Kangan and Banak, Iran

This chapter will explore the notion of urban identity in a specific locality in Iran, especially in regard to the role of sustainable development within current conditions of globalisation. Urban identity is a theme closely related to the culture, climate and lifestyle of the people who live in that particular town or city. Two settlements will be investigated: Kangan, a coastal port on the Persian Gulf in south-western Iran, and Banak, a smaller inland town that is almost attached to Kangan.1 As in effect a linked settlement, it sits on the main coastal road that connects two major sea ports, Bushehr (some 210 km to the north-west) and Bandar Abbas (about 400 km south-east).

Iran is one of the most politically significant developing countries in the Persian Gulf. It is also culturally and climatically diverse, and considered to be a family-based and religious society with its own traditional social structures. Iran has an oil-dependent economy and is recognised as one of the major oil producers as well as main fuel consumers in the world. After the Islamic Revolution 1979, the state has tried to establish a democratic-religious system. In doing so, it has adopted a closed policy towards the global marketplace and has encouraged resistance against any cultural, economic and political influences from western nations. Although these conditions have left Iran less influenced by external forces, the country with its very young population has experienced internal unrest in recent years, which can be interpreted as a search for a contemporary identity and a demand for liberal democratic policies. The social movements that spread around Arab countries, and became known as the ‘Arab Spring’, hint at more changes in the future of the region. Iran will not be immune.

In addressing urban development at the private, public and global scales, this chapter explores themes of cultural identity and climatic comfort as well as economic status in relation to global changes. This will be done by analysing transformations in the socio-cultural environment as well as the physical environment. In particular, the chapter will ask a number of questions. Firstly, how is global capitalism affecting or changing Kangan and Banak, whether as a result of economic boom or recession? Secondly, how are new conditions of globalisation affecting or changing traditional architecture there? How does the local community deal with issues of cultural identity in light of global social changes? How does the community try to represent and symbolise its cultural identity? How does the community use the settlement and what are the everyday patterns of habitation? How do people deal with the local climatic conditions? And lastly, how is climate change affecting or changing the specific town or city, and what steps are being adopted to deal with this problem? (See Plate 21)

13.1 Linked cities of Kangan and Banak on the eastern coastline of the Persian Gulf

LOCATION AND HISTORY

Kangan and Banak are located in the extreme south-eastern end of Bushehr Province, and they form the heart of Kangan County. At an average altitude of just 9 m above sea level, both settlements are very low-lying. Kangan is a port neighboured by the waters of the Persian Gulf to the west and the Zagros Mountains and city of Dashti in Fars Province to the east. Banak, meanwhile, is a town which is now all but linked to Kangan, with the consequence being that both settlements profoundly interact with each other. As a stopping point on the coastal road in southern Iran, as well as a seaport connected to others in the Gulf region, the combined Kangan-Banak settlement acts as a halfway-house for people and products which come, stay or leave. Their combined settlement area is 1,402 km2, nestling on the spot where the gentle slopes of the Zagros Mountains meet the sea.2 The port has a harbour that is 9 m deep, making it one of the most suitable places for sea-related activities in the area. However, large ships cannot land in Kangan, and instead it is used for fishing boats and smaller ships known as lenj.

Kangan County is a largely traditional area, with Kangan only being officially a municipality since 1953 (i.e. for only 60 years). It is also one of the most interesting areas along this northern coast of the Persian Gulf due to its natural and cultural attractions. In fact, the settlement of Kangan-Banak ‘plays an important historical, economical and strategic role in the region’.3 As Sani Al-Doleh writes in his invaluable book, Merat Albaldan, the historical background of this region dates to 336 BC when Alexander the Great sent food supplies to his troops via the port of Siraf (now Bander-e-Taheri), some 40 km to the south.4 Siraf was for a long period an important trading and commercial harbour for the Persian Gulf, and, as historians note, Kangan only began to develop after Siraf was heavily destroyed in the 10th century AD. By 1916, albeit still a small settlement, Kangan had grown enough to have its own customs house.5 As well as the wonderfully fish-populated sea, the beautiful inland mountains are the other key natural resource, along with the Mianloo mineral thermal springs to the north-east and Mond River to the north. Traditionally, the local architecture has adapted itself to the natural environment and climatic conditions: Nasoori Castle in Siraf’s old port is one of the most fascinating examples and has survived for hundreds of years.6

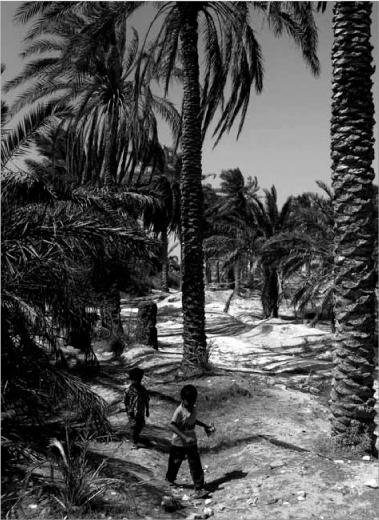

13.2 Palm trees as the main greenery in the area

13.3 Impact of recent droughts on the local environment

GEOGRAPHY, NATURE AND CLIMATE

The climate of the Kangan and Banak area is hot and humid with extreme summers and mild winters. Statistics report that the highest temperature reaches 52°C, and can go as low as 0°C in winter.7 In the summer, a wind called the ‘120 Day Wind’ blows across the region. It is a dry and harsh wind described as Tash Bad – which means ‘Fire Wind’ in local terminology – and it sometimes impacts strongly on urban life and human comfort. In addition, earthquakes and floods are two of the major natural threats which need to be considered in designing any development.8

