Manama, Bahrain

Bahrain, a small island archipelago located in the heart of the Gulf, is often described as one of the most developed economies in the region. Along with Dubai, it certainly offers the only model as yet for post-oil economics amongst the Arab oil-producing states. With its oil resources about to dry up, Bahrain realised that it needed to invest in other economical activities to maintain and develop its progress. During the last decade, therefore, Bahrain has started to take major steps towards economic diversification, primarily by addressing the financial and tourist sectors. To emphasize the new reality of the Bahraini economy, and to highlight its altered identity as a post-oil country within the Gulf region, the Ministry of Oil was eradicated at the end of 2005. The search for a new identity for Bahrain and its capital city, Manama, has swiftly encouraged new models of development based on providing hybrid urban spaces and iconic developments.

In this chapter, I will narrate the story of an individual city, Manama, in relation to local, regional and international influences. I will critically examine the major transformation that Manama has witnessed from being a small town based on pearl-diving and maritime trade to a city which is now trying to use large-scale urban projects and iconic buildings to become a global player – all with the aim of creating an international hub that will attract tourists, business visitors and investors. Ironically, Manama’s past relationship with pearl-diving appears to be endless, given that all of its newly constructed iconic projects are related to pearls – either as a morphological reference, or as an attractive commercial name that invokes history to facilitate marketing. With this type and volume of projects, Manama, like other Gulf cities in the vein of Doha, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, is undeniably one of the key centres for unprecedented levels of development in the Middle East. One ought to note, however, that it is much smaller than these other Arabic Gulf cities: Manama’s estimated population is currently around 330,000 citizens in its wider metropolitan area.

The chapter sheds light on a new emerging form of urbanisation resulting from global influences interacting within the Gulf context. Hybrid urbanism will be discussed as a major form of development which is clearly present during the last five years in globalising Gulf cities including Manama. Hybridity, as a significant result of cultural interchange and diversity, is one of the primary characteristics of global and post-global societies. I will argue that the general transformation of Bahrain’s urban identity – and that of Manama in particular – into hybrid entities, is already having a huge impact on development, imagery and social structure. The chapter will thus investigate and evaluate the impact of globalization, hybridity, and post-oil economics on the production of actual places in Manama. This topic will be studied from two perspectives: first, there will be a historical review and interpretation of the emergence of architectural and urban hybridity in Bahrain; second, there will be a closer investigation and assessment of the workings of architectural hybridity within Manama’s contemporary urbanism.

BACKGROUND TO GULF CITIES

Major cities in the Gulf region have for decades been experiencing rapid changes and transformations in their social, economic, environmental and physical structures. One of the most unique features about Gulf cities is their demographic structure. The ratio between the local and expatriate population is reaching phenomenal percentages. For instance, in the case of Bahrain, local citizens today represent only 50 per cent of the total population. An even more radical example can of course be seen in Dubai, where locals form just over 15 per cent of the population.1 What is important about these figures is that it shows the clear presence of hybrid identities within most contemporary Gulf cities. Due to economic reasons, those expatriates are often stay more or less permanently, and in the process they dwell, interact with, influence and become influenced by their surroundings. Demographic trends of the local and expatriate populations, which can be seen as ‘internal’ factors of a city, determine the rate of growth of their relative sizes and the degree of spatial differentiation or integration; whereas ‘external’ factors, mainly globalization and the shift towards hybridity, have major effects on the changing economics and lifestyles of Middle East countries. Special attention thus needs to be paid to how urban space in Manama can be shaped and dimensioned to satisfy the new expectations and needs of its diverse inhabitants, who while living in the same city environment, exhibit significant cultural and socio-economic variations.

Debates around this issue rely on our ability to understand social dynamism and what people think about their domestic environments – in other words, how they organize themselves and why. How do traditions work in society? How and why do people create new traditions? It seems evident that every society has its own continuous traditions; they may change and take on different forms, but their existence is essential for that society to survive. Citizens in Gulf cities have long tried to maintain continuity through the strong impact of their main religion, Islam. These traditions can be linked with what Rapaport calls the ‘cultural core’.2 By using this term, he differentiated the idea of essential cultural values from the more ‘peripheral’ values which are modified to suit changes in life circumstances. The real challenge for contemporary Gulf cities seems to emerge from their desire to develop in a global world, with a growing tendency towards openness and transparency. Therefore, religion might now be seen as part of a Gulf city’s identity but it is not the sole one. Beside religious factors, social structure in Bahrain has long been shaped by the power and hierarchy of tribes, and the cosmopolitanism of its demographic structure.3 Today, the right of citizenship is overriding religious beliefs and tribal allegiances in the new hybridised Gulf condition.

HYBRIDITY DISCOURSE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The contributors to the 2001 book on Hybrid Urbanism set out to revise our understanding of city building and identity formation.4 Their concept of ‘hybridity’ was borrowed from post-colonial theory to challenge both essentialist and multicultural explanations of these intertwined processes.5 According to this view, built environments and the social meanings they convey are neither the products of individual cultures nor the creations of discrete groups. Rather, they are syncretic, the result of a constant interplay of cultures and traditions. Yet, as Alsayyad rightly states, hybrid groups of people do not always create hybrid places, and hybrid places do not always accommodate hybrid groups of people.6 This argument will be used to examine the status of the newly introduced concept/process of hybrid urbanism in Manama and Bahrain in general. The hypothesis will be that due to increased openness, the desire for a more diversified economic base, and existence of multicultural groups of people, hybrid places can be created. It will also be argued that historically, cosmopolitan nature of a place or a city like Manama might facilitate the process of hybridity.

