Kuwait City, Kuwait

This chapter explores the urban identity of Kuwait City in light of the proto-globalised architectural figure of Frank Lloyd Wright and his mythical projects in and around the Persian Gulf. It might seem curious to use Wright’s influence within the Gulf region as a starting point, but as this chapter will show, he was someone who claimed to respect the architecture of the region even if he often muddled his way between Arabian and Persian precedents. For instance, in his 1937 book, Architecture and Modern Life, he mused: ‘the opulent Arab wandered, striking his splendid, gorgeous tents to roam elsewhere. He learned much from the Persian; the Hindu, learning from the same origins.’1 In addition, Wright frequently quoted his admiration for The Arabian Nights tales, and indeed within Wright’s home in Oak Park, Chicago there was an illustration from ‘The Fisherman and the Genii’ in his children’s playroom. Wright was so captivated by these tales that he identified himself as ‘the young Aladdin’ in An Autobiography.2 Wright therefore equated his own powers of creativity with Aladdin’s, and the idea of the rubbing of the lamp became a symbolic expression of his imagination.3 So when Wright was invited to Iraq to design an Opera House for Baghdad in January 1957, it was his chance to prove, unequivocally, his creative genius. The brief for the Opera House was typically inflated by Wright into the need for a much grander ‘Cultural Quarter’ for the city – an unrealisable personal fantasy, but also prophetic of the fantastical projects and the search for cultural identity currently being undertaken on a lavish scale within the Gulf States.

As is well known, Kuwait has experienced a remarkable growth since the Second World War due to its natural oil wealth; indeed, the country changed beyond all recognition from the original settlement dependent on sea trading and pearl fishing. Kuwait City serves as its capital and by far the largest urban conglomeration, possessing in 2012 an estimated 2.38 million people in its metropolitan area (around 90 per cent of the total population). Only a half of the population are Kuwaitis, although most of the non-resident workers come from other Arabic countries and so the ethnic divisions are not as noticeable as in, say, the United Arab Emirates. In this chapter, a brief historical overview will first provide a regional context that considers the influence of Islam, globalising European empires, and post-colonial nation building. Questions will be raised about ‘orientalist’ perceptions of the region as captured in a number of colonial literary texts that portrayed an imagined and exotic Middle East. The mechanisms for planning rapid urbanisation that were adopted in Kuwait will then be discussed and local reactions considered. The relationship between place, culture and architecture within the domain of globalisation will be at the heart of the discussion throughout.

3.1 Postcard of Kuwait City

The later text in this chapter is organised around a number of taxi journeys to specific sites which provided me with a narrative about Kuwait and Frank Lloyd Wright’s influence. My research involved conversations with academics, residents and expatriate immigrants alike; I also collected souvenirs and wrote postcards home, and visited sites in the city centre and in the peripheral suburbs. The act of journeying has long been an inherent part of inspiring and constructing architecture, and in this spirit I will reflect upon my own experience and Wright’s recollections. My observations can only be preliminary and speculative, yet they shed a different view to the contemporary bombastic architecture in so many cities on the western coastline of the Persian Gulf.

THE ARABIAN PENINSULA

Situated at the centre of the region named the Middle East by Eurocentric nations, the Arabian Peninsula was the home of several ancient civilisations and trading routes that helped to foster early global encounters. Lying to the north, the cities of Mesopotamia and Babylon were part of the ‘fertile crescent’ that linked the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea, and there was evidence of an advanced Mesopotamian civilisation on Failaka Island, near Kuwait, around 3,000 BC.4 The Arabian race as such were first noted in 850 BC by Assyrian writers, who described them as a ‘nomadic people of the North Arabian desert’; these were of the Adnanais stock, whilst there was also another fairly settled grouping called the Qahtanis to the south and west of the peninsula.5 Alexander the Great famously expanded his Greek Empire eastwards during the 3rd century BC, establishing a fortress on Failaka. The Romans later took command of the whole region at the start of the 1st century AD, and they remained dominant over the next three centuries, protecting their pre-modern trade route – the ‘Silk Route’ – which linked Asia and Europe. The Roman Empire was succeeded in turn by Byzantine and Persian dynasties, with the latter of course predominating on the eastern side of the Persian Gulf.

The Prophet Mohammed was born in 570 or 571 AD in Mecca, and as a result, the peninsula came to have a lasting religious and cultural impact on the surrounding region, and globally. The Prophet established the Islamic faith, which Muslims believe to be ‘the ultimate faith, which completes and perfects the two other heavenly religions – Judaism and Christianity’.6 Islam propagated quickly and by the time of his death in 636 AD, the Prophet Mohammed ‘had succeeded in welding the scatter and idolatrous tribes of the peninsula into one nation worshiping a single, all-powerful god’.7 Thereafter, various caliphates expanded the Islamic faith, and by 711 AD its dominance extended from Spain to Persia. Grube identifies two general concepts that epitomise Islamic architecture: a concentration on the design of interior space, and the absence of specific forms for specific functions.8 He notes, consequently, that ‘Islamic architecture is given to hiding its principal features behind an unrevealing exterior.’9

