8

EARTH OR WORLD?

Aerial image and the prosthetic imagination

Lawrence Bird

The image is one mode by which architecture appeals to us. The image has long been bound to the conditions of architecture’s creation, its presence and its performance. But images today are fraught. They easily become commodities, objects of exchange, fetishes substituted for what they ostensibly present to us. They are increasingly swept up in a rapid, international traffic in which each image is devalued in the sense Walter Benjamin articulated as early as the 1920s.1

That trade is made possible by technical frameworks such as media technologies and infrastructures. It seems obvious to understand such systems as instances of what Heidegger referred to as the gestell: the technical enframing of human life. There is nothing, however, obvious about the essay from which Heidegger’s term is drawn, “The Question Concerning Technology.” Referring to technological enframing, Heidegger cites Hölderlin’s poem Patmos:

Heidegger suggests that just as art is not about aesthetics, so the essence of technology is nothing merely technological. For Bernard Stiegler, this means that gestell is not simply about instrumentalization or the achievement of an end. Instead it stems from and is one aspect of the unfolding of our humanity. In this essay, I will draw on Stiegler’s reading of Heidegger to consider images harvested from Google Earth, probably the most ubiquitous imaging resource available today. My intention is to address the following questions: Is the devaluation of the image, its reduction to a mere product – and the corollary of that process, the impoverishment of our ability to compel and enchant – inevitable? Or is there evidence from within the territory of the technologized image that some kind of redemption might be found there – that in some sense a saving power grows where danger is?

Rendering image

Heidegger made a distinction between the conditions of “earth” and “world.” The former was considered as a bare well of material, and the latter as that material gathered, shaped, and rendered meaningful through our work. The technological system discussed in this paper perhaps unintentionally acknowledges that distinction in its very name: Google Earth. This online mapping resource is the most accessible and widespread of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Earth presents for public consumption an exhaustive documentation of global geography and inhabited space. As such, it seems to fulfill one of the promises of the Enlightenment: a complete and seamless mapping of the world, a mapping made possible through the triumph of technology. Charles Waldheim has used the term “representational domestication” to describe the modern aerial image’s reduction of the landscape to an object of surveillance, control, and consumption.3 Google Earth’s most ambitious attempt to fulfill that project would seem to deny any possibility of imaginative consideration of our being in the world. But that is not the case. The work of several artists, including Doug Rickard, Jon Rafman, Edward Burtynsky and Mischka Henner, suggests that one can find in those images the potential for interpretation and criticism.4

The work I present below, while dovetailing with such explorations, has a different focus: it considers the rifts that appear within digital images themselves as a result of their technologization. This chapter is a first attempt to tease out the anomalies in such systems, and to think about what they might mean for those who, like architects, try to make earths into worlds. The images I will look at are those of the landscape of the Canadian prairies, where I currently make my home. There has long been a resonance between our technological manipulation of that landscape and our manipulation of the image generally. One irony in the history of electronic imaging is that the first all-electronic television drew on an agricultural precedent. The so-called “image dissector” of the 1920s was inspired by the realization of a farm boy that the movement of one man, a horse and a plow across the landscape inscribed a pattern on the surface of the earth. That epiphany provided the principle for the electronic conversion of images (two-dimensional) into signals (one-dimensional) and back again.5 The term “image dissection” can describe just as well our digitization of images today, their decomposition into pixels and ultimately bits. Progressive scans across a flat surface, each pass harvesting or sowing another fragment of image, are still the basis of most digital displays. The discussion that follows will demonstrate that this resonance between our modern management of the earth and our manipulation of its image runs quite deep.

Not mere instruments

Rather, as Stiegler asserts, such forms of technical manipulation matter profoundly to our condition as human beings.6 He insists that our humanity is, and has always been, negotiated with technical objects and processes outside of ourselves. Mankind is in fact defined by the use of tools, that is, of prosthetics. Drawing on anthropological sources, Stiegler argues that human beings are engaged in an instrumental maieutic.7 By this he means an interplay in which our creation of tools in anticipation of need on the one hand, and the formation of human cognition in response to this creation on the other, results in a drawing forth of the human being. Our works create the conditions that surround our own development. Today’s mechanized planet is only the latest manifestation of this phenomenon. What might be different now is that our prosthetics today can seem all-encompassing. Google Earth’s ostensibly complete mapping is a graphic demonstration of that.

