11

GENIUS AS EROS

Lian Chikako Chang

Opening

One’s first reaction to the book is entirely favorable. The type is beautiful and the book handles well. It is only as we turn over the pages that we become aware of something amiss… .1

C. E. Kellet

Charles Estienne’s 1545 anatomical treatise De dissectione partium corporis humani libri tres appears bizarre to contemporary eyes.2 Its woodcuts are anatomic both in a medical sense, in terms of depicting information about the body’s parts, and in a sense that has been interpreted as pornographic, in terms of displaying bodies and body parts in a manner intended to arouse sexual feelings.3 They have often been dismissed as failed scientific representations, particularly in contrast with the more anatomically precise and aesthetically refined images in Vesalius’ treatise. For historians of medicine Kenneth Roberts and John Tomlinson, the images are “mannered, even surrealistic,” and “quite unconnected with any didactic purpose.”4 For historian Bette Talvacchia, “the result can be hardly less than disturbing, fueled by motives that creep toward the sadistic.”5 More prosaic but just as damning, literary historian Arthur Tilley has described Estienne as an underachiever whose “learning was greater than his science.”6

The failure of these images, however, is only apparent when judged from the point of view of modern science. In light of Estienne’s sixteenth-century humanist context, a different interpretation becomes legible. Whereas modern anatomy focuses on body parts, often literally removed from their context, and modern pornography focuses a relentless gaze on parts and actions similarly divorced from human experience, the figures in De dissectione are emphatically immersed in a context that is at once religious, artistic, philosophical, and erotic. In this essay I will argue that this contextualization, disturbing as it may seem, allows us a glimpse of the erotic role of vision and transformation in Renaissance notions of creativity.

Charles Estienne was born in 1504 into the French Renaissance’s most prominent family of printers. His father Henri, brother Robert, and nephew (also named Henri) printed hundreds of translations and commentaries that set standards for French scholarship, typography, and orthography. Their works included influential texts on the Greek, Latin, and French languages; the authoritative New Testament; and the complete works of Plato. While studying classics in Padua in the 1530s Charles became interested in medicine and botany, and he subsequently studied Galenic medicine in Paris as a classmate of Vesalius.7 As a medical doctor Estienne lectured on anatomy in Paris, as a printer he published over a hundred works, and as a scholar he produced a varied oeuvre including texts on ancient and modern agriculture, clothing, and a road-guide to France.8 His two monumental projects were an influential eight-hundred page encyclopedia on the ancient and biblical world entitled Dictionarium historicum, geographicum, poeticum; and the enigmatic De dissectione, in Latin and later in French.9 Estienne became King Henry II’s printer in 1551 and under royal privilege edited and published the complete works of Cicero using the text established by his brother Robert.10 While Robert was exiled from Catholic France to Calvinist Geneva, Charles ran into financial difficulties and died in 1564, imprisoned for unpaid debts.11

In the absence of a patron, Estienne was author and publisher of De dissectione throughout its fifteen-year gestation. It was the most expensive work from the famed press of Estienne’s stepfather Simon de Colines, and its printing was nearly complete in 1539 when its publication was delayed by a lawsuit between Estienne and surgeon–illustrator Estienne de la Rivière.12 As such, although published in 1545, two years after Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica, Estienne is considered Vesalius’ contemporary or forerunner.

The cultural context surrounding anatomical practices in Estienne’s time can be roughly summarized through the following three points: First, as cultural historian Jonathan Sawday describes, the representational tradition of the doctrine of incarnation indicated God’s willingness to assume a human form in order to redeem mankind from its sins and corporeal bonds.13 Incarnation marked the human body as inhabited by a divine grace that could be witnessed and understood. Second, Renaissance man had a newfound faith and fear in his own mind and vision as quasi-divine means to penetrate, understand, and engender change in oneself and the world.14 This realization elevated sight and the image not only as conveyors of ideas, but as generative and potentially transformative points of contact with order and meaning. Third, the sixteenth-century print revolution, enabled by Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type in the previous century and advancements in woodcut techniques, allowed the creation of both the printed bible and the printed and fully illustrated anatomical treatise.

