When the Englishman Richard Ford published A Handbook for Travellers in Spain (1845), he claimed that, ‘No Spaniard . . . ever took a regular walk on his own two feet – a walk for the sake of mere health’.1 In this, he not only pinpointed cultural differences between the two nations with respect to attitudes towards walking, but also the long-held British belief that walking was beneficial to physical and mental health. As early as the second half of the sixteenth century, there had been a renaissance in the acknowledgement of the health benefits of walking: following classical examples, it was thought to encourage the ability to think, as well as to encourage better physical health. This chapter investigates how a renewed interest in walking affected the design of landscapes, both private and public. Until the eighteenth century, the idea of a walk as a recreational activity in the countryside was somewhat of an enigma, and the main venue for such exercise was the garden. The reason was the condition of roads, dusty in summer and dirty in winter. To provide a firm surface for carriage wheels, good roads were ‘metalled’ with crushed stone or gravel to form hard surfaces. But, whatever the efforts, road surfaces remained a problem, as described by Robert Phillips in his 1736–7 Dissertation on the topic:

Now between wet and dry (for Example, when a Day or two of Rain there succeeds a Week or a Fortnight of dry Weather) the Sun, by drying, makes hard dry Ridges between the Rutts before it can evaporate all the Water in the Rutts, which every Shower of Rain fills again, tho’ it cannot soften the hard Ridges; but then it softens the Bottoms of the Rutts, so that Carriages sink still deeper into them. When the Weather becomes warmer, and the Days longer, as the Rutts begin to grow dry, they grow so stiff and heavy that they make a great difference in the Draught, at least that of one Horse in five. The Wheels go so hard, that when the Rutts are at the deepest, it is so dangerous and difficult to go out of a Track, that Carriages can hardly pass by one another without overturning.2

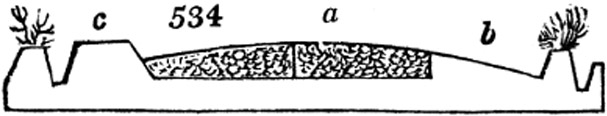

It is clear that this was a potent mixture, even without the horse and farm-animal excrement that was inevitably mixed in with it. Despite the fact that there was a tradition of leaving space for pedestrians along the sides of high roads, these were frequently soiled also (Figure 2.2.1). The state of the roads inhibited any pedestrian activity that was not necessary for transport or work related and, therefore, associated with the working classes (Figure 2.2.2). The activity of walking for the upper classes, therefore, took place where dry and smooth surfaces could be assured with gravel walks. Gravel originating from the Kensington and Blackheath areas became famous for the construction of London walks that were primarily found in gardens in the south of the country.

Figure 2.2.1 Standard road section

Source: J.C. Loudon, Encyclopaedia of Agriculture, 1835, London, p. 568

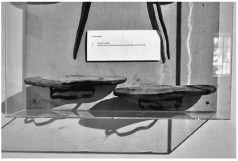

Figure 2.2.2 This patten was tied underneath shoes to prevent them becoming spoiled

Source: Sheffield Museum Services

Peripatetic walks

Some of the earliest surviving gardens of the mediaeval period were in monasteries, as cloisters surrounding courtyards, which, like ambulacrums in academic institutions, must have been intended for contemplation and philosophising. This kind of peripatetic walking – up and down, or round and round – was inspired by reports of Aristotle’s lyceum, where members met in the peripatoi, the covered walkway or colonnade. An ambulacrum was incorporated into the north side of the Hortus Botanicus in Leiden, which, though without doors, had glazed windows, to provide some comfort and protection from the elements. The openings provided direct access to the garden, so that, presumably with better weather, the walk could continue outside. Here, the pathways were shared with those approaching the plants in order to study them (Figure 2.2.3).

Figure 2.2.3 Cloisters surrounding courtyards, like those of the ambulacrums in academic institutions, were intended for contemplation and philosophising; examples at Colégio do Espírito Santo, Évora, built 1574–90

Source: Photograph by Jan Woudstra

Constitutional walks

By the time they were being rediscovered in the second half of the sixteenth century, English spa towns provided another reason for walking. Besides taking the water and the dietary requirements, there was a ritual for walking, sometimes at the beginning of the day or at the end. In 1626, evening walks at Knaresborough were taken ‘into the fields, or Castle-yard’, and provision was generally increased, special walks being created for the purpose. The new walk followed the River Nidd and included the famous Dropping Well, where, according to legend, Mother Shipton, an English prophetess, was born. Such destinations must have contributed substantially to the pleasure of walking.

