1.4

Hermann Muthesius: Wie Baue Ich Mein Haus

Hermann Muthesius is best known as the author of Das englische Haus, a three-volume study published after his sojourn in Britain that was the best contemporary record of the Arts and Crafts architecture. However, he also designed many houses himself in the Berlin area and was first president of the Deutscher Werkbund, and so a contributor to the modernist breakthrough. His book Wie baue ich mein Haus (How I build my house) of 1917 was intended for the guidance of clients, particularly for those moving out of the city to suburban locations. In its various chapters, there is much concern with room relationships and functions, including how one moves from one room to another, but also concentration on the social niceties of a society that still takes for granted the presence of servants. The two chapters included here are 12 and 13, from the middle of the book, about how the house is approached, and then about the circulation within it. Muthesius illustrated it with line drawings of his own work, which we reproduce.

Chapter 12, The route to the house (Der Weg zum Hause), pp. 107–14

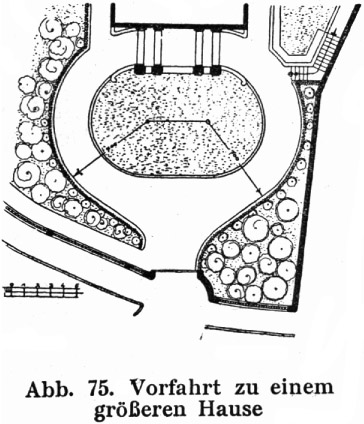

A difficult question that arises in the initial planning of a house is how to make a good entrance. The way one approaches, how one enters, where visitors wait to be received, all this needs the most careful consideration. The entrance does not have to be in the street-front, and can be at the side, but how to enter should never be left in doubt. An entrance at the back is definitely to be avoided. In the case of a large house one must first decide whether a drive for vehicles is to be provided, and if so, there must be room for the vehicles to turn before they leave again. For today’s large and long motor vehicles this is not so easy, as a large vehicle requires the outer radius of the drive to be at least 14 metres, as shown in Figure 1.4.1, and this must be provided even with the house forward on the building line. In this case, though, one can make two gates, one for entry and the other for exit. It is sensible to provide a drive that can take motors for the use of the guests, even if the owner himself uses only a horse drawn carriage.

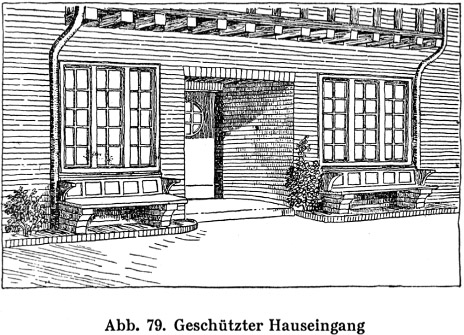

If the house is on a large site and far from the boundary, a porter’s lodge at the entrance is always needed. The porter can then open the gate as the carriage approaches, allowing it to continue on up to the house door. But if the house is near the boundary, the gate can be opened by servants living in the house, although the carriage has to wait as the servant hurries out to do it. A perfect arrival can be obtained with a covered porch (Figure 1.4.2), which allows transition from carriage to house in rainy weather without wetting the feet, but it is an expensive addition only affordable for a large house. If the point of arrival cannot be covered, the best mode of arrival being therefore precluded, it is better to omit such a porch altogether. The whole task will then be made much easier: instead of the main gate, have a garden door, and in place of the elaborate drive, a garden path. As an addition one can build a covered way from the gate to the house, which makes the drive unnecessary. Alternatively one can build a pergola, which when covered in plants at least gives some protection. Planning control demands if the house is a certain distance from the street – usually 30 metres, which is the length of the fire hose – that there must be an entryway, but it does not have to be fully metalled, and a garden gate only 2.3 m wide will suffice.