In the circumstances Stiegler describes, it is meaningless to imagine a condition of man’s original independence, in which he did not always lack something whose substitution through technics he anticipated. Instead, lack becomes man’s very definition and, therefore, his fulfillment. Today we experience this as the circumstance in which our actualization is the same thing as our derealization. This is not a post-human but an acutely human condition. It binds us with complex technical prosthetics existing somewhere between the conditions of living and non-living objects. Stiegler proposes that these constitute in fact, after the two genres of animate and inanimate beings, a third kind: organized inorganic beings. These, like us, demonstrate perfectibility and a movement toward complexity and indeterminateness. It doesn’t need to be pointed out to us that this genre of being can include architecture and landscape architecture.

Stiegler warns of, or heralds, the contemporary manifestation of this condition with his words describing a modern man’s “disappearance in the movement of a becoming that is no longer his own.”8 We move forward into the future not alone but accompanied by technical creations, which are other than us, part of us yet alien. This is Stiegler’s understanding of Heidegger’s saving danger. In this condition we cease to be merely the designers of our works but instead become their operators, or perhaps more precisely their stalkers. We follow along in wake of our work, as the farmer behind the plow. This is my condition as I navigate Google Earth, harvesting images in which I find meaning.

Before we turn to the evidence we might glean directly from those images, we need to understand that Google Earth forms one specific type of prosthetic complex: a prosthetics of perception. In allowing us to see, and perhaps even to begin to act, on the other side of the world, it obviously extends our own sight to incorporate the mechanical eye of a satellite. So doing, it extends our body there too. Maurice Merleau-Ponty briefly addresses prosthetic perception in the Phenomenology of Perception, where he makes that case that the edge of the body is not merely our physical boundary, our skin. Rather, it lies beyond us, where we act; or even as far as the eye can see.9 As he explains:

The blind man’s stick has ceased to be an object for him, and is no longer perceived for itself; its point has become an area of sensitivity, extending the scope and active radius of touch, and providing a parallel to sight…. To get used to a hat, a car or a stick is to be transplanted into them, or conversely, to incorporate them into the bulk of our own body.10

While these words are often interpreted as referring to physical extensions of the body, a kind of materialization of sight, the point is that the realms of visual perception and hapticity bleed into each other as we incorporate devices into our perceptive apparatus. Merleau-Ponty himself, in his later writing, imagined the incorporation of even the new information technologies into this understanding of perception. In 1959 he wrote the following working notes in anticipation of the task he saw for himself with regard to this area of knowledge:

Show …

that information theory applied to perception, and operationalism applied to behaviour – is in fact, confusedly glimpsed at, the idea of meaning as a view of the organism, the idea of the flesh …

that the perception-message analogy (coding and decoding) is valid, but on the condition that one discerns a) the flesh beneath the discriminating behaviours b) speech and its ‘comprehensible’ diacritical systems beneath the information.11

In other words, the processes of coding and decoding imply their own kind of chiasm. Merleau-Ponty’s mention of speech here is worth putting in context. In The Visible and the Invisible, as though in anticipation of the work others were later to pursue in semiotics, Merleau-Ponty made the first forays into territory he would be not have time to fully explore himself. He asserted that the relationship between signs and things is an analogue of the subject/object relationship: “As there is a reversibility of the seeing and the visible, and as at the point where the two metamorphoses cross perception is born, so also there is a reversibility of the speech and what it signifies….”12 These lines suggest that even signal and informatic response, on which the operation of a computer is based, as well as sign and signified (and in the case we are examining here, earth to its image), imply a condition of flesh in Merleau-Ponty’s terms. Thus perhaps it is not incidental that Google Earth has built into its interface a kinesthetic response: we don’t merely see, we fly like bodies through the air, we accelerate and decelerate as though we had mass. While seeming to take us out of our own bodies, this tool also paradoxically drags them along with us to the other side of the world. As we will see, rather than distancing us from images through vision, it implicitly embeds us in images and in the landscape they represent. This is far from a Cartesian space, but to be convinced of this we have to find evidence within the phenomenon itself.

