Evolution of the Design Process ‘from the inside out’1

Early twentieth-century educational experiments, widely recognized as pioneering and popularly labelled as ‘progressive’ created a firm foundation for articulating a vision of post-war educational environments.2 But those who actively promoted a vision of post-war schooling were more concerned to identify existing and emergent ‘good practice’ than to argue from precepts of progressive theory. ‘Progressive’ was a term that by the 1960s had become loosely associated with child-centred education and a form of primary school that resulted directly from the efforts of this group. However accurate or not the term ‘child-centred’, Mary Crowley would not have used it herself and neither would the Medds as a partnership. Rather, she would have identified with others pursuing and furthering excellence in practice which was already found to be flourishing in certain war-time elementary schools across the country.

Designing ‘from the inside out’ was common parlance in architecture influenced by Modernism. In school design it meant that architects had to become as familiar as teachers with the everyday practices of schooling. From this deep and extensive knowledge they would recognize the potential within the built environment for enhancing a new approach to curriculum and pedagogy. This approach emphasized learning through first hand experience, engagement with the creative arts, decision-making, observation, discovery and free expression. The key to communicating with teachers and encouraging them along these lines was to persuade them that their practice naturally led towards an innovative environment even though they might not themselves have envisaged this. But to achieve that end, certain procedures were seen as essential in the design process. These included close observation, planning through drawing, and planning through measurement, together with good organization and a commitment to challenge the hegemony of the conventional classroom. Their approach took considerable time and reflected the fact that the Development Group was operating within the public sphere and certainly could take more time and deeper measures than any contemporary architect in private practice could then or since afford.

EDUCATION OF THE EYE

Tackle the subject through educators and not through architects …just sit in the back, watch, and listen.3

Establishing a rhythm of visiting schools and observing and recording practice, the Medds relied on key HMI to direct them to meet teachers identified as nurturing what were then described as ‘growth points’ in practice. This would indicate that something unusual was occurring at a school as a result of experimentation led by the head teacher or an innovative class teacher, and that something was more often than not concerned with altering arrangements of space, furniture and time.

However, getting out of the office and going around schools to observe practice was not considered unusual at that time. Alec Clegg later recalled the excitement of this period and throughout his career often referred to certain schools where one could observe, in spite of the surroundings and environment, a transformation in educational practice taking place. He had in turn been inspired in this way of promoting educational progress by Christian Schiller whom he described as ‘the most inspired man I have known’.4 Schiller would, ‘go into a school – a drab and dull school perhaps – and he would nose around in it until he found a vestige of work with a spark in it – work that was doing a fire-kindling rather than pot-filling job.’5 He would draw the teacher’s attention to that spark and would encourage both the teacher and others in the school to appreciate the significant conditions that had produced that result. In turn the teacher would be encouraged to engage with their peers to help consolidate and spread good practice. Both Schiller and Clegg were keenly interested in the creative arts and the built environment of schools and so it was no surprise that they connected strongly and effectively with the Medds.

At the same time, local education officers took advice and inspiration from specialist teachers and advisers and the arts were pivotal in this respect. Clegg recalled the excitement of the work and the conversations with advisory staff.6 Education through various art forms was regarded as a key to the curriculum for younger children, laying a foundation for future possibilities in the child’s development. ‘The real discovery we made was that the Art, Music and Movement Advisers were all doing the same thing – inspiring teachers and children, building up confidence and conviction.’7

It cannot be over-estimated how much the arts were considered to be of primary importance during these years. Many educationalists in the UK and abroad were influenced by the publications of Herbert Read, particularly his book Education Through Art, first published in 1943.8 There Read brought a legitimacy to the arts at the centre of the curriculum, through a framework of psychologically based arguments. Significantly, he included as a final chapter an homage to the architects who had collaborated with Henry Morris at Impington in Cambridge where Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry were responsible for the design of a village college.

The first HMI attached to the Development Group was Leonard Gibbon, an educationalist greatly respected by the Medds.9 Gibbon directed them to schools in different parts of the country which they visited and while David made measured plans, Mary would talk with teachers about their intentions, sketch classroom arrangements and observe the activities happening through the day.

Typically, they and other architects from the Development Group and LEAs observed classrooms spilling over with activities where lack of practical space was compensated for by means of improvised use of corridors and cloakrooms. Edith Moorhouse, education adviser in Oxfordshire and a great ally and friend of the Medds, was an important influence in facilitating close observation of schools at this time. In a general survey of Oxfordshire schools, as early as 1947, she wrote,

On visiting a school one usually crosses an inadequately small and rough playground and passes through a small and dismal cloakroom before entering the classroom; one’s first impression on entering the door of the classroom depends a great deal on the teacher and the children within. One can sometimes forget the high windows and dingy classrooms in an atmosphere of pleasantness and lively activity.10

