Kish Island, Iran

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

My first impression of Kish, as we come in to land, is of a dry plate of stone, sitting in the sea, undercut by the waves. Its baked surface is spotted with low-lying shrubs. Having landed, and as we head into the city, I can see that its urban design owes more to traffic engineers than to anyone else. Although trees are healthy, the grass is green and roads are in good condition, nonetheless its never-ending central reservations serve to prevent intuitive movement. Pedestrian crossings are few and far between, and buildings tend to step back from the street rather than stepping forward to greet visitors. The street edges are amorphous; there is no clear pattern or plan. What is clear is that this will not be an easy place in which to get my bearings. I cannot really see the sea – there is no corniche here like in Doha or Muscat or Cannes. But I can tell that this is a tourist resort, both from the zany holiday graphics and the host of hotels wherever I look. It is also clear that this is no ‘Earthly Paradise’. Instead, our car moves from roundabout to roundabout, from manicured boulevard to desert scrubland, past lumpy new buildings and half-finished steel and concrete frames. Eventually we arrive at our hotel. It is hot, painfully hot, mainly due to the extreme humidity, but gratifyingly it seems that Kish Island is a place where some people do walk and bicycle, even at midday, even in August, unlike so many cities of the Gulf region. In fact, the weather here is rather pleasant for nine months of the year.

We are now in the main part of the island. ‘It doesn’t really have a name, so people just call it the city centre’, Behzad Shahandeh, the Tourism Promotion Director, tells me the next day. The term ‘city centre’ certainly appears to be a misnomer. For a start, with a resident population of just 25,000, Kish is at best a town and not a city. And as Mr Shahandeh is the first to point out: ‘Kish doesn’t have a centre – it has no sense of orientation. It’s amorphous; it lacks the classical harmony we are used to in Iran.’ However, as I gradually discovered the development potential on the island and realised just how many large projects are currently underway or in the pipeline, I came to decide that ‘city centre’ is perhaps an appropriate working title for this area of the island.

14.1 Author’s annotated sketch map of Kish Island

14.2 A typical Kish road scene

14.3 The abandoned casino on Kish Island

Ferdousi Street is the actual main avenue of Kish, but in spite of its line of hotels, amusements and shopping malls, this cannot really be classified as an urban centre, as it fails to give any form to public space. Strangely, as far as I could discover, there is no mosque in the ‘city centre’. ‘That’s because no-one really lives there’, claims Majid Karimi, my companion and guide. Instead there is only an abandoned casino, shaped like a spiky crown, at the end of this major axis, backing onto the beach – but more of that later.

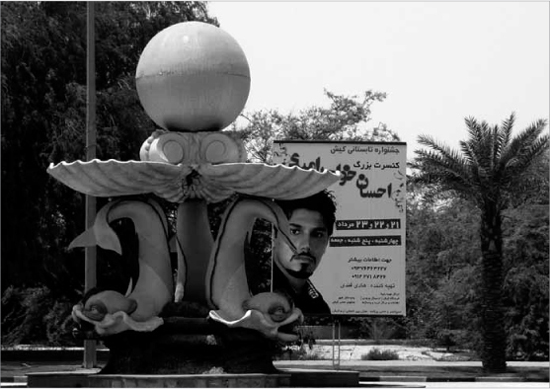

14.4 The romance of the Persian Gulf is omnipresent on Kish Island

SOME FACTS ABOUT KISH ISLAND

Kish is a low-lying island of coral rock, 90 km2 in area, a few kilometres off the Iranian coast in the Persian Gulf. On a clear day you can easily see the mountains of Iran to the north. The island is fairly flat but there is some distinctive topography, with the highpoint at the centre of the island being just 30m above sea level. It is an ancient trading post, part of the famed ‘Silk Route’ across the Gulf from Bombay to Basra, and it is now one of Iran’s primary resorts. The main tourist district is situated on the east coast. Kish has a large port in the north-east of the island, which currently handles over 1 m tonnes of cargo each year, with a four-fold increase projected by 2025. All statistics indeed show that Kish is booming. The airport in the centre of the island receives 1.2 million tourists every year, again a figure which has doubled since 2004, and which is predicted to double again by 2025. Likewise, the present population of 25,000 has doubled since 2004, and it too is likely to double again by 2025. Of the population, several thousand are students on courses here, while only about 3,000 citizens (12.5 per cent) are actually native to Kish. The vast majority of people are Iranian nationals but the percentage of foreigners is increasing at a rate some fifteen times faster than that of nationals. Projections are estimating the ultimate population at a maximum of 85,000.

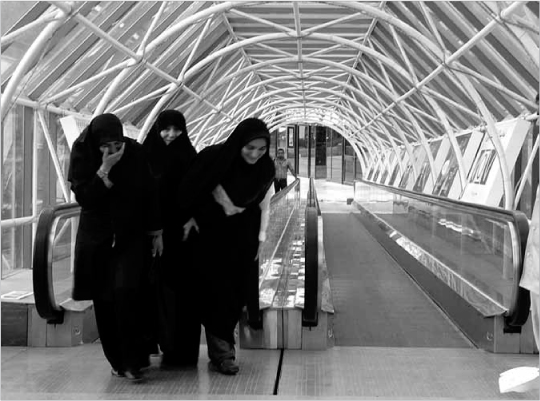

14.5 Female visitors to the Pardis Mall on Kish

Back in 2004 a third of the surface area of Kish was occupied; today a half of the island is occupied or else committed for development, the majority of it dedicated to new holiday dwellings. By 2025, it is predicted that 60 per cent of the land on the island will be built up. There is a strategic master-plan in place for Kish Island, published in 2005, and an earlier and slightly more detailed master-plan from 1998. Kish is now managed by the Kish Free Zone Organization which has commercial status, although it performs the functions of a municipality. The island is a tax-free zone and, unlike the rest of Iran, visas are not required. Interestingly, Iran’s attitudes to women’s dress, entertainment and art are also far more relaxed here than on the mainland.

