1.7

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Use of Movement

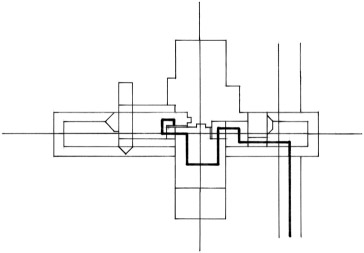

‘Ground plan and perspective view of Ward W. Willits’ villa, Highland Park, Ill’, Plate XXV in the Wasmuth portfolio of Wright’s work to 1910, must be one the twentieth century’s most compressed and beautiful renderings (Figure 1.7.1). Wright had developed the aesthetic of a central loggia flanked by twin masses and far-flying roofs in this well-known Prairie house of 1901. He had taken the quasi-sacred pinwheel hearth of his own Oak Park house (1896) and placed it centrally, to disturb and enrich a cross-shaped plan: a form of overpowering horizontality nailed by its chimney into the prairie. It offered a sense of place in contrast to the rush, noise and coal smoke of the Loop; apparent security in the face of contemporary social and technical change: Chicago ‘born in a flash . . .’ in the stark prairie.1

The classical gesture of welcome given by the Willits loggia is firmly rejected by a defensive balustrade, and you must slide along the eastern boundary to the protective shelter of the porte cochère. From your vehicle, you turn left and climb four steps to the front door, still under this great roof (Figure 1.7.2). You are welcomed, there is a seat before you, and you turn into the stair hall, which opens vertically above you. If it is not a personal visit, you enter the reception room to your right, overlooking where you started. Otherwise, you are invited to turn left and mount five broad steps, where progress is blocked by a slatted oak screen, the back of an unseen inglenook seat, but through it is glimpsed a 60-feet (18-metre) vista through dining room to porch and garden beyond. You enter a richly ambiguous space: still within the entry sequence, but unknowingly also in the corner of the living room. You are also in a subspace of its own. You turn left to face the street you have left and spiral around the room, before turning left at the hearth, where the sequence is repeated down the back of the second inglenook seat into the dining room. As you take a seat, you have completed ten turns.

In 10 intensive years up to leaving Chicago for Florence in 1910 to complete the drawings for the Wasmuth, Wright probably felt that he had extracted almost every possible variation from his Prairie idiom. In a remarkable series of houses, he had explored every imaginable permutation of plan arrangement, of ambiguously overlapping sequences of spaces, of setting up rooms with respect to hearth, sideboard or staircase, and of gradual movement from public to private territory. At their heart was always a binding and releasing, a grounding at the

Figure 1.7.1 Ward Willitts House, 1901, Highland Park, IL. Plans and perspective. The route processes through reception to the ‘conspicuous consumption’ (cf. Thorstein Veblen) of the dining room via the more informal living room

Source: Courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation (Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University). All rights reserved. All drawings in this section are reproduced from the original German book

Wright took a remarkable, intuitive leap in realising these projects. The formal properties, the tartan strips of the Froebel grid that the visitor traverses, have been extensively analysed by MacCormac (1968) and others, but they did not remark on the meandering or spiralling movement, which is widely thought to have originated in Wright’s exposure to Japanese culture.2 He did not visit Japan until 1905, but he experienced the Japanese Pavilion, the Ho-o-Den, at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Its symmetrical form suggested an axial entrance, like the Willits House, but this was denied by a rope across the axial steps. Visitors had to move one way, as they always do at world fairs.3 Before 1893, Wright was probably the foremost Western expert on the Japanese print: ikoye-i. By 1905, he had assimilated the seeming simplicity and sense of progressive discovery found in the Japanese building tradition.

