First Architectural Work: From Housing to Education

It was not thrilling but was quite enjoyable. I don’t think I did anything of real interest – it didn’t click.1

A generation of optimistic young people who had been raised and educated within middle class families with socialist or utopian leanings and who had been schooled at a variety of new progressive institutions came to maturity in the early 1930s. In Britain, the generation that established and inhabited the first Garden Cities produced sons and daughters some of whom grew to adulthood committed to the idea that design could meet the needs of society and create a better quality of life for all. Their upbringing emphasized unity of hand, heart and mind in the service of the public good and the central role of the arts in civic life. As we have seen, Mary had experienced such an education and flourished as a pupil at Bedales School. Other contemporaries with a bent towards making art had found their way to Oundle, an independent endowed school dating from 1556 that from 1893 until 1922 came under the leadership of F. W. Sanderson. Sanderson reconfigured the school to support a progressive ideology of ‘learning through doing’. Jack Pritchard, later a pivotal figure in the British Modernist movement, found solace at Oundle after first failing at more traditional schools.2 This was also the case with David Medd who found the arrangement of workshops and laboratories, in place of traditional classrooms, suited his passion for construction. This generation born close to the turn of the century had witnessed the impact of the Great War and the subsequent rise of socialist politics that ushered in a gradual greater acceptance of public provision of education, housing and health.

As well as the role of the state, the role of the arts in society came increasingly into question and a number of intellectuals of this generation and those slightly older were experimenting with theory and practice which addressed the question of the relationship between the arts and science in general, and the role of the artist and designer for the public good.3 While this was a question addressed in England, as we have seen, the impetus came both from Europe and the USA. In Finland, Alvar Aalto, who was greatly admired by Mary and her contemporaries, exemplified through his work the idea that everyday objects might become objects of beauty through a design attitude that fully appreciated their practical function as well as their aesthetic. The Bauhaus attempted to unite the arts, crafts and design into one educational project addressing the everyday functional and aesthetic needs of modern society, while in the USA the Cranbrook Academy for the Arts was beginning to emerge as a new form of arts school dedicated to the ideal of the integration of art in daily living and inspired by the American Academy at Rome. Within this climate of experimentation, political upheavals of the 1930s with the rise of Fascism had the effect of bringing many individuals together in their efforts to find opportunities to work – to make art and to build.

As the Medds later reflected,

In an age of new social priorities after the war, there were architects about who believed that the starting point of design – whether for education, for housing, for hospitals – was the needs of people, not a style or grammar of architecture, not a statement of pre-determined form … . they believed it to be possible, by starting with direct knowledge of what people wanted to be and to do in a new building, eventually to win through to design of architectural quality.4

For newly-qualified architects across Europe, housing was the major social issue of the day and many of Mary’s contemporaries, such as those who were members of the Modern Architectural Research or MARS group (1933–1957), were establishing their careers as architects in public housing.5 Mary was listed as a proposed participant in the MARS group as early as 1933 and was nominated by her friend Elizabeth Denby to be a member in 1937 but does not appear as a listed member until 1940.6 Mary’s travels with her family and with fellow students at the AA, already enabled her to see at close hand the establishment of a completely new form of social architecture and it was to housing that she looked for her first architectural commissions during these years. Housing might well have become the focus of her career, but her frequent return visits to Bedales, continuing friendship with Laurin Zilliacus and commitment to her father’s wide ranging interests all served to maintain the focus on education.

London was then the centre of a nexus of talent and opportunity. In his autobiography, Max Fry observed, ‘so little divided us then, the artists, the philosophers, the engineers, even the industrialists who were members of this society’.7 The travel of ideas and the exchange of knowledge across Europe had affected all countries involved in re-envisaging their urban landscapes following the First World War and in England a public commitment to deal with slum clearance through local government municipal action was one of the many forces that stimulated the modernist movement in architecture.

Some of the housing models emerging on the continent were particularly inspirational. Socialist housing schemes for families of skilled workers in Vienna (Heiligenstadt – Karl Marx Hof), Amsterdam and Rotterdam illustrated how a progressive politics might change the cityscape, promoting health, well-being and community. Utopian housing schemes with integrated childcare centres and kindergarten must have appeared to Mary as at least part fulfilment of the Garden City movement that her family had been so closely associated with on a grander scale.

3.1 Kensal House, Kensal Rise, London, 1937. Photograph by Edith Tudor Hart (1908–1973). RIBA Photographic Collection

Utopian experimentation in city planning required designers who could identify with the lives and experiences of ordinary families, especially with women and children. The 1930s was a pioneering age for nursery education so it is not surprising that one of Mary’s first jobs was advising the Kensal House experimental flats development in North Kensington. Mary’s special interest and knowledge of education was sought by her friend Elizabeth Denby as housing consultant for J. Maxwell Fry’s firm working on the innovative scheme.8 This significant modernist development, commissioned and financed by the Gas Light and Coke Company and intended for re-housed slum dwellers, was opened in 1937 and included an on-site nursery.

The nursery at Kensal House was set as an unusual curve following part of ‘a round shape of a former gas-holder on the site’ and contained certain elements that were to continue over the decades of Mary’s design of schools for younger children.9 The playrooms were light and airy and opened out easily to a terrace allowing for outdoor play. The buildings at the time were known as ‘the sunshine flats’.

Denby, who preferred to think of Kensal House as an ‘urban village’, was, like Mary, motivated by Scandinavian developments in social architecture. In particular she was inspired by a social climate in Stockholm that encouraged people to build their own houses out of wood and prefabricated materials. Mary later reflected that Denby’s enthusiasm for such projects encouraged her own interest in simple construction and prefabrication.10 They became firm friends and, as already noted, travelled together to Sweden in the 1930s.

Another important development in London during these early years in Mary’s career was the Peckham Health Centre, designed in 1935 by Owen Williams, which became known as ‘one of the great public-health experiments of the twentieth century in the UK’.11 The building was designed to have an impact on the activities within it. Freedom of movement and visibility in an open-plan structure were considered important in promoting social cohesion, spontaneity of behaviour, and awareness of opportunities for action. At the heart of this experiment established by a husband and wife team of scientists was a school.12 At the Peckham Health Centre, health was defined not as a state but as a process of interaction with the environment. In a similar sense, the education that Mary had experienced and would seek to advance was also best understood as a process of interaction with the environment. It seems that through these initiatives the traditional concept of school focussed exclusively on the young was expanding and that Mary’s project, explored in her final year thesis of ‘An Educational Centre for Arts and Sciences’ was becoming realized in different forms, not only by Henry Morris’s village colleges in rural Cambridgeshire but also in the inner cities as at Peckham. Mary must have delighted in a building that corresponded with Quaker principles and supported democratic management where at the heart of the building an Olympic-sized swimming pool reflected the sunlight from above. ‘Flanked on one side by the gymnasium and on the other by an assembly hall which could be used for meetings, dances, and plays, the pool had long glass panels on either side, providing a view into it from the lounge or “long room” and the cafeteria, and a view across it from one to the other.’13 Here mothers could meet while their children played and families could enjoy the social facilities. Mary recognized these efforts as ‘a great movement, one that should have gone on but was stopped by the war’.14 It was only after the war that the first Hertfordshire new school buildings could begin to reflect some of the lightness and optimism first laid down in the extraordinary building of light, water and sunshine at Peckham.

Around this time also, examples of Modernist housing were beginning to appear in England: we have noted Mary’s familiarity with High Cross at Dartington and she would have been aware of her fellow AA student Wells Coates’ celebrated first building, Lawn Road Flats, completed in 1934. The political climate in Europe was effecting a movement of ideas and practices across continents and London, the city Mary knew best, provided a stopping off point for many architects, designers and artists fleeing oppression. Lawn Road provided a base for many of them in exile.