For good supervision of the entrance it is essential that the servants can see the garden gate from the house, and it is usually provided with an electric latch that can be operated from within. It is therefore essential that servants can recognise who has arrived before opening the gate. This issue must be considered from an early planning stage, to assure that the service rooms gain a view of the entrance. But where will the servants be? Often it is the so-called servant’s room that is given easy access to the entrance and overlooks the gate, but this arrangement fulfils its purpose only if the servant remains in his room, which he hardly ever does. He has housework to do, which takes him to the servery or cleaning room, or into the kitchen, and his own room is used only to sleep. Only in great houses like that of a Duke is it possible to have a servant constantly on watch in his room to receive visitors. Therefore it is in all cases better to make sure that the house-door can be seen from the kitchen, the one room where the presence of at least one of the servants is guaranteed. If the kitchen lies not on the same side as the entrance but to the side, a projecting bay can be provided to allow the servants a sideways glimpse of the approach. This has the advantage that visitors do not have the feeling of being scrutinised by the servants. It may also be desirable to run a speaking tube from the house to the gate, so that visitors can announce their identity.

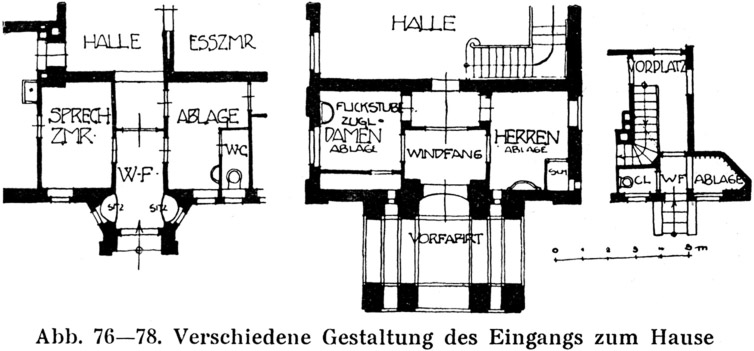

Figure 1.4.2 Various entrance arrangements with waiting places for guests, left, and porte cochère, middle

Once the gate has been opened and the way cleared to approach the house, the visitor proceeds to the house door, where he must ring the bell for a second time. It is most desirable to set the door back a little (Figure 1.4.3), or to provide it with a small sheltering porch to protect the waiting visitor if it is raining. If such a shelter gives more of a feeling than the reality of protection, it nonetheless generates a homely atmosphere and lends the house entrance an inviting impression. To build open steps leading up to the entrance is not recommended, lest in winter they become slippery and cause accidents: a clever designer will usually find ways of accommodating changes of level within the house. The door having been opened and the visitor welcomed, he must wait some minutes before being received: where is this to happen? Precisely in this matter the rules remain rather unresolved in German houses. In blocks of flats the visitor, having handed over his card, has the door off the staircase closed again in his face, or at least reduced to a narrow slot. This always gives the feeling of being neglected, and we have to excuse such bad form as inevitable with the rented flat. But in the case of many one-family houses it is not much better. Here at least care should be taken that the visitor, after the door is opened, is conducted into a small antechamber where he finds a dignified welcome (Figure 1.4.2, compare with Figure 1.4.4). For this purpose the wind lobby can suffice, provided it is well appointed and provided with a seat. This seat is more symbolic than real, for nobody will sit there, but it makes the room welcoming, and conveys the idea that one might spend some time there. When the servant returns, the visitor can be led first into the cloakroom and then to the hall or antechamber. To bring a visitor from the front door straight into the hall and leave him waiting there has the disadvantage that he has in one move penetrated too far, for he still has his overcoat on, and furthermore someone may have been mistakenly admitted to the house who should not be there. For there are also commercial representatives whom the house owner would prefer to see in a special room, perhaps in a waiting room or study next to the entrance, or in a dedicated interview room (Figure 1.4.2). As for the cloakroom, it is important that it has two doors, one for entry from the wind lobby, the other for exit to the hall. This is especially needed for social occasions, even with small groups, when the lack will be felt if everyone has to use the same door to enter the cloakroom as to leave it again, for the participants all arrive and depart at the appointed hour, and those entering will bump into those leaving. Some say there should be separate cloakrooms for men and women, but this is excessive for a middle-ranking house. On social occasions a special room can be set aside for women even on the upper floor, in which case they must pass through the hall. The men, having used the facilities on the ground floor, can then await their womenfolk in the hall. The preparation of such a room, in which a dressing table with sewing kit and other items necessary for feminine attire, used during the kind of social occasions which bring women to a house for several hours, also has other advantages; for the special cloakroom with adjacent lavatory remains private from the men. Almost any other room on the ground floor can serve temporarily as a women’s cloakroom, such as a reception room, children’s dayroom or mending room. This double use then needs to be carefully considered during planning. A dedicated women’s cloakroom for social occasions is an extravagance reserved for the cream of houses and those in which entertaining plays the dominant role.