The position that Kish has held within the Persian Gulf for millennia as an international trading post, and as a ‘bridge’ between Persia and Arabia, accords with its new ‘free-zone’ status and is reflected in its eclectic architectural identity. In 1973 the Shah of Iran decided to create a royal resort at Kish, and the long curving beach on the east coast was chosen as the best location. A family of fashionable modern buildings were built between Ferdousi Street and the sea, including villas, palaces, hotels and the now disused casino (see Plate 23). There are also two pre-existing settlements on Kish Island: the first, the aforementioned ‘city centre’ is along the northern half of the east coast, and the other is the town of Safein up in the north-west corner. A local map reveals that the west side of Safein is older than the rest. ‘Yes, that’s where the locals live’, says Ibrahim our driver. He tells us that the oldest houses there are 45, or maybe 50, years old.

THE NORTH COAST

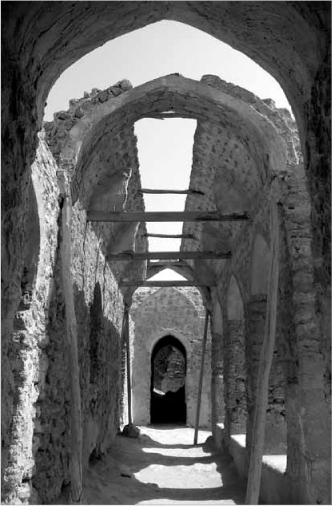

Before cycling around the island, or before looking in detail at the ‘city centre’ area or the beach or the new residential neighbourhoods, we decided to use the car to look around to find the roots of Kish. Is there something which makes Kish uniquely the way it is, something which defines its identity? The ruins of Harireh, on the northern coast, between Safein and the ‘city centre’, are mostly still unexcavated. However, there are still some significant things to see here. A fortified house, a bath-house and the ancient port have each been dug out and reconstructed, while work on the old Seljuq Mosque is also now underway. A thousand years ago, Harireh was one of the Gulf’s most important centres of pearl diving, fishing and trading. The fortified house is a gem; a small courtyard with simple pointed arcades is surrounded by a set of vaulted rooms. Its simplicity and solidity and the charm of its curved lines makes a lasting impression. The port is a memorable piece of engineering. Built hard against the 3 m-high cliff edge, a natural quayside is created. Vertical loading bays have been cut into the rock, allowing for goods to be lifted from smaller boats at the lower level, which is tucked in under the overhanging cliff.

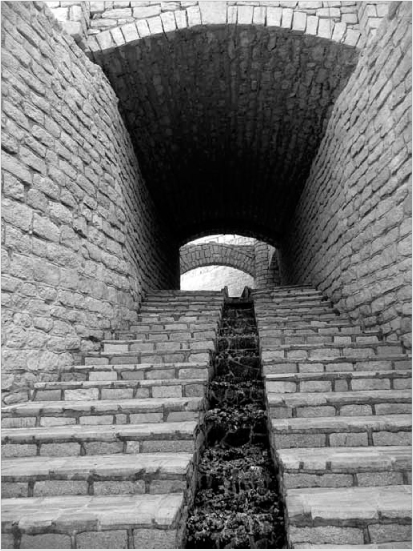

We then moved on, past the historic walled garden of the Sezham, to the nearby Kariz, one of the most extraordinary ancient water systems in the world. A network of tunnels, 3 km in length, was carved deep underground over 1,000 years ago. Sweet water was collected from aquifers beneath the island, thereby providing all the water the island needed for centuries (water is today piped from a desalination plant on a nearby island). The Kariz is a beautiful place, especially the tree-filled open cut where the tunnels meet and a sweeping ramp gives access up to ground level. The enterprising owner of the Kariz has renovated the tunnels and made this into a tourist attraction with a café and small shop at the bottom. However, it is easy to imagine even more use being made of this amazing place. It would make a unique venue for art exhibitions or marketplaces – food for thought perhaps for those who want to raise the profile of Kish as an international tourist destination.