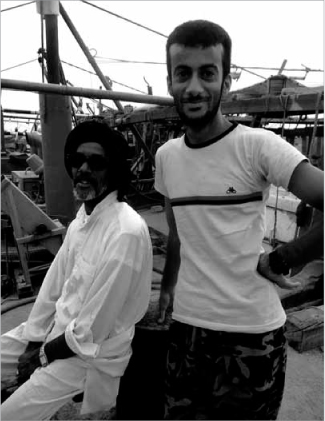

13.4 Old and new generations reflected in their attitude and clothing

Due to its seafront location, Kangan is especially sultry, with high humidity. The region has a low level of precipitation which only lasts for four months from December to March, meaning that Kangan and Banak are constantly confronted by a lack of water resources. There is no surface water or permanent river flowing through the settlements, although, since it is situated between mountains and sea, a number of seasonal rivers do occur, even if they are mostly completely dry. This condition, coupled with physical interventions made to the waterways, has caused seasonal flooding especially in recent years. Mountain trees in the forest park to the east, along with some areas of green croplands to the west, next to the coast, add to the natural potential of Kangan and Banak. Any agricultural production, however, needs to be based on tapping into underground water resources, and indeed local people have traditionally built down water shafts to acquire water. Typical crops include tomatoes, dates, wheat, barley, onions, aubergines and other vegetables. Otherwise, because of the poor soil quality and climatic conditions, the natural vegetation of the area consists of short plants with rough leaves.

POPULATION AND CULTURE

According to the last official statistics from 2006 there were 95,349 people in Kangan County, constituting about 10 per cent of the population of Bushehr Province.9 Just over half of this population (52 per cent) reside in urban centres in the province whilst the remainder (48 per cent) are in rural areas. In comparison to surrounding counties, agricultural lifestyles thus play a more significant role in Kangan County. In addition, more than 80 per cent of the people, especially men, have only a basic education. The lack of higher-level educational institutions results in a heavy dependence on other cities within Bushehr Province as well as an inability to provide a suitably qualified workforce for local industries. The fact that 44 per cent of the population are between 15–29 years old reveals that Kangan County has the highest proportion of young people in Bushehr Province, creating a real need for proper action to meet their needs in terms of education, jobs, entertainment etc. In addition, it appears from the 2006 census that Kangan itself contained around 24,000 permanent inhabitants occupying 3,035 housing units.10 A further sizeable number of the local population in Kangan County, around 12,000 men, were temporary skilled and unskilled labourers who worked mostly in the Pars-e-Jonoubi gas field or the industrial zone in the Assalouyeh corridor to the south. Today, it is estimated that Kangan’s population is still around the 25,000 mark, thus making it significantly larger than Banak with just 9,000 inhabitants.

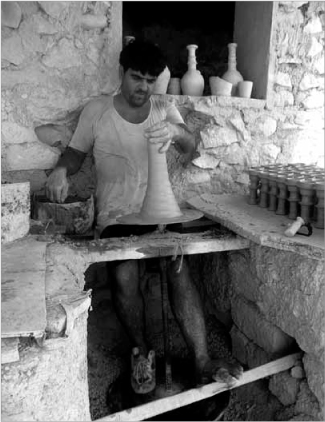

13.5 Pottery as a traditional local micro-industry

The vast majority of the people in Kangan and Banak are Shi’ite Muslims, and a minority are Sunni Muslims, as is usual in Iran. The spoken language is mostly Farsi (Persian) with a local dialect. Due to the close economic relationships with Arab countries on the other side of the Persian Gulf, a fair amount of local people also speak Arabic. Having experienced often volatile histories, a diverse range of ethnic and religious groups have settled in Kangan and Banak at various times, leaving their physical and cultural traces. For example, in Kangan there is an old Jewish temple which has been destroyed recently but which remains a visible trace of other cultures that have marked the place. This multicultural experience in collective memory enables inhabitants to adapt the culture of ‘others’ with less resistance. In his book on The Persian Gulf in the Age of Colonialism, Valara has noted: ‘In 1911, two hundred and fifty new family units settled in Kangan port; while two hundred of them were Jewish and the rest were Arab or non-Arab (Fars).’11 Today, however, almost all people are Fars, i.e. Persian Muslims, and there are no more Jews at all.