Exhibitions provided an immediate vehicle for emigrés to become involved with the local artistic and architectural communities of the metropolis and also offered Mary interesting work at this time. One of her first tasks after returning from Germany in the autumn of 1933 was to work on models for the Building Trades Exhibition at Olympia. She was in stimulating company,

Elisabeth Scott, Chesterton and Shepherd were there a good deal. Scott had to spend most of the afternoon making a model of a really bad cinema – as bad as possible – too bad to make her, of all people, do that! 15

But the most important and lasting work that she completed during these years was a group of three houses at Tewin in Hertfordshire.16 This was Mary’s first commission as a qualified architect bringing her instant recognition, and has frequently been referenced and illustrated since.

When land known as ‘Sewell’s Orchard’ came up for sale, Mary’s mother wanted to acquire it as Sewell was a family name. Naturally, she turned to her newly qualified daughter to plan the scheme. Mary is credited as architect of these houses, although Mary’s brother-in-law Cyril Kemp did some drawings and Brandon-Jones offered some collaboration on the scheme, recognized as a particularly fine expression of modernist domestic architecture of the time.17 They were designed for her parents, sister and brother in law, Cecil Kemp, and a family friend, Rowland Miall and occupied in 1936.

One of the Miall children, William, recalls,

The home at Tewin was a delight. Three households in the Garden City, the Crowleys, the Kemps, and ourselves had decided to share a 1½ acre plot called Sewells Orchard in open country outside the village. We were all Friends (Quakers) Ralph and Muriel Crowley were to have the middle part of the plot, and would share it with their architect daughter, Mary. Elfrida, another daughter who was married to another architect, Cecil Kemp, would have the lower part of the plot and we would have the upper part. The two architects collaborated together to produce three rather similar and very modern houses which attracted a good deal of architectural attention and comment. Groups of architectural students would sometimes turn up on Sunday mornings and hope to be shown around.18

3.2 Sewell’s Orchard, Tewin. Completed 1936, listed 1981. IOE Archives, ME/A/7/3

3.3 1–3 Willow Road, Hampstead, London, by Ernő Goldfinger (1939). RIBA Photographic Collection

Ernő Goldfinger designed a similar group of three houses at 2 Willow Street, Hampsted in London, the middle of which he and his wife occupied until their respective deaths. These houses bare a strong similarity to the houses at Tewin and it is perhaps no coincidence that Mary Crowley and Ernő Goldfinger worked together on various projects during the years that saw the planning and design of both sets of family houses.

Mary described the design as rather Scandinavian, especially the mono pitched roof that she thought had been realized very well by a local builder from Welwyn Garden City, a friend of the family. The Scandinavian influence was clearly a result of her many visits to Sweden and Denmark over the previous decade. By this time, the mid 1930s, she was even beginning to describe herself as Scandinavian, ‘there’s a simplicity and a friendliness of Scandinavia that just becomes part of you’.19 However, she believed that the houses were recognized by the architectural community not especially for their appearance but because their completion coincided with an exhibition surveying modern development in European housing. The exhibition was hosted by the Building Centre in November 1936. An elevation of the house designed for the Crowleys became an installation in this important exhibition.20 While the exhibition was in preparation, Mary had worked with Justin Blanco-White,21 her closest professional friend, on a book, Housing: A European Survey for the Building Centre.

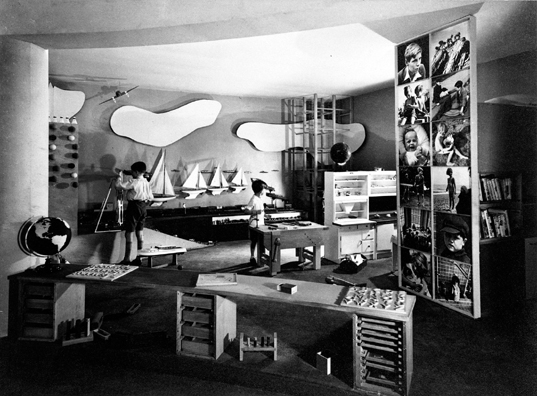

The houses at Tewin were recognized as significant statements on modern architecture and were also featured alongside other developments including Kensal House at the MARS group’s 1938 Exhibition of the Elements of Modern Architecture. The MARS group exhibition was a significant statement by a new generation of architects and it attracted an audience of seven thousand spectators including Le Corbusier.22 This exhibition was organized initially by the Hungarian-born Bauhaus emigré László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) before he left Britain for the USA, handing the responsibility over to Misha Black (1910–1977). Individual MARS Group members designed different sections of the exhibition. The introductory essay to the catalogue was written by George Bernard Shaw.23 Ernő Goldfinger was responsible for the mother and child section and his interest in children and education is evidenced in his design of the children’s section of the British Pavilion one year earlier as part of the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (Fig. 3.4).

In the final years of the decade, Mary began to work on the design of flexible spaces for family and nursery accommodation in various combinations with her friends from the AA at Goldfinger’s Offices in Bedford Square. This was interesting work that kept her tuned to the world of childhood and education however she had to contend with Goldfinger’s rather mercurial temperament. Like other architects she worked alongside during this period, Goldfinger was interested in a more permanent arrangement, which Mary resisted.

The schemes that they worked on together reflected the approach of the MARS group – to discover architectural solutions to social problems. The results included some of the earliest uses of prefabricated parts for school design including a flexible nursery school designed on a unit system, ‘a completely prefabricated building with each wall made of wooden wall units (6 ft. wide) bolted together, weather-boarded on the outside and fibre-board on the inside’.24

3.4 British Pavilion, Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris 1937: the children’s section with furniture and toys by Abbatts. RIBA Photographic Collection

In 1934 the Nursery School Association had commissioned Goldfinger to design a cheap standardized nursery classroom in timber – known as the expanding nursery – and he and Mary revised the design in 1937 so that the parts could be multiplied and used to extend to the desired number of units, an early form of prefabrication which was to become so significant in post-war school building design.25 It provided for flexibility through three alternative layouts to accommodate 40, 80 or 120 children and its 6 foot component modules were intended to be manufactured by the joinery company Boulton and Paul. A prototype was erected but its mass production was never realized.26

It was here, at Goldfinger’s offices in Bedford Square in 1938, that David Medd first came into contact with Mary Crowley. By his own account, she was working on Goldfinger’s adaptation of the heliograph, a machine that projected light drawings. David was making a delivery and noticed a striking image, ‘a vision’ that he retained in his memory until the end of his life.27

In the last year before the outbreak of war there was an expectation of considerable population disruption and the need to provide emergency accommodation for evacuated children. In response, The Building Centre proposed a competition for architects to design a camp for children that might be easily transformed into holiday accommodation in peace time. Ernő Goldfinger, Mary Crowley and her friend Justin Blanco-White submitted an imaginative and innovative proposal using prefabricated standardized units that drew a lot of interest.28 Mary’s influence on the scheme can be detected not so much in the advanced engineering but in the attention to atmosphere, well-being and opportunities for play. The units were grouped ‘to form semi-enclosed gardens, with flowers, pools and trees, where children could sit and read and rest’.29 The entry won second prize and acclaim in the architectural press. ‘They submitted a most competent set of drawings and models for two alternative schemes. Their analysis of the problem was thorough, their solutions exciting and imaginative.’30

After the war Goldfinger went on to design two more schools in London using his own prefabricated concrete techniques; Westville Road Primary School, Hammersmith (1950) and Brandlehow Nursery School, Putney. We might conjecture that Goldsmith had learned much of value from his young assistant before the war that was eventually realized in the planning of these schools.

Mary’s interest in education, therefore, was maintained at a time when she might have turned to housing. Her father’s continued professional involvement as well as his circle of friends sustained the association in Mary’s mind between Modernism and progressive education. Ralph Crowley was a close friend and admirer of educationalist and art patron Henry Morris who served as County Secretary for Education in Cambridgeshire between 1922 and 1954. The Cambridgeshire village colleges founded by Morris were pioneering in their educational aims and one at least, at Impington (1939), purposively combined modern education with modern architecture through the combined efforts of Morris, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry.31

Competitions were a standard means by which young architects could show their mettle. In 1937, The News Chronicle organized a competition for the design of a new secondary school. Whether Mary considered entering, we do not know but one of her ex-colleagues at the AA, Denis Clarke-Hall entered and won with his design for a new girls’ High School at Richmond in Yorkshire. Clarke-Hall suggested that the 1930s ferment of ideas and styles emanating from the AA coincided with the beginnings of an interest in schools. He admitted knowing ‘absolutely nothing about schools when drawing up the scheme’ for the competition.32 However Mary’s constant interest in education and school buildings was kept alive by interesting and far-reaching developments closer to home in the new Cambridgeshire village colleges which she visited with her father.