In turn, a more accessible printed bible fueled Protestant emphasis on each individual’s encounter with scripture, and particularly the Calvinists’ insistence on each person’s scrutiny of their inner state. According to Sawday, the Calvinist belief that to understand the human form was to understand God’s design brought theological and anatomical interests into alignment.15 Dissections were often performed on the bodies of executed criminals, which fulfilled the pragmatic need for corpses and aligned with the notion of the anatomy theater as a site for redeeming the criminal body – and, symbolically, fallen mankind – through the sight and knowledge of God’s work.16 It is also relevant that alongside the bible and anatomical treatise, there was a third newly emerging genre of printed material: the pornographic text and image, which historian Lynn Hunt describes as most often being used between 1500 and 1800 in the service of criticizing religious and political authorities.17

As an anatomist, scholar, publisher, brother, and uncle of prominent early Calvinists – and as a worldly courtier in contact with the circle of author Pietro Aretino, the Italian writer considered to be the founder of modern literary pornography – Estienne was working at a convergence of these currents in humanist culture.18

The three books of De dissectione

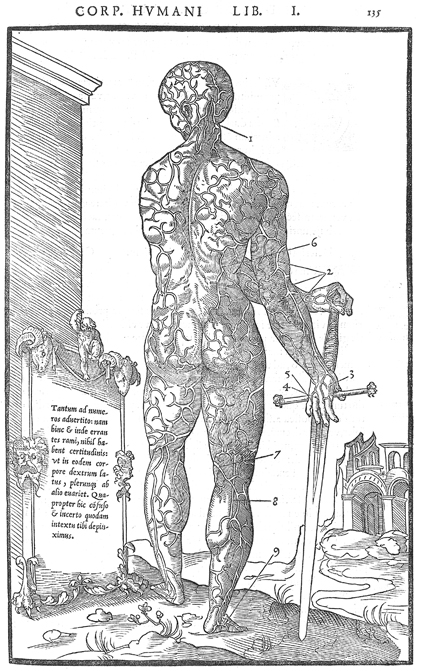

De dissectione, with sixty-two full-page woodcuts and just over four-hundred pages, comprises three books. Book One introduces anatomy not with dissection, but with a construction of the body, the noblest construction by the noblest of creators, constructed from the bones, cartilage, ligaments, nerves, muscle, veins, arteries, heart, liver, and fat, to the skin, fingernails, and hair. As throughout the treatise, and in accordance with the Renaissance belief in the anatomized body as an active participant in its own dissection and redemption, the figures are depicted alive (Figure 11.1). They are often set outside the city, next to a building or ruin, perhaps emphasizing the liminal state of these bodies – partially made or unmade, between life and death, at the margins of civilized society yet still engaged with it.

