17

JUAN O’GORMAN AND THE GENESIS AND OVERCOMING OF FUNCTIONALISM IN MEXICAN MODERN ARCHITECTURE

Juan Manuel Heredia

Under the title La Génesis y Superación del Funcionalismo en la Arquitectura, the first published version of Alberto Pérez-Gómez’s seminal book Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science appeared in Mexico in 1980.1 Devoid of Husserlian allusions, Pérez-Gómez’s Spanish title gave no hint of his phenomenological emphasis but was more suited to the Mexican audience. The term functionalism had been at the center of debate in Mexico ever since a group of “radical functionalist” architects initiated that country’s modern movement in the late 1920s. Denying any relevance to art, aesthetics, or “spiritual necessities,” these architects gained their reputation thanks to their uncompromising attitude and the strikingly austere and utilitarian character of their buildings. Conceiving architecture as “engineering of buildings,” their work was also inextricably linked to the creation of the Escuela Superior de Ingeniería y Arquitectura (ESIA) of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN), Pérez-Gómez’s alma mater and the sponsor of his book. Founded in 1936 inspired by the example of the École Polytechnique in Paris, the IPN embodied the positivistic legacy targeted by Pérez-Gómez and embraced in Mexico at many levels of culture since the end of the nineteenth century. Founded four years earlier but immediately incorporated into the IPN, the ESIA advocated the teaching and dissemination of a “technical architecture” in service of post-Revolutionary Mexico. In retrospect, Pérez-Gómez’s book constituted an indirect criticism of his school, of Mexican functionalism, and of Mexican modern architecture in general.

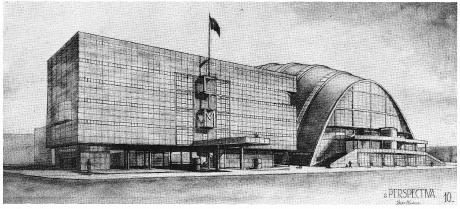

Four decades before the book’s publication, however, an architect also affiliated to the ESIA attempted in Mexico an earlier criticism of functionalism. Indeed, shortly after the school’s opening, its founder and the most radical of Mexican “radicals,” Juan O’Gorman, retreated from his views that regarded functionalism as a vehicle for social emancipation and began considering it an instrument of capitalistic accumulation. O’Gorman’s repentance would not only lead into his formal retirement from the profession but, fifteen years later, to his dual architectural swan song: the mosaic-clad library of the University of Mexico and his surrealistic cave/house on the outskirts of Mexico City. His criticism of functionalism and the implicit and explicit appeals to corporeality and meaning contained in it show many parallels to Pérez-Gómez’s academic work. The deterministic character of his thinking that added to his conflicted personality, however, led him into theoretical conundrums that greatly differed from the latter’s more rigorous and fertile theorizing. Nevertheless O’Gorman’s career as an architect developed with certain autonomy from his theories, showing throughout the years a level of maturation that went unsuspected to the architect himself (Figure 17.1). This essay traces O’Gorman’s architecture and his embrace and criticism of functionalism, acknowledging his importance in the history of modern architecture and in doing so helping to situate the legacy of his unsuspected successor.

Born in Mexico City in 1905, Juan O’Gorman was a central figure of Mexico’s post-revolutionary culture.2 A descendent of British diplomats and Mexican Independence fighters he grew up in a sophisticated environment cultivating a strong nationalistic spirit and a cosmopolitan taste for the humanities, the natural sciences and the arts. Encouraged to pursue his artistic sensibilities through painting, O’Gorman eventually joined the ranks of the socialist artists surrounding Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Instead of painting, however, he decided to study architecture and enrolled in 1922 in the school of architecture of the National University, then the only school of architecture in the country. O’Gorman studied during a transitional period when most of the school’s faculty adhered to an eclectic pedagogy legacy of more than a century of academic instruction in Mexico, but when the combined spirit of renewal of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) and the Neues Bauen was strongly felt.3 As a student O’Gorman was in fact pivotal in renovating the school of architecture, mobilizing his classmates to request the support and inclusion of faculty of a more modern persuasion. From these teachers he inherited a structural-rationalist view of building, a proficient knowledge of concrete construction, and a preference for stripping down surfaces from inessentials.4 His most influential teacher, Guillermo Zárraga, transmitted to him a patriotic spirit and an idea of architecture as service for the provision of shelter for the people, yet also encouraging him to consult international periodicals for learning and inspiration. An alleged “anti-Vignolist,” Zárraga was also probably who first introduced him to the work of Le Corbusier.