In the correct arrangement of wind lobby, cloakroom, lavatory and hall there is yet more to be considered. It is not unusual for a door to lead directly from the hall to the lavatory, so that people sitting in the hall get a glimpse of its interior every time the door is opened. Such a layout can only be considered a design error. Often there is a lack of tact and propriety in our hospitality over the presentation of lavatories, especially when the signs ‘Ladies’ and ‘Gentlemen’ are placed too close together. The lavatory is a room whose presence should never be too obvious, but which nonetheless should be easy to find. Access through the cloakroom is always the best solution. Extraordinarily frequent too are halls in which coats are hung, an arrangement to be expected in the smallest houses, but too often also found in middle-ranking ones. It is no pleasure to change galoshes or overshoes there, especially with the storage already full of children’s clothes. Through careful planning it is possible to meet this important need in comfort and dignity even in small houses by adding the necessary side rooms. Figure 1.4.2 shows how wind lobby, cloakroom, and lavatory can be assembled even in tiny spaces, but such a concentration is only allowable for very small houses.

Hardly less important than the placing of the main entrance is that of the service entrance, which should also be overlooked by servants. Whether it is necessary to decide a special route to the kitchen in planning the site, or to branch it off in laying out the floor plan, depends on the circumstances. An excess of entrances makes the whole plot too public, and it is tiresome constantly to have to open and close too many gates. The back entrance to a house should also have an ante-room to divide it from its first destination, the kitchen. A practical measure is to put a small window in the kitchen door through which supplies can be passed without the delivery boy needing to enter. The kitchen entrance should lie to one side, so that traffic in and out does not obstruct the owner, but it is sensible not to remove the owner’s supervision entirely. With a large plot it helps to add a service gate to one side or the other. It is best left without a knocker, and kept locked when not in use.

Life is much easier for the inhabitants if a single key opens not only the garden gates but the house doors as well. It can even extend to the inner doors, to cupboards and furniture. If this is required it must be specifically ordered from the locksmith, otherwise in the usual thoughtless way each door will have a different key and the owner will find himself laden down by a heavy bunch.

This is perhaps the place to say something about the boundary of the plot, even if it belongs more in a book about gardens. Over its design local planners have held a great influence. At first they insisted that the boundary should be kept transparent, to lend a ‘villa colony’ a friendly appearance, and only metal fences were allowed. Later wooden fences were permitted. Then along a small part of the boundary a wall was allowed, at first a third, then half of the perimeter. We are moving now towards the return of the old garden wall. The transparent boundary belonged, along with the front garden behind it, to the period dominated by a concern for outer appearance. A welcoming view for the visitor was the priority, for which the house owner was obliged to make sacrifices. For the owner of a country house it is certainly no obligation to lay out his garden for the appreciation of strangers and to live as if on a stage. Despite the planners’ efforts, the general tendency today is to close off the street edge, even if mostly through the planting of thick bushes or a hedge behind the metal fence, which the planners are powerless to prevent.