Similarly, a number of scholars have identified the internal spatial concentration within Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture, especially in his non-residential designs, most of which was derived from Japanese architecture.10 However, Wright also at times used thick enveloping masonry walls to separate occupants from the city, and to define the internal spaces, and in this regard there are obvious spatial similarities to traditional Islamic architecture – even if Wright never acknowledged any such link. Nonetheless, when reflecting on past ages of architecture, Wright plotted a history of masonry construction in which he expressed his admiration for the ‘low, heavy, stone dome’11 found in Byzantine architecture, and in particular the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.12 He proceeded to note that in ‘the domed buildings of Persia we see the Byzantine arch still at work’.13 What pleased Wright so much was that these domes managed to resist their outward thrust without the need for concealed chains or a corniced ring beam. He remarked approvingly that their ‘masonry dome was erected as an organic part of the whole structure’.14

Defeat at the hands of the Crusaders in the 11th century, and later attack from Mongols to the east in the 13th century, made Arabians withdraw into a period of comparative ‘retreat and isolation’.15 However, another great Muslim empire, this time founded by Turkish warrior princes, was begun in the 13th century and conquered the last remnants of the Byzantine Empire before proceeding to annex Persia and the coastal Arabian states. For Arabians, the four centuries of Ottoman rule were doubly disappointing, since they had lost their status as rulers of the Islamic world and Arabic culture was no longer seen as dominant.16

A number of ‘orientalist’ narratives emerged during the 19th century as European empires sought to justify their own expansionist agenda in the Middle East. As noted by Edensor, ‘the exotic remains tethered to those consistent themes that emerged under colonial conditions, an imagined, alluring non-Western alterity embodied in styles of clothing, music, dance, art, architecture, and food.’17 This confrontation between western and Ottoman cultures propagated the supposed ‘otherness’ of the region, with Sir Richard Burton being a prototypical example of a colonial adventurer whose roles included those of ‘explorer, spy, linguist, sexologist, translator and a writer.’18 In addition, Burton was responsible for translating and compiling The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights, thereby transplanting into the minds of millions of children (such as Frank Lloyd Wright) the mythical world of Aladdin and his Genie. Other colonial writers such as Gustav Flaubert contributed to the exotic perception of the region; nowadays he would be regarded as a predatory sex tourist. T. E. Lawrence originally set out as an archaeologist to survey a number of Crusader castles in the region, but his mapping and linguistic skills made him an ideal British spy and leader of the Arab counter-insurgency against the Ottoman Empire in 1916–1918. Again the colonial script of Seven Pillars of Wisdom and Revolt in the Desert was the basis for Lawrence of Arabia (1962), a later iconic film that only embellished the myth.19 Finally, Wilfred Thesiger travelled extensively in the Empty Quarter of the Arabia Pensinsula, documenting the vanishing life of the Bedouins in his book, Arabian Sands (1959); in doing so, he confronted the colonial legacy that was increasingly commodifying the region by recording the traditional everyday activities of desert dwellers.

There was also a sense of ‘orientalism’ within western architectural culture. Frampton identifies the importance of The Grammar of Ornament (1856) by Owen Jones in disseminating ‘other’ cultures to a wider audience of aesthetic thinkers and producers. The book was hence a ‘transcultural, imperialist sweep through the world of ornament demonstrated by implication the relative inferiority of the European/Greco-Roman/medieval legacy compared with the riches of the Orient’.20 Furthermore, there was a link from Owen Jones to Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright as Celtic ‘outsiders’ who ‘searched for an “other” culture with which to overcome the spiritual bankruptcy of the West’, given that it was commonly believed that Celtic art had originated in the Middle East.21 According to Frampton, Sullivan and Wright shared an ‘implicit theology of their work … a conscious fusion of nature and culture’.22 He noted that ‘in Islamic architecture, the written, the woven, and the tectonically inscribed are frequently fused together’, and indeed Wright’s work sought such an integrated ideal.23 Frampton concludes by claiming that Wright’s ‘text-tile tectonic’ was to reach its pinnacle in the layout of Broadacre City, ‘an infinite “oriental rug” as a cross-cultural, ecological tapestry writ large, as an oriental paradise garden combined with the Cartesian grid of the occident.’24

KUWAIT’S BACKGROUND

Despite the importance of Failaka Island in the history of the Persian Gulf, it is known that Kuwait City – which sits opposite Failaka on the mainland – developed separately and also much later on. Its name was derived from the Arabic for ‘a small fort’.25 In 1756, a Danish explorer reported that Kuwait City had 10,000 inhabitants ‘who live on the produce of peals and fishing’, with a fleet of 800 sailing boats.26 By the late-18th century the British were active as maritime invaders keen to protecting their emerging Indian interests, focussing on trade with Basra in southern Iraq. In 1859, Kuwait had signed a pact with the Ottoman Empire, but were somewhat wary of the latter’s power; thus in 1899 it signed a new treaty with Britain which gave greater protection to Kuwait’s sea trade.