Figure 17.1 Juan O’Gorman, CTM Union building project, Mexico City, 1936

In a series of domestic commissions dating from 1929 to 1935 (and that famously included the twin houses for his friends Kahlo and Rivera), O’Gorman demonstrated a precocious assimilation of Le Corbusier’s formal vocabulary (Figure 17.2). More interested in external details and the exposure of electrical, mechanical, and tectonic features (wiring, plumbing, concrete frames and surfaces etc.), however, his projects resulted in largely iconographic exercises bent on expressing a possible modernity for Mexico. Notoriously absent were the formal strategies that could have generated the spatial complexity and sequences that characterized Le Corbusier’s architecture. In aligning the partitions to the structural frame, O’Gorman in fact created highly compartmentalized interiors closer to the idea of existenzminimum than to a Corbusian “promenade.” Moreover, their proportions were not the result of a careful study of human uses but of a building module (the three-meter spacing of concrete reinforcement for load bearing walls) subdivided or multiplied in consideration of a “function” abstractly and univocally conceived. Along with these modernist features the houses also incorporated a series of “vernacular” motifs: vibrant colors, clay bricks, dry-stone terraces, and cactus fences, etc. Presumably introduced for economic reasons, these elements actually reinforced the houses’ expressive and pictorial character. At any rate, O’Gorman never rationalized his houses in regional terms but instead referred to them as the first “functionalist” houses in Mexico.

Figure 17.2 Juan O’Gorman, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera house-studios, Mexico City, 1931

By functionalism O’Gorman meant when architecture’s form “completely derived from its utilitarian function.”5 Elsewhere he defined functional architecture as that “only useful for the mechanical aspects of life,” and that “exclusively satisfied the need for shelter.”6 These definitions were in turn based on the “theoretical principle” of “minimum expenditure for maximum efficiency,” and were thus justified in view of the need to act with the outmost economy, objectivity and expediency in Mexico. Circularity of argumentation apart, O’Gorman’s definitions represented the most deterministic notions of function in those years.7 On the one hand, they exhibited a dualistic conception of life that sharply separated corporeal (“mechanical”) from intellectual or spiritual existence. On the other hand, they were oblivious of the codetermining relation between built form and human action.8 More importantly, O’Gorman’s idea of function disregarded the metaphorical meaning that the term had historically possessed since its adoption by architects in the nineteenth century.9 As it has been recently argued, this meaning was still present in twentieth century functionalism, and was present in O’Gorman’s work.10

Indeed, despite his claims O’Gorman’s buildings were conceived as metaphorical, not literal, embodiments of function. Both their modernistic and “traditional” elements were more a matter of display than of actual operation. Admittedly these elements performed, to different degrees of success, in the ways prescribed by the architect. Yet they did it also, but stronger, in the theatrical sense of the term. A collection of pictorial and didactic motifs, the houses lacked the internal and external articulations that could elevate them to a “higher” narrative or poetic level.11 Moreover, O’Gorman’s modular design was exacerbated by his strong interest on spatial economy. This produced very rigid arrangements that made the owners alter them, paradoxically questioning the architect’s claims. This was perhaps more evident in the house for his friend Kahlo: a beautiful object but a rather oppressive setting that obliged its disabled owner to flee into the more spacious adobe of her youth.

