In Retirement

Mary left the Ministry of Education in 1972 after a disagreement that had developed over plans for a new primary school. Ex-colleagues recall that Mary started to work on a sketch design for the new school while two other architects in the A&BB also began work on the project in the same room. There was some basic disagreement about the projected educational groupings. Mary who had always regarded educational planning as her forte asked one of the HMIs for advice, but the others continued unabated. After taking her scheme to the LEA involved, it was the others’ sketch plan, not Mary’s that was agreed. On returning to the office later, Mary found that the architects had taken their scheme to another room. Shortly after, Mary left the MoE.1

This episode illustrates some tensions that surrounded school planning at this time, generated by a significant critical dismissal of progressivism in general and child-centered planning in particular from a right-wing oriented press. This period is sometimes referred to as the end of the post-war consensus.2 Two years earlier, The Black Papers had been published and their views which presented child centered teaching techniques as betraying the potential of children were publicized via the popular press and were widely discussed. According to these critics the abandonment of selection by examination at the end of the primary stage had been destructive; discipline in schools had been eroded; and new teaching methods had failed.3 In contrast, the views of HMI were more telling. They argued that Comprehensives had yet failed to establish a unique and fitting identity and had imitated grammar schools instead of developing their own kind of curriculum; examinations dominated the curriculum unreasonably; and virtually all schools let down the less able pupils. Both Mary’s and HMI points of view which had developed steadily over decades since the war were shouted down by the shrill and powerful voices calling for a return to traditional values. This was to herald a change in this direction under successive Education secretaries of state beginning with Margaret Thatcher, from 1970 to 1974.

Mary was nevertheless wedded to a belief that the principles and values of primary education could be usefully applied in adapted form elsewhere in the system, be it in the nursery or secondary school. Others disagreed and sought to distance their designs from this approach which was by now coming to be seen as dated. Given the circumstances of her retirement, it is perhaps not so surprising that Mary’s next tasks were to help to plan primary schools in Wales, to develop primary bases for teacher training and to advise on the planning of pre-school environments. In all of these she remained committed to her ingredients of design in what she saw as the best interests of children and their teachers.

DESIGNING FOR THE UNDER-FIVES

The provision of appropriate high quality environments for pre-school children has been struggled for over the course of the twentieth century in Britain and continues to be a vulnerable area of public service. As we have seen, Mary Crowley worked on nursery environments early in her career and returned to the issue in her retirement at what was an interesting moment in the development of ideas about the development of infants and appropriate early years education. In part this was due to changes in the Higher Education sector that helped to promote the impact of educational psychology. During the early 1970s, through the work of leading sociologists and psychologists, interest in pre-school age children shifted its focus fundamentally. Prioritizing the material provision of care and welfare through attention to light and air now appeared to be less important than understanding differences in cognitive development. Preparation for school now called for more attention to the individual mind and less to exercising body and mind together in an atmosphere of freedom and security.

There was an international context to this trend as nations attempted to get ahead of one another at what was the start of an era of comparative educational rankings.4 In 1965, the Head Start programme was launched in the USA and was visited two years later by English HMI.5 Meanwhile in Europe, the pre-school projects in Reggio Emilia were pioneering a significant new approach to pre-school education with a clear emphasis on the material environment. But Britain appeared to be following the American model which placed more emphasis on the science of child development than the art of designing cultural and material structures to support and enhance well-being. One could argue that in this climate Ralph Crowley’s notion of ‘the whole child’ was becoming harder to fight for.

In England, sociologists and psychologists began studying this age group closely and their work began to have impact under the Conservative political administrations that dominated the period. In 1974, Barbara Tizard at the Thomas Coram Research Unit in London, produced a research review surveying pre-school provision in the UK concluding that more formal pre-school programmes had measurable impact on later educational outcomes.6 The sociologist and linguist, Basil Bernstein (1924–2000) was conducting research at the Institute of Education at this time and his work was beginning to emphasize the significance of language development in educational achievement especially in relation to social class.7 These research initiatives pointed more to the role of formal pedagogy in improving children’s level of achievement in basic academic subjects which teachers, parents and government were united in wishing to improve. Together with the impact of cuts in expenditure on capital projects in education, the climate was not good for educators or architects of Mary’s persuasion.

