5

MADE IN USAGE

Architecture in Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel

Caroline Dionne

Man stands out [from other living beings] in both respects – in the construction of social practice, and in being given to pure knowledge, seeing and thinking. He is the creature who has the logos: he has language, he has distance from the things that immediately press upon him, he is free to choose what is good and to know what is true – and he can even laugh.

Hans-Georg Gadamer1

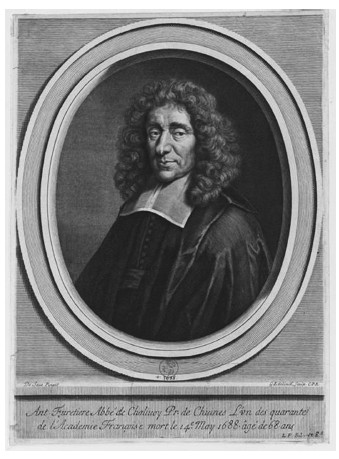

In the opening pages of Le roman bourgeois, seventeenth-century writer Antoine Furetière (Figure 5.1) concisely sketches the appropriate architectural backdrop for his narrative, a tale involving several “authentic” bourgeois characters of the Parisian context of his time.2 The author’s aim is emphatically stated: the setting of his novel shall be mobile, travelling through several neighborhoods of the city. He also wants it to be as truthful as possible and chooses Place Maubert, “the most bourgeois square in Paris”, as the initial location.3 But, Furetière insists, he will not engage in architectural description.

The book opens with a rather elaborate preterition through which Furetière announces his intention not to provide descriptive accounts of architecture. A common figure of speech, the preterition works as follows: a speaker feigns to avoid a certain topic while nonetheless mentioning it. For example, a political candidate could use the preterition as follows: “I will not speak here about my opponent’s extramarital affairs.” Through this rhetorical device, a sensitive topic is simultaneously occulted from conversation and brought into focus. In the case of Furetière’s tale, and consistent with a literary approach that has been referred to as antiromanesque, the trope partakes to the satire, producing the comical effect sought: it is primarily used to make the reader laugh. But the rhetorical stratagem serves other, less obvert purposes: it reinforces the realistic quality of the author’s narrated account while mocking, and criticizing, the grandiloquent and exaggerated tone found in seventeenth century French romances.4

Figure 5.1 Antoine Furetière, engraving by Gérard Edelinck ca. 1688. In Antoine Furetière, Dictionaire universel, contenant generalement tous les mots françois tant vieux que modernes, & les termes de toutes les sciences et des arts, … (A La Haye etc: Chez Arnout & Reinier Leers, 1690)

Furtière’s non-description thus unfolds over several pages through which the architectural locations meant to house the narrative – the main edifices, squares or neighborhoods – are mentioned by name but never described. Furthermore, in order to make even clearer his point that literary architectural description is highly problematic, Furetière mimicks what a fictitious (or at least unidentified) writer would have written. In a passage concerning a key location for the unfolding of the tale, the Parisian Church of Saint-Joseph des Carmes, Furtière writes: “A less sincere author, in his attempt to bring architecture into play and produce grand effect, could very well take the liberty of replacing the actual church with a description of a famous Greek temple.”5 Such ill-informed process – replacing a modern building with the description of an ancient one, changing the shape of a public square or altering the elements and proportions of a building’s facade – Furetière insists, would cause unwanted harm to the field of architecture, and, we may deduce, to the reader’s sensibility.

Furetière’s satire of a hypothetical counterpart – the figure of the insincere writer – is meant to strengthen his own position: he chooses not to depict an idealized, embellished and most importantly untruthful version of the architectural space of the bourgeoisie. Unlike this other writer who “may well fill his descriptions with words such as metopes, triglyphes, volutes, stylobates, and other unknown terms found in the texts of a Vitruvius or a Vignola to claim expertise in the field of architecture,” Furetière will refrain from interjecting architectural descriptions with words that he deems unintelligible to the reader.6 The author of Le roman bourgeois does not wish to aggrandize the architectural backdrop for his tale, nor will he distort or disguise its design. Contrariwise, in order for the context of the narrative to become tangible for the reader, Furetière primarily relies on the latter’s actual experience of the locations and edifices mentioned, as they exist in reality, in and around the city of Paris. In addition, the reader is invited to summon his own aptitude for imagination and build more elaborate architectural settings at will: “ I will not tell you how the church is, although it is rather famous. Those who so desire can go see it, or else build it in their imagination as they shall please.”7 The sole fact of naming a given location is, for Furetière, sufficient to trigger the reader’s imagination and set the action into its proper setting. The spatiality of Furetière’s narrative thus almost entirely rests on the reader’s pre-existing experience of architecture.