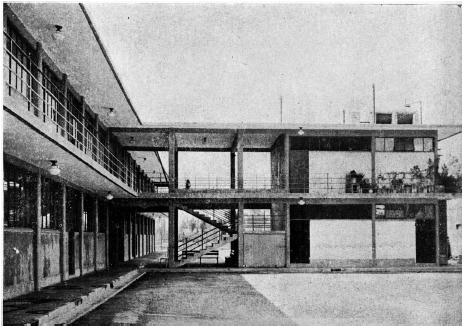

Rivera’s patronage of O’Gorman, however, unexpectedly led in 1932 to the architect’s appointment as head of the Department of School Construction of Mexico’s Ministry of Education. Far from gratuitous his appointment obeyed the government’s interest in his theories, and its dissatisfaction with the way public schools had been built until that time, not keeping pace with an increasing demand or with the project for establishing a socialist education in Mexico.12 O’Gorman’s first initiative was the construction and renovation of over fifty elementary schools with an overall budget of one million pesos, the sum normally destined for the construction of a single school designed in the standard eclectic fashion. Although built with the same construction technique, modular logic, and exposed elements as his houses, O’Gorman’s “functionalist” schools were less formally indulgent and designed in real view of economy and potential growth (Figure 17.3). Yet they transpired a similar didactic spirit, which given their programmatic character, was perhaps more appropriate. Linearly and symmetrically arranged, they had a regimented character only alleviated by the strategic detachment of columns in vestibules. O’Gorman also painted the buildings in different colors to make them more agreeable to the people who would inhabit them. More graphically he painted, or rather wrote, the phrase Escuela Primaria (“elementary school”) on selected walls on the outside to make them more recognizable. Giving continuity to the work initiated a decade earlier by Rivera, O’Gorman also invited a group of muralists to decorate the vestibules with frescoes displaying political and pedagogical themes. Despite their realistic style and the seeming lack of correspondence with the buildings’ abstract language, these frescoes could be seen from a variety of perspectives, repeating but extending the didactic character of his houses. Compared to them, however, they were more articulate projects, with a more assertive presence and a greater sense of appropriateness.

O’Gorman’s growing reputation led him, almost immediately, to become part of the committee in charge of establishing the guidelines of technical education in the country. As the only architect on the committee, he was also put in charge of establishing a new model of architectural education. Thus, in 1932 O’Gorman transformed a preexisting construction trade school into the Escuela Superior de Construcción (ESC).13 The immediate predecessor of the ESIA, the ESC offered the degree of “building engineer,” and in this sense materialized O’Gorman’s notion of architecture as engineering of buildings. The building engineer was conceived as someone proficient in advanced construction techniques and architectural design, and whose skills – as opposed to those of university trained architects – would better respond to Mexico’s needs for urban infrastructure.14 Largely developed by O’Gorman, the curriculum provided him with the opportunity to apply his philosophy of functionalism at a larger institutional scale and was characterized by the suppression of almost all “humanistic” and “artistic” courses. Indeed, anticipating Gropius’ more moderate initiatives at Harvard, the ESC offered no courses on history except for one dedicated to the “History and Geography of Mexico.”15 Conversely, the curriculum abounded in technical courses: nomography, statics, geology, hydraulics, topography, railways, roads, ports, sanitation, drafting, building techniques, and administration. Similar to the university, however, architectural design (composición) remained the core of the curriculum taught throughout its four years. Yet without the standard “visual” preparatory course other than one on sketching and relevé (surveying and drawing of historical buildings), architectural design was treated as a problem solving matter focused on the distribution of spaces in plan. Moreover, the buildings selected for relevé needed to be “rationally planned.”16