Walking was considered conducive to health; in his essay ‘Of regiment of health’, Francis Bacon (1561–1626) emphasises the importance of exercise, which included walking in ‘Alleys, enough for foure to walke abreast’. Between 1597 and 1599, Bacon laid out Gray’s Inn Fields, London, for this purpose. It consisted of a series of parallel walks lined with elm trees, with one central, wide avenue and narrower ones to either side. These walks on the edge of the city, with good views northwards, became a popular destination, particularly after the ravages of the plague at various intervals during the seventeenth century, as good air could be appreciated there.3

The issue of walking was also addressed in the redesign of St James Park by Charles II after the Restoration in the 1660s, when he instituted so-called constitutional walks, probably intended as a pun on the Constitution, but meant for his constitution (and that of the Court) instead. The name Constitution Hill, the avenue between the present-day Buckingham Palace and Green Park, is a reminder of these daily walks.4 The Mall, laid out as a double avenue as part of these changes, also became and long remained a popular destination for promenading. The central avenue was dedicated to the game of pall mall, or paille maille, played with wooden hammers on long sticks. Promenading took place in the narrower avenues on either side of the track, which was fenced off with low boarding.

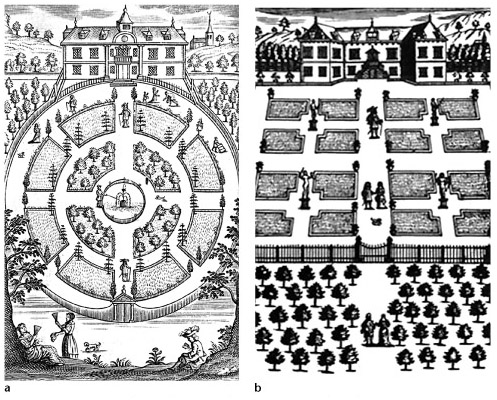

Figure 2.2.4 John Worlidge produced two theoretical models for gardens: the circular one (a) was designed so as to enable continuous walking, without the need to turn corners, but the disadvantage over the square garden (b) was that one was more likely to step into the borders

Source: John Worlidge, Systema horti-culturae, 1677, London

By this time, walking had become so much part of a healthy Puritan life that it was gener -ally incorporated. John Worlidge’s Systema horti-culturae (1677) included two hypothetical designs for walled gardens including walks as the predominant element. One scheme was a circular garden based on foreign models, where the walk that, ‘circundates that Garden is not unpleasant, for that you may walk as long as you please in it always forward without any short turning’. He believed nevertheless that, ‘The Square is the most perfect and pleasant form that you can lay your Garden into’, because this form of garden, with straight walks, was much easier to navigate as a pedestrian (see Figures 2.2.4a and 2.2.4b):

The delight you take in walking in it being much the more as you are less careful: for when you walk in a round or circle, you are more subject to trespass on the borders, without continual thoughts and observations of your Ground.5

Promenading

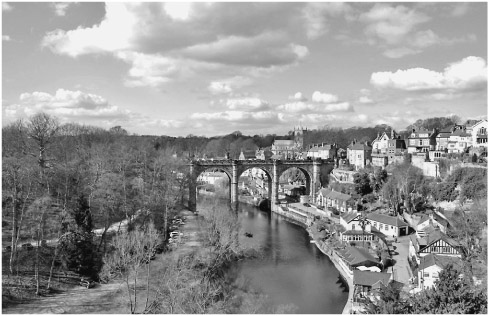

Although the initial intention of these latter walks may indeed have been for constitutional improvement, as they became fashionable they drew a new audience, more interested in social rather than health benefits. It was here that the tradition of promenading, defined as a ‘leisurely walk, esp. one taken in a public place so as to meet or be seen by others’6 began. The tremendous popularity of the initial walks soon encouraged further examples, designed for this combined purpose of health and social venue. These were the public walks designed for towns such as Liverpool, Bristol, Norwich, Nottingham, Shrewsbury, Lincoln, York, Knaresborough (Figure 2.2.5) and Scarborough, mostly along rivers and planted with avenues of trees. The enduring success of Pall Mall for promenading ultimately ensured its adaptation in the form of the shopping mall.