This ultimate faith in good teaching and the freedom of teachers to improvise with the spaces and equipment at their disposal is typical of the approach taken. Lack of space, pressure on resources and a new generation of imaginative teachers – many of whom were relatively new to the profession after having had former careers in commerce or business – combined to make for a vibrant situation in many schools. This generation of teachers inherited a spirited defence of the arts that had implications for the design of space and time in schools where ‘drawing, modeling, craftsmanship of all kinds, writing, singing, playing instruments, composing, rhythmic movement, dancing, drama, cooking, sewing, gardening – provide ways in which men’s (sic) instincts and ideals take shape and inform his delight in colour, sound, pattern movement, shape, texture’.11

Schiller was a mathematician yet saw the arts as the key to achieve deep and lasting learning experiences across the curriculum for children. He was also deeply interested in architecture and followed the work of the Medds over decades, often revisiting the schools they had designed to observe how they were working. As early as May 1946, Schiller set out his ideas on what should be the criteria of a good junior school including ‘that the children are expressing their powers in language, in movement, in music, in painting, in making things – that is to say, as artists’.12 Children making their own worlds and, in so doing understanding it, was a quality that chimed with the notion of designing school ‘from the inside out’. Self-sufficiency, practical engagement and appreciation of beauty were essential characteristics of an education and educational environment.

Some teachers began to follow this advice and school interiors became in many instances more challenging to navigate than had been the case in the past. Architects or inspectors visiting schools to observe practice,

found that they could not use the usual method of analyzing curricula, timetables and circulation. Instead they spent much of their time simply watching teachers and children … Although activities in the schools might at first sight appear unplanned, the team found that they generally proceeded within a carefully conceived framework evolved by the teachers through their own observation of the children.13

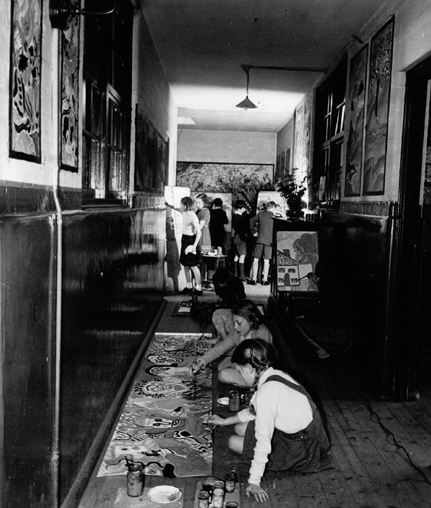

6.1 Children painting in a school corridor from ‘Story of a School’, a pamphlet published in 1949 by the Ministry of Education, telling the story of Steward St School, Birmingham. IOE Archives, J/1/1/16

By watching, sketching, analyzing and discussing it was possible gradually to build a foundation of first hand knowledge on which to base new and different school design. In its turn the new design could be used and tested by teachers who would recognize its successes and its failures and be stimulated by those to try out further new ideas, further improvisations. Back again to the architect; to watch, discuss, criticise – and again to try and interpret the requirements of education.14

Such principles were in keeping with attention to particular ways of seeing pupils and teachers and a commitment to recognizing the potential of both as creative beings. This viewpoint was at the time disseminated through a programme of training and professional development courses first at Dartington Hall in Devon and later at Woolley Hall in Yorkshire, organized by HMIs Schiller and Tanner and by Alec Clegg.15

But the new approaches to educating primary school pupils involved changes to time as well as space and use of materials. Key to the transformation beginning to occur was a variety of activities going on at the same time in the same space. As the Medds explained,

Of special interest to the architects … was the great variety of activity – painting on a scale ranging from an exercise book sheet of paper to a large mural; modeling and constructing with a wide variety of tools and materials; carrying out experiments; making music; impromptu acting; quiet reading and writing; listening to stories; arranging collections of interesting objects; looking after plants and pets – all probably going on at the same time and often in a room of little more than 500 sq ft with no sink and hardly any storage space.16

Material things, objects, and curiosities, it was believed, were essential elements to support discovery learning and child-centered teaching. School interiors should therefore be designed to accommodate careful display of materials and objects easily accessible to children. These features would endorse and promote teachers’ awareness that children of all ages were essentially active individuals, able to make choices and decisions as independent, resourceful learners.

There was a strong belief that even the smallest experiments by teachers within schools should be nurtured to influence both their own school and the wider community of schools. Robin Tanner’s intervention in this respect was pervasive. This he achieved by devoting all his time to teachers or schools on whom he knew he would have some effect, while practically ignoring the others.

Leonard Marsh was a student of Schiller, in turn succeeding to Schiller’s role as one of the most progressive teacher trainers, in Marsh’s case at Goldsmiths College in London. Marsh, like Schiller recognized the significance of the built environment and the importance of training the teacher’s eye towards a keener awareness of the visual. He exhorted teachers to ensure that the school building provided countless examples of everyday objects of good design, well-arranged books and other materials, and colours to support a range of work within the building and outside. In one of his books, Marsh adopted the concept of ‘growth points’ in the primary school for a discussion about school furniture. He suggested that ‘teachers will need to be on the look out for examples of craftsman-made furniture such as rocking-chairs and upholstered chairs for a reading corner, or for other special needs within the school. This will do much to preserve the growth points in our schools’.17

