Doha Renaissance: Msheireb Reborn

This chapter is about how to build contemporary architecture in Doha, the fast-changing capital of Qatar. One translation of the word Doha in Arabic is ‘a place in the desert which is habitable’. But is the city really habitable, with temperatures in the high-40s©C and even low-50s©C for a few months each year, combined with its dust-ridden air and extreme humidity? Thanks to air-conditioning and the motor car, the answer is ‘yes’. However does Doha offer as comfortable a lifestyle as it could, and if we look into the future, can this lifestyle be sustained or, even better, improved for citizens?

I will focus on a project for the rebirth of a significant piece of Doha’s city centre, just south of the Amiri Diwan and west of the newly revived Souk Waqif. This ambitious project is being brought about by Msheireb Properties, an offspring of the Qatar Foundation, under the leadership of Her Highness Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser. The project began as the ‘Heart of Doha’ and indeed, when looking at the city’s radiating plan, it lies right at the heart of the old city. Now it is being called Msheireb, the original name of this neighbourhood and which means ‘Place of Sweet Water’. The Msheireb project consists of a high-density, medium-rise, mixed-use masterplan, covering about 35 hectares. The masterplan is by Arup and AECOM, the latter company having acquired EDAW, the design firm originally involved the project. My own part in the team, from the early days, as the lead partner on the project with Allies and Morrison was to act as the ‘architectural voice’ of the project. The discussion in this chapter will be specific to Doha, but it also relevant to the wider region where the rate of change, the level of ambition and the climate are all extreme.

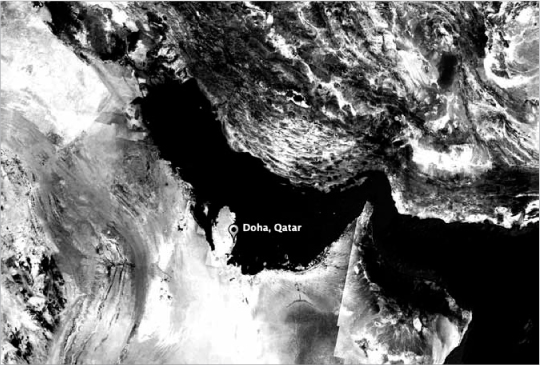

18.1 Location map of Doha, Qatar, within the Gulf

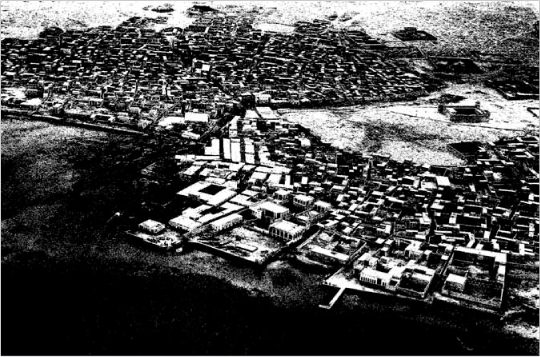

18.2 General city plan of Doha showing the denser old centre next to the corniche

So what do I mean by rebirth or ‘renaissance’? I am referring to the re-awakening, in a new form, both of a lifestyle and of an architectural language. In the words of Her Highness’s brief, we should be ‘looking to the future whilst being rooted in the past’. The image of a tree has under-pinned our thoughts. The roots run deep, to a large extent unseen; meanwhile the new growth flourishes; both are connected, and so it is a continuum.

18.3 The tree: rooted in the past, flourishing into the future

So, looking at the past, were things better in the old days? In some respects, yes, and, in those ways, we should learn from and reflect them again now. Apart from the unarguable aim of achieving the highest levels of comfort and well-being for the people of Doha for the long-term future, we are also in search of a strengthened sense of belonging. In terms of the built environment, I would suggest that a sense of identity is a pre-requisite for ‘making the most’ of urban life, and it is reliant to a large degree on connecting to the past. In Doha this sense of identity seems to be largely dormant, and it is the aim of Msheireb Properties to help to reawaken it.