We’d go together and he was interested as much as I was in all the education that was going on there and education as part of the community and doing something interesting and rather different.

Many of Mary’s friends were also in their early 20s and were finding partners and marrying during these years but Mary resisted even though there were ample opportunities to follow suit. As an attractive and talented young woman she was courted by several admirers among whom were architects, educators and designers including Geoffrey Jellicoe, who proposed marriage in 1934, and fellow student at the AA John Brandon-Jones, with whom she did measured drawings of Wren’s Winslow Hall in Buckinghamshire for the Wren Society and at Hatfield Road33 (Fig. 3.5). It seems she needed to find some really engaging work before she could settle her personal life.

3.5 Mary Crowley and John Brandon-Jones measuring Hatfield Road. IOE Archives, ME/A/3/7

During the war years Mary eventually found planning work within schools, as will be discussed below, but was still unsure as to where her future should lie, always striving to find her own path to offer the best service and contribution to society. She also offered her skills and services in a voluntary capacity to the Middlesborough Survey along with several close friends with whom she had trained at the AA. The leader of this group was a very talented architect and planner Max Lock (1909–1988) who had been a contemporary of Mary’s at the AA and was now carving out a career for himself in urban redevelopment and participative planing. However, Lock fell deeply in love with Mary and naturally sought her returned affection, to no avail. He hoped for Mary to change her mind and throw in her lot with him for over a decade (1937–1946), once declaring ‘our friendship seemed to me, an unfinished monument.’34 Lock was a Quaker and argued in his many appeals for Mary’s affection, that this was among the many things that they had in common suggesting a potentially rich and rewarding partnership for life. They both had an understanding of the riches of Scandinavian design and appreciated the Swedish commitment to social welfare: Lock had been among the group from the AA who visited Stockholm in 1930 and he made a visit there again in 1937. Mary and he had become close friends and supported one another as pacifists as war broke out, when, as Lock remarked, ‘architecture seems such a second string to play at such time as this’.35

3.6 Mary Crowley with Max Lock, 1930s. IOE Archives, ME/A/8/1

For Lock, Mary’s presence and contribution to the Middlesborough Survey, brief though it was, was especially valued. He was ‘terribly impressed’ with the way she worked and ‘loved having’ her in the group.36 The cooperative working and skills sharing would have suited her well. Her gentle rejection of him as a possible husband and partner, in spite of all their common interests, background and political views, was clear and direct by this time but nevertheless, correspondence suggests some persistence on his part until at least the beginning of 1946.37

Lock never married. His letters make it clear that Mary was his chosen partner for life and he never found her equivalent.38 He was aware during these years of intense romantic interest that a major hindrance to his ambitions with Mary was her continued thwarted relationship with Laurin Zilliacus and he had hoped to save her from what he considered to be a source of great unhappiness. Finally acknowledging that they would remain lifelong friends but no more, Lock told Mary in a letter, ‘it has always saddened me to know you have had so much unhappiness, especially when it seemed you had everything else beside that one great satisfaction of your life’.39

The Middlesborough Survey proposed the building of primary schools to support the new estates planned for 28,000 people who would be housed over the following 15 years. Mary may well have influenced the parts of the report that described the provision of schools and the inadequacies of existing school buildings in the light of the 1944 Education Act.40 But while the survey learned from Mary, her involvement is also significant in the development of her own career as Lock’s practice worked as a multi-disciplinary collective, and sought to engage politicians and citizens with the planning process together with experts, something which also typifies the Hertfordshire project and later work at the Ministry of Education.41

Mary continued a close relationship with Bedales during the 1930s and 1940s and made regular visits. She continued to believe in its original progressive principles and derived strength in her convictions from those who continued with the school’s work. For a time, she was invited to make a more permanent home there through the invitation of Ken Keast, a teacher who had come to Bedales, on Mary’s advice, after suffering a traumatic experience supervising a group of schoolboys, several of whom had died on a school trip. Keast was also in love with Mary and seeing her as a future wife, appealed for her returned affection from the spring of 1936 until the outbreak of war but, as with the many suitors during these years, his hopes were thwarted.42

Continued contact with Bedales also provided a connection with the world of education, its contemporary progressive experiments and Modernist design. During the 1930s Mary regularly visited Bill Curry, a former teacher at Bedales and his wife Ena. On the day that war broke out she was staying with the Currys at their home, ‘High Cross’ at Dartington, near Totnes.43 Curry was then the head of the recently-established experimental school at Dartington Hall. The architectural style of the house proclaimed the headmaster’s values. It was modern with a strong orientation towards the future and international in both foundation and outlook. However, it was not Curry but rather John Newsom, also a mutual friend of Henry Morris and the Crowleys, who finally provided the opportunity for concentrated work in the field of education during the opening year of the war.44

Newsom just called at Sewells Orchard, found Mary sunbathing on the lawn and said ‘would you like to come and work on trying to do something about school meals in Hertfordshire Education Dept?’45

THE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL

a new piece enters the kaleidoscope.46

After almost a decade of unfocussed architectural work and some extensive travel in Europe, in 1941 Mary Crowley was recruited as an architect to work for Hertfordshire County Council by John Newsom, newly appointed Chief Education Officer. Newsom, ‘an educator who had never taught’ was a charismatic personality who was deeply interested in the possibilities of education in a new modern world where new art forms and communication technologies would help transform educational buildings and the teaching and learning taking place therein. As Stuart MacLure has observed, Newsom ‘believed with Henry Morris, that the child was educated by the whole environment in which he or she was taught, as well as by actual instruction. He wanted schools which elevated the spirit and ennobled the mind.’47

There was at the time no architect’s department at Hertfordshire County Council and Mary was recruited to the Education Department to advise on the provision of school kitchens.This was to become the beginning of a very productive phase and at the same time an end to a period in her life which was mainly dominated by housing projects and when, in her own words, she ‘didn’t do anything of real interest’. Newsom was a great friend of Henry Morris and would have been aware of the interest taken by Ralph Crowley and his daughter in the development of the Cambridgeshire community village colleges. His intention at the time was to bring together architects and educators to collaborate so that they would be ready to take up the historic challenge of post-war reconstruction. Perhaps he had also become aware, through his contact with the Crowleys, of the wartime progress in the USA of having educators and architects collaborate. Mirroring the same conviction held by Carlton Washburne, then Superintendent of Winnetka’s public schools, Newsom suggested ‘no architect should design a school until he has sat in a school for at least a week and seen what happens’.48

The immediate war-time work engaged Mary in helping schools to make arrangements for the feeding of school children and also some work on British Restaurants (pre-fabricated buildings). In 1943, the Government extended the school meal service which more than doubled the number of school canteens that were needed. Initially Mary worked in collaboration with the architect Paul Mauger based at Welwyn Garden City.49 Together, they travelled about to schools and helped them to set up small kitchens and dining areas. This brought her directly into village schools where the interest and knowledge she had already developed about advances in education gave her an eye for the work of inspirational teachers and led her to develop contacts with them. During the planning process, she, Newsom and the teachers she encountered ‘had discussions and thought about which way education was going and what was going to be built at the end of the war’.50 Such discussions were framed by an awareness of the very considerable achievements being made by the development of the village colleges in Cambridgeshire. This was a lively optimistic time when ways of working from within schools and in relationship with active teachers were developed.