City building has often been portrayed as the self-conscious efforts of a few powerful people seeking to create distinctive and authentic urban visions. Some participants in the process in places like the Middle East might have in the past been colonialists or western authorities, while others were locals, but almost all belonged to elites who could operate within a global network of policymakers, architects and planners. This interpretation seems especially true of the modern era, although some researchers suggest that global interaction was shaping cities as early as the thirteenth century.7 Straightforward accounts of colonial dominance and indigenous resistance give way here to analyses suggesting that even in the inequitable power relationships created by Western imperialism, urban forms grew from combinations of cultures rather than the simple imposition of European ideas. In Celik’s view culture was a crucial element in power structures in the colonial condition, according to Celik.8 Architecture and urbanism have an obvious advantage over other cultural formations in shedding such direct light on social relations and power structures. Additionally, many scholars suggest that understanding urban history needs to be intertwined with the study of urban processes that embody the intricate interaction of social, economic, political, technical, cultural, and artistic forces which bring about the urban form and give dynamism to the city over time.9

5.1 Map of Bahrain showing its contextual relationship

More importantly, as argued by Bhabha, the colonial relationship is not symmetrically antagonistic, due to the ambivalent positioning of the colonizer and the colonized.10 Ambivalence is connected to the presence of ‘hybridity’ in which the other’s original identity is rewritten, but also transformed through misreadings and incongruities, resulting in something quite different. Such a process can be seen in Manama during the last decade as it has developed at significant pace into a cosmopolitan global center. Its reputation as a unique and vital trading city supports its effort to retain a regional importance and aspire to global importance. Historically, all the Bahraini cities seem peculiar: heterogeneous, hyperactive and with great deal of commercial exchange and maritime trading. This back-story has enabled Manama to go through a smooth process of transformation from a old trading city to a modern hybrid one. As Katodrytis has argued in terms of Dubai, hybrid cities demonstrate in their apparent lack of identity a complex urbanism based on an invisible infrastructure: a fluid and non-hierarchical system of activities, goods and participants. More than just a static collection of buildings, these cities can be described as a piling up of activities that change more quickly than the planning process can respond to. Katodrytis rightly states that existing buildings seem unable to sustain this dynamic, complex and fluid ‘urban condition’, one which is hybrid, synthetic and post-modern.11

A more accurate description of Bahraini urbanism can thus be generated from the fact that it is a city state in terms of urban setting. In other words, because of Bahrain’s nature as an island of very limited area, there is major difficulty in any attempt to separate the country from the city. Hence, reading Manama’s story actually gives a fair reading of the driving forces for all of Bahrain’s urbanism. In the next section, I will try to shed some light on Bahrain’s economic, cultural, social, geographical and environmental character so as to offer a deeper understanding of Manama, and given that both entities interact, overlap and intertwine continuously.

CONTEXTUAL UNDERSTANDING OF BAHRAIN

Bahrain consists of a group of 33 islands with a total land area of about 700 km2. The unique relation between Bahrain and the sea established its economic development, with its two main cities, Manama and Muharraq, originating as primitive fishermen’s settlements on the Gulf coastline. Historically, the major factors which shaped Manama were pearl fishing and trading. Bahrain was also famous for building traditional wooden boats used mainly for pearl-diving, fishing and trading. Some historical documents suggest that by the beginning of the 20th century, Oman and Qatar had purchased more than 100 fishing boats from Bahrain. The port of Manama was then so vibrant that it had over 100 trading and fishing ships entering and leaving on a daily basis.12

Looking more closely at Manama, there is a lot of evidence which shows the importance of the Gulf to the life of the city, its local community and its urban morphology. The urban structure of the road network is marked by the orientation of the main roads towards the Gulf. The old port that was once the main gate to the city, called Bab-al-Bahrain (Bahrain Gate), was a commercial hub that extended up to the main market. The city in its early stages therefore extended along the coast in a north-east/southwest direction, having a long frontage onto the coast that was then regularly interrupted by a series of lanes leading inland.13

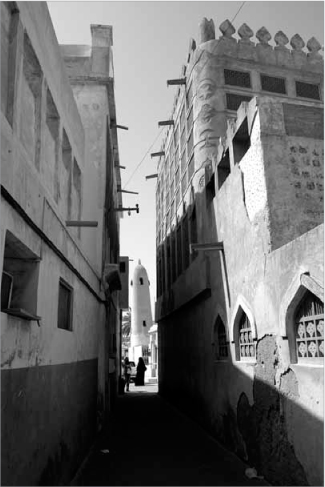

5.2 Distinctive urban and architectural features of traditional Bahraini settlements

From an environmental perspective, Manama, like most of Bahrain, is located in a hot humid climate. This climatic condition is largely responsible for its urban morphology and architectural forms. Natural ventilation is a major challenge since it is so important in buildings to try to keep out humidity. A unique street pattern can thus be noticed clearly in Manama’s spatial order. As is also observed of many traditional cities in the Middle East, the requirement for shading from the sun was achieved by having narrow winding streets.14 The tight urban pattern gives Manama’s old core its distinguishing character. In the case of wide roads, the market, communal spaces were shaded by hanging out traditional clothes. In response to the climate, the city also relied on two housing typologies. In earlier times, houses were made of very light framed structures consisting of mat huts with a sloping roof, known locally as barasti. The second typology used masonry load-bearing walls and relied on local building local expertise. Other techniques were also imported from surrounding Gulf countries to enhance the environmental performance of dwellings. For example, ventilation was improved through wind towers, locally known as badjir, which originated in Iranian traditional settlements.

Bahrain’s maritime location therefore played a crucial role in shaping its history, politics and social structure. Politically, it has long been a strategic centre between the two Islamic entities – the Arabs and the Persians, respectively the Sunni and the Shi’a Muslims – which today are regionally crystallized in the two regional powers of Saudi Arabia and Iran. Bahrain was thus a transit point between Arabia and the Persian and Indian sub-continents in many senses.15 This explains its well-established cosmopolitan demographic formed mainly of Arabs, Persians and Indians.16

While the city of Muharraq, which sits on a smaller island just to the northeast, was considered to be Bahrain’s political centre up to the late-18th century, Manama retained its purpose as the locus for foreign occupation and a focal point for regional and international trading networks. British colonial interests in Bahrain were mainly economic, with Manama acting as the base for British commercial operations in the archipelago. Only after the agreements of 1881 and 1892, when Bahrain became a de facto British protectorate, did British interference in the affairs of the islands increase dramatically. As a result, Manama became the stage for a power struggle between the Al-Khalifa rulers and the British colonists.17 This was a significant moment in the city’s history: while there had been earlier fishing settlements on the northern coast of Bahrain for centuries (references to what became Manama date back at least to the 14th century), it had been the advent of the Al-Khalifa dynasty in 1783 that transformed it into a proper urban centre. Historical sources duly note that the twin cities of Manama and Muharraq were founded soon after 1780.18 British interests thus challenged the existing power order; however, the Al-Khalifa rulers managed to survive and retain their power to the present day.