Figure 11.1 Book One showing veins and arteries. Estienne, De dissectione, 135

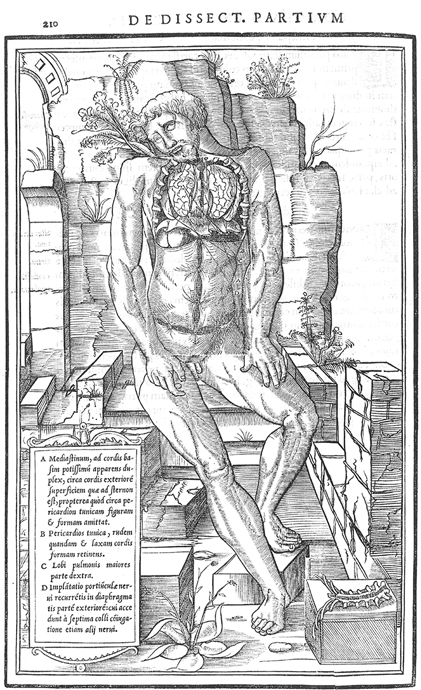

Once this body is made, it is unmade in Book Two, which shows inset views into the dissected body. Whereas today we would expect a catalog of body parts or a series of sections (or, more likely, a three-dimensional model generated from simulations or digitally controlled slices or scans), these woodcuts narrate the process of dissecting a single body. The series follows the order of anatomical dissection at the time, from lower abdomen to upper abdomen, throat and, finally, the head. In this way, Book Two serves as a companion to, or replacement for, a visceral encounter with a body in the anatomical theater (Figure 11.2). As the dissection progresses, the body becomes increasingly precarious, with the skin stitched to close previously opened areas and the body propped up by natural or architectural fragments whose state of ruin mirrors that of the body.

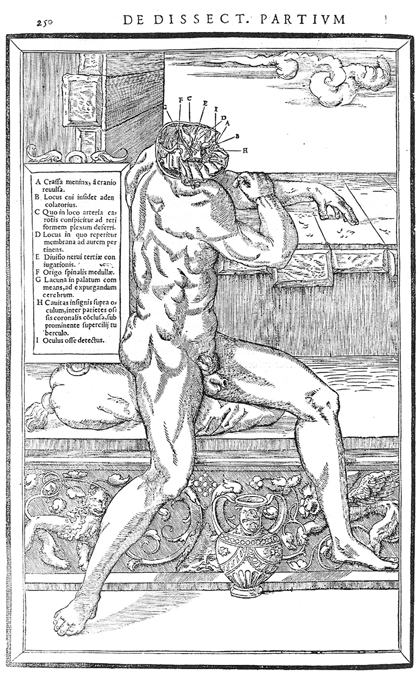

At a certain point, this body sheds its macerations and once again becomes graceful and nearly whole. Book Two turns its attention to the head, illustrated through eight figures in contrived yet elegant positions. The settings mirror this relative grace: fragments and ruins give way in part to more elaborate architectural settings that play on the ambiguity of interior and exterior. In three cases, windows frame a view to the sky, and bi-lobal and circular openings mimic the sectioned head, drawing an analogy between these two entities that offer communication between the inside and outside (Figure 11.3). The section cut through the head is always what we would call transverse – or, perhaps in Estienne’s context, a horizontal cut separating the lower from the upper, the bodily from the celestial.

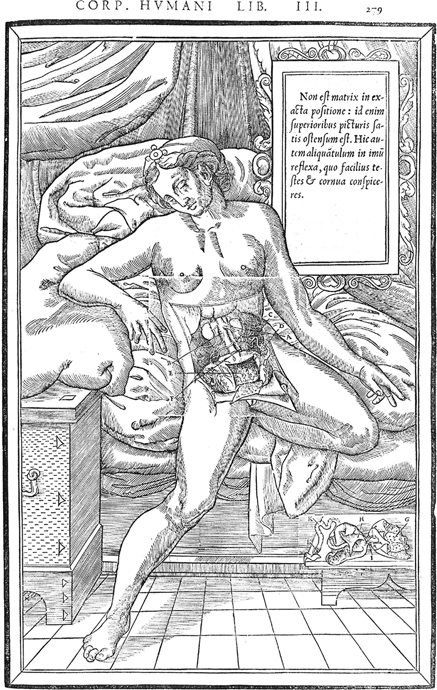

Book Three opens with ten woodcuts devoted to the female reproductive system, which gives us the treatise’s only images of women. The text discusses the womb and other female anatomy, as well as techniques for handling various situations during pregnancies and births. In the woodcuts, the women display themselves in luxurious architectural settings, usually interior and above all in bedrooms with plush drapery and beds. Their legs are spread and they lounge in graceful and inviting poses, seemingly consenting to their own dissection and participating in the display of their sexual organs and interiors (Figure 11.4). In one case, a figure lifts two placentas to reveal twin fetuses in her flayed womb.19 These sexualized images comprise the work’s final new full-page woodcuts, the climactic culmination of building and dissecting the human body. Beyond this point, the book continues with detailed discussion of a few chosen parts: the eye, muscles, and spine, removed from their context of body and world and illustrated by smaller images inset in the text. Finally, the book ends with recommendations for dissection methods, tools, and the anatomy theater.