The boundary should be laid out from the first with these considerations in mind. A solid wall has many advantages, though it is expensive. A cheaper alternative is a wooden fence, but the fence-posts can at least be set on concrete bases, for if set directly in the earth they rot in a few years. The connection between timber and concrete can be made by casting iron straps into the concrete. A narrow gap should be left between the post and its base to prevent rot. Wooden fences are cheaper than even the simplest iron ones. The cheapest boundary is the wire fence, but the effect is so horrible that it can spoil a whole house. At best it can provide support for thick planting. In other countries a living hedge has been used with advantage, which also has a pleasant appearance on the street. The best boundary to a property, though, is undoubtedly the garden wall, which should surround the entire plot if the conditions allow it.

12 Circulation within the House (Verkehrswege im Hause), pp. 115–19

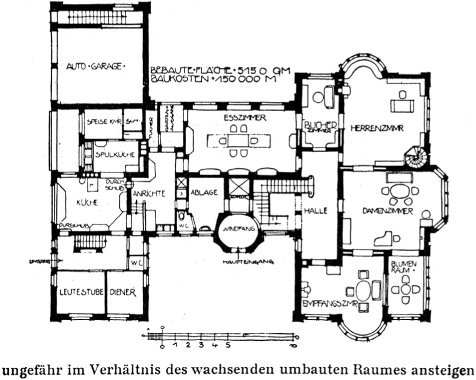

Two parties inhabit the house who are well known to each other but belong to different strata of society: the gentry and the servants. An essential task of house design is to allow both parties to move freely as they wish, but to divide the circulation of the gentry from that of the servants, while retaining all necessary connections for the maintenance of domestic life. This basic division is no general rule intended to disadvantage the less fortunate, but is rather something forced onwards by the growing independence of the lower classes. The ancestral relationship, by which gentry and servants ate at the same table, is long past. Today the consciousness of the lower condition would feel such unnatural mixing as more of an imposition than a benefit, and mutual existence without conflict is the goal for which both parties strive.

It is therefore important as much for the gentry as for the servants to keep the room groupings separate. Both groups must take care, though, that the necessary connections can be made at every point along the border. The connections of the servants with the gentry part must allow them to go about their daily work, while the reverse connection requires that the lady of the house is able to supervise them in all their activities. For both parties to retain a tranquil life it is essential that the circulation routes of the gentry do not cross over into the territory of the servants, and vice versa. Daily observation reveals that this is constantly where mistakes are made. For example, it is common that servants must cross the hall to open the door, though we try to make the hall into a reception room [Wohndiele], so this results in an imperfect arrangement. The way to the front door should avoid the dwelling rooms. But there are greater offences. In the ground plans of Berlin tenement flats there is a room that links the rear service rooms with the front living rooms and also leads to the hall door, the so-called Berliner Zimmer. Here again one finds an arrangement of antiquated origin, which could only have arisen because the Berlin tenement was managed by unsuitable authorities. But what should one say when such crossroads of rooms are built in freestanding country houses, and even published by their authors? To transplant the most questionable error of the Berlin flat can only show a shocking lack of design skill. The fact that in the 18th century the rooms in the linear wing of a castle were usually strung together without an adjacent hallway can scarcely excuse such bungling. The living conditions were then different. It seems they tried to overcome the problem with screens, to make the movements of servants less obvious to those in the room. But it is today an essential principle that every room be enterable from an anteroom or hall. The door cuts off the room from the service side, so is much more important than the doors between the rooms. Only service rooms such as the kitchen or scullery do not need such antechambers, for they are already fully dedicated to service and linked with each other.