Bewilderment

Figure 2.2.5 One of the requirements in spa towns was the provision of public walks; there was an early example along the River Nidd in Knaresborough that incorporated Mother Shipton’s Cave and the Petrifying Well, which was first opened to the public in 1630

Source: Photograph by Jan Woudstra

As the grandest of gardens, conceived from the 1660s onwards, Versailles became a prototype for the baroque garden and was emulated everywhere. It was a landscape designed to impress, as an expression of the power of its owner, Louis XIV. The palace and gardens were conceived on a grand scale to belittle the visitor, who is thereby overwhelmed. The primarily geometric layout encourages the idea that it was conceived to be seen from above, but the full experience could only be had by moving through the landscape. This was normally done on foot, but the walks were wide enough to accommodate small chariots, or roulettes, also. In order to be able to show the gardens to his visitors, Louis XIV provided the programme for a route by which the gardens were to be shown, published as ‘La manière de montrer les jardins de Versailles’. Gardeners would be on hand to change the planting in the parterres even during a visit, to create a different perspective on the return, but mainly they served the turning on and off of fountains as the visit progressed, so that they could all be appreciated.7

One of the main features of the baroque garden was the bosquet, the woody part, referred to in English as the wilderness. Initially, such wildernesses were laid out in the maze-like patterns that also served for the layout of flower gardens; they progressed to simpler geometric patterns and ultimately were designed with winding walks throughout. The idea was an element of surprise. Whereas André Mollet had referred to going to the wilderness ‘for studious Retire -ment, or the enjoyment of Society with two or three Friends, a Bottle of Wine and a Collation’8, the main object in the cooler climate of England was to have a feature where one might be ‘bewildered’ through surprise walks. This could only be experienced by a moving walker.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the formal garden had given way to the landscape park of Capability Brown, but the idea of a garden as the main space for walking predominated, although it was renamed as pleasure ground when conceived in its ultimate form. The main purpose of a garden for walking is emphasised by Thomas Whately in his Observations on Modern Gardening (1770), which served as a guidebook for the new style. His section ‘Of a garden’ is wholly dedicated to the creation of walks. He noted that gravel walks contribute to the appearance of a garden, and he emphasised the need for the highest standards in their construction and maintenance, noting that, ‘a field surrounded by a gravel walk is to a degree bordered by a garden’, and that many ‘gardens are nothing more than such a walk round a field’. Various guidelines for the creation of walks were provided that were illustrated with a case study of Stowe, noting that:

The whole space is divided into a number of scenes, each distinguished with taste and fancy; and the changes are so frequent, so sudden, and complete, the transitions so artfully conducted, that the same ideas are never continued or repeated to satiety.

This referred to a number of themed walks, which in the case of Stowe were celebrated for the garden buildings and temples,9 which also shaped the iconographical programme of the gardens.10

The general design varied from place to place, affecting both rides and walks. At Blenheim, for example, there was a ride ‘round the park for occasional visitors’ of more than 3 miles around the perimeter of the park and ‘describing a wide circle round palace and gardens, which are casually and advantageously seen through glades in the progress, and exhibiting many magnificent pictures over the park and country round’. It was noted that:

[this ride] has ever been considered as the first of natural charms that Blenheim supplies, and as a coup d’oeil and compendium of all the rest; and as it may be taken in a carriage or on a horseback, it is neither accompanied with fatigue or delay. It may be taken in any weather.11

In contrast, the walks consisted of pebbly gravel, ‘of the most beautiful texture and regularity’, which was found to blend ‘utility with ornament’. These walks wound through ‘to the east between rising plantations, and clumps of trees and shrubs in various shapes, at intervals is opened to highly embellished lawn’. The main, or ‘Home-walk’, through the gardens was delightful and ‘sheltered by the winding of its direction from every blast’, and it possessed ‘sufficient variety in every part, with an aspect continually improving’. This walk ‘conducts to a Temple’ – in a ‘diverticle from the principal walk’, the visitor is ‘drawn aside to the contemplation of the Flower Garden’, which is included within a ‘thick grove’ – past the Palladian gate that forms the entrance to the kitchen garden, back on to the Home-walk and the Sheep-walk and past an open grove, at which point the visitor catches ‘a glimpse of the south front of the Palace, which is thrown into various perspective as we advance’ and various other views to features outside the park etc., providing the whole range of sensory experiences, visually open or closed, revealing views and interesting features and scents and sounds (see Figure 2.2.6).12

