Dubai, UAE

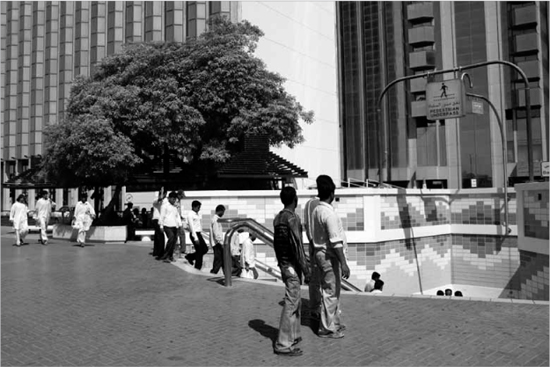

In less than a century, the city of Dubai has grown from a small coastal village to one of the largest urban areas in the Gulf. According to Government of Dubai statistics published in 2009 the Emirate had a population of approximately 1,770,000 people, with over 75 per cent (1,370,000) of residents being male.1 The gender imbalance results from the fact that many expatriate members of the male-dominated labour force do not earn the minimum salary necessary to obtain residence permits for their families, which was AE Dirham 10,000 (US$ 2,700) per month in late-2009.2 Data gathered by the Dubai Statistics Center in 2009 indicates that the majority of the Emirate’s expatriate males were employed in construction (48 per cent) and trading and repair services (12 per cent), while the majority of female expatriates were employed by families to perform household duties (34 per cent).3 Low wages among a significant part of the expatriate population has contributed to the extraordinary economic growth that supported expansion of the built environment during the first decade of the 21st century.

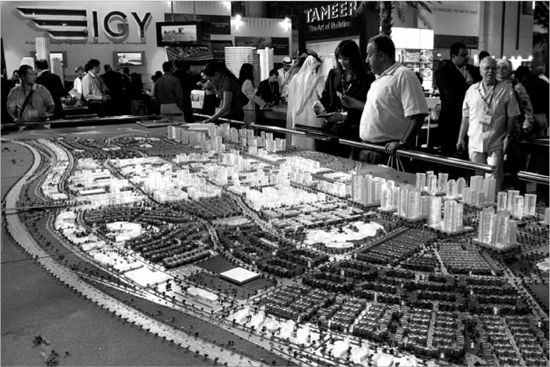

From the mid-1990s onwards, press releases heralded ever-larger projects presented through lifelike renderings that promised soft light, sea views and serenity. These renderings were necessary for indicating what a building was intended to become, but more importantly they represented the potential for exceptional returns in a real-estate market fuelled by off-plan sales and purchasing with the aim of reselling prior to the project even being completed. Man-made islands created a new coastline and almost instantly increased the supply of waterfront property. The developers of the Palm Jumeirah Island claim that this project alone expanded Dubai’s waterfront by 100 per cent, with the addition of 78 km of coastline. An extra 70 km could be provided by the aptly titled Waterfront scheme, which was purportedly designed for 1.5 million inhabitants. While it is unclear how the current global financial crisis will ultimately affect the project, the Waterfront’s developers have claimed that it ‘is on track to becoming the exemplar sustainable city founded on resource efficiency, social equity, and economic prosperity.’ Perhaps anticipating criticisms of this project, the developer’s statement succinctly addressed some of the negative effects of Dubai’s rapid growth while maintaining the promise of economic prosperity that could potentially attract 1.5 million people to live in the proposed scheme. This chapter takes the claims made by the Waterfront’s developers as a point of departure to discuss the complex interplay between political structure, economic conditions and architecture in Dubai. After providing a brief overview of the governance structure of the Dubai Emirate, I will consider how these political and economic forces have contributed to shaping the built environment, focussing specifically on challenges to sustainability-related measures and the complex issue of ‘identity’.