13.6 National gas industries are turning Kangan-Banak into a heavily industrialised area

KANGAN’S ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS

The initial core of Kangan was composed of two main districts: Mahaleh Arabha (‘Arab area’) and Mahaleh Koozehgari (‘Pottery Area’). Despite a generally peaceful relationship between religions, this urban division was apparently based on the grounds that the ‘Arab area’ was settled by Sunni Muslims and the other by Shi’ite Muslims. According to the latest master-plan for Kangan, once the old town developed, it became divided into six districts, nine urban areas and one urban centre.12

Due to its coastal location, the main economic activity in Kangan is fishing and sea-trading – with, as noted, a small amount of agriculture next to the settlement. Industrial expansion in Kangan County generally has already begun to grow due to its close proximity to Iran’s largest gas and petrochemical industries. The huge gas facility at Pars-e-Jonoubi is one of the largest energy sources in the world, transforming this region rapidly from sea-based activities to becoming one of the main industrial poles of Iran in recent years. Assalouyeh is one of the ‘special economic zones’ (SEZ) and it contains the largest concentration of industrial functions in Bushehr Province. A second industrial zone, called the ‘Kangan Site’, and planned to become twice the size of Assalouyeh, has been started just 10 km from Kangan. Furthermore, one of Iran’s most important cement factories, Sarooj-E-Kangan, is situated 12 km from the town, and is heavily involved in exporting to Europe and Asian countries. All these initiatives have attracted huge amounts of economic investment, turning the image of Kangan County into an industrial region. Liberalised trade policies in the free-trade zones along the southern Iranian coast have resulted in a surge in imported foreign products, and indeed the SEZs were set up especially to encourage the transit of goods by freeing them from normal taxation duties.

Bearing in mind the presence of these mega-plants along the coastline, and the fact that about 50 per cent of local people are now involved in related service trades, there are no sizeable industrial activities within Kangan itself. For many years, handicrafts were prevalent in Kangan County, particularly in rural areas, and a few fascinating but small industries such as pottery can be still found in the town. Due to the importance of water in this hot region, pottery production has generally focussed on jugs, water jars, pitchers, and ghelyan.13 But it is still sea-related occupations that form the economic backbone of Kangan, with 35 per cent of its inhabitants being involved in fishing and sea trading, 10 per cent in agricultural activities, and 5 per cent in governmental activities.14 Yet research also shows that new factors such as consumerism are increasing fast, meaning that productive trades such as pottery, baking and livestock rearing are declining. Recent economic changes have also caused many sea traders to switch to property investment because of the high demand for properties in the area.

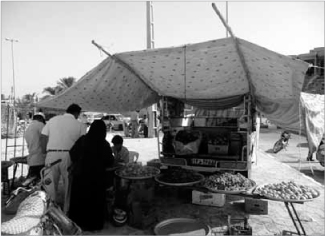

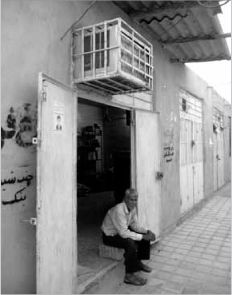

13.7 Example of a self-made shop built by local merchants

13.8 Newly-built market using concrete and steel which is very quiet during the day as it is so hot

The reasons for this investment are clear. Being a port, Kangan has a close relationship with the countries across the Persian Gulf, such as Qatar and the UAE. Given that cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi are already so developed as economic and business magnets, places like Kangan are bound to be attracted to those power poles: the high proportion of young people in Kangan County provides a ready labour force. This is turning settlements like Kangan and Banak into small-scale consumer markets for Dubai and Abu Dhabi. Furthermore, with the escalating development of energy industries in Kangan County, some companies have begun to buy houses and properties from inhabitants in rural areas. In some cases, they even occupy an entire village with their workers, displacing local people. Instead of creating permanent jobs and sustainable conditions, the companies simply pay people enough to move to new houses elsewhere. This creates a jobless community cut off from its roots, and indeed from real life, once the payouts are spent.

Moreover, due to the huge national-scale industrial developments in Kangan County, a considerable number of ethnic groups from all over Iran, and from nearby countries, have migrated to this area to find jobs and a better life – particularly so during the current economic recession, and with Iran suffering some of its worst-ever droughts. A consequence of migration from rural areas is the proliferation of different ethnic and cultural communities that have not integrated into the host settlement, nor have proper dwellings. One can see the spread of slums in places like Kangan. It is also creating a great deal of social tension. As a result, many of the youths of Kangan and Banak dream of a life in more ‘advanced’ cities like Dubai or the main Iranian cities such as Tehran or Shiraz. This passion is driving a good many people out of Kangan County, adding to the already tense status of Kangan and Banak.