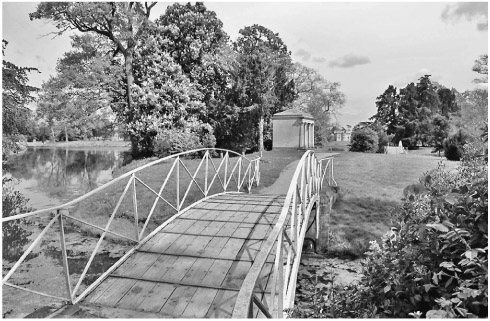

Figure 2.2.6 Walks in the eighteenth-century landscape park were normally incorporated within the pleasure grounds that contained a range of features; this example at Croome Court, designed by Capability Brown in the 1750s

Source: Photograph by Jan Woudstra

These experiences comply with those promoted by William Chambers in his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (1773) as originating from the Chinese, but which were, in fact, the canon that he would have liked to promote in the design of pleasure grounds. It also affected the directives for walks that express a range of visual and emotional experiences, to be summarised as follows:

- Walks are to lead ‘to all principal buildings, fine prospects, and other parts of the composition’ and in such a way ‘as it were by accident, and without turning back, or seeming to go out of the way, to every object deserving notice’.

- The distances between straight and winding walks are to be varied, with ‘closely planted thickets’ to hide and reveal views, to create ‘suspense with regard to the extent, as [well as] to excite those gloomy sensations which naturally steal upon the mind’, and more thinly planted areas. Here, the ‘ear is struck with the voices of those who are in the adjacent walks, and the eye amused with a confused sight of their persons, between the stems and foliage of the trees’. Various walks are unexpectedly turned into the same open spaces, so that, ‘the different companies are agreeably surprized to meet where they may view each other, and satisfy their curiosity without impediment’.

- Walks ‘en cul de sac’ are to be avoided in order to prevent ‘unpleasant disappointments’, but if they are necessary, they should always terminate ‘at some interesting object’.

- Walks are not to be designed ‘round the extremities of a piece of ground’, with the middle left ‘entirely open’, for though at first glance conceived as ‘striking and noble [so] the pleasure would be of short duration’. In smaller places, it might be appropriate to leave the larger part of the space open but taking care ‘to have a good depth of thicket, which frequently breaks considerably in upon the open space, and hides many parts of it from the spectator’s eye’. The projections of these thickets create variety, because they alter ‘the apparent figure of the open space from every point of view; and by constantly hiding parts of it, they create mystery which excites the traveller’s curiosity’. In places with a greater depth of thicket, recesses may be created for ‘buildings, seats, and other objects, as well as for bold windings of the principal walks, and for several smaller paths to branch off from the principal ones’. This disguises the idea of the boundary, ‘and affords amusement to the passenger in his course’, and, as it is impossible to ‘pursue all the turns of the different lateral paths, there is still something left to desire, and a field of imagination to work upon’.

- Crooked walks on flat, featureless land must either be ‘made by art, or be worn by the constant passage of travellers’. In general, unnatural windings must be avoided, and walks must only be turned for some apparent excuse, ‘either to avoid impediments, naturally existing, or raised by art, to improve the scenery’. Striking features for turning aside include a ‘mountain, a precipice, a deep valley, a marsh, a piece of rugged ground, a building, or some old venerable plant’. If ‘a river, the sea, a wide extended lake, or a terras commanding rich prospects, present themselves’, they may be followed ‘in all their windings’.13

- Walks ‘en cul de sac’ are to be avoided in order to prevent ‘unpleasant disappointments’, but if they are necessary, they should always terminate ‘at some interesting object’.

This reveals the intricacies and degree of detail with which walks within gardens were considered.

