International Travel and Exchange 1949–1972

Travel was always a mainstay of Mary Crowley’s life and the cross-over between professional and personal interests was never clear cut. During the 1930s and 40s, as we saw, she travelled with friends from the AA, with her family and alone. After marriage, she travelled mainly with her husband and professional partner, David, sometimes accompanied by colleagues from the Ministry. Together they made a total of 106 trips all over the world, advising on school building design and education. Rarely did Mary or David record unqualified enthusiasm for what they saw, but frequently found something to praise and were always encouraging of others’ efforts. Informal European tours and visits were important in furthering research and development on both sides of the exchanges. However there were interspersed visits of a more official character when they were invited to advise as recognized experts, given the increasing international profile of their work together. A few key examples are examined here to illustrate the way that they worked together on these occasions, and how they were perceived by others. The focus will be on some significant post-war exchanges with leading European architects and designers, and a year spent in the USA. These took place in a wider context of international exchange as a means of guaranteeing world peace in the future through UNESCO, Marshall Aid and the twinning of cities in Europe. Educationalists were a key element in these processes as were schools engaging in international exchanges.

HOLLAND, ITALY AND SWITZERLAND, 1949

In the autumn of 1949, shortly after their marriage and move to the Ministry, the Medds took a vacation in Italy and Switzerland, but as was the case with all of their many trips, the pleasures of sight seeing were mixed with purposeful visits to school sites as well as meetings with leading architects wherever and whenever opportunities arose. Mary’s travel diaries for this trip are filled with drawings of churches, measured plans and sketches of courtyards as well as street scenes. She always paid particular attention to plants and flowers and often named them in her drawings. However, Switzerland was also developing its educational plans and building new schools.

On 12 October in Zurich, Mary and David met with the City Architect Albert Heinrich Steiner, who introduced them to the newest schools and kindergarten which they visited. Steiner was especially proud to show them the recently constructed (1941–1943) Kornhausbrücke primary school which he had designed. This was on a corridor plan that nevertheless demonstrated appreciation of the scale of the child, creating an inviting and open ambience. Mary noted the playgrounds open to the public and the absence of any fence. The school has continued to be used to this day and is appreciated still for its sense of scale. On a later visit that same day, Mary recorded in her journal the detailed interior of the Dreispitz Kindergarten at Altstetten which had

three classrooms very spacious. Doors open out direct from room. Back wall cupboards complete including pull out trays. White paint, Green plants on floor. Screens. Thirty-six chairs and nine tables. Pale grey lino floor and table tops. Windows, vent sash. Roses under.

Here she made a sketch of the front entrance to the kindergarten as well as a detailed and measured floor-plan noting the unusual hexagonal shape of the two parallel pavilions.

Steiner no doubt pointed them to schools that were currently of international interest such as those featured in Alfred Roth’s book: The New School – Das Neue Schulhaus, published the following year.1 No fewer than seven of the twenty-one new schools included in Roth’s first edition were in Switzerland. These included Kornhausbrücke and also the Kappeli secondary school (1936–1937) by brothers Alfred and Heinrich Oeschger. Mary and David visited Kappeli on 12 October and while there made a detailed study of the school and its furnishings and fittings. Mary sketched a plan of the school noting its flat roofs and play areas, its three floors, and workshops on the ground floor. She paid close attention to the assembly hall, with plywood walls and ‘soft buff’ curtains. Her measured plan of one classrooms reveals an interest in the detailed finishing and she noted the tile skirting, ‘fawn’ tile cills, ‘white’, sink, ‘white’ walls, sliding cupboard doors and window, ‘blue’ surrounds. At a later date during their time spent in Zurich, the Medds dined with one of the school’s designers, the architect Heinrich Oeschger (1901–1982).

Mary’s drawings of the Kindergarten Dreispitz capture an almost identical arrangement of buildings and landscape to that achieved at both Isleworth open air school and Burleigh school mentioned above, demonstrating the direct influence of European travel that confirmed for her all that was modern, progressive and fitting in the sympathetic design of educational environments.2 From kindergarten to secondary school, their visit to Kappeli demonstrates the Medds’ engagement with international discussion emerging at this time on the question of what any school, for any age group, might be.

7.1 Mary’s sketch of street scenes, Zurich. IOE Archives ME/A/5/1

As usual, the social side was not neglected. They took lunch on separate occasions with important modernist architects practising in the city, including E. F. and Els Burkhardt, and the architect and furniture designer Max E. Haefeli (1901–1976) in his modernist house at Herrliberg which was soon to be illustrated by the journal Werk. Also on their itinerary was the Egg School, a newly built primary school currently being reviewed in the magazine Baumeister.3

SWEDEN, DENMARK AND FINLAND, 1951

Oliver Cox (1920–2010) had trained at the AA during the late 1930s (qualifying after the war) and met David Medd during the war before joining him at the Hertfordshire Architects’ department in 1946. At the AA, like Mary, Oliver had a developed a deep interest in Scandinavian art and architecture and had visited Sweden and Denmark just after qualifying to meet with architects and to study housing. Cox was a close friend of the Medds and in the summer of 1951 accompanied them on a motor tour of Sweden, Finland and Denmark. As was usual, Mary drove the car: a total of 2,147 miles.4 The architects they chose to meet with had several characteristic interests and engagements in common: they were all internationally renowned Modernists and they were all interested in making furniture as well as buildings.

Mary visited a number of schools and a wide variety of other buildings. The New Gothenburg Trade School for 900 pupils aged 15 to 17, partly under construction was viewed where she made measured drawings and commented on the ‘vast corridor spaces’. But the highlight of the trip for each of the group was their meeting with Alvar Aalto at his offices in Helsinki. There they discussed the social standing of architects and artists in Finland which was, in the opinion of Aalto, higher than in England. They also discussed the design of cars and Aalto expressed his dislike of American design – he preferred English or German. As always, Mary drew a plan of Aalto’s studio.

While in Finland, they took the opportunity to visit public buildings and town centre developments designed by Aalto, including the Helsinki Council Chamber that Mary drew and measured. At Aalto’s Finnish Engineers Club, Mary noted the décor, the curtains and the cylindrical ‘tinned’ lights perforated top and bottom. She made a small sketch of them – perhaps a model for those designed later by David at Woodside and used in subsequent projects.

In Sweden they saw the newly constructed Grondal Housing scheme where Mary sketched the internal courts, paying close attention to children’s play areas. As well as social housing, their many contacts with leading Modernist architects of the day led to evenings dining at their remarkable homes. At this time, Mary and David were lodging in London but were beginning to imagine the house they would build together. Visiting Sven Markelius (1889–1972) at his home in Kevingestrand 5, Danderyd, Stockholm (1942–1945), Mary remarked on the beauty of the house and especially its ‘simplicity of materials and plan’.5

Markelius was known for a type of Modernism that was characterized by a political, social, scientific and economic pragmatism or ‘New Empiricism’, which incorporated a softer articulation of new and traditional materials and would have appealed to these visitors’ personal and professional tastes.6

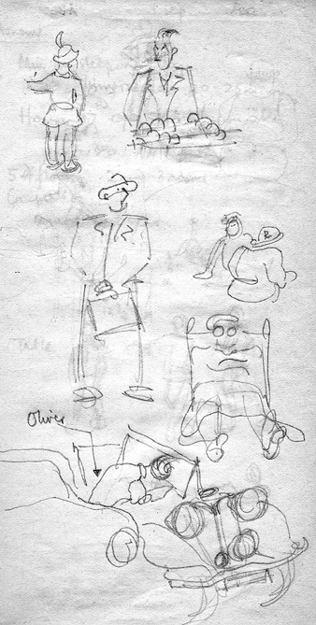

7.2 Mary’s sketch of Oliver Cox and the car used for the 1951 Scandinavian trip. IOE Archives ME/A/5/2

Leaving Sweden for Denmark, the group visited some recently finished housing by Arne Jacobson at his well-known development of Klampenborg on the coast north of Copenhagen. Mary described and sketched the staggered terraces resembling her own plan of the school she had designed at Cheshunt (1946).7 Jacobson was known for his attention to the design of every small detail of his complexes. At Klampenborg it included specifying the exact colours for the lifeguard towers, changing cabins, tickets and uniforms of the employees. This total approach to integration of design would have appealed to the visitors, who had begun to work on colour schemes for school interiors first at Hertfordshire and later at the Ministry. As well as his housing, the group visited Jacobsen’s Town Hall at Aarhus (1941).8