Once established as a key trading, fishing and pearl-diving centre, there were no natural barriers to Manama’s expansion due to its flat topography. Its only limits were the presence of the Gulf to the north, as well as some cemeteries surrounding the city core. Paradoxically, over the last decade, not even the Gulf was considered an obstacle to expansion given an organized and rapid process of land reclamation. The Bahrain Financial Harbour, begun in 2004, is the most important project in Manama constructed completely on reclaimed land; its second and third phases are intended to add even more land to the total area of the city. Similar projects, including man-made islands of Durrat Al Bahrain and Bahrain Bay, demonstrate the tendency to use land reclamation to accommodate iconic mega-projects.

URBAN TRANSFORMATIONS IN MANAMA

As mentioned, Manama was truly established by the end of 18th century, directly after the Al-Khalifa ruling family had achieved political stability. From 1818 to 1905, the city grew from a small village of just 8,000 people to a sizeable town of 25,000. Its role as a port city within the Gulf region made it a hub for transnational communities, most of which are now represented to different extents in the social fabric. The immigration of labourers, in search of a better life, continually shaped Manama’s population by making it be characterized by cosmopolitanism.19 Manama was also unique because it became a regional capital created by the British following the signing of the 1892 Protectorate Treaty. As a result, the city became the headquarters for British power, and was from where the whole Gulf region was managed and controlled. In terms of religion, the co-existence of the two main Islamic sects, Sunni and Shi’a, is part of the social mosaic that makes up the city.20 Both sects are represented by distinctive groups organised around large families: some are local Bahrainis, some are Persians, and some are Arab Bedouins. They once co-existed in Manama with other non-Muslim entities such as Oriental Christians, Indians of various sects, and Jews. Such a rich tapestry was further enhanced by the arrival of other ethnic communities, initially as a consequence of economic prosperity, and later due to geopolitical factors which characterized the colonial period.21

5.3 Aerial photograph showing the contrast of Manama’s old urban fabric to newer modern planning

5.4 Details of Manama’s traditional architectural vocabulary

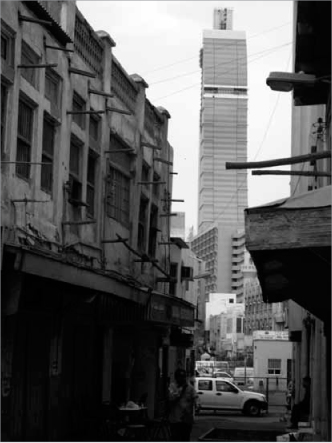

5.5 The old and the new in Manama, showing the distinctive Bahrain World Trade Centre (BWTC) and the reclaimed land for the Northern City

As in other Middle Eastern cities, Bahrain’s traditional urban form was the product of harmonious interaction between cultural norms and climatic conditions to produce effective housing clusters that used standard architectural elements and simple local construction techniques. The guiding principle was ‘Form follows Family’, according to Yarwood.22 Following the discovery of oil in Bahrain in 1930, however, it is noticeable that the traditional urban structure started slowly to change from a compact irregular organic form to a modern grid system. From 1930 until the 1960s, urban changes in cities like Manama were the result of a massive influx of foreign labour, the introduction of town-planning principles by the British colonial power, and the pursuit of a modernisation process. In 1934, the new city of Awali was built, and thereafter many modern areas adopted the ‘Form follows Function’ doctrine, sprouting out especially around traditional areas in Manama and Muharraq. In order for Manama to modernise, new functions were added to the city form: wide roads, institutional buildings, housing blocks and oil industry facilities became the new elements in this transformation. In the more traditional areas, there was also a shift of local communities to newer housing areas due to many factors: dilapidated traditional areas offered cheaper accommodation for foreign labourers, uncoordinated building activity and the absence of a comprehensive conservation strategy led to the loss of urban homogeneity in traditional areas, plus there was a widespread lack of appreciation of the value of traditional dwellings opposed to modern housing projects.23

Even though oil was first discovered in Bahrain during the 1930s, its full scale commercial production started around 1950, following the disruption of the Second World War. At this point the British colonists allowed masses of foreign workers to come into Bahrain to support the new industry. This flow of poorer labourers from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Philippines, Thailand and other parts of the Asian continent contributed substantially to new social structures. Large urban extensions outside the boundaries of Manama were established to accommodate these new communities of expatriates.24 Already by 1954, the old centre by Manama had become a small nucleus surrounded by vast modern quarters. Ever since then, a dual image between the old and the new, the past and the present, tradition and modernity has been established as a key element of Bahraini urbanism.

The … [hitherto] Oasis turned into a city of glass, iron and stone, and hordes of adventurers and entrepreneurs swarmed in. Thus patterns of behaviour, relationships and interests very different from the existing ones began to form. In the midst of all this mutation, the indigenous inhabitants were unable to adjust to the new fast rhythm and the new relationships, and in their search for a new identity they became distorted.25

Two key events in the history of Bahrain coincide perfectly and helped dramatically in its modernization process: these were Bahrain’s independence from British occupation in 1971, and then the economic boom in the Gulf region created by the ‘Oil Crisis’ of the mid-1970s.26 Many Arab researchers have argued that the subsequent benefits were manifested in the western cultural models imported to the Gulf countries, not least in terms of the built environment.27 After all, colonization had long been a crucial force in shaping the urban scene in major cities in Arab countries. In the case of Bahrain, and cities like Manama, the British had exercised extensive control from 1820 up to 1971. Following independence, dramatic changes took place in political, economic, social and cultural spheres.

Urban changes in Manama had started to accelerate in the 1960s, even before independence, due to population growth and the pressure for modernisation. The Isa Town was built in 1963, followed later by Hamad Town in 1982. Both areas were built based on the western planning philosophy of the grid-iron system and zoned land use, and were implemented in favourably prosperous economic conditions. Indeed, the oil boom of the 1970s was to have a dramatic social and economical impact on Manama’s local community. The city witnessed a rapid outwards migration of local inhabitants to newer settlements as an indication of economic prosperity and the move towards modernization.28 Living in the old core of Manama became perceived as an indication of poverty and backwardness. Subsequently, the new edges of Manama’s old core gradually turned into an administrative and business centre. More dramatically, low-income expatriate groups transformed the older districts by turning traditional houses into ever-denser residential quarters to accommodate the rapid increase in labourers working in different development projects around the city.