A pixilated prairie

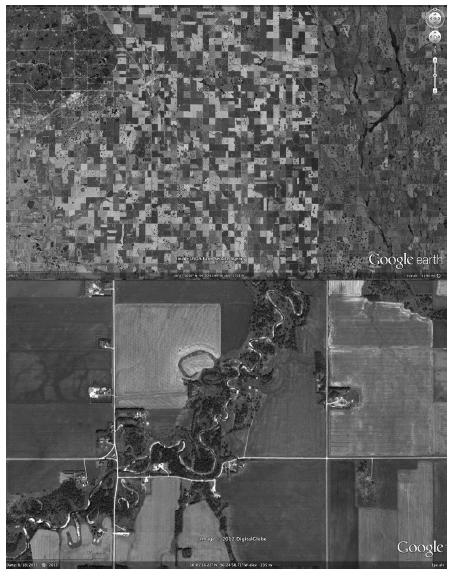

The upper half of Figure 8.1 shows the prairie landscape as viewed in Google Earth. The square-mile grid of prairie fields on display here is a result of modern systems of demarcating the world, dividing and owning land, and growing and distributing crops. This system for organizing the prairie dates from the nineteenth century, but it has a strange resonance with today’s imaging technologies. On seeing these images, we might even say that the prairie surface seems pixilated. In fact, it is. A pixel is a picture element, a component of a whole image broken down into cells of identical size (generally consistent and organized by a grid within a given image) and with a single defined color. Complex, rich, and whole images are broken down into minimal elements manageable by a digital infrastructure. The same is true of the contemporary prairie. Native plants are replaced by domesticated, monocultural and genetically modified crops. Laid out in a grid of exactly one mile square, these cells render crops up to transportation networks, which carry the crops to markets across the globe. Both the imaging systems and agricultural systems, in Heidegger’s terms, expedite their object, by unlocking it, exposing it, and directing it toward an end. It is perhaps no surprise to see this strange congruence between the treatment of the landscape and the treatment of its image made so apparent in an environment like Google Earth, where two parallel systems for reduction of things – landscapes on the one hand and images on the other – to mere objects confront and map onto each other.

Figure 8.1 Aerial views of prairie landscape: upper image, courtesy Google Earth, USDA Farm Service Agency; lower image courtesy Google Earth, © 2012 Digital Globe

But the prairie landscape resists total instrumentalization. The lower half of Figure 8.1 displays a tangle of loops, oxbows, and curves that disrupt the grid. These disruptions demonstrate the effect of water undermining the agricultural grid. This disruption is not only spatial but also temporal: the riparian tangle represents a time frame of seasonal and episodically cataclysmic cycles. Every few years, thousands of square miles of farmland are inundated by floods. Over time the course of rivers alters dramatically, snaking across the landscape in an ever-changing evolution, and leaving the traces of past inundations and watercourses as rifts in the grid. This process occurs over cycles of time of long and short duration, in contrast to the grid, which aspires to act “out of time,” trying but failing to preserve one pattern forever.

We might note in these images a simple dichotomy between artificial and natural, and as designers we might find inspiration in the wet and cyclical processes that oppose the hard and straight edge of the grid. That might imply a similarly curvaceous, liquid, or perhaps even gaseous architecture, one that escapes all controls. But dichotomies like this are too simple. Things are more complicated than that today.