Figure 17.3 Juan O’Gorman, Elementary School in Portales, Mexico City, 1932–33

While O’Gorman invited likeminded professors to teach the different topics of the school, he put himself in charge of its only other humanistic course: architectural theory. This course, however, consisted of the unpacking of his functionalist theory hinging on the thesis: that “architectural composition, its form, and elements, are determined by human needs and building procedures.17 Emulating the pedagogy of his teacher Zárraga, O’Gorman defined architecture as “the shelter and locale for the work and rest of man.” The first lectures were dedicated to an explanation of the school’s goals (a “technical” education as opposed to an “academic” one) and included a session on standardization, industrialization, and Taylorism. Taken from Le Corbusier these topics were nevertheless seen through O’Gorman’s anti-capitalistic lens. Other introductory lectures were devoted to the “elements of composition,” which for O’Gorman consisted of program, site, terrain and human needs. Abstractly conceived, the latter topic amounted to “areas of use,” “circulation” and “unroofed areas,” and their design explained as a process of “reduction to their minimal dimensions.” Besides an overarching emphasis on economy, concrete aspects of human praxis were limited to the themes of visibility and acoustics in auditoriums. The introductory lectures also included sessions on style, proportion, art, regionalism, and the Greek Orders, but discussed in a way that highlighted their “dangers,” yet, the bulk of the course was dedicated to the “elements of architecture:” walls, openings, doors, windows, supports, roofs, floors, vaults, domes, furnishings, and machinery. Both in name and in spirit, this aspect of his theory course derived from Julien Guadet’s Elements et Theorie de l’Archiecture, a textbook used at the university since the turn of the century, assigned to O’Gorman as a student, and listed in his syllabus as a textbook. In addition to Guadet, O’Gorman also recommended four books by Le Corbusier: Vers une Architecture, L’Art Decoratif d’aujourd’hui, Une Maison une Palais and Precisions. These were precisely the books devoured by him as a student at the beginning of his career and were included to compensate for an otherwise encyclopedic reference. The character of the course, however, was closer to the latter; the only Corbusian topic being the “free plan” but solely conceptualized as the product of modern techniques.18 The combination of the rather antithetical figures of Guadet and Le Corbusier didn’t seem to have been problematized by O’Gorman nor put in historical context.19 Indeed, as historian Rafael López Rangel has pointed out, there was neither in O’Gorman’s course, nor in the school in general, “any systematic knowledge of history that could aid in the comprehension [of the complexity] of the architectural process.”20

O’Gorman’s bold pedagogical enterprise provoked a reaction in the architectural establishment of Mexico. Less than a year after the ESC was founded, the Society of Mexican Architects organized a series of “talks” to debate the state of architecture in the country. Its purpose was to address these questions:

What is architecture and what is functionalism? Can functionalism be considered a definitive stage or as the embryonic beginning of all architectural becoming? Can the architect be considered a simple building technician or, also, a promoter of the general culture of the people? Is architectural beauty the necessary result of a functional solution, or does it also demand the creative will of the architect? What must be the architectural orientation in the country?21

Formulated by the organizers the questions were meant to put O’Gorman and his radical colleagues on trial, an opportunity that they nevertheless took gladly, making sarcastic comments directed to their hosts.22 Arranged as a series of presentations, the talks did not allow for debate and were instead monologues of mutual indictment. Whether upholding beauty as architecture’s eternal essence or denying it on the grounds of technique and social responsibility, the speakers paradoxically exhibited a deeper commonality in their shared belief on a dual nature for architecture. More negatively, they indulged in generic definitions of architecture without addressing any specific topic of design or theory.