On the evening of 12 September, after a full day of visits, the group were entertained at the house of Morgens Lassen (1901–1987), Modernist architect and furniture designer, known after 1940 for his ‘Egyptian Table’.9 Lassen, who was inspired by Le Corbusier, ‘designed houses where both daylight shaped the rooms and where the outdoors were just as thought through as the indoors.’10

Mary was impressed by Lassens’ houses, including his own four-storey home (1936), also at Klambenborg, in reinforced concrete with wooden beams, whitewashed concrete walls, piano and chandeliers and planned with as much respect as possible for existing trees.11

POLAND, CZECHOSLOVAKIA, AND DENMARK, 1952

An international delegation of town planners and architects gathered in Poland during July 1952 to advise on post-war planning. Mary and David participated as English representatives with Max Lock and Graeme Shankland.12 First they were in Warsaw, so destroyed by military action that the whole city was to be rebuilt. They visited exhibitions and heard talks by the city planners of their 20 year programme but also took the opportunity to visit schools, including a recently constructed secondary school at Krakow. Here Mary observed a lack of any playground, good kitchens providing cooked meals, the large numbers in classes – around 40 pupils – corridors ‘only used for recreation’ and the lack of pin boards. This last feature – whether or not designers had recognized teachers’ needs to display children’s work – was often noted in her journal and pin boards became a regular feature of school interiors designed by A&BB over subsequent years.

Kindergartens and primary schools were visited as well as a factory crèche in Prague. Before returning home Mary and David stopped off at Copenhagen and visited the school at Katrinedal by Kaj Gottlob (1987–1976).

Gottlob was renowned for his school designs, the best known of which was the School-by-the-Sound (1937), Copenhagen. The Medds would have enjoyed at Gottlob’s school at Katrinedal (1933–1934) some examples of mural decoration that were his hallmark. As at the School-by-the-Sound, here he had decorated the floor of the hall – a design of the sun, while outside in the playground was a large tall sundial surrounded by a semi-circular covered bench where children could sit – a kind of open air classroom. It no doubt reflected Gottlob’s interest in open-air schooling, especially the École en Plein Air (1934) at Suresnes, France.13 Mural decorations were placed above outdoor wash basins next to the girls’ and boys’ toilets. This decorated school was part of an international trend that promoted strongly the integration of works by established artists and crafts people in the fabric of school buildings. Gottlob’s schools may have encouraged Mary and David in their own commitment to having artists work closely with architects in producing mural and sculptural pieces for new schools.14 At nearby Ungdomsgaarden (1944) in Husum, Mary and David would have been able to view the large ceiling mural by Richard Mortensen (1910–1993) completed in 1947. Here it was possible, as Mary wrote in her diary, that the youngest ‘children lie in bed and look up at the ceiling’.15 According to Mortensen, ‘You can not overestimate this importance’ that children have things to look at.16 They also visited Skovgårdsskolen (The Skovgaard School) by Hans Erling Langkilde and Ib Jensen, Østengård skole by Copenhagen City architect F. C. Lund, and Gladsaxe Stengaard Skole, by Villhelm Lauitzen, before dining with the architect Flemming Teisen (1899–1979) at his home which was greatly admired by Mary.

To visit these sites they would have needed contacts in Denmark. Many Danish architects, teachers and artists at this time were sympathetic to the Medds’ outlook. For example, at Katrinedal school, they would have met and talked with the head teacher at the time of their visit, Inger Merete Nordentoft (1903–1960). Nordentoft was a progressive educator who had joined the wartime resistance and been imprisoned. She became a member of the communist party and a member of parliament, publishing a pamphlet in 1944, ‘Opdragelse til Demokrati’ (Education to Democracy).17

HOLLAND, MARCH 1953

The Doorn Conference on 5 to 11 March 1953 was a prominent gathering of educationalists and architects interested and engaged in post-war school rebuilding or design. At about the same time, 6 to 8 March, the Tenth Conference of the Genootschap Architectura et Amicitia (architecture and friendship) was held. Mary travelled to Amsterdam with David, accompanied by Stirrat Johnson Marshall, as invited guest lecturers. At the Genootschap meeting, Mary talked about school design, the importance of architects’ relationships with clients, and argued too that schools must be ‘almost inconsequential in character, free from clichés’.18

There was some confusion as to Mary’s identity (she used her maiden name Mary Crowley) at this conference, as women in such delegations were often assumed to be merely the wives of the architects. The Dutch hosts included Van Tijan, Groosman, Bakeman and Van Eyck, who lectured on construction methods. The English architects showed their slides of schools under development in England, impressed the audiences, and a publication of the journal Forum carried their lecture in translation. There was much socializing, late-night discussions about the different merits of functionalism or humanism, and the delegation attended a film show where Night Mail (with poetry by Auden and music by Benjamin Britten) was screened. However, the highlight of the trip appears to have been a visit to Kees Boeke School at Bilthoven where they were shown around the premises by Arthur Staal, architect of the redesigned school. They were also accompanied by the head teacher, Professor W. Schermerhorn (1894–1977).

The Kees Boeke School at Bildhoven was an unusual progressive establishment designed according to a particular philosophy of education promoted by its founder, Kees Boeke.19 There were many connections between Kees Boeke’s view of children and education and that of the Medds as well as the progressive wing of HMI and Regional Education Officers in England. Boeke, like Mary, was a Quaker who together with his wife Betty – an English Quaker from the Cadbury family – was committed to the redesign of all relationships of schooling to support children’s freedom and opportunity to create their own learning paths. The original building that was designed to support a radical pedagogy went into disrepair and it was the redesign that Mary and David saw on their visit in March 1953, a result of close collaboration between the architect and educators. Their impressions were soon conveyed to the architect in a letter sent as soon as they had returned to England.

Seeing the Kees Boeke school gave us great pleasure, and to be shown around by Professor Schermerhorn, the head teacher and yourself was indeed a privilege. It must have given great pleasure in having such a close co-operation with the educators, and the result is a school that I know all progressive primary school teachers in this country would be very envious of. It is a pleasure to see a building in which the main concern has been the satisfying of the client’s requirements in the fullest sense, when so many architects, we feel, are too much concerned with satisfying their own ideas about what the building should look like, to the detriment of the user. We were specially sympathetic to your school because it seemed to spring from the same approach to design that we were trying to describe in our lectures.20

It is so rare for Mary and David to pronounce their wholehearted approval for a school and to use the term ‘progressive’ about English educationalists that this event needs to be recognized as significant. In fact, the school, in its new building, rather lost its way as a progressive establishment once Boeke had retired which points once again to the ultimate importance of the individual driving forward a view of the relationship between education and architecture that building design alone can never achieve.