14.6 The old fortified house at Harireh

14.7 Ruins of Harireh port with new Damoon rising on the horizon

14.8 The ancient Kariz water system

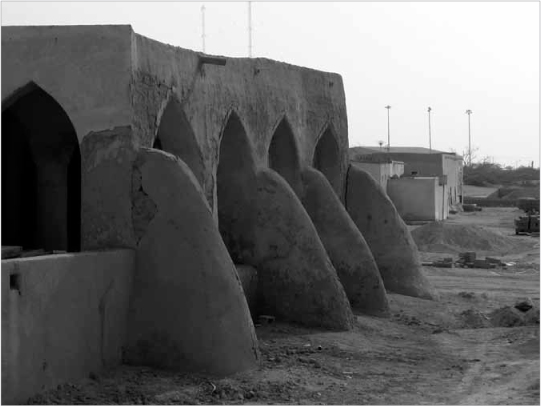

14.9 Wind-towers on the reconstructed Ab Ambar well on Kish Island, Iran

From the Kariz, I could see five wind-towers (badgirs) rising above the trees. They serve to cool the Ab Ambar, which is a reconstruction of a traditional domed well with two huge water drums served by galleries and accessed by a long staircase cut into the ground (see Plate 24). The badgir is of course one of the great inventions of Persian architecture and is now to be found all around the Gulf region. The cruciform flue catches the wind whatever its direction and the opposite flue creates negative pressure, sucking air naturally through the building. The projecting beams were used to hang wet sheets on so as to cool the incoming air by evaporation.

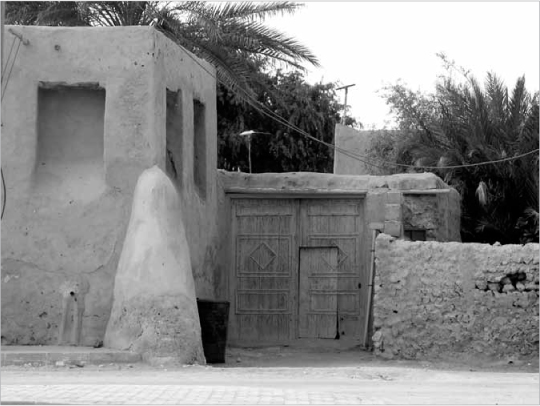

A little further along the coast we arrived at Safein (pronounced safeen, from the Arabic word for ‘ship’). Despite its Persian associations, this is clearly a traditional Arab village. Its character is evidence that Gulf regional identity and the Arab Culture are as strong as local identity in other countries which surround the Persian Gulf. Although this village is poor, it is rich in terms of the original thick-walled, mud-built, single-storey houses which are also to be found in varying forms all over the Gulf. I quickly get the feeling that Ibrahim was wrong about these houses being only 45 years old. It is all too easy to imagine this place as a charming fishing village, well looked after and welcoming to tourists, but currently it seems to be sadly unloved. As we explore the narrow lanes and courtyards, certain architectural motifs can be seen again and again. The slightly ‘battered’ or sloping walls with upturned parapets, the massive conical corner buttresses (posht), the recessed panels at high level that were formerly slots to let in air and light but are now blocked up, the projecting marzam rain spouts, the elaborated doorways: all of these are designed elements, the product of both technology and aesthetics, developed over generations to make the harsh environment of this region habitable. Does this perhaps offer clues to the local identity and the architectural heart and soul of Kish Island?

14.10 Traditional house in Safein

The old mosque at the edge of Safein is run-down but as noted it is now being refurbished. It is a beautiful building, with an open arcade and huge buttresses on the seaward side. The crude refurbishment work involves cutting metal air-conditioning boxes into the walls, immediately adjacent to the original natural vents. Between the sea and the mosque a large new park is being built. It is clear that money is being spent on Safein. We are lucky enough to meet Mr Daryobar, who I am told is the ‘chief’ of Safein. He was coming out of the mosque beside the parade of shops which he owns, along with other properties here and a farm at Baghou (the only rural settlement on Kish). He invited us to his house that evening where we are regaled with stories. In the house’s special room for entertaining guests (majlis, or mihman khaneh), we sit around on floor cushions at the edge of the room while Mr Daryobar’s son brings sliced watermelon and fresh dates. The ‘chief’ continues:

14.11 Safein Mosque in 1980 before the new park was built

14.12 Mr Daryobar in conversation with the author

When they built New Safein, the eastern part of the village, they didn’t explain why. In 1978, when it was ready, the people from Mashe moved there and nine months later the Revolution happened.

I hadn’t heard about Mashe at all until then, but I was soon to learn that it had once been the main village of Kish Island, further along the coast.

They were not happy to begin with; some of the families had been there for 500 years. Many of them went elsewhere; to the mainland, to Kuwait or Dubai, but some came here … There are houses in Old Safein which are 300 years old. Just round the corner is Ali Ebrahimi’s house. He died at eighty and his father, who was 100 years old, said that his own grandfather had grown up in the same house.

At last we were beginning to find out the true value for Kish of these older buildings in Safein. So I asked Mr Daryobar if he was happy about the new park that is being built, even though it has moved the shoreline further away from Safein. He answered with a quote from the Koran: ‘You can predict that events will turn out badly but you cannot know what the outcome would have been if they hadn’t happened.’ He tells me he is happy about the park: ‘The President [Mahmoud Ahmadinejad] came last year and we asked him to help us renew Safein. He listened and arranged that work should be done.’ The Iranian government are now building a new fishing port on Kish too: ‘Families have been fishing here for centuries, as well as pearl diving, trading and farming.’ Many of these ancient sources of income have since ceased to be part of community life – trading is now carried out only on an industrial scale, and pearling stopped here in 1982 – but fishing is alive and well.

