10

FLESH OF STONE

Buildings, statues, entangled bodies

Tracey Eve Winton

Gods in Antiquity were bodily things. The Druids worshipped oaks; Egyptians worshipped animals; shapeless stones were venerated by the Greeks, and the Sherpa reverenced Mount Everest as their mother goddess. Hindu avatars and the mass of the Roman temple testify that invisible powers need bodily presence to dwell and act in the world. As conscious persons we identify ourselves with our corporeal flesh, which furnishes us with our finite limits and carnal pleasures. Our awareness, though, involves a world beyond the body’s limits. The flesh of the world and of others is sentient and responsive, vulnerable to our words and thoughts, especially to our desirous gaze and touch. I’d like to turn to the Hypnerotomachia,1 to which Alberto Pérez-Gómez first introduced me, and read out a poetic understanding of man’s intertwining with architecture.

In the Hypnerotomachia’s text and images, published at the height of Renaissance naturalism, embodiment is inseparable from thought’s phantasmic imagery. Poliphilo frames his vision of rarefied philosophical and theological ideas concretized in symbols with an ekphrasis of the world coming into physical being through the rising Sun, in the Spring as a time of universal rebirth. He dreams, and within his dream he dreams again: a Neoplatonic symbol for liberating the contemplative soul from bodily needs. Yet in this dream, his body and its organs haunt him in every scene. He missteps and trips over roots, stones, shards, and uneven ground; he suffers from thirst and exhaustion; he endures shame for being scratched and dirty; he sweats; he sighs, he eats; he grows aroused and blushes. In short, he brings his body with him.

Both woodcuts and text present types of heads and bodies, ranging from portraits and icons to the aniconic: tree trunks, nymphs, topiary or mineral statues, free-standing or in bas-relief, classical columns and capitals, obelisks, fountains in human form, funerary masks, hollow armor, grotesques, flat encaustic wall-portraits or fleeting reflections in mirrored surfaces, nuancing the continuum between Poliphilo as perceiving subject and the architectural objects of his desire. In all its variants, the statue – imago hominis in architectural matter – is the primary symbol of this space of exchange.

Figure 10.1 Poliphilo in the ruins of the ancient city. The limbless torso of a statue lies juxtaposed with a column capital

Architectural form, though organized by geometry and abstract qualities, is attributed animate features. Poliphilo’s vocabulary revives arcane Latin and Greek terms that depict architectural elements as organic tropes and, supported by ornamental statuary and carvings on the buildings’ visible surfaces, reveals that buildings have living parts: divine, monstrous, spiritual, human, animal and vegetal. The word he uses for “frieze” – zoöphor – is Greek for “that which conveys life.” Among the buildings’ defining lineaments and ornaments he names dentils (teeth), caulicoles (sprouts), echinus (sea-urchins), ovolo moldings (eggs), capitals (heads), auricles (ears), and astragals (ankle bones). He compares column bases and pedestals to feet, and a column’s entasis to pregnancy; building elements swell and protrude like flesh. Following Vitruvius, Poliphilo identifies sexual connotations that the columns carry in the details of the classical orders, but also notices “bisexual” rudentured shafts and unknown hermaphroditic orders mixing Doric (male) and Ionic (female) elements. He recollects the ancient atlantes and caryatids: structural columns taking human form, fluting mimicking women’s clothing, and responds to this animate, sexualized architecture with feelings of burning desire.

Ideas in the abstract risk sterility. To propagate desire, and fulfill our highest form of activity, creation, imagination requires the body’s sensuality and drives. Foreshadowing the depths of the matrix as flesh, Poliphilo conveys the incarnation of stone at the Great Portal through which he entered:

The craftsman had painstakingly set off this historia against a colored background of coralite stone introduced between the undulating moldings of the altar in the spaces surrounding the figures. Its incarnate coloration diffused itself throughout the translucent stone, imparting to the nude bodies and their limbs the semblance of blushing flesh.2

By extension, this intimates that the life force is latent in all of the architecture. Once inside, Poliphilo finds himself in a grotto whose mother-of-pearl revetment suggests his incorporation, enfolded in an architectural oyster-shell.3 An intimate form of encounter ensues in the pyramid’s foundations below where navigating a subterranean labyrinth by feel alone, he runs across a shrine to Venus glowing in the inchoate darkness.4 The body, in its turn, needs imagination to reciprocate love.