The issue of the Dutch publication Forum contained lectures by the Medds including images of Aboyne Lodge at St Albans, and Templewood at Welwyn Garden City. These were set alongside an illustrated article about the new school at Bildhoven.21

DENMARK, 1954

Every summer during the first years of their marriage included some weeks in Scandinavia meeting old friends, making new contacts and sightseeing. Mary had first visited Denmark on a study tour from the AA in 1930, described above and so was familiar with the country. Connections between English and Danish architects are evidenced in the appointments diary of David Medd, for example a meeting in March 1952. Later that year, during the summer months, the Medds took a trip to the continent, first to Czechoslovakia and then to Denmark, arriving in Copenhagen on 31 July. There they stopped off, at the invitation of Flemming Teisen, and spent a couple of nights at his ‘delightful bungalow’ in the north of Copenhagen where they found further inspiration for the house they were to design for themselves in England. They also met the chief architect of the Danish Ministry of Education, Hans Henning Hansen (1916–1985) and visited schools with him on 2 August followed by supper at his flat. This was a short trip. The visit may well have encouraged both sides towards a more substantial study tour of new Danish and English schools and indeed, Hansen visited the Medds and joined a site visit to a school in development in October that same year. In the following year, 1953, we know from David’s diary that a further meeting was arranged between him and Mary with Danish architects involved in schools design. In Copenhagen, from 8 August, they met with Nils Rue and Ole Hagen. These were formative and experimental years in both countries rooted in a post-war drive to design for a new pedagogy that would recognize the needs of the individual child towards re-building civil society. The two countries were not alone in this and by the early 1950s there were several linked international initiatives to stimulate the creation of new social and educational architecture, based on progressive educational ideas and a political commitment to social welfare policies.22

A Danish research commission set up in the same year, 1954, was inspired by the A&BB Development Group of the English Ministry of Education in which the visitors were employed. Centralization and modernization of the educational landscape appeared attractive to the Danes who wished to learn how best to put research at the heart of their practice as was steadily being achieved in England. Schools for all ages of children needed to be developed, but they showed particular interest in the principles and values underlying school design for younger children as manifest in the English experience.

In May 1954 the journal Arkitekten (Fig. 4.1) featured a photo of the Medds on holiday in Italy shortly after their marriage was accompanied by an announcement that David had been formally made a committee member of the Danish Architectural Association and noted how well he was known to the Danish profession.23 It did not mention Mary in the same terms and on arrival in August it was David who was invited to join the Developmental Group at the Royal Academy in Copenhagen and made an Honorary Corresponding Member of the Danish Architectural Association.24 Together with their Danish hosts the Medds visited several newly constructed schools in the region. We know from their diaries that they initially stayed at the home of architect / planner Paul Danø, while in Copenhagen and later at the hotel Rasmussens in Faaborg on the island of Fyn (Fynen). On the morning of 9 August they heard a talk on ‘building types’ by Svend Albinus, chief architect of the Research Building Committee, and in the afternoon met with Ole Bang.25 Albinus accompanied them often on their visits and later joined the delegation that visited England in October 1954. On 12 August, the visitors recorded their ‘first observations’ in a type-written report.26 Here they remarked that the Danes should first ‘find out what sort of schools are really wanted’ and to do that they ‘must understand what are the trends in education … understand children’s needs and be able to digest the many conflicting requirements that will be voiced by the teachers.’27 They also argued for freedom for individual designers and that initiative to innovate be encouraged by thinking about the school as a whole rather than in its component parts. They asked ‘why should non-classroom teaching be inevitably restricted to a narrow conception of woodwork and cooking? If other crafts are practiced in the normal classrooms, these would have to be designed with this in mind.’28

On Monday 16 August, the agenda included a morning talk with Albinus about their impressions so far and in the afternoon they received a presentation by Ole Bang on the theme of ‘the experimental classroom’. Before the end of the year, the Danes were planning to build and put into use one or two ‘experimental and flexible’ classrooms attached to an existing school in the south of Copenhagen. The report contains a substantial critique of this project which the Danes may have thought would have impressed their visitors. However, the Medds objected strongly to the idea of experimenting within one single component of the school – that is the classroom. They argued that the project was fundamentally flawed given that, according to their view, a classroom could only be designed as part of a whole. They argued

the design of a school must be made ’from both ends’ that is from the aspect of the school as an educational whole, and from a study of individual aspects that make up the whole … After, and only after, a school design has been made and built, can individual aspects be separated for analysis and study which will contribute experience towards the next school design.29

For the English visitors, there was no question that the process of design through research that they had fashioned with colleagues first at Hertfordshire and subsequently at the Ministry of Education was applicable and advisable in Denmark, and there is no hint in this report of their taking Danish ideas and practices for adoption in England.

On 17 August they visited Skovgaards Skole, a new school built in 1952 for children of 5 to 15 years by Hans Erling Langkilde and Ib Martin Jensen. Here the English visitors found good use of an ‘exceptionally beautiful site’ and some pleasing features. There was an oak tree preserved in the outer play yard to give shade, and cherry blossom trees were planted for colour and interest. They were, however, somewhat disappointed in what they considered to be the rigidity of the educational brief and thought that the full educational potential of the school building and grounds was not yet exploited. The Danes were designing new schools with much regard to open-air play opportunities, providing some covered terraces for outside activities, but were at the time still operating a rather conventional classroom arrangement.

Mary and David visited Rungsted Skole, designed by Rasmussen on 23 August. They noted this school had been designed with the needs of children 7 to 11 in mind but this was ‘not wholly successful’ because of the plan form and reliance on standardized elements including classrooms and long corridors. The colour of classroom walls (pale grey and yellow buff) and lighting (both natural and artificial) was, they thought, unsatisfactory. They criticized the red floor that together contributed to a colour scheme that was ‘a particularly inharmonious combination of adjacent hues’.30 In contrast, at the same school they found the staff room to be ‘charming and beautifully equipped’ and Mary made drawings of its features as well as a plan to scale.31 Lighting, its quality and character, was a point of common interest for English and Danish architects that stimulated plans for further travel and exchanges. The report mentions plans for a visit to England when Morgens Volten, architect with a special brief for lighting, would meet with Dr. Hopkinson at the Building Research Station who was himself planning to visit Copenhagen in the autumn of 1954.32

7.3 Skovgaards Skole, Copenhagen, 1954. ABB/A/74/18

Kay Fisker’s Voldparken Skole, also built in1952 was visited on 27 August. Here they spoke at length to the head teacher, to other members of staff and with children, even though language differences sometimes compromised conversation. The report of their visit suggests that the head teacher had many ideas to change practice but the Medds formed the impression that he was hampered by insufficient collaboration with architects. The ‘chocolate-brown asphalte’, ‘brown chalkboards’, ‘brown perforated masonite’ ceilings and dark corridors ‘rather unpleasant in character’ were all noted. David took photographs of a ‘court’, a ‘covered way’, a ‘classroom’, an‘elevation and children’ and a ‘courtyard’ and probably made measured plans; Mary made a drawing including a side elevation and a plan of a classroom.

They visited the provincial town of Holbæk twice during their tour; once accompanied by Paul Danø and again to view a school furniture exhibition on 20 August. The exhibition, of displays by most producers of school furniture in Denmark, as well as of chalkboards, educational aids, equipment and light fittings, had been arranged by the country educational adviser Mr. Møller-Petersen. David made extensive notes which were discussed at a later date with the architect Philip Archtander (1916–1994), who was a key figure in Danish building research, and who had been on a longer stay in England in 1952.33 The Medds’ report noted some disappointment with the curatorial choices for the exhibition. David thought that ‘the visual aids and radio exhibition was over weighted, and that sanitary equipment and ironmongery could have been presented.’ Of the school furniture exhibited, they found these well-detailed and finished but ‘from the teaching point of view’ considered them to be ‘extremely restrictive … and their general character … very mechanical’. However, the visit gave rise to thoughts about the value of arranging a future exhibition, possibly in Copenhagen, which might be more selective and cover a wider field.34

On 2 September, a number of schools were visited in one day including Hillerød Skole where David took photos of the ‘open theatre’, a large and impressive ‘bathing pool’ and ‘playground’. Here they found more of interest because there was ample evidence of provision for ‘a wide variety of activities’ and they were struck by ‘the difference in character’ between various rooms. Once again they found a grey, yellow and brown colour scheme but noted more diverse colours elsewhere including the library. Mary produced a scaled drawing of the outdoor theatre.35

Even though the Danes considered the English influence to be already visible in these newly opened schools, the visitors’ assessment was nevertheless critical: ‘Our real fear is that in recent trends in school buildings we have seen in Denmark there is an increased tendency towards standardisation and regimentation of the plan’. In their opinion this should be resisted, and rather that ‘buildings for children should not be regimented and military in character but should have the same kind of charm, liveliness and spark that the children do themselves…’. The Munkegaardsskolen [Munkegaard School] by Arne Jacobsen was not yet completed but already the design was highly acclaimed whilst the Medds were somewhat disappointed in it.36 From their point of view there was no educational idea driving the design of the school. Rather it was ‘a preconceived pattern which … is a mechanical and monotonous arrangement of accommodation … likely to impose a severe educational discipline, and to have a brutal, rather than charming character …’37

They might have been a little more positive about the individual south facing classroom units each with its own ante-room and cloakroom, also used for group activities, and courtyards, each uniquely paved and affording some privacy and intimacy of atmosphere. There were certainly elements here that echoed the principles of planning found in the Hertfordshire County Council schools as well as the influential Crow Island School in Winnetka. Alfred Roth, in his 1957 edition of The New School used illustrations of Munkegaardsskolen featuring a populated ‘ante-room’ for group work with a domestic atmosphere afforded by the suspended lighting over a large table surrounded by seated children.38 But on their visit the Medds observed the classroom space to be unchallenged by teaching styles in practice, and despite some features that they approved of, overall the form supported traditional didactic teaching.