During the mid-1980s, however, there arose a strong regionalist movement calling for a rethinking of the western models of urban planning and architecture implanted into Bahrain and other Gulf countries. According to Mortada, there were two major reasons for this ‘awakening’.29 The first was the realization of the socio-cultural inappropriateness of western models. The second factor was more related to the environmental sustainability movement that started in western countries around the mid-1970s. We might also add to this the emergence of Arabic regionalism that demanded design and planning ideas drawn from traditional local cultures. It was trend celebrated by the Aga Khan Trust’s establishment in 1977 of the most prestigious and generous architectural award in the world to encourage local, regional and international designers to create architecture that improves the physical environment of Muslim people, and which recognises more distinctive Middle Eastern models of architecture and planning.

5.6 Bab Al-Bahrain Mosque as a representation of Islamic regionalism in a modernizing city

The invitation of influential regional architects like Mohamed Makiyah and Abdel Wahid Al-Wakil, both recipients of the Aga Khan Award, to design in Bahrain during this period was a clear manifestation of this regionalist movement. Both successfully managed to design two of the most important landmarks of Bahrain at that time: the main gateway into Isa Town and the Bab Al-Bahrain mosque respectively. Their influence was echoed in a variety of institutional buildings, hotels and new dwellings for local people around the outskirts of Manama. In these designs, the interpretations of Islamic regional architecture reached far greater levels of understanding and depth.

Later still, the last decade of the 20th century is so crucial to understanding Manama’s urbanization, for that was the period when globalising influences started to reach the Middle East.30 It is of course necessary to question if there is evidence of a new spatial order resulting from globalization, and whether this influences a Middle Eastern city like Manama. The impact of globalization on cities in developed and developing countries has been a focus for numerous commentators.31 They all agreed on the main causes such as capital flow, labour markets, information flow, management and spatial organization. One can conclude from this a simple definition that a city is globalised if it has the ability to capture economic flows through linkage-based strategies and connectivities within the overall morphology of the global urban system. Since the 1990s, Bahrain’s urban development indeed entered a new phase of globalisation with the encouragement of external investment, trade and tourism, and the resulting growth in real-estate projects. Urban form now started to be influenced by a new slogan, ‘Form follows Finance’.32 From the point of view of urban space, Manama’s historical core witnessed a tangible spread of new hotels along its waterfront edge. In addition, institutional and financial buildings continue to be constructed around the urban peripheries and along main roads into the city.

5.7 Aerial photo showing Bab-Al-Bahrain, Bahrain Financial Harbour and the renovated Manama Souk

MANAMA’S PREPARATIONS FOR A POST-OIL WORLD

As mentioned earlier, in Bahrain’s case the diversification into the financial and tourist sectors was more urgent than for its Gulf neighbours: it had been the first Gulf country to discover oil resources but also the first to encounter their depletion. Manama entered the post-oil paradigm by emphasizing its new role as a global financial hub for the region, especially in terms of banking. Manama is indeed one of the oldest banking centres in the Gulf and has over 350 financial institutions today.33 Due to a favourable new free-trade agreement with the USA, Bahrain became even more open to foreign commerce. All these factors have rejuvenated its economic market, and there countless commercial, financial and other real-estate projects in the pipeline in Manama. More importantly, a fundamental focus on tourism as an economic pillar based on Bahrain’s unique and diverse history has been intensely developed over the last five years or so.

Tourism is a major international industry, with many countries all over the world now relying on the income it produces. The demands of tourism can however contribute to the destruction of the natural and cultural environment upon which it depends. It is essential, as Pineda and Brebbia argue, to find ways to protect these environments for future generations.34 Therefore there is a need to explore issues linked to the environmental, social and economic sustainability of tourism alongside governance mechanisms needed to support sustainable tourism. I would suggest that a struggle to achieve sustainable and cultural tourism is absolutely crucial in a locality rooted in authentic traditions. A key component of any sustainable tourism strategy lies in its ability to incorporate local communities, and also important is the role of other communities surrounding the touristic sites. In any cosmopolitan city, such as Manama, the presence of different immigrant ethnic groups is inevitable. Hence, cultural diversity and all its manifestations need to be transformed into vehicles for socio-economic development to the advantage of both immigrants and the city at large, as Rath argues.35 In the context of Middle Eastern cities, according to Daher, the discourse of tourism should be linked to issues like cultural heritage and identity construction, national and global economics, and the development of local communities.36 This analysis implies that issues like national identity, authenticity, representation of cultures and regions, and community and tourism development are of vital importance to understanding what role tourism can play in the economic development of Middle Eastern cities like Manama.

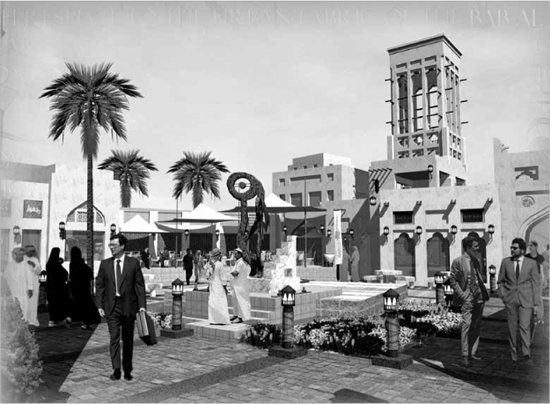

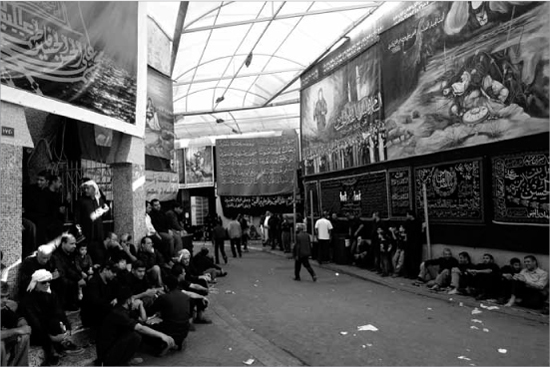

5.8 Manama’s old core being ‘invaded’ by expatriate communities imposing their cultural references and hybrid lifestyles

Here it is worth sketching the forces which are reshaping today’s tourism industry in the light of issues related to identity, heritage and religious/ethnic festivities. Touristic practices in relation to forms of traditional and contemporary religious festivity are crucial, since the relation between the place and the event adds another dimension to the richness of the traveller’s experience. Rath in particular is interested in the interrelationship between tourism, migration, ethnic diversity and place.37 In Manama, a fascinating example of touristic development is found on the opposite side of Bab Al-Bahrain, in the renovated Manama Souk (see Plate 7). This souk is located within the old city core and is considered as Bahrain’s oldest. With its traditional architecture of narrow roads and little shops, the project cost around US$ 90 million when finished in late-2009. The souk has since become a must-see tourist experience where one can buy all kinds of spices, fabrics, handicrafts, souvenirs, dried fruits, nuts, and other traditional goods. The crowd as well as the traders in Manama Souk consists of Bahrainis as well as expatriates from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and neighbouring Gulf countries. As the architects, Gulf House Engineering, proclaimed:

5.9 Renovation of Manama Souk opposite to Bab Al-Bahrain Mosque and the waterfront

5.10 Manama’s emerging urbanity of vertical towers, shopping malls and financial centres

We seek continuity, sustainability and balance through our culture and architectural heritage, in such a symbolic, traditional, environmental and homogenous district. The design is comprehensive as micro-scale architectural language complements macro-urban design. We preserve identity and respect the alphabet of the architectural vocabulary of the region.38

This revealing quote from the project report reflects the social, cultural, environmental and economic agenda of the developers, as substantiated by a series of project objectives. Two of these objectives deserve to be spelled out. The first is of attracting tourists and other expatriates to visit the area by providing activities, shops, and urban infill projects to meet their needs, and provide an experience worth travelling for. The second objective is the importance of providing a theme for the Manama Souk in terms of rehabilitating buildings and creating public spaces and other facilities. According to the project master-plan, the area is divided into zones such as the ‘cloth zone’, ‘gold souk’, ‘spice souk’, and even an area called ‘Little India’! None of the goals mentioned in the report, however, refer to the local community, older shopkeepers, or the presence of diverse ethnic groups. But it is this unique tapestry which gives the urban area its character and helps to construct its hybrid identity.39 As the project manager stated:

Manama Souk renovation will positively contribute in boosting commercial activities and increase number of visitors and tourists coming to the area dramatically … The objective of the project is to preserve the unique heritage and traditional character of the souk and activate its touristic and cultural roles which were endangered due to unplanned increase in surrounding high-rise buildings.40

Paradoxically, the renovated vision for the souk stresses the ideals of continuity, sustainability and balance. Preserving the area’s identity was limited to using architectural vocabulary only from the Gulf region, without considering how this will fit in with, say, ‘Little India’. Here in Manama Souk, a clear example of Eco’s ‘authentic fake’ has been constructed.41 Real sources of authenticity have been neglected in favour of the fakeness of a questionable imported architectural vocabulary. Ahmad Bucheery, the local Bahraini architect who works for Gulf House Engineering, and who was the figure commissioned to design the renovated souk, earned his reputation as an architectural traditionalist after designing a famous hotel along the old link connecting Muharraq to Manama. In that scheme, Bucheery used all architectural vocabulary inherited in traditional Gulf architecture including wind-catchers to impress the hotel’s guests and associated visitors. In an essay on ‘Contemporary Architecture in Bahrain’, he divides the development of Bahraini architecture into five stages: the traditional; the transitional period; the modern; the post-modern; and finally, identity revivalism.42 Surprisingly, Bucheery concluded his essay with a position that rejects copying from the past, and instead preaches innovation and creativity:

We, in Gulf House Engineering, have attempted through the various projects to go beyond the simple copying of the past through innovation, interpretation, and reflection. We are trying to balance between tradition and modern, simultaneously “localizing” international ideas, materials and aspirations to suit local needs. We hope that the new millennium will bring architectural achievements that truly reflect the identity of the Bahraini people and their local architecture.43

Another missing dimension in the redevelopment of the Bab Al-Bahrain/Manama Souk area, and which contributes to its fakeness, is the absence of festivities, especially religious ones. Being in the centre of old Manama, it sits on several festival routes, but the multi-faceted relationship between tourism and festivals was simply not incorporated into the new development of the Bab Al-Bahrain/Manama Souk. It is a real loss, since the religious events and ceremonial processions performed by Shi’a groups for the anniversary of Imam Hussain (the martyred grandson of the Prophet Mohammed) sees the use of urban space and street furniture change dramatically. The ceremony extends for ten days and reaches its climax on the night of the tenth day, which is called the Day of Ashura (see Plate 8). Tens of thousands of people poured towards the streets and alleys of Manama either to participate or simply to see the events. Inspired by the ‘Arab Spring’ revolts in Tunisia and Egypt, crowds of up to 150,000 mainly Shi’a Bahrainins demonstrated in the heart of Manama during February and March 2011. Their replica of Cairo’s Tahrir Square was Pearl Square. The protest wave was suppressed by heavy army intervention supported by military forces brought in from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab of Emirates, causing many fatalities. To eliminate any further mass protest or any occupation of main public spaces, the Bahraini authorities stormed Pearl Square. Protesters were evacuated and then the whole square including its central landmark sculpture – symbolizing Gulf Cooperation Council unity – was razed to the ground. These events however only brought further to the surface the importance of a need for just coexistence in Manama and Bahrain.

Another critical dimension affecting not only Manama but literally every single city in the Middle East is the impact of Dubai, or more specifically what is often described as ‘Dubaification’ or ‘Dubaization’.44 As is well known, the contemporary urban scene in Dubai is characterized by an infusion of new privately-owned building types: shopping malls, gated housing communities, theme parks, and headquarters of multinational corporations. Dubai’s leaders, also realising the realities of oil depletion, have constructed an unprecedented model of development based on economic diversification and a reliance on services industries, not least tourism.

5.11 Spectators waiting for the main procession on the Day of Ashura

5.12 Religious festivities change Manama’s urbanism radically especially in the evening of the Day of Ashura

5.13 Dubai’s coastline showing the built and proposed iconic development islands of ‘The Palm 1, 2 & 3’ and ‘The World’

All along the beaches stretching away from Dubai’s famed creek, armies of overseas construction workers are once again racing to complete giant housing complexes which will permanently change the lie of the land. To visualize the scale of development, the case of Al Nakheel Properties offers an interesting example. This one developer has designed a series of residential environments whose opulence rivals anything in southern California or Florida’s ‘Gold Coast’.45 In one development known as ‘The Palm’, three man-made palm-tree-shaped islands were created for expensive condominiums and yacht basins. It is promoted as the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’, in part because, like the Great Wall of China, it can (just about) be seen from outer space. Al Nakheel was so pleased with the result that it went on to build ‘The World’, a collection of 300 man-made islands shaped like a map of the continents.