Hertfordshire, as we have seen, was home to the Garden City movement that built Letchworth and Welwyn Garden Cities, both past homes of Mary Crowley and her family. This radical planning tradition rooted in the landscape, together with the demographic pressures of the post-war population boom, combined to create a very special situation where Hertfordshire was set to forge ahead with pioneering ideas about a new vision of school, especially for the younger child.51 ‘The atmosphere and circumstances of reconstruction offered a chance for that tradition to take a new turn’ and Mary ‘as a classic Herts progressive’ was perfectly placed to lead it.52

Mary’s progressivism was stimulated further by the circumstances of war and the close relationships with fellow left wing critics of the establishment to the extent that her Quaker faith was once again shaken. It is clear, from the correspondence that has survived, that Mary at this time considered joining the Communist Party of Great Britain. She may have been encouraged in this direction through working closely with the architect Paul Mauger, also a Quaker who decided to join the Communist Party. The Quaker theorist, Horace Pointing wrote Mary a lengthy letter to try to dissuade her from her decision to part company with the Quaker faith, supposing that it was maintaining a commitment to pacifism within the present circumstances that was troubling her.53 Certainly, she was closely involved with the impact of the conflict and in particular, her parental home at Welwyn Garden City had become a refuge for several Norwegian ex-patriots who had fled the ravages of their country. The dreadful destruction brought about by the German invasion of Norway must indeed have challenged Mary’s commitment to pacifism and the many friends she had who died or who were made prisoners of war during these years upset her greatly. Whether or not Pointing influenced her decision, Mary remained close to the Friends for the rest of her life and, though sympathetic, did not join the Communist Party.

The immediate aftermath of the war saw the opening of a new architect’s department at Hertfordshire County Council and the recruitment of a group of young, enthusiastic and committed architects who were keen to progress with the urgent task of meeting the school building needs of the community. Mary, working as an architect in the education department, and known to be the most knowledgeable and progressive mind about schooling available, was invited to join the team. She did so, but only after having considered giving up architecture altogether.

The new department was to oversee reconstruction, appointing C. Herbert Aslin as chief architect and Stirrat Johnson-Marshall as his deputy.54 Newsom, keen to grasp the opportunity to renew education through a school building programme, was at first inclined to employ private architects having a mistrust of municipal architects, probably regarding them as too conservative.55 In order to stimulate creative thinking and planning, he organized conferences and rather unorthodox informal gatherings to generate interest in new creative solutions to the post-war design of education. As Mary recalled, ‘he’d have a camp weekend somewhere peculiar on a heath and put up tents and cook our food and discuss things’.56 In such surprising circumstances, idealistic plans for the future were hatched. There was,

much thought and discussion about education in general and what to do about it, from nursery through to primary to what sort of secondary schools. There were occasional conferences and the freedom to visit and discuss with teachers in action.57

Soon the Architect’s Department took over general responsibility for school building and new recruits included outstanding architects and designers already known to Aslin and Johnson-Marshall including David Medd and James Nisbet (1920–2009), the quantity surveyor who famously invented cost planning.58 These were all keen to prove Newsom wrong and demonstrate how in-house teams could be a progressive and efficient force for change. Mary agreed to join the group but only after taking a six month trip to the north of Norway between June and October 1946 where she was to visit old friends and help in the reconstruction of the country’s infrastructure.

In Norway, Mary had been invited to accept employment as an assistant architect to be posted either at Harstad or Finnmarke with an allowance of 600 Kroner per month plus travel expenses.59 Removing herself from England and immersing herself once more in Scandinavian culture, language and landscapes gave her an opportunity to realize once again that part of her identity and to think over some important decisions as to where her career should lead and with whom she should share her life. It may have not been coincidental that Mary reached her 40th birthday in Norway and while she did not publicly celebrate the day, and kept its significance to herself, its passing surely must have given her cause to reflect.

After the experiences of the war years in London, the sojourn in Norway was refreshing and delightful and although she was there to work and advise, her diary records much enjoyment in the social atmosphere among friends and of the natural vistas of the north. To begin with, it was not at all clear where she would be heading and what she would be required to do, and it was ‘all rather terrifying as I have been separated from anything English’, especially as, ‘meeting new people and unknown work is apt to frighten me’.60 Her contacts and guides were Diderich and Sigrid Lund, members of the War Resisters International. Sigrid Lund had, like Mary, assisted with the transportation of children at risk during the war years and she had in the process become a Quaker. Mary spent most of July in Harstadt with much relaxing and chasing the midnight sun, noting with delight particular nights in the month when the sun appeared to ‘dance’ on the horizon. But later she was sent to join one of the several colonies of architects, engineers and other specialists working in different parts of the country. Towards the end of her time away from England, she revisited the city of Stockholm which held so many memories for her. There is evidence in her travel journal that she was wondering whether or not to settle in Scandinavia and find work there. But she may have sensed the possibilities of finally engaging with work in England that took her over and allowed her to truly offer her talents and knowledge and she confessed that while she found it ‘lovely, just to have a look at it again’, she knew she would ‘not be happy to live’ there. But she acknowledged the achievements of Sweden for infrastructure and social services, declaring them ‘the one hopeful spot in Europe’.61

The time away enabled Mary to reflect carefully on where her future should lie and she even began to have doubts as to whether her talents were best employed in architecture at all. She was as ever pulled towards education, the development of which she saw as the essential hope of humanity. On her return from Norway, toward the end of 1946, Mary reconsidered her decision to move to the Hertfordshire Architects’ office. She seriously considered, before rejecting, an offer she had received to take up a post at Bedales school as housemistress, taking the place of a long serving member of staff and old friend, Miss Hobbes. Clearly, the world of education was competing with architecture for Mary who was committed to them both equally. Such a move, had she made it, may have brought her closer to a potential marriage with the Bedales housemaster Ken Keast and would have destroyed the hopes of other suitors at the time. A female friend, in whom she confided, thought the decision against moving closer to education was a wise one even though she acknowledged that Mary would have put her whole being into the role. ‘I know you would have become absorbed in first hand education and perhaps the most important – that the human side of it would have brought you much riches.’62 Bedales would have benefitted too. Mary received a letter from the then principal of Bedales, H. B. Jacks, appreciating her ‘wise decision’ and also appreciating how close the school had come to recruiting an invaluable new member of staff, with all the right credentials and understanding of the school’s progressive ideology. However, he told her, ‘if you had decided otherwise and come here, I might have found it difficult to resist a feeling that I had been responsible for taking you from a sphere to which you rightly belonged’.63

During the same year that she joined the Hertfordshire Architect’s Department in 1946, the first staff inspector for primary education, Louis Christian Schiller (1895–1976) was appointed, a move that was to prove very important for Mary and other like-minded progressives who wished to see the promise of the Hadow Reports of the 1926 and 1931 fulfilled.64 In sum, these reports had argued for a new view of the child in the school environment, fitted to its stage of development and towards an education for the younger child characterized by learning through activity and direct engagement. Such a view seemed to suggest an entirely different kind of environment for the young child from the Victorian elementary school that still predominated in villages, towns and cities. The 1936 Education Act had confirmed the government’s commitment to educational reorganization and increased capital expenditure from a low level of £3.3 million in 1933 to £14.5 million in 1937.65 Therefore, what might be regarded as a constellation of factors came together at the time to create the image of the new primary school. As HMI Christian Schiller later reflected,

when in 1945 Primary schools became a statutory part of our national system of schooling, there came a group of new architects just ready to create a new sort of home for this new sort of school … Their appearance changed the whole pattern of thinking and doing, as when a new piece enters the kaleidoscope; instead of trying to assess the needs of young children in terms of square feet or floor space, we began to talk of working spaces, noisy spaces, a quiet home space, an environment in which children could live and learn.66

Mary Crowley was one of the key parts of the kaleidoscope identified by Schiller at the start of his career in shaping the ethos and identity of the new primary school. They became friends and colleagues for the rest of their respective careers.