Figure 11.2 Book Two showing the lungs. Estienne, De dissectione, 210

Figure 11.3 Book Two (after Caraglio’s Mars) showing structures surrounding the brain. Estienne, De dissectione, 250

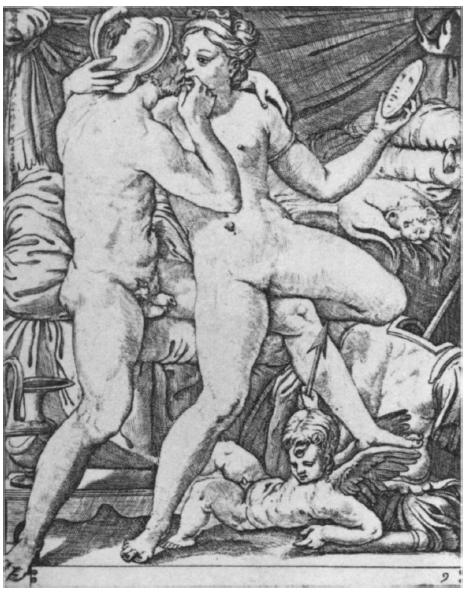

Figure 11.4 Book Three (after Caraglio’s Venus) showing the womb. Estienne, De dissectione, 210

Loves of the gods

Our eyes are drawn back to the young women at the opening of Book Three. Posed in suggestive positions, these women call attention to themselves in a manner unlike any others in the treatise. Talvacchia and medical historian Charles Kellett have traced nine of the ten female figures back to two drawings by Rosso Fiorentino and eighteen by Perino del Vaga for Caraglio’s Loves of the Gods, a series of engravings depicting pairs of Greek gods in erotic embraces (Figure 11.5).20 The women were not whisked directly out of Caraglio but underwent two transformations before the anatomical views were inset in their torsos. First, each goddess was redrawn without her male god, a process that required slight adjustments to her limbs. Second, the settings were changed from the mythical to the mortal realm, exchanging putties and divine allegorical symbols for more human, architectural surroundings.

Estienne’s choice of these women remains enigmatic. Loves of the Gods was popular in France and particularly in the humanist court of François I, an avid patron of Italian erotic art. As such, it seems that the figures were meant to be recognized. Talvacchia suggests that Estienne wanted to benefit from the “cover” of a mythological setting to legitimize otherwise unabashedly erotic images21 Kellett, in contrast, suggests that it was a question of convenience, possibly reusing figures drawn by Rosso for his own unfinished anatomy.22 Neither explanation is satisfying. First if the mythological setting legitimized the erotic, then the exchange of mythological and divine attributes and environment for earthly and mortal ones seems implausible. On the other hand, the overall cost and elaborateness of the treatise, and the procedures necessary to adapt the figures while retaining the original reference, seem too involved to make convenience a likely choice – particularly given the sophistication of Estienne’s humanist and courtly audience in reading visual quotes and subtle allegories. I propose another reading.

The love of mortals

Plato’s Symposium contains a whimsical fable told by Aristophanes on the origins of human difference and desire. As Sawday observes, this tale became a crucial text in the Renaissance exegesis of Christian and Neoplatonic sources, and Estienne would have been familiar with it through his family’s publications of Plato.23 In this story humans were originally spherical with two heads, four arms, four legs joined at the torso, and a terrible hubris. Zeus plotted their punishment:

“Methinks [said Zeus] I have a plan which will humble their pride and improve their manners; men shall continue to exist, but I will cut them in two” … and as he cut them one after another, he bade Apollo give the face and the half of the neck a turn in order that man might contemplate the section of himself: he would thus learn a lesson of humility.24