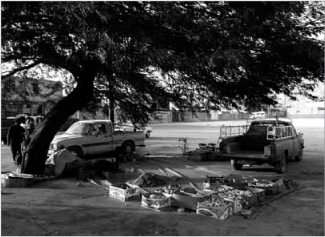

13.9 Vendor creating his shop under the shade of a tree

KANGAN: FROM CULTURE TO ARCHITECTURE

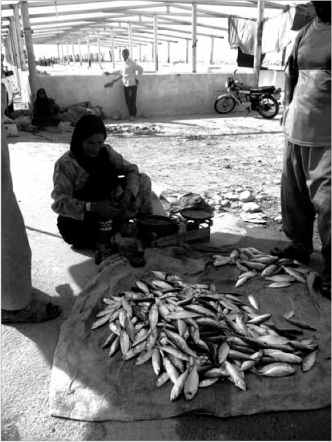

Daily activity in Kangan typically begins at 3.00–4.00 am when the fishermen head out to sea to catch fish for the morning market, held every day starting around 9.00 am or so. The fishermen usually sell their catch in an informal open bazaar along the coastline. However, there is also a special covered fish market beside the main coastal road since a number of people from other regions come to buy fresh fish. All these activities, as well as the other shops in Kangan, usually close down at noon, with people returning to their houses. Some offices that will have started work between 7.00–8.00 am will continue to work on to 2.00 pm by relying on air-conditioning or other mechanical cooling. But because of the extremely hot weather for most of the year, the majority of people go home for a rest with their family when the sun is at its strongest. Social and economic activities restart again around 6.00 pm and continue to 10.00–11.00 pm as the weather is cooler. In the evening, once the sun sets, people often sit in front of their doorways with family members or neighbours to talk and smoke water-pipes. Others will go to places in Kangan to shop and promenade, such as on Vahdat Street in the town centre, or else head for the coastal park for refreshments and entertainment. This form of lifestyle helps to reduce the energy spent on cooling buildings as people go out in the evening when otherwise there would be a peak for lighting their homes or watching television. Public open spaces in the evening also bring natural environmental comforts, creating suitable conditions for social life at the local and urban scales. The selling of foodstuffs such as fish, tomatoes and dates are some of the most important activities.

13.10 Traditional narrow pathway providing shade as well as a human-scaled space for social interaction

Inside dwellings in Kangan, since the houses have no furniture to sit on, people habitually take off their shoes at the entrance, sit down on the carpet, and lean upon special backrests. Given that heat always rises, the lowest levels of rooms are generally the coldest, and hence the habit of sitting on the floor helps one to breathe and cool down; as such, it again exemplifies a way to use the natural coolness of the ground. Extended families are traditionally common in the Gulf region, and children usually still make their homes in the family house after they marry. Old houses sat next to each other, and indeed neighbours lived so close to each other they could go into the next house via its roof or alleyway. In addition to the environmental role of casting cooling shadows, the narrow alleys also reinforced the community through social interaction within a human-scaled environment. It meant that local people acted as a ‘neighbourhood watch’ scheme, protecting their territory against any perceived social threat. This security, with no need for technology like CCTV, came from the close relationships and sense of belonging in the locality. Recently, however, with the emergence of small nuclear families and increasing individualism, the collective structures of traditional communities like Kangan have undergone sudden changes in their social structures and security systems. Likewise, roof terraces – which offer such a large potential surface area – once had a much more specific social function in the built habitat of cities like Kangan. Mr. Koohkan, a 40-year-old municipal employee, told me:

13.11 A new wide asphalt street which provides no shade and divides the community

When we were young we mostly slept at night (except for summer) on the roof of our homes, which was made easy with the use of a kapar [a lightweight structure of textiles and timber]. In the old days, people slept all nights on the roof since there was no cooling system. Some affluent groups built a room called balakhaneh or manzar, but most other people made the simple kapar to use the night wind on the roof against the warm conditions.

13.12 Woman selling fish under a self-made shade in front of the formal marketplace behind

Today, this simple and economic way to confront the hot climate is commonly replaced by problematic and costlier air-conditioning systems, meaning that roof surfaces are now mostly left unused and thus wasted.

13.13 The formal structure for the marketplace is left unused by local people

THE URBAN FABRIC OF KANGAN

The general urban organisation of Kangan is in a linear pattern along the coastline. The town is composed of a main boulevard in an east-west direction, and from it branch off a number of local streets in a north-south orientation to give access to the residential areas. Today, as noted, this extremely wide boulevard – which also plays a larger role as a transit route that connects Bushehr to Bandar Abbas – divides the growing town into two distinct parts.

Although the main road contains some economic activities, it is in fact one of the branched streets, Vahdat Street, which acts as the pivotal urban centre in social and economic life. It is full of various shops and connects the separate areas on both of its sides which have been settled by Sunnis and Shi’ites respectively. However, the narrow pavements, compared to the width of the road, reduce its importance as a social space for interaction. Moreover, due to increasing traffic, its role seems to be becoming more colourless. Street widening does not lead to sustainable development, but destroys the valuable social structures in cities. Moreover, by giving more respect and hierarchy to vehicles rather pedestrians, it only encourages more traffic and causes worse air pollution. Furthermore, other urban elements such as roundabouts do not represent local cultural identity; all these urban signs need to be carefully reviewed in terms of how appropriate they are.