The lengthy passage ends with Furetière nevertheless revealing something about the church of the Carmes: “I will only mention that it isthe center of the bourgeoisie, and that it is highly attended because of the license to speak that this place provides.”8 The architectural merit of the building, central to the unfolding of the first part of Furetière’s novel, is therefore tied to the role and potential of architecture to frame the interactions of the Parisian bourgeoisie and, most importantly, to foster voluble social gatherings. Architectural space can be summoned and, ultimately, play a role in literary fiction, as the locus of social gathering and conversation.

Furetière’s reliance on the readers’ pre-existing experience of architecture and faculty for imagination implies that the kind of architectural knowledge readily accessible through everyday experience prevails over object-oriented description. This knowledge formation relies, as we shall see, on usage understood as a collective mode of production of spaces and words. In that sense, Furetière’s use of the preterition at the beginning of Le roman bourgeois may be understood to serve another purpose: it underlines and problematizes the relationship of architectural knowledge – and of all knowledge – to words, to language.9 Furetière’s treatment of architectural description as this highly sensitive topic, as this subject matter not to be mentioned but nonetheless brought forth, begs the question of the importance of architecture in his wider system of knowledge, a position that we will attempt to reveal by examining his lexicographical work.

Furetière’s language-as-lived

The question of knowledge – of universal knowledge – is central to Furetière’s entire corpus. Clearly stated in the author/bookseller’s warning to the reader that precedes Le roman bourgeois, the purpose of his literary production is not only to entertain, as the subtitle of the book “A Comical Work” would suggest, but, essentially, to educate.10 In this case, education is achieved by providing the reader with the widest possible collection of moral and intellectual attributes, staged in exchanges of words (in conversation but also through accounts of transacted written documents). According to Furetière, indecent or ridiculous actions, unveiled through the specific obliqueness proper to the satire, bear the potential to summon their opposite – morally proper and elevated deeds – thus providing the reader with a universal account of human morality that may guide him towards ethical action and the acquisition of a farther reaching knowledge.11 The novel shall thus educate in the utmost vital field of ethics, and guide the conduct of one’s life with others.

Naturally, it is therefore in questions pertaining to language, understood as the foundation of social life, that Furetière’s intent to educate, to provide a general, universal understanding of things, found its most fertile ground.12 Furetière’s Dictionnaire universel, contenant généralement tous les mots françois, tant vieux que modernes, et les termes de toutes les sciences et des arts was published posthumously in 1690, under the protection of a foreign prince. The lexicographer had died a few years earlier, after dedicating the last fifteen years of his life to a meticulous process of compilation of the French language.

Furetière’s understanding of language and classification conflicted with that of many of his contemporaries: he partook actively in the famous Quarrel of the dictionaries, overtly attacking several members of the French Academy for their position regarding the French language.13 For those members of the Academy, a proper French dictionary was meant to account first and foremost for the elevated language spoken at court. The purpose of the Academicians’ compendium was thus to fix and formalize the limits of the “beautiful language” of the aristocracy that had, for them, reached its apogee: its scope was essentially prescriptive and grammatical.14

Furetière exposed his understanding of language at length in his Factums, a series of leaflets written and self-published over the years to defend his position against the Academy.15 There, in contrast with the academicians’ views, he posits language as an open, evolving arrangement. For him, the French language of his time, like all languages, cannot be systematized and restricted to a fixed – aristocratic – whole. In Furetière’s view, languages are given shape progressively, and undergo constant change.16 Consequently, the process of ordering a given language implied in the lexicographic endeavor is bound to account for this capricious quality, begging the following question: how can the dictionary, as a finite selection of words and definitions, be productive of true, universal knowledge?

The answer may lie in part with Furetière’s enfranchisement of the general public, understood as both beholder and maker of language. Further exposing his view, Furetière writes: “any given language always primarily belongs to those who speak it, that is, to the general public.”17 He then adds: “These books [dictionaries] are not meant to fabricate words, but to account for, and explain their usage”18 Hence, Furetière’s task in compiling the dictionary entries is to account for the widest possible levels of discourse, modes of speaking, and for the entire spectrum of words in use, understood as crucial accounts of the language’s vitality.

The Dictionnaire defines the word “usage” as “exercise or habit.”19 Furetière adds: “Several sciences and many arts are better learned through usage, through practice, than through theory.”20 To “use,” to “exercise” or to “habituate oneself” are thus crucial to the formation of scientific and artistic knowledge.21 As we shall see, this process-oriented type of knowledge formation bears a foundational character in Furetière’s understanding of universal knowledge.