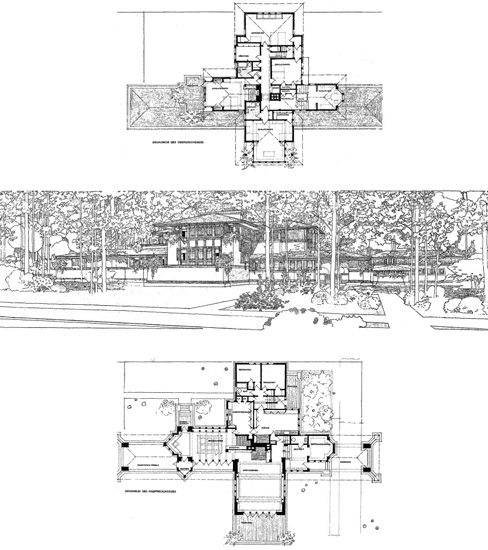

Wright learned from both tea-house and temple complex. Both have an indirect and shifting approach. In the first, small changes of direction are carefully orchestrated to direct attention to a tree, rock or garden feature; they are indicated by the paving or arrangement of stones and measured to the kimono-encumbered step and wooden clog (see Chapter 3.4, p. 178). It is a sequential process of renunciation, of withdrawal from daily cares, and at small scale. In the second, these changes of direction operate at the scale of landscape, making connections with the world beyond as part of a narrative. A stroll-garden, as at Katsura, is a literal representation of the inner sea, lost memory. Nitschke (1966) has shown how movement over an entire complex is worked into the form of a site, reserving its finest features for places of repose or surprise.4 Kyu-misu-Dera, in the south-eastern hills of Kyoto, is typical (Figures 1.7.3 and 1.7.4). Arrival at a great outer portal leads up the contours and past a glowing-red pagoda. Further up, you may purchase offerings or deposit prayers, before reaching a water basin filled by a cosmic dragon, symbolising and offering cleansing. You continue to find yourself high on a cliff, as if on a stage: to the left is the great Buddha Hall, to the right a view across the mountain towards the distant city. Your feet echo on wood, for a mighty timber platform intercedes between earth and sky. Beyond are three small temples and forest. Below, in a defile, at the foot of a great flight of steps, is a fountain, the purest water in Japan. The temple is dedicated to safety in motherhood; the woods above are wilder, animist: a place of spirits. You descend, drink or collect your water, and traverse the contours to leave by the gate where you arrived.

Figure 1.7.4 Kyu-misu-dera Temple, plan. Building dispositions are intimately linked to the site, developed organically from walking it. Key: 1 portal; 2 pagoda; 3 Buddha Hall; 4 Shinto shrines; 5 fountain

Source: Redrawn by John Sergeant

Japan 1917–22

Figure 1.7.5 Yamamura House, 1918–23, Ashiya, near Kobe, Japan. Exploded isometric

Source: Drawing by John Sergeant. Key: 1 entry; 2 living room; 3 Japanese-style rooms; 4 dining room

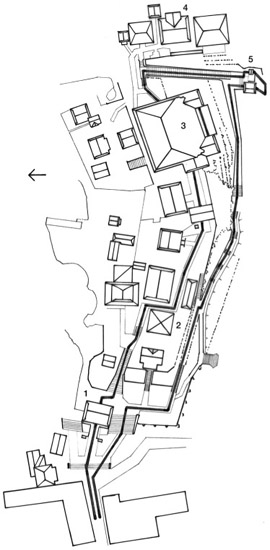

The commission for the Imperial Hotel provided Wright with an opportunity for more detailed study and to undertake smaller works, among them the Yamamura House of 1918–23, completed by Arata Endo (Figure 1.7.5). It has not been explored by Wright scholars, but I see it as a crucial link between the movement patterns of his Prairie houses and the subtle interplay with greater landscape of his later work. Sited in Ashiya, the building lies on the urban periphery, south east of Kobe. The Ashiyagawa River gushes down out of the hills, beautifully embanked in diagonally set stone, and the house crowns the ridge above. Wright ran the driveway along the contours up to the top of the ridge, which dominates the view of valley and sea. Poised there, with its service wing set higher, the house is angled to follow the lie of the land. Because of the slope, car arrival is restricted to a small rectangular forecourt, and the building takes the form of a series of single-storey set backs, like a stair up the ridge. The first element, the living room, spans the court, making a powerful threshold marked by four piers, through two of which the view can be glimpsed: opposite, a fountain drops water into a basin, and beside it, the door faces the mountain. The obvious, and grander, manoeuvre for the car to drop off passengers and then continue around the contours was impossible, as the land to the north west drops steeply; instead, it must execute a two-point turn and leave as it came. Garages are elsewhere. On entering, there is only a vestibule, and you ascend, to your left, the first of two stairs. This sets up a spiral that arrives in the reception room, a powerful space, anchored by its fire, aligned to the view, with built-in seats each side, poised above the land, which falls away on three sides. This would surely be enough, but Wright continues. You return to the stair and ascend one more level, stepping this time to the left, up the ridge, where you are confronted by a grand gallery, with views to the north west. It passes along the whole length of a three-room enfilade set three steps higher: Japanese-style rooms, linked by sliding doors and able to serve many functions, including sleeping. They lack paper screens, shoji, but have floor mats, tatami, to bestow a cultural authenticity. You become aware that the gallery is also a kind of internal verandah, engawa, signalling threshold to a Japanese person, a barrier between the boarded exterior and tatami-floored interior, traditionally never crossed without shoes being removed.5 Passing, perhaps hungrily, along the gallery, you ascend a second stair to the dining room, the goal of the promenade. The square table is offset under a pyramidal ceiling, and a loggia overlooks the entire length of the house and ridge beyond. Servants could produce a meal as if magically, for there has been no hint of the service wing hidden behind this highest level. Yet even this is not all, because the composition possesses an architectural coda: after eating, you stroll on to the stepped terraces of the roofs, feel the evening air and observe the sunset.6