Most of the Arab cities aspiring to world status have been competing to imitate Dubai in the unprecedented effort to build the tallest and the largest-ever architectural and urban statements. A growing number of projects around the Gulf show the severity of this competition: examples include Abu Dhabi’s Sorouh project, Bahrain’s Financial Harbour, Qatar’s Pearl Development, Oman’s Blue City and Riyadh’s Desert Islands. More importantly, it represents the dramatic influence of Dubai’s icons on the developmental strategies of these cities, hence the term ‘Dubaization’. Elsheshtawy argues that the development of Dubai as a global centre remains unique, in that it now serves as a ‘potential model for other cities in the region’.46 However, Dubai as a model of urban development for contemporary Arab cities is entirely lacking, since it is based primarily on images and icons rather than sustainable concepts and strategies. For today’s Arab cities which imitate Dubai the result from this process is the failure to consider sustainability in development planning, as well as limited interpretation of what globalization might mean and the resulting degradation of a sense of locality.

5.14 The ‘Palm 1’ project is already a major manifestation of Dubai’s new urban brand

5.15 Bahrain Financial Harbour (BFH) emerging close to Manama’s old traditional core

Dubai’s new urban brand not only creates a developmental model to be followed by Gulf and Arab cities, but it also promotes the role of Dubai-based development companies to extend these vast projects outside their home city. Dubai International Properties unveiled plans to build the Salam Beach Resort and Spa in Bahrain, located on the south-west coast of the main island, and completed in mid-2009. The announcement of this project in Bahrain came soon after their vast projects in Qatar, Oman, Morocco and Turkey, making Dubai International Properties one of the fastest growing real-estate developers in the region.

It is also a process which is being taken up vigorously in Manama itself. Evan just a decade ago, the skyline of Manama was dominated by the 29-storey tower of the National Bank of Bahrain. Since then, however, a newly introduced sense of verticality has gradually changed the image of the city (as well as the rest of Bahrain). It marks the beginning of a new era of iconic development. Manama, like many other Arab cities, has therefore subscribed to the ‘Dubaization’ process. This was clearly prompted by the need to respond to Dubai, which due to its unprecedented growth and unmatched desire to become a unique, global-scale model had also aggressively captured the hitherto role of Bahrain as the mixing point and the financial, commercial, recreational hub of the Gulf region. Hence in responding to Dubai’s challenge, Bahrain has been forced to develop a new rhythm of urban development, with iconic towers and an increasing number of shopping malls becoming today the visible signs and symbols of globalisation.47

Bahrain is now basking in the glory of its financial might and throwing it doors open to international visitors with a flurry of cutting-edge business landmarks and boutique hotels. On one hand are the multi-functional skyscrapers which now characterize the waterfront: projects like Bahrain’s Financial Harbour, Bahrain World Trade Center and Bahrain Bay are good examples of a new vertical dimension added to Manama’s image. Secondly, there is a spread of man-made fantasy islands to promote exclusive lifestyles (see Plate 9). Mega-developments like Durrat Al Bahrain, Amwaj Islands and Lulu Islands are representations of this category. Durrat Al Bahrain (Bahrain’s Pearl), a 20 km2 area of desert and sea, will be one-and-a half-times larger than downtown Manama. Originally scheduled for completion in late-2010, at full capacity it is intended accommodate more than 30,000 permanent residents in addition to some 4,000 visitors a day on its fifteen crescent- or fish-shaped islands. Obviously, the global financial crisis and the recent 2011 revolt in Bahrain have delayed the completion of the project, and indeed affected the pace of development in Manama as a whole.

5.16 The fast-changing Manama waterfront and with the iconic BWTC and BFH towers dominating its skyline

5.17 Manama’s reclaimed north shoreline, adding new urban centres such the Northern City and Al Seef commercial area

5.18 Durrat Al Bahrain, a new iconic resort development on the southeastern coast of the main island

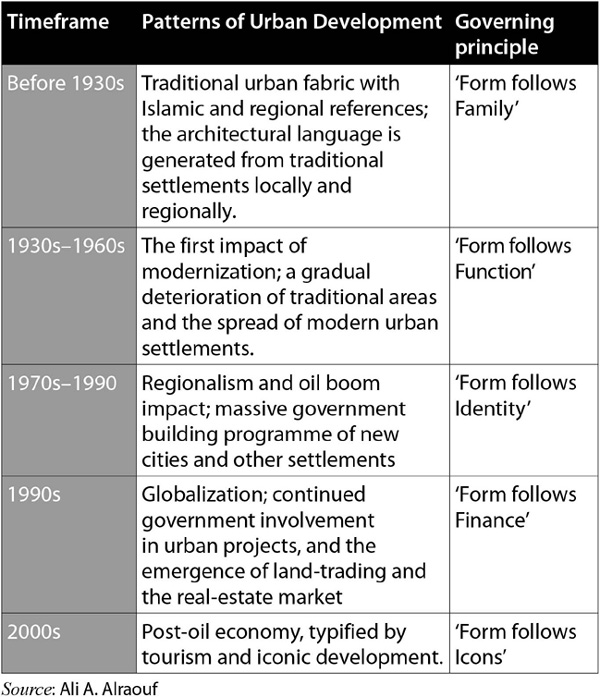

Table 5.1 Urban development in Manama and Bahrain – main paradigms and transformations48

5.19 Continuous land reclamation is changing Manama’s urban morphology at an unprecedented pace, here showing the northern coastline from the BFH Tower to the Al Seef district in the distance

HYBRID URBANISM IN CONTEMPORARY BAHRAIN

The issues discussed in this chapter lead inevitably to questions about developments following Bahrain’s independence as well as its contemporary situation as a globalising country. Bahrain is witnessing dramatic changes in land use and spatial organization generated by the accumulation of successive economic shifts. It passed from pearl-diving, fishing and maritime trade to an oil-based economy in the early-1930s, and more recently has entered the globalised economy through the promotion of the financial and tourist sectors. Likewise, a new type of urbanism emerged. Yet this reality has nothing to do with traditional or modernist dogmas: it is a spontaneous condition, driven by an instinct for survival, utility, money and fantasy. In an act of self-stylization, Bahrain is a raw experiment in the context of ‘hybridization’, where any proposed structure is ultimately measured by its ability to thrive in new and unpredictable conditions.