The defeat in the First World War of Germany and fellow Axis powers led to the break-up of the already declining Ottoman Empire. Mansfield identifies two contrary trends in the following years among Arabs: on the one hand, there was desire to develop a sense of territorial nationalism to support the countries newly freed from Ottoman rule, and on the other a contrasting demand for ethnic ‘protection and unity’, particularly in light of the emerging Zionist movement in Palestine.27 Whilst Kuwait’s borders were already fairly defined and strongly supported by Britain by this point, its newer neighbours tended to consist of amalgamations of different tribes and alliances within national borders which had simply never existed previously. These new nations – Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia – had been engineered largely by the British Empire as an attempt to dilute Arab influence, a solution which unsurprisingly has not led to long-term peace in the region. As early as 1920, Kuwait came under attack from neighbouring tribes, requiring the building of a new city wall to control the access to its capital from the west. There have been three successive Gulf conflicts rooted in the contradictory aspirations of separate national identity and the concept of a pan-Arabic state. Kuwait has suffered badly in all three conflicts, being occupied by Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces in 1990–1991 under the premise of creating a wider Ba’athist Arabic movement.28 A coalition of forces led by ‘Pax America’ liberated Kuwait, and, conveniently for the western powers, managed to restore the agreed boundaries and the all-important distribution of oil reserves.

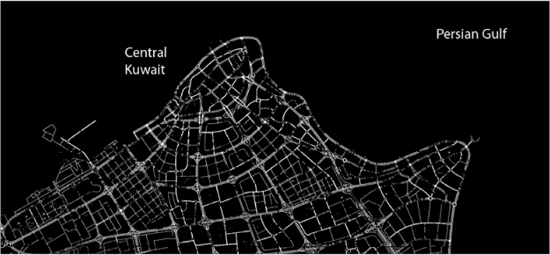

Oil had been first discovered in Kuwait in 1934, but it was not commercially extracted until after the Second World War. Kuwait City had hitherto been an excellent example of an integrated desert settlement with a protective outer wall, an organically ordered town plan formed by layers of accretion, close-knit low-rise buildings with narrow lanes, and a visibly democratic city of generally no higher than two-storey structures. However, by 1950 Kuwait City’s population had leapt to 150,000, of which almost a half were now immigrant workers, and traffic congestion was becoming acute. This led the Kuwaiti government in 1951 to commission Minoprio, Spencely and Macfarlane to prepare a master-plan. This new vision for Kuwait City was based on the British New Town precedent, with a comprehensive road network, clear zoning for different uses, and a protective ‘green belt’. The British firm had recently completed the plan for Crawley in West Sussex, with Minoprio admitting: ‘We didn’t know anything much about the Muslim world and the Kuwaitis wanted … a new city.’29 Gardiner noted that the proposal ‘was primarily a road plan – [which] arose from the five gateways of the wall.’30 Or as Jamal wrote acidly in the Architects’ Journal in 1973, this first master-plan ‘was simply the imposition of western technology onto an established Arab society’.31

Kuwait City gained independence along with the rest of the country in 1961, and its urban growth continued; by 1970 the population had soared to 733,000, of which only 47 per cent were Kuwaiti. A second master-plan was commissioned, this time from another British practice, Colin Buchanan and Partners.32 However, neither the design process nor the resulting master-plan proved at all successful, given that indigenous Kuwaiti architects and planners were by now beginning to question the wisdom of bringing in foreign consultants. The debate highlighted a growing sense of cultural confrontation. In the same Architects’ Journal article, when discussing the second master-plan, Jamal identified the major flaws in western thinking about urbanisation in the Persian Gulf:

‘Rapid urban growth resulting from implementation of the plan will speed up material changes in the society without compatible cultural change. Traditional Kuwaiti character will not be reflected in the new urban and physical environment, while the traditional environment will deteriorate further … Generally speaking, Kuwait should not assume that economic growth equals, or automatically brings, personal social happiness. The Kuwaitis’ way of life should not be geared to consumption or wasteful living as seen in the West.33

Colin Buchanan’s firm published a subsequent rebuttal in the Architects’ Journal in May 1974.34 However, a third article on the subject in the same magazine, published in October 1974, dismissed their master-plan as a failure. It noted that ‘all copies of the plan have been lying locked up … for the past three years’ on the grounds that it couldn’t be understood, approved or thus implemented by Kuwait City’s planning authority.35 Additional master-plans were prepared by western consultants in 1977 and 1983, and then by the Kuwait Municipality itself in 1993. The most recent master-plan, drawn up in 2003, was produced in collaboration between the Kuwait Engineering Group and Colin Buchanan and Partners.36 Despite all these official efforts towards planning, however, the destruction of the old building fabric in Kuwait City simply continued – and hence the passionate cry for cultural reflection by Jamal in the mid-1970s was never heeded.

