The Kassel Theatre project of 1952, designed in collaboration with leading landscape architect Hermann Mattern, was a milestone in Scharoun’s work but also his saddest loss, scandalously dropped after detailed development and a start on site. It won the competition outright, much praised by the judges, and was developed for construction. Work began on digging the foundations, but then the bases of old fortifications were found, and it was stopped. Meanwhile, the city authorities had secretly developed an alternative scheme by local architect Paul Bode, who had not even entered the competition, and that was built instead. It caused Scharoun, not only the loss of his most important collaboration with Mattern, but also a loss of credibility, for, in justifying their dishonest move, the municipality’s officers claimed technical shortcomings that were, in fact, never put to the test. Scharoun’s contemporary text reveals concern with movement both inside and outside the building, for the theatre’s approach and relation to the city were part of the arriving audience’s unfolding visual, spatial and haptic experience, which continued in the foyer and entry to the auditorium. The extract opens with a discussion of the city’s history and the origins of the square Friedrichsplatz in which the theatre was to be situated.1

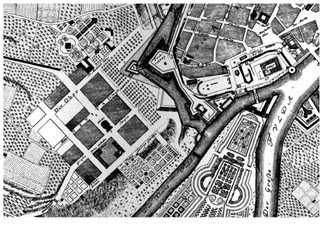

The Friedrichsplatz area of Kassel was formerly the zone of negotiation between two clearly laid out city-cells. Naturally the development of this free area was conditioned by topological and technical demands, but it occurred in a period when the necessity of defining such city-cells was still present, along with consciousness of the essential conditions. So the later Friedrichsplatz grew in the ‘void’ left between two individual gestalts: between the medieval town on one side and the Baroque new town on the other, each obedient to the rules of its period (Figures 1.8.1 and 1.8.2). In the formal design of the Baroque town the Duke’s concerns found expression, so in developing what had been the ‘void’, the Duke’s interests became increasingly dominant, that is to say it became a formal part of the Baroque new town, obedient to the new town’s rules. In the establishment of the new boundary, the medieval town was therefore fronted by a stage-set. But the Friedrichsplatz was initially no closed square, for the ducal influence was more a presentation of the Duke’s power over the increasingly managed bourgeois class, which was shown by the ‘suppression’ of the image of the bourgeois medieval town. So begins the tragedy of the square, which in this early condition was just a piece of landscape and a parade ground. This ‘suppression’ also applied to the adjacent Ottoneum [an early theatre], which arose during the period of the Baroque new town, but was in its content more dedicated to the spirit of the medieval town.2

Figure 1.8.1 Plan of central Kassel in 1742. The medieval town on the right still has its fortifications, and the Baroque new town on the left is identifiable by its grid. Friedrichsplatz is developing between the two, the Ducal palace, later Auepark (valley-park), is bottom right betwen rivers

Source: Adaped from period maps available online

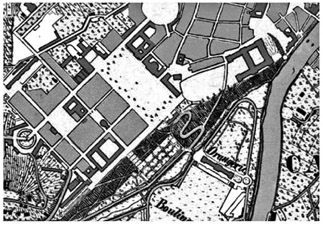

Figure 1.8.2 Plan of central Kassel in 1835. By now, Friedrichsplatz has been formalised, with classical façades redefining its east side, but it remains open to the south

Source: Adaped from period maps available online

If we wish to remedy the blocking off of the old town, whose layout is undoubtedly of historic significance, the recovery and reintegration of the Ottoneum must also be a priority, which belongs in its essence to the area of the medieval town. The position of the Zwehrenturm [an old city gate tower from the fourteenth century] and the open space formed between the Ottoneum and the Zwehrenturm make an effective prelude to that special and characteristic spatial order, and – following tradition – can exemplify the territory of the medieval city-cell.

The creation of a new layout will not be a matter of conserving the falsified wholeness of the square, but rather of finding balance between three contrasting elements: the medieval city-cell, the Baroque new town, and the connection with the landscape beyond. What we mean by the latter needs explaining: the ‘void’ was originally an integral part of the landscape with unbroken visual contact towards the valley. Once this is understood, one sees its elementary essence as a free space with its large dimensions and the fluid treatment of its surface. So a sequence of street spaces leading from deep within the town needs to be developed, and the order of these street spaces must be determined in relation to the general layout and the form of the buildings, then further considered in connection with the transition between the square and the valley, permitting recognition of a more dynamic as opposed to static treatment.

