Reflections on some recent projects by Herzog & de Meuron

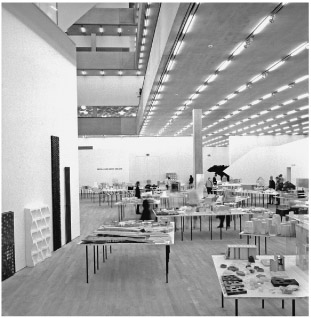

Model-making has been a central aspect in the work of the Swiss architectural practice Herzog & de Meuron since its beginnings, as illustrated by the prominence of physical models in several exhibitions of their oeuvre, for example the ones held in the Paris Centre Pompidou (1995), in the Milan Prada Foundation (2001), or in the Schaulager Museum in Basel (2004) (Figure 4.3.1).1 The reasons for their important use of architectural models are certainly multifaceted and complex, and, following a subjective reading, one could suggest a relation between this working tool and movement, namely, the way the architects imagine and foresee people approaching and accessing, moving into and through their buildings. In this sense, the numerous models built by the Swiss firm would illustrate, among other things, the architects’ concern with people moving around their buildings – admittedly a concern that should constitute a central aspect of each architectural project. However, this concern, together with the production of physical models, seems to be suffering a decline, in a time characterised by mainly virtual representation of architecture. This chapter aims to shed some light on Herzog & de Meuron’s exemplary use of physical models, while also constituting a plaidoyer for this working tool and its crucial role in the projection of movement.

The Parisian exhibition was conceived by the artist Rémy Zaugg in collaboration with the architects, as shown by a fax sent to the artist by Jacques Herzog on 25 November 1994.2 It contains an image of a Thanksgiving meal, illustrating a series of parallel tables, and the architect writes: ‘Dear Rémy, I have found an image of our exposition in the New York Times’.3 The exhibition conceived by the artist Zaugg manifests exactly this arrangement: a series of long, parallel tables, punctually interrupted by objects.4 Its final plan contains information about the different architectural projects shown, but also reveals that an important part of the exhibition consists of drawings and other two-dimensional documents, such as photographs or photomontages, with a limited number of three-dimensional models.5

After some exhibitions held at the Peter Blum Gallery in New York (1997) and the Tate Modern in London (2000), among others, the architects again exhibited a part of their oeuvre in the Milan Prada Foundation.6 This exhibition, held in spring 2001, shows the projects developed up to that point by both Herzog & de Meuron and OMA/Rem Koolhaas for the Italian fashion firm.7 The exhibition is again based on a series of parallel tables; however, the important presence of mock-ups, samples and especially working models is this time remarkable. Finally, in an exhibition organised in 2004 and held in the Schaulager Museum, the use of models becomes even more extensive, without saying that they conspicuously dominate the installation: the tables contain, almost exclusively, models representing different building volumes or envelope materials at multiple scales (Figure 4.3.1).8 For example, the table dedicated to the Prada store in Tokyo (2000–3) contains several cardboard, styrofoam and plexiglass models speculating on possible building outlines; others investigate building structure and envelope.9 The predominance of working models also becomes evident in the vade mecum published for this event.10 The booklet’s plan and the legend show that a large exhibit, entitled ‘Waste and sweet dreams’, consists primarily of building models, and the architects explain: ‘These models [. . .] were always crutches for a design process [. . .] That’s why we always said they were just waste products of a thought process’.11

Figure 4.3.1 Herzog & de Meuron: No. 250, An Exhibition, Schaulager Museum, Basel, Switzerland (2004). Tables exhibiting models, mock-ups and samples

Source: Photograph by Margherita Spiluttini

It becomes evident that, in their exhibitions, the architects show an important number of models as three-dimensional working documents, and two questions arise from this observation: first, can the exhibitions be understood as representing Herzog & de Meuron’s oeuvre in its architectural approach? Second, what is the reason for this keen interest in model-making? Concerning the first, Herzog confirmed, in a conversation with Zaugg: ‘For us, an architectural exhibition must be essentially based on a strong conception, at the same time precise and reflective, which presents and underlines the working method’.12 As the architect reports, an architectural exhibition should represent the working method applied, and, therefore, the abovementioned examples may be understood as representative, not only of their architectural approach, but also of their interest in models as tools and working documents. The reasons that lead to models taking on a central role in the architects’ oeuvre are, however, multifaceted and more complex. First of all, it is relevant to underline that Herzog & de Meuron understand the architectural models, not only as mere tools of representation, but also as an integral part of architecture or the built reality, as they explain:

In the end, the decisive factor for us is that every object we create – the drawings as well as the models – in terms of its own image or material structure is part of the resulting work of architecture, inasmuch as it allows the conceptual idea to be experienced rather than merely serve as an illustration.13

In this sense, models explain underlying concepts of the buildings they represent and, at the same time, they permit the experience of their physical, material presence. Yet, following an admittedly more subjective reading of their model-making, one can suggest a relation between the latter and the projection of movement: the numerous models produced by the office certainly help anticipate movement, by individuals, around and into the building. On this note, one should recall that physical models, by means of their three-dimensional nature, enable the perception of depth by architects, with their binocular vision. Furthermore, as objects, physical models also allow people to navigate around them, to take different points of view; in other words, they allow the architect to create a sequence of views, rather than one static view. Taking these characteristics of physical models into consideration, their important role in anticipating movement in and around a building becomes quite obvious.

A closer look at three, more or less recent, buildings by Herzog & de Meuron helps illustrate the central role of models in the understanding of their work, but also the relation here established between these models and the anticipation of movement. The library at Cottbus Technical University, a project represented at the Tate Modern and Schaulager exhibitions, was developed and built between 1994 and 2004.14 It is worth pointing out that the architects developed two projects for it: the first, a competition entry submitted in 1994, and the second version, from 1998, developed after obtaining the final commission. To explain the changes the project underwent in the meantime, Herzog & de Meuron produced a series of volumetric models, some of which they later assembled in a single image, showing a sequence of ten models, going from a rectangular block, to a cylinder, to a sinuously outlined volume.15 This evolution in the building’s outline certainly, and strongly, contributes to distin guishing the built object in its respective context: the curved outline of the library presents a powerful contrast with the surrounding rectangular Plattenbauten typical of the German Democratic Republic. However, the aspect of movement was also a crucial issue in the form-finding process, illustrated by the model series: the diverse outlines proposed would actually imply different movement patterns around, and ways of accessing, the building. Whereas the parallelepiped would likely have led to an orthogonal pattern and the cylinder to a circular one, the last four volumes proposed induce walking along various sinuous lines and they also permit a diversification of the entrance situations. In the final and built version, the latter are placed in ‘concave’ spaces, which seem to ‘embrace’ the visitor when entering the building. It is also in this sense that the architects describe, in a sketch published in their complete works and entitled, ‘The gestural language of the building’, the ‘embracing’ of the main access from the campus, but also ‘the “waist” entrances from two sides’ containing the ‘main access from the old city’.16 These notes, together with the red arrows marked in this sketch, confirm that movement around and access into the building were main concerns in this project and, moreover, were actually a form-defining aspect. However, if the sketch confirms the architects’ concern, the many volumetric models built for this project were also likely to have been a helpful ‘crutch’ in the design process.

Herzog & de Meuron describe the Prada store built in Tokyo as an ‘extremely visual, sculptural shape, but also a very simple and immediately recognizable one’.17 The building is located on a side street of a commercial area in the Japanese capital, an area characterised by buildings of rectangular outline. The Prada store distinguishes itself by its ‘crystal’ form, to quote the architects again, or by its irregular pentagonal plan, its continuous vertical section and its roof of differently inclined and outlined surfaces.18 Again, numerous models contributed crucially to the development of this project. They were present in the exhibitions held at the Prada Foundation and the Schaulager Museum, some experimenting with building volume, others concerned primarily with building material envelopes.19 Analysing this project and the models produced, one has to acknowledge the influence of the local zoning law, for, as the architects confirm, ‘the shape of the building is substantially influenced by the angle of incidence of the local profile’.20 If the zoning law restricts the building volume, the numerous models explore the important margin left open for experimentation. It is also in this sense that the architects describe the building volume as an ‘object, shaped by virtual zoning, made simpler, crisper’.21 Besides this local zoning law, the aspect of movement towards, and the access into, the building were the subject of long and intensive reflection, consideration and re-consideration, well documented in the publication Prada Aoyama Tokyo (2003).22 Through -out this design process, models served again as an important ‘crutch’: namely, a series of site models illustrate the architects’ considerations on this subject, as well as an important decision taken in this process. The architects decided to move the building out of the site’s central axis, towards the south corner, a move that permits the ‘luxury’ of an open area or a ‘plaza’ in downtown Tokyo, to quote the authors.23 Through this move, the architects created a more generous entry to the building, some ‘leeway’ in the dense neighbourhood of downtown Tokyo. Moreover, through this move, tested in the models mentioned, the architects influenced the way individuals move towards, around and into the building: upon visiting the Prada store, one first enters the plaza, possibly pausing on one of its benches, and then one walks across and into the building through the main entrance, placed on the lateral façade.

