launched an invited competition for a new national masterplan to take the country through to 2025. This was won by a Japanese firm, Oriental Consultants, who in September 2010 presented their Qatar National Master Plan, which sets out a vision to make Doha the ‘most liveable’ city in the Persian Gulf region. It remains to be seen if this plan fares better than the still-current 1994 plan (also intended to last for 25 years) by the American firm, Louis Berger, which set up zoning standards, development policies and design guidelines as well as a planning council to administer the plan. I was told that because ‘unexpected political and economic changes’ overtook that plan for Doha, only 50 per cent of its proposals have survived. Whatever formal systems and orderly processes are set up by foreign firms, familiar with committee-based regulatory systems, these are always vulnerable to revision through the long-established family and hierarchical patronage (or majlis) system exclusive to the Qatari community. Also of critical importance is the make-up of Doha’s population, with the sharp divide between native Qataris and the large workforce drawn from overseas countries. As noted before, Qataris today constitute around 20 per cent of the overall population, a proportion equalled also by other Arabic residents, Indians and Pakistanis; the remaining 20 per cent consist of Iranians or other nationalities. There is also a striking gender imbalance, with males being around 80 per cent of the population of Qatar due to the massive influx of non-permanent immigrant workers; this latter group also totally skews the age distribution of the population, since most are males from their 20s–40s who have come to seek work in Doha.

In the Msheireb project, the introduction of traditional urbanism may herald the start of a move from big-scale anonymous urban design to closer-knit vernacular planning. Much will depend on whether Oriental Consultants are genuinely in tune with this new direction in urbanism. The global-to-local or modern-to-traditional architectural dialogue, however, shows no sign of resolution. There are regular official statements aspiring to a combination of modernity and tradition which fail to recognise that imported and globalised North Atlantic architectural modernity was developed precisely as an antithesis to tradition. Most American and European architects who are now building in Doha would never combine these concepts for designs in their home countries. As architecture inevitably reflects social, political and economic developments, if there is to be a change there it is here that we should look for the future. The direction of change in Qatari society is defined by the new Permanent Constitution. This must be seen, complete with its democratic underpinning, not as a westernising reform but rather as a modernising and formalising of traditional Muslim and Arab governance. Alongside the new constitution is a policy for the ‘Qatarization’ of society – in other words, the re-assertion of Qatari institutional leadership. If Qataris can use their (often foreign) education as a springboard for a rediscovery of their cultural heritage, instead of a mimicry of global culture, then a quite different and unique kind of architectural modernisation can take place that develops those built traditions that help to define Qatari culture.