Although the connection with the dynamic essence of the medieval city has obviously been disrupted, the forming of spaces can still retain something of its essential dynamism, even if this needs to be combined with the gestalt means of a geometric coordination system. In addition, the economic development of the city and its new traffic demands are influences on the development of the square that cannot be ignored: for it is becoming so divided by major roads that its built unity is disrupted. So in place of the old aristocratic order a new ordering must be found. Our time brings interactions between the themes of organic and geometric organisation – a struggle between traditional and landscape-related forces. This leads to a mixed deployment of powers, for on the one hand interrelated focal points must be developed, while on the other axes connected with these foci must be added which are appropriate to our lively but highly problematic period. The landscape provides focal points that are aspects of the Duke’s courtly society. Its structure expresses the social order of those times: it is a place that in the form of landscape-bound organs makes an original lively reference to the functions and the environment.

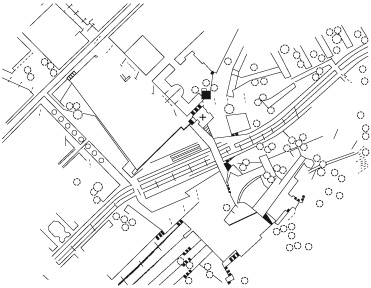

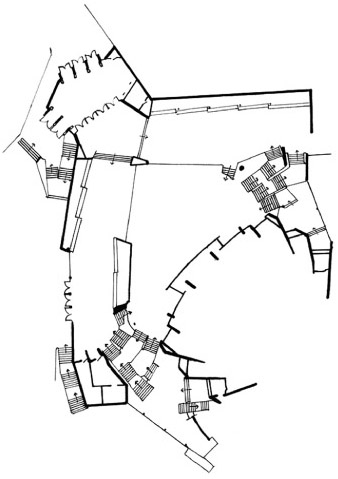

Our new, contemporary, arrangement of place and form (Figures 1.8.3 and 1.8.4) attempts on the one hand to restore the connection with the wider landscape, while assuring that, as the new buildings are added, corrections are made to increase the comparative scale. On the other hand it allows the close connection with the Auepark to be established, in keeping with the new and much broader social function of the park. But while in the eighteenth century a lively interaction of old and new themes made the whole layout attractive and meaningful, the nineteenth century brought this to an end. Hasty technical and economic development – and especially development of the industrial quarter after 1866 – no longer allowed contemporary changes to develop the city’s structure in a responsive and organic manner. With the technical and economic development, the process of making insights about the whole and of finding forms could make no progress. Then, with the return to historically derived forms, concern shifted away from visions of the whole towards narrow-mindedness, seeing only the fragment locked into its own limited situation.

It is characteristic of this age that economically important developments are unprecedented in scale and are allotted enormous sites, so that for example a single industrial complex can take up more land than was needed for the entire requirements of a medieval town. But this occurs – as if the overscaled degree of expenditure must be compensated for – at the expense of facilities for the general public. Here everything is very constrained and meanly organised. But, for public buildings too, site boundaries and site areas need to be considered. The landscape is given over to the service of technical developments, just as society and the law have to adapt themselves to technical necessities.

And yet valuable structures of a cultural or natural kind could in future be rescued from the arms of this technical–economic development. Our view addresses the relatively narrow area in which decisions might yet be made with some certainty and accomplished within a reasonable time. So it must be understood as a phenomenon of

Figure 1.8.3 Plan of the intended reorganisation adding the new theatre, by Scharoun and Mattern. This and earlier plans are set out north to top and the rectangle of Friedrichsplatz appears diagonally, the valley of the river Fulda bottom right

Source: Adapted from published site plan, original in Scharoun Archive, Akademie der Künste, Berlin

