MEDIA COVERAGE AND USERS’ REACTIONS

Al Azhar Park in Cairo re-examined

Introduction

This chapter examines the hypothesis that projects celebrated in the public or specialized media are not necessarily meeting users’ expectations or satisfying their needs. This premise is derived from the contemporary design discourse that emphasizes that influential publications foster the image of architecture as art and only art (Nasar 1986; Sanoff 1991; Salama 1995). They present the formal aspects of the work of star architects where the creation of the built environment is seen within geometric abstract and artistic terms. It is possible to assert that in the media typically very little attention is given to users’ feedback or behaviour, needs or expectations. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged that a considerable portion of the general and architectural media still adopt the view of architecture as art; thereby the media content is expected to be supportive of this view. Stemming from this argument, the purpose of this chapter is to examine whether the intensive media coverage of Al Azhar Park, a massive project that is portrayed as a new green lung for Cairo, as a sustainable urban development project indicates its success from the users’ perspective.

A multilayered methodology was devised in a manner that involves the implementation of two investigation mechanisms. The first is a preliminary content analysis of a total of 64 online and printed publications that covered the project in reporting, descriptive, as well as analytical terms. The objective of this procedure is to discern the way in which the project was portrayed in the media and what aspects were most praised. The second mechanism is a survey that involves users’ reactions to park design, nature of activities, and management issues. Responses from 184 users were analysed while relating aspects celebrated in the media to users’ feedback. By developing knowledge on how the users and visitors of Al Azhar Park perceive the project and how the spatial qualities meet their needs, an in-depth insight into the understanding of the merits of the project is developed. In addition, assessing different aspects of the park may reveal specific shortcomings, which could eventually lead to recommending ways of improvement.