Figure 4.3.2 Herzog & de Meuron: VitraHaus, Vitra Campus, Weil am Rhein, Germany (2006–9). Working models illustrating a promenade through the building

Source: Photograph © 2013, Herzog & de Meuron Basel

If, for the Cottbus Library and the Prada Store, the relation established between the models and the anticipation of movement focused mainly on movement around, and access into, the building, the VitraHaus invites one to develop the argument further, or, more precisely, to the projection of the promenade inside the building, again by help of working models. The VitraHaus was developed and built between 2006 and 2009 for the furniture firm Vitra at their campus in Weil am Rhein, in the south-west part of Germany.24 It functions mainly as a showroom, and the basic element of the building recalls in its section the archetype of a house.25 By a process of ‘extrusion’ and ‘stacking’, these elements constitute a building of complex geometric disposition. Owing to this complexity, the anticipation of movement or the promenade through the building became a challenging task. Again, working models helped resolve the latter: arranged in a series of five, they illustrate first the access on the ground floor and then, subsequently, the stairs towards and the walk through the volumes of the first, second, third and fourth floors (Figure 4.3.2). For the development and verification of this promenade through the building, the model is an ineluctable tool, and this for different reasons: first, it would be difficult to represent the ‘stacking’ of volumes by a mere floor plan. Different colours or tones of grey could eventually explain this matter; however, a physical model is more efficient in the expression of depth through the binocular view of the architect. Further, the model also helps to illustrate the different points of connection between the volumes, and their verification from different points of view. In the case of the VitraHaus, these connection points are crucial, as they contain stairs and elevators and, in this sense, enable a continuous promenade through the building.

The question of the working model in the oeuvre of Herzog & de Meuron has elsewhere been further developed,26 and the examples illustrated here may only serve as a starting point for broader and more extensive reflections on models as tools to anticipate movement. With the observations shared, this chapter seeks to invite the youngest, ‘digital’ generation of architects not to underestimate but hopefully to re-evaluate the model as an admittedly basic, yet effective working tool.

Notes

1 Zaugg 1995; see also Celant 2003, 2008, Ursprung 2002.

2 Zaugg 1995, p. 104.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid., p. 105.

5 Mack 2000, p. 124.

6 Vischer 1997, Celant 2003, 2008.

7 Celant 2008.

8 See also El Croquis, 2006, vol. 25, no. 129/130, pp. 7, 8, 20, 21.

9 Ibid., pp. 210–11.

10 Herzog and Vischer 2004.

11 Ibid., n.p.

12 ‘Pour nous, une exposition d’architecture doit essentiellement reposer sur une forte conception de base, à la fois précise et réfléchie, qui présente et mette la démarche en évidence’, in ‘De la collaboration: un dialogue entre Herzog et de Meuron et Rémy Zaugg’, in Zaugg 1995, p. 24.

13 Quoted from Philip Ursprung, ‘Exposed experiments: Herzog & de Meuron’s models’, in Elser and Cachola Schmal 2012, p. 52.

14 Mack 2009, pp. 68–73.

15 Fernandez-Galiano 2007, p. 199.

16 Mack 2009, p. 70.

17 Herzog & de Meuron, ‘A house and a plaza’, in Celant 2003, p. 72.

18 Ibid., p. 70.

19 Ibid. and Ursprung 2002.

20 Herzog & de Meuron (2002) ‘Prada Tokyo’, Architecture and Urbanism, vol. 32, special issue, p. 14.

21 Herzog & de Meuron, ‘A house and a plaza’, in Celant 2003, p. 86.

22 Celant 2003.

23 Ibid., p. 63.

24 Concerning the architecture on the Vitra Campus, see Luis Fernández-Galiano, ‘Ernsthafte Spielerei’, in Fehlbaum 2008, pp. 54–62.

25 See: www.herzogdemeuron.com/index/projects/complete-works/276–300/294-vitrahaus.html (accessed on 16 June 2013).

26 Philip Ursprung, ‘Exposed experiments: Herzog & de Meuron’s models’, in Elser and Cachola Schmal 2012, pp. 51–6.