8.1 Male-dominated urban space in Dubai

8.2 Palm Jumeirah Island

GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE AND THE FOUNDATIONS FOR PROSPERITY

Dubai’s system of governance is autocratic; however, scholars often point to the neo-patrimonial aspects of the system that result in a hybrid web of bureaucratic state structures that are intermeshed with the patronage networks. Gero Erdmann and Ulf Engel have described neo-patrimonialism as:

… a mix of two types of political domination. It is a conjunction of patrimonial and legal-rational bureaucratic domination. The exercise of power in neopatrimonial regimes is erratic and incalculable, as opposed to the calculable and embedded exercise of power in universal rules (or, in Weber’s terms, abstrakter Regelhaftigkeit). Public norms under neopatrimonialism are formal and rational, but their social practice is often personal and informal. Finally, neopatrimonialism corresponds with authoritarian politics and a rent-seeking culture, whereas legal-rational domination relates to democracy and a market economy.4

Another important aspect of Dubai’s governance structure is the complex relationship between the public and private sectors. Martin Hvidt has addressed this in an analysis of the public/private ties as manifest in the autocratic and neo-patrimonial setting of Dubai. In autocratic and neo-patrimonial systems, the decision-making process remains centred on the ruler. But, because power must be legitimated, it results in what has been termed a ‘soft’ autocracy. Within democratic governance structures, the private sector relies on formal channels of interaction through state bureaucracies, whereas in autocratic and neo-patrimonial systems, the ruler is the sole decision-maker and exerts a significant influence over the private sector through patronage networks. However, in spite of the fact that the private sector does not have a formal means of participating in governance, it is not necessarily excluded from decision-making and influencing policy formulation. In the case of Dubai, Hvidt maintains that:

… the more the development strategy relies on the activities of the private sector, the more influence the actors of this sector will have in relation to policy formulation and decision-making. Furthermore, and as a corollary to this, it is assumed that the greater economic power of the private sector in relation to the ruler (the ruler – merchant power balance) the more influence the private sector will have in regard to decision-making.5

8.3 Dhows along the Dubai Creek

During the latter half of the 20thcentury a number of Gulf States depended on oil revenues to increase their prosperity. In contrast, Dubai’s relatively limited natural resources required that the Emirate concentrate on exploiting its established position within an interdependent trade network that extended across the Gulf region and beyond. Throughout the rise and decline of the pearl-diving industry and the increasing dependence on trading activity, Dubai relied heavily on foreign merchants. Michael Herb argues:

The merchants did not translate their economic power into institutions through which they could exert political control over the state. The merchants … did not have a parliament through which they could bargain with rulers over the raising and spending of taxes. Instead rulers levied the taxes and deputed their bodyguards to collect them; the merchants most effective tactic against the rulers’ exactions was that of capital anywhere–the threat of flight. Merchant bargaining power lay in the mobility of their trade (and of pearling) which allowed them to flee to a different shaykhdom if the rulers’ exactions grew too heavy. The position of a ruler, at least in the smaller Gulf state shaykhdoms, could not easily withstand a wholesale alienation of the merchant community, and rulers in any case had an interest in the prosperity of the merchant class.6

Strategic measures such as abolishing import and export tariffs to create a duty-free port during the early part of the 20th century, dredging the creek at the beginning of the 1960s to accommodate larger trading vessels, and the construction of container ports from the late-1960s onwards have made Dubai a primary hub for regional and global trade activity. Measures taken throughout the 20th century formed the foundation for diversification that ultimately contributed to attracting the significant foreign direct investment (FDI) to support the rapid expansion of the built environment during the ten-year period from 1998 to 2008. Data compiled by the Dubai Statistics Center indicates that FDI in Dubai totalled AED 42.5 billion (approximately US$ 11.6 billion) in 2006, which represented a 13.4 per cent increase over 2005.7 The sectors benefitting most were construction and financial intermediation/insurance (each accounting for approximately 35 per cent of the total FDI in 2006). European and non-Arab Asian countries combined were responsible for the largest share of FDI in Dubai in 2005 (82.7 per cent) and 2006 (86.2 per cent). And according to a report from the fDi Intelligence division of the Financial Times, ‘Dubai became the top destination city by number of FDI projects and capital investment, growing by an impressive 59 per cent and 122 per cent, respectively, between 2007 and 2008 and racing past Shanghai and London to take the top spot.’8