Figure 11.5 Jacopo Caraglio, Mars and Venus (after Perino del Vaga), Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, Rome, FC5934

Apollo was also bidden to heal their wounds and compose their forms. So he gave a turn to the face and pulled the skin from the sides all over that which in our language is called the belly … and took out most of the wrinkles … he left a few, however, in the region of the belly and navel, as a memorial of the primeval state … each of us when separated, having one side only, like a flat fish, is but the indenture of a man, and he is always looking for his other half.25

The belly, the container for the womb, was where the original spherical man was cut in half and where this wound was healed; Zeus’ dissection ends one life and engenders another. In his narrative of the transgression of life both through death in dissection and through fertility, Estienne mimics this primeval anatomy.

The goddesses of Loves of the Gods were banished from their divine height to earth and severed from their godly lovers. Estienne’s women, however, are shown not in the moment of their fall, but their ascent: arms and legs spread for an embrace which eluded them in life, they seek a vision of wisdom, a revelation of their primeval wholeness through the contemplation of their section. Once mortals have fallen, as Plato writes in Phaedrus, they forever desire to re-grow their wings through love, in order to ascend and glimpse a wisdom normally hidden from our mortal eyes.26 Peering into the body’s secrets through dissection promises such a glimpse, bringing anatomist, anatomized, and audience closer to God through a revelation of his work.

The womb has long been understood to emit a symbol of death in its menstrual blood while offering transcendence of death through its fertility. In sixteenth-century anatomy, which was understood as a process intended to ritually transcend mortal death, the womb was a particularly privileged site. The womb is what Vesalius exposes in the dissection on his frontispiece, under the masterful hand of the anatomist at the center of a swirling crowd of onlookers (Figure 11.6).27 Like Vesalius, I would suggest, Estienne centers his anatomy on the womb as the most apt site for this allegory of fall and ascent, decay and fertility.

What happened to the male gods once separated from their lovers? Caraglio’s Mars, the lover of Venus and possessor of a generative virility, appears as the penultimate male figure in the text. Twisting his body to offer the viewer a glimpse into his sectioned brain, his head is tipped enough that were his brain filled with fluid, it would spill. On the ground between his legs is a vase, positioned so that it might receive this flow from his brain – or more directly, from his suggestively spout-like penis poised above the vessel. The suggested passage between brain, penis, and vessel recalls the theory of generation that Leonardo da Vinci illustrated in his sketch of human copulation. Leonardo, who like Estienne was brought from Italy to the court of François I, depicts the fluid of male fertility passing from the brain, through the spinal cord, and out the male member. Likewise, a close-up of the sectioned head reveals that Estienne has chosen this figure to represent (Figure 11.3 at F) the connection between the head and the neck in the beginning of the spinal cord. This section also cuts (Figure 11.3 at I) through the eye.

Figure 11.6 Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. (Basel: Ex officina Joannis Oporini, 1543), frontispiece

Genius as Eros

The idea of male fertility originating in the head recalls Marsilio Ficino’s emphasis on the soul and vision, the sixteenth century’s newfound faith in mankind’s creative capacities, and as historian D. T. Starnes describes, the Renaissance concept of genius as developed through interpretations of Plato’s Timaeus and Apology.28 Ficino, translator of Plato and the most influential Christian Neoplatonist of the fifteenth century, had insisted that the human soul was divine, with immense creative powers. Creativity, however, depended on our ability to partake of divine order through vision, through which we can receive a glimpse of the universe’s original and divine order. Vision in the sixteenth century was as carnal as it was celestial; for Ficino, a lover’s desirous gaze could pierce and wound his beloved. According to architectural historians Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier, the Dominican philosopher Giordano Bruno, likewise, found an erotically tangible vision in the sight of the magus, who had to both seduce and fall in love with his subject in order for his magic to take effect.29 Charles Estienne, in his Dictionarium historicum et poeticum of 1553, ties the notion of genius and its creative (literally, generative) capacity to this kind of vision that is at once lustful and divine:

The ancients called Genius the god of nature, who had the power of generating all things; hence each thing was said to have its genius… . Some suppose Genius to be the soul or mind itself, or a god, or a spirit, which incites human beings to pleasure or lust. Therefore the ancients named those Geniales who were much concerned with external appearance and pleasure. Hence the proverb, to indulge one’s Genius.30

As Estienne’s description of the spinal cord’s central canal is considered to be his most important scientific contribution to anatomy, it is fitting that he should include an allegory endowing it with a significant role as the conduit of imagination and fertility.31 Brought together, I would suggest that the head and womb offer a potent image of fertility in the creative genius of lust and the sight of beauty.

In turn, the sixteenth-century reader’s appreciation of these eroticized drawings might recall another experience of Venus’ charms, implicating the reader in the visceral and carnal nature of anatomy while turning the treatise’s pages. That the dissected views into the women’s bodies comprise a mere two to five percent of their images’ printed areas should suggest that the explicit depiction of anatomical detail, as separate from its context, was not the priority.32 Rather, the dissected views are literally inserted into a rich, subtle, and much wider visual context. Because of their small size, even as the dissected women willingly invite the reader’s gaze, there are limits to what you can see. Perhaps the experience of peering into these images serves as a proxy for being in the anatomy theater, straining to catch a glimpse of what you are told is there. The reader’s experience also mimics the ultimate mystery of bodily knowledge. As Sawday observes about anatomical practices in general, “the ‘thing’ – the secret place, the core of bodily pleasure or knowledge of the body – always escapes representation.”33 This elusive character, I would suggest, is less pornographic than it is erotic, inviting and endlessly deferring our desirous gaze. In this sense, I would argue that these sexualized images were not in their context primarily degrading or, in Talvacchia’s terms, sadistic. Instead, they offered a means through which mortal men and women could strive towards an encounter with celestial order, by becoming inspired towards creativity and fertility.

What strikes us as surprising and unsettling in De dissectione is that Estienne places the human body not against a background of objectivity, but rather, embeds it through allegory and rhetoric within layers of meanings and intentions. Visually representing a cut and opened body was a relatively new process in Estienne’s time, and it was also not a neutral one. De dissectione is at once erudite, with a deep knowledge of Galenic medicine and historical references; scientific, with “numerous excellent and original observations contained in the text”; erotic, with its opened and suggestively posed women and men; and philosophical and religious, with its cosmological and ethical implications. Vesalius’ much more famous work, in comparison, has been shown to be just as laden with symbolism, but his more polished visuals allow us to gloss over his carnal and theological content while admiring his prescient modernity.34 Estienne’s treatise has images that are not fully formed, contradictory, and less beautiful to our eyes – and they give us pause.

Notes

1 C. E. Kellett, “Two Anatomies,” Medical History 8 (1964): 343.

2 Charles Estienne, De dissectione partium corporis humani libri tres (Paris: Apud S. Colinaeum, 1545).

3 Although modern use of the word “pornography” is a nineteenth century phenomenon, according to Lynn Hunt, the modern pornographic tradition begins in sixteenth century Italy and 17th century France and England. Lynn Hunt, “Introduction,” in The Invention of Pornography: Obscenity and the Origins of Modernity, 1500-1800, ed. Lynn Hunt (New York: Zone Books, 1996), 10, 13–14. Sawday describes the images of women in De dissectione as “posed in an extravagantly sexualized manner.” Jonathan Sawday, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture (New York: Routledge, 1995), 194.

4 K.B. Roberts and J.D.W. Tomlinson, The Fabric of the Body: European Traditions of Anatomical Illustration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 171–2.

5 Bette Talvacchia, Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 187.

6 Arthur Tilley, “Humanism Under Francis I,” The English Historical Review 15, no. 59 (July 1900): 456–78.

7 As Roberts and Tomlinson describe, Estienne was awarded his medical doctorate in 1542. Roberts and Tomlinson, Fabric of the Body, 168.