18.4 West Bay in Doha from the air

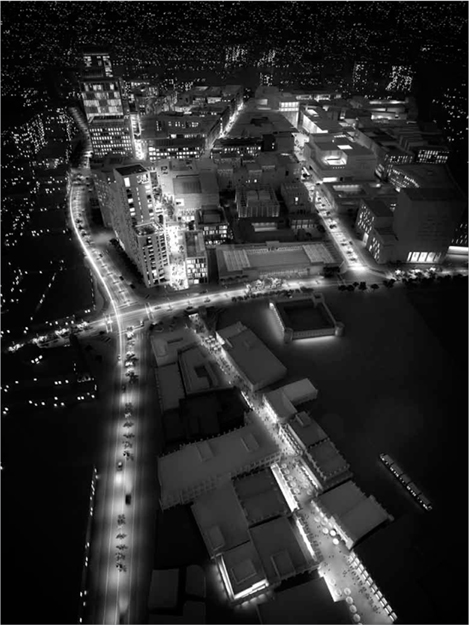

The identity of Doha is already, in some respects, very strong. If we look from above at the man-made road known as the Corniche, with the landfill area known as West Bay to the north of the city centre – the masterstroke of William Pereira’s master-plan in the mid-1970s – we can see how the city is continually ‘looking back at itself’ across the water in a memorable way. This is surely the single most identifiable feature of the city and it gives a strong sense of orientation, at least when one is down by the water. In every other sense, the Corniche – and the city centre as a whole – offers much room for improvement, both in terms of urban lifestyle and architectural language. Cars currently dominate, and buildings sit as objects in space, rather than forming edges to streets and spaces which at present lack urban definition. It is hard to walk about, even when the weather is good (for at least half the year), as there are not enough pavements, crossings, and, most importantly, there is almost no shade.

18.5 West Bay at street level

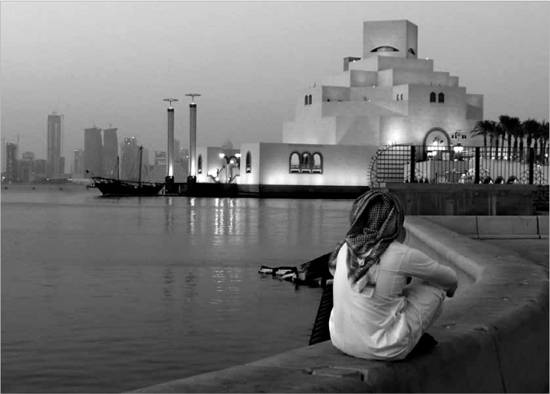

18.6 The Museum of Islamic Art by I.M. Pei, with the new city rising behind

The Corniche connects two key parts of the city: the old centre, which now contains the Msheireb project, and the new developments in West Bay. They talk to each other across the water and Msheireb definitely has something to teach West Bay. I am a firm believer in West Bay as a place with great potential. I think it is good for Doha, but only at the ‘macro’ scale, and as just a chapter of an as yet unfinished story. At the moment this is not a place for pedestrians. It is not a place where the street is alive. Indeed in summertime, it is truly uninhabitable unless you are in a car or an air-conditioned building. Nonetheless, it is a highly successful new address within the city, and it is part of the old town/new town dynamic which – with emerging landmarks such as I.M. Pei’s Islamic Museum – is setting Doha in a good direction for the future.

The commercial towers of West Bay, whatever one thinks of their individual designs, are spectacular from a distance, particularly at dusk – but that is not enough. They do not cohere: if they were a choir, their music would be a cacophony. As objects they do not make places for people, other than for those inside their glass-clad, air-conditioned forms. Most importantly they do not contribute to a sense of identity which grows out of, or fits into, Qatari tradition. In other words, they are not rooted.

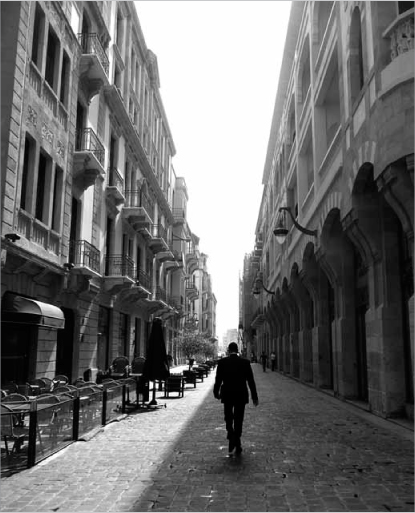

To complement and contrast with this, the Msheireb project envisages a city of arcaded streets and carved-out urban spaces. It offers shade, pedestrian priority and human scale. For Qatari families, it offers an alternative to living in a box-like villa in the suburbs, surrounded by a wall where, to get anywhere, one has to get in the car. It also aims to offer a harmonious kind of architecture in which, whoever the architect is for a given block, the space between buildings is more important than the buildings themselves, and the common architectural language – in whatever accent it is spoken in – consistently connects this important piece of the city back to its roots. Although from a very different part of the Middle East, the old centre of Beirut is a relevant example of this kind of successful urbanism.