It seems that Bahrain is smoothly entering the new paradigm of a post-oil economy, which makes hybrid urbanism an unavoidable process. The challenge for Manama, as indeed for other Gulf cities, is not how to stop hybridity but how to integrate it into a more holistic process of sustainability. Sustainability emphasizes the integrated nature of human activities and therefore the importance of comprehensive planning which is coordinated between groups. Planning for sustainability implies creating liveable, equitable and ecologically-minded communities. Wheeler has stressed that the concept of sustainability has to be extended all the way from the planning level to the individual building site.49

While the architecture for the rehabilitation of the Manama Souk is to a great extent a fake representation of the past, the event of the Day of Ashura and its sacred power to collect thousands of people together is the most authentic dimension of this part of the old city. All new developments should focus on the event as the generator of the spatial and social spirit of the local context. As Frenchman argues convincingly, the making of good event-places represents far more than successful urban design. It becomes a powerful means of city building because it creates both social and physical capital, and as such contributes to the local economy.50

We must not forget that all of the Arab Gulf countries have been fortunate. They are oil-and-gas rich states, and although reserves are dwindling, prices are going down, and other energy alternatives are emerging, they are still able to use oil and gas revenues to develop projects to diversify their economies.51 The grand plan for most of the Gulf economies is that in future they will become knowledge-based, which means that the services sector will be ever more important. Manama is moving with giant steps in this direction by using its financial resources and historical reputation as the Gulf’s original financial centre. It needs however to add an ecological dimension to its thinking, and in that regard, here a useful definition given at the Sustainable City Conference in Rio de Janeiro in 2000:

The concept of sustainability as applied to a city is the ability of the urban area and its region to continue to function at levels of quality of life desired by the community, without restricting the options available to the present and future generations and without causing adverse impacts inside and outside the urban boundary.52

Another important conclusion lies in acknowledging the contemporary challenge for globalised cities to maintain their ability to be different, avoiding physical homogenization. The argument is more severe in the case of Gulf cities given the magnitude of Dubai’s impact (even if the current global financial crisis has shown to all just how much Dubai’s economy is suffering from speculation and inflated real estate profits). All cities have historically been key contributors to personal and local identity. In the era of globalization, urban difference can also be a guarantor of social and political differences. As Sorkin argues, the crucial question is what are the sources of fresh and authentic difference within the spreading ocean of global uniformity.53 He suggests three sources; the environmental genius loci, the model of the city as an autonomous environmental, political and economic entity, and the role of artistic invention in creating genuine and meaningful differences within urban patterns.

In the light of this chapter, we clearly need to keep up a continuous interpretation of relationship between Bahrain’s post-oil economy and the development process in cities like Manama. This will involve examining the effects of the phenomenon of globalization on urban spaces in Bahrain’s cities, whether in analyzing iconic developments for their social, cultural and environmental consequences, or the spatial impact of hybrid urbanism and the globalisation paradigm on architectural and urban spaces. From this we then need to suggest concepts, strategies and processes to incorporate a more sustainable approach to community development in the kingdom of Bahrain. It is clear that our future cities need to be sustainable; this is no longer a choice, it is an urgent demand for the coming generations. Cities in the Gulf region, in approaching the post-oil economy era with confidence, can show that they can be hybrid, globalized and sustainable.

NOTES

1 The recent global financial crisis has highlighted the negative consequences of such a demographic structure. See: Lucia Dore, ‘Innovation and entrepreneurship critical to Middle East economies’, 17 March 2006, Khaleej Times website, http://www.khaleejtimes.com/DisplayArticle.asp?xfile=data/business/2006/March/business_March333.xml§ion=business&col (accessed on 24 September 2010).

2 Amos Rapaport, ‘Culture and Built Form – A Reconsideration’, in David G. Saile (ed.), Architecture in Cultural Change: Essays in Built Form and Culture Research (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas, 1986), pp. 157–175.

3 Nelida Fuccaro, Urban History of Bahrain (Bahrain: Excess University, 1999); Nelida Fuccaro, ‘Islam and Urban Space: Ma’tams in Bahrain before Oil’, Newsletter of the Institute for the Study of Islam in the Modern World (July 1999), p. 12; Nelida Fuccaro, ‘Understanding the Urban History of Bahrain’, Journal for Critical Studies of the Middle East, vol. 17, no. 2 (2000): 49–81.

4 Nezar Alsayyad (ed.), Hybrid Urbanism: On Identity Discourse and the Built Environment (New York/London: Praeger, 2001).

5 Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003).

6 Nezar Alsayyad, ‘Hybrid Culture/Hybrid Urbanism: Pandora’s Box of the “Third Place”’, in Alsayyad, Hybrid Urbanism.

7 Thomas R. Gensheimer, ‘Cross-Cultural Currents: Swahili Urbanism in the Late Middle Ages’, in ibid.

8 Zeynep Celik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997).

9 Janet Abu-Lughod, ‘On the Remaking of History: How to Reinvent the Past’, in Barbara Kruger & Phil Mariani (eds), Remaking History (Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1989), pp. 111–129; Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1974/91).

10 Homi K. Bhabha, ‘The Other Question: Difference, Discrimination and the Discourse of Colonialism’, in Russell Ferguson et al. (eds), Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Culture (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1990), pp. 71–87.

11 George Katodrytis, various design projects and written texts on ‘Hybrid Urbanism and Constructed Identity’, 2004.

12 John Gordon Lorimer, Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf – Oman and Central Arabia (2 vols, Cambridge: Cambridge Archive Editions, 1908–15/86).

13 Fuad Khuri, Tribe and State in Bahrain: The Transformation of Social and Political Authority in an Arab State (Chicago, IL/London: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

14 Besim S. Hakim, Arabic-Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles (London/New York: Kegan Paul International, 1986).

15 Mahdi Abdalla Al-Tajir, Bahrain 1920–1945 (London/New York/Sydney: Croom Helm, 1987); James Belgrave, A Brief Survey of the History of the Bahrain Islands (London: Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, 1952).