While the impressive inflow of foreign direct investment into Dubai resulted in rapid economic development and funded projects that may serve the city well in the future, the built environment has suffered from the lack of planning control and a narrow focus on short-term returns derived from real-estate investment. At the height of the speculative frenzy that drove development in Dubai, investors bought and sold off-plan projects at an alarming rate, pushing prices to levels considerably higher than the initial cost of the property. Although those attracted by immediate gain were keen to believe claims that Dubai was immune to boom-and-bust cycles, the global financial crisis from late-2008 proved otherwise. By late-August 2009, The Wall Street Journal reported that a number of distressed funds were preparing to purchase Dubai real-estate after values dropped 50 per cent in less than twelve months.9 In spite of this significant drop in values there has not yet been a rush of new potential buyers willing to invest in Dubai property; however, analysts suggest that if concrete actions are taken to improve transparency following the 2008 collapse, then capital may once again settle in Dubai due to its liberal economic policies and the progress made in providing public infrastructure and an urban rail system.

8.4 Dubai Metro

8.5 Park and commercial buildings near Dubai Creek

Autocratic rule, neo-patrimonial tendencies, and the intense reliance on the private sector have presented challenges, but these conditions have also contributed to Dubai’s success. Maintaining the delicate balance between public authorities and the private sector, and ensuring that FDI flows in (instead of out) to support growth in the Emirate, are strategies that influence decision-making, policy formulation and, as discussed later, the design and construction of the built environment.

CHALLENGES TO SUSTAINABILITY IN DUBAI

The desire to project an image of a ‘modern’ city complete with shimmering glass facades and grass-filled parks has significantly impacted the natural environment in Dubai. The ‘Living Planet Reports’ of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) have focused attention on the excessive use of resources in the UAE as a whole. According to reports issued since 2004, the ecological footprint for the country continues to remain the highest per capita in the world. Industry estimates indicate that 75–85 per cent of the total power generated during the summer season in the Gulf is used for air-conditioning, and cooling can cost as much as one-third of the total cost of the building over the lifetime of the structure. There has, however, been increasing recognition of the ecological challenges associated with architecture and planning in an environment characterized by intense climatic conditions and a scarcity of fresh water. The UAE Ministry of Environment & Water and the Environment Agency of Abu Dhabi revealed plans to address excessive consumption through the UAE Ecological Footprint Initiative, announced in conjunction with the publication of the Living Planet Report 2010.

In 2007 a resolution decreed that all residential and commercial buildings in Dubai must comply with a set of ‘green building’ specifications that would be effective from January 2008. No legislation had been enacted by the beginning of 2008, and in mid-August that year the Dubai Municipality held a conference in which it announced that along with the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) it would be developing an integrated ‘green building’ system for the city. But no regulations had appeared by the end of 2008, and on 24th January 2009 an article reported that these proposed ‘green building’ regulations would not be unveiled ‘for some time’.10 The article claimed that the delays could potentially be attributed to the global financial crisis and the resultant economic difficulties being faced by Dubai property developers.

The delays in developing comprehensive legislation that would result in sustainable approaches to building design and construction illustrate the complex nature of public/private relations in Dubai. While the governmental decree mentioned above recognizes that the long-term environmental impact of present practices cannot be sustained, the stringent measures necessary to regulate the building industry would almost certainly adversely affect short-term profit margins, and thus may jeopardize a reputation built upon neo-liberal economic policies and laissez-faire capitalism. Dubai’s reliance on FDI to fund its real estate and construction projects ultimately empowers the private sector, and results in concessions that negatively affect the built environment. Michael Herb has pointed out that the early-20th century merchants in the southern Gulf possessed bargaining power resulting from their ability to transfer their operations to a different sheikhdom if the rulers’ demands were deemed to be unfair. However, in the early-21st century, capital is infinitely more mobile, and advanced communication technology ensures that funds can be easily transferred across the globe in minutes. In neo-patrimonial systems this mobility of capital has significant consequences that fundamentally affect the power balance between public and private entities and, because of the influence that can be exerted on aspects such as the development of sustainability measures, it ultimately shapes the built environment.