This practitioner-led approach to design has sometimes been criticized as being exclusive: the Medds followed the lead of HMI who spotlighted only certain head teachers and particular schools that seemed to be making the kinds of pedagogical changes they admired. It has been contended that as a result the Medd schools were too prescriptive and over-designed, the attention to detail suggesting an over-determined environment for teachers. David acknowledged this point of view but argued that it was not the case. He and Mary and others in the Development Group expected buildings to change through practice and buildings needed to be flexible enough to allow this to happen. Addressing the Architectural Association about the work of the DES Development Group in February 1965, he explained,

It is only by talking to and building for those on the frontier of experience, so to speak, that we can design buildings that challenge our best teachers with opportunities rather than limitations. In the passage of time, these opportunities may became limitations, and the stage is then set for further development…thus the shape of the building changes, and such changes are more important than those brought about by design opinion because they are based on changes in the life and activities for which the buildings provide.18

PLANNING THROUGH DRAWING AND SKETCHING

Mary Crowley’s love of drawing and compulsive application of it when viewing schools was at the heart of the design process she developed within A&BB. The creative spirit that inspired her to capture the world visually was a faculty that certain HMI also encouraged in teachers in order that they might overcome a common adult feeling of incapacity in art, and so that they might come to view human beings of all ages as capable artists. We have seen how on her many visits to schools and nurseries in Scandinavia and Europe, Mary kept a record of her travels in a sketch pad where she drew impressions but also made measured and detailed plans. This method was her architectural theory. She explained the process of design as evolving from sketches at the start of an observation to a building at the finish.

This evolutionary process began with sketches of ideas which emerged from the discussion and observation on the visits and which often formed the record of these visits. A sketch of the disposition of furniture and people at selected moments of the day vividly identifies the way teachers and children mould their surroundings to suit their work. The value of an architect’s first hand experience lies in his appreciation of detail as much as his understanding of trends. A drawing which records the plants growing on the window sills, the corrugated cardboard folded out to form a screen, the settee, rug, low tables and radio, the cooker and American cloth spread over the table, the ingenious display of children’s work, antiques and the original works of contemporary artists, do more to show how different is a classroom today from the classroom of even a few years ago, than do any number of deductions from meetings held around tables.19

Her sketches were then used in turn to stimulate discussion with teachers, cumulative in their effect of encouraging design to flow out of experience rather than be imposed from outside. Cost limits were temporarily put to one side while the various drawings were brought together towards assembling a whole, so as not to obscure the fundamental educational principles.

We have seen how, in her many travels and visits to school sites Mary took particular pains to sketch and so capture in drawing the natural environment of the school or kindergarten setting. These were for her not incidental aesthetic details in a landscape but rather an essential educational component. Thus already in Building Bulletin 1, ‘New Primary Schools’ published in 1949, we read of the importance of ‘planting and garden design’ not as an appendix but as a central aspect of the general space requirements. Mary was aware that such an emphasis on the educational benefits of landscaping would have been read with scepticism by those planning for restricted urban sites, but her purpose was to encourage more thought and persuade teachers and architects to act in collaboration on this advice.

It must be remembered how important the garden treatment of a school site is as an educational factor. The question has to be asked: ‘Is this a place in which children can enjoy themselves?’ Children should be surrounded by trees and plants, not by asphalt only; their interest will quickly be aroused if they are encouraged to learn about and care for the garden. A plan of the whole school and garden might be exhibited, with the names of the trees, shrubs and flowers to which the children could add their own records of planting.20

Mary, accompanied by David, attended many of the in-service training courses for primary school teachers organized by the Ministry of Education during the 1960s at Dartington Hall in Devon. The inspiration for these courses came from the educator and artist Robin Tanner, supported by Christian Schiller. Tanner had first met the Medds in 1955 during the development of Woodside school at Amersham and Finmere school in Oxfordshire. Tanner recognized, at Amersham, the potential of a fundamental change with respect to how teachers might view their work.

At the Dartington Hall courses, which the Medds attended regularly from 1961 for the rest of the decade, Mary and David would typically give an illustrated lecture about new developments in primary school design. Tanner recalled ‘David Medd spoke about the design of school buildings with a knowledge that was deep and sensitive.’21 Much of the course programme was devoted to encouraging participants to practice a wide range of creative arts that they might then take back more confidently to initiate in their schools.22 It was customary to have a poet, musical recital or writer as part of the weekend programme.

At the course held between 4 and 13 April 1961 on the theme, ‘Art and Craft. Their Place in Primary Education’, participants were encouraged to ‘take a walk through the gardens where you will meet three pieces of sculpture one of which is a much more considerable work than the others … sketch a piece in its setting … make drawings of details or of the whole from various positions.’23 Another set task to find and draw some of the rarer shrubs and trees illustrates how the artistic viewpoint of Tanner combined with Mary’s encyclopaedic knowledge of botany, with the object of teachers and children coming to know the value of plants and flowers in their school environments. In this setting, and with such encouragement, Mary would have felt valued and among friends.