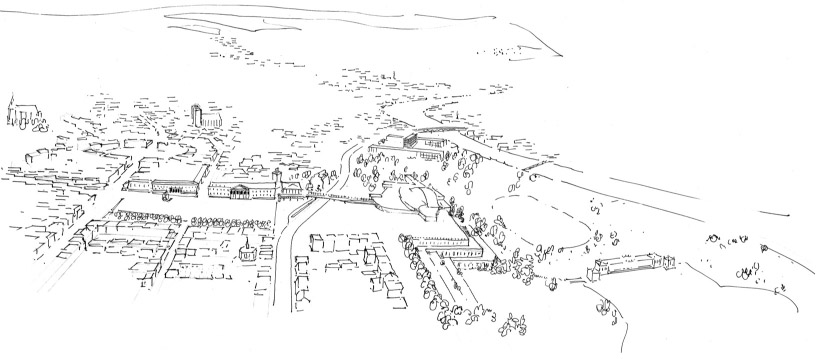

Figure 1.8.4 (above) Bird’s eye sketch of the whole situation, seen from the west, with the Fulda valley on the right and Friedrichsplatz on the left, dominated by the classical façade of the museum. The lower parts of the theatre were to be terraced into the hill, creating a platform with the valley view, and a pedestrian bridge led over the main road into the theatre

Source: From original in Mattern Archive, Technische Universität Berlin

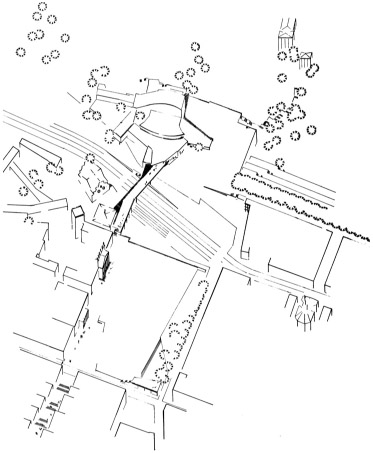

Figure 1.8.5 (left) Isometric projection of Friedrichsplatz with the new theatre top left (north is at 8 o’clock)

Source: From publication in Bauwelt 3 November 1952

Direct on the axis closing the falsely reconceived square was placed the Wilhelmine Theatre [the previous nineteenth century building]. But it has now gone, and it is again a remarkable phenomenon of our time that we have the courage for a consequent and history-conscious realisation. As the immediate landscape relationships have been destroyed, there is no way to add a screen wall of convincing potency that could bring together Man and Nature, Autonomous and Heteronomous, in a new and tense relation. Here, aesthetic concerns founder under a necessary brutality.

Since the Wilhelmine Theatre has fallen, the way is clear to create a new arrangement that reconciles the spatial and landscape givens with expressions of the new social structure. The planner must work as follows: first make an inventory: to investigate the landscape in its surviving worth and to incorporate it in the general frame of planning, to examine the existing and planned developments, to understand historic townscape areas in their living, organic relationships to each other, and to place new elements in relation to them; then, to consider the traffic system in its differentiation and as a technical means at the service of the Gestalt. For the placing of the technically and functionally conditioned through-road is bound to influence the structural form of the city, and if the city is not to be divided and destroyed, decisions must be made as to what is worth keeping and which elements belong together, despite recognising the inherent divisiveness of the task.

With the help of the through-road, the rediscovered void that was the square can be divided into three parts: the terrace looking out over the Auepark, which stands on the remains of the old theatre, the road expanded to become a station for cars, and the retained representative square, placed directly next to the old town and centred on the Fridericianum museum (Figures 1.8.4 and 1.8.5). Into it flows the pedestrian street arriving from the station, which leads across the bridge to the theatre, the terrace and the park beyond.

Thus do the many demands and essential conditions resolve themselves as if spontaneously. The technical/functional starting point can be solved in a way that organically unites the givens with the set task: the way to intuitive vision is open, and what follows on can take place as Pascal put it: ‘I could not have sought you, Lord, if you had not already found me’.3

The town planning solution as discussed leads to a clarification of questions of structure and Gestalt on the grounds of overall relationships and immediate conditions. This is one planning process. The other, more specialised, consists of the development of the focal point itself, of the organ developed according to its being [Wesen] and again in response to local conditions. On this issue something must be said of the theatre itself.