16 John R. Yarwood, ‘Al-Muharraq: Architecture, Urbanism, and Society in an Historic Arabian Town’ (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, 1988).

17 Mohammed G. Rumaihi, Bahrain: Social and Political Change since the First World War (London: Bowker, in association with Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies of the University of Durham, 1976).

18 Tariq Wali, Al-Muharraq 1783–1971 (Bahrain: Gulf Panorama, 1990). See also Fuccaro, ‘Understanding the Urban History of Bahrain’, pp. 57–59, 65–72.

19 Nelida Fuccaro, ‘Mapping the Transnational Community: Persians and the Space of the City in Bahrain 1869–1937’, in Madawi Al-Rasheed (ed.), Transnational Connections in the Arab Gulf (London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 39–57.

20 Fuad I. Khuri, Tribe and State in Bahrain (Chicago, IL/London: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

21 Fuccaro, ‘Mapping the Transnational Community’.

22 Yarwood, ‘Al-Muharraq’.

23 Souheil El-Masri & Fa’eq Mandeel, ‘Urban Planning Institutions in Bahrain’, 8th Sharjah Urban Planning Symposium Proceedings (Sharjah: SUPS, 2005), pp. 214–227.

24 Fa’eq Mandeel, ‘Planning Regulations for the Traditional Arab-Islamic built Environment in Bahrain’ (Unpublished MPhil Thesis, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, 1992).

25 Quote from Abdul Rahman Munif in Rasheed El Enany, ‘Cities of Salt: A Literary View of the Theme of Oil and Change in the Gulf’, in Ian Richard Netton (ed.), Arabia and the Gulf: From Traditional Society to Modern States (London: Croom Helm, 1986), p. 216.

26 Shirley R. Taylor, ‘Some Aspects of Social Change and Modernization’, in Jeffery B. Nugent & Theodore H. Thomas (eds), Bahrain and the Gulf (London: Croom Helm, 1985).

27 Jamel Akbar, Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City (Singapore: Concept Media, 1988); Saleh Al-Hathloul, ‘Tradition, Continuity and Change in the Physical Environment: The Arab-Muslim City’ (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 1981).

28 Curtis E. Larsen, Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

29 Hisham Mortada, Traditional Islamic Principles of Built Environment (London: Routledge Curzon, 2003).

30 Stefano Bianca, Urban Form in the Arab Worlds: Past and Present (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000); Gerald H. Blake & Richard I. Lawless, The Changing Middle Eastern City (London: Croom Helm, 1980).

31 Saskia Sassen, Global Networks, Linked Cities (London/New York: Routledge, 2002); Manuel Castells, The Rise of The Network Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1996).

32 Carol Willis, Form Follows Finance: Skyscrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1995).

33 Methil Renuka, ‘Money Talks’, Business Traveler: Middle East (July/August 2007): 18–22.

34 Francisco D. Pineda & Carlos A. Brebbia (eds), Sustainable Tourism II (Southampton: WIT Press, 2006).

35 Jan Rath, Tourism, Ethnic Diversity and the City (London: Routledge, 2006).

36 Rami Daher, Tourism in the Middle East: Continuity, Change, and Transformation (Bristol: Channel View Publication, 2007).

37 Rath, Tourism, Ethnic Diversity and the City.

38 Quoted in the ‘Bab Al-Bahrain Area Development Design Report’ by Gulf House Engineering for the Ministry of Municipalities and Agriculture Affairs, Bahrain (2006).

39 This debate around architecture, urbanism and identity is the main concern of numerous researchers. See, for instance: Cliff Hague & Paul Jenkins (eds), Place Identity, Participation and Planning (London: Routledge, 2004); Anthony D. King, Spaces of Global Culture: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity (London/New York: Routledge, 2004); Liane Lefaivre & Alexander Tzonis, Architecture and Identity in a Globalized World, Architecture in Focus Series (London: Prestel, 2003); William Neil, Urban Planning and Cultural Identity (London: Routledge, 2003).

40 Mohammed Al-Makdadi, Project Manager for the Manama Souk, as quoted in Gulf News, 26 February 2008, p. 13.

41 Umberto Eco, Faith in Fakes: Travels in Hyperreality (New York: Vintage, 1986).

42 Ahmed Bucheery, ‘Contemporary Architecture in Bahrain’, in Jamal Abed (ed.), Architecture Re-introduced: New Projects in Societies in Change (Geneva: Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 2004), pp. 62–69.

43 Ibid., p. 69.

44 Ali A. Alraouf, ‘Dubaization vs. Glocalization: Territorial Outlook of Arab/Gulf Cities Transformed’, paper presented to 9th Sharjah Urban Planning Symposium, Sharjah, UAE, 2–4 April 2006.

45 For a more detailed review of the real-estate boom in Dubai, see ‘Arab Property: Boom Time’ (special issue), The Middle East Journal, no. 395 (2005): 34–39.

46 Yasser Elsheshtawy (ed.), Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 17.

47 Souheil El-Masri, ‘Towards Intelligent Urban Sustainability: Reviews of Initiatives & Future Prospects in Bahrain’, paper presented to 6th Sharjah Urban Planning Symposium, 6–8 April 2003, Sharjah.

48 The table was developed as a result of findings in Yarwood, ‘Al-Muharraq’ and in El Masri & Mandeel, ‘Urban Planning Institutions in Bahrain’.

49 Stephen M. Wheeler, Planning for Sustainability (London: Routledge, 2004).

50 Dennis Frenchman, ‘Event-Places in North America: City Meaning and Making’, Places, vol. 16, no. 3 (2004): 36–49. In this essay, Frenchman stresses that the popularity of event-places in the North American context has to do with a search for meaning in American public life and a yearning for community.

51 See the GCC hospitality report in Gulf Business (May 2007): 86–89. Here Guy Wilkinson sheds some light on the fact that the hotel projects in the pipeline and those under execution are countless, and he questions whether the market is open to that need. He states that the average rate of increase of hotel chains and rooms has been close to 60 per cent each year for the last five years.

52 Guy Battle & Christopher McCarthy, Sustainable Ecosystems and the Built Environment (London: Wiley-Academy, 2001), pp. 88, 91, 96.

53 Michael Sorkin, ‘Difference in the Global City’, abstract in special conference issue of Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, vol. 16, no. 1 (Fall 2004).