In Kangan, apart from educational and medical buildings, the key social spaces are generally concentrated in specific public areas which have a clear economic purpose. Aside from the main boulevard and Vahdat Street, it is the morning fish market, evening market and coastal park that are vital for daily life. Whereas Kangan’s traditional morning fish market happens along the coast, the evening bazaar is along the side of the main road to catch more passing traffic. Interestingly, although a formal covered market was built by the municipality near to the sea to help the morning market, it is not used by local people; likewise, another market specially built for the evening market is also unoccupied. Instead, because of the lack of shade in these markets, vendors have themselves created a variety of interesting shelters to protect them and their customers. These informal self-built structures tend to be simple, lightweight, temporary and flexible, and are usually of local materials. Such occurrences point to the importance of community participation in the planning of cities.

Apart from the traditional bazaars, other newer commercial outlets have sprung up, mostly concentrated in the town centre or main road, such as the Pardis Trade Centre. The aforementioned influx of foreign goods floods into these new markets from places like Dubai and China, meaning that they have a considerable influence in promoting a consumerist lifestyle – thereby altering Kangan’s urban image (see Plate 22). In comparison to traditional markets, their neglect of environmental issues by using air-conditioning and electric lighting poses a threat for urban development.

In addition, the lack of green space in Kangan produces a rather dry and dusty image for the town. In this climate, public green spaces are a social and environmental necessity for urban life. The main green space in Kangan is the long linear coastal park on the waterfront to the south-west of the town with its sea breezes. Used mostly in the evening, it hosts a range of informal social facilities for sports, leisure and picnic areas. Although it is mostly has little shade, local people still use it for picnicking, drinking tea, smoking water-pipes and using the exercise machines in the cooler evenings. However, since these gatherings are mainly based on family or friendship units, these can tend to form into cliques which prevent mixing with other groups. Thus, this park doesn’t yet play a fulsome role as a social space compared to Kangan’s bazaars. It is also vital there should be more public green spaces at the local level to bind neighbouring communities within a growing town, especially in terms of connecting newer inhabitants with more established ones, as well as mixing classes, genders and ethnicities.

Kangan’s natural attractions, along with its fish market, make it a suitable place for tourists to stay, not least as an interim base for Iranian tourists travelling on to destinations such as Bandar Abbas and Kish. But because Kangan doesn’t have enough short-term accommodation, travellers usually stay in the coastal park and pitch their own tents. Again, due to the climate, this tourist season only lasts for a short three-month period in winter when the weather is sufficiently mild. It means new public spaces on the seafront, which also get so busy during the Nowruz (Persian New Year) celebrations in March, are virtually unused for most of the year. To overcome this problem in summer, proper shading and lighting, along with better paving, could help them to function for other social activities.

Recently, the arrival of new technologies has begun to change the lifestyles of Kangan’s inhabitants from their previous dependence on sea to a dependence on industry and machinery. Instead, it would seem that by employing traditional technologies related to people’s capabilities, culture and climate it could empower the community more. Likewise, increased water pollution from industrial waste and from urban sewage being discarded into the Persian Gulf – as well as global warming more generally – presents a real threat to the local ecosystem. The danger of epidemic diseases is being spread in Kangan through a lack of drains in the poorer residential areas. There is also in Kangan a virtually non-existent public transport system, creating an over-dependence on private cars and vehicles. Due to the hot climate, people mostly prefer to travel in cars with their cooling systems as opposed to walking. As well as reducing the opportunities for social interactions in urban spaces, it is another cause for environmental pollution and the wastage of fuel resources.

Traditionally, most houses in Kangan were self-built without any supervision by the municipal authorities. Indeed, new residential areas are still being expanded rapidly with little regard to architectural guidelines or urban master-plans. In recent years, due to physical restrictions on space, Kangan’s growth has mostly taken place in areas away from the sea to the north-west of the town. These new districts are represented by a grid organisation with wide roads, typical apartment blocks of 3–4 floors in height, some self-built houses and several tall buildings. Hybrid architectural styles are being used that are principally the same as in other Iranian cities with completely different climates and cultures. It means that urban changes are hardly resulting in a proper relationship between new and traditional styles. For example, the courtyards in traditional houses played a crucial role as social spaces where family members gathered, as well as environmental elements to circulate air. Nowadays, people live in apartments that are completely strange to local lifestyles or community needs. The lightweight kapar roof structures that were once common devices to deploy wind flows against the hot weather are not being adapted for the new constructions in Kangan.

BANAK’S SOCIO-ECONOMIC COMPOSITION

Due to the location of Banak – and despite its hot and humid climate, its poor soil and water shortage – the main economic activity is agriculture. Activities related to the land have thus been linked to local cultural identity for centuries. Nevertheless, the huge gas resources at Pars-e-Jonoubi are causing massive physical changes in the region, as noted in regard to Kangan, as indeed is the nearby cement factory at Sarooj-E-Kangan. Hence the major local occupations are again agriculture, fishing, sea trading and – increasingly for younger people – either industrial jobs or related service activities. Given that most local people are poorly educated and low-skilled, they often work as labourers for big companies (whereas the higher status jobs go to experts from large cities such as Tehran). Moreover, growing numbers of Banak’s inhabitants are amongst those being attracted to Iran’s major cities or other centres in the Persian Gulf region, such as Dubai, now that sea transport and visa controls are much easier.