Time and disruption

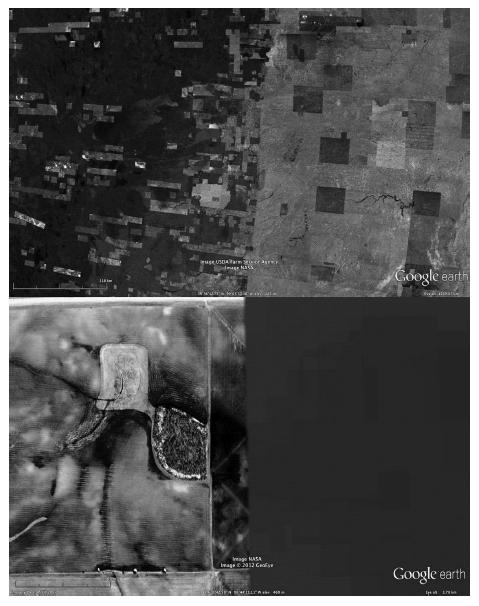

Media resources – from components of a computer, to digital networks – have their own relationships to time, which cannot be reduced to a simple modern rationalization of the flow of life. Media-based objects are created in time (almost “just in time” – they do not exist until rendered active by a central processing unit); they can evolve over time (like a wiki). They carry information which is potentially eternal, but which can decay over time with their media substrate (disk or tape), or can be zeroed-out in an instant. Media systems all have clocks, and record their activity over time in logs and archives. Google Earth can be understood as one such archive, and one that records not just changes in the physical environment but also developments in the imaging systems recording that environment. Google Earth’s Time Slider function, for example, reveals the evolving resolutions and extents of aerial imagery taken in different years. An example of this shift appears at the top of Figure 8.2. Because different places came under the eye of a satellite at different points in recent history, the mapping of the prairie landscape is uneven.

These various engagements with time are instances of that paradoxical complexity and indeterminacy that Stiegler asserted are characteristic of complex technical systems. The last mentioned – digital archives – can be understood as instances of what he refers to as the intertwining of anthropogenesis and technogenesis, in which human memory is displaced into an epiphylogenetic history, a historical record outside of our species. This is central to his thesis that technics is time: that our historical becoming is inseparable from our engagement with technical instruments. In the case of the Google Earth’s archive of time, this history and the disparities of image reflecting it can involve disparities in technological development, in financial or political power, in the relationship of the territory to those controlling the imaging system and those curating its content.13 In the upper half of Figure 8.2, for example, the most notable feature is the border between the United States and Canada (north is to the left). The origins of such anomalies are complex; my interest here is in the fact that they exist at all, that this epiphylogenetic history is lumpy and uneven, shot through with contradictions and disparities.

Figure 8.2 Aerial views of prairie landscape, near US/Canada border: upper image, courtesy Google Earth, USDA Farm Service Agency and NASA; lower image courtesy Google Earth and NASA, © 2012 GeoEye

One such disparity can be seen in the lower half of Figure 8.2, a detail of the upper image.14 On the left side of Figure 8.2, a plowed field displays the furrows left by agricultural machinery as its operator negotiates between the square-mile grid and the natural processes and emergent forms native to the prairie. We recognize in it a specific and concrete landscape, a landscape marked by the working of the plow. This is one kind of technical engagement with the earth. To the right of the same image we can see a field of another kind: a portion of a satellite tile, one of much lower resolution than the source of the image to the left. This is another form of technical engagement with the earth. In it we can read a different prairie: a digital field that stands as landscape in its own right, with its own boundaries, topography, areas of density and intensity. We know – we recognize this in its array of brown and green digital artifacts – that this landscape has been created by a complex system of mechanical and electronic devices. This apparatus of prosthetic perception is visibly imperfect. Perceiving these two fields we are, perhaps despite ourselves, both compelled and discomfited by their juxtaposition, by their simultaneous foreignness from yet assimilation to each other. In light of Stiegler’s and Merleau-Ponty’s arguments, that resonance is comprehensible. This is a prosthetic perception entangled with a complex and non-linear (and politically-inflected) engagement of time. It implies a reversibility of landscape and image in which distinct but related forms of plowing and harvest can be understood as one flesh, if a flesh divided. If architecture can be seen as an analogous working of the land (and materials), this might imply an engagement of its image, and distortions of that image, in the creative process as one means of transcending the purely utilitarian condition of building.