The aim of involving the Medds in Dartington programmes was that teachers should become spacious in their thinking and practice, and through this gain appreciation of the significance of the built environment for their work. That in turn would underpin the hoped for exchange and understanding of how architects might collaborate with teachers in the design of schools for the future. Participants were encouraged to appreciate the architecture around the site, ‘delve into it and discover at first hand what are the motives and the guiding principles’.24 There were talks and discussions with teachers on the arrangement of furniture and fittings in teaching rooms and areas. A range of school furniture had been produced as part of the Development Group work and small scale models were made and brought to courses where teachers could discuss the effects of their different arrangements on a floor plan to the same scale.25

6.2 Edith Moorhouse, 1960, standing alongside a colleague, drawing, at a Dartington Hall summer school. DLM personal collection

Tanner considered the Medds to have had enormous influence in the development of primary education in these years. Having had the opportunity to visit Woodside school at Amersham, Tanner enthused ‘I never have enjoyed a schools as much; the sheer rightness and beauty of everything (and the refreshing absence of contemporary cliches) made it memorable … the ideal that ought to be put before Authorities and teachers everywhere.’26 And after the opening of Finmere School, Tanner wrote to Mary, ‘You can have no idea, I think, how considerable is your contribution to primary education. Finmere, for me, is the start of a new era, a realization of a dream.’27

PLANNING THROUGH POLICY

The war had provided not only the serious demand for reconstruction but also a heightened level of organization. As David Medd put it,

We had the organization in place. We had the HMIs in place. We had the educational Local Authorities in place … the Ministry [Ministry of Education] was giving the lead in terms of the money we had and the regulations and we kept on changing the regulations, every few years we’d change the regulations to make it more suitable. Architects had far more power then, much more power.28

A key factor in the development of schools ‘from the inside out’ was a particular style of administration established by leaders within pioneering LEAs among which Hertfordshire, Oxfordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire were noted examples.29

In Hertfordshire, as we have seen, John Newsom as Director of Education was convinced of the potential significance of the built environment in enhancing an approach to teaching and learning with the creative arts at the core. In Oxfordshire, another Hertfordshire man, Alan Chorlton, became director of the LEA in 1945. Chorlton inherited an Authority with many small and isolated village schools, which in his view had led to ’staff in-breeding and the absence of an outlet for new ideas from the outside’.30 His approach was in line with a strategy developed by progressive authorities during the post-war years which argued that the best way to bring about change was not to impose it from the outside but to encourage growth from within. He stated:

A Chief Education Officer in my view needed to try and disengage himself from desk work and get out and know at first hand the teachers, their working conditions, their problems, their quality as people and as professionals, and to be able to interpret these to his Committee, incorporating this first-hand knowledge in the framing of his advice on policy, priorities and requirements.31

A set of principles and common philosophy shared by this network of individual architects, teachers and policy-makers revolved around agreement that the educational setting should reflect the essential humanity of children and their teachers and nurture the development of each child in a warm, comfortable and enriching environment. Through practice, it was realized that teachers could, if supported, prescribe the environment of the school, release the children permissively into it, observe their activities to diagnose their needs, and draw upon their professional resources to meet those needs. And there was optimism that the new educational arrangements, including education for the very young child, would help to create social justice and prevent world conflict, ensuring peace and reconciliation in an era that still bore the scars of war.32

The discourse of the time, for schooling at all levels, emphasized a break with the past and projected the vision of a new dynamic relationship between school, community and wider society. School buildings that ‘fused’ with or ‘exploded into the community’ were imagined for older children, while ‘the expanding classroom’ was a motif for the primary school.33 Boundaries would disappear in the anticipation of school as community, while the local community would become part of school.34 Children’s decision-making and opportunity for exercising choice regarding their learning pathways would be a signifier of a modern education.

Mary Crowley anticipated this change in Building Bulletin 1, published in 1949. Here she envisaged primary schools where:

the older children will begin to investigate not only their immediate surroundings but the neighbourhood in which they live, gradually extending their interests to wider spheres. They will be taken out into the community (into the factories, farms, workshops) and the community will be brought into the school … school projects will lead to analogous activities outside the school, showing the interdependence between the two environments.35

Teachers, especially in primary schools, were exploring new approaches to teach a curriculum in line with a view of the child set out in the Hadow Reports on the primary school (1931) and on infant and nursery schools (1933). The 1931 document recommended that full use be made of the environment arguing that ‘the more closely the design of the primary school approaches that of the open air school the better’.36 Both reports had certainly been influenced by the convictions of Christian Schiller in his early years as HMI, and their influence increased in the post-war years when primary teachers were beginning to experiment with new ways of linking subject learning through themed work.