As he explores the debris-heaped terrain around a ruined ancient city, Poliphilo discovers a bronze colossus, lying on the ground, yet intact. This is an architectonic monument, a built form vast enough to inhabit. The colossus is a double, mirroring and merging the hero’s dreaming body with the architecture in his vision. In his recumbent, sleeping form, the gigantic statue is primarily bodily. Dreaming, he moans in pain, for ventilation holes bored into the soles of his feet suck in the breeze and make him resound like a musical instrument. Poliphilo clambers over his chest, spelunking his mouth, down his gullet, exploring the cavernous interior:

I saw intestines, nerves and bone, veins, muscles and flesh, as if I were in a penetrable human body. And wherever I was, each part that you would seen in every natural body had its name engraved in three idioms: Chaldaean, Greek and Latin, as well as what kind of diseases are generated in which, and their causes, remedies and cures.5

At the heart Poliphilo reads about Love, and suddenly feels his own unrequited love resurgent. As he breathes a heavy sigh, the entire bronze structure shudders in sympathetic resonance. The colossal figure is not solid, impervious metal, but enfleshed and responsive to his very spirit. Departing, Poliphilo sees a female counterpart, buried in rubble up to her neck. Like himself, the male statue suffers from existential separation, from love that is not able to exchange its life-giving energy and complete the erotic circuit.

Poliphilo’s dream-quest is to find and join his Polia. She is the female to his male, the mythos to his logos, the (lost) history to his (melancholic) modernity, the otherness hidden within him and around him. The neologism “hypn-eroto-machia” incorporates the philosopher Empedocles’ dual principles of cosmic change: universal Sympathy (the basis of natural magic, related to mimesis and the forces of attraction) and Antipathy (the force behind fragmentation and dissolution): Eros and Machia, Love and Strife. Poliphilo’s dream materializes these through divine figures, the former by Venus–Aphrodite, and the latter by Minerva–Athena in her martial aspect. Polia towers over Poliphilo’s narrative like a marble Venus crowned with the head of Minerva, an “Idea” as he calls her, willful and irrational, elusive and sensuous, strange and familiar. She is a matrix overflowing with Nature’s unlimited plenitude: a theocracy simultaneously generous and cruel, a paradox brimming with poetic ambiguity, resistant to analytic thought with its rational, divisive categories. The ancient city is a woman whom you love at your peril. To know her at an intellectual distance – a visual distance – can never satisfy him; he hungers for an unmediated, corporeal, tactile encounter. And the architecture he describes thus evidences his yearning to enter her – to become one with her – an intertwining of the self and the world.

A quattrocento commonplace characterized an unresponsive lady as being made of stone. In a sonnet, Lorenzo de’ Medici calls his mistress “adamantine,” hard as diamond.6 Polia too, not reciprocating Poliphilo’s love, is “frozen and stony.” To be a body of flesh is to return love, to recirculate the vital energy that links and bonds the world together. Only the embodied imagination, with its capacity for desire, can do so, and thus can participate in world making. To be flesh and thus receptive radiates and circulates erotic energy, not just between lovers, but throughout the universe into which the superabundant creative force overflows.

In every tale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses love transforms. Yet the metamorphoses in the Hypnerotomachia illustrate two kinds of subject–object intercorporeality: one constituted through mutual visibility (Athena–Minerva); and the other through touch (Venus–Aphrodite). With sensitive caresses Pygmalion coaxes hard materials to warm into flesh and by eye contact Medusa petrifies pliant flesh into rock. Both emerge between the lines in enigmatic images to unfold this cosmic process through poetic metaphor.