Architectural knowledge in the Dictionnaire universel

As attested by its extended title, Furetière’s Dictionnaire gives specific importance to scientific and artistic terminology: it includes the widest possible collection of terms pertaining to all sciences and mechanical arts, to the production of artifacts, inventions and machines, as well as to the definition of their corresponding trades. It is notably Furetière’s insistence on including such terminology in his dictionary project that led to the famous dispute where he opposed several members of the French Academy. Despite the harsh consequences tied to his views – his eviction for the Academy, the loss of his royal protection and position at court – Furetière unceasingly sustained the necessity to include these definitions in his compendium.

Furetière favored a simple structure for his dictionary: words appear one after the other in an unbroken flow, organized alphabetically according to their first letter, much like in the case of today’s lexicons. The reader enters the book at any given point, following a specific query. From there, a system of cross-references may allow one to travel from word to word, moving across the book’s scope. This structure implies that words pertaining to the arts and sciences are not grouped thematically, but scattered through the entire compilation, seen by Furetière as binding elements. Terms belonging to astronomy, medicine, geometry or architecture sit next to each other and to day-to-day words, from the most vulgar to the utmost polite. It is in part this interweaving, conjoined with the active participation of the reader, that contributes, in Furetière’s view, to a fertile production of knowledge. As stated in the Factums, Furetière’s lexicographic process is, unlike the Academicians’, primarily guided by epistemological, philosophical concerns. All scientific and artistic terms, as well as words pertaining to the human trades, Furetière writes using an architectural analogy, “are the mortar that holds together the entire edifice of language.”22 Removing these words would prevent the reader of the Dictionnaire to access a crucial type of knowledge, leaving him with, to extend Furetière’s analogy, a pile of unbound stones.

In the vast realm of human knowledge accounted for through his encyclopedic endeavor, architecture is thus cited amongst the most important order-revealing fields of knowledge, after mathematics and geometry, between optics and pyrotechnics, along with what would today appear as esoteric or unscientific realms such as astrology, falconry or fishing (see Figure 5.2). In his definition of the architect, Furetière announces the scope of the trade: “One needs to know many things to be a good architect”23 The term “architecture” is first defined as the field of theoretical knowledge pertaining to building, “the art or science of building.”24 A second meaning follows: architecture is the means available to actually transcribe this theoretical knowledge into a work, that is, “the manner in which to build and the ornaments to use.”25 Furetière relies here on a comprehensive series of both ancient and modern architects and theoreticians and, much like in the Le roman bourgeois, the reader is invited to acquaint himself directly with existing works and treatises to form his own understanding of the field.26

Figure 5.2 Frontispiece of the 1690 edition of Antoine Furetière’s Dictionaire universel (Galica, Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

The definition provided for architecture ends with a third signification, tied to a substitute usage of the word and connected to how architecture is assessed, or received: “The term architecture is also used in regards to a building’s value, it can be attributed to parts of buildings, seldom to entire edifices.”27 This implies that not all architecture can qualify as good – or true – architecture but, more importantly, that assessment processes lay in the communality or popularity of a given expression – its accepted usage – as in, for instance: “The portal of the Louvre is a fine piece of architecture.”28

Like in the case of all definitions found in the Dictionnaire, Furetière appears to follow the principles of persuasive argumentation and presents the meanings of a given word according to three co-dependent levels of knowledge, akin to Aristotle’s tripartite division of science: the theoretical, the practical and the poïetic.29 The first signification points towards theoretical knowledge: it presents the logical or reasonable meaning of the word “architecture.” With the second level, Furetière ascertains the authority of his definition and secures his impartiality in the eye of the reader by relying heavily on the work of knowledgeable authors: the Dictionnaire radiates towards an extensive body of existing architectural treatises and buildings. Philibert de l’Orme’s famous Trompe at Anet, praised by Furetière for its awe-producing quality, “as it seems to be supported by nothing,” is but one example of how architecture can embody the practical knowledge of the architect, his cunning intelligence or know-how.30 Thirdly, Furetière’s means to account for the poïetic level of knowledge is to provide a colloquial expression, bringing forth an alternate usage of the word that invokes the reader’s personal experience, who most probably has heard or uttered the expression and seen the building in question.31 Usage can therefore be seen as a specific mode of knowledge formation. Albeit different in scope from the combined theoretical knowledge and practical know-how of the architect or, to borrow Alberto Pérez-Gómez terminology, his techne-poiesis, usage nevertheless participates to the production of architecture.32 Architecture is completed as it is being used.