Middle age: Los Angeles

By the time he returned to America from Japan in 1922, Wright had moved from a design procedure based on grids applied to a site to a more open acceptance of place. The pre-cast concrete ‘textile block’ he developed imposed a three-dimensional spatial ‘net’, which enabled him to negotiate with topography as found, and movement bound the two together. He had carried the mental ‘table’ on which he had learned Froebel’s Gifts to the flat prairies of the mid west career, but it was inadequate for the hilly sites of Los Angeles. The Storer House (1923) typifies these blockwork designs: it stands on a corner of a contour road in the Hollywood Hills. It follows Wright’s new grid cage of 16 × 16 inch (400 × 400 mm) textile blocks, extended beneath the ground plane to encounter and discipline topography, which produced an easy rocking motion up to the south-facing terrace. Until smog removed the view, ascending the house meant passing through this ‘textile-matrix’ to gain levels from which to gauge the horizon of distant Long Beach, beyond the great grid of the city.

The desert and Taliesin West

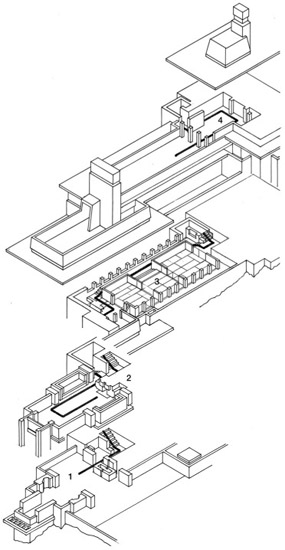

Pneumonia and Wisconsin winters drove Wright to the Arizona desert after 1930, and the vegetation and sense of space he found there clearly energised him. Falling Water, a dazzling series of Usonian houses, and Taliesin West followed in short order. His first desert camp, Ocatillo (1927), only survived a season, but was a clear response to new conditions. Wright enjoyed the achievement of a dust-pink boarded compound on a knoll, its 30–60º perimeter adjusted to the contours, canvas-roofed cabins ventilated by flaps, and a central camp fire: ‘my living room is as high as the stars’. He returned, to Maricopa Mesa, and built the second camp, Taliesin West (1938) as his winter home and headquarters for the Taliesin Fellowship, office and school (Figure 1.7.6). Although much altered, its primary design moves remain:

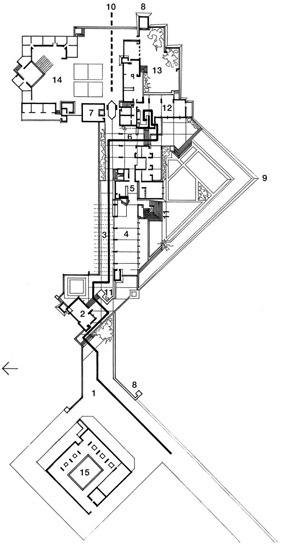

Figure 1.7.6 Taliesin West, 1938, Scottsdale, AZ. Wright brings the visitor to his door via a promenade that progressively takes you into the place, which was not ‘charged’ before its building. Key: 1 entry; 2 office and Wright’s study; 3 pergola; 4 drafting room; 5 kitchen and dining room 6 loggia; 7 kiva; 8 terminals; 9 prow; 10 borrowed landscape; 11 pictograph rocks; 12 garden room; 13 green garden; 14 apprentices court; 15 service area

Source: Drawing by John Sergeant

two alignments, one overlaid on the other at 45º.7 At my first visit in 1969, it seemed a long drive from Phoenix, and a wilder place, part of the choreographed journey by which Wright conjured up his most profoundly grounded project. It uses his ‘terminals,’8 a ‘prow’,9 borrowed landscape10 and the Anasazi prehistory of the place11 to achieve a deep specificity. The result is slow ascent and withdrawal from the urban grid, to-and-fro movement about the complex, release into a withheld vista and then compression through dark to light towards the ultimate goal, his hearth and garden. It has often been analysed, but the most persuasive account of arrival is that of Philip Johnson; whatever we may think of Johnson’s own architecture, it is valuable for being thoughtful, observant and made during Wright’s lifetime.