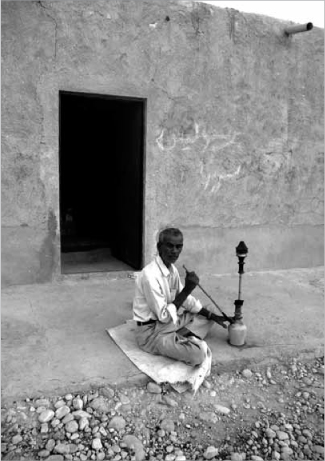

13.14 Elderly resident of Banak smoking his water-pipe in the evening in front of his house

This is a situation which can be found in many other small communities, and this mass-migration is weakening local identity, self-confidence and self-sufficiency. Banak’s people, who are keen to stress their own identity, are always having to compare themselves to their more developed neighbour, Kangan, resulting in them competing for a similar lifestyle. Although this could be seen as a dynamic motivation for advancement, it is also a threat which destroys local capabilities. Thus in proposing any development for this small and relatively under-developed community, it has to be emphasised that Banak cannot simply follow the port settlement of Kangan. In fact, Banak is unique in being able to be promoted as an agricultural town, something that is relatively scarce in this hot region. It also suggests that Banak’s community should focus on the exchange of goods with Kangan and other sea-based settlements around; taking it back to past traditions when people exchanged, say, dates for onions.

From the clothing style of Banak’s inhabitants, one can see how local people have adapted environmentally, culturally and economically to their context through simple techniques. The white colours, lightweight materials and soft textures of the clothes, as well as the shape which enables air to circulate and also allows sufficient covering of the body as people need to follow the Islamic dress code. The main local food was traditionally made of bread and dates; as a case in point, gamneh is made from wheat flour. Although the inhabitants of Banak generally carry out some kind of economic activity, such as a bakery, in their private homes, the public focus is in the town centre or either sides of the main road passing through. The rows of shops on this main road tend to have a regional function whilst the bazaar shops in the central area mainly serve local inhabitants. In addition, a weekly market called the Monday Bazaar happens close to the central, permanent market, but according to some local people, the cheap goods sold by its vendors are causing some of Banak’s shop owners to shut down their businesses. The central bazaar with its unshaded aisles, and its attached shops built of steel and concrete, becomes really hot by mid-day on most days. Again this prompts people to go home to rest with their family in the afternoon, meaning that everywhere is usually closed for that time.

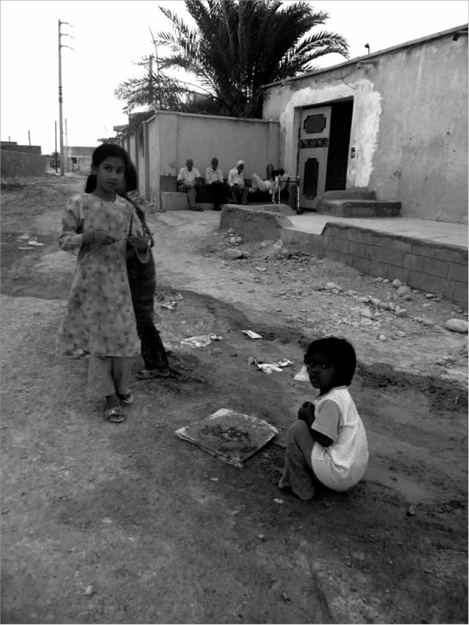

13.15 Young girls playing in the street in Banak

Banak has an extremely religious community; once again, the majority are Shi’ite Muslims while a minority are Sunni Muslims. These religions have been historically integrated within the settlement, and today also these different ethnicities continue a peaceful life beside one another. One of Banak’s inhabitants, Mr. Jamali, told me that the Sunni minority participates noticeably in the religious and cultural events in the town, whether in public or private. For example, the religious mourning ceremony called Tasoua-Ashoura, which is dedicated to Shia, is of great weight in Banak, and most people from different groups take part in it. Other religious events which bind the two religious communities include Ramadan, Eid Fetr and Eid Ghorban. Moreover, national-cultural events such as Nowruz, Sizdah-Bedar ceremonies and Yalda Night play an important role in gathering both religious organisations together, regardless of ethnicity. At a smaller and more private scale, wedding, funeral and circumcision ceremonies also provide a ground for social interaction. Traditionally they were held in a grand manner with many people being present for several days; however, such occasions are now diminishing into smaller events held over fewer days for economic reasons. This does not promise a very interactive social life for Banak’s future community.

Moreover, other people – mostly those of a younger age – go further afield, particularly to Kangan, for shopping, promenading, entertainment or refreshments. This can also be attributed to the lack of usable public spaces in Banak. At one time, as Ahmad Rashedi told me, ‘there were a mass of date trees in the coastal areas and people used to go to those gardens for picnics and entertainment’. Now, however, this feature is nearly destroyed because of the recent droughts. With the lack of education and poor job prospects, and few sports facilities, the youth of Banak are largely involved in passive leisure activities – for example, motorcycling around the town, leading to a high consumption of fuel which makes the environment more polluted. Therefore, an important priority must be to employ young people in productive activities to create sustainable development. Otherwise there are plenty of temptations. Due to the closeness to Pars-e-Jonoubi, some locals are involved in petrol smuggling, while real social disorders are also emerging, such as drug addiction amongst the younger generation in Banak.