Accordingly, it can be argued that the definition of architecture as a field of knowledge goes beyond the three previously mentioned significations given for the word. Its scope extends as the dictionary is used, that is, as the reader actively engages with the work and navigates between words. More than a hundred occurrences of the term “architecture” appear in Furetière dictionary, and definitions are provided for an extremely wide selection of architectural components, from “abaque” to “zoophore,” including the same “triglyphe,” “metope” and “stylobate” that Furetière had deemed unfitting to appear in Le roman bourgeois. An elaborate architectural terminology thus finds its voie royale in the Dictionnaire, precisely because once the terms are defined, used and understood by the general public, they may enter common usage and become crucial vehicles towards universal knowledge.

Usage, architecture and social life

For Furetière, the value of a scientific, artistic or literary work is assessed through the consent of the general public, an approbation that “shall be earned through pain and reason.”33 Not only is it good to obtain the public’s agreement in conjunction with the approbation of the Prince, but ultimately: “the origin of truth and the order of justice lay in the universality of the [public] vote.”34 In the early enlightenment context of the late seventeenth century, Furetière’s valuing of the judgment of the general public remains perplexing. If, for him, the vote of the public does not yet stand apart or overrule the consent of the King, it is nonetheless given explicit authority. Could this position announce the formation of a bourgeois public sphere or the development, in the legal and political context of the eighteenth century, of the notion of a public’s right?35

In light of our previous observations, we would nuance this claim. If Furetière’s general public is given a decisive power to rule, engaged in an active relationship with artistic, scientific or, in the case that interests us here, architectural production, this relation remains grounded, like all matters pertaining to human life, in language. Usage is defined through the social practice of space, as men converse and debate amongst each other. Furetière’s public’s vote is therefore cast collectively and indirectly: it is the expression of social life revealed through usage. In that sense, it does not yet represent the democratic voice of a fully formed political body.

From the structure, content and scope of the definitions provided in the Dictionnaire, we can infer that architecture, as an order-revealing form of knowledge, remains for Furetière contingent to the poetic making of its audience. As shown in Le roman bourgeois, the space of this encounter permeates the ordinary life of men: architectural knowledge is formed through everyday experience and good architecture fosters conversation.

Like in the case of all arts and sciences, the meaning of architecture can only be made effective through language, as it is being used, that is, ingrained with and embedded in conversations. Much like Furetière’s understanding of language as “alive,” architecture belongs to those who use it, as it is built collectively and progressively, from within. By positing usage as semantically creative, Furetière’s work reveals how architecture remains, in the late Renaissance, bound to epistemological questions and embedded in an everyday life governed by the polysemy of language, an architecture understood as the proper expression of social life and as the site of ethical choices made through conversation. This architecture is also the site of the satire, of unveiling the true by mimicking the false, and of understanding through laughter.

The final version of this paper was completed in the context of the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA) Visiting Scholars Program.

Notes

1 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Praise of Theory (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1998), 58.

2 Born in the very context of the bourgeoisie satirically exposed in Le roman bourgeois, Antoine Furetière (1619–1688) progressively ascended the social hierarchy. His practice as a writer was secured by obtaining the religious title of Abbey, a nomination in Richelieu’s recently founded French Academy and a royal privilege that led to the publication of a partial version of his future dictionary (Essais d’un dictionnaire universel, 1684). In the context of the Grand siècle, his literary works received limited attention. Furetière was, however, well known for his lexicographic production, and notably for his central participation in the Quarrel of the dictionaries. Extensive biographical accounts can be found in Alain Rey, Antoine Furetière: Un précurseur des Lumières sous Louis XIV (Paris: Libr. A. Fayard, 2006). I am grateful to Maarten Delbeke for first bringing Furetière to my attention and sharing his insight on the topic.

3 Antoine Furetière, Le roman bourgeois [1666], ed. Marine Roy-Garibal (Paris: GF Flammarion, 2001), 75.

4 Usually associated with twentieth century avant-garde literary movements, the antiromanesque approach finds its roots, as Ugo Dionne has pointedly shown, in much earlier literary practices. Dionne has stressed the ambiguous “modernity” of the seventeenth century antiroman, and more specifically how such an approach not only operates an internal critique of the genre itself but contributes to the historical development of the modern novel, playing in France a role analogous to that of Defoe, Fielding and Richardson in England. See Ugo Dionne,“Le paradoxe d’Hercule ou comment le roman vient aux antiromanciers.” Études françaises 42 (2009): 141–167. Marine Roy-Garibal has also stressed the experimental character of literary productions by Antoine Furetière, Charles Sorel and Paul Scarron in the context of the seventeenth century and emphasized their intent to convey a critique of the abundantly practiced and popular heroic romance of the time (especially those of Georges and Madeleine de Scudéry). Roy-Garibal also comments on Furetière’s use of to preterition as typical of the approach. Marine Roy-Garibal, “La crise du romanesque,” in Antoine Furetière, Le roman bourgeois [1666], ed. Marine Roy-Garibal (Paris: GF Flammarion, 2001), 350–351.