Seams in the map

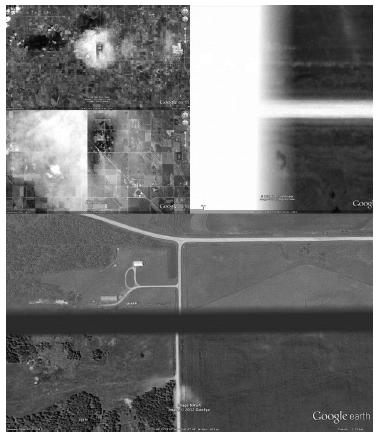

At times the temporal displacement between images can be just a matter of hours, and this can be enough to disrupt a homogeneous reading of geographic space. In Figure 8.3 we see two examples of this. In the upper half of the image, a succession of zooms draws us into the edge between two satellite tiles. Each of these images is spliced together by Google’s machinery from two tiles. One of these was captured while a cloud overlaid the prairie town of Stonewall; the other was captured after the cloud had moved on. We perceive in one image two contradictory worlds: both an opaque white cloud, and the clearly seen prairie. As one continues to zoom in, the line between the two worlds fluctuates between the sharpness of a knife and the indeterminacy of fog. If one continues until just before the image transforms into Street View, the whiteness of the cloud generates a hieroglyph-like display of artifacts: has the image been transformed into text? On what hidden code have we stumbled as we wander through this fog? What script has begun to be played out here? The fusion of two times has created a heterogeneous space whose artifacts seem to speak, if accidentally, of conditions at the heart of the digital generation of images. Other displacements and accidents provoke similar speculation. We see one of these in the lower half of Figure 8.3. In this image the line between satellite tiles takes on its own material and spatial qualities, becoming an opaque swath between the beginning and end of a road. What shifts and displacements does this anomaly imply? What, might we imagine, lies in the shrouded space between upper and lower images? What occurs out of sight along the road between them, shifted just slightly to one side somewhere along the way?

Figure 8.3 Aerial views of prairie landscape, environs of Stonewall, Manitoba: upper images, courtesy Google Earth, © Cnes/Spot Image and Digital Globe; lower image courtesy Google Earth and NASA, © 2012 GeoEye

These images provoke a kind of narrative interpretation, introducing the potential for fiction and imagination into an ostensibly objective documentation of geography. If, as Paul Ricoeur has claimed, narrative is what sews up the rifts opened up within us by our experience of time, we might see in these images a narrative force provoked by the gaps in Stiegler’s epiphylogenetic history, the record of time captured and created in part through technical devices.15 These devices seem to struggle and fail alongside us in our impossible attempt to process temporal experience. Out of this failure emerge the rifts in heterogeneous invented spaces into which we can imagine stories. The fictive dimension of representation confirmed by these images –that all images have a narrative aspect, that no image is precisely what it pretends to represent, that all involve transformation of the real rather than its straightforward representation – seems here to implicate time, geographic space, and by extension architectural space, a connection Ricoeur himself has outlined.16 They become spatial instances of what Ricoeur, drawing on François Dagognet, termed iconic augmentation: poetry’s capacity to actually add to reality, to carry an ontological weight comparable to that of being.17

The opacities from which these fictions are drawn are evidence of the failure of the promise, dating at least since the Enlightenment, of a complete and seamless mapping of the world. The imaging infrastructures of GIS seem to have built into them their own shadow, their own failure. I have already suggested that rifts in the system can be provoked by political circumstances. Perhaps other provocations of this failure are economic. The pressures of capitalism – commerce’s never-ending attempt to expand into new territories, displaced from real into virtual space – tend to push new technological products toward the edge of current capacities of processing power. As until-recently-new capacities are repeatedly exhausted by even-newer needs (or perceived needs), the rifts in these images emerge at an ever-displaced breaking point between means and desire. This phenomenon might in itself be related to the condition of inherent human lack asserted by Stiegler. It shares a space with his instrumental maieutic: between our anticipation of need, the creation of tools to fulfill that need, and the formation of our understanding. As that maieutic is the territory within which our being is drawn forth, it is no wonder the images that emerge from this space compel us so: their own rifts speak of analogous wounds within us.