18.7 The floating structure of the Msheireb Enrichment Centre, by Allies and Morrison, with the backdrop of West Bay

18.8 Solidere in central Beirut, Lebanon

The story of Msheireb begins, as with so much of the history of the city, on 11th October 1939. ‘Petroleum Development Qatar. Have had slight show of oil in their test well near Zekrit. Drilling continues’ read the telegram sent by the British political agent in Bahrain at the time. If one looks at old photographs of Doha in 1952, one can see clearly the ‘old town’ of Doha – developed over centuries and based on fishing, pearl diving and trading. Slightly to the west, the ‘new town’ began to develop fast during the 1950s. The Al Koot Fort and the Eid Ground, which used to be right on the edge of the city, now lie between the older and the newer parts. Al Kahraba Street was laid out then but not yet built up. Legend has it that its soft curve arose from the haphazard rolling out of Doha’s first electrical cable (not quite pulled straight) by a British engineer.

The old photographs of Doha also gave essential clues as to how Msheireb could meet Her Highness’s brief. Given that our urban site was in the area that was being developed throughout the 1940s and 1950s, modernity was clearly then a driving force; however, there was still at that point a connection between the city of the past and that of the future. Every street held old memories, and, although many of the streets of the Msheireb site are somewhat tired and unloved now, their stories are there to be cherished – and new chapters are still to be told.

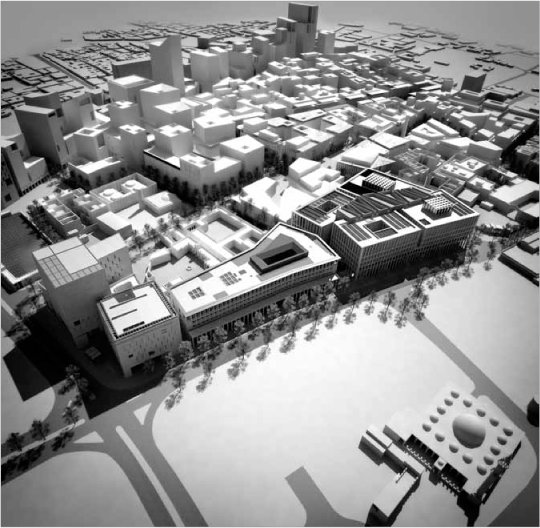

The Arup/AECOM masterplan for Msheireb is a tour-de-force of how to balance geometry with informality in response to the historic irregularities of the site and to the ‘organic’ urban tradition of the wider Gulf region (see Plate 28). It is also an exemplar of sustainable urban design at the macro-scale, both in the context of Doha – in terms of the lifestyle changes it will offer – and the degree to which it can serve as a catalyst for urban change in the coming decades. A determining factor in the masterplan has been the local climate, and this led to a number of objectives: how to maximise shade and optimise the use of wind to keep public spaces cool; how in particular to make the ‘shoulder months’ between summer and winter as comfortable as possible; and how to promote pedestrian movement and minimise reliance on the car. To this end, the strong prevailing wind from the north-west has informed a north-south grain for the block layout, within which the roof forms are used to catch the wind, cast shade and harvest solar energy.

The master-plan is also ambitious in terms of the provision of shared infrastructure and the use of basements. This makes possible a fine urban grain, a traffic-calmed environment and sustainable energy systems on a larger scale. More importantly, however, it is a master-plan based on places and connections, old and new, and of activities and events. It is this complex mix of uses and the framework of carved-out urban spaces which I believe are the key to the plan. These make a setting for, and a physical manifestation of, memory past and memory future – and thus they make Msheireb a firm part of the continuum of Doha’s history.

18.9 Model of the Msheireb master-plan showing its fine urban grain

Msheireb is not the first significant change in the old city centre in the 21st century. Immediately to the east lies the Souk Waqif, an old market which dates back well over a hundred years. In recent few years it has been reborn as a place to shop, eat, drink and promenade, with huge success. Its style and its scale are firmly rooted in the past, without any particular response to the future, and in that respect Msheireb offers something different. However, in terms of urban space and spirit, there is a direct connection, in particular where the southeast corner of Msheireb meets the souk and the two worlds are joined to create a continuum.

One of Allies and Morrison’s roles within the master-planning team has been to draft the architectural guidelines. These are encapsulated in what we call the ‘Seven Steps’; in other words, seven guiding principles for all development in Msheireb project. The first step is ‘Continuity’; the general principle that there must be a link between the past and the future. All design has timeless qualities and we are continually reinterpreting the past in new ways. Whether it be the elaboration of a shading screen with the use of patterning, or the proportioning of a solid wall with openings made up of substantial horizontals and verticals, in either case, the new can ‘grow out of’ the old – and thereby achieve a relevance and powerful resonance with its roots.