The new Hertfordshire team of architects, once established, worked together in one room in the basement of County Hall and thereafter followed a frenzied period of activity to design schools, fast and cheaply while meeting the needs of the best teachers and all of the children. This group have been rightly recognized as making significant advances in the technical solutions of system building. But first, they were to ponder the question, ‘what is a school?’ Mary along with the primary school advisor Percy Munsey, would provide the answers and crossing over from the education to the architect’s department, her ‘unique background and talents were to make her, over the years, the greatest single influence on the planning of the post-war schools’.67 ‘We had to start again and we knew that something we were searching for was something new and refreshing, and the more we became familiar with the educators’ aims, the more stimulating the architectural character would be.’68

Mary was interested in education as a process and an experience and she was aware from her work in schools during the war of what teachers, inspired by the changes in policy suggested by the Hadow Reports, were attempting through improvization inside schools. An enlivened education was becoming established in classrooms and corridors in spite of cramped and restricted conditions. Through a close observation of their practice it was possible to see where they were heading and therefore what conditions were suited to their needs. But of course the vast majority of teachers were not experimenting to this degree and for architects to follow Newsom’s call to observe schools in operation in order to increase their understanding of how to design a modern school, it was important that they be directed to the better examples. For this they relied on the guidance of HMI.

3.7 Mary working at Hertfordshire Architect’s Department, 1946. DLM personal collection

Wise educators of experience would introduce architects to leading practitioners in selected schools, where new ways of learning were developing. It was not the building they went to see and to imitate, it was the teachers and children – the things they were doing, the materials they were using, the groupings and the comings and goings; the imaginative ingenious arrangements and improvisations of space and equipment, the home-made bits and pieces; the animals and plants, the displays of children’s work alongside that of professional artists and craftsmen.69

There was a similar message coming from across the Atlantic. In 1942, the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted an exhibition on architecture and the modern school. The curator, Elizabeth Mock explained the purpose of the exhibition was to show how schools should be designed with regard to children’s psychological and physical needs and be ‘a place where the child can feel that he belongs, where he can move in freedom and where he can enjoy immediate contact with the outdoors. For these reasons, the modern school should be a rambling, child-scaled one story building, gay and friendly, direct and unpretentious.’70

David Medd, who had originally wished to become a furniture maker, was also interested in the interiors of school spaces but with ‘a different tack – furniture, acoustics, colour and lighting’ Later in life, he observed, ‘this may have been one of the aspects that brought us together!’71

In technical terms, the key to post war development in school architecture was the use of prefabricated parts or standardized components and that part of the story has been told thoroughly by others and will not be considered in detail here.72 The pre-war schools had been built one by one but due to lack of traditional building trades in the immediate aftermath of war, the Hertfordshire team opted for prefabrication which demanded a programme of at least a year’s worth of schools to be developed at once. As Guy Hawkins, a colleague of the Medds later at the Ministry of Education has put it, ‘The resulting lightness of construction also generated a lightness of spirit that was not only more pleasant, welcoming, and humane than previous formally planned brick schools, but also said ”New” … ”Different” and indicated clearly that new, and attractive educational possibilities lay within.’73 The impact of the Hertfordshire team’s innovations in engineering was long-term and widespread. By 1970, 41 per cent of school building in the UK used such methods.74 In the words of David Medd, this meant that ‘components that could be carried by two men were standardized on a dimensional basis which allowed them to be assembled in a variety of ways to meet different topographical and educational needs’.75 While architects such as David Medd committed years of their lives to perfecting systems building by working very closely with manufacturers, the Medds collectively also recognized that the increased flexibility offered through prefabrication enabled their view of an altogether different educational landscape to be realized. However, it is noticeable that they reverted to traditional methods in the schools they were most closely involved with during the 1950s and 60s.

Mary’s connection with Scandinavia and her appreciation of the qualities of design in those countries chimed with a growing enthusiasm among English architects for Swedish influences. In 1943, The Architectural Review published a special issue entitled ‘Swedish Peace in War’ in which the editors presented Sweden as a model to follow in reconstruction where ‘most public buildings, especially the smaller accessory ones, are pleasant, light hearted, almost playful, and yet strictly contemporary’.76 But there was also the influence of innovation coming from across the Atlantic and later the Medds acknowledged how much of an impact the work of the architectural firm Perkins, Wheeler and Will had made on their own planning. Of Crow Island School, Winnetka, Illinois, they explained,

the collaboration between ‘education’ and ‘architecture’ which brought it into being and the educational philosophy behind its design had a direct influence on some of the early post-war school design in Britain.77

The first batch of schools built in Hertfordshire after the Second World War and opened between 1948 and 1954 were celebrated in a publication, A Hundred New Schools published by the County.78 The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner recognized the significance of these early primary schools in his 1953 Hertfordshire volume, part of the series The Buildings of England. He celebrated the achievements of the designers where, ‘from the balancing of block against block down to the colours of the walls, the curtain patterns and the door handles, everything is carefully considered and elegantly done. It is a delightful experience to walk around and through some of these schools.’79

3.8 Crow Island School, Winnetka, USA, March 1941. Copyright Cranbrook Archives, Richard G. Askew, photographer, 5657-8

Before Mary moved to work for the Ministry of Education in 1949, a number of schools were built or near completion that she and her future husband David Medd worked on as part of the Hertfordshire Architects’ team. Tracing Mary Crowley’s hand at this time within the Hertfordshire Architect’s Department is not a straightforward task as teamwork was so strongly developed and adhered to. This way of working was a ‘moral ideal’ where ‘anonymity of the designer within the group and the sharing of research between all parties involved’ mattered more than individual achievement.80

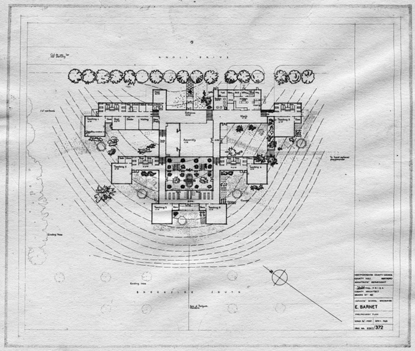

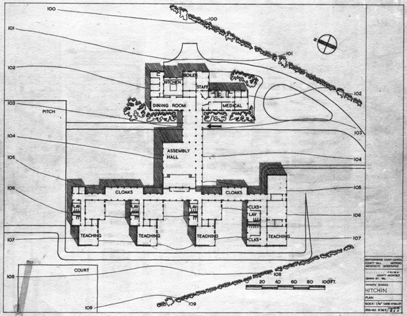

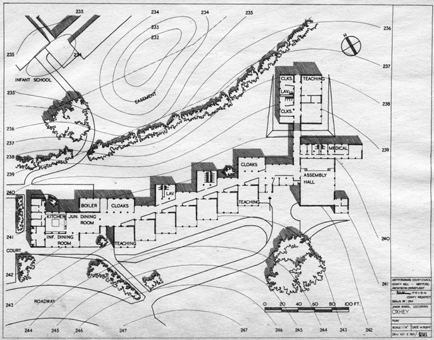

The new schools were mostly for younger children. They were Burleigh Primary School, Cheshunt (1946, listed 1993) with an additional junior department, opened by R. A. Butler in 1948; Malvern Way Junior School, Croxley Green Junior School, opened in 1949; Essendon Village School (1948, listed 1993); Templewood School, Welwyn Garden City (1950, listed 1993); Morgan’s Walk, Hertford (1950, listed 1993) and Aboyne Lodge Primary School, St Albans.81 In addition to these schools, Mary Crowley worked on Strathmore School, Hitchin (1947–1949 with John Redpath); Colnbrook School, South Oxhey, Watford (1947–1949, with Bruce Martin); Warren Dell School, South Oxhey, Watford (1947–1949, with Bruce Martin); Monkfrith School, East Barnet (1949–1950, with Oliver Cox) and Cowley Hill School, Borehamwood (1949–1950, with A. R. Garrod).