Agencies

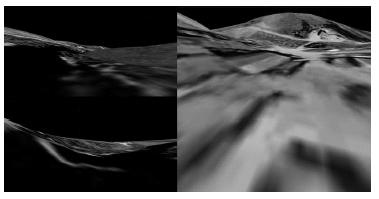

But if our compulsion by such images is a result of gaps within us, injuries we have sustained, we are not mere victims here. Beholding images like these, we continually push the limits of what they might convey precisely because we are not their passive consumers. Our imaginations act upon them – and they in turn push back. We can see further evidence of this in the sequence of images in Figure 8.4. These images were recorded after a jump into Ground Level View, that is, when Google Earth starts to react as though we were a body moving over the land. These three images present to us an aerial image mapped over the topography of the earth: that is, the superimposition of one piece of data (the image, captured by a satellite) with another (elevation variations, in all likelihood collected by LIDAR mapping).18 But rather than representing this piece of geography accurately, we find that as we move over it, both the image and the land it represents break up beneath us. Curlicues whip over aching voids. Structures collapse and melt into smears of barely recognizable photographic fragments. That condition is provoked by the motion of our technologized body (a cyborg) through space; one source of the image’s anamorphic distortion is our movement relative to it. This distortion occurs when we begin to act in that space, even if we are ambiguously, and simultaneously, embodied and disembodied there. These are perhaps the most architectural of the images I have shown here, for the same reason: they engage our bodies.

Our agency is implicated in this transformation of the image from a pure sign to a thing, as it begins to exercise its capacity to become something different. The art theorist Georges Didi-Huberman was preoccupied by works which move back and forth between being signs of something else and being compelling phenomena in their own right, raw flashes or splashes of color and texture.19 This distinction between signs and signification, I would propose, is exactly what is implied in the aerial images in Figure 8.4. In each, the signification of meaning breaks down at the very moment in which we begin to engage with the image. Such images cease to be objective representations of the earth. Rather, they become worlds in their own right.

Figure 8.4 Ground-level views of prairie landscape: courtesy Google Earth, © 2012 GeoEye

And here lies another form of agency: of the image itself. This is the moment at which a picture becomes not merely something we look at, but rather, something that looks back at us, ce qui nous regarde, a thing which we confront rather than observe. W.J.T. Mitchell speaks of something similar, the desiring image, an image that wants.20 The image is not simply a passive object for our consumption, any more than the prairie is: rather, it lives. We will recall here Stiegler’s proposal of a third genre of being, both inorganic and alive. If architecture, similar to these imaging systems and their products, might form such a genre of being, we would hope to identify or instill in it a similar condition of agency: an architecture which regards and confronts us, does not simply contain and serve us.

The introduction of agency to the image overturns any notion of “representational domestication,” to return to Waldheim’s term. These images are not tamed in the sense of being reduced to instruments; instead, they become wild. Andreas Broeckmann has referred to a transgressive disruption of codes as the wild in media.21 For Broeckmann that disruption is about excess, and the simultaneous undermining and animation of our technological culture – as explored by artists like Jean Tinguely, Herwig Weiser and JODI. While underlining the irony that much media art depends on a “tamed” technological environment to function at all, even that predicated in discovering “glitches” in that environment, Broeckmann asserts the importance of art that “transgresses these technical functionalities and explores failure, dysfunctionality, misuse, or uncontrollability as categories of aesthetic experience.”22 We have seen that even within as ambitiously encompassing a technological environment as Google Earth, such failures and escapes from control can be everyday occurrences.

I began this chapter by referring to pixilation, reading into it the confluence of two modes of manipulation – of land and of image. One irony of the etymology of this term is that the homophonous term pixilation dates not to the invention of the pixel in the 1960s, but to the nineteenth century. It was at the time an American term describing a person crazed, bewildered or intoxicated: as though led astray by pixies. The term became popular in the 1930s and 1940s, appearing in numerous popular entertainments; it was later adopted to describe stop-motion animation, a process that makes use of film’s dissection of images in time rather than space. Today it is generally accepted as a variant of pixilation, a word that was not invented until the 1960s. Might one propose a fictional, perhaps premonitory, etymology for this term, emerging from both information technology and from folklore, that encompasses both the sense of a digital instrument and the presence of a wild, disruptive force? The images discussed here are native to both of these domains. Despite their emergence from a platform that ostensibly instrumentalizes and commodifies the earth and its image, we can see that these images encompass a space in which imagination, compulsion, enchantment and perhaps even dread can be discovered. We stalkers of technology can seek out these qualities in the rifts between and the artifacts within such images, and imagine into them the fictions that allow us to gather a world or worlds.