The large theatre is conceived as an auditorium space, but in such a way that the differentiated conditions of action for the players and spectators in their contingency as Sein und Schein [being and image] are brought together and induced by the formal arrangement to confront one another. The realisation of this interaction also provides the means to create the necessary intimacy. It must free itself from the tradition of courtly representation. In order better to raise the opposition between Sein und Schein [being and image] to consciousness, the audience will be brought in not from the side but from the rear. The encouraged intimacy also serves the purpose of bringing the spectator into stronger contact with the acted or poetic event, insofar as this can be done by means of a builderly or spatial kind. The particular meaning of different performances can be expressed through many variations – in quantitative terms by a variable room. By means of the specially altered atmosphere and appropriate handling of scale it will suggest the other situation and so through experience encourage a concurrence of thought . . .

[Text on theatre staging omitted]

So these aligned conceptions – in spatial and theatrical terms – provide a premise for the presentation of a lively confrontation between the world of Schein [image/appearance] and the world of Sein [being]. Spatial linkages, matters of scale, depth and width – as with the structure as a whole – follow their own being/essence [Wesen].

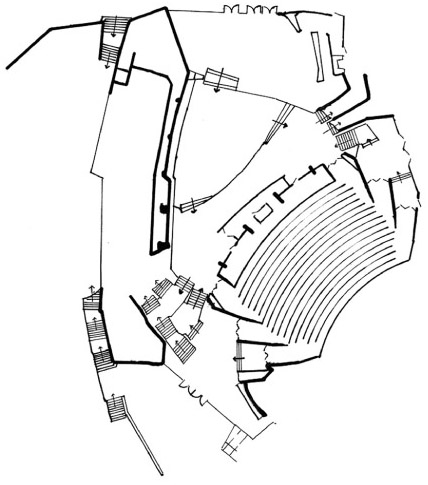

Figure 1.8.6 (left) Plan of theatre foyer, revised version, lower level (redrawn and turned to match site plans)

Figure 1.8.7 (right) Plan of theatre foyer, revised version, upper level, with arrival off bridge top left (redrawn)

Source: Part plans, redrawn by Peter Blundell Jones from originals in the Scharoun Archive, Akademie der Künste

The guiding of spectators over the footbridge or from the dropping off point in the street below it, then on through foyer and cloakrooms into the auditorium, is not just functional, but serves their experience [Erleben] (Figures 1.8.6 and 1.8.7). All circulation and social rooms are optically connected to each other, while each retains its own identity. The rooms for movement unfold in the core-defining representative spatial progression, which includes foyer, refreshment room and smoking room. The refreshment room faces the front garden, the smoking room the valley, also open to the wider landscape. The enclosed court serves as yet another element to free up and enrich the spatial sequence.

The social task of the building is expressed additionally in the use of the theatre as festival site for the city. Therefore, the provision of daylight is included, with help of a skylight, and in front is an ambulatory, along which a promenade can be made in favourable seasons with a view across the valley. The necessary rooms for the artists, administration and business are given their own forms but assembled around a point of communication. The parts of the building are so laid out in response to ground and environment that the natural and the planned can combine in a new unity. To make this evident and understandable a path is intended from the terrace over the back stage and on down into the Auepark. Passage through the buildings seems to me above all an important means of integrating them into society, by visual means, and by passing beyond the visual.

Notes

1 Extracts from a text by Hans Scharoun in Pfankuch 1974, pp. 205–12, first published in Bauwelt 1952, vol. 44, p. 173ff. This translation includes most of Scharoun’s published text and aims at fluency. Not only is one obliged to change the structure of German sentences to make readable English, but one also has to choose between metaphors that lack a precise English equivalent. Scharoun tended to use somewhat abstract metaphorical language, evidently enjoying the ambiguities, but, if translated too directly, it can merely seem vague and imprecise. I have tried to catch its spirit rather than following the original slavishly.

2 The Ottoneum was a small theatre at the corner of the medieval town, preserved today as a museum. It stands at a skewed angle in relation to the Friedrichsplatz, and therefore was seen by Scharoun and Mattern as holding a mediating role [ed.].

3 This seems to be a German version, if slightly altered, of: ‘Console-toi, tu ne me chercherais pas si tu ne m’avais trouvé’, Blaise Pascal 1623–62, Pensées 553, section VII [ed.].