In a later discussion with Mr Shahandeh, I am shown the report on ‘New Ideas and Projects for Investment in Kish 2009’. From this I discover that the prospect of transforming Safein into a tourist attraction is more than a vague possibility. With a predicted budget sum of US$ 45 million, plus a construction period of three years and a period for capital return of five years, this is an ambitious development plan which runs the danger of ‘sanitising’ some of the gritty authenticity of Safein today. Having said that, something clearly has to be done to ensure the town’s future and, provided the local people can stay once it’s completed, this project should hugely enrich Kish Island as a whole. The sprawling modern neighbourhood of Mir Mohana, which now adjoins Safein, will likewise benefit from having a focal point of this sort.

Mr Daryobar is also not opposed to change: ‘If a bird comes, it stays a while and then leaves, but it brings good things. Time moves on.’ Most of the evening with him is spent hearing the story of how Kish was founded by Gheish, a man who was swept there by a great flood from the mountains of Persia. His descendants, living at Harireh about a thousand years ago, blinded a young female student whose eyesight was so good that she could spot a man on a camel, on the mainland, holding honey in one hand and oil in the other. In retribution for this terrible crime against the young woman, Allah destroyed Harireh and the island lay dormant for many centuries.

1973 AND ALL THAT

The previous evening I had met another of Kish’s old-timers, Mohammad Alavi, an architect who has been working in Kish Island since 1973. He is now refurbishing the low-rise Taban Hotel at the southern end of Ferdousi Street, just next to the 22-storey ‘Twin Towers’ project which is half-completed. He was involved right from the inception of the Shah’s masterplan to turn Kish into a royal resort. In working with the Californian landscape designers, EDAW (part of AECOM) and Mercury Architects from Tehran on that project, Alavi shares responsibility for a part of Kish’s legacy which is as significant as (and far more visible than) its older historic fabric.

One of the weak points of the master-plan drawn up for the Shah was its lack of any long-term vision. It didn’t anticipate the new centre for Kish becoming the substantial town that it now is, let alone a major city as it could be in future. Ferdousi Street was simply laid out as a feeder road to the line of hotels, villas and the casino, all backing onto the beach. This has contributed to a lack of urban identity and connection to the sea which the growing ‘city centre’ suffers from, although the EDAW design does have its inadvertent benefits too. The fact that there is no urban corniche in Kish is in fact one of its greatest assets, because it means those who are enjoying the sea can escape from the presence of cars. Meanwhile, priority has been given to a remarkable bicycle track which runs around almost the entire island.

As we found when looking into the archives held by the Free Zone Organization, a crucial part of the Shah’s masterplan – indeed its proposed ‘civic centre’ – was never implemented, presumably because of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. This ‘civic centre’ was intended to be situated at the angle between Ferdousi Street and Iran Street. In the style of its day, the scheme emphasised the 45-degree angle and set up a strong connection to the ‘prow’ of the island at the far north-eastern corner. Today it is a site which is still sitting vacant, waiting for a project called ‘The Flower of the East’ to take root, as will be mentioned again later. The primary building intended for the Shah’s ‘civic centre’, i.e. a mosque, was never built. Perhaps the lack of this public building and the emptiness of this important corner of the island accounts for much of the placelessness that the ‘city centre’ exudes in its present-day form.

14.13 Bicycle track at the main beach

At the southern end of the beach a steep outcrop of rock, now the site of the Dariush Grand Hotel, marks the division between the world of tourists and that of the old Shah’s winter palace. It is significant for the character of Kish that there is still no enclave for the super-rich to develop their mansions, and that the shoreline is fully accessible to the public, except at this one point. The original 1970s master-plan drawings revealed a James Bond-style fantasy of buildings with tectonic concrete fins and sloping walls. Indeed, almost all of the walls seemed to be sloped, either forwards or backwards, and as I progressively got to know Kish I realised that, whether I personally liked it or not, this kind of form is now as much a part of the island’s ‘vernacular’ as are the traditional houses in Safein.

Mr Alavi, who was of course a young man in 1973, attributes the design of many of the key buildings, including the casino, to David Hilliard of Mercury Architects. Perhaps, then, the slopes were meant as a contextual response to the sloped buttresses seen in Safein. To my eye, however, they spoke of fashion rather than timelessness. It is ironic in a way that buildings with this modernist motif are still being designed in Kish today, while the ‘timeless’ simplicity of traditional Gulf architecture is being ignored. Generally, with a few distinctive exceptions, the diagonals on the latest buildings slope back from the street, which has no logic in terms of casting shade or reducing solar gain. To their credit, however, balconies and deep façades are being commonly used to shade window openings. Overall, a sense of solidity prevails. There are not too many buildings of thin glass-and-metal in Kish, although I wonder if things can be kept that way.

14.14 Typical sloped-wall architecture in Kish’s ‘city centre’

My visit to the Free Zone Organization’s archive also provided the greatest shock of the trip. Looking at aerial photographs of Kish Island in 1967, I realised that the village of Mashe had been totally obliterated to create the Shah’s new resort. For me, this discovery revealed the 1973 master-plan to be one of the greatest acts of cultural vandalism I have known, and also one of the greatest mistakes in urban design and the commercial planning of a tourist resort. Mashe, according to Mr Daryobar, was in fact the lovelier of the two ancient villages on Kish Island. Its wanton destruction by the Shah echoed Allah’s attitude to Harireh a thousand years before, but with no good reason. To have refurbished Mashe and made it the heart of the new resort was exactly what was needed to give the Shah’s creation the sense of scale, character, urban grain and identity which the area so obviously lacks. It is ironic that if Kish’s main shortcoming is its sense of placelessness, the retention of Mashe would have been the answer. It is after all hardly a new discovery that the built heritage has value, both human and economic.