Perhaps we might hope to pry open a similar space between today’s commodified architecture and its image. How might we explore the reversibility of these two, analogous to the reversibility of landscape and image on displayed above? What anomalies might we provoke in industrial processes of construction based on their own inherent contradictions, the rifts within them? What interplay between optical and haptic experience might we explore? And what hybrid fictional spaces might be created out of this exploration: neither merely built nor merely virtual; never either inanimate or alive, but both? What might our buildings become?

Notes

1 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt (London: Fontana, 1968), 214–218.

2 Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology,” in The Question Concerning Technology, trans. William Lovitt (New York: Harper & Row Publishers and Garland Publishing, 1977), 28.

3 Charles Waldheim, “Aerial Representation and the Recovery of Landscape,” in Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture, ed. James Corner (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999), 121.

4 Doug Rickard’s and Jon Rafman’s works, gleaned from Google Earth Street View, offer a compelling social commentary on abandoned spaces and subjects. See Rickard’s series “A New American Picture,” accessed December 27, 2013, www.dougrickard.com/photographs/a-new-american-picture/; and Rafman’s “9eyes,” accessed December 27, 2013, http://9-eyes.com/. Edward Burtynsky’s and Mischka Henner’s images shot from airplanes, automated drones, and satellites document the damage industrialization has wrought on landscapes. See for example Burtynsky’s own website, accessed December 27, 2013, www.edwardburtynsky.com/; and Henner’s series “Feedlots,” accessed December 27, 2013, http://mishkahenner.com/filter/works/Feedlots.

5 The farm boy was Philo Farnsworth. In 1927 he completed his image dissector, which scanned two-dimensional images and converted them into electronic signals; in 1933 he applied for a patent for an analogous system which projected electrons in progressive rows back and forth on the inside of a vacuum tube. An electronic transmission of the image had been imagined by others but never successfully completed; Farnsworth’s innovation was to break down images electronically, through the use of electrons, rather than mechanically, with mirrors.

6 Bernard Stiegler, Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus, trans. Richard Beardsworth and George Collins (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998).

7 Specifically André Leroi-Gourhan, philosopher Gilbert Simondon, and historian of technology Bertrand Gille.

8 Stiegler, Technics and Time, 133.

9 “What counts for the orientation of the spectacle is not my body as in fact it is, as a thing in objective space, but as a system of possible actions, a virtual body with its phenomenal ‘place’ defined by its task and situation. My body is wherever there is something to be done.” Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London & New York: Routledge Classics, 2002), 321.

10 Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 165–166.

11 Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Claude Lefort, The Visible and the Invisible; Followed by Working Notes (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 200–201.

12 Merleau-Ponty and Lefort, The Visible and the Invisible, 154.

13 Such disparities can be intentional, the result of governments censoring certain aerial views. Henner has documented examples in his series “Dutch Landscapes,” accessed December 27, 2013, http://mishkahenner.com/filter/works/Dutch-Landscapes.

14 This was captured directly from Google Earth; none of the images in this chapter have been Photoshopped.

15 He makes this argument in Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984).

16 See Paul Ricoeur, “Architecture and Narrative,” in Identity and Difference, catalogue of the Triennale di Milano, XIX Esposizione Internazionale (Milan: Electa, 1996), 64–72.

17 Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, 81.

18 LIDAR is a portmanteau of “light” and “radar.” A laser is used to scan the ground; the reflected light is analyzed to measure its distance from the laser source; from this elevations can be calculated and contours determined.

19 Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005).

20 W.J.T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2004).

21 Andreas Broeckmann, “Playing Wild!” in Sarai Reader 06: Turbulence, ed. Monica Narula et al. (Delhi: Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, 2006).

22 “Intimate Politics: An Interview with Andreas Broeckmann,” Furtherfield, online interview by the author, last modified October 8, 2011, accessed December 26, 2013, www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/intimate-politics-interview-andreas-broeckmann.