Dubai’s authorities have announced a series of initiatives to reduce energy and water usage, including the introduction of a revised tariff structure known as the ‘slab system’ in March 2008. This system charges users for electricity and water using a sliding scale: the greater the consumption, the higher the tariff. According to news reports, those who failed to implement energy- and water-saving measures after the first year would have seen cost increases of up to 66 per cent.11 In spite of this, DEWA reported a rise in peak demand from 4,736 MW in 2007 to 5,287 MW in 2008.12 Perhaps this was due to the fact that the tariff affected only those with high consumption levels, and the system had been structured to ensure that approximately 80 per cent of consumers would not be subject to increased costs. In addition, the homes or farms owned by UAE citizens were exempted from the ‘slab system’.13

Although these preliminary measures have been taken, energy costs remain low and there is little incentive for fundamental change in building design and construction. While one may argue that laissez-faire economic policies and ecological sustainability are not mutually exclusive, the current situation in Dubai indicates that direct intervention may be required to balance the desire for profit with the urgent need to reduce the consumption of resources and environmental degradation. Long-term sustainability will depend on comprehensive measures and widespread implementation. The cases of the ‘green building’ legislation and the ‘slab system’ illustrate the impediments associated with implementing stringent sustainability measures within a neo-patrimonial system. In both cases the concessions made to private sector interests and the expatriate community ensured that the costs of doing business remain low, which encourages existing investment to remain and attracts new FDI. Additionally, measures like excluding the residential or farm properties of UAE citizens from the slab system seek to establish political legitimacy through benefactions that bestow favour upon citizens. Architects and planners may possess the knowledge to address issues related to sustainability, but design strategies and construction technology may prove less important than political solutions that seek to balance private interests and the ‘public good’.

THE IDENTITY DEBATE

It is difficult to specifically define what is meant by ‘identity’. Marxist conceptions of class consciousness, Émile Durkheim’s notion of collective consciousness, and Ferdinand Tönnies’ category of Gemeinschaft have provided the foundations for thinking about collective identity, focusing on what are believed to be ‘essential’ characteristics of a unified social experience that binds individuals together through commonalities. While Durkheim’s work concentrated on the cultural construction of reality, later social constructionist approaches have rejected any essentializing tendencies, maintaining instead that those aspects that characterize a collective group are socially constructed through the interaction and agreement of individuals. Post-structuralist thinkers have insisted on the relative nature of the notion of identity, emphasizing its multiple, shifting, and fragmented character, and arguing that processes of identity formation are ambiguous and unstable.

8.6 Urban space near to the Dubai Mall

The question of identity in the built environment is equally complex, although it is often reduced to issues related to the visual appearance of a building or urban area. Some argue that new urban areas in Dubai cannot be distinguished from those found in other rapidly developing cities throughout the world. In an essay entitled ‘In What Style Should Dubai Build?’, I considered how the speed, scale and variety of architectural production induced anxiety of the sort that had motivated the 19th-century German architect, Heinrich Hübsch, to pose the question In What Style Should We Build?14 Answering Hübsch’s question within the context of Dubai presents challenges, however, because it involves the use of ‘we’, implying communality and the potential for consensus regarding a singular ‘style’ of buildings that would reflect and respond to the diverse population in the Emirate. Although the marketing material produced by Dubai-based developers often claim the creation of ‘communities’, it is questionable whether shared norms and values will emerge and lead to the development of public institutions within an autocratic system (see Plate 13).

Currently, UAE citizens comprise less than 20 per cent of the population of Dubai, and some projections made prior to the current global financial crisis indicated that the proportion could shrink to 5 per cent. The tensions resulting from an increasing expatriate population are summarized in a quote that appeared in a 2007 Gulf News article: ‘The issue is we are losing our identity. The national identity is about to get lost because of foreigners … If we focus on westernization we will lose everything.’15 In presumably a response to the growing concern among Emiratis over this issue, the UAE Ministry of Culture, Youth and Community Development organized a ‘National Identity’ conference in April 2008 to consider the consequences of the demographic imbalance between citizens and what is an extremely diverse expatriate population. And in a debate regarding appropriate dress within Dubai’s shopping malls, a UAE citizen was quoted in the Gulf News as saying: ‘I don’t want to generalise and say that all expats behave in that inappropriate way. However, certainly many expats who come to our country are either not aware of our cultural norms or are just not respectful of them and choose to behave any way they want to.’16 An expatriate from a neighbouring country presented an alternative viewpoint: ‘I love Dubai and I like its style. But the way I dress is completely a personal matter and I don’t allow anybody to educate me on what to wear and what not to wear.’17 While the few individuals interviewed for the Gulf News article may not necessarily be representative of the opinions and attitudes of the larger population, the views expressed are indicative of the tensions that exist.