14.15 Map showing the old village of Mashe in 1967

One of Mr Alavi’s projects within the Shah’s 1970s master-plan was to design New Safein, which, although today it seems just as unloved as Old Safein, is impressive in its urban design. If we compare the plan of Old Safein – an organic plan of soft, ‘nearly rectangular’ geometries which is highly typical of the Gulf Region – with that of New Safein, they are obviously extremely different. Mr Alavi’s plan involved an arrangement of strict rectangular blocks but placed in a very irregular formation to achieve a remarkably similar effect. His buildings are so plain that one hardly knows how old they are, which is greatly to the architect’s credit. New Safein could become a very pleasant place once it has been renewed. The mosque in New Safein, also originally designed by Alavi, was remodelled after the 1979 Revolution to reflect the not-at-all-local architectural style of northern Iran and the Shi’a, as opposed to Sunni, form of Islam.

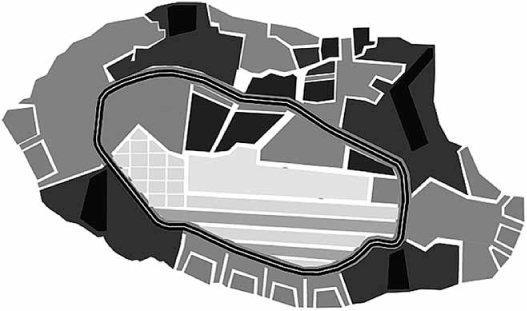

14.16 Urban plan showing the contrast between Old Safein on the left and New Safein on the right

THE BIKE TRACK

Mr Alavi kindly lent us his bicycles so that we could navigate the whole coastline of Kish Island without using a car. The eastern beach is pleasant but rather patchy – disconnected and unkempt. As we moved south, passing the Dariush Hotel and the former Shah’s palace, it is surprising how many derelict structures we found in this otherwise prime part of the island. It seems to be more attractive for landowners to develop virgin sites on the periphery of the ‘city centre’ than regenerate the existing building stock. If this is the case, they are running the risk of spoiling the whole ‘Kish experience’.

It was precisely at this point, as we were cycling towards the looming ‘Twin Towers’, when I realised that there is now no going back for Kish. The only way to save it from becoming just another resort of mediocre quality (or worse), and to enable it to realise its full potential, will be to encourage more development – but only high-quality development. Meanwhile, its greatest peril is that ongoing development of the wrong kind (as currently underway) will ruin it forever. There is thus nothing to be gained by regretting the loss of the ‘unspoilt’ natural environment in Kish. There is little point also in regretting the arrival of lumpy high-rise developments which are sprouting around the island. These too are here to stay. What is of value, however, is to look for the most positive future for new development in Kish; in other words, to think of how buildings and, more importantly, the public spaces between buildings, can achieve an appropriate character and have lasting quality.

South of the ‘Twin Towers’, there is currently not that much development going on, but yet again the land is not unspoilt. The landscape here is scarred by derelict holiday villas and remains of local infrastructure, so the only realistic answer is to carry on riding the tide of investment in Kish so that one can redevelop with a strategic emphasis on the sites which currently give the place an unfinished feel. We passed the Dolphin Park and the so-called ‘Coastal Village of the Persian Gulf’, now under construction, which is only the beginning of building up the southern edge of Kish Island. It appears part of an unstoppable process. The long open cycle path along the southern coast is a relief, even in the heat. Strangely the wind was in the opposite direction from the usual prevailing north-westerly, so we were pushed along like sailing ships. Open scrubland with some trees is broken by industrial infrastructure such as the gas plant. The coastline here is mostly of coral rock, undercut by the waves, interspersed with beaches; it’s the home of rare sea turtles. The rock is clearly being eroded but no-one seems too worried as it is happening very slowly.

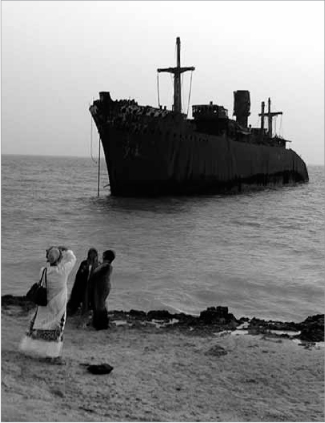

We continued past a derelict hospital – a venture in private healthcare which apparently folded within two years of opening – and moved on towards Keshti Younanie, which translates as the ‘Greek ship’. Strangely, along with the beach and the shopping malls and the heritage sites, this is one of Kish’s foremost tourist attractions. Most visitors to Kish take a taxi across the island just to be photographed there at sunset. Back in 1966, a Greek ship (which had in fact been built in 1943 in Glasgow) ran aground and it has been here, gradually decaying, ever since. It is indeed very memorable. Perhaps it is a clue to the eclectic spirit which is part of Kish’s character and could inform how it develops its ‘brand’ for the future.