Poliphilo himself plays Pygmalion, a sculptor, and priest of Aphrodite. In the days when the love goddess had punished hard-hearted women by turning them to stone, Pygmalion builds his own woman, a statue of ivory. She is so beautiful he falls in love with her and asks Aphrodite to intervene. As he adorns the statue, strokes her, kisses her, he feels the hard ivory soften like beeswax under his fingers, sees her blush, and hears her begin to breathe. She comes to life as flesh and blood, an organic creature who in time will bear his child.7 Similarly, Poliphilo’s dream traces his invention of Polia from architectural “Idea” to a living woman with her own voice and story. She, ultimately, will make Poliphilo visible to himself.

Polia instantiates the other process as a type of Athena Polias, virgin goddess of wisdom and the city, who wears Medusa’s head on her breastplate. Beautiful Medusa makes love with Poseidon in Athena’s temple, and the angry goddess turns her hair to living serpents, cursing her that her eye contact will convert living flesh to stone. To avoid her eyes, Perseus deploys his mirrored shield, and decapitates the pregnant Medusa. Her monstrous offspring are Pegasus and Chrysaor, a golden giant, and in the ruined city Poliphilo encounters them as monuments: the winged horse and the bronze colossus. Perseus mounted on Pegasus, holding Medusa’s severed head, flew past Atlas holding the sky aloft, and transformed him into a mountain. At the city gate, the vast Titan materializes as a massive pyramid of white marble reaching to the heavens, entered through the howling mouth of a marble Medusa’s head, her giant snaky tresses serving Poliphilo as stairs.

Though flesh and stone are both stuff of the world and share materialized form, life and the non-living are differentiated by self-aware compassion, the bonding spark of desire linking subject and object. The paradoxical exclusiveness of the world and a body that share properties and qualities engenders the libidinal will to action, the intention to engage. Things of extreme beauty come to life, and monstrous things contaminate their surroundings, by a conversion of the erotic force. This motive force, however, is a mode of relationship, one possible only through the embodied imagination, and as such the ground of meaning. As Pérez-Gómez explains in Built upon Love,

architectural meaning is neither intellectual nor aesthetic in a formal sense, but originates instead in our embodiment and its erotic impulse. … The harmony of architecture is always tactile and “mater-ial” (referring to the mother of all). Architectural meaning, like erotic knowledge, is a primary experience of the human body and yet takes place in the world, in that pre-reflective ground of existence where reality is first “given.”8

His work suggests how to understand the Hypnerotomachia’s porous distinction of flesh from stone, their reciprocal convertibility, in terms of the tenuous and fragile qualities characteristic of the living body that confront Poliphilo at the goal of his pilgrimage.

Pérez-Gómez begins with Daedalus, mythology’s first architect, whose daidala were works marked by the mutual adjustment of the components and the integrity of their fit. Some of these awe-inspiring statues were so well composed that they seemed alive, and had to be tied down. In the underlying concept of harmony, connected to proportion, he notes that essential to beauty (venustas) is “an arrangement of parts that seduces the … observer and creates a significant space of participation. It is important to notice that harmonia initially had nothing to do with mathematics; it was a quality of embodiment (perfect adjustment) with the ultimate aim of love.”9 Tracing the origins of harmony to the ideal of things cleaving together in mutual agreement, which we might visualize architecturally in the spatial relation of the tectonic connection or the elements composing a city, he finds harmony later develops into a concordance of distinct elements or sounds, which form an orderly, internally consistent, and unified whole. He notes that for Galen, writing on anatomical structure in the second century, harmonia described “the union of two bones by mere apposition: a perfectly adjusted joint.”10 For the physician, the perfect relationship of heterogeneous and symmetrical parts to the whole were evidence of the divine hand, while today we can observe the centrality of embodiment persisting in our word “organization” which indicates the highest and most complex degree of order in a unified structure of specialized elements. While the linking power of Eros brings lovely things to life, this love is evoked, made, inspired by the beauty itself, and ultimately too, the origin and meaning of beauty are in the erotic cleavage of organic jointing. That which has been perfectly made, and thus made with love, verges toward animation. The craftsman seeking in the material its own potentiality, its pre-existing propensity to come alive when sensed, works to embody phantasia and passion from within it as Nature does in her own processes. The hand of the architect brings “Eros-qualities” to the raw materials, transubstantiating them from separate to composite, bestowing visibility and luminosity, ordering them through geometry, symmetry, proportion, refining through calibration, and elaborating through meticulous detailing, provoking the desirous onlooker to respond.