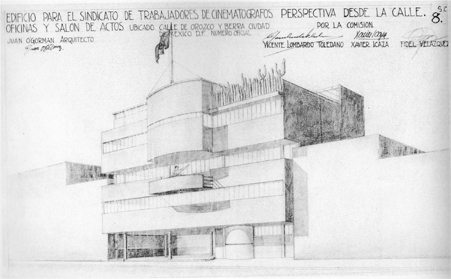

But while O’Gorman was busy defending his theory of functionalism, his private practice was following less restrictive paths. The experience of the schools familiarized him with a scale of building and institutional representation that matured him as an architect. While he continued designing Le Corbusier inspired buildings, whimsical gestures were no longer included in the buildings and they acquired more articulated physiognomies. The 1935 Toor house, a variation of Maison Cook, was a series of stacked floors subtly revealing the vertical route organizing the building. Similar “phenomenal transparency” strategies were rehearsed on the contemporary Union of Mexican Cinema Workers (Sindicato Mexicano de Cinematografistas) (Figure 17.4). Accessed through an open ground floor, featuring in a balcony for political speeches and military defense on the third floor, and terminated by a library and a terrace on its uppermost level, this building exhibited greater hierarchy and an implicit narrative of solidarity, political autonomy, and spiritual emancipation. The 1936 project for the Confederación Mexicana de Trabajadores (CTM), the largest labor union in the country, was another Corbusian exercise, this time inspired in the Centrosoyuz building in Moscow, that despite its almost exact replication of elements, closely responded and transformed to the site and the monument of the Revolution recently built next to it. The CTM building was also the first project in which O’Gorman proposed a system of cladding after years of “stripping” down buildings.23 This gave to the project a figurative and material character that anticipated many of his future preoccupations, as well as the work of other Mexican architects during the 1950s and 1960s. Despite O’Gorman’s later disparagement of the project as a demagogic showpiece for the incumbent union leader, the CTM was probably his most accomplished project.24 Working before the takeover of labor politics by the Mexican State, it was a provocative representation of the aspirations of an important actor in the Mexican Revolution and post-revolutionary politics.25

By 1936, however, O’Gorman began to realize that his functionalist theory, based as it was on an instrumental type of rationality, shared a similar logic as capitalism.26 By this time other, less socially committed, architects were erecting functionalist style buildings for the middle and upper classes of Mexico. As the building industry (now benefitted by a nascent building boom) saw the advantages of building economically and efficiently as O’Gorman first proposed, functional architecture suddenly “turned into a Frankenstein” for him.27 Thus, shortly after the completion of the CTM project, O’Gorman decided to retire from architecture and turn his attention to painting.

Figure 17.4 Juan O’Gorman, Union of Mexican Cinematographers, Mexico City, 1935

During the next decade O’Gorman produced a series of frescoes in the Mexican-realist style, which strengthened his friendship with Rivera, but paradoxically led to his return to architecture. In 1939, through Rivera’s workings and in a series of episodes that mirror his work under Nelson Rockefeller, O’Gorman was invited by the son of U.S. businessman Edgar J. Kauffman, Edgar Kauffman Jr., to paint a mural cycle in a building on their property in Pittsburgh.28 For this project O’Gorman’s envisioned a criticism of capitalism as decadent and a eulogy of the working class in their struggle for socialism. Finding his work too incendiary, Kauffman eventually dismissed O’Gorman, yet his stay in the United States was immensely important. Regularly visiting the Kauffman’s recently built house in Bear Run, O’Gorman operated a further change of mentality that reshaped his view of functionalism. From here onwards his criticism ceased to be only about cooptation by economic forces and more about functionalism’s deficiencies in topographical and cultural matters. In Fallingwater, O’Gorman “discovered” Frank Lloyd Wright and the value that his work, as opposed to Le Corbusier’s, had for Mexican architecture. Visiting the United States at the height of the “good-neighbor” policies, O’Gorman saw in Wright the most faithful interpreter of the continental landscape and the true heir of Pre-Columbian architecture.29

After his retirement and even after his Wrightian epiphany, O’Gorman continued teaching at the ESC, now transformed into the ESIA. Surprisingly his theory course didn’t change. If anything its structure was refined and its positivistic message strengthened. By 1950 it revolved around the idea that the discipline of architecture consisted of three “techniques”: distribution, construction, and installation systems.30 His decision to deliver similar content was based on the realization that the functional aspects of architecture were at the end “the most objective” and easily transmittable, whereas the “subjective” ones, in which he included the now more positive themes of proportion, aesthetics, and all things “delightful to the senses and the mind,” could not be taught and depended on the architect’s individual learning and personal imagination.31 O’Gorman’s criticism of functionalism therefore was rather a flight from a profession that was becoming intolerable to him. After his return from the United States his criticism became more focused yet this only inverted the terms of the problem without questioning its premises.