ARRIVAL

Using the internet I had booked a room at the Ghani Palace Hotel by Saleh Al Mutawa, which opened in 2002 (see Plate 3). The hotel is modelled on a conventional Yemeni town house, with whitewashed walls, insets of coloured glass, intricately detailed timber screens and balconies, and projecting timber joists and water spouts. Inside, the hotel’s thin atrium made allusion to a traditional alleyway, with an open arcade of shops and projecting balconies giving another Arabic cultural representation. A local expert, Yasser Mahgoub, told me that Al Mutawa’s work embodies ‘Kuwaiti traditional architecture in his buildings’, while also pointing out that of course such forms are also part of a wider Arabic consciousness.37 From my hotel room on the sixth floor, I could see Kuwait City in its confrontation with the Persian Gulf – albeit with a six-lane motorway mediating the connection as a legacy of a city re-designed for the highway.

After a short rest, I met with Omar Kattab at the University of Kuwait in the afternoon, and we discussed a number of ideas concerning Frank Lloyd Wright. It seems that although Wright’s projects for (adjacent) Iraq and Iran are well known within the Gulf region, there isn’t any record of him ever visiting Kuwait, or having designed anything in the city. Undeterred, we went for a drive towards the city centre, progressing down one of the main radial thoroughfares. At one set of traffic lights, we paused to view the impressive neo-capitalist skyline of tower blocks gleaming against the blue sky. Kostof argues that the skyline acts as the ‘shorthand of urban identity … when the city centre ends up an aggregate of tall office buildings, we recognise that the city image has succumbed to the advertising urges of private enterprise.’38 Further on, we slowed down at Al Soor Street, the site of the former city wall, where a remnant from the 1920s fort now lies within a roundabout. The mythical ‘green belt’ of the 1950s Minoprio master-plan was in reality a strip of desert, with little planting or shade, just a memory of the old lost town.

3.2 Ghani Palace Hotel (2002) by Saleh Al Mutawa

3.3 Interior atrium of the Ghani Palace Hotel

3.4 Sketch map of the road network of Kuwait City

3.5 View of the skyline of Kuwait City

3.6 View of remnant of old fort wall on Al Soor Street

IDENTITY

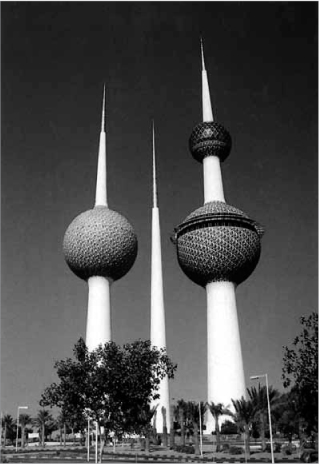

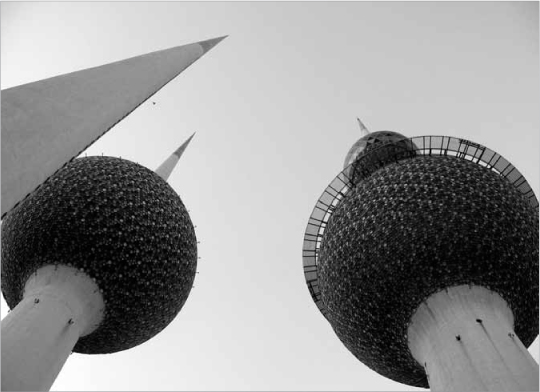

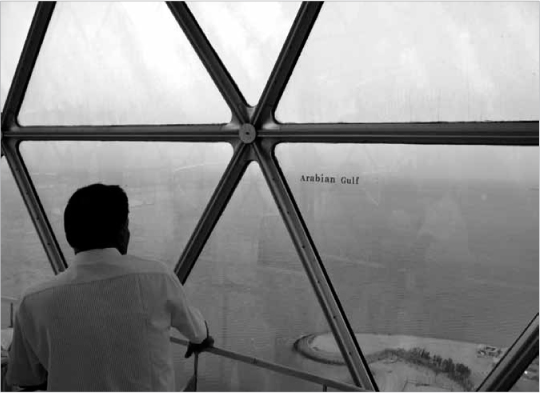

In the evening I caught a taxi to the northern edge of Kuwait to visit the Water Towers, completed in 1979. I travelled along the Arabian Gulf Road and experienced the two identities of Kuwait, the dusty oil-rich commercial city to the south and the hazy blue waters of the Persian Gulf to the north. I was impressed by the futuristic design of the Water Towers. It is claimed that the design was inspired by an Arab perfume burner with a long tall neck and spherical reservoir for its base; this seems a plausible enough connection, and now it would seem that perfume burners are being made in the image of Kuwait Towers! It is also a design that clearly fulfils the role of international icon, and yet is immensely practical. At 180m in height the observation tower was the tallest structure in the Gulf region for several decades after its completion in 1977. Kultermann has commented on this progression from architectural function to cultural expression: ‘the water towers in … Kuwait … are significant signs of a shift from technology and its dominating negative impact on the human environment towards a positive use for necessities, entertainment and beautification.’39 I entered the larger of the two towers and got into a golden lift carriage which took me up 120m to the observation level, which was entirely glazed within a triangulated space frame. From this level I could see the whole of Kuwait City and much of the Persian Gulf beyond. It was twilight and city was now illuminated by its tall office towers. Being the festival of Ramadan, the fading light also brought respite for residents from the day’s fast, and at 82m I too found a welcoming restaurant serving a hot buffet. Predictably, most of the diners were well-dressed Kuwaitis whilst most of the servants were Indian or Filipino.