The background presence of Aphrodite and Athena, the goddesses respectively presiding over the tendency towards flesh and the tendency towards stone, introduces simultaneous desires to collapse the gap between subject and object through the act of touching, and through the eyes, the distance needed to see, to maintain the tension between subject and object. Beauty is integral to the mechanism that circulates erotic energy between lover and beloved, self and other, body and world, inhabitant and architecture. Yet becoming visible is not just “aphrodisiac”; it also depends on the Athena principle: the necessity to maintain the distance of know-how or embodied wisdom, only possible in a tense balance of proximity and separation, a “formula” for the architect’s ability with which we could also describe lived space, Plato’s chora, or the architectonic situation. Architecture as a form of embodied knowledge demands responsive touch. To perceive beauty, though, requires mutual visibility. To act and create in the world, we need the agency and responsibility of individual identity, our mortal experience of separateness, even the pain and terror of impermeable, existential solitude.

Sustaining the tension between pulling apart and joining, the architectural settings of the Hypnerotomachia reveal the co-presence of generationand corruption, form rising to visibility as cosmos, orderly knowable surface, and dissolving beneath the threshold of perception, its degeneration in time and through neglect and violence into formless prima materia. Poliphilo’s intimation of his own mortality and thus of his separate self, who appreciates beauty through vision and thinks as a maker, comes in the shape of architecture in a state of disintegration. At the abandoned city, the material corruption of the ruined buildings is spatially juxtaposed with a carved gigantomachy of lacerated, tormented and perishing bodies. The fractured elements render a fatal sensibility of transience, death and injury. A fallen column has lost its capital; minerals tarnish and bloom; masonry fallen out of place is cracked open and rank with weeds. Further on, surrounding the life-affirming Temple of Venus, he finds a study of machia in the brute decomposition in the Polyandrion: a vast necropolis of shattered sarcophagi and funerary monuments to separated lovers.

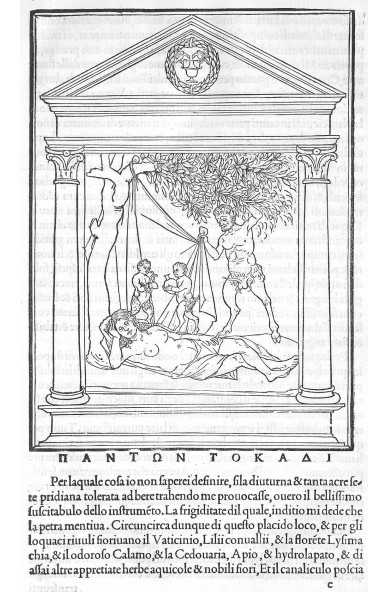

Figure 10.2 The Fountain of the Sleeping Nymph in the Garden of the Senses. Her breasts run with streams of hot and cold water

These opposing powers of Love and Strife, the dual font at which creation drinks, are centrally embodied in the human imagination, in a psychological faculty that Poliphilo encounters in architectonic form at the Palace of Free Will. There he traverses three drawing rooms representing his brain’s ventricles, cavities that staged the sensory processes of sensus communis, phantasia, and memoria. The frontal “common sense” reunites percepts from the five external senses into “virtual realities,” and archives these phantasms in the memory. But the phantasia (a word that keeps erotic connotations in fantasy) can anatomize holistic phantasmic images into elements that then can be reorganized into novel compositions, like a horse with wings, a woman with snakes for hair, a satyr whose features mingle goatish with human, or a building mixing Egyptian, Greek and Roman forms and technical arts.

The sequencing of architectural settings in the primary narrative hints at an identical process. Clustered or individual qualities (semblance, icon, material, figure, proportion, geometry, arrangement and so on) of each architectural object separate out, to be subsequently rejoined with others in new combinations, and increasingly high levels of visible order. Each work of architecture including the pyramid, the bathhouse, and the temple, geometrical complexes of stone and bodily figurations, gets dismembered behind the scenes into phantasmic elements that in successive re-compositions are transformed yet recognizable to the reader. Through the ruin settings, Poliphilo recognizes himself as incomplete, and anxiously desires intercorporeal reconnection with both Polia and the architecture itself. Thus his phantasia drives forward the iterative metamorphoses of his idealized physical environs, with his embodied imagination modeled on the perpetual self-creation of the cosmos.