The second step is the ‘Balance between Individual and Collective’. If we look at an ordinary street wall around the Souk Waqif, we can see that is made up of many buildings, each touching its neighbours, and together forming the urban backdrop. The elements are all related but, just like a family, every member is an individual. The street image has a visual richness and an engaging informality which seems to balance unity and diversity. None of the buildings shout ‘look at me’, but together they sing a harmonious song. Part of this particular harmony in the old city, which I believe is also relevant to Msheireb, is the style-less robustness of the everyday architecture; it is something evolved over centuries both for cultural and technical reasons. Step two therefore urges designers, except in selected landmark sites, to emulate this ‘team spirit’ and promote the primacy of the street wall. In this way, not only will we achieve a coherent piece of city but, in my view, we will realise the particular beauty of a richly variegated but cohesive street frontage – something which would be impossible if we encouraged every building to make its own statement.

18.10 Continuity as expressed by the Al Mana House in Doha

Step three is the ‘Relationship between Space and Form’. It intends to highlight the soft informality of the 1950s plan of Doha, a pattern of organic growth where the right angle is not dominant. On the basis that, with the occasional exception of object-like buildings such as the Al Koot Fort, the buildings form a kind of ‘urban clay’ – in that out of them are carved the streets, the narrow alleys (sikkas), the informal urban courtyards (barahas) which act as sitting places outside houses, and the major spaces such as the market place or the Burial Ground – then it calls for a common spirit to prevail across the site. This collective urban spirit is typical of development through the centuries all around the Gulf. Looking again at West Bay, we can see that there is no ‘mutual relationship’ between its object-like forms and the spaces between buildings. As a result, its urban spaces lack both quality and cohesiveness. If the majority of buildings were ‘edges’ rather than ‘objects’, the streetscape would become far more positive. Indeed the same principle applies to the individual dwelling in old Doha, where the interior space of the courtyard is traditionally the focus of activity, and is given a positive form. Even in the making of rooms and the massing of roofscapes, the spirit of ‘carved clay’ still prevails.

18.11 Sketch of Doha in 1952 showing its space and form

18.12 The fereej housing cluster redesigned for the 21st century in the Msheireb project

The fourth step deals with ‘Aspects of the Home’. We now return to the notion of ‘renaissance’, or rebirth, of a lost but fondly remembered lifestyle which is reinvented to suit the needs and expectations of the 21st-century Qatari family. The question underlying step four is: ‘Can we create a viable and truly appealing alternative to comfortable family life in a suburban villa, transposed into the city centre?’ In other terms, will we be able to bring Qatari families – whose parents and grand-parents grew up in the old city – back to the urban centre? Can they enjoy space and comfort that is not just equal to but better than they are now used to? I believe the answer is yes.

As a set of urban principles, this step ranges from the macro-scale to the micro. It sets out a direction for how neighbourhoods will be organised, how outdoor space (both private and communal) will be configured, how new homes should be arranged, and how entrances and rooftops can be made the most of. These ideas apply to apartments as well as family houses. One of the unusual, indeed groundbreaking, aspects of the Msheireb project is the rebirth of the urban fereej, the cluster of private family houses in a neighbourhood which share a communal courtyard garden and a communal meeting/entertaining building (majlis) for neighbours to use, which is also a place to receive male guests, and rooftop sitting areas. Much work has therefore been done on this aspect, looking at traditional Qatari courtyard houses as well as other house types. The smallest houses in the Msheireb are similar in size to a typical suburban villa in Doha, and many indeed are larger. Every house will have its own integral private garage, at the lowest level, beneath the main entrance floor and the communal garden. Meanwhile, the key to achieving the levels of privacy which residents will expect – in spite of living in closer proximity to their neighbours than they are used to – is the courtyard design. Houses will therefore be relatively closed to the outside street, with carefully modelled walls used to bring in daylight while maintaining privacy. On the inside, however, the courtyards will be very open, and will give residents the ability to open up the house for indoor/outdoor living when the weather is good.