3.7 Kuwait Water Towers (1979) by VVB, a Swedish engineering company

Gardiner identified an ‘architectural plan’ for Kuwait City from the 1960s that was jointly directed by two architects: the Englishman, Leslie Martin, and the Italian, Franco Albini.40 Essentially they wished to give the city a stronger architectural identity, and so they asked four internationally-known architectural practices to analyse the existing city plan and work up designs for specific case studies. Together, they summarised their key architectural principles under five points: maintaining the waterfront as a recreational area; turning the area around the Seif Palace into a special historical site; reintroducing residential areas to the city; preserving and expanding the traditional souks and bazaars; and maintaining the old city wall as a ‘green belt’ zone.41 The design by Alison and Peter Smithson for the Kuwait Government Buildings was a poetic vision and also critique of the new architecture within the city and the Persian Gulf generally. They proposed instead an open urban fabric based on a gridded ‘mat’ that was orientated towards existing mosques, low buildings and overhanging roofs to provide shade for pedestrians beneath.42 The dramatic rise in oil prices after the 1973–1974 ‘Oil Crisis’ boosted Kuwait’s income further, allowing a number of the case studies to be progressed – but not sadly the Smithson’s rather intimate proposal.

3.8 Viewing platform in the Kuwait Water Towers

Frank Lloyd Wright’s unbuilt project for a ‘Cultural Quarter’ in Baghdad (1957–1959) represented a singular vision for the identity of that city. Although had been invited with other modernist ‘masters’ to participate in Baghdad’s development, Wright assumed the mantle of cultural arbiter as his original brief for an Opera House turned into a full-blown Arabian myth. When introducing his scheme in a 1957 issue of Architectural Forum, Wright proclaimed ‘that a great culture deserves not only an architecture of its time, but of its own’.43 Rhetorically he cited the ancient cities of Mesopotamia and Babylon, the original Garden of Eden, the circular ‘City of Peace’ by al-Mansur, and the imaginary court of Harun ar-Rashid in The Arabian Nights. No doubt these cultural references pleased the regime of King Faysal II, a Hashemite ruler who was not even an Iraqi. The centrepiece of the ‘Cultural Quarter’ was to be the Grand Opera and Civic Auditorium; it was based on the intersection of two circles, one for a revolving stage and other for an auditorium with 1,600 seats to hold an opera performance, or an additional 3,700 seats for ‘conventions or patriotic celebrations’.44 Wright designed a symbolically expressive crescent-arch to support the proscenium, which was then to be ‘decorated with metal-sculptured scenes from A Thousand and One Nights’.45 And at roof level, directly above the centre of the auditorium was to be the figure of ‘Aladdin [Wright] and his wonderful lamp’.

3.9 Crescent Opera House for Baghdad by Frank Lloyd Wright (1957–1959)

The modern-day implications of Wright’s form-making are not too hard to spot. In the Gulf State of Abu Dhabi, part of the United Arab Emirates, the Saadiyat Island scheme attempts to create a ‘cultural quarter’ for the 21st century with four contemporary masters of the architectural universe: Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, Tadao Ando and Zaha Hadid. Interestingly, Hadid was born in Baghdad, and she was charged with producing a new Performing Arts Centre in Abu Dhabi as another expression of western culture – Arabian states seemingly can’t get enough opera! Hadid says that her Performing Arts Centre’s ‘organic design will have five theatres, a music hall, opera house, drama theatre and a flexible theatre with a combined seating capacity of 6,300.’46 Furthermore, she explains the concept as ‘a growing organism that sprouts a network of successive branches … [and] performance spaces, which spring from the structure like fruits on a vine.’47 However, as Charles Jencks commented on the Baghdad project: ‘Wright loses control of his geometry and allows it to contradict function, material, construction, structure, freedom [and] … organic architecture.’48 Likewise the gratuitous form-making of Hadid may be considered sensual and ‘organically’ inspired, but it also lacks functional and material integrity. For Wright, his ‘Cultural Quarter’ was intended as a continuation of imagined cities from the past, whereas Hadid’s scheme engages with one city’s aspirations for the future.

I took a short walk along Arabian Gulf Street at the end of the day, with the heat now gradually waning, to take a closer look at the impressive National Assembly Building (1978–1982), by the esteemed Danish architect, Jorn Utzon (see Plate 4). Kuwait did not dream of chimerical opera houses but rather built a National Assembly to project a progressive and democratic identity for the country and the region. Historically, an informal means of democracy had existed alongside the ruling Kuwaiti family of Al Sabah, with the local merchant class forming a ‘majlis, or advisory council’ to discuss affairs of state.49 But this delicate balance or power was altered significantly once oil revenue began to be directed solely through the Emir and his ruling family. Consequently, a quasi-welfarist model was established in the 1950s to try to redistribute some of the oil wealth by building new schools and improving the infrastructure. As noted earlier, this process only caused resentment among Kuwaitis, and so they demanded greater participation in government as a reaffirmation of their national identity.50 Kuwait duly became independent in 1961, with the Emir as a constitutional monarch, thus establishing a paternalistic ruling dynasty since copied in other Gulf States. In 1962, Kuwait’s first elections were held for its 50 seat National Assembly, which was charged with checking legislation proposed by the Prime Minister. However, this ‘democratic’ Assembly has had fitful existence, having been disbanded by the Emir on a number of occasions.