On 30 August at a meeting with the Schools Group in Copenhagen, the English architects thanked their hosts for allowing them to speak frankly and after acknowledging how much England had learned from Denmark in the past, drove home their critique of what they perceived as an unhelpful schism between the intentions of architects and educators in the country before recommending a change in the direction of English methods.39

As a return gesture, members of the Research Building Committee travelled to England in October 1954. We do not have an extensive archive of notes from this visit and nothing like the detailed documentation of school visits that characterized the Medds throughout their professional lives. The delegation consisted of representatives from the political world, from the world of education and three architects. The group included the chief architect of the Research Building Committee, Svend Albinus, Hans Henning Hansen and the architect Tyge Holm who was a personal friend of the Medds.

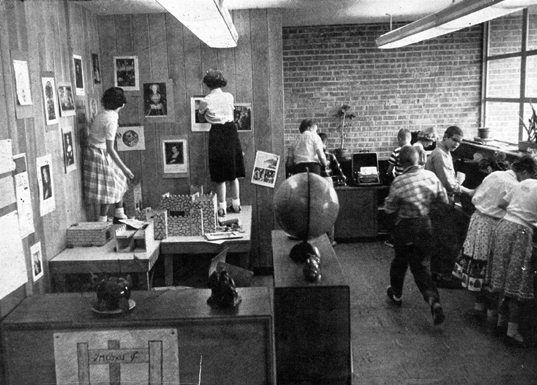

The delegation visited schools that were by this time subject to international interest including Aboyne Lodge Junior School at St. Albans, St Crispin’s Secondary School at Wokingham, and a Secondary Technical School at Worthing.40 They were guided by David Medd among others. On return to Denmark the delegation reported in particular about the integration of the nursery school into the primary school system and the important consequences it had for school architecture, making it more child orientated. The new schools they visited in Hertfordshire and Middlesex were, they observed, full of light, where children could be seen working at their own pace, and where the teacher walked around and assisted them. They saw walls of glass, doors opened out into the open air, no corridors, children’s books arranged on one wall and children’s drawing on the other. ‘A wonderful intimate atmosphere’, as Tyge Holm remarked on his return at a meeting of the research committee.41 At Aboyne Lodge Junior School the interior courtyard was appealing to the Danes as well as the indoor toilets and cloakrooms. Making comparisons between Denmark and England, Holm concluded that the schools in England were the result of holistic planning and design, whereas the Danish examples were a collection of independent spaces. Where the English visitors had found Danish school buildings rigid, the Danes found English schools ‘too loose’ and nearly invisible and impressionistic, a result of designing almost entirely ‘from the inside out’.42 But they admired the flexible use of space, integration between workshops and classrooms, and a focus on functionality and children’s development as well as creativity in solving design problems.

Apart from the 1954 trip, other lesser-known Danish architects involved in educational architecture travelled to England during the 1950s. One such case is the private firm, Johannes Folke Olsen, located at the city of Svendborg on the island of Funen which practised between 1944 and 1974. During this period the firm designed about 20 elementary schools. Olsen’s firm belonged in many respects to the vanguard of educational design in Denmark. During the 1950s they travelled to England to get ideas for group collaboration and for methods of rationalizing the construction process, but also to study school architecture in a country where more attention was paid to the needs of individual children than was the case in Denmark. Whenever possible the firm’s employees went on study tours to England. As Nicholas Bullock has pointed out, ‘by 1955 modern architecture had become established in Britain’ no more so than in the new schools emerging in the landscapes of south eastern England.43

USA, 1958–1959

In seeking the growing points of education …we found ourselves in the mountains, in the deserts, in the forests, on the plains, in the swamps, in the cities, suburbs and villages, in the pueblos and hogans, among Indian-speaking and Spanish-speaking communities and in fact in the extremes of material wealth and poverty.44

The 1950s was a period of rapid development in educational planning and school building across the United States. The Medds arrived at a very significant moment, in the midst of the panic generated by the Russia’s successful launch of Sputnik.45 The response was the National Defense Education (NDE) Act of September 1958 which significantly increased funding for Public schooling.46

The Medds wrote publicly about the impact of the NDE Act while in the USA. They talked about the fear and trepidation expressed in the legislation and warned ‘that to outsiders it seems that as state and national resources are inevitably and increasingly used for education, so must the opposing forces of freedom and control be resolved’.47

The decade also saw some of the most significant architects from continental Europe developing a presence in the country through iconic buildings, some including schools. There was also a profound recognition that education would be inevitably changed by developments in technology while talk of ‘schools for the future’, ‘learning laboratories’ and ‘the disappearance of the classroom’ inflected the debate about the form that schooling should take. For some, including the National Educational Association of the USA, improving education was a direct means of meeting the challenge of the nation’s military and economic competitors and represented ‘defence potential’ in the struggle for ‘world leadership’, a principle the Medds would have understood but would have regarded as a renegade step for the interests of children and young people.48

In 1958, David Medd was awarded a Harkness Fellowship by the Commonwealth Fund, usually requiring the holder to spend up to one year at an academic institution in the USA. David accepted the Fellowship but, seeing an opportunity for Mary and he to develop their international knowledge of developments in post-war school renewal, requested that the Ministry of Education allow Mary to accompany him. This was agreed and from the autumn of 1958, for one year, they travelled roughly clockwise, a 36,000 mile journey, starting from Cambridge, Massachusetts, having arrived by ship in New York.49 In October 1959, they returned to England from Montreal. Commencing their journey, fresh in their minds was the house they had constructed for themselves at Harmer Green, Welwyn (1954), the now operational Woodside Primary School at Amersham (1956) and the plans for a new school at Finmere, Oxfordshire. They arrived in America therefore, after almost of decade of work with the Ministry at a moment of confident authority in knowing what was possible and what was necessary when designing for education. They were hoping to see the most modern developments that united education with architecture. In their terms, this meant that architects would be working closely with teachers who were able to recognize how far institutionalized education had impoverished learning and teaching, and who could improvise with their environments. To this extent, teachers were indicating to designers how school buildings might be planned to support their educational aims.