PLANNING THROUGH COMMUNICATION

When you ask teachers what they want, you are asking an unfair question because they have not been trained to answer it. The answer usually is cast in terms of wanting to do more conveniently what they are now doing. This is the fallacy of those who think they are virtuous when they ask the user what they want. It is more subtle than that.37

Significantly as it turned out, the first job for the Development Group was to migrate what had been learned from the Hertfordshire experience to the Ministry of Education; from the local to the national, recorded in Building Bulletin 1, ‘New Primary Schools’. ‘The Herts schools were an expression of local freedom which now had to be fitted into a national system which took cost, technique and education in an administrative, architecture and educational tripod.’38

The key to this successful migration was, as has been suggested, Mary Crowley’s ability to form strong friendships with some of the most influential and progressive HMI throughout the country. As David Medd put it, it was ‘a question of designers catching up with educators or working sufficiently closely with them, to see the design implications.’ Educators, in this sense, meant a select group of inspectors and teachers with whom the Medds had understanding and sympathy. In effect, the whole concept of the Building Bulletin was educational. As Andrew Saint points out, most LEAs were under pressure design schools for a new era but had very little expertise available to do so. Private architects often undertook school projects alongside other building types and did not have the time to research or become expert in this field.39 The Development Group’s function was therefore to provide an evidence base for school building in the localities.

The informal tone struck in the first Building Bulletin was sustained in subsequent publications and in this, as in many subsequent Bulletins, we hear Mary’s reassuring voice with vivid imagery drawn from school life, presented to encourage close critical observation and to entice teachers, architects and others towards new possibilities for education.40 The Building Bulletins recording developments in primary school architecture recognized and valued the skilled work of teachers. In the Bulletins primarily written by Mary, a tone of respect emanates from a deep knowledge of the subject and deep regard for what teachers were achieving against the odds. The consensus arrived at and promoted by means of these Bulletins was intended to ensure that teams of architects throughout the country would also learn much by watching the fluent improvisation of skilled teachers in an old building and come to understand that a key to successful school design was in ‘grasping the purposefulness that lies behind what may appear rather a mess’.41 The Bulletins were sold nationally and internationally. On a visit to Berlin in 1969, the Medds were delighted to discover torn out pages of Building Bulletin 1, ‘New Primary Schools’ pinned to the walls of the Education Offices.

During the 1950s, urgency of demand meant that the Development Group were concerned in the main with the design and building of new schools and as such the teaching staff were yet to be appointed. Schools were designed with plenty of time for discussion about the match between educational intention and environment but such discussions took place largely between the Medds and their colleagues and Chief Education Officers and members of the Inspectorate. Occasionally, as was the case with Eveline Lowe Primary School (1966), the future head teacher was appointed one year prior to the opening of the school thereby allowing for plenty of involvement but this was unusual. Once opened and functioning, the building was revisited in operation and the usual practice was that a Bulletin was written and published shortly after the school’s opening. The Bulletin generally described the process of design and detailed points that had developed knowledge more generally, an entirely new approach. ‘New Primary Schools’ established the template for future publications ensuring that children, not architecture, were the basis of the work and this early publication already included some of the first measurements of the bodies of school children.

In ‘New Primary Schools’ Mary Crowley’s experience and knowledge of educational factors is clearly evident. The statement ‘children are the basis of school design’ was entirely in keeping with her father’s philosophy and practice as well as contemporaries such as Carlton Washburne from the USA who by that time was advising the post-war Italian government on their educational policies. But such views were revolutionary in terms of prevailing attitudes in England that saw the school as primarily designed around the needs of adults, principally the teacher. However, key educationalists at the Ministry of Education and in local authorities envisaged that primary education would need schools designed to fit the child, so the prevailing climate encouraged such an emphasis.

It wasn’t enough that architects should get to know schools and how they operate, learning to observe and understand their rhythms and requirements. They should go further, they had to understand and like children. Mary communicated this ideal in her many public lectures where she argued the interdependency of the two professions should revolve around a radical transformation in the view of the child.

The architect can no longer work in the isolation of the drawing board and a schedule of regulation room sizes. He (sic) has to begin by liking and understanding children. He has to build up a knowledge of teaching in action. He has to exchange ideas with teachers and educators …We are obviously at the beginning of this kind of collaboration but one thing is certain that architects and educators are interdependent and must have a continuing almost day-to-day contact so that the cycle of design – experience – re-design can keep up with new educational ideas which will continuously be emerging.42

She reminded listeners that the best practice might be found in some of the less remarkable environments where teachers were succeeding while ‘not necessarily (having) good buildings. Indeed some had old and inconvenient ones; and the improvisations of resourceful and imaginative teachers, and their achievements despite their premises, were of particular interest.’43

Occasionally, a direct suggestion might be made whereby the internal design could be altered to enhance a particular view of the child. Thus, Christian Schiller is noted to have remarked to the Medds that the basic structural elements of a school hall – the columns – might be turned over to use as a climbing frame. An adaptation of this idea was made at Finmere School, in Oxfordshire, where climbing ladders were installed as part of the framework in the central space.

Progressive educationists such as Marsh thought that architects should be designing for an ever increasing variety of interconnected activities, readily available to groups of children and their teachers for exploration of problems they set themselves. The removal of familiar barriers and boundaries that had traditionally separated children from other children according to age, and the child from its teacher, was a sign that this was achievable, at least in infant and primary settings. This included abolition of the division between infants and juniors in all-through primary schools, and the design of schools without doors, as, it was argued, these hinder the flow of ideas from imaginative people who initiate them or from gifted children who develop and extend them.