Utzon’s design for the National Assembly sought to reflect a number of Arabic features, and yet Vale notes a number of contradictions, For example; is the bold sweeping entry canopy just a simplistic western reference to an Arabic tent?51 Or is it a subtle acknowledgement of the Emir’s Bedouin past? But then again, tents are transitory elements, usually black or brown in colour, not a ponderous white concrete construction.52 Yet within the National Assembly, gradual change has been achieved: in 2005 women were allowed to vote; in 2006 the roles of Crown Prince and Prime Minister were separated; and in 2009 the first three women Members of Parliament were elected. The voting base has expanded, but even so only about 10 per cent of Kuwait’s population of c.3.5 million is allowed to vote. The recent ‘Arab Spring’ resulted in a number of demonstrations with some calling for a new Prime Minister, although not a change of regime, and Bedouins called for improved rights.53 The protests were appeased by legislators who promised to look again at civil rights, so seemingly democracy does function within Kuwait.

3.10 National Assembly Building (1978–1982) by Jorn Utzon

3.11 Seif Palace, Kuwait City

Interestingly, Utzon’s original design for the National Assembly Building had a mosque placed beside the main entry, thus giving the sweeping entrance canopy far more relevance as a place of congregation. But now the reconceived ‘Bedouin tent’ is merely a ‘monumental carport … [where] leaders meet their chauffeurs.’54 Just a short walk along the Arabian Gulf Road are the Seif Palace, Foreign Ministry, Grand Mosque and Stock Exchange. The old Seif Palace was built in the early years of the 20th century with a striking neo-Arabic watch tower, and its neighbouring replacement looks a rather fascinating low structure with abundant Islamic surface decoration, although I couldn’t get to see much further, since it was as heavily fortified as other public institutions here. It is disappointing that these state buildings are so detached from each other and from ordinary Kuwaitis. Any future uprising in Kuwait would need to reclaim the road, a symbol of the city, and a means of divide-and-rule. When I got to the Foreign Ministry, however, the guards outside were preparing a small feast because the sun was now setting, and they kindly offered me to join them for a drink. So I shared some Vimto and dates, and we chatted briefly, but since my Arabic is not that good, my observations were mostly restricted to the climate – i.e. complaining that I found it very hot. They wanted to know where I came from and whether I liked Kuwait, before asking: ‘Do you like Muslims?’55 It was a rather personal enquiry, but one that reflects an ongoing sense of tension between western countries and the Middle East.

BEYOND THE CITY CENTRE

The next day I met with Yasser Mahgoub, who works at Kuwait University, at the classically inspired Central Mall which sits next to the Ghani Palace Hotel. We then drove together to the Tareq Rajab Museum, passing a number of water towers along the 5th Circular Road: the towers were designed as giant representations of palm trees, often grouped together as if to form an oasis. It is a brilliant idea for retaining water, creating a genuine architectural presence in their conception and scale, and I was thrilled to see them next to the roadside. Gardiner has claimed that there is a passing reference to Wright’s dendriform (tree-like) columns in the Johnson Wax Administration Building, which is true enough – except that Wright’s columns had pin joints at their base and so would topple over in Kuwait!56 The basement museum is located in the Jabriya district, on Street 5/Block 12, and we got lost for a short time whilst negotiating that suburb. We discussed Wright’s legacy as we walked around the museum, and I asked about why his appeal in the Gulf region seems so strong

3.12 View from car of suburban dwellings in Kuwait City

Gwyn Lloyd Jones: Do you think that the planning outside the city centre here, with its dispersed motorised suburbs, bears any relation to Wright’s Broadacre City?

Yasser Mahgoub: No, not at all; here the city planning was based on the Garden City typology, and not Broadacre. But I think that the Mile High Tower by Wright was a concept that has caught on in the Gulf with the Burj Dubai [Khalifa], and now there is a 1001-metre tower proposed for the new Silk City scheme [across the bay from Kuwait City]. The size of that tower is inspired by the 1001 Tales from the Arabian Nights.