The fact that a shopping mall happens to be the site within which tensions between Dubai’s diverse populations become manifest warrants further consideration. Dubai’s larger shopping malls are typologically equivalent to those of a similar scale found elsewhere throughout the world. Hypermarkets from Europe and Asia, jewellery stores selling Swiss watches, electronics stores offering the latest in mobile phones, and food courts with restaurants serving everything from fatoosh to French fries reveal the increasing standardization of global consumption patterns. The architecture of the Dubai shopping malls provides little more than superficial nods to the context; however, by observing the variety of clothing worn by shoppers, one can perhaps deduce that they are in one of the Gulf states where those who outwardly express a sense of modesty mingle among others who appear to be dressed for a day at the beach. In the case of recommended dress codes for shoppers, the privatized space of the mall becomes the site within which the public can test the limits of tolerance and contest context-specific norms.

8.7 Mall of the Emirates

Maintaining a balance between a relatively small group of Emirati citizens, a large expatriate work force, and transient tourists compounds the difficulties associated with defining the role of identity. In addition, the right of residency in Dubai is based on employability and the right to work (and therefore the right to remain in the country), and is not extended to expatriates past the age of 70 years old.18 Although developers have marketed residential projects based on the fact that a life-long visa would come with a freehold purchase, in mid-2008 the Dubai Real Estate Regulatory Agency stated unequivocally: ‘There is no direct link between property ownership and residence visas. Developers should not lure investors to property sector with a promise of residence visa.’19 And in 2009 the Dubai Naturalisation and Residency Department issued a statement saying that residents who own property in the UAE but are not employed there will be required to leave the country every six months, and their visa would then be renewed as they re-entered Dubai at the airport.20 This legislation was later revised and is now assumed to allow a three-year residency visa for those owning property with a value of at least AE Dirham 1 million. The lack of clarity and consistency and the legal constraints on establishing long-term residency will continue to have an effect on the built environment. Although the present financial crisis may curb off-plan sales and lead to legislation that restricts the practice of buying and selling before completion, architects will continue to face the challenges associated with designing for a population that is both extremely diverse and largely transient.

8.8 Typical suburban villas in Dubai

Faced with such uncertainty, many architects have imported pre-existing models from elsewhere, or resorted to reproducing ‘traditional’ architecture, or concentrated on developing an iconic formal language. Perhaps the most ubiquitous case of imported models has been the transplantation of North American suburban settlement patterns, resulting in houses designed as detached free-standing dwellings located in the centre of relatively large plots of land. George Shiber described a situation in Kuwait in the 1960s, which has since been repeated in residential neighbourhoods throughout Dubai as well:

… the modern house or “villa” plunked on a uniform and non-descript plot which, with several hundred similar plots constitute the inorganic and uneconomic new neighborhoods of Kuwait, is often a caricature house in a caricature setting obeying a caricature philosophy of architecture and urban form that could have only emanated from caricature architectural concepts. The house sits clumsily in its plot exposed on all four sides to the elements, with a garden that is no garden at all for it consists of the “corridor” set-backs from every boundary of the lot.21

The Madinat Jumeirah hotel resort and mall represents one of the prime examples of reproducing what is believed to be the past (see Plate 14). The resort complex is described by its owners as ‘a magnificent tribute to Dubai’s heritage and is styled to resemble an ancient Arabian citadel’. It is unclear which particular ‘Arabian citadels’ informed the design of the complex, and there is little beyond the façade treatment and non-functional wind towers that makes reference to ‘Dubai’s heritage’. The following statement made by the architects reveals that the basis for their design was not necessarily actual architecture from the past, but the result of imagining what might have been:

What if in ancient UAE or ancient Oman they had the money we have now and the technology we have now? What would they have built? That’s how we came up with Madinat Jumeirah. We built what they might have built with the resources available to us.22

8.9 Madinat Jumeirah hotel resort and mall

The interpretative freedom that is evident in the admission that the designers ‘built what they might have built with the resources available to us’ reveals the wholesale negation of the complex relation between time and place. Although it was perhaps unintended, the statement also presupposes that architecture is reducible to stable stylistic tendencies and determined by money and technology.