PLANNING THROUGH SCALE

The Medds believed that design of the school building should take people and education as the starting point. Hence their concern with scale, with sight-lines and with accurately measuring children’s bodies at various ages. Being able to see out of the classroom towards the skyline and to view trees and landscape at various stages of the year was an educational ideal and the architect must respect this as an essential part of the child’s experience. Measuring children, noting their height at various ages, their reach, their sight-lines while standing or sitting, began in earnest during the early 1950s at the Ministry of Education where the Medds took advice from the anatomist and zoologist Solly Zuckerman with whom they worked on children’s anthropometric studies at Birmingham University.44

Encouraging this interest was John Newsom who believed, along with his friends Henry Morris and Mary’s father Ralph, that the child was educated by the whole environment in which he or she was schooled, as well as by instruction. Schools were to become environments where children could not only feel they belonged but could also easily participate in rearranging and caring for on a daily basis. Hertfordshire’s Chief Architect, C. H. Aslin, agreed with this view that aligned with Mary’s instincts. ‘The classroom was to be the child’s familiar place, not only where he would have to work and play, but where he could keep his belongings and pin up his own drawings and contribute to the creation of his own surroundings.’45

The Medds were meticulous in acknowledging the way that children at different stages of development might be accommodated and supported physically in the school environment. Their carefully considered appreciation of furniture, fittings and spaces scaled to the child’s body is a striking feature of their work. Designing ‘from the inside out’ meant for the Medds starting with the educational process – the relationship between the teacher, the pupil and the immediate environment and designing this in detail with the relationship of the whole and the parts held always in play. Detail was of utmost importance, hence Mary’s concern with pin-boards and David’s that the height of coat pegs should enable young children to use them freely.

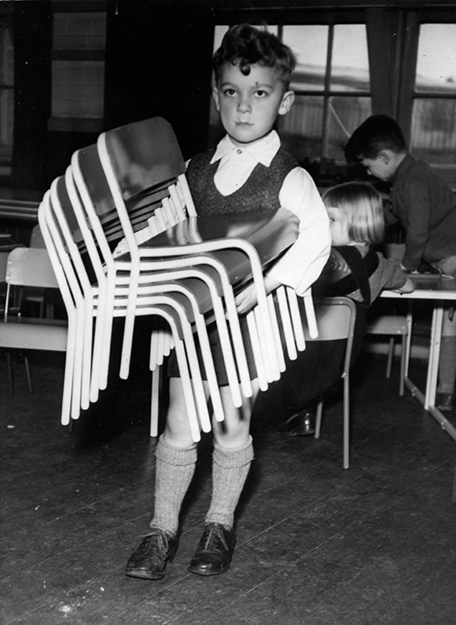

The body of the child, at different ages and stages of development, was rigorously studied and measured to ensure that furniture designed for the pioneering primary schools opened during the 1950s and 1960s would fit exactly, ensuring comfort, appropriate scale and thus a sense of belonging. The work on furniture had begun during the Hertfordshire years. In the spring of 1946, an ‘exhibition of infant’s work in materials and furniture’ was held at Corner Hall School, Hemel Hempstead where many suggested designs by Hertfordshire firms were on view, ‘light enough for the small children to carry about themselves’.46 Significantly, there were also displayed small tables that could be used ‘for building purposes’ as the school furniture needed to support the constructionist pedagogy envisaged.

The child whose legs were hugged by a window bench when seated would feel that the school had been made for them. Designing all of the furniture for Woodside School at Amersham with regard to anthropometric data set the basis of British Standards for School Furniture for a generation.47

The influence of Mary’s father and his life’s work is clearly recognizable in this concern with what Ralph Crowley had termed ‘the whole child’. Mary’s lecture notes reveal the distinctive qualities that she felt to be so important for an environment scaled to the child.

Scale … has its influence on character. Most adults see with eyes that are about 5ft 6inches above the floor, but everything in the primary school is seen and used by people whose eyes are about 3 ft 6 inches above the floor (and who don’t get much chance of looking down on things). It is unpleasant not to be able to see out of a window, not to be able to reach a book on a shelf, to have to work at too high a table. Only if dimensions derived from body measurements and posture studies are constantly applied to every fixture and item of equipment can an influence be brought to bear on an interior of the building as a whole.48

For the architect designing schools, the starting point was always to be children, their views, their needs, their aspirations and their physical capacities.

Their elbow heights will determine the height of working surfaces, sinks, door handles. Their eye levels will be a guide to the height of window transoms, mirrors etc. Study of their posture will determine the design of tables or chairs … it means that the scale and proportion of the building itself grows out of the life of the people inside it rather than it being an expression of an abstract, geometrical idea.49

One primary school teacher who at one time taught in a school influenced by the Medds recalled regularly going down on his knees to his wall displays of children’s work.50

CHALLENGING THE HEGEMONY OF THE CONVENTIONAL CLASSROOM

Education is opening the classroom doors and is penetrating into every part of the school. What some architects and teachers still perhaps do not appreciate is that you cannot divide the school into teaching and non-teaching areas. The whole building and garden is becoming the ‘teaching area’.51

Reflecting on the approach taken at this time to planning the design of new schools, David Medd remarked, shortly before his death in 2009,

When starting to plan these schools, we were faced with the dominance of the classroom without which a school is unimaginable. It was designed for people to pay attention, write and read, above all, to keep still, and furnished with table and desks and very little else.52

The school of the future, as he and Mary saw it, would be an environment that permitted learning through doing, making, creating and reflecting, filled with spaces quite unlike the classrooms of old, now stocked with lightweight moveable furniture that could be managed by the smallest children.