3.13 Tareq Rajab Museum

Gwyn Lloyd Jones: That’s really fascinating. Wright talked a great deal about The Arabian Nights while doing his Baghdad project, so there is clearly a link.57

Most of the suburban villas that I passed belonged to Kuwaiti nationals, as only they are allowed to own property. The houses displayed a number of styles: Arabic, classical Palladian, quasi-modernist. Given that the inspiration for expanding Kuwait City was Britain’s post-war New Towns, with their car-based principles – as Fraser shows, heavily influenced by America – then it is this model which can be seen all around.58 Kuwait’s capital was developed as a typical ‘City on the Highway’ possessing all of the ‘four main foundations’ for a motorised suburb: new roads to open up more land, zoned land uses, government-provided mortgages, and a population boom.59 Wright often eulogised the virtues of America’s road network, declaring that ‘along these grand roads as through veins and arteries comes and goes the throng of building and living in the Broadacre City of the Twentieth Century.’60 His vision for Broadacre was based on a decentralised mode of settlement that was part-prophetic and part-trend planning of the kind which already existed in Los Angeles in the 1920s and 1930s. As such, it represented a particularly American viewpoint about travel, democracy, freedom, and architecture’s role within all those things. Wright proclaimed that the city of the future could be ‘everywhere and nowhere’61 – and I would contend that Kuwait is now similarly affected by possessing a suburban condition lacking any identity specific to its geographical location or environmental conditions.

Frank Lloyd Wright is also undoubtedly prophetic of the present desire to build ever-taller towers. As Yasser Mahgoub had told me, some developers in Kuwait have for a few years now been planning a 1001-metre-high tower – designed by another American architect, Eric Kuhne – while in Saudi Arabia a genuine Mile High Tower is apparently being proposed on the Red Sea, near to the city of Jeddah. Not far away in Dubai, the Burj Khalifa Tower already stands at over 820m tall, the ultimate expression to date of global identity branding. It too was designed by a global American architectural practice, SOM, built by migrant labourers from poor emerging nations, and constructed in the Middle East for offices and apartments that may well be occupied by a multitude of nationalities. It’s a contemporary Tower of Babel built on sand! Having the world’s tallest building carries a certain status that Dubai obviously craves, but what else does the tower tell us about architectural identity? The Burj Khalifa is certainly similar to Wright’s own scheme for a Mile High Tower (1956), with its triangulated plan, diminishing mass and stepped profile. It is said that Wright’s initial brief had been to design a television antennae, but that he had developed it into a tower that could contain ‘all Illinois state government offices and consolidate commercial, governmental, and civic functions’.62 Furthermore, Wright claimed it ‘would mop up what now remains of urbanism to leave us free to do Broadacre’.63 I would suggest that the tower was a typical Wright edifice, although pushed to what to him must have seemed like the ultimate dimension of one mile, and it was conceived more for its imagery then its function. Interestingly enough, the novelist A.S. Byatt writes that ‘… the Thousand and One Nights is itself a symbol of infinity … the addition of the extra ‘one’ to the round thousand … suggests a way to mathematical infinity.’64 Yet again the links between Wright and Aladdin seem rather close.

3.14 Mile-High Tower by Frank Lloyd Wright (1956)

ALADDIN’S HOMECOMING

In the evening, Salmiya was busy with shoppers and a young crowd of Kuwaitis relaxing in the coffee shops, as a 21st-century diwaniya (gathering). It offered me a chance to reflect on my investigation into the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright. Kuwait has proven to be a resilient and progressive force within the Persian Gulf region, yet its precarious geo-political situation seems to dwell on its psyche – it appears to be a city on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Contrary to Wright’s views, I would advocate that the disjointed city centre needs to be reclaimed through infill spaces that connect better to one another and to the Gulf coastline; no doubt Wright would have advocated instead a relentless suburban existence into the desert. Kuwait’s discreet and egalitarian development should continue to be its focus, with wider reforms to embrace its enlarged population.

My own short trip to Kuwait and then along the western coast of the Persian Gulf has itself helped to contribute to the myth of Frank Lloyd Wright within a part of the world where he attempted to secure his legacy with a truly fantastical vision for Baghdad. As Frampton observes, there was a universal tendency in Wright’s work, and he definitely did not adapt his architecture to engage with different environments. Instead, the failed scheme for an Opera House in Baghdad was realised in Arizona, making the latter Aladdin’s second home! Yet, Wright’s idea for developing cultural identity through architecture was prophetic of what is now being undertaken in the Persian Gulf. The mythical paradise based on an idealised Broadacre suburb has possibly reached its ultimate conclusion with the Palm Jumeirah in Dubai, but that reality is an exclusive society not a democratic one. And the technological and financial commitment to build a Mile High Tower is now only being bandied around the oil-and-gas-rich Persian Gulf. But it would be a purely symbolic edifice and its function would be secondary: the ultimate myth of eternity.

NOTES

1 Frank Lloyd Wright, as quoted in Bruce Pfeiffer (ed.), The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright: Critical Writings on Architecture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 283.

2 Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (London: Faber and Faber, 1945), p. 38.

3 Donald W. Hoppen, The Seven Ages of Frank Lloyd Wright (Santa Barbara, CA: Carpa Press, 1993), p. 43.

4 Ronald Lewcock & Zahra Freeth, Traditional Architecture in Kuwait and the Northern Gulf (London: Art and Archaeology Research Papers, 1978), p. 12.

5 Peter Mansfield, A History of the Middle East (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 6.

6 Ibid., p. 13.

7 Ibid., p. 14.

8 Ernst Grube & George Michell, Architecture of the Islamic World: its History and Social Meaning (London: Thames & Hudson, 1978), pp. 10–13.