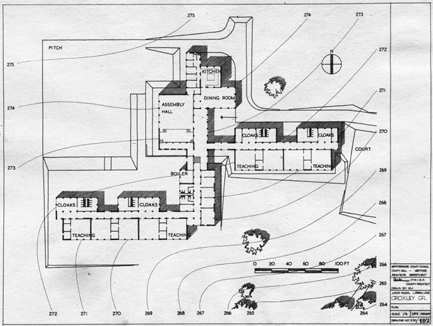

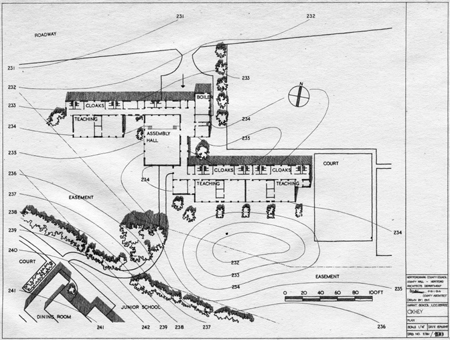

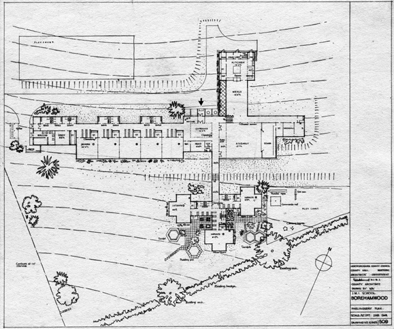

Collectively these schools were recognized nationally and internationally as making a break with the past not only in their arrangements for teaching the curriculum but also in their lightness of atmosphere and sense of space and in the degree to which respect for the individual child and their immediate needs was evidenced. The plans for Strathmore School (Fig. 3.10) and Croxley Green Junior School (Fig. 3.12) show clearly how a de-institutionalization was sought by means of each school class having access to its own teaching space and adjacent cloakrooms. The plans of schools such as Boreham Wood (Fig. 3.14) and Aboyne Lodge (Fig. 3.13) St Albans show the degree to which the original planting and landscape was considered and the value of the outdoor environment in general.

As a direct result of the leadership of John Newsom there was, at this time in Hertfordshire, a tremendous sense of artistic and political opportunity that the architectural historian, Alan Powers has described as ‘the Gropius philosophy of architecture in action’.82 David Medd agreed with this analysis.

I could not help feeling that in Herts in those days, under the Atlee government, we were closer to fulfilling Bauhaus ideals than Gropius was in the political climate he endured re employing modern techniques (however primitively) for large scale social programmes, which combined the contribution of architects and artists.83

3.9 Plan East Barnet Infants School. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

3.10 Plan Strathmore Avenue Infants School, Hitchin. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

3.11 Plan Oxhey Junior School. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

3.12 Plan Croxley Green Junior School. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

3.13 Plan Aboyne Lodge Junior School, St Albans. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

3.14 Plan Boreham Wood Junior and Infants School. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

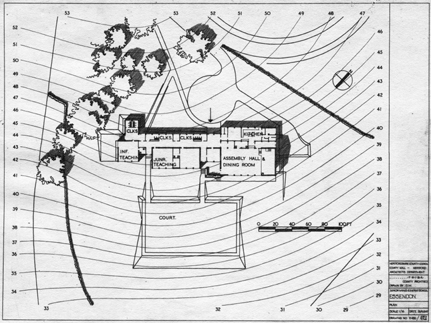

3.15 Plan Essendon School. IOE Archives, ME/D/5

In 1948, just as these schools were opening, the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) chose to hold their conference at Hoddeson, not far from Cheshunt in Hertfordshire.84 This was the occasion when several important architectural modernists were able to visit the schools and commented on them. Le Corbusier, visiting Templewood declared it to be ‘très jolie’ while London County Council architect Bill Howell said that ‘walking through a Herts school is like walking through a sequence of 8′ cubes’ and the architectural writer and photographer Kidder Smith also enjoyed the schools.85 Bruno Mathsson, the Swedish furniture designer and Walter Gropius was part of the group and David Medd recalled that he was required to fill Gropius’s ‘neat leather box’ with slides of the schools, ‘no doubt for his schools work he was soon to do in Cambridge Massachusetts’.86 What the visitors witnessed were the results of a new technique designed to solve social problems, including the work of artists ‘just as the Bauhaus used to proclaim, but was not possible to put on the ground in pre-war continental Europe.’87

A common characteristic of these schools was their respect for the role of the outdoor environment in children’s experience. The mature trees on site were preserved as far as possible so that the buildings appeared to grow around them or nestle among them. Mary would have known the name of every tree and bush on site and would have expected this knowledge to be passed on to children as part of the curriculum. Of course she also expected the children would find the trees provided welcome shade in the summer and play materials in the autumn.

Accounts of the development of the Hertfordshire schools have to date concentrated mainly on the advances in engineering and particularly in the use of prefabricated standardized parts.88 This was highly innovative and significant in a post-war economy that was severely stretched in terms of resources and demand. Here, I will concentrate on what Mary Crowley in particular brought to planning and examine this through accounts of the development of a selection of Hertfordshire schools from this period.

BURLEIGH PRIMARY AND INFANTS SCHOOL, CHESHUNT (1946–1948)89

The autumn of 1946 saw the beginning of close cooperation between the Hertfordshire Architect’s Department and the Ministry of Education. The first project was to be the Burleigh Primary School at Cheshunt. Designed for 320 pupils between 5 and 11 years and 9 staff, the infant wing of the school was to act as a first of its kind so far as construction was concerned. The planning took the form of envisaging how three separate prefabricated units, each a small ‘home’ for a group of children with its own garden court, might perform.90 The design of the component modules of 8 feet 3 inches providing square classrooms of 24 foot sides was the responsibility of the manufacturer – Hills and Co. The inspiration for the notion of how this might work in practice was Mary’s, working with David Medd and Bruce Martin on the job. Mary later suggested that the idea came originally from a school near Stockholm that she had visited on her recent return journey from the north of Norway.91

Coming back from Norway – there was a conference or other in the woods and there was a marvelous little school all in individual houses about the trees and obviously this idea came to me about this infants school because I knew enough about infants schools at that time and individual teachers – some teachers were about doing marvelous work at that time since before the war through the war and after the war – and so I thought a little home, like I saw in the woods – but it had to be a separate little home with own lavatories and things and classrooms – the simplest possible thing you can have with its own little garden court and another and another … in Cheshunt of course it was just a corridor but that’s obvious where it came from – from Scandinavia.92

We know from Mary’s diaries that this school was in fact Vyggbyholm Skolan, north of Stockholm, in Sweden. This experimental school was founded in 1928 by the leading educational pioneer in Sweden Per Sundberg known as an educational reformer, humanitarian and leader of the Quakers in Sweden. It must have been the Quaker connection that led Mary to visit Vyggbyholm on her journey home. Here she discovered a school for about two hundred children divided into ‘houses’ of about 20, each with a married couple or housemother. There was a central hall or dining room and separate houses for crafts, ‘all delightfully scattered amongst the trees with no sense of an institution’.93 There was a particular attention to craft and handwork at the school which was sponsored by the architect Carl Malmsten (1888–1972). There are several images of the school kept by Mary over the years in a brochure showing children in the wooded outside environment of school buildings displaying a homely character. Translating such a rich environment into the prefabricated dwellings at Cheshunt takes some imagination however it was the essence of belonging to school as one would to a home that was Mary’s inspiration.

3.16 Children on the forecourt of Burleigh Primary and Infants School, Cheshunt, Hertfordshire. IOE Archives, ME/D/22

3.17 Vyggbyholm Skolan, near Stockholm, Sweden. IOE Archives, ME/G/26/2

Breaking up the monumentality and institutionalized image and form of the school as it had become was the major achievement of the first schools built by Hertfordshire and Mary’s influence was telling. Staggering individual blocks and thus breaking up the whole became a preferred way forward.94 This had positive effects on the quality of light that was made possible and allowed for the beginnings of establishing more variety of possible seating arrangements where ‘children could comfortably take part in activities facing in different directions, rather than all be turned towards the chalkboard.’95 At Cheshunt Infant School, the team designed three staggered sloping roofed classrooms, separated by planted courts, painted white. The mono-pitched roofs resembled the roofs of the three houses at Tewin that Mary had designed a decade earlier and projected the same Scandinavian tone that had been established there. Many of the ‘ingredients’ of planning that she was later to consolidate in work for the Ministry of Education were already present.96 Each classroom had easy access to the outdoors and each unit was provided with its own washroom, W.C. and coat store. This was the first demonstration of design on a standardized structure ‘plus colour, plus, heating, plus furniture, plus lighting plus educational thinking – and the whole based on its users – children, teachers and what they were doing and needing’.97 The final group of buildings was considered a study in simplicity and economy. The classrooms, according to Andrew Saint, ‘preserve a crisp, pioneering, Swedish quality which few later schools captured again’ and provided a link with the pre-war achievements of the open-air and nursery schools movements.98