(Wright) has developed one thing which I defy any of us to equal: the arrangements of the secrets of space. I call it the hieratic aspects of architecture. The processional aspects. I would like to tell you about it briefly. You drive up from Phoenix, about 20 miles out, up a dusty desert road, wondering why you came because it’s terribly hot, and you go up a slight rise. Finally you turn into a particularly dusty, nasty and ill-kept road. But there is a little sign that says ‘Frank Lloyd Wright’.

You come to an agglomeration of tents and stones where the car stops. There is a low wall and you realise after you have been there and come back again, that he has been pushing out the spot where the car stops, further and further from his place. I’d like to recommend that to you and to me. The car, of course, is one of the deaths of architecture. It’s out of scale, it makes noise, it doesn’t please the eye. And you cannot, from a sitting position, even look at architecture. It has to be by the actual muscles of your feet.

He now makes you walk about 150 feet, until you get closer to this meaningless group of buildings. You’ve seen the plans many times and I’m sure you didn’t understand them any more than I did before I’d been there. As you approach, he starts you off on a slight slope, with the mountains to your left, and so up the first steps you go, away from the buildings instead of toward them. And how he takes your eyes and makes you follow. You go down the steps this way but the buildings are over there.

Then the steps turn at right angles and you go between two low walls, very much narrower this time. You have the sensation that you are always changing your point of view on the buildings. You turn, pass his office, you climb four more steps and pass a great stone that he has put there with Indian hieroglyphics on it, which he found on his place. There is no door in sight. There is a tent roof on a stone base but no door; there is nothing in sight. You just begin to wonder.

The path takes you down a long walk, about 200 feet perhaps, with this tent room on your right, the mountains on your left. You begin to wonder what is happening when, at your right, you pass the tent room, the building above goes overhead. But the view – two enormous piers – and you look again (a trick) through a dark room, a 6-foot room, out onto the terrace of Taliesin West: an enormous prow that sticks out over the mountains.

Now you’ve been climbing all this time and you never knew it because you never looked back; but for the first time, you realize you have been climbing and for 90 miles you look across the desert through that darkened hole. And again, of course, the steps start rippling. You go down three steps more and you are pulled out onto this prow of the desert. He calls it his ‘ship of the desert’. That’s where Frank Lloyd Wright is usually standing to greet you with his purple hair, his cape, and you say, ‘Now I’ve arrived at this magic place’.

But you’ve just begun your trip. He then leads you through a gold-leaf concrete tunnel that turns three times and you are pushed out into the single most exciting room that we have in this country. It is indescribable except to say that the light, since it all comes from the tent above, has infiltered and mellowed. You are just beginning to absorb this room when he opens a few of the tent flaps and this is when it really hits you. You look out – but not onto the desert. You look out this time on a little private secret garden that he has built beyond this room, where water is playing unlike any water in the desert. The plants are 20 feet high in this garden, and there is a lawn such as you have seen only in New England.

You say, ‘Now I see what I’ve come to Taliesin for’; you have not. He makes one more turn, two more turns. This time the door is 18 inches wide and you have to go in sidewise. It is entirely an inside room, no desert or garden. One wall is of plants. To be sure, you cannot see them: that is, you can’t see through them, but that gives you the jungle light that comes into the room. There is a shaft of light that comes from 12 or 14 feet above (this is a very high room now). The room is 21 by 14 feet, all stone. One entire length of it is fireplace; on the other long wall is a table and two chairs – and that is where you have come to be. You sit down with Frank Lloyd Wright and he says, ‘Welcome to Taliesin West’.