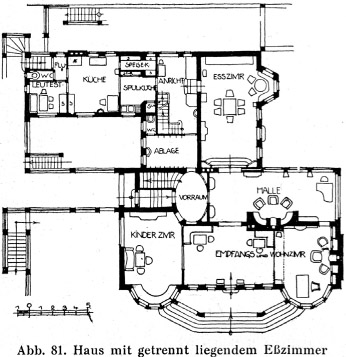

The room that requires the liveliest traffic to and from the service rooms is the dining room. The laying and clearing of the table, which takes place several times a day, requires a more protracted presence of servants in these rooms. It has therefore become customary for the dining room to be used not as a living room but only for eating, unless there are compelling reasons to the contrary. Today’s dining room is in terms of location the most restricted room in the house. Since it needs a close connection with the kitchen, it naturally must be close to the service rooms. When there is a hall in the middle of the plan, it is a good strategy to place the living rooms on one side and the dining room on the other along with the service rooms (see Figure 1.4.5). Then the whole service operation, which can be obtrusive during the laying and clearing of the table, is removed from the living rooms, and crucially the odours are also constrained to the smallest area. Such an arrangement is especially advantageous on social occasions. It means that one must cross the hall when going to dine, but this is no drawback, rather it is an advantage, for it brings the hall, on which much design effort may have been bestowed, more of a central role, and when the hosts are entertaining it makes the progress to table a truly festive event. As for the often-desired direct connection between living and dining rooms, the reason generally given is further use of the dining room on social occasions following the meal. But when the dining room has been cleared and can again be part of the circulation, it can equally well be reached via the hall. In any case the advantages of the separate dining room exceed the disadvantages, which incidentally are more imagined than real.

In the design of the house plan the two aspects of dwelling and entertaining intersect easily, but many clients put too much stress on the latter. They are used to city living, and to considering the duties of entertainment first in choosing a dwelling. This concern for entertaining has influenced the design of the house plan in a particular direction, namely the connection of the reception rooms by sliding doors. These doors then only serve their purpose when the house is full of people and it is advantageous to make several rooms, as it were, into one single room. But when the family members are gathered in a small circle, nobody will want to open the sliding doors to the second or third room and so to extend the space: they are more likely to want to make it more intimate.

Special consideration must be given to the relationship of both gentry and servants’ territories with rooms for the children. It is not always easy to find a suitable place in the plan for the children’s playroom. It should naturally not be far from the living rooms, but it is also important not to place the source of noise from youthful activity too close to the adults’ reception rooms. A position not far from the kitchen has the advantage of easier service, for there tend anyway to be frequent routine domestic tasks in attending children. But in this matter one is seldom free, for as in other parts of the house, orientation matters, and should be a primary concern. It is most desirable to give the children their own lavatories and even their own entrance. The children’s lavatory cannot always be kept as orderly as a general one that is also used by guests, and it should contain its own wash basin.

The consideration of the circulation of servants within their own area is very important. The best functioning of the service area of the house cannot be considered as achieved while things are lacking there. The sequences of service rooms, and the way they are laid out to lead from one to another, are matters of the first importance in a well laid out house. Here especially the critical opinion of the mistress of the house must be sought.

The details of the service rooms will be dealt with later, but something should here be said of the accommodation of servants, that is about their sleeping quarters and day rooms. Obviously it is desirable not to place their recreation rooms too far from their workrooms. And since the servants’ bedrooms are usually in the attic, and therefore far from the work rooms, it is a great relief if a small servants’ sitting room can be placed next to the kitchen for daytime breaks. Then the servants’ bedrooms are merely bedrooms, for a free evening can be spent in the servants’ room. As for those other quarters a difficulty arises if both female and male servants are present. The bedroom of one male servant can be conveniently placed in the ground floor, with the advantage that the house is better protected from larceny. It is recognised that thefts seldom occur from those houses in which a man sleeps on the ground floor, while thefts are invited if all residents are in the upper floors. The bedrooms for female servants are best placed in the attic close to the service stair. Guest bedrooms in the attic, as often mentioned, must be fundamentally and visibly divided from those occupied by maidservants.