14.17 The decaying Greek ship

Our cycle ride took us on through Safein and past Harireh to Damoon. The latest phase of development at Damoon is another high-rise hulk, also half-finished. Together with the ‘Twin Towers’ it acts as a ‘bookend’ for the coastline development on either side of the ‘city centre’. Judging from the hoardings, it looks as though these blocks might have been designed for any resort in the world, which makes me wonder, with these huge forms now emerging, whether the island is indeed ‘losing its shape’. However, looking to the future, when Kish will be developed to maximum capacity, it could be argued that these ‘bookends’ will be valuable orientation points. If only they were better designed! Regrettably, between Damoon and the ‘city centre’, our coastal path was broken by a large utilities compound and the industrial port. The fracturing of the northern edge of the ‘city centre’ is doubled by the vast (although currently empty) site for a new golf course, a key part of Kish’s future. It puts Damoon in an ambiguous position; is it part of the ‘city centre’ or is it in fact part of the separate northern strip, along with Safein and Mir Mohanna? I feel sure the answer is, or should be, the former. However the whole unfinished nature of this corner of the island requires resolution.

14.18 Damoon rising out of the ground

After the port we arrived at the 200-hectare wasteland being held in readiness for ‘The Flower of the East’ project. We were shown the design later that day – now, thankfully, put on hold for economic reasons. The project’s layout again reflects the strong 45-degree accent of the Shah’s original master-plan, but the new version would create a stronger presence on the seafront, plus it is more vulgar and at a much larger scale. Grandiose aspirations of this kind are not necessarily wrong; in fact, a bold development placed here could do a lot of good. However, making sure that its design is, firstly, of exceptional, international and lasting quality, and secondly, that it’s relevant and resonant for Kish – past, present and future – is essential if the island is to fulfil its potential. Achieving that aim with the current design would be impossible. Then, just as we finished our bike ride around the site of ‘The Flower of the East’, we found the old mosque of Mashe, the only remnant of a community so sadly lost. It is a small and beautiful building and is now being restored. But how can a project like ‘The Flower of the East’ ever be designed to embrace this kind of treasure in a meaningful, integrated way? How can the ‘grand project’ and this mosque be relevant to each other, and, more importantly, in what ways can ‘The Flower of the East’ offer a positive contribution to the future identity of Kish?

1989 TO 2005

Apart from Safein and Damoon, where do the people on Kish Island actually live? The 1998 master-plan laid out two new neighbourhoods, Mir Mohanna (adjoining Safein) and Sadaf, the latter which in effect forms the western edge of the ‘city centre’ area. These communities are both now fully established, with about 10,000 homes between them; they consist of a mixture of low-to-medium-rise houses and apartment buildings. Both have been developed in adherence to strict dimensional guidelines and although none of their architecture is better than mediocre, and the urban design fails to create a memorable environment, nonetheless they are at least urbanistically coherent. What is lacking however are effective connections to the ‘city centre’ or to Safein and the rest of the road network on Kish Island. A brand new inner-ring road with six lanes won’t help in this aim, even if it will certainly speed up further piecemeal development all around the island.

Sadaf is part of the extension of the ‘city centre’ which terminates in the site for the ‘The Flower of the East’ and the proposed golf course, at the centre of which area sits the recently completed Sadaf Tower. This latter building is surely a warning of the cultural demise of Kish over the next few decades unless the tide of poor design can be turned around. Sadaf Tower is a beacon of what Kish mustn’t do if it wants to fulfil its potential as a successful place for human habitation. If this building were on an ordinary site in Kish, then it would be unremarkable, since there are many others which are just as bad. However, the problem is that it just happens to sit on one of the most significant landmark sites in the whole topography of the island. The Sadaf Tower sits at a pivotal point between the ‘city centre’ and the northern coast, as well as between ‘The Flower of the East’ site and the airport. How could they have got it so wrong? The fact that it is ugly and characterless is more than just a missed opportunity; it sets a general tone of blandness and will do lasting damage to the development of Kish until it is replaced or at least re-modelled.

14.19 Typical street view in Mir Mohanna

14.20 Sadaf Tower

Looking more broadly at the role the imminent golf course will have within the urban plan, this too is problematic. Connection, orientation and legibility seem to be what are most needed to ‘stitch together’ the various areas of development on the island, yet the golf course forms more of a barrier than a connector. With this part of Kish still unfinished, the outcome cannot be judged as yet – but I would certainly recommend, given the poor quality of Sadaf Tower, that a serious review of the whole design for this area is needed before work restarts on it. In 2004, Drees and Sommer, a firm of German consultants, were commissioned to produce what Mr Shahande called ‘a destination master-plan’ – i.e. a close study of the existing economic, demographic and environmental conditions, as well as future opportunities for development. Residential trends formed a major part of their analysis, yet the main emphasis was on tourism. Given that a dramatic economic growth of 200 per cent is predicted from 2010–2025, and four times that figure in terms of the expansion of the international market on Kish Island, their proposal was not unreasonable in suggesting continued building in already partially developed areas and in open sites around the perimeter, while also keeping breaks in development along the southern coast to maintain some of its open character.