5 Furetière, Le roman bourgeois, 77.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., 78.

8 Ibid.

9 On the problematic relationship of knowledge to language, see Hans-Georg Gadamer, “Language and Understanding” (1970), Theory, Culture & Society 23 (2006): 13–27 and Truth and Method (London; New York: Continuum, 2004).

10 Furetière, Le roman bourgeois, 67.

11 Ibid., 67–70.

12 Processes of compilation permeate Furetière’s entire corpus and in this regard, Le roman bourgeois can be seen as a field of experimentation towards his lexicographic production. On this connection, see Marine Roy-Garibal, “Présentation” in Furetière, Le roman bourgeois, 49–56.

13 A detailed account of Furetière’s involvement in the Quarrel can be found in Alain Rey, Antoine Furetière, 83–126.

14 See François Ost, Furetière: la démocratisation de la langue, (Paris: Michalon, 2008), 49–56.

15 Trained as a jurist, Furetière’s main defensive strategy in regards to his dictionary project took the form of a series of Factum, in which the lexicographer engages his oratory skills to expose the facts in his defense and break his opponents’ argumentation. In the corpus of Furetière’s work, these form a third level of literary expression. See Antoine Furetière, Recueil des factums d’Antoine Furetière de l’Académie française: contre quelques-uns de cette Académie. Suivi des preuves et pieces historiques données dans l’édition de 1694 par CH. Asselineau (Paris: Poulet-Malassis et De Broise, 1858). Translations are mine.

16 Furetière, Recueil des factums, I, 16.

17 Ibid., I, 66.

18 Ibid., I, 10. Italics are mine.

19 Antoine Furetière, Dictionaire universel, contenant generalement tous les mots françois tant vieux que modernes, & les termes de toutes les sciences et des arts, … (A La Haye etc: Chez Arnout & Reinier Leers, 1690), 2155.

20 Ibid.

21 Furetière, Dictionaire universel, 1880.

22 Furetière, Recueil des factums I, 12–14.

23 Furetière, Dictionaire universel, 128.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 See Furetière, Dictionaire universel, 128.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Philippe Beck identifies several locations in Aristotle’s corpus where this firm distinction between three “forms” of science appears, notably in the Metaphysics, the Nicomachean Ethics and the Topics. See Philippe Beck, “Logiques de l’impossibilité” in Aristote, Poétique (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), 8.

30 See Furetière, Dictionaire universel, 2071.

31 The term poïetic, from the Greek poiesis, “to make” is found in both Plato and Aristotle. In Plato’s Symposium, poiesis is connected to love (by Agathon) and associated with man’s strive for immortality which takes three forms: (1) natural poiesis through sexual procreation, (2) poiesis in the city through the attainment of heroic fame and finally, and (3) poiesis in the soul through the cultivation of virtue and knowledge. The two latter seem central to Furetière’s understanding of usage. See Plato, Symposium 208c–d, 209c–d, in Selected Dialogues of Plato, trans. Benjamin Jowett (New York: Modern Library, 2001).

In Built upon Love, Pérez-Gómez shows how similar spatial intervals exist between “a work of architecture and the observer/participant and between the architect and his work of techne- poiesis,” and pointedly traces the historical origin of these intervals to “eros,” to love, to a mode of making connections between things driven by a longing for knowledge and wholeness. See Built ipon Love: Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics (Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press, 2006), 34.

32 On the relationship of theory to practice and the techno-poetic dimension of architectural making in the context of the late Renaissance, see Alberto Pérez-Gómez, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983), especially Chapters 5–7.

33 Furetière, Recueil des factums, I, 311.

34 Ibid., II, 48.

35 Jürgen Habermas has connected the appearance of a “bourgeois public sphere” in the context of the eighteenth century to specific spatial configurations that were not yet actively practiced in Furetière’s lifetime. See Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry Into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press, 1991). Also, closely examining Furetière’s production as a jurist, François Ost characterizes Furetière’s lexicographic approach as eminently modern and prefiguring the development, in the eighteenth century legal context, of the democratic notion of a public’s right. See Ost, Furetière.