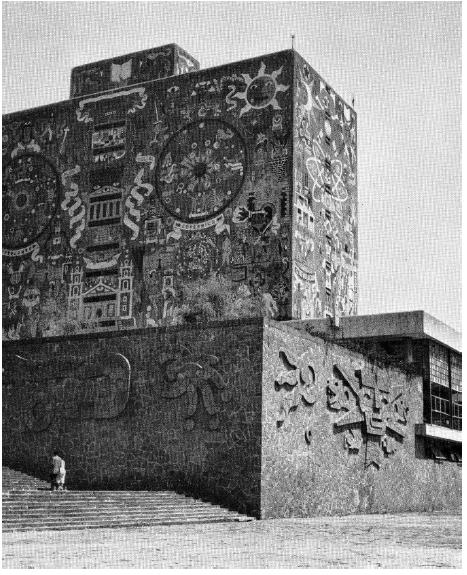

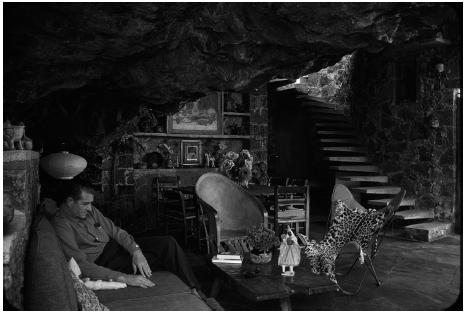

O’Gorman returned to architecture in 1949. In that year he was commissioned with the design of the most symbolic building of the new campus of the university: the central library (Figure 17.6). Although similar in many ways, the two buildings were different, and not just in size, program, or shape. Carved out from a natural grotto, the house was a literal interpretation of Wright’s ideal of organic continuity. The library, for its part, was a freestanding slab with a more assertive presence but with a subtler relation to the ground. Thought of as a domestic refuge, the house embodied O’Gorman’s escape from the profession and the world. Located in the most prominent site of the university, the library was an open institution acting as a fulcrum for the campus and the entire country. While the former represented O’Gorman’s exasperation, the latter reflected his internalization of architectural principles now largely autonomous from his theories. His eulogy of the house (a “truly Mexican” work) and his criticism of the library (a “gringa dressed in native clothing”) are testament to O’Gorman’s blindness to his own achievements and his constant subordination of architecture to ideology.32

By the mid-1960s Alberto Pérez-Gomez entered the school that O’Gorman founded thirty years earlier. Despite a number of reforms and the firing of O’Gorman himself in 1955, the school retained much of its original pedagogy. More than a decade later, when Pérez-Gómez finished his doctoral dissertation at the University of Essex, the thesis contained in it revealed, beyond the acknowledged debt to his advisors, a deeper if indirect connection to Mexico in its explicit criticism of functionalism. Pérez-Gómez, however, produced a more compelling thesis than O’Gorman’s reactionary one. Yet in its tone it retained echoes of O’Gorman’s rebelliousness and uncompromising spirit.

Figure 17.5 Juan O’Gorman, University Library, Mexico City, 1949–52

In an interview with Edward Burian, Pérez-Gómez reflected on his education within the broader context of modern Mexican architecture.33 In the interview Pérez-Gómez discusses the pervasiveness of positivism in twentieth century Mexican architectural theory while at the same time acknowledging the creativity of Mexican architects for being able to produce “fascinating” buildings regardless of the theories that drove them. The conversation revolves around the idea (introduced by Burian and later applied to O’Gorman) that Mexican modern architecture operated along a theoretical vacuum, and that its richness relied more on an intuitive or tacit understanding of cultural and topographical conditions than on ideological imperatives. It is both paradoxical and understandable that one of the most important contemporary theorists emerged from that context.