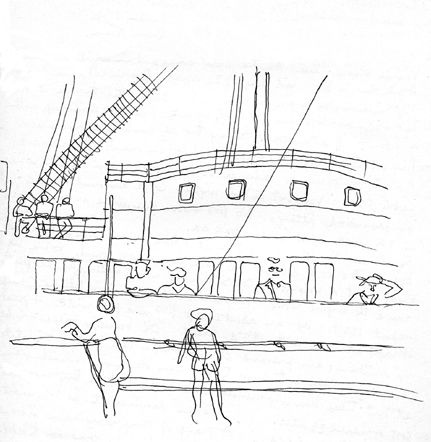

7.4 Mary’s sketch of fellow passengers aboard the Queen Mary, 1958. IOE Archives, ME/F/8

Embarking on the last day of August 1958, they were among 2,000 passengers, 8 dogs and a crew of 1,200 taking the passage from Southampton to New York on the RMS Queen Mary. There were, Mary noted, ‘quite a lot of children’ on board and ‘even a nursery’.50 Almost immediately they requested, and were granted, a tour of the engine rooms and kitchens. Travelling in some style, they found the voyage relaxing and luxurious as the food was plentiful, even ‘astonishing’, and in general they could want for nothing. The design of the cabins, however, they found a little disappointing. David would have made measured plans of the cabin as he did in every hotel room that he inhabited throughout his life. Mary found the general interior decorations ‘out of date’ with ‘no good colour anywhere’. Their personal quarters were ‘all rather Lyons Tea House and the cabins, though comfortable, not a patch on Scandinavian layout and furnishings’.51

Arriving in New York, they energetically embarked on visits and tours, enjoying the city more from a high view point than from below on the crowded sidewalks. Striking were the vibrant moving colourful designs of the advertisements that were both brash and modern but somehow appealing, ‘The sight of New York at night exceeded even the wildest flights of imagination, like some gigantic Paul Klee painting.’52 Of course, the galleries were visited and they took a stroll through Central Park, noting the playgrounds, the sailing boats and the ongoing construction of the Jose de Creeft (1900–1982) memorial to Alice in Wonderland. Mary made some delightful sketches of the park and characters passing through it. But very soon, they got down to dealing with the business in hand, arranging the best possible way of spending their time in North America.

Beginning in Manhattan, they spent half a day with the City architect, visited private architects’ offices and were shown around four New York schools. They began to negotiate how they might fulfil the requirements of the Fellowship, normally requiring an academic input at Harvard, without compromising their own desire to see and understand as much as possible of the nation’s developing education and the buildings designed to support it. Intending to travel to all parts of America, they were granted a car (a Cadillac) which Mary was to drive since David had no licence. This caused difficulties at first as since David held the Fellowship and the car was in his name. Some driving lessons were sought but finally they overcame the regulations and Mary drove throughout the whole trip.53

Between socializing and sight seeing, they were subjected to numerous talks and tours of ‘uninspiring’ public schools. But they located for themselves, through progressive contacts at home and in the USA, some pioneering private establishments, and found these to be among the most impressive and most valuable. Visiting altogether 200 schools and colleges in 40 states, including 19 from the progressive independent sector, David filled some 40 notebooks, Mary generally made sketch plans of classroom interiors and they both wrote home regularly to colleagues and to family and friends, offering us a glimpse of their experiences during this significant year. Rarely did the school superintendents that they met enquire about the English system, so eager were they to explain and describe their own school sites and systems.

The large number of schools visited included nurseries, elementary schools, high schools, schools for ‘negroes’, colleges and progressive experiments, the latter providing the closest examples of what they were seeking as ‘growing points of education’. Usually they were in the hands of district authorities who wanted to show off what they considered their best achievements, such as the integration of television labs in schools and colleges. Early on they recorded difficulty in ‘finding a technique for making such visits profitable’ and were occasionally obstructed by press photographers.54 Soon they expressed their disappointment in what they did see and hear, and were especially appalled by what they viewed as ‘the general direction away from real things, everywhere’ finding most of the high schools ‘pretty tedious’. The relationship between architecture and education had produced ‘some pretty dreary high schools with photogenic extensions and dismal education’.55 David acknowledged in a letter home to his father, ‘there is much evidence of concern and interesting experiments in school design to meet changing teaching methods, but we have yet to see actual activity in schools which matches the latter, some of which is very glib’.56 Mary’s analysis was that this was ‘mostly the fault of a constipated curriculum which is monotonously uniform in spite of lack of central control’.57 In a letter to Anthony Part, by then under-secretary and head of Schools Branch at the Ministry of Education, David indicated the need to ‘widen our field of enquiry’, as limiting the survey to public schools was inhibiting access to the ‘growing points’ in education, more likely to be seen in the newly founded progressive or experimental private schools.58 In general they were ‘finding education to be more interesting and more important than architecture – school architecture, anyway’.59

However, they were occasionally able to see, in passing, more than was intended by their hosts. ‘Trips to suburban schools have given us glimpses of the ghastly squalor around the cities’ an experience which led Mary to conclude that ‘however perfectly (American) planning schemes work – the result of selfish enterprise will lead to despair’. Although there was much talk about democracy, ‘one wonders whether much of it is a form of selfishness. Personal gain and comfort is implicit in every advertisement and even the verses we have heard recited in an elementary school.’60

The Medds found America in to be a place of many paradoxes. They were enthralled by the natural beauty and variety of the landscape and, travelling by car, they were able to reach its many beautiful parts as well as pass through its many slums and ghettos. Characteristically, Mary included in her notes a list of all the many different varieties of plants, flowers and trees that she had seen during the trip as well as the various mammals, birds and insects. They recognized and were appalled by the damage that was being done to the land and its people through what they considered to be an over-reliance on technology and the wastefulness and ignorance it generated. Mary lamented, here there were ‘vast amounts of money for huge gymnasiums in schools but not enough for “frills” such as a few trees’.61 Arriving just as Mies Van de Rohe’s Seagram building was opening in New York, according to David Medd, a ‘muted masterpiece … concerned with appearance rather than performance’, they discovered a nation in the midst of great changes, brimming with resources and rich opportunities yet shackled by fears generated by racism and McCarthyism.

Given their own recent experience of working from central government, directed to the ‘growing points of education’ by the English HMI, it is perhaps not surprising that they were somewhat perturbed by the American system. Always on the look out for the equivalent of HMI or a ‘Keir Hardy character’ as Mary described the personality of Carlton Washburne, they struggled with the antithesis of these they were subjected to. David complained about the over-reliance on private educational consultants found in America whose very existence, he thought, was ‘due to the lack of educational thinking at local levels’. Such practice left a weakness on the client’s side which ‘leaves the door wide open for architectural irrelevance’.62 Mary wrote home about the great educational debate that was raging at the time in the country. ‘Broadly they are worried about their intellectual and bright 20% of the school population (see our Grammar schools) but in attending to them they may forget about the others. They do seem to swing to such extremes in whatever they do.’63

David felt that architectural trends in the USA were over-influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright which led to an interest first in the architectural form and second in the education it was to support. They briefly met Wright at his winter quarters, Taliesin West, ‘something one has always known about and that was therefore of considerable interest to visit’ during preparations for the celebration of his 90th birthday and to their dismay, heard a few weeks later that he had died. They spent much time with fellow architects including those travelling through the USA like themselves. Several times they met with the Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen who, with his wife, was also travelling through America and dined with old friends, including Max Lock who had, one year earlier, taken up a temporary fellowship at Harvard.64 They met the daughter of Christian Schiller, who was living and working there and they were guided to progressive establishments by Ena Curry who had settled in California after the dissolution of her marriage to Bill Curry. Their ‘contacts grew as (they) ploughed through the country from motel to motel’.65

The ‘Ena contacts’ took them to the Rocky Mountain School in Colorado, founded in 1953, and they enjoyed a ‘pandomonic’ evening’s conversation with the founders, John and Anne Holden, originally teachers at the Putney school in Vermont.66 They discussed the recent history of progressive education in the USA and the delicate balances that needed to be struck in order for the public not to be deterred by its excesses. John Holden, like the Medds, would have preferred progressive practices to be incorporated into public schooling. ‘Why not an eight hour day for public schools so that pastoral work could be included?’67 They discovered at Rocky Mountain, in relative wilderness, a fascinating project where the pupils were constructing their own buildings and where there was a great emphasis on simplicity and respecting nature.68 The Holdens introduced the Medds to the work of Ed Yeomans whose book, Shackled Youth they read aloud to each other as they travelled. Yeomans had founded an independent progressive school in Ojai, California in 1911 based on the principles of experiential learning and understanding of nature.69 Like many of his generation and social class, Yeomans had found his own education to have been dull and stifling, and wanted to establish a school that would emphasize experiential learning and a love for the outdoors. He envisioned a place where music, art, and construction would be equally valued alongside more traditional subjects. Such a school was what the Medds thought should be possible to design given the interest in the UK among educational leaders such as Alec Clegg for such a balanced curriculum.