The resulting master-plan appropriately focussed on an enrichment of the ‘tourist offer’ such as sport, conference venues, nature and heritage. Strangely, neither Safein nor Mashe were even mentioned in the master-plan, nor was the Kariz, although opening up the Shah’s palace to the public, and creating a pearl museum, and eco-tourist ventures such as the transformation of Mr Daryobar’s farm at Baghou into a tourist attraction, were all proposed. In the more recently published ‘New Ideas and Projects’ document, there is also an ambitious plan for the Great Museum of Natural History and Fars Civilisation. This would be the most significant project of all for Kish to define its brand. Anything short of design excellence, however, would only damage its chances of becoming the exceptional place it could be in the future.

14.21 Urban master-plan by Drees and Sommer in 2004 for Kish Free Zone Organization, indicating the inner-ring road and main development areas

Just one page of the 2004 master-plan dealt in any detail with Kish’s streetscape and how it might be improved. The document correctly proposed the creation of stronger built edges along Ferdousi Street. However, to ensure that an environment of lasting quality is delivered, a far subtler and more detailed master-plan is required. This should be called the ‘quality master-plan’, both in the sense of defining the relationships between buildings and public spaces, and in promoting an architectural vernacular for Kish that embodies greater harmony and identity. The 2004 master-plan for Kish Island, meanwhile, is now being branded by Iran as the ‘Persian Garden of the Persian Gulf’, and although its illustrative drawings are weak, the underlying idea is profound. By making the connection between the Persian root of the word ‘paradise’ and the man-made idea of the garden, the concept points towards the fact that the design quality of the man-made environment offers the key to the future of Kish.

SO WHAT IS NEXT?

As I take stock of the speed at which Kish Island is changing, and the degree to which it is currently undermining the best aspects of its own character, I find myself wondering what is needed to turn the tide without stopping its development flow, and, should that be possible, which is the best direction for it to go? Let’s assume, in the simplest terms, that lasting prosperity, based primarily on long-term success in tourism, is the overriding priority for Kish’s future. Currently, since Kish is part of Iran, then the financial model at work here – in terms of catchment area and influence – is going to be more national than global. However, given the Kish Free Zone Organization’s international orientation, and its need to compete so as to avoid falling behind other holiday destinations around the Persian Gulf, then Kish’s ambition must surely be to increase its global profile as well as its appeal within Iran. How can it do this? Quite simply by making itself into a uniquely memorable, comfortable and delightful place which people will want to come back to year after year – in other words, a real ‘Earthly Paradise’. And what might the ingredients be for such a place? In my view, there are four key aspects, which I will now summarise in turn.

Firstly, there is a need for a strong, local cultural identity, particularly in terms of architecture and landscape; it has to be a physical environment which is quintessentially pleasant and harmonious while also being distinctive – in other words, not just a copy of other successful resorts in the Persian Gulf such as Dubai. To this end, a unique local vernacular – indeed a common architectural language – needs to be identified and fostered. A ‘base beat’ for the built environment is needed; a cohesive backdrop to endow Kish with a strength of character that it currently lacks.

So what, then, is the natural vernacular of Kish? I would argue that it’s a combination of several themes, old and new, local and international. Reluctantly, maybe, I would acknowledge that a significant part of the local vernacular is the ‘sloped wall’ modernist concrete style of the 1970s, originating as it did from the United States. This is to be found all over Kish and, whether one likes it or not, it has become part of the local identity. For a style that was so particular to the 1970s, it is extraordinary how many buildings, some under construction today, still adopt it. Far more significant for me, however, are the traditional buildings of Safein and, formerly, Mashe. These simple, solid vernacular structures have intrinsic value and should be treasured in their own right. But they also have great value as clues for achieving contemporary, contextual design of Kish’s unique and distinctive character and its lasting relevance.

A contemporary vernacular therefore needs to reinterpret traditional forms, rather than simply mimicking them. The traditional architecture of the Gulf region has evolved out of structural and environmental challenges, and the availability of particular building materials. Universal solutions were thus refined by particular local influences. To achieve an authentic vernacular, a subtle technical design process is needed, one which can learn from the past but look to the future in dealing with the increasing challenges of global climate change. There will be technical and aesthetic aspects to creating this link between the past and the future. For example, the use of thick walls, shading structures and natural ventilation enhanced by wind-catchers should all be re-assessed in the light of 21st-century technology. The proportions of traditional buildings, their massing and window openings, their special features such as entrances and screens, should be analysed and reflected in contemporary design. The very simplicity of the traditional buildings lends itself well to timeless reinterpretation.

While the traditions of Kish are both local and regional, its aspirations are becoming increasingly international. Indeed its traditional architecture has much in common with other parts of the Gulf region, both Persian and Arabian. So how can any modern vernacular be unique to Kish? It needs to include references to distinctive details from the island – decoded and assimilated in a contemporary way – which can be part of consistent design guidance and ongoing dialogue between designers, developers and statutory authorities. If this is achieved, then universal responses can be made particular. The search for a strong vernacular is not a search for homogeneity. Instead, it is a search for a common language. As with any spoken language, accents will differ and a pleasing level of diversity can still be achieved. Design guidance to promote such a language would touch on topics such as form, composition, surface and detail. It may also be the case that, as with Amman in Jordan or Muscat in Oman, tighter building controls should be imposed on the use of materials, so as to promote cohesion.