18.13 Communal gardens as part of the new Qatari urban living

18.14 Solid walls provide privacy in the dwellings, yet the interiors are still flooded with light

Specific building details are also set out in the guidelines, such as ways of using mashrabiya screens to achieve privacy and shading, while also separating the formal part of the house from the family zone. As a lifestyle offer, this is certainly something very new for Doha, as well as for the wider Gulf region. To be able to live in an ample house of 700 m2 with a swimming pool on the roof, private courtyard and a communal garden with a shared majlis – and all within a few minutes’ walk of Doha’s best shops, hotels, cultural buildings, schools and public spaces, and the Souk Waqif, National Eid Ground and Amiri Diwan – will for some soon become a reality. To have a three-car garage at the bottom of your house, but then to find that you hardly need to use your car, it means less time spent in traffic jams and more time spent at home or out enjoying the city. It is hence a sustainable vision in a deeper sense than just reducing carbon footprints.

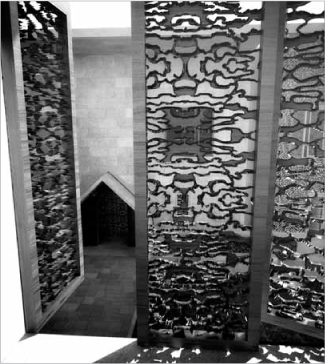

18.15 Privacy and shade are achieved with the use of mashrabiya screens

To return to the ‘Seven Steps’, the fifth step relates to ‘Aspects of the Street’. This refers to how one can create a successful continuum of urban spaces, connected to each other and to the surrounding context, in terms both of movement, activity and design character. The guidelines discuss the ways to reflect a strong urban hierarchy; how to manifest and celebrate differences such as between the grand public square of the project (Barahat al Nouq) and the quiet sikkas nearby, with an appropriate architectural eloquence. Step five also asks an important question: ‘How should buildings meet the ground, how do people relate to the new street frontages as they walk by, and, bearing in mind the heat, will they be comfortable on the streets?’ The designs suggest ways in which buildings and the spaces between buildings can make the street a positive place to be in, through the use of extensive shading, arcades and carefully tuned frontages.

18.16 The dwellings have ample space for cars but are set within a walkable city

If one goes today to Souk Waqif on a warm Thursday night and remember that, only five years ago, people wouldn’t have been out and about in the city centre in this manner (except perhaps on the Corniche), then one can see that this desire to meander, and to flow – be it for shopping, eating out or just watching people and bumping into friends – is very much alive and wanting to expand its territory. At the western end of the souk, where it currently comes to a dead end, is precisely where Msheireb will connect and pick up the flow of people that is already happening. It is from this point that a new set of journeys will begin; whether on the large scale or small scale, busy or quiet. These are journeys that will join up important new places such as Nakheel Square (the location for the new metro station at the south-western corner of the scheme), with old places re-born such as Kahraba Street or Al Rayyan Road.

18.17 Al Kahraba Street North, Msheireb, by Adjaye Associates and Burton Studio

Continuing the theme of creating a comfortable and sustainable environment – one that will be successful in the longer term – the theme of step six is ‘Designing for Climate’. This brings us back to being rooted in the past while looking to the future. New technology is opening up extraordinary horizons for low-energy design, especially when applied on the infrastructural scale of Msheireb project. However the old tricks are often the best ones and indeed ‘designing for climate’ is nothing new in Qatar. Old techniques such as the ‘breathing wall’ (malqaf), the shaded buffer zone (liwan or shanasheel), or simply the use of high thermal mass in buildings, are still highly relevant today. Whether such techniques are used as direct references or are reworked in new approaches to design, they represent a basic human impulse: ‘How do I achieve the most, or the best, out of the least’. Hence a significant part of step six goes beyond the basic need to deliver optimum performance with minimum energy and minimum waste. It simply seeks to offer choice to users. Can I open the window? Am I able to control my own environment? Can I enjoy being outside when the weather is good?

18.18 Malqaf, or ‘breathing wall’, in a traditional Qatari house

Finally, the seventh step is that of a ‘New Architectural Language’, an echo of the Italian Renaissance nearly 600 years ago. When Brunelleschi designed the Pazzi Chapel in Florence in1429, we only have to look at the column details to see that he was learning from ancient buildings such as the Pantheon in Rome, built thirteen centuries before. However, he was not copying them. Brunelleschi’s architecture was something radically new, both for his own age and in relation to his ancient sources. He had decoded the ‘architectural DNA’ of his culture and reconstructed it for his own time. The timespan of the Italian Renaissance was far longer than Doha’s more recent architectural history, but nonetheless it is a relevant parallel to the aims of Msheireb. The fact that there had been a loss of continuity between the architecture of ancient Rome and that of the Italian Renaissance is echoed by the fact that there has been a gap between the ‘timeless’ architecture of Qatar in the pre-oil era, and the metal-and-glass architecture of Doha today. The architecture of Msheireb seeks to bridge this gap.