The British government was coming under pressure to provide statutory services for the under fives. The response came in 1972 when the education secretary Margaret Thatcher produced the White Paper, ‘Education – a Framework for Expansion’ which included in its provisions, a recognition of the need to expand nursery places. While there was a general acceptance that funds should be made available for buildings, less demanding on the exchequer was to accept the new orthodoxies around growth and development. As Dr E. M. Parry, an expert in pre-school provision explained,

there used to be a lot of talk about ’withdrawal’ and need for cosy corners and screens to go behind … now we are talking more about cognitive growth and language.8

The Medds met with Dr Parry shortly after the publication of the government’s White Paper to discuss pre-school design for education. Parry was at the time involved with the Schools Council Pre-School Education Project which was investigating in detail the state of provision. In the research carried out, 17 films were made documenting practice across the country. At their meeting they talked about the importance of providing means to develop sensory discrimination through smells, touch, taste, sights and sounds but also about the necessity in the present climate to present the case for pre-school specialist provision at all. It was, they agreed, often depicted as being too expensive, too isolated or as being an ‘artificial life’, neither home nor school. Mary’s remarks appear to suggest that she saw the nursery as having a specific and particular role to play and that therefore the design of such should be afforded especial care. But as ever, Mary and David stressed the primacy of ‘the people and the work, not necessarily the building’ as they decided, in discussion with Parry, particular sites to visit and observe ‘remarkable’ work carried out by inspiring teachers.9

The contents of a special issue of The Architects’ Journal, ‘A Fair Deal for the Under 5s’, suggest that architects were becoming aware of changing attitudes to the provision of nursery education.10 The journal presented images of pre-school children in environments that mirrored that of Eveline Lowe, especially in the kiva. ‘The nursery areas are usefully split to accommodate the noisy and quiet, tidy and messy activities, with a step up into the quiet area to punctuate the demarcation.’ A new emphasis on the rights of the child to determine their own activities is evident. With reference to the built in bunks, the journal stated, ‘children are no longer put to bed at set times during the day but can go and lie down at any time if they feel tired.’11 Although the words describing this environment are not Mary’s, they very easily could have been and she would have agreed with them.

Mary had developed her notion of the ‘ingredients’ required in good educational planning of learning environments and extended these to pre-school (Fig. 8.1). We can see her ideas made plain in a detailed sketch plan entitled ‘some planning ingredients’ which she completed in March 1972. Here the ingredients of planning were set out as HQGPVM or ‘home group’, ‘enclosed (quiet or noisy)’, ‘general and flexible’, ‘particular (equipment, services)’, ‘covered work area’, ‘constructions, acting, music etc (small groups)’.

8.1 Mary’s plan of an infants school environment ‘300 children: 3½ to 7 years’ illustrating her planning ingredients, 1972. IOE Archives, Plan ‘300 children: 3½ to 7 years.’ Photograph João Monteiro

As in environments for slightly older children attending primary schools, according to this planning template there should be provided a variety of sized rooms to serve different functions. Mary was aware that designing for the under-fives meant providing for the whole community. There should be larger meeting rooms to hold sales of work, concerts, assemblies, exhibitions, films, acting and movement; small ‘workshops’ for repairs, making things and storage; a small pantry for drinks and snacks; ‘medium’ rooms for social events, committees, old people, students, staff and gatherings; small rooms for secretarial work, committees, interviews, doctor, welfare worker and related staff. Spaces would provide opportunities for shared small group activities to support ‘dressing up, puppets, music making, transport, jumping, climbing, rolling, building and constructions’.

The outdoors was of course not to be neglected where Mary suggested a range of simple devices to support active and imaginative play. There should be

grassy mounds and hollows … enough for a child to fit and have the ‘illusion of aloneness’ with grass near by above eye level. There should also be a hard surface area for the oldest to cycle, sandpits – preferably two, side by side with a hard surface in between. A garden court was generally included in plans for ‘animals, fish, water and plants’.12 There should be ample earth for digging, shallow water for paddling and sailing, flowers for picking (nasturtium and everlasting sweet pea were suggested), and small walls and steps for balancing, jumping and chasing.13

These ingredients of design were the foundation for an in-service training course organized by the University of York in 1971 that resulted in a book A Right to be Children, published in 1976. This critically reviewed a range of nursery environments already in place while suggesting, through discussion and imagery, what was important for this age group. Mary also contributed to an exhibition held at Woolley Hall near Wakefield in July 1974. The Exhibition was entitled The Design of Nursery School Buildings.14

As she was preparing her book the now famous municipal pre-schools at Reggio Emilia in northern Italy were getting underway. The first Reggio pre-school opened in 1967 and the first director and inspiration for the initiative was Loris Malaguzzi.15 Less well known is that Malaguzzi knew of the work and progressive philosophy of Mary’s mentor and inspiration Carlton Washburne who had left Winnetka, USA in 1942 to spend several years advising the post-Fascist Italian government on developing its education system towards strengthening democracy.

So it seems relevant to explore the common ground between Mary’s definition of quality in pre-school environments and those that have developed so strongly in parts of Italy in the post-war period, especially since these environments receive such a strong interest among early years specialists and practitioners today. The enthusiasm for Reggio pre-schools is understandable however, since that system regards the built environment as a key part of the education process, this interest has eclipsed knowledge of past initiatives closer to home. This is true in Britain as well as elsewhere. In the USA, early years teachers have also been inspired by the pre-schools in Reggio Emilia but have discovered more recently that their own locality was well known in the past for a philosophy of education that was rooted in the relationship between pedagogy and the built environment.16

In A Right to be Children, Mary was critical of what she found to be less than appropriate teaching and environments provided for this age group and many of her criticisms ring true today as much as they did at the time. She strongly asserted what she considered to be essential in supporting the ‘whole personality of the child’ in their pursuit of play, ‘part of the business of childhood’. She recognized and praised good practice but also identified poor provision and especially disappointing attitudes towards children and the environments provided to support their ‘immense curiosity’.

In suggesting what should be found in the best environments for the under-fives she identified seven zones of activity that could be achieved not so much architecturally but by furniture arrangements made by teachers who understood how to use space and materials pedagogically. These zones were:

Table work: using materials, objects, small scale, not much mess.

Acting: home play, camping, shops, hospitals.

Music: singing and dancing, exploring sounds individually.

Messy work: using clay, water, sand, dough.

Quiet work: looking at books, writing, resting, story telling.

Moving: climbing, swinging, jumping, rolling.

Construction: building blocks, small and large scale undertaking such as engines, buses, boats, houses etc.

Her narrative is always from the point of view of the child in support of their bodily and cognitive needs and she warned against the tendencies, already observed, of teachers becoming taken up with the latest trends or commercial features. The 1970s saw an expansion in the school equipment industry and goods were promoted strongly to teachers as offering them ever more pedagogical opportunities.17 This was the case in the nursery too. The message seemed to be that just as science was producing convincing knowledge about how children learn best, equipment made of new manufactured materials would signify best practice. Mary was disappointed in this trend and was firmly unconvinced. ‘A surfeit of plastic apparatus may look good but misses the point entirely … where is the junk, the improvisation?’ In her book, an image of a play train constructed (obviously by adults) from bricks is presented to illustrate the point that in such a piece of play equipment, adult fancies might be satisfied but for children there was ‘nothing left for the imagination’. Side by side with this, she presented what for her were inspirational and timeless images of children hanging, climbing, crawling and constructing.

As ever, Mary was deeply interested in children’s worlds and saw her work as partly an attempt to release them from the adultization and institutionalization of their habitats. She was convinced from a lifetime of observing children that the best means of preparing children for adult society was ‘by not cushioning them too much but adapting to suit their specific needs’.18 Attention to detail was coupled with specific advice that teachers and parents would find easy to understand. The environment in general for this age group should be full of opportunities for construction, creativity and imagination but will have the order of a good craftsman’s workshop and the stamp of the personality of people working in it. Perhaps reflecting on some of the progressive schools she and David had observed in the USA, she suggested the environment should be largely home made emerging from the teacher’s imagination and the work of the children. An appreciation of the rhythms of children’s natural cycles and the importance of not over determining the environment was evident in her suggestion,

If someone does feel like a nap he can be quite happy to fall asleep on a pile of bricks. What he likes is to get away sometimes though to a comfortable place on his own, where he can curl up – under a table or a rug, in a box or a barrel, along a wide low window ledge with a cushion or two.19

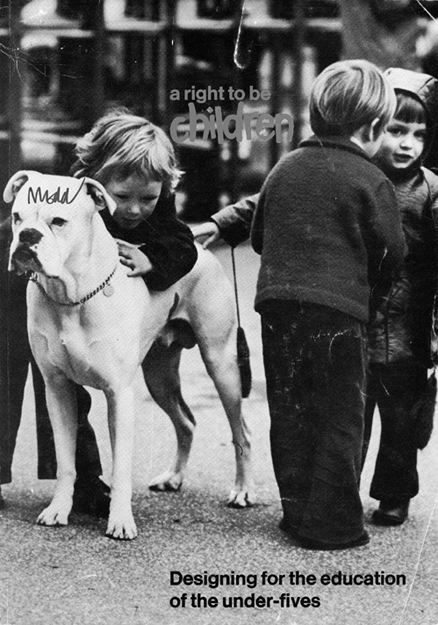

The wide low window ledge had been observed by Mary time and again in her career as being a space valued by children and teachers alike and continues to be so. Finally, the illustrated front cover of the book indicated the tone to be struck – seeing the world from the child’s point of view and their need for close proximity to living creatures. It presented three children playing outdoors, one holding the body of a bull dog, nice and close.

8.2 Cover of book, A Right to be Children (1976). RIBA Publishing

WELSH VILLAGE SCHOOLS

In 1967 the Gittins Report called for a review of the building stock in rural Wales where predominantly small village schools served the scattered population.20 Mary and David, having worked on village schools in the similar demographic of Oxfordshire were well placed to respond to the question of how might small scattered schools be replaced by new ‘area’ school buildings serving a larger area. For two years, 1974–76, Mary and David worked on the ‘problem’ of Welsh village schools; some redundant, some to be refurbished and others to be merged. This was in association with the Welsh Education Office in Cardiff and Welsh HMI Gordon Warren in Wrexham.21 There were two main investigations to carry out: the problem of provision for the under fives in the many small village schools; and the design and building of an ‘area school’ for primary education with a catchment area of five separate schools within a radius of two and a half miles. This was to be explained in a Building Bulletin detailing what could be done. The latter was a sensitive issue where five rural schools were to be closed and replaced by a new larger school.

To research the problem fully, a school was designed and built in cooperation with a Welsh architect from the Welsh Education Office. This was Ysgol y Dderi School, Llangybi, near Lampeter opened in 1976. It was designed for 20 pupils under 5 and 100 pupils of primary age.22 Each had a complement of teachers and a variety of spaces appropriate to the ages of the children, ‘yet another explosion of the standard classroom – not open plan nor deliberately ‘progressive’, but trying to meet current teachers’ needs in constrictive spatial and financial conditions.’23

Christian Schiller, although now also retired, continued to be actively engaged in influencing the development of primary education. In personal correspondence with the Medds he suggested the next big step in primary education was ‘to give children at school, not a new world, but an enlargement of their present world, where mum and dad feel at home as much as John and Mary’.24 Therefore, the buildings should signal connectivity, openness, community and a continued effort to de-institutionalize the school and open its doors. In the 1970s, in the context of a sociological emphasis on endemic disadvantage, there was a flourishing of adult and community education and Schiller and the Medds recognized this development of an idea that had been familiar with all of their lives. Plans of nurseries, health centres and adult education centres found in the papers of the Development Group at this time reflect this trend.

One of the Welsh schools designed by Mary and David was Cemmaes Road Primary. There is a strong Scandinavian character evident in the design and finishing, for example in the exposed pitched roof. Unlike Finmere where the roof beams were exposed, here the roof space was entirely open and timber clad creating a spacious yet warm atmosphere. The large general work areas were divided by means of carefully selected furniture such as cupboards with integrated display units as well as by folding partitions.

8.3 Ysgol y Dderi School, exterior. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/1

8.4 Cemmaes Road School, courtyard. IOE Archives, ME/V/2/1

In furnishing the schools, the Medds were delighted to be able to select locally-woven textiles as window drapes enhancing the distinct character of the buildings.

THE PRIMARY BASE AND TEACHER TRAINING

For 20 years after her formal retirement from the DES, Mary collaborated with Leonard Marsh from Goldsmiths and later Bishop Grosseteste College, Lincoln, on the development of primary bases and other aspects of college accommodation. For this, Mary along with David, was awarded a Doctor of Science at Hull University in 1993.

Many influential figures in primary education in these years believed that the key to any success in radical re-design of school buildings which promoted a view of the child as a creative being was that teachers become ‘spacious’ in their thinking. There was little point in producing schools that through their design and furnishing suggested a shift away from the box-like classroom if teachers had been trained only to imagine themselves working in one. Changes in teacher training were vital to achieve but, as in schools, most professional training took place in college classrooms. Trainees should ideally be taught in model classrooms in order to develop habits and expectations not confined to traditional didactics. Providing primary bases in training colleges was thought to be the answer.

The in-service training courses for practicing teachers held at Dartington Hall and Woolley Hall in the 1960s, as we have seen, incorporated contributions from the Medds as an integral part of efforts to develop the profession. But these were drops in the ocean, so to speak, and an awareness of the possibilities of using space in teaching was not in general part of mainstream teacher education. It was not until after Mary’s retirement from the DES in the early 1970s that together with David Medd, she could tackle this issue with the support of directors of teacher training institutions, first at Goldsmiths in London (1971), and later at Bishop Grosseteste College, Lincoln (1974). Mary believed this work to be of fundamental importance and commented that had such an emphasis been in place in the 1950s, their work at the Development Group would have been even more influential and successful in bringing about change, at least in the primary schools of the country.25

The primary base is a space specially designed to support teacher training. Its purpose and form built on the experience of working with teachers in workshops held at special training courses in the early 1970s. The primary base was initially conceived at Goldsmith’s College in London within the primary wing, under the direction of Marsh and Schiller.26 As Mary explained, the primary base was intended to suggest an alternative pedagogy in learning to teach. It offered

a new element of working accommodation for teacher training and that meant that there was somewhere where small groups of students could work in different ways and have the kind of equipment and organization and planning that one hoped would be suitable from what had been seen going on in schools … (as) part of understanding comes through actually ‘doing’ and not just through ‘talking’.27

One strand in the development of the idea of teachers learning through doing can be found in the work on school furniture that David Medd had pioneered in conjunction with PEL furniture manufacturers.28 PEL made scale models of individual pieces that were designed by David. Eventually, this became a full range with British Standards approval. Teachers taking professional development courses were encouraged to play with model layouts and furniture pieces, always imagining the educational purposes behind their decisions (see Fig. 7.6). So successful were these methods that the idea of the primary base developed to build actual spaces within teacher training institutions partly to provide evidence of an ideal teaching and learning environment and also to enable trainees to experiment with equipment and space before going out into schools.

Mary recognized the significance of the link between the planning and design of teacher training facilities and schools. At Goldsmiths, on the fourth floor of the new education building, Mary worked specifically on the re-arrangement of an area of approximately 222 square meters of floorspace, furnishing it as a base for 60 to 100 students taking the one year post-graduate course. The general character of the area derived from being planned deliberately for small groups working in areas for study and practical work, carrying out what they considered was then best practice in prospering primary schools.

When Marsh moved from Goldsmiths to become principal at Bishop Grosseteste College, Lincoln he soon after invited Mary and David to carry out similar conversion work to the training premises there. This was the beginning of a collaboration that continued over the next twenty years, supported by further changes in staff at Lincoln. In the mid 1980s George Baines and Judith Baines, moved from Eynsham School in Oxfordshire to take up posts at Lincoln. Therefore, a substantial nexus of colleagues, who were linked together through a common allegiance to the ways of working advocated by Christian Schiller, were in place.29

Developments at Lincoln thereafter continued into the 1980s including the development of a small early years base of two rooms for about 15 to 20 students which was also heavily used for in-service work and by students in the evenings. In 1989, Mary worked on an existing series of first-floor classrooms, tutor rooms, stores, lavatories and corridors converted into a large primary base and in 1990 she planned the conversion of a block into tutor rooms and teaching rooms. At Bishop Grosseteste College, the primary bases were supplemented by a series of conversions of existing accommodation into, a laboratory for primary science (1981); an Arts centre (1986); a history and geography room (1989); a new building for design and technology (1989); an English studio and group rooms (1991).

When in1993, Mary and David were honoured by the University of Lincoln and awarded an honorary degree, they presented a speech returning to their theme of the relationship between education and architecture.

We have been concerned with a number of small projects, re-arrangements, extensions. And it has always been a co-operation and understanding amongst friends, with a shared understanding about basic principles. Architecture and education are not two separate subjects, but one.30

NOTES

1 DLM notes on MBC, 17 June 2005.

2 D. Gillard (2011) Education in England: A Brief History. www.educationengland.org.uk/history. C. B. Cox and A. E. Dyson (eds) (1969) Fight for Education: A Black Paper; C. B. Cox and A. E. Dyson (eds) (1969) Black Paper Two: The Crisis in Education.

3 Meanwhile Geoffrey Bantock’s Freedom and Authority in Education argued for a return to traditional values and power relationships implying a criticism of progressive practices and design. Geoffrey Bantock (1970) Freedom and Authority in Education. London. Faber and Faber.

4 UNESCO has published ‘Studies in Comparative Education’ since the beginning of the 1970s which focuses on educational issues and trends within a comparative perspective.

5 The intention of the Head Start programme was to promote school readiness by enhancing the social and cognitive development of children through the provision of educational, health, nutritional, social and other services.

6 G. Smith and T. James, ‘The Effects of Preschool Education: Some American and British Evidence’, Oxford Review of Education, 1, no. 3 (1975), pp. 223–40.

7 The results of his studies were published in Theoretical Studies Towards a Sociology of Language (1971) and Applied Studies Towards a Sociology of Language (1973).

8 E. M. Parry quoted in Schools Council Pre-School Education Project Report (1971).

9 DLM and MBC, report of meeting with Dr Parry. Institute of Education archives. SCC/180/186/500/011.

10 The Architects’ Journal, 14 February 1973.

11 Ibid. p. 10.

12 Sketch plan ‘Some Planning Ingredients’, 28 February 1972.

13 MBC notes on the needs of play spaces, file dated 1971–1973.

14 ME/L/8.

15 Mary Medd (1976) A Right to be Children: Designing for the Under-fives. London. RIBA Publications for the Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies.

16 Sherry Kaufman and Mary Bell ‘Winnetka Public School Nursery: Our journey toward becoming a Reggio inspired school.’ The Newsletter of the Winnetka Alliance for Early Childhood, Fall 2006. http://www.wpsn.org/WPSN-reggio-emilia-article.pdf.

17 R. Thornbury (1979) The Changing Urban School. London. Methuen. p. 145.

18 MBC (1976) p. 49.

19 MBC (1976) p. 27.

20 The Gittins Report was the equivalent of the Plowden Committee Report for Wales.

21 Gordon Warren went on to become director of the Design and Technology Association.

22 Design Study 2, Welsh Education Office, 1976; Education, 31 December 1976; The Architects’ Journal, 15 June 1977, pp. 117–18; Arkitekten, 12 (1980) pp. 281–5; MacLure (1983) pp. 188–9.

23 Mary and David Medd’s archive 1946–1972 … and beyond a bit, p. 8.

24 C. Schiller to DLM and MBC, 2 October 1975.

25 BL interview tape 6, 1 October 1998.

26 Schiller had founded the first course for Primary Teacher Trainees at Goldsmiths (1955) after which Len Marsh succeeded him. In 1973, Marsh took up the directorship of primary teacher training at Lincoln Bishop Grosseteste where the second primary bases were constructed.

27 BL Architects Lives Tape 6, 1 October 1998.

28 Practical Equipment Ltd, established 1931.

29 Mary also worked on primary bases at Chester College (1984); the College of St Mark and St John, Plymouth (1985); The School of Education, University of Exeter (1986).

30 DLM notes, p. 37.