URBANISM AND ARCHITECTURE IN BANAK

Society in Banak is generally family-based and group-based, but apart from the markets and a few other buildings, the town lacks public places or green spaces for social meeting. Apart from a few small children’s playgrounds, the main social activity which is vividly visible is an informal gathering called majles whereby neighbours gather in front of houses in the evening to chat and smoke their water-pipes. Additionally, only the shaded alleyways play a real role in neighbourly relationships or promoting urban livelihoods by offering human-scale spaces. Thus the creation of wider streets by filling in dried up waterways is now separating people (as well as adding to the threat of seasonal floods). In such a small community, it is unreasonable to prefer vehicles to people in urban spaces.

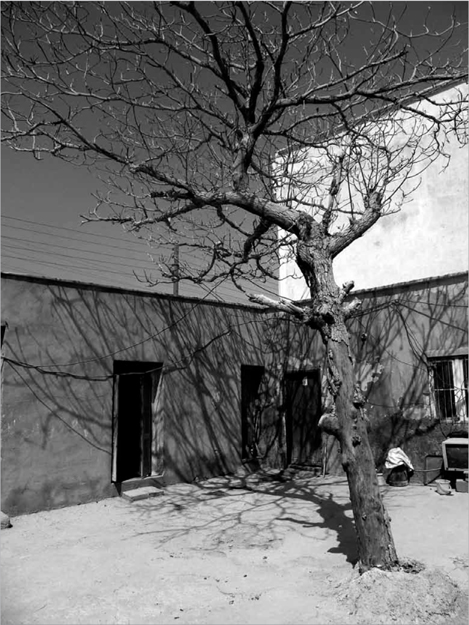

13.16 Traditional house in Banak with courtyard built out of local materials

Banak’s houses again traditionally used efficient techniques to adapt to their context and provide thermal comfort, including courtyards, thick masonry walls, roof-top kapars, etc. Aside from imported timber, building technologies used mainly local materials such as stone, adobe, mud and sarouj. The lack of water resources has resulted in using containers for tanks on rooftops. This feature visually impacts on the image of the town, as does the extensive usage of modern cooling systems. In line with local lifestyles, the dwellings in Banak mix agriculture with entertainment and domestic life. As a case in point, the house owned by Haj Abdollah Houshiar, aged 70, exemplifies a small self-sufficient settlement. It has a shop as its entrance, a well, a small garden to grow food, a stable, a bakery, several private rooms and a central courtyard. Hence, its inhabitants, an old man and old woman with no children, can easily satisfy most basic needs and even sell some of their products.

13.17 New air-conditioned apartments in Banak

As an agricultural community in a baking climate, water is the key to survival. Relying on underground water, the people built wells and then used their livestock to water the croplands. People in Banak also had to bring water from the wells every day for their own use. However, with the arrival of mechanical supplies some years ago now, these patterns of activity have changed, making lifestyles more dependent on machinery. Even less rainfall in recent years causes major droughts, while irregular rainfall patterns, plus the building over of waterways, is leading to worse seasonal flooding that often cuts off places like Banak from other parts of Iran. In other words, water resources need to be vastly improved in efficiency, and changes of habit are required to make people more self-sufficient again. This should be regarded as the priority in the urban development agenda. As Ahmad Rashedi, an educated 74-year-old man known as the ‘Banak elder’, stated:

While we can use the free water from rainfall, it has been left useless and instead it only makes floods and consequently droughts. Water, which is our vital need for life, is scarce in this place and so valuable, but it is just wasted and neither can we drink it nor use it for agriculture.

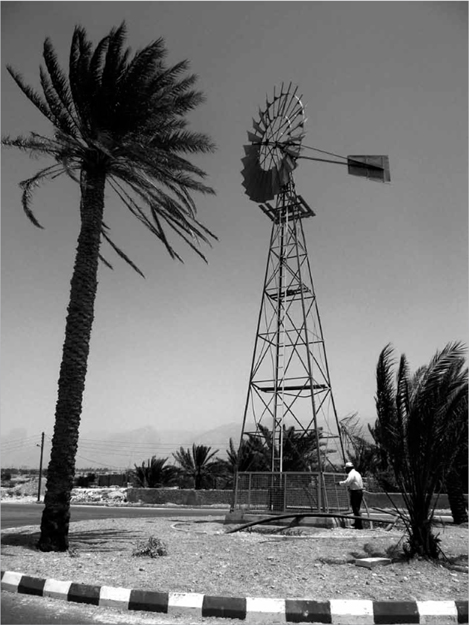

Unlike the scarcity of water, abundant wind energy is a clear potential to be developed. Although storms and severe dusty winds create some problems, the controlled collection of natural wind power offers an economic opportunity for cheap and renewable energy. For example, in Banak there is a simple old windmill, above a well that used to generate the necessary energy to bring up the ground water. In addition, solar energy is another plentiful local resource. As another kind of local renewable energy, it too could reinforce self-sufficiency within the community.