While developments like the Madinat Jumeirah have been constructed as an assemblage of iconic elements derived from an imagined past, others have treated buildings as singular iconic statements. A survey of 20th-century architecture in Dubai certainly reveals a steady progression toward the iconic.23 This has had a significant effect on the built environment, and has resulted in an emphasis on the image of singular buildings. Projects like the Palm Jumeirah and The World islands are massive manifestations of the iconic at an urban scale. The speculation that supports growth in the real-estate and construction industries demands investors and their money, which, in turn, requires visually arresting icons that attract attention. In Dubai and neighbouring Emirates, many real-estate transactions were based on little more than visual representations in sales brochures and elaborate models. The material reality has been less important than the reality constructed by photorealistic images; the craft of making – often absent in the final building itself – was replaced by the artifice of well-trained CAD technicians.24

While the speculative real-estate market supports economic growth in Dubai, it also raises questions of a political nature as the aim is to sell residential buildings that owners will ultimately expect to inhabit. Statistics provided by Dubai’s Real Estate Regulatory Agency indicate that, since 1973, Indian nationals have been the largest group of expatriates involved in land transactions in Dubai (AED 18.7 billion); they has been followed by citizens of the United Kingdom (AED 17.3 billion), Pakistan (AED 10.4 billion), Iran (AED 8.4 billion), Saudi Arabia (AED 7.8 billion) and the Russian Federation (AED 5.5 billion).25 At least prior to the start of the financial crisis in late-2008, the majority of buyers were foreign investors – some companies saw this as a positive advantage, and liberally interpreted the statistics to market their properties. One company wrote:

8.10 ‘Cityscape Dubai’ real-estate and development trade fair

8.11 Residential development along Jumeirah Beach

In Dubai the majority of the population herald from abroad, up to 94 per cent of the entire population are expatriates and the number of those coming to the emirate grows substantially on a weekly basis as up to 20 new companies establish themselves in the emirate each week. This trend is projected to continue for at least the next five years as the remaining planned 7 free trade zones move from the planning stages into realisation and more opportunity is created in Dubai for international companies from around the world.26

If one maintains that the built environment should respond to and reflect its inhabitants, then the situation in Dubai presents complex challenges. Ultimately, Emirati citizens who form part of a shrinking minority, and the expatriate population comprising the majority, may have substantially different needs and competing interests. Diversity within the citizen population and among the various expatriate groups further compounds the challenges. To say that architecture and planning should serve all groups could result in universalizing tendencies that may deny the cultural differences present within the heterogeneous population, and which has enriched and made substantial contributions to the growth of Dubai. And, as the debate regarding appropriate dress within Dubai’s shopping malls proves, the negation of difference would certainly prove problematic. Attracting FDI after the current global recession will require that vaguely defined property ownership legislation be clarified. Stable and more inclusive residency policies may foster a sense of belonging and encourage the substantial expatriate population to identify with, and contribute to, improving the built environment. However, as is indicated by the long delays and contradictory messages that have characterized the process of developing clear rules on such issues, the desire to attract investment is tempered by the need to address the concerns of the Emirati citizen by imposing restrictive visa regulations for expatriates who purchase property. But if non-citizens do not view Dubai as home, it is likely that buildings will continue to be treated as mere commodities to be considered as investments with no value beyond the market price.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

According to the Dubai Strategic Plan 2015, development will be guided by the adoption of free-market economic principles and the following initiatives: a unique relationship and partnership with the private sector; the protection of the national identity, culture and way of life; an openness to the world while maintaining uniqueness; providing a world-class infrastructure to suit the requirements of all users; and preserving the environment in line with international standards.27

8.12 International City development

Reflecting some of the neo-patrimonial aspects of Dubai’s governance structure, the initiatives also reveal some of the inherent challenges that the Emirate faces. Balancing free-market principles and the informal power of the private sector with protecting ‘national identity’ and preserving the environment may prove incredibly difficult, even within an autocratic system. As discussed above, the specific political and economic forces that have developed and transformed over time continue to condition Dubai’s built environment. Trading activity and the Emirate’s increasing reliance on merchants during the 20th century resulted in private sector influence on policy formulation and decision-making. And this influence seems to have increased with the efforts to attract FDI, and the measures now being taken to ensure that investors remain confident in Dubai’s ability to manage the substantial debt that was amassed to fund its decade-long building boom.