My friends. That is the essence of architecture.12

Movement in a literal sense was a fundamental part of a lifetime that spanned from the pace of a horse to the flight of a plane. Lloyd, Wright’s son, wrote of Kano, Wright’s black saddle horse, and admitted that, ‘Dad kept busy paying fines’ for speeding his customised yellow Stoddart Dayton roadster around Oak Park. Allen Brooks has described how the workforce on the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo arrived at 6.30 a.m. to find neat instructions fixed to all the cabinet work: Wright had travelled by night train from Chicago for his site visit and had arrived in the early hours.13 Ocean liners seem not to have exerted the fascination that they did for Le Corbusier, although Wright recrossed the Pacific from Long Beach to Yokohama and crossed the Atlantic to Rio in 1930, Florence in 1909 and London in 1939. The Taliesin Fellowship made annual migrations between its Arizona winter home and summer in Wisconsin: Wright in his Auburn Cords and later Lincolns, with a retinue of cars and a portable kitchen. His ‘aerotors’ would have taken off vertically to engage with an invisible, three-dimensional grid above the 1-mile matrix of Broadacre City. Movement had the same romance for him as for the rest of his generation; however, I would argue that the slower pace of season and time meant more to him. His autobiography speaks of the smell of Taliesin, wood smoke, pine boughs, wild plum blossom and huge bunches of flowers. He loved the effect of wear on materials, ‘wood best looks after itself’, the oil of the human hand, discoloration from weather, the icicles hanging from the eaves. His ‘In the nature of materials’ articles14 articulate the beauty of patina in metal, the verdigris of copper. There was no attempt to defy ageing, other than through the skill of the architect, by understanding and detailing. Architecture was to be there in the world, but in no way separated from the processes of time.

Notes

1 During Wright’s early career, Chicago went through deep social unrest. See Lionel March (1970) Imperial city of the boundless West: The impact of Chicago on Frank Lloyd Wright, The Listener, vol. 83, no. 2144.

2 Richard MacCormac (1968) The anatomy of Wright’s aesthetic, The Architectural Review, vol. 143, no. 852, pp. 143–6. Nute 1993. Visitors had to zigzag along the heavy roof overhang, peering into, but not entering, the spaces inside. This, and Wright’s substitution of the hearth for the tokonoma, or sacred recess, are documented here.

3 Pilgrims do the same, whether in the 300 BC Buddhist cave temples at Ellora, India, the symbolic revisitation of Jerusalem’s holy places (see Krautheimer 1983) or any number of European cathedrals and abbeys, along aisles around the apse containing the sacred relic, or indeed the haj. Pilgrimage, a physical embodiment of faith, is the primary form of processional movement in architecture.

4 Günter Nitschke (1966) MA: The Japanese sense of place, Architectural Design, March, London.

5 What Wright called the ‘Shinto be-clean’ admonition also marked the threshold: a transition of level from dirty exterior to the fragrant, soft-woven tatami a step above, the surface for sitting or sleeping. Wright had only encountered the Ho-o-den Pavilion at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and was not to visit Japan until his Prairie style was established. It was probably ignorance of this Oriental understanding of threshold that allowed him to enter directly from a covered exterior into the interior.

6 This entertainment, ‘walking the leads’, was an important ritual of seventeenth-century England, where the company would take the air after eating to consume sherbets and cordials on the roof.

7 For more detailed analyses, see: Neil Levine, ‘Wright’s diagonal planning’, in McCarter 2005; also John Sergeant, ‘Woof and warp’, ibid. See also Neil Levine, Frank Lloyd Wright and John Sergeant (1997) ‘MA’: Composition and reflex in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, Architectural Research Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4.

8 A square of red concrete is encountered at the start. It acts as a major terminal, key word in Wrightian composition, its counterpoint being the private pool, drawn in the second design, in the Master’s garden. It is inscribed with a poem by Walt Whitman.

9 A ‘prehistoric Native-American petroglyph boulder’ (found on the site), as Neil Levine has pointed out, is placed at the hinge of the great triangular prow that forges south from the living and working quarters and that, he argues, constitutes a new openness and flexibility in modernism. See his ‘Frank Lloyd Wright’s diagonal planning revisited’, in McCarter 2005.

10 The view of the Superstition Mountains, 30 miles away, was presented along the line of approach and beneath a bridge. This was lost when Olgivanna, Wright’s widow, enlarged her bedroom.

11 The second key to the turn south and view through the loggia is the massive stone box of the kiva. In practice, the Fellowship used it for meetings, akin to a monastic chapter house. Unlike the circular Pueblo or Anasazi kiva in the locality, for example at Chaco Canyon, the Taliesin version is square and above ground. However, Wright was clearly recalling it: the four lights set in the floor recall the four columns supporting the Indian original.

12 (1957) 100 Years, Frank Lloyd Wright and us, Pacific Architect and Builder, March, reprinted in Johnson 1979, pp. 193–8.

13 See H. Allen Brooks in Eaton 1969. Transcontinental trains were the means of transport until after the Second World War; not just a convenience, but also an inspiration. The Larkin Building, Buffalo (1904), pioneered air-handling to combat its location alongside a smoky marshalling yard.

14 ‘In the nature of materials’ was the title of Wright’s 1928 articles in Architectural Record and Henry Russell Hitchcock’s compilation of his work, Hitchcock 1942.