Challenging the hegemony of the classroom was a driving principle of educational design that Mary and David shared in equal measure. In their youth they had both experienced a progressive education in schools where traditional classroom arrangements were already considered to be a thing of the past and where learning through projects by means of research and a wide variety of methods at a pace and in a space of one’s own choosing was the accepted norm. They believed it was only a matter of time and the degree of energy exerted by such as they in positions of power and influence, before teachers, guided by enlightened educationalists, would see the positive benefits for children and teachers alike, of classroom-less schools. This would happen first in schools for the youngest but the benefits would spread further up the age range eventually affecting schools for older children and adolescents. This is evident in the principles guiding their work at the Ministry of Education as well as in their comments on schools visited abroad. In Sweden in 1967, David described what they understood as ‘modern educational ideas’ with a radical democratic quality emphasizing, at least, elements of individual choice.

Modern educational ideas surely demand that there should be some reconciliation between the formality of design serving a centrally administered curriculum, and the variety and vitality in design that stems from providing for what people want to do. As modern educational ideas percolate up, the Grundskola (Comprehensive school) it seems that variety of teaching methods, more initiative from the teachers and the closer link between education and individual needs will banish the standard room and a standard corridor basis of school design that has lasted for so many centuries.53

6.3 Pupil carrying chairs, Hertfordshire school, October 1948. Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images

Addressing teachers attending conferences at Dartington Hall, the Medds had the time and opportunity to critically consider how schools were currently imagined. They described these as characterized by, ‘certain traditions in educational provision that blind most of us from either asking for schools or designing schools uncontaminated by what has gone before’.

By this they meant that one of the most difficult tasks in designing new schools was removing the image of the classroom from teachers’ imaginations and from architects’ drawing boards. In 1971, reflecting on a decade of ever more courageous movement from the traditional model of school towards a series of spaces designed to support a never ending variety of learning dispositions and activities, they argued,

If children were learning at different rates and in different ways, it was little wonder that the homogenous character of the conventional classroom had to be destroyed, that the rigid structure of the old classroom-corridor school had to be changed. It could not respond.54

The Medds, and the schools they were best known for, have often been confused with the concept of ‘open plan’, which from the 1970s began to be associated with difficult teaching and learning conditions and an over extension of progressive methods. The term ‘open plan’ was often used interchangeably with terms such as ‘progressive’, ‘informal’, and ‘child-centered’.55 David often remarked that the planning of their schools was the opposite of open plan and Mary and he would never have used the term to apply to their designs. Mary talked about the task of creating ‘visual order’ out of a true appreciation of the ‘richness, vitality and variety of children of primary school age’.56 In other words, in the past, architects had designed according to one notion of the pupil arranged in rows within box-like classrooms lined up along lengthy corridors useful only for circulation. From a fresh approach to thinking about the varieties of ways of being a child within a school, the impact on the environment would be profound.

The design solution was complex and consisted of a range of subtle, modulated spaces, neither completely open nor closed, where groups of children might simultaneously carry out different projects at different educational levels. For example, Finmere Primary School in Oxfordshire (Figs 5.15 and 5.16) was not simply a series of open spaces but a carefully designated set of differently conceived areas with specific intentions for use, affording the highest degree of flexibility. Key features included ‘home bays’ and spaces such as ‘sitting room’ and ‘kitchen’ reflecting a domestic realism in the educational environment. The whole space was divided by means of two folding partitions and a series of fixed wall partitions creating work bays, offering space for a variety of possible uses. Malcolm Seaborne noted in his study of primary school design, that the financial constraints placed by governments on the design of new schools during these years did not enable the full scale of the experiment started in schools such as Templewood in Hertfordshire (1950) and Finmere in Oxfordshire (1959) to be realized. This, together with a reluctance held by many teachers to let go of tried and tested approaches to teaching in the classroom made architecturally led reform difficult to sustain. By the mid-1970s, government and professional pressure was building against the freedom of experimentation and innovation which had been enjoyed by teachers, at least in primary schools, for over a decade.

Designing school ‘from the inside out’ was a scientific and artistic process that conjoined head and heart, educator and architect, teacher and child in new idealized relationships during these years. There was clear vision, sound research, evaluation and adaptation and a consciousness of working with and not against the grain of human nature. Emphasis was placed on the importance of sound research-based principles rather than the latest fashions or fads, and in that sense the efforts, aspirations and achievements of those who worked together for a new kind of school for young children were sometimes poorly understood by parents and politicians. Collaboration made sense not only politically and economically but also aesthetically in the way that demands of the immediate post-war era were met and results disseminated through collaborative efforts.