8.13 Burj Al Aarb

Until late-2008, these rapid inflows of FDI were hastily converted into new urban quarters and iconic architectural statements. Announcements of cancelled projects were quickly followed by statements claiming that a respite from the rush to build would result in more considered approaches to the built environment. Nevertheless, as the case of sustainability legislation discussed above indicates, the influence of the private sector and the necessity to ensure that capital does not flow outward may hinder efforts to implement measures that would improve the quality of design and construction. Now that Dubai’s economy and building activity has begun to pick up again after the financial crash that started in 2008, these urban tensions may resurface. Estimates suggest that Dubai’s population has continued to rise, such that it is now probably around 1,900,000, and with the same demographic features noted earlier.

8.14 Burj Dubai and Business Bay development

Critics that hastily conclude that ‘Dubai has no identity!’ also tend toward superficial pronouncements that focus solely on instances of iconic form-making and the isolated enclaves resulting from an emphasis on large-scale projects such as the offshore islands. Dubai’s built environment in fact grows out of the tensions resulting from embracing free-market principles, balancing the demands of a minority Emirati population while attracting foreign investment (as well as a foreign labour force to translate this finance into buildings, goods and services), and managing a web of bureaucratic structures intermeshed with patronage networks. These tensions make Dubai what it is, and they will continue playing a role in determining what it will become.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sara Kasa made significant contributions to this essay through editorial comments and research assistance.

NOTES

1 Dubai Statistics Center, Dubai in Figures 2009 (Dubai: Government of Dubai, 2009), p. 4.

2 Abdullah Rasheed, ‘Salary norm for family visas to be revised’, Gulf News website, http://www.archive.gulfnews.com/nation/Immigration_and_Visas/10327894.html (accessed 1 July 2009).

3 Dubai Statistics Center, ‘Employed (15 Years and Over) by Nationality, Sex and Economic Activity – Emirate of Dubai (2009)’, Table (02-05), http://www.dsc.gov.ae/Reports/DSC_LFS_2009_02_05.pdf (accessed 15 September 2011).

4 Gero Erdmann & Ulf Engel, ‘Neopatrimonialism Revisited – Beyond a Catch-All Concept’, GIGA-WP-16/2006, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA) Working Papers Series, Hamburg (2006), p. 31.

5 Martin Hvidt, ‘Governance in Dubai: The Emergence of Political and Economic Ties between the Public and Private Sector’, Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies Working Paper No. 6, Centre for Contemporary Middle East Studies, University of Southern Denmark (June 2006), p. 5.

6 Michael Herb, All in the Family: Absolutism, Revolution, and Democracy in the Middle Eastern Monarchies (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999), pp. 57–58.

7 Dubai Statistics Center, ‘Bulletin: Foreign Direct Investment – Dubai Emirate 2007’ (Dubai: Government of Dubai, 2007), p. 1.

8 ‘“Asian Attraction”, The Shape of Things to Come: The FDI Outlook for 2009 and Performance Analysis for 2008’, Financial Times fDi Intelligence Report (April/May 2009), p. 9.

9 Stefania Bianchi, ‘Funds Prowl Dubai Properties Investors’ Interest After Price Tumble Could Revive Market’, The Wall Street Journal website, 12 August 2009, http://online.wsj.com (accessed 12 August 2009).

10 Jamie Stewart, ‘DM Delays Green Regulations to Aid Troubled Developers’, Arabian Business.com website, http://www.arabianbusiness.com/544381-dm-delays-green-regulations-to-aid-troubled-developers (accessed 28 January 2009).

11 Roxane McMeeken, ‘Soaring electricity costs hit Dubai’, Building website, http://www.building.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=3135161 (accessed 5 March 2009).

12 Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA), http://www.dewa.gov.ae/aboutus/electStats2008.aspx (accessed 10 August 2009).