CLIMATE, COMFORT AND PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

To pull together what we can learn from Kangan and Banak, a number of traditional environmental solutions at the architectural and urban scales could be combined with new technologies to address climatic issues as follows:

• Urban development does not need to follow the coastline or major roads; instead Banak can continue to grow into its northern foothills with their milder climate, providing that new developments respect the surrounding croplands.

• Given that open-air spaces attract solar heat gain yet closed-off systems block air ventilation, then semi-open urban spaces are more suitable.

• Likewise, since attached buildings block air circulation and detached buildings increase solar gain, then semi-detached dwellings offer the best housing pattern.

• Alleyways should be higher than they are wide to provide shade and funnel the wind in the desired directions.

• Flat roofs are recommended for providing a smaller surface area against sunlight, while also being usable for activities in the milder weather.

• Light constructions and shelters (inspired by ‘kapars’) can be built on the roof for shade during the daytime and to channel the wind at nights.

• Generous ceiling heights in internal spaces, with openings at high level, help to encourage wind flow.

• Buildings should be constructed above natural ground level against flooding.

• Central courtyards are needed for their social and environmental role.

• Deep balconies, known as eivans, can prevent direct sunlight and help air circulation.

• By providing wind breaks, such as trees, buildings can be protected against dusty winds and be shaded from the harsh sun.

• Windmills can supply energy for airing and cooling, saving on the need for mechanical technologies.

• Using construction materials like timber, rubble, coral, brick and adobe – instead of concrete, steel and glass – can reduce heat gain/transfer, especially if thermal insulation is placed on the outer skin.15

13.18 Palm tree with adjacent windmill used in past times to pump up ground water

CONCLUSION

Urban growth in Kangan and Bandar is now related to new industrial plants as well as more traditional forms of agriculture and port activities, such as fishing and trade between Iran and other Gulf countries. In Kangan, development should follow the coastline to build upon its dependence on the sea and to enjoy the natural breezes. In new projects, the factors of water optimization, wind power and solar energy need to be treated as priorities. Due to the presence of the Assaluyeh gas facilities, as Reza Ahmadian (the consultant for the Kangan master-plan) observed, the town has experienced very high demand for housing immigrants in recent years. However, the physical development of the town is more horizontal rather than vertical, meaning that growth takes place mainly on its outskirts.16 While the region’s energy resources are boosting the national economy, they are also creating serious problems such as flooding.

Banak, as a uniquely green town in a hot locality, has great potential to be managed towards more sustainable development. Due to its location and agricultural basis, Banak is spreading towards the north, away from the coast, into the milder foothill areas. However, urban development is not just about physical issues, as quality of life cannot always be assessed by two-dimensional or quantitative measures. Factors such as socio-cultural and economic conditions need to be balanced with environmental issues. Hence it is necessary to promote cultural attitudes such as user participation, social engagement, urban identity, etc. Jeremy Till writes: ‘In order to develop an architecture that is particular to its condition, there are two imperatives – the environmental and the social – that do this.’17 And according to the UN Commission on Environment and Development: ‘sustainable development is the development that meets the needs of present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’18

Hence the crucial point is that sustainability is not just about the environment but is also a multi-dimensional concept emphasising quality of life for the future. Current pressures for economic growth in developing cities such as Kangan and Banak are so strong that it is creating a huge need for ‘physical development’, which in practice leaves less room for ‘quality development’. But, given the recent global challenges (including our economic and ecoenvironmental crises) every localised society is responsible to contribute as much as it can. Since globalisation conditions every innovation, as well as every crisis, any neglect poses a threat for both the developing local community and developed global society. This recognition highlights the role of urban management in social justice and sustainable development. Furthermore, given the recent socio-political protests by the younger generation in Iran, in their search for a contemporary identity, every localised society will be trying to find its own position to survive in the globalising world. We all need to be socially and environmentally responsive to the pressures of urban settlements like Kangan and Banak which are facing the coming changes.

NOTES

1 ‘Kangan County’, Wikipedia website, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kangan_County (accessed 7 July 2009).

2 Kangan Municipality official brochure (2009).

3 Ibid.

4 Here I am referring to the nineteenth-century book by Sani Al-Doleh, Merat Albaldan.

5 Maab Consulting Engineers Co., Kangan Master-Plan Studies (2005).

6 ‘Kangan’, Iran Tourism Organisation website, http://www.itto.org/city/?cityid=126&name=Kangan (accessed 15 August 2009).

7 Kangan Municipality brochure.

8 Maab Consulting Engineers Co., Kangan Master-Plan Studies.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 As quoted in ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Kangan Municipality Brochure.

14 ‘Kangan’, Iran Tourism Organisation website, http://www.itto.org/city/?cityid=126&name=Kangan (accessed 15 August 2009).

15 Vahid Ghobadian, Solar Building (Tehran: Iranian Architectural Centre, 2008).

16 Kangan Municipality brochure.

17 Jeremy Till, ‘Ethical Imperatives’, RIBA Journal, vol. 115, no. 5 (May 2008): 50–52.

18 ‘Brundtland Report’, published as World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987).