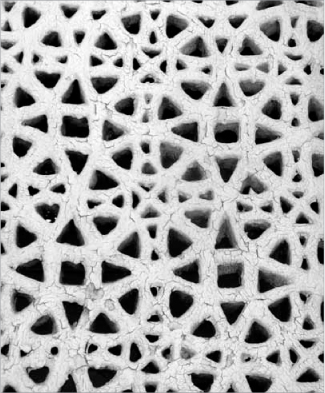

So what aspects of traditional Qatari architecture does step seven highlight as forming the basis for the grammar and vocabulary of a new language, and what will make this uniquely Qatari? Taking our key references from buildings such as Souk Waqif, the heritage houses already on the Msheireb site, and the coastal town of Al Wakrah just south of Doha, some clear themes emerge. The robust, simple architecture of the thick wall, with predominantly rectangular openings, is the dominant theme; this is then enriched with layers, recesses and the ‘split wall’ detail of the wind-catchers (malqafs) and the projecting danshals of mangrove wood, so valuable in those days that the poles were allowed to project, rather than being sawn flush. Within this overall design, areas of patterning are then used either as gypsum reliefs, to highlight important elements such as inner linings and doorways, or as mashrabiya screens for privacy and shade. Together it creates an architecture which comes alive in sunlight and shadow.

18.19 The play of shadow and light on old Qatari buildings

18.20 A traditional naqsh pattern as a screen

18.21 New door motif based on a Qatari mangrove pattern

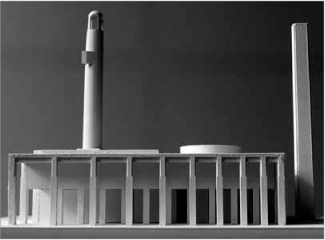

18.22 Model of the Msheireb Mosque by Allies and Morrison

The thick wall thus acts as the ‘clay’ out of which the softly irregular urbanism of step three can be carved. It is also the medium for sculpting the asymmetrical but balanced forms of the traditional Qatari skyline. But is this specifically a Qatari feature, or is it simply part of the architectural tradition of the wider Gulf region? It is clear that over the centuries, maritime communities all around the Gulf have been sharing many aspects of an architectural language. If we look at a sikka in Kish Island in Iran or a sikka at Al Wakrah in Qatar, they are almost indistinguishable. However it is the subtle differences which are most telling and hence the seventh step also calls on designers in the Msheireb project to find inspiration in the particular characteristics of Qatari sources.

In the three main zones (base, middle and top), architectural elements are illustrated as being potential roots and seeds from which the new branches and leaves of an authentic contemporary language can grow. Proportional details are examined, as is the use of arches within a predominantly post-and-beam language to emphasise entrances. The deep colonnade or balcony (liwan), the projecting bay window (shanasheel), the projecting beam (danshal) and the expressed rain spout (marzam) are all illustrated as potential references in the guidelines, as are the use of external stair cases with solid balustrades and the carved joinery elements for doors, windows and shutters. Materials and colours are other important parts of the guidance given for the Msheireb designers, since they are a key to achieving the level of cohesion described in step two, balanced with richness and diversity. Stone – albeit never traditionally used in Doha in the form of smooth-cut dressed ashlar – is also being encouraged, particularly on primary street frontages. The selection of stone, however, has to be held within the traditionally tight palette of soft whites, light greys and sand colours, and this also includes the most typical traditional Qatari finish, hand-smoothed white render. In terms of composition and hierarchy, we are seeking a spirit of asymmetrical balance which is found throughout traditional Qatari architecture. The modelling of roofscapes, or the modulation of parapet lines, or the positioning of entrances, are all informal but controlled. Doha’s skyline will thereby be enriched. This three-dimensional characteristic goes hand-in-hand with the ‘softened geometry’ of the traditional house plan and the ‘organic’ urban grain of historic towns and villages around the Gulf region generally (see Plate 29).

18.23 Msheireb Enrichment Centre by Allies and Morrison

18.24 Organic urban form mixing new and old in the Msheireb project

Different designers will thus come to Msheireb with different philosophies, and this indeed will be part of the quality and character of this new piece of city. It is essential that the emphasis on the past is used to add to, not detract from the authenticity and integrity of individual new works of architecture. Pastiche is out of the question. Our series of underlying principles of construction, building organisation and climatic response will surely form a primary link between the past and the future but, in a contemporary way. Direct quotations or references (literal or non-literal) can also be used to make the link, be they in terms of architectural elements or from other Qatari archetypes. For example, the language of dhows or tents may inform the roofscape of buildings, with timber and canvas being used for shading structures. Putting together this language is indeed an exercise in cultural decoding and, as with any such code, the solution is not obvious but the result should be meaningful.