The second key ingredient that I would mention is the public realm – that is, the roads, pavements, landscapes and, importantly, building edges. A more detailed master-plan is needed to accompany architectural guidelines that dictate how buildings, particularly within the ‘city centre’ of Kish, should meet with the streets to achieve clarity, vitality, coherence the prioritisation of giving positive form to the spaces between buildings. This revised master-plan should also highlight every opportunity to develop any currently under-used plots. Tax advantages should be offered to promote buildings on these sites. In my view, Kish could double its density without any new virgin land needing to be developed, and, as long as excellence in pursued in design, the island would be the far better for it. The urban environment would be stronger in character whilst the natural environment could be preserved.

As well as defining codes for new development sites – in terms of massing, street frontage, architectural character, connections and transport – the new detailed master-plan should also make specific proposals for landscape treatment across the island. It should include ways of giving greater priority to pedestrians and cyclists, along with techniques of creating shade for them as they walk or cycle. Simple moves (such as resurfacing every road in a natural ‘bound gravel’, rather than black tarmac) would be powerful ways of enhancing the identity and feeling of Kish Island. If there is a financial cost to be born here, aside from the fact that such moves would more than pay direct dividends in terms of attracting visitors, then it would be reasonable to tax each new development with the requirement for a ‘landscape contribution’ to pay for such physical enhancements (on the same basis that a ‘Section 106 agreement’ requires developers to do so in the UK). A trip up and down Ferdousi Street is enough to show how the pedestrian environment could be improved by the intensification of development. New lines could be set for building frontages, reducing street widths and introducing arcades for shading, and parking could be reallocated to the rear of buildings. Through such measures, a significant increase in density, value, environmental quality and urban character could be realised.

The third ingredient would be to adorn Kish Island, over time, with a series of exceptional landmark projects. Focal points are needed both to attract and delight people, as well as to define the Kish’s future identity. Current projects of strategic importance to the island, such as ‘The Flower of the East’, would however need to be radically redesigned to ensure that they are of international quality and carry a resonance with local cultural traditions. Other projects in the pipeline, such as the proposed Great Museum at Harireh, should be procured through a global design competition, and should become the first in a new era of leading architectural patronage on the island. Kish could make itself world famous for exceptional design. As a parallel, the town of Columbus, Indiana in the USA was made famous as the ‘town of architecture’ after the Cummins Engine Company developed a policy of subsidising the best up-and-coming young American architects for every new building in the town. The company’s chairman bore the additional costs of architects’ fees personally in exchange for the right to control the quality of design, and Columbus has reaped the benefits ever since. Kish should do the same.

Landmark projects in energy and environment are also needed on Kish Island, such as a large-scale solar power plant in the centre of the island (which could potentially be a tourist attraction in its own right). Solar-powered initiatives such as electric transport vehicles would then follow, and become part of the positive identity of Kish as a place to live and a resort to remember. Landscape projects should also be required to have landmark status – including tree-planting on a grand scale, innovative approaches to irrigation, perhaps resulting in the actual creation of the ‘Persian Garden of the Persian Gulf’. How might all this be achieved? I suggest that a Design Council ought to be established for the island, combining local and international expertise, with the aims of promoting development in accordance with the revised master-plan and of procuring excellence in design. This body should meet regularly to review and approve development proposals and to push forward strategic initiatives. The quality and continuity of the ongoing dialogue and shared vision between developers, designers and the Free Zone Organization would be, above all, a crucial component in securing an authentic, coherent and characterful built environment for Kish in the longer term. Indeed, Kish Island, with its free-zone status, could act as a ‘pilot project’ for Iran to revive its global reputation as a leading centre of culture.

The fourth ingredient for creating the ‘Earthly Paradise’ would be a programme of high-profile festivals and events which could set Kish apart from its competitors, creating an annual cycle of activity across the island, potentially with links to universities or other cultural institutions. Initiatives such as an international art fair, or a film festival such as happens at Kassel or Cannes, or a regatta of historic sailing ships as at Klapeida in Lithuania, would draw in specific visitors at different times of the year. High-profile names could then be invited to lead these Kish festivals: for example, the cellist, Yo Yo Ma, with his musical ensemble, the Silk Road Project, and who specialise in the fusion of eastern and western musical traditions, might establish an annual musical event. Festivals of this sort could thus become part of the cultural mapping of the Island, with different events in different locations, such as the Kariz, the ‘Greek Ship’, Harireh and Mashe. In this way, a strategy for events could influence and be influenced by the place-making strategy that is integral to the revised master-plan. On top of this, local events such as monthly markets ought to be established, plus there is also potential to raise the profile of leisure and sport-related events along with international conferences.

In conclusion, the crucial question is why should Kish aspire to be anything other than the usual high-quality holiday resort? Simply, because tourism is now Kish’s raison d’etre– as it has been for decades – and this means by definition that it has to compete in the global marketplace. Tourism always thrives best on good design and the creation of remarkable memories; in other words, those memories which shine out from the ordinary ones, and hence memories that really last. To be memorable, a place must be distinctive, and when one looks at the character of most resorts around the Gulf region, so often unremarkable, it is easy to see how Kish could set itself apart. But it is also easy to see how it could fail. There is nothing wrong in the fact that Kish Island is changing so quickly. Much of the groundwork that has been done there is good. However, if Kish really wants to turn itself into an ‘Earthly Paradise’, then it needs to change direction and push urban, architectural and landscape design right to the top of its agenda.