9 Ibid., pp. 12–13.

10 Jonathan Lipman’s chapter in Robert McCarter (ed.), On and By Frank Lloyd Wright: A Primer of Architectural Principles (London: Phaidon, 2005), pp. 264–285; Kevin Nute, Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan (London: Chapman Hall, 1993), pp. 40–41.

11 Quoted in Pfeiffer (ed.), The Essential Frank Lloyd Wright, p. 282.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Mansfield, A History of the Middle East, p. 21.

16 Ibid., p. 26.

17 Tim Edensor’s chapter in Joan Ockman & Salomon Frausto (eds), Architourism: Authentic, Escapist, Exotic and Spectacular (Munich: Prestel, 2005), p. 98.

18 Author profile in Richard Burton, To the Holy Shrines (London: Penguin, 1853/2007), p. i.

19 David Lean, Lawrence of Arabia (London: Horizon Pictures, 1962).

20 Kenneth Frampton’s chapter in Ockman & Frausto (eds), Architourism, p. 173.

21 Ibid., p. 174.

22 Ibid., p. 176.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid., p. 189.

25 Lewcock & Freeth, Traditional Architecture in Kuwait, p. 12.

26 Ibid.

27 Mansfield, A History of the Middle East, p. 229.

28 Ibid., pp. 229–230.

29 Stephen Gardiner, Kuwait: The Making of a City (London: Longman, 1983), p. 35.

30 Ibid., p. 37.

31 Karim Jamal, ‘Kuwait: A Salutary Tale’, The Architects’ Journal, vol. 158, no. 50 (12 December 1973): 1453.

32 Ibid., 1454.

33 Ibid., 1456.

34 Colin Buchanan, ‘Planning: Kuwait’, The Architects’ Journal, vol. 159, no. 21 (22 May 1974): 1131–1132.

35 Ghazi Sultan, ‘Kuwait’, The Architects’ Journal, vol. 160, no. 40 (2 October 1974): 792–794.

36 Yasser Mahgoub, ‘Globalization and the built environment in Kuwait’, Habitat International, vol. 28, no. 5 (2004): 509.

37 Ibid., 514.

38 Spiro Kostof, The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings through History (London: Thames & Hudson, 1991), p. 296.

39 Udo Kultermann, ‘Water for Arabia’, Domus, no. 595 (June 1976): 6.

40 Gardiner, Kuwait, p. 67.

41 ‘Proposals for Restructuring Kuwait’, Architectural Review, vol. 156, no. 931 (September 1974): 180–181.

42 Ibid., 183–190.

43 Anon., ‘Wright to Design Baghdad Opera’, Architectural Forum, vol. 106, no. 3 (March 1957): 89.

44 Ibid., 93.

45 Ibid.

46 Francesco Poli, ‘The museums of the island of happiness: Saadiyat Island, Abu Dhabi’, special issue on ‘Performing Museums’, Lotus, no. 134 (May 2008): 6.

47 Ibid.

48 Charles Jencks, Modern Movements in Architecture (London: Penguin, 1973/85), p. 137.

49 Rosemary Said Zahlan, The Making of the Modern Gulf States: Kuwair, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman (2nd Edition) (Reading: Garner Publishing, 1989/98), p. 34.

50 Ibid., pp. 42–44.

51 Lawrence Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992), p. 224.

52 Ibid.

53 Mark Tran, ‘Arab League states: a recent history of protests’, The Guardian website, 22 March 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/22/arab-league-states (accessed 27 October 2011).

54 Vale, Architecture, Power and National Identity, p. 231.

55 Conversation between author and guards outside the Foreign Ministry, Kuwait City, 20 September 2009.

56 Gardiner, Kuwait, p. 88.

57 Yasser Mahgoub, interview with the author in the Tareq Rajab Museum, Kuwait City, 18 September 2009.

58 Murray Fraser (with Joe Kerr), Architecture and the ‘Special Relationship’: The American Influence on Post-war British Architecture (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), pp. 148–183; see also Gardiner, Kuwait, p. 37.

59 Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), p. 316.

60 Frank Lloyd Wright, ‘Disappearing City’ (1932), in Bruce Pfeiffer (ed.), The Collected Writings of Frank Lloyd Wright: Vol. 2, 1930–1932 (New York: Rizzoli, 1992), p. 94.

61 Ibid., p. 85.

62 ‘Frank Lloyd Wright: Selected Projects, Mile High Tower’, Bilbao Guggenheim website, http://www.guggenheimbilbao.es/microsites/frank_lloyd_wright/secciones/frank_lloyd_wright/proyectos_seleccionados/torre_oficinas_mile_high.php?idioma=en (accessed 10 November 2009).

63 Frank Lloyd Wright, as quoted in Brendan Gill, Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright (London: Heinemann, 1988), p. 477.

64 A.S. Byatt (Dame Antonia Susan Duffy), The Arabian Nights: Tales from a Thousand and One Nights (New York: Modern Library, 2001), p. xiii.