1.6

Gunnar Asplund: ‘Pictures with Marginal Notes from the Gothenburg Art and Industry Exhibition’, 19231

By 1923, Gunnar Asplund was already a leading figure in Swedish architecture and one of the main authors of the classical revival known as Swedish Grace. He and his colleagues were also the editors of the journal Byggmästaren, for which he wrote this article about the temporary buildings by Ahlberg, Lewerentz and others at the Gothenburg Art and Industry Exhibition of 1923. We include it here because of the attention given to experience of the spatial sequence and its visual effects.

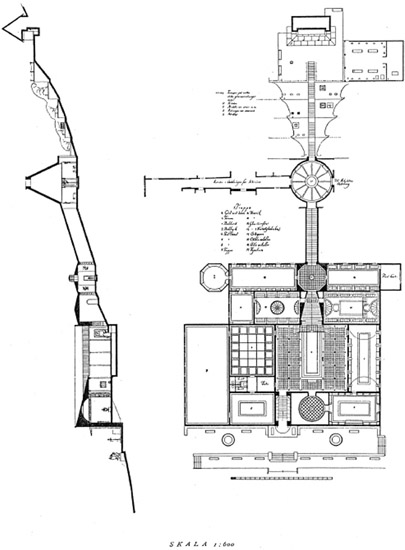

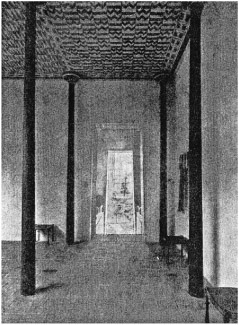

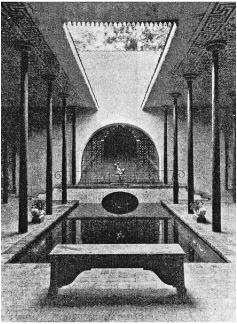

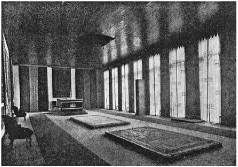

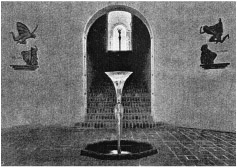

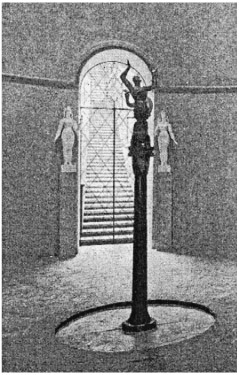

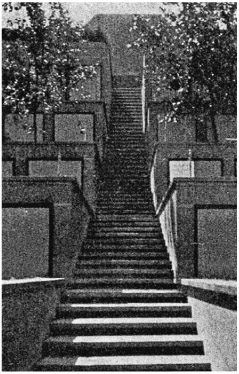

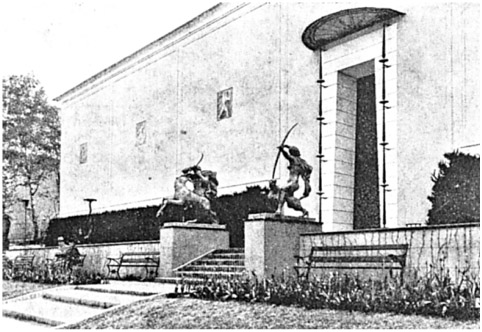

The buildings in the exhibition area are even now being torn down and cleared away, but let us save one complex for memory and for enjoyment. The pictures have not been shown before in this magazine, and the architectural power which gives them value doesn’t end with the summer. The Art and Industry building by architect Ahlberg, the Crematorium Building by architect Lewerentz, and the buildings for the workshop by Lewerentz and Wernstedt were not special for their size or ingenious effects, but because of a certain quality which one would like to believe is today’s and tomorrow’s willpower in our developing architecture. But let us enter. We went past the Art and Industry’s façade which was beautifully located against the greenery under the silhouette of the rock (Figure 1.6.1). It had good restful proportions but the addition of signs and reliefs demanded by the exhibition organisers have reduced its clear rhythm and character: we have stringent demands! In the Interior, however, the given of a strong uphill slope has resulted in a clear rhythmic configuration which is the hallmark of good architecture (Figures 1.6.2 and 1.6.3, plan and section). The columned court with its impluvium and the straight long central staircase, up which one circulates with groups of rooms on both sides at increasingly higher levels, is a brilliant architectonic idea. It is practical because of the clear orientation it gives. It is also refreshing and full of good feeling with its diversity, its fountains, its beautiful views of water and sky: note the joyful rest of the columned courts which is achieved by a clear shape, by locating the main entrance not on axis with the staircase but in the corner (Figure 1.6.4), by the peaceful rhythm of the columns and the splashing of the water (Figure 1.6.5). Note the energetic liveliness in the staircase, the enclosed serenity in the exhibition halls (Figure 1.6.6), and you will find that the beautiful change between them in proportion and character is the foundation to the pleasantness of it all. It is strange that the long staircase does not deter but attracts. Perhaps it was made a bit too narrow. It was difficult because of the crowd to catch the beautiful view, and the round openings in the walls did not really fit with the Egyptian lines of the rest, but the staircase delighted with its directly aligned landings beautifully shaped as octagons and circles. Especially I want to remember the crystal of the fountain and the beautiful terracotta reliefs by Ivar Johnsson (Figure 1.6.7) and the interesting cupola room with the light opening above and with the sculpture of Triton, who greets the incoming light with raised arms (Figure 1.6.8). The room sequence like a string of pearls on the central axis beautifully connects up the exhibition. . . . There was no cold or boring exhibition atmosphere in these rooms but rather a certain bourgeois cosiness. They had fine proportions, tasteful colours, and were cleverly arranged for the exploitation of optical effects. The lighting was exquisite. . . . When we progress further through the doorway under the cupola we find a Jacob’s ladder in the light against us leading up to the plateau of the crematorium (Figure 1.6.9). Here is a clear monumental idea: this staircase with its terraces of graves in the outside air: you really wish you were on your own with an open view, not blocked by the backs of other visitors. The original idea with the rising terraces and the increasing gradient of the staircase augmented one’s expectations. Up at the top on the magnificent plateau one is rewarded with wide views over the roofs like a fairytale city. The building before you has fine proportions and massing but is not entirely convincing as a termination. How would it have been without a building at all, but with the open sky beyond the staircase?

Figure 1.6.1 Gothenburg Exhibition 1923, Art and Industry Pavilion by Hakon Ahlberg, main entrance. All illustrations in this section are reproduced from the original Swedish article

Figure 1.6.3 (right) Art and Industry Pavilion, plan

Note

1 Article in Byggmästaren, 1923, pp. 273–8, translated by Eva Berndtsson and Peter Blundell Jones in 2002 and shortened to exclude the text on the workshop buildings, which would have doubled the required illustration.