Though simple and unpretentious, the classrooms were inspiring to other architects keen to learn of the new possibilities of designing school environments. Henry Swain, later County Architect for Nottinghamshire, said of them, ‘there was a total unity of architectural and technical thinking’. But for Mary they represented the beginnings of provoking alternative pedagogical possibilities. David Medd pointed out that the school design at Cheshunt was strikingly similar to an illustration of a classroom for children at Crow Island School in Carleton Washburne’s A Living Philosophy of Education (1940) whose work Mary valued highly. The plan gave each group of forty pupils their own entrance, own sanitary facilities, workrooms and garden court. ‘It had a social aim from the start; not a number on a door in a corridor.’ This set the scene for other early schools in Hertfordshire and later for the Ministry of Education.99

Both Cheshunt and the second Hertfordshire school at Essendon, were inspirational to others also seeking to exploit the post-war demand for new school places to achieve a step change in school building design. Henry Swain remarked,

I can’t impress on you too much how different these buildings looked. Seen in the context of the Modern Movement, everything monstrous and big and reinforced, here was something light and delicate and hammered out of the process of studying the problem. It was totally new. It didn’t seem to have its roots in anything… It was simply the artefact to do the job, but that job included the care of children.100

It was the latter – understanding what it meant to care for children in educational contexts – that Mary brought to the task along with her rich reservoir of knowledge and international awareness of developments in New Education. Learning from Mary’s presence in the team, David Medd realized the need for components to provide for more flexibility in use and spent several months in 1947 after Cheshunt had been completed, working with Hills, a construction firm based at West Bromwich, to develop the system. This process was repeated annually as more schools were completed thus establishing a pattern for development involving architects, manufacturers and users, a pattern that was to pay dividends later for the Ministry of Education.101

TEMPLEWOOD PRIMARY SCHOOL, PENTLEY PARK, WELWYN GARDEN CITY, HERTFORDSHIRE (OPENED 1950, RIBA BRONZE MEDAL 1952; LISTED 1993) ARCHITECT A. W. CLEEVE BARR102

Pentley Park School (later Templewood) was designed for 200 junior and 120 infant children and was built between 1948 and 1950. The school is important to consider in relation to the Medds since it articulated the principles outlined in Building Bulletin 1, ‘New Primary Schools’ (1949) where individual teaching spaces extended outdoors via a paved terrace linking inside and outside and emphasizing the small scale appropriate to primary aged children. Here, Mary’s ideal environment noted during her time in Scandinavia of a series of houses nestling in the woods was realized in her home town of Welwyn. The school was scaled to the body of the primary school child to ensure a close fit and a strong sense of belonging. Doors and windows were designed to be accessible and easily operated by small children. Circulation spaces were designed as extensions to the teaching areas reflecting awareness of how some of the more imaginative teachers in the country had begun to use spaces outside of the classroom to carry out project-based learning.103 Each classroom was envisaged as a self contained ‘home’ with its own lavatories and cloakrooms.

3.18 Children playing in the school grounds at Templewood School, early 1950s. IOE Archives, ME/D/22

The site architect at Templewood was Cleve Barr however the design of the school and school grounds reflect educational thinking and planning of the Hertfordshire team and of CEO John Newsom. The layout was essentially a series of staggered arrangements of work spaces linked to extensive corridors offering opportunities for large scale work, construction or group work as well as easy access to outdoor terraces through glazed doors. Windows were extensive and classrooms were furnished with polished concrete window-ledges assembled at child ‘perch’ height around the edges, resembling in concept if not in materials the window benches at Crow Island School, Winnetka. In the infants’ play area, carefully scaled wooden benches were built in as permanent features driven by an image of children of various heights at ease in the outdoor environment occupying the benches while playing restfully. In the grounds immediately outside of the head teacher’s office there was a pond and terrace area placed next to a mature oak tree that was carefully preserved.

The school buildings were grouped around a central hall with an impressive stage and separate dining area, each decorated with large murals produced on site by the artist, Pat Tew (Fig. 3.19, Plate 1). Based on Russian fairy tales, the murals offered a lively colourful stimulus for teachers of art and literature to utilize. The deep red of Tew’s background on the murals positioned either side of the entrance to the main hall reflected the deep red tone of the outer school wall panels. In sum, Templewood, set among woodland, was a light, bright and colourful, carefully-scaled primary school that contrasted markedly with the pre-war image of a school for young children. It represented the best example to date of a school for young children set in a rich landscape and interpreting child-centered education drawn from Europe and the USA.

3.19 Pat Tew’s murals, Templewood School, Welwyn Garden City. Photograph courtesy Soo Hitchin

ABOYNE LODGE, NURSERY AND PRIMARY SCHOOL, ST ALBANS, HERTFORDSHIRE (OPENED 1950, LISTED 2010)104

This school further developed and benefitted from the flexibility offered by standard components first realized at Burleigh Primary School, Cheshunt. As was the case at Templewood, the site offered a rich opportunity to embed the school buildings neatly into an established landscape – in this case an apple orchard. The site, near the centre of the town was rich in natural resources which were preserved so that the various single story buildings appeared to nestle comfortably into the landscape. The grounds of the school were rich in trees and the school originally contained a sculpture ‘Tobias’ by Daphne Henrion.

As the image (Fig. 3.20) makes plain, the view from the inside out was a significant aspect of the overall design and the large window components emphasized this here and in many schools built by Hertfordshire and the Ministry of Education thereafter.

3.20 Entrance from the interior of Aboyne Lodge, early 1950s. IOE Archives, ME/D/4

NOTES

1 MBC, British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2, 7 September 1998.

2 J. Pritchard (1984) View from a Long Chair. The Memoirs of Jack Pritchard. London. Routledge Keegan Paul. p. 29.

3 Herbert Read (1893–1968) was a key intellectual in this respect.

4 David Medd and Mary Medd, ‘Designing Primary Schools’, The Froebel Journal (1971) p. 6.

5 Malcolm Reading (1986) A History of the M.A.R.S. Group 1933–1945: A Thematic Analysis. Reading. S.I.

6 Godfrey Samuel Papers held at RIBA/V&A Archives. SaG/90/2. MARS Group circular letter, September 1933; Minutes of Central Executive Committee meeting, 2 June 1937. I am grateful to Elizabeth Darling for these references.

7 Fry (1975) p. 15.

8 Elizabeth Denby was a significant figure in the design community during these years. She had wanted to become an architect but her work was confined to advising on public design projects. The 1930s was a decade that saw the doubling of the number of nursery schools in England, mostly through the successful campaigning of the Nursery School Association which had been founded in 1923.

9 A. Powers (2007) pp. 66–7.

10 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2, 7 September 1998; for Denby, see E. Darling‘Kensal House: the Housing Consultant & the Housed’, British Modern: 20th Century Architecture, 8 (2007) pp. 106–16.

11 K. Worpole (2000) Here Comes the Sun. London. Reaktion Press. p. 59. The Peckham Heath Centre (1935–1950) was a scientific experiment, community centre and school.

12 The Peckham experiment was founded by George Scott Williamson (1884–1953) and Dr Innes H. Pearse (1889–1978).

13 ‘The Peckham Experiment’, The Pioneer Health Foundation website. http://www.thephf.org. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

14 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2, 7 September 1998.

15 MBC diary, 1933. ME/A/4/36.

16 J. M. Richards (1940) An Introduction to Modern Architecture. London: Penguin.

17 A. Powers (2007).

18 Memoirs of Bill Miall, http://prism.bham.ac.uk/~rcm/private/WEM_memoirs.pdf. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

19 BL Brodie interview manuscript, p. 19.

20 Building Centre Committee (1936) Housing: A European Survey. London. London County Council; A. Powers (2005) p. 98; J. Gould (1977) Modern Houses in Britain, 1919–1939. Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain. p. 65.