NOTES

1 C. Burke (2009), pp. 421–33.

2 For an examination of this period of experimentation in educational provision for the younger child, see R. J. W. Selleck (1972) English Primary Education and the Progressives, 1914–1939. London. Routledge and Keegan Paul.

3 DLM letter to author, 13 May 2008.

4 Alec Clegg cited in J. Stuart Maclure (1967) Curriculum Innovation in Practice. Report of the Third International Curriculum Conference. London. HMSO. p. 27.

5 Ibid.

6 Alec Clegg cited in Marsh (1987) p. 33.

7 Alec Clegg, cited in Marsh (1987) p. 27.

8 Herbert Read (1943) Education Through Art. London. Faber & Faber.

9 S. Maclure (2000) The Inspector Calls. London, Hodder & Stoughton p. 64.

10 Edith Moorhouse, Oxfordshire Education Committee. ‘A General Survey of Conditions Affecting the Life and Staffing of Rural Schools’. April 1947. p. 2.

11 Extract from lecture by Dorothy Hammond cited in Marsh (1987) p. 30. Hammond was an important influence on Schiller and others and was the last woman to hold the post of Chief Woman Inspector, retiring in 1947.

12 C. Griffin-Beale (ed.) (1979) Christian Schiller in His Own Words. London. A. & C. Black.

13 BB, 36, p. 5.

14 David and Mary Medd (1971) pp. 7–8.

15 For more on such courses, see Peter Cunningham (1988) Curriculum Change in the Primary School Since 1945. London: Routledge. Chapter 3.

16 BB, 36, p. 5.

17 Leonard Marsh (1987) ‘A Case-study of the Process of Change in Primary Education Within Oxfordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire from 1944–1972’, D. Phil unpublished Thesis, University of York. p. 110.

18 DLM address to AA, ‘The Work of the D.E.S Development Group. Gordon Wigglesworth, David Medd, John Kay and John Hitchin’, 18 February 1965.

19 BB, 36, p. 19.

20 BB, 1, p. 9.

21 R. Tanner (1987) p. 165.

22 Ministry of Education Course, no. 1. ‘Art and Craft. Their Place in Primary Education’, 4–13 April 1961. ME/M/5/4.

23 Ibid.

24 Notes for the Ministry of Education Course, April 1961.

25 DLM notes, p. 24.

26 RT to MBC and DLM, 1 April 1958.

27 Robin Tanner letter to MC, 3 April 1960. ME/Q/8/1.

28 DLM in conversation with George and Judith Baines on Arran, 4 July 2007.

29 L. G. Marsh (1987) ’A case-study in the process of change in primary education withinOxfordshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire from 1944 to 1972’,unpublished PhD Thesis, University of York.

30 Letter from Chorlton cited in Marsh (1987) p. 61.

31 Letter from Chorlton cited in Marsh (1987) p. 61.

32 Malcolm Seaborne (1971) Primary School Design. London. Routledge and Keegan Paul.

33 Eileen Molony (1914–1982), ‘The Expanding Classroom’ (1969). The objective of this BBC television series was to provide an explanation or illustration of how ’Britain’sprogressive active classrooms’ work and to demonstrate some of the attempts to move over from subject-centred to child-centred education.

34 Philip Toogood (1984) The Head’s Tale. Telford. Dialogue; A. H. Halsey (ed.) (1972) Educational Priority, Vol.1: EPA Problems and Policies. Report of a research project sponsored by the Department of Education and Science and the Social Science Research Council. London. HMSO. p. 79.

35 BB, 1. p. 25.

36 The Hadow Report (1931) The Primary School. p. xvii.

37 DLM notes for a talk to be given at Dartington Hall, January 1968.

38 DLM notes on MBC, 17 June 2005.

39 A. Saint (1987) p. 126.

40 Mary worked with David Medd and Michael Ventris on BB, 8, (1952), St Crispin’s School Wokingham and on BB, 16, Woodside at Amersham (1958).

41 BB, 36, p. 9.

42 MBC lecture notes. ME/M/5/4.

43 BB, 36, p. 5.

44 DLM (2009) p. 15. Baron Zuckerman, OM, KCB, FRS (1904–1993). Zuckerman was Sands Cox Professor of Anatomy, Birmingham University, 1943–68 (Emeritus).

45 C. H. Aslin, Education, 27 April 1951.

46 Note on back of image, Fig. 6.3.

47 See Building Bulletin, 16.

48 MBC lecture notes. ME/M/5/4.

49 Ibid.

50 Peter Cunningham taught for a time during the 1980s at Eynsham Primary School in Oxfordshire under the headship of George Baines.

51 MBC lecture notes, ibid.

52 DLM (2009) p. 13.

53 Notes from Swedish visit 1967. DLM typed notes, p. 3.

54 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 9.

55 Peter Cunningham (1988) p. 128.

56 MBC lecture notes, Sweden file. ME/G/26/2.