8 Charles Estienne, Praedium Rusticum (Paris: Apud Carolum Stephanum, 1554); Lazare de Baïf and Charles Estienne, De re vestiaria libellus (Lyon: Gaspar & Melchior Trechsel, 1536); and Charles Estienne, La guide des chemins de France, reueue & augmentee pour la troisiesme fois. Les fleuues du royaume de France, aussi augmentez (Paris: Charles Estienne, Imprimeur du Roy, 1553).

9 Charles Estienne, Dictionarium historicum, geographicum, poeticum (Paris: Apud Carolum Stephanum, 1553); and Charles Estienne, La dissection des parties du corps humain (Paris: Apud S. Colinaeum, 1546).

10 Marcus Tullius Cicero, Opera Omnia (Paris: Charles Estienne, 1555).

11 For Estienne’s biography, see Jules Balteau, Marius Barroux and Michel Prévost, “Estienne,” in Dictionnaire de Biographie Française (Paris: Letouze et Ané, 1933), 95; and Fred Schrieber, The Hanes Collection of Estienne Publications: From Book Collecting to Scholarly Resource (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 1–8.

12 On the expense of De dissectione, see Kellett, “Two Anatomies,” 343. On the lawsuit, see George P. Burris, “The Illustrations in the De Dissectione Partium Corporis Humani Libri Tres (1545) of Charles Estienne (1504-1564),” Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 46 (1966): 151.

13 Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 106.

14 Katharine Park discusses belief in the power of vision in the context of sixteenth-century holy anatomy. Katharine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2006), 52, 255.

15 Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 106.

16 Sawday discusses how this symbolism helped to overcome the taboo of opening and looking inside the body. Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 84.

17 Hunt, “Introduction,” 10.

18 Kellett untangles the ties that linked Estienne to Aretino within the French court. Kellett, “Two Anatomies,” 345.

19 Charles Estienne, De dissectione, 276.

20 Kellett, “Two Anatomies,” 344–5; and Talvacchia, Taking Positions, 164. See also Monique Kornell, “Rosso Fiorentino and the Anatomical Text,” The Burlington Magazine 131, no. 1041 (December 1989), 842–7; and D. Kenneth Keele, “Leonardo da Vinci’s Influence on Renaissance Anatomy,” Medical History 8, no. 4 (October 1964): 369.

21 Talvacchia, Taking Positions, 166.

22 Kellett, “Two Anatomies,” 344.

23 Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 185.

24 Plato, Symposium 190c–e, in Selected Dialogues of Plato, trans. Benjamin Jowett (New York: Modern Library, 2001.

25 Ibid., Symposium, 190e–191d in Selected Dialogues of Plato.

26 Ibid., Phaedrus, 250a–252c.

27 Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. (Basel: Ex officina Joannis Oporini, 1543).

28 D.T. Starnes, “The Figure Genius in the Renaissance,” Studies in the Renaissance 11 (1964): 234.

29 Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier, Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge (Cambridge: The MIT Press), 330.

30 Estienne, Dictionarium, 239. Translation by Dewitt T. Starnes.

31 On Estienne’s description of the spinal cord, see Antoine Augustin Renouard, Annales de l’imprimerie des Estienne; ou, Histoire de la famille des Estienne et de ses editions (Paris: J. Renouard et cie, 1843), 356; and Gernot Rath, “Charles Estienne: Contemporary of Vesalius,” Medical History 8, no. 4 (October 1964): 357.

32 Roberts and Tomlinson go further to estimate that the dissected areas comprise “no more than one-fiftieth of the printed area.” Roberts and Tomlinson, Fabric of the Body, 172.

33 Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 12.

34 For an example of Vesalius’ symbolism, see Sawday’s discussion of his frontispiece. Sawday, Body Emblazoned, 69–70.