Figure 17.6 Juan O’Gorman, O’Gorman house, Mexico City, 1952

Notes

1 Alberto Pérez Gómez, La Génesis y Superación del Funcionalismo en Arquitectura (Mexico City: Limusa, 1980).

2 On O’Gorman see Clive Bamford Smith, Builders in the Sun: Five Mexican Architects (New York: Architectural Book Publishing, 1967), 16–50; Edward R. Burian, “The Architecture of Juan O’Gorman: Dichotomy and Drift,” in Modernity and the Architecture of Mexico, ed. Edward R. Burian (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997), 127–149; Valerie Fraser, Building the New World, Studies in the Modern Architecture of Latin America, 1930-1960 (London: Verso, 2000), 38–82; and Luis Carranza, Architecture as Revolution: Episodes in the History of Modern Mexico (Austin: Texas University Press, 2010), 119–167. The main sources in Spanish are Mauricio López Valdés ed., O’Gorman (Mexico City: BITAL-Américo Arte, 1999); and Antonio Luna Arroyo, Juan O’Gorman, Autobiografía, Antología, Juicios Críticos y Documentación Exhaustiva sobre su Obra (Mexico City: Cuadernos Populares de Pintura Mexicana Moderna, 1973), from where much of the biographical information derives.

3 The School of Architecture was the heir of the Architecture Section of the Real Academia de San Carlos. Founded in 1781 under the model of the Real Academia de San Fernando in Madrid (itself inspired by the French Academy) the Mexican Academy contained the first architecture school of the American Continent. During the nineteenth century it became an upholder of the pedagogy of the École de Beaux Arts.

4 In the tradition outlined in Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in First Machine Age (New York: Praeger, 1960), 14, 23–34.

5 Luna Arroyo, Juan O’Gorman, 100.

6 Juan O’Gorman, “Más Allá de Funcionalismo,” in La Palabra de Juan O’Gorman: Selección de textos, ed. Ida Rodríguez Prampolini (Mexico City: UNAM, 1983), 125.

7 As embodied for example in Hannes Meyer’s description of his collaborative entry for the 1926 League of Nations Competition: “Our building symbolizes nothing. Its size is automatically determined by the dimensions and conditions of the program.” Quoted in Claude Schnaidt, Hannes Meyer, Buildings, Projects and Writings (Teufen, Switzerland: Arthur Niggli, 1965), 25.

8 Frank E. Brown’s insights on Roman architecture may be appropriate: “[Roman] architecture was of a particular functional sort. Of its very nature, it not only contained the specific action it was framed for; it required it, it prompted it, it enforced it.” Frank Brown, Roman Architecture (New York: George Brazillier, 1971), 10.

9 See Joseph Rykwert, “Lodoli on Function and Representation,” in The Necessity of Artifice (New York: Rizzoli, 1982); and Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983), 253–258.

10 Stanford Anderson, “The Fiction of Function,” Assemblage 2 (February 1987): 18–31.

11 For Stanford Anderson the cultural relevance of twentieth century functionalism was stronger in buildings whose display of functional elements possessed a “higher level of organization” that transformed them from the level of iconography to that of fictions or stories. Ibid., 22–29.

12 Narciso Bassols, Mexico’s Minister of Education from 1931 to 1934, was instrumental in the, ultimately failed, project to educate Mexican children under an “exact and rational conception of the universe and of social life.” See Gerardo Sánchez Ruiz, “Las Condiciones Sociales que Exigieron la Opción Técnica de las Escuelas Bassols-O’Gorman,” in Juan O’Gorman: Arquitectura Escolar 1932, ed. Víctor Arias Montes (Mexico City: UAM-A, UNAM, UASLP, 2006), 36–51.

13 On the ESC see Rafael López Rangel, Orígenes de la Arquitectura Técnica en México, 1920-1933: La Escuela Superior de Construcción (Mexico City, UAM, 1984).