13 ‘DEWA Restructures Tariff for More Responsible Electricity and Water Consumption’, Eye of Dubai website, http://www.eyeofdubai.com/v1/news/newsdetail-18501.htm (accessed 25 February 2008).

14 Kevin Mitchell, ‘In What Style Should Dubai Build?’, in Elisabeth Blum & Peter Neitzke (eds), Dubai: Stadt aus dem Nichts (Basel: Birkhauser, 2009), pp. 130–140.

15 Reema Saffarini, ‘How does my City Grow?’, Gulf News website, http://archive.gulfnews.com/articles/07/06/16/10132864.html (accessed 12 September 2009).

16 Fatma Salem, ‘Dubai malls join anti-indecency campaign’, 8 August 2009, Gulf News website http://www.gulfnews.com/nation/Society/10338386.html (accessed 8 August 2009).

17 Ibid.

18 Procedure Manual for Ministry of Labour United Arab Emirates, Version 2.6B, MENA Business Services.

19 Bassma Al Jandaly, ‘No automatic residency for property buyers in Dubai’, Gulf News website http://www.gulfnews.com/business/Real_Estate_Property/10223351.html (accessed 25 June 2008).

20 Martin Corucher, ‘UAE property owners must exit to renew visa’, KhaleejTimes, 4 August 2009.

21 Saba George Shiber, The Kuwait Urbanization: Being an urbanistic case-study of developing country (Kuwait: Kuwait Government Printing Office, 1964), pp. 287–288.

22 ‘Brand New Old’, Identity (July/August 2004), p. 86.

23 Kevin Mitchell, ‘From the intimate to the iconic: Architecture in Dubai from 1967 to 1997’, in George Katodrytis (ed.), Dubai: Growing through Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, in press).

24 Kevin Mitchell, ‘Speculations on the Future Promise of Architecture in Dubai’, in Ahmed Kanna (ed.), The Superlative City: Dubai and the Urban Condition in the Early Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), pp. 149–166.

25 Real Estate Regulatory website, http://www.rpdubai.com (accessed 9 September 2009).

26 Clifton website, http://www.clifton-dubai.com/working_in_dubai.html (accessed 2 July 2008).

27 Government of Dubai, Dubai Strategic Plan 2015, http://egov.dubai.ae/opt/CMSContent/Active/CORP/en/Documents/DSPE.pdf (accessed 1 August 2009).

9 In Manama, Bahrain, continuous land reclamation is changing the urban morphology at an unprecedented pace, here showing the northern coastline from the BFH Tower to the Al Seef district in the distance

10 The Msheireb project in Doha, Qatar, by AECOM/Arup/Allies and Morrison

11 The coastline of Abu Dhabi, UAE, as seen from on high

12 Grand Mosque (Sheikh Zayed Mosque) in Abu Dhabi, UAE

13 ‘Cityscape Dubai’ real-estate and development trade fair

14 Wind-tower motifs at the Madinat Jumeirah in Dubai, UAE, with the Burj Al Arab Hotel beyond

15 ‘Chinese’ section of the Ibn Battuta Mall in Dubai, UAE

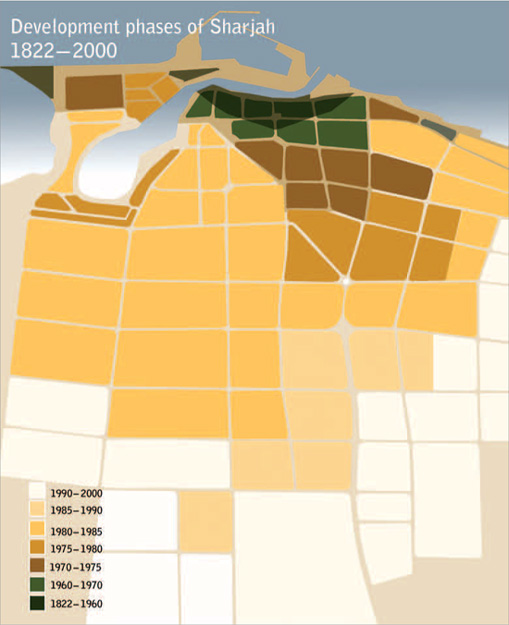

16 Development phases of Sharjah, UAE, from 1822-2000