The intention of these seven steps is therefore to establish a ‘base beat’ for diverse architectural approaches within the project; a ‘Qatari Contemporary’ vernacular. As with any vernacular, a common language can bring cohesion without suppressing diversity, expression or accent. Our intention as foreign designers working in Qatar is to prepare fertile ground for a ‘home-grown’, indigenous architecture to evolve. As gardeners we do not brings the seeds but we do help them to grow into healthy and deeply rooted plants.

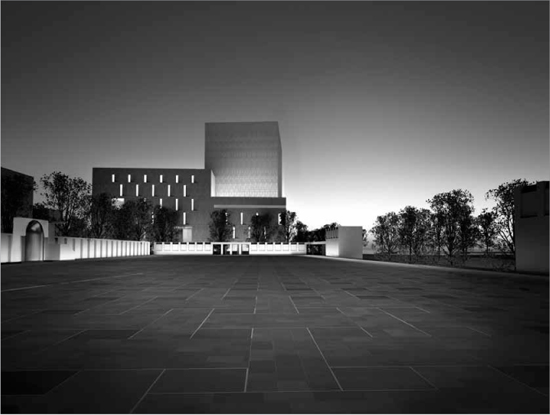

Allies and Morrison’s major project within the Msheireb exemplifies many of the above principles, and is currently on site. It is known as the Diwan Amiri Quarter and it comprises three government buildings: the Diwan Annex, the Amiri Guards Headquarters and the National Archive of Qatar. Together they form one of the primary frontages of the whole project, and a link between the site and its surrounding urban context. Our site is rich in memory and in terms of clues for a design response which can grow out of the location. To the north lies Al Rayyan Rd with the existing Amiri Diwan and the Majsid al Sheikh opposite, and the Corniche road beyond. To the east are the Burial Ground, the Al Koot Fort and Souk Waqif. To the south, the National Eid Ground and the low-lying heritage houses – recently reconstructed – provide a direct inspiration and a backdrop for the new buildings we are proposing. The site is 300 m long and irregular in shape, and these irregularities, which stem from its history, have generated the particular forms of our design. The siting of each building falls naturally into place, with the Diwan Annex at the western end, facing the southern axis of the Amiri Diwan; the Guards Headquarters in the middle, controlling the security of the site; and the National Archive at the eastern end, facing the Corniche, and turning eastwards also to face the Burial Ground and the Souk Waqif.

18.25 Diwan Amiri Quarter (Msheireb Phase 1), by Allies and Morrison, seen from the north-east

The brief for each of the three buildings by Allies and Morrison is unique, bringing its own response. Each building is rooted in a particular Qatari archetype: the fortified tower for the National Archive: the fort and courtyard dwelling for the Guards Headquarters; and the liwan-encased small palace (diwania) for the Diwan Annex. They act as a family of buildings, all related, but each one is seen as an individual. Beginning with the requirement that all office windows should be openable, the Diwan Annex has been given a double-layer liwan, made of simple post-and-beam stone construction, on all its external facades. This forms a security buffer and gives privacy and shade, while making useable balconies for each office and giving clear views. The outer layer of each facade differs in design in response to its particular solar exposure. The Diwan Annex is large – its footprint is about 130 m in both directions – and so to bring it back into scale with the grain of the Msheireb master-plan, it has been sliced into four pieces. Each of these four blocks has its own rectilinear geometry, but due to the non-rectangular street pattern, they sit at four different angles. Where they meet an irregular space is created, which we call the ‘Covered Street’. This is an enclosed and cooled space, providing a buffer space to the offices, but its facades have also been treated as if they were external, with galleries on every level and bridges connecting between the blocks. The roof of this space oversails the cornice line, helping to maintain its street-like feel. The ‘Covered Street’ runs through the heart of the building and will be the place of social interaction for the thousands of people working there.