BUILDINGS AS ‘BACKGROUNDS TO THE SCHOOL’S ACTIVITIES’

Yeomans’ son, Ed Yeomans (Junior), was at the time principal of Shady Hill School in Cambridge Massachusetts which the Medds visited early on in their journey.70 The school for 490 pupils, grades 1–9, had been founded by a group of parents in 1915 and, in modifying some of its principles, had, according to David, become more generally acceptable without loss of some of the values its founders had stood for. Shady Hill was the rare kind of school that Mary and David were looking for. Here was ‘an excellent example of a building or buildings following the dictates of an attitude towards education’.71 In the buildings erected in 1920 they found the appropriate understanding of ‘variety’ they were searching for. Each grade group had a building distinctively different from the next, being planned for the specific age group and they discussed the absence of corridors, a feature mentioned by Yeomans.

First of all, it was decided that the architectural character should be modest and unimposing. Simple materials were chosen and interiors were not to be final and polished architectural compositions. They were to be backgrounds for the school’s activities.72

Yeomans informed Mary and David that over recent years, the parents of pupils at Shady Hill had put enormous pressure on their children to get into college. To the extent that the school had been forced to ‘protect’ children from their own parents. The children’s home life was becoming fast paced and therefore the school needed to balance this with an approach that emphasized ‘simplicity, stability and a certain amount of routine’.73 Mary drew a plan of several of the rooms, noting the detail of furniture and furnishings.

When opportunity arose, they were hosted at the homes of architects and, as in their tour of Denmark four years earlier, were drawn to comment on the form and style of the homes that these had built for themselves. Mary wrote home that such experiences had given them plenty of ideas about how they might improve their own new dwelling at Harmer Green. They enjoyed four nights at the home of architect John Henry Scarff in Baltimore and were able to stay for a lengthy period at the Chicago home of Larry B. Perkins, of Perkins, Wheeler and Will, by that time known as one of the more progressive architectural practices in the USA.74 Spending a full five days at the New York offices of Perkins, Wheeler and Will, they met Willard Walcott Beatty (1891–1961), an eminent architect and educationalist advising the firm and an ex-colleague of Carlton Washburne. Beatty was a progressive educator and an important figure in the development of federal Native American education policy during this time.75 In Texas, where they found public schools more to their favour, as will be discussed below, the architect William Caudill offered hospitality, valuable help and introductions.76

As they travelled from state to state, the Medds met with architects responsible for some of the most noted innovative school plans of the decade. In Schoolhouse, edited by Walter McQuade, the most popularly admired American schools included Hillsdale High School, San Mateo, California, with an innovative and flexible loft plan, prophetic of things to come’.77 But the Medds found the landscape of California more attractive than the schools as they travelled ‘from wonder to despair’ and Hillsdale left David with a clear argument to make against an American tendency towards uniformity of character offering an unsatisfactory ‘flexibility of the wrong kind- mechanical rather than … “built-in” flexibility, which is better translated as variety’.78 This provoked him to make a plea:

How about a school run by educators or teachers and not by administrators? How about libraries run by teachers and not by librarians? How about the great outdoors instead of gyms? How about abandoning text books? How about teaching about the sources of Western Civilization rather than its white projection (?) in the States of Colorado or California? How about accepting the fact that the High School has created Americans who practice loyalty to higher authority? How about the High Schools learning from the better elementary schools …if each person is to go at the optimum pace, groups will be various in size and the standard classroom disappears? How about running a high school on the basis of trust and self sufficiency rather than suspicion and imposed discipline? Are not these the sort of questions upon which the architectural solutions follow? Otherwise, the cart is before the horse and the result – a Californian school’.79

They were taken to ‘ghastly schools in New Mexico and Arizona’ finding some relief in the latter State at an experimental school, Verde Valley in Sedona, founded in 1946 by Hamilton Warren and opened in 1948 by ’Ham’ and his wife ‘Babs’, ‘a very good place’ according to Mary.80

In North Carolina, they were able to visit schools for ‘negroes’ and were faced with the reality of racial segregation and what they considered a deeply unjust distribution of resources.81 They avoided getting too embroiled in distressing conversations around segregation but their letters home betray awareness of the stirring of a strong and growing movement against it. ‘The movement of the coloured people has great weight behind it, a wave which may have backward and forward drifts of foam, but a clear direction in the end. Equality in two camps is not the final equality.’82 Mary observed examples of the effects of racial segregation. ‘Coloured children can’t afford to go on school trips and parents can’t afford to support them’, and described one school for negroes where ‘nearly 900 little black children’ occupied half the floor area enjoyed by a nearby County Day school for white children which had only half as many pupils.83 She agreed with educators in the district of Durham that ‘formal education is only a part of education’ and that the problem was cultural, rooted in poverty, and existed outside of the school walls as well as within them.84

In New Orleans, they were entranced by the city but walked out to some of the ‘worst of the slum areas’. This was typical of their travels: they were anxious, and sought every opportunity, to go beyond their remit and especially see more than their official hosts were keen to show them.85

By the spring of 1959, Mary was able to reflect on an emergent summary of knowledge gained from their survey, having witnessed the best and the worst of the range of possibilities in American schooling. In a letter to Pat Tindale, carrying out the Finmere project at home, she wrote,

I suppose we’ve been inside 80–85 schools by now of one kind and another ranging from a 75’ long monstrosity entirely encased in concrete fretwork, with central corridor, in New Orleans and another ditto in Hobbs Texas with no windows at all, to Caudill schools in Andrews (also Texas) which set standards of achievement altogether for us both in the education and design of schools … we’ve talked with schools superintendents and teachers black and white and in large quantities, with architects and janitors, with men at gas stations and with ghastly ladies who have too much money and insist on showing you the house they designed. We’ve slept in innumerable motels; in inns and friends houses and colleges; once nearly nowhere when we thought we’d been invited and hadn’t been; in a ‘guest house’ in New Orleans with rooms 16’ high and steam radiators which started off machine gun drill at 2am.86

Always in mind was a comparison between what had already been achieved in England’s new primary schools and the elementary school counterparts in the USA. Mary thought that the American reliance on artificial lighting was heading in the wrong direction and that ‘the necessity of skilful daylight designs in our (English) schools has produced more graceful interiors’.87

Some of the progressive educationalists in early twentieth century America were known by reputation and their works cherished by Mary’s father who passed these on to his daughter. The area of the USA most identified with progressive ideas in education and the arts was that surrounding Lake Michigan with Winnetka, north of Chicago to the west of the lake and the Cranbrook Academy schools at Michigan to the east. In architecture and design, a convergence of aims and experiences here tied Scandinavia to the aspirations of the Middle West of the USA through a powerful interest in that region in the arts and crafts. The Art Institute of Chicago had its counterpoint in the Polytechnic Institute of Helsinki, illustrating a creative tension between the rural past and the urban future.88

The Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan is emblematic in the history of education and architecture at this time. The Cranbrook Educational Community was originally conceived by newspaper proprietor and founder of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts, George Gough Booth (1864–1949) as ‘a great big barn where a lot of artists got together and shared their talents. One would be reading in one corner, and one would be doing drawing and sculpting and so forth.’ Rather than a school of arts and crafts on the Bauhaus model, ‘there’d be groups and they’d all be working together and help each other’.89 Booth, though not an educationist was, like Mary’s father, convinced of the potential for informal learning in a context planned for health, well-being and efficiency, through appreciation of the arts and crafts. Booth had, like Carl Milles, experienced a sojourn in Rome in the 1920s and was there inspired by the classical arts, but was also drawn to European Modernism. He and his wife Ellen had their own home at Cranbrook gradually extended and developed into a community resource to celebrate and encourage education in arts and crafts. Shortly after his arrival in America, Booth met the architect Eliel Saarinen and invited him to become architect in residence at his newly-established community. Saarinen agreed and was invited by Booth to build the five institutes of the educational community: the science institute, the academy of arts, the boys’ school, the girls’ school and the kindergarten. Artists and designers attracted to Cranbrook included ceramicist Lillian Swann who married Saarinen’s son Eero (1910–1961), and the furniture designers Charles and Ray Eames.

Saarinen’s theory of design drew on the social function of context. His wife Lillian recalled his emphasis on ‘big grand things’. ‘If you’re going to do an ashtray, you have to know what table it’s going to be on. And if you’re going to do a room, you have to know what kind of house it’s going to be in. You have to think of the next largest thing to what you’re commissioned to do.’90 This integral approach to design considered every detail including furniture, fittings and decoration and was in keeping with the Medds’ philosophy and practice.

It is no surprise, then, that Mary and David visited Cranbrook Boys’ School, Bloomfield Hills, while in the Detroit area and met with the head teacher Harry D. Hoey (1904–1995). Hoey had taught English at Cranbrook since 1928 and served as headmaster from 1950 to 1964. He and his wife Nerissa lived in the headmaster’s house on the school campus and was renowned for his hospitality to guests, visitors and even on occasions school pupils.91

At Cranbrook, designed by Eliel Saarinen in 1925, Mary found her ideal in the sense that here sculpture and architecture were combined to humanize and enrich the experience of living and learning. She wrote home of her view of his Academy for the Arts building ‘Saarinen and Scandinavia in the middle of the USA‘ but she regarded the ‘vista’ as ‘spoilt by the large water tower just off axis’.92 Otherwise described as ‘a connectedness of parts, a kind of sculptural wholeness that Saarinen used the word “organic” to describe’.93 With sculpture and fountains set in the decorated courtyards, Mary was delighted to see Milles’s ‘Europa’, ‘Jonah and the Whale’ and the ‘circular fountain of youth’ which would certainly have reminded her of Milles’ garden at Stockholm. Floors inside and out were given as much detailed attention as walls here and this was the case in other schools designed by Saarinen where courtyards and entrances were decorated with paving and brickwork in grid like forms in order to frame the fountains and sculptures that form centrepieces, ‘a synthesis of architecture, landscape design and sculpture’.94 This extraordinarily rich decorated environment was the product of a close relationship between architect and artist working freely within an educational project that recognized the value of cross-disciplinary collaboration. While there, Mary drew a plan of a classroom while David made a measured plan of the more recently constructed arts and crafts room noting work with ‘metal, wood, a pottery, a forge, painting and sculpture’.95 This was where boys were able to work by themselves at their hobbies after school time. It included a workshop in automotive equipment.

Another project of Eliel Saarinen’s and generally recognized as the most influential public elementary school building in the USA at this time was Crow Island School. The school was designed in collaboration with Eliel and Eero Saarinen by the young Chicago firm of architects, Perkins, Wheeler and Will, and completed in September 1940. The origins of Crow Island as a progressive public school can be traced back to 1919, when Carleton Washburne, who had visited Bedales on his tour of the best progressive schools in Europe, first became superintendent at Winnetka, Illinois. Washburne’s philosophical orientation towards the interests of the individual child guided not only his support for individualized instruction, but also his belief that children’s native curiosity should be harnessed through first hand experience. He accordingly promoted the use of art, music, discussion, play, field trips, and various kinds of group-work as a means of engaging children’s creativity while drawing them into learning about the world outside of school. Crow Island was the result of bringing together some of the most progressive educational ideas of the time clearly articulated with modern architectural interpretations of school.

7.5 Arts and Crafts workshop, Cranbrook School, USA. Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, USA

Washburne was by all accounts a large figure and charismatic man who liked to get out into schools and get to know teachers and children directly, ‘often sitting on a kindergartener’s chair in the front row at assemblies, his knees up to his chin’.96 He wanted the same direct approach to understanding education from the architects he employed.

Crow Island was carefully planned as a school that signalled a new understanding of how to meet the child’s developmental needs. It seems odd at first to imagine that the architect who designed the monumental and grand central railway station at Helsinki might be employed to design a child-like environment such as the modest single storey elementary school that was Crow Island. But when in 1937 the Winnetka School Board were seeking an architect to design Washburne’s ideal elementary school, they took a trip to Detroit to see the schools at Cranbrook. Cranbrook was admired as: ‘a complex of brick buildings set gently into the land that gained a warm feel from pillars, archways, chimneys, and towers as well as arts-and-crafts interiors’.97 The Board was especially impressed with Eliel’s school for girls. One member reportedly told the architect Larry Perkins, ’the dining hall affects me the same way a fully complete orgasm does’.98

Initially Perkins had had to convince Washburne of his own firm’s suitability to build his ‘dream school’, concerned as Washburne was that an inexperienced practice could not rise to the challenge, and believing that only a renowned architect could achieve his ambition. However Perkins managed to strike a deal with Eliel Saarinen, already well known and greatly admired for his several buildings at Cranbrook. Perkins pledged to study existing Winnetka schools considered to be leading in progressive pedagogy, to read everything Washburne had written, and to consult with teachers, principals and school custodians.99 He did this for one year ‘sitting in classrooms literally for weeks at a time and telling stories to the kids in return for watching and plotting their actions’ and came up with six planning principles. These were the provision for ‘individual academics’, the traditional classroom with the child sitting at a desk; group academics; individual activity; group activity; toilet arrangements and clothes management.100

Washburne’s idealized philosophy and insistence that this school should prove a model of excellence for the nation, generated the energy and commitment required for the collaboration to succeed. Perkins spent three or four months in schools closely observing teachers and talking with children, sketching and planning.

The art teacher said, ’let’s make patterns of the building’ Out of that grew a model of an L shaped classroom made by John Boyce. It was carried around Horace Mann school where the teachers, children and architects all played with it. It went to PTA and Board meetings and was shown to outside professionals where more people responded to it.101

He credited the overall plan as heavily dependent on Philip Will, but the team as a whole came up with the L-shaped classrooms.102 Perkins made a table-size model of a classroom, with miniature furniture, and placed it in the corridor of nearby Horace Mann School to encourage criticism and suggestions. There was no lack of these, and the model furniture was rearranged by teachers while engaging in discussion about their imagined space.103 According to Washburne, ‘The profusion of ideas flowing from our highly articulate staff nearly drove the architects “crazy”’.104 Teachers and children took part in discussing the detailed arrangements but the essential principle that each class group should have at hand all of its basic needs, as in a small home, was adhered to throughout.

A single-storey building designed to fit the child was achieved through consistent attention to scale whereby, for example, all light switches were positioned at a child’s reach, door handles similarly positioned and in the auditorium chairs graduated in size, small at the front, were available. Ceiling heights were lowered from the school district’s standard 12 feet to 9. Windows positioned not only to give interior light but also views out to the woods beyond the school boundary. Recognizing a small child’s tendency to hug the wall as they passed through school passageways, the warm tone of the internal brickwork was exposed, but at the level of a child’s waist ran smooth wooden rails, designed by Eliel Saarinen, the length of the expansive linking corridors. Details such as immediate access to an outdoor court for each class were drawn from ideas circulating at the time closely related to the open air school movement in Europe. Fourteen classrooms were designed to allow for the flexibility and activity demanded by Washburne’s educational philosophy that was a legacy of John Dewey’s Laboratory school. Children were understood to need both the security of their home base and the freedom to follow their own special interests, so for one hour each week Winnetka elementary schools were regrouped, ‘not by grades but by interests, the child leaving his (or her) grade room and going to the room in which the others who have an interest in common with his are gathered’.105 It was such regrouping that Perkins had observed, and through such had come to realize the final design of Crow Island. While the Director of Activities, Frances Presler had resisted a school mural, ‘lest it designate too definite form of creation thereby inhibiting instead of encouraging child expression’, Eero’s wife, Lillian Swann was invited to provided glazed ceramic tiles for the exterior. Each of the 23 small animal forms were placed not as mere decoration but were integrated in the construction process. As she recalled, ’Eliel designated that he wanted a sculpture here and there (and) the brick-man would leave a hole for me. So I’d go home and make something to fit into that hole … like a square sort of box and then on top of it I’d have my animal. . and each courtyard had a sculpture and I did purposely come down low enough for children to touch them. And I tried to choose subjects that were being studied by those children.’106 The whole Saarinen family was involved: Loa had a weaving studio at Cranbrook where she made curtains for the school.107 Furniture and fittings for Crow Island were designed by Charles Eames in collaboration with Perkins and Eero Saarinen.108 Eero designed children’s chairs and benches and with Perkins the school’s desks and tables. Later, Eero reflected on the process: ‘We were trying to find the complete functionalism of this intangible problem of human children and how they should be schooled … The enthusiasm of the principle of functionalism was applied to the working out of the programme.’109 Finally, and most importantly, Washburne insisted that those who taught at Crow Island had the best qualifications and preferred intellectuals who could understand his philosophy and develop it in practice. The school gained international fame through articles published in the architectural press as well as through the inclusion of large photographs in an exhibition ‘The New Architecture in the United States’ prepared by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.110

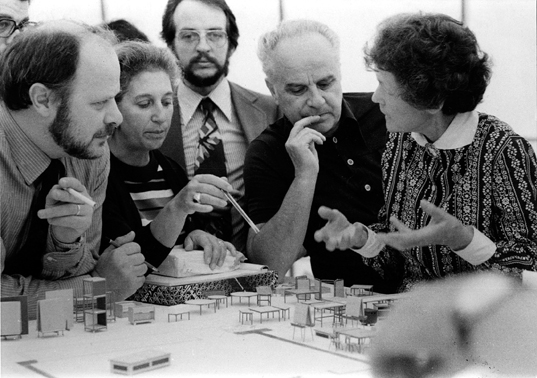

7.6 Mary with David Medd discussing the positioning of school furniture with an international group of architects at Monza, Italy, 1975. IOE Archives, Medd Collection

7.7 Plan of classroom, Crow Island School. Alfred Roth (1957)

What is remarkable is that the design process carried out at Crow Island was followed almost exactly by Mary Crowley and David Medd in later decades. Their attention to scale in provision of fittings within the reach of small children and their concern with the quality and design of furniture and fittings is very similar. We know that they met with Larry Perkins during their year long stay in the USA and they may have talked over the value of close observation, designing for comfort and function and working with miniature furniture in encouraging teachers to think spaciously. In the following decades, through the Medds relationship with Pells Furniture Manufacturers a complete set of miniature school furniture had been made and this was used in teacher training and in work with architects at home and abroad.

Shortly before visiting Crow Island, Mary was able to meet Carlton Washburne at his family summer home on the shores of Lake Michigan.111 Their world views were similar and they would have had much to talk about: Washburne had become a Quaker during the 1930s. By this time, his ‘ideal’ Crow Island School had achieved an international status as the prototype of modern elementary school building in the USA.

Mary and David visited Crow Island School on 19 June 1959 and as ever, they were as much concerned to understand and see the approaches taken to teaching and learning as with any recent alterations to the building. They met with Marion Carswell who had been principal at Hubbard Woods school during the planning years and head teacher at Crow Island between 1951 and 1955 and was now an education advisor to the Board of Education. She would have explained to the Medds how prior to the revolution in design initiated by Washburne,

the children pushed upon us what we didn’t have in that formal classroom set up. They wanted bigger classrooms, a workroom, toilets for each classroom so they didn’t have to stand in line, and running water for their art projects. The teachers had wanted flexible spaces, furniture, bay windows.112

However, she regretted some of the changes that had taken place since, ‘giving in to public opinion trends’ and a shift towards more fixed academic boundaries between the subjects that originally had been merged.113 Discussions held with the staff, very few of whom had been part of the original school, revealed a shift away from some of the more progressive practices of the past and a retreat to emphasis on the 3 ‘Rs’, imposition of discipline, more attention to ‘gifted’ students. The suggested reasons for this shift included ‘fear of Russia’ and the general climate of the Cold War.114 But there had also been a growing unease with Washburne’s methods which many teachers and parents thought had held children back. Donald Rumsfeldt, US Defence secretary under George W. Bush, attended Crow Island for a short time as a child and recalled the relatively slow progress he had made before moving to other schools. Some considered the curriculum too mechanistic and limiting to children.115

In the original design, the main space in each L-shaped room contained blackboards and single transportable desks, enabling easy arrangement for conventional teaching and group-work, while the workshop section provided access to materials and space for the practical work which was regarded as an essential component of the curriculum.116 All that was viewed with great respect by the Medds who had become familiar with this iconic school building from descriptions of it in the architectural press, but they were particularly interested in recent extension work carried out in 1955 to meet the extra demand created by a post-war baby boom. They were generally impressed with what they encountered. ‘In the extensions to the Crow Island School, what might have been a normal corridor is enlarged into a most generous ”foyer”’ or ”activities area” (containing) a large fireplace, easy chairs and cushioned wall seating, a sink and cooker.’117 These facilities were to encourage community use as well as to provide a domestic homely character to the environment.

7.8 Work area, part of each classroom at Crow Island School, 1955. The image was published in Nation’s Schools magazine, published by Dodge. Photograph Coster, Chicago Art Institute collection

The new wing used the same common brick and ponderosa pine as in the original building. Mary often remarked, as we have noticed before, on brickwork and especially the effect of tone and pattern. Here she was able to see brickwork at its best under the guidance of Eliel Saarinen. A grid pattern on the tower resembled the patterned terraces at Carl Milles garden in Stockholm and was present in Saarinen’s buildings at Cranbrook and elsewhere.118 Saarinen was fond of creating a raised map of his building out of a brick profile and installed one here. Internally the exposed rose coloured brickwork, chosen by Eero, presented a warm tone, auditorium walls striped with cinderblock and stairwells framed with thick brick pillars, their exposed edges curved and rounded as if brushed by thousands upon thousands of children’s bodies. Vertical darker brick was used at floor level for practical and aesthetic reasons realizing the tendency of children to kick against the corridor walls.

A mixture of redwood was used for external parts, and inside ponderosa pine treated with wax. Mary noted later in a hand written copy of an article about the school, published in 1941, that Crow Island demonstrated, ‘you can build specific spirit with landscape, brick, wood, metal, glass and textile; with shapes and masses and strips of colour … a place of joy in living’.119

They also found at Crow Island a building and equipment scaled to the pupils’ physical requirements; detailed attention to display and working surfaces; practical work areas in classrooms; domestic lavatories for each class; modern standards of heating, lighting and ventilation and outdoor teaching facilities. They only thing they found to disappoint was the ‘”tidying up” of a small ravine and stream that at one time had crossed the site’.120 Finmere Village School, completed shortly after the Medds’ return to England achieved a similar spirit and was furnished in the same spirit with a dedicated space for resting (including a built in bed) and contemplation (with a built-in fireplace).

The intricacies of design at Crow Island were based on a progressive understanding of education in stark contrast with other schools that the Medds saw in the United States where, ‘the relatively empty and formal scene encountered in some classrooms, compared with the wide range of activity and richness and the paraphernalia in others suggests that space and small numbers – both admirable in themselves – are not the only key to good teaching.’121

It was rare to find more examples of public schools designed with a progressive approach to education as a starting point and where, as at Crow Island, educators and architects had collaborated and developed a common vocabulary. As David explained, ‘because we believe in diversity rather than conformity, we are trying to seek out buildings that express an educational ethos rather than an architectural preconception’.122 They were to find this in some of the public schools recently designed in Texas.

One of the architects whose commitment to school work most impressed the Medds was William W. Caudill (1914–1983). Caudill was also an academic and the author or coauthor of 12 books, the most influential of which were Space for Teaching (1941) and Architecture by Team (1971) which argued for interdisciplinary planning in accordance with the proposed function of the building. His major reference work, Toward Better School Design (1954) focused on flexible use planning, such as the implementation of movable classroom partitions, storage space, and indoor-outdoor connections. Progressive and deeply interested in education, Caudill led a practice with a commitment (familiar to the Medds) to challenge conventions in school design so that activities associated with ’learning by doing’ which had not yet been properly accommodated in architectural terms, might be facilitated, and so that schools could adequately house the ’different kind of curriculum’ entailed by the activity-based approach.123 Mary wrote home,