Public walks

Acknowledgement of the health benefits of walking and the lack of public facilities for it led, in 1833, to the appointment of the Select Committee on Public Walks that was ‘to consider the best means of securing Open Spaces in the Vicinity of populous Towns, as Public Walks and Places of Exercise calculated to promote the Health and Comfort of the Inhabitants’. The Select Committee found that, ‘the means of occasional exercise and recreation in the fresh air are every day lessened’ with the fast increasing population of towns, and that, despite the fact that some towns had public walks, ‘even at these places, however, advantageously situated in this respect, as compared with many others, the accommodation is inadequate to the wants of the increasing number of people’. As a consequence, the Committee reported in favour of the provision of public walks and open places, ultimately leading to the provision of public parks, which generally incorporated a much wider range of facilities than mere walking14 (Figure 2.2.7).

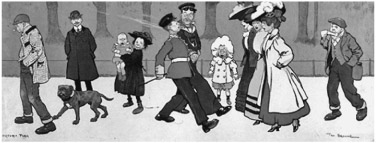

Figure 2.2.7 Tom Browne’s caricature of visitors to Victoria Park, London, emphasises the significance of walking and promenading as a purpose for the laying out of public parks

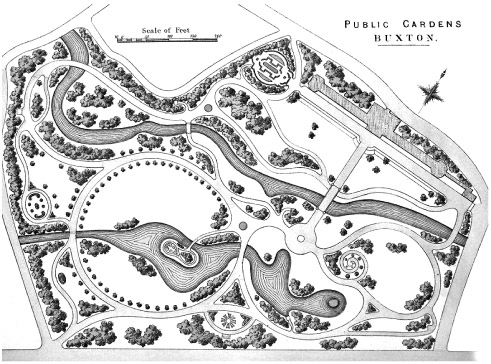

Figure 2.2.8 The layout of the Pavilion Gardens in Buxton Spa by Edward Milner, in 1871, emphasised not only the need for walking as a health requirement, but also walking for pleasure, in that the circuitous walks led to and from the bandstand, which was always near enough for the music to be heard

Source: H.E. Milner, The Art and Practice of Landscape Gardening, 1890, London

Not all ‘public’ parks were freely accessible, and a town such as Buxton Spa reveals the progress of public walk to public park. As in other spa towns, a public walk had been created here, designed by Jeffry Wyatville in 1818, especially for those taking the waters, in an area along the River Wye and then the Slopes opposite the Crescent, which was a topographically challenging site for the infirm, and so there was soon a requirement to embellish the walk along the river, which was executed by Joseph Paxton in about 1850. In 1871, the nearest section to the town was extended with the Pavilion Gardens, designed by Edward Milner. The latter was a public facility open for a charge, and was a good example of combining walks as a health requirement with pleasures. A conservatory to one side enabled an indoor walk during inclement weather, but it also contained a beautiful floral arrangement, tea-drinking facilities and, ultimately, an opera building designed by Frank Matcham, in 1903. Parallel was a broad outdoor terrace, elevated above the rest of the park. The garden itself had a centrally placed bandstand, with circular walks leading to and from it. These would have enabled circuitous walks that could be varied and were never too far from the music for it not to be heard. They would also have provided various choices and combinations of direction, the promenaders also presumably stepping to the music (Figure 2.2.8). The municipal parks laid out from this time on also provided many additional facilities beyond providing for walkers, typically including sports and leisure. Although the latter have long had predominance, because they have organisations to represent them, walking continues as the majority use of public parks today.15 With the current political, social and environmental issues, from obesity to climate change and with respect to the use of the car and home entertainment, the need to promote walking for health has never been greater.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank David Jacques and Peter Goodchild.

Notes

1 Ford 1845, I, i, p. 52.

2 Phillips 1637, p. 4.

3 David Jacques (1989) ‘The chief ornament’ of Gray’s Inn: The walks from Bacon to Brown, Garden History, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 41–65.

4 Weinreb and Hibbert 1983, p. 194.

5 Worlidge 1677, pp. 16–18.

6 The Oxford English Dictionary.

7 Christopher Thacker (1972) La manière de montrer les jardins de Versailles by Louis XIV and others, Garden History, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 49–69.

8 Mollet 1672, p. 13.

9 Whately 1770, pp. 206–27.

10 Clarke et al. 1997.

11 Mavor 1793, pp. 96–7.

12 Mavor 1793, pp. 59–85.

13 Chambers 1773, pp. 34–6.

14 Chadwick 1966, pp. 50–1.

15 Greenhalgh and Worpole 1995, p. 42.