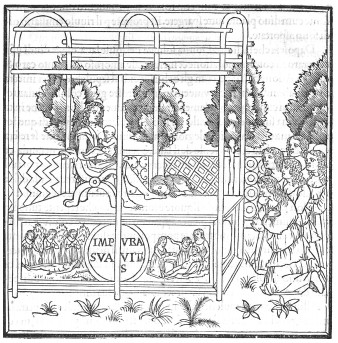

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Poliphilo’s dream of strife and love and the meaning of his dream lie in the necessary intertwining of the world in its most essential aspect with that which constitutes humanitas, a virtue governed by Venus. The culminating iconic image of Book I is a statue of Venus presiding over a garden on the Island of Cythera commemorating Adonis, her late younger lover:

On the tomb’s polished upper surface sat the divine mother sculpted as a woman recently delivered of a child, marvelously executed in priceless tricolored sardonyx marble. She was seated on an antique throne, which did not go beyond the vein of sard, while through incredible invention and artifice her whole Cytherean body had been carved from the milky vein of onyx. She was nearly nude, since only a veil formed from the red vein, left to conceal Nature’s secret, was covering part of one thigh. The rest of it cascaded to the floor, then wandered up just beside her left breast, turned aside, encircled her shoulders, and flowed back down towards the water, with astonishing craftsmanship closely following the lineaments of her sacred limbs. The statue manifested her motherly love by cradling Cupid who was nursing at her breast. Both of their cheeks were gracefully tinctured by the rosy vein, along with her right nipple. In this beautiful work, miraculous to contemplate! Nothing was lacking but the vital spirit!11

Figure 10.3 The Garden of Adonis: Polia and the other nymphs gathered around the statue of Venus nursing Cupid

The body and the other, who is also the world, are paradoxically at the same time one and two. For this reason, the non-dual or mystical experience is quintessentially erotic. The statue of Venus compassionately nurturing her newborn child demonstrates how bodily union intertwines Eros with machia’s agonizing separateness and difference. At this monument, Poliphilo and the nymphs insert themselves in the circuit of erotomachia by kissing the statue’s graceful foot. Juxtaposing visibility and tactility in embodiment, its stratified material binds creamy onyx, the archetypal color of cool, classical marble, with sard the color of living blood, whose visible vein reveals and traces a vital continuum between mother and son, but also between the architecture proper, the statues, and the human figures. In The Visible and the Invisible, Maurice Merleau-Ponty characterized this proximate distance in contemporary terms saying “ … a sort of dehiscence opens my body in two, and because between my body looked at and my body looking, my body touched and my body touching, there is overlapping or encroachment, … we may say that the things pass into us, as well as we into the things.”12 The design of this garden, dedicated to evanescent beauty, recognizes embodiment as a moment in time to be seized or lost, with an urgent message to be more than a mirror to love. Listen to the world that speaks; grasp occasio by the forelock and act; create in the world, and recirculate the energy that bonds all things.

Notes

1 Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, anonymous (Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1499).

2 Ibid, (unpaginated) Chapter V. All translations by the author.

3 Ibid, Chapter VI.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid, Chapter IV.

6 Lorenzo de’ Medici Sonnet XV, in The Autobiography of Lorenzo de’ Medici the Magnificent: A Commentary on My Sonnets. Translated with an introduction by James Wyatt Cook, together with the text of Comento de’ Miei Sonetti, reprinted from the critical edition of Tiziano Zanato (Florence: Olschki, 1991). Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1995 (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 129): 132.

7 Ovid, The Metamorphoses, Book X, lines 243–297.

8 Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Built upon Love: Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 2006), 42.

9 Ibid., 35.

10 Ibid.

11 Hypnerotomachia, Chapter XXIV.

12 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible; Followed by Working Notes, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 123.