18.26 Covered street within the Diwan Annex

The primary street frontage for all three buildings is along Al Rayyan Road to the north, forming a new backdrop to the Amiri Diwan, and the Masjid al Sheikh. Al Rayyan Road is one of the oldest streets of Doha, as witnessed by the line of existing diwania which form its strongly defined edges at the western end. It is being transformed into a ceremonial street with the ability to be closed to traffic for public promenading or for civic events. Meanwhile, the all-important security control mechanisms are integrated into ceremonial gateways. Part of the challenge of placing high-security government buildings in the context of an urban street has been met with the colonnades which run the full length of the site, joining the three buildings in our quarter. Unlike the arcades elsewhere in the Msheireb, these will not have shops and cafes; rather, they make a place where citizens can enjoy the ‘Lyric History’, an anthology of ancient poetry on the theme of Qatar’s history, which will be carved into the white marble-fluted walls running between the main entrances – while also forming a security cordon to vehicles.

18.27 New colonnade along the Al-Rayyan Road

The main entrances front onto Al Rayyan Road as part of this colonnade, and each one is elaborated with a language of patterning. Areas of pattern are used in bold and simple ways to highlight doorways, gates and inner linings. These patterns are not reproductions from elsewhere. They are uniquely generated from a number of Qatari motifs; from natural features such as the waterways of Al Khor, from archaeological treasures such as the ancient carvings of Jebel al Jessassiyah, or from found objects that are part of the site’s history. Together, these patterns combine ancient Arabic traditions of pattern-making based on an underlying rectilinear grid, with modern digital techniques, both in terms of drawing them out and also for production in stone and metal. This is another way in which the link is made between the past and the future, and between contemporary architecture and its context.

18.28 CNC-cut pattern in marble, which is then photographed, hand-traced and digitized to create the stone finish for the Diwan Annex

The main VIP entrance to the quarter sits between the Diwan Annex and the Guards Headquarters. The Guards block is set back behind the colonnade, while the facade of the Diwan Annex is brought to the front line. The Guards Headquarters is a carved and moulded building, both inside and out. Its low courtyard form is a contextual response to the history of the site and to the traditional houses immediately to the south, as well to the brief. Three floors of accommodation (one for each company of soldiers) wrap around the central parade ground, with communal spaces at ground level and the officer’s mess and roof terrace at the top. The stone facades of the Guards Headquarters echo the layered thick walls of the neighbouring traditional buildings. On the south side, white render is used rather than stone, in response to the historic Company House on the other side of the Sikka Mohammed, the winding lane which runs between the Diwan Amiri buildings and the heritage cluster of the masterplan. While the courtyard follows the irregular shape of the site, the building’s roof oversails the central space, with a rectangular cut-out that follows the primary geometry. This ambitious roof structure serves as a support for photovoltaic cells and a wind-catcher, while also shading the fabric of the building itself to reduce solar gain.

18.29 North facade of the Amiri Guards Headquarters by Allies and Morrison

18.30 Courtyard of the Amiri Guards Headquarters

At the eastern end, the design for the National Archive brings the theme of the historic urban patterns of Doha to a climax. This building wraps around the smallest of the three heritage houses, Radwani House, a remnant of the old city when this area was densely covered with houses, tightly packed together in an organic pattern, evolved over time. The site’s informal three-part geometry is extruded into three carved blocks built of stone and of differing heights to accommodate the three functions of the brief. The archive stack, held between the public wing and the support building, forms a focal point for views from the Corniche, the Burial Ground and the Eid Ground. The Radwani House is seen as a piece of ‘treasure’, both symbolic and actual, which becomes the oral history department for the Archive. The book stack is then raised above a grand columned portico, framing views of the old house, and making connections with the narrow sikkas and barahas found in the heritage and cultural quarters.

18.31 National Archive of Qatar seen from the Eid Ground

The National Archive is scaled to speak urbanistically from a distance and to reveal further layers of story-telling at closer range. Traditional details are reflected in contemporary ways. Carved stone cills project, echoing the traditional rain spout (marzam) detail, and casting changing shadows on the facades as the sun moves through the day. The National Anthem is carved at a large scale onto the east facade, to be read from far off, while calligraphy is used throughout the building to embody Qatar’s narrative traditions. In summary, the building is regarded both as a durable container and a lasting symbol for Qatar’s archive – the memory of a nation, past, present and future.

In conclusion, these three buildings – along with the other designs that are now on the drawing boards of a range of architects for the subsequent Msheireb phases – while being contemporary are also rooted in the past. They grow out of the place where they come from and they thus fit into the tapestry and identity of that place, with its memories, its forms, and its idiosyncratic character. In that sense, although our buildings, when completed soon, are going to be new, we hope that they will feel natural, resonant and harmonious (see Plate 30). The vision of Msheireb Properties is to create a lasting piece of city, and it is our hope that Msheireb will indeed become the starting point for a new Renaissance in Doha – both in terms of urban lifestyle and architectural language, and one which will continue to be enjoyed by future generations.