21 Margaret Justin Blanco White (1911–2001).

22 Lynne Walker, (1997) p. 22.

23 See http://designmuseum.org/design/the-mars-group. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

24 Walker (1997) p. 24.

25 A. Saint (1987) p. 50; A. Powers (2007) p. 48.

26 M. Dudek, (2000) Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments. London. Architecture Press. p. 79. See also M. Dudek (2000) Kindergarten Architecture. Space for the Imagination. London. Taylor and Francis.

27 DLM typed notes on MBC, 17 June 2005.

28 Other architects who participated included Max Lock with Judith Ledeboer, Wells Coates and Serge Chermayeff.

29 Building Centre Camp Competition – Summary. ME/A/7/4.

30 The Architect’s Journal, 13 July 1939. p. 82; The Architect and Building News, 2 June 1939.

31 See Harry Ree (1966) Educator Extraordinary: The Life and Achievement of Henry Morris, 1889–1961. London. Peter Owens Publishers.

32 Susan Charlton, Elain Harwood and Alan Powers (2009) British Modern. Architecture and Design in the 1930s. London. The 20th Century Society. p. 72.

33 The Wren Society, Volume 17. Vol XVII (1940). MBC worked for a while in Jellicoe’s offices in the spring of 1934. ME/A/4/37.

34 ML letter to MBC, 5 September 1944. ME/A/8/6.

35 ML letter to MBC, 16 September 1939.

36 ML letter to MBC, 12 April 1945.

37 ML letter to MBC, 19 January 1946.

38 ML letter to MBC, 5 September 1944.

39 ML letter to MBC, 5 September 1944.

40 Middlesborough Social Survey (1945) p. 14.

41 I am grateful to Professor Roy Kozlovsky for this observation.

42 Ken Keast letters to MBC, 1930s. ME/A/8/4.

43 ‘High Cross’, designed in 1933 by the Swiss-American architect William Lescaze, was said to be one of the few ‘purist’ Modernist houses in England, associated with the name of Le Corbusier. Country Life (1933). Lescaze also designed a boarding house for the school at Dartington, A. Powers (2007) p. 58.

44 For John Newsom, see David Parker (2005) A Hertfordshire Educationalist. University of Herts Press.

45 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 2, 7 September 1998.

46 C. Schiller, Introduction to ‘Designing New Primary Schools’, The Froebel Journal (1971).

47 S. Maclure (1984) Educational Development and School Building: Aspects of Public Policy, 1945–73. University of Michigan. Longman. p. 45.

48 A. Saint (1987) p. 60.

49 Paul Victor Edison Mauger FRIBA (1896–1992).

50 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 3.

51 A. Saint (1987) pp. 58–9.

52 A. Saint (1987) p. 61.

53 Horace Pointing letter to MBC, 2 September 1942. ME/A/8/5.

54 C. G. Stillman was initially appointed Chief Architect but moved on quickly to Middlesex to take up the same post there.

55 DLM (2009) p. 4.

56 British Library Architects Lives. Tape 23, 7 September 1998; Saint (1987) p. 62; MacLure (1984) p. 40.

57 MBC ‘Some rough personal notes’ in preparation for BL interview, August 1998.

58 James Nisbet, obituary ‘best known for inventing the elemental cost plan in the fifties while tasked with cutting school building costs by 50% at Hertfordshire council’ http://www.building.co.uk/news/revolutionary-qs-james-nisbet-dies-aged-89/3142003.

59 DLM notes on MBC, IOE Archives Medd Collection, 2005.

60 MBC diary, 26 June 1946.

61 MBC diary, 29 September 1946.

62 Ruth (Manchester) letter to MBC 8 June 1947. ME/A/8/5.

63 H. B. Jacks letter to MBC, 30 May 1947.

64 For the Hadow Reports see Derek Gillard, The History of Education in England http://www.educationengland.org.uk/articles/24hadow.html. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

65 S. Maclure (1984) p. 5.

66 Schiller (1971) Introduction.

67 DLM (2009) p. 9; A. Saint (1987) p. 64.

68 DLM (2009) p. 19.

69 David and Mary Medd (1971) p. 7.

70 Ruth Mock, Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 1942 press release. http://www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/821/releases/MOMA_1942_0063_1942-

09-24_42914-57.pdf?2010. Accessed: 29 August 2012.

71 DLM letter to author, 21 August 2006. Hertfordshire Architect’s Department designed the first range of colours for a building programme, transformed into the Archrome Range by MOE Building Bulletin No 1 (1949) and was the same range of colours used by the Festival of Britain (1951). Became base of the British Standards Range BS4800 still in use today.

72 The best account is Andrew Saint (1987) Towards a Social Architecture.

73 Guy Hawkins, correspondence with author.

74 P. Cunningham, (1988) Curriculum Change in the Primary School Since 1945: Dissemination of the Progressive Ideal. London. Falmer Press. pp. 142–3.

75 DLM notes on early post war systems of construction, 22 February 1965. ME/D/4.

76 W. Holford, ‘The Swedish Scene: An English Architect in War-Time Sweden’, The Architectural Review, September 1943, p. 59.

77 ‘Schools in the USA’, BB, 36, p. 46.

78 Hertfordshire County Council (1954) A Hundred New Schools.

79 N. Pevsener (1953) The Buildings of England. Hertfordshire. London. Penguin Books.

80 A. Powers (2007) p. 50.

81 The Architects’ Journal Feature 12 May 1960. pp. 731–40; Architectural Feature, Public Opinion, 8 June 1951. pp. 13–15; ‘Architectural Review: The Herts Achievement’, Architectural Review, 111, June 1952. pp. 366–87.

82 A. Powers (2007) p. 50.

83 DLM (2009) p. 18.

84 The CIAM was founded in 1928 and disbanded in 1959. Its purpose was to promote architecture as a social art.

85 The group visited Burleigh, Essendon, Templewood and Aboyne Lodge schools. DLM, 2009. p. 2.

86 DLM (2009) p. 18.

87 DLM (2009) p. 2.

88 The major work in this respect is Andrew Saint (1987) Towards a Social Architecture. New Haven and London. Yale University Press, and Stuart MacLure (1984) Educational Development and School Building. Harlow. Longman. pp. 37–60.

89 Maclure (1984), p. 58; 148; Saint (1987) p. 49; C. H. Aslin, ‘Specialised Developments in School Construction’, The RIBA Journal, September 1949 & November 1950; Architectural Review, February 1947; Architect and Building News, 16 January 1948; 13 September 1949, pp. 319–26; The Times, 24 July 1948.

90 As Andrew Saint makes clear, the units were shells already in existence as experimental 8 feet 3 inch classrooms constructed by Hills and Co of West Bromwich. Saint (1987) p. 65.

91 To Norway – Finnmark around to Kirkenes and back to Harstad. MBC personal rough notes, BL. August 1998.

92 British Library Architects Lives, 1998.

93 MBC diary, 29 September 1946.

94 A. Saint (1987) p. 80.

95 A. Saint (1987) p. 90.

96 MBC developed the five ingredients of planning in schools. These were: a home base; an enclosed room; a general work area; particular bays; and a veranda or covered area.

97 DLM rough notes on MBC, IOE Archives, Medd Collection, p. 11.

98 A. Saint (1987) pp. 71–2.

99 DLM (2009) p. 11.

100 A. Saint (1987) p. 75.

101 A. Saint (1987) p. 65.

102 Architect and Building News, 30 September 1949; The Architects’ Journal, 27 March 1952; Architectural Review, June 1952; Richard Llewellyn Davies and John R. Weeks, ‘The Hertfordshire Achievement’, The Architects’ Journal, 20 October 1949; Malcolm Seaborne and Roy Lowe (1977) The English School, Vol 2. London. Routledge Keegan and Paul.

103 An example is found in a highly influential elementary school in Birmingham, recorded in ’Story of a School’ Ministry of Education Pamphlet No 14, HMSO, 1949.

104 MacLure (1984) p. 152; The Architects’ Journal, 12 May 1960, pp. 731–40; Public Opinion, 8 June 1951.