14 O’Gorman’s initiative was not entirely original but resuscitated a short-lived nineteenth century initiative when, under the initial influence of positivism and the rising social status of engineers, the Mexican Academy transformed the title of architect into that of architect–engineer. The mastermind of this project was the German-trained Italian Saverio Cavallari. On Cavallari see Gabriella Cianciolo Constino, Francesco Saverio Cavallari (1810–1896): Architetto senza Frontiere tra Sicilia Germania e Messico (Palermo: Edizioni Caracol, 2007).

15 López Rangel, Orígenes, 92.

16 Ibid., 114.

17 See Juan O’Gorman, “Programa de Teoría de la Arquitectura. Escuela Técnica de Construcción, Ciclo Fundamental y Ciclo Especial (1932),” in Ideario de los Arquitectos Mexicanos, ed. Ramón Vargas Salguero and J. Víctor Arias Montes (Mexico City: UNAM – INBA – Conaculta, 2011), vol. III, 48–69. See also López Rangel, Orígenes, 113–114.

18 For Hanno-Walter Kruft, Guadet’s book represented a “synthesis” of the École des Beaux Arts’ architectural theory. Hanno-Walter Kruft, A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994), 288.

19 At any rate, O’Gorman warned his students that all the books listed were “written in French and thus no reading could properly serve as a textbook in the course.” O’Gorman “Programa de Teoría de la Arquitectura,” 68–69.

20 López Rangel, Orígenes, 114.

21 The talks were published in Pláticas sobre Arquitectura, 1933 (Mexico City: Sociedad de Arquitectos Méxicanos, 1934), and have been republished with commentaries in J. Víctor Arias Montes ed. Pláticas sobre Arquitectura, 1933 (México: UNAM-UAM, 2001), and Pláticas sobre Arquitectura, 1933 (Mexico City: Conaculta-INBA), 2001. On the talks see Valerie Fraser, Building the New World: Studies in the Modern Architecture of Latin America 1930-1960 (New York: Verso, 2001), 51–52; and Luis Carranza, Architecture as Revolution: Episodes in the History of Modern Mexico, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 151–158.

22 These architects were Juan Legarreta and Álvaro Aburto, both of whom were invited by O’Gorman to teach at the ESC.

23 O’Gorman’s schools were characterized by Esther Born as having “no frills, no fuss, and no feathers,” and “stripped for action.” Esther Born, The New Architecture of Mexico (New York: William Morrow, 1937).

24 Luna Arroyo, Juan O’Gorman, 124.

25 See John Mason Hart, Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1987), 52–73.

26 “It is easy to realize the productive value that a principle like maximum efficiency with minimal effort” has for the capitalistic system. Juan O’Gorman, “Arquitectura Capitalista y Arquitectura Socialista” Edificación 2, no. 6 (November/December 1935) and Edificación 3, no. 1 (January 1935/February 1936), 11–17, 14.

27 “‘Abandoné la arquitectura porqué se me convirtió en un Frankenstein’: O’Gorman,” in Prampolini, La Palabra de Juan O’Gorman, 212–216.

28 On O’Gorman’s Wrightian conversion see Keith Eggener, “Towards an Organic Architecture in Mexico,” in Frank Lloyd Wright: Europe and Beyond, ed. Anthony Alofsin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 166–257.

29 Smith, Builders in the Sun, 18.

30 O’Gorman, “Más Allá de Funcionalismo,” 125–131.

31 Ibid.

32 See “Comentarios acerca de la casa de la Avenida San Jerónimo no. 162,” and “Dijo O’Gorman de sus murals en C.U. ‘Por lo menos que fuera una cosa que no disgustara al público,’” in Prampolini, La Palabra de Juan O’Gorman, 157–159, 298–301.

33 “Mexico, Modernity, and Architecture: An Interview with Alberto Pérez-Gómez,” in Modernity and the Architecture of Mexico, ed. Edward Burian (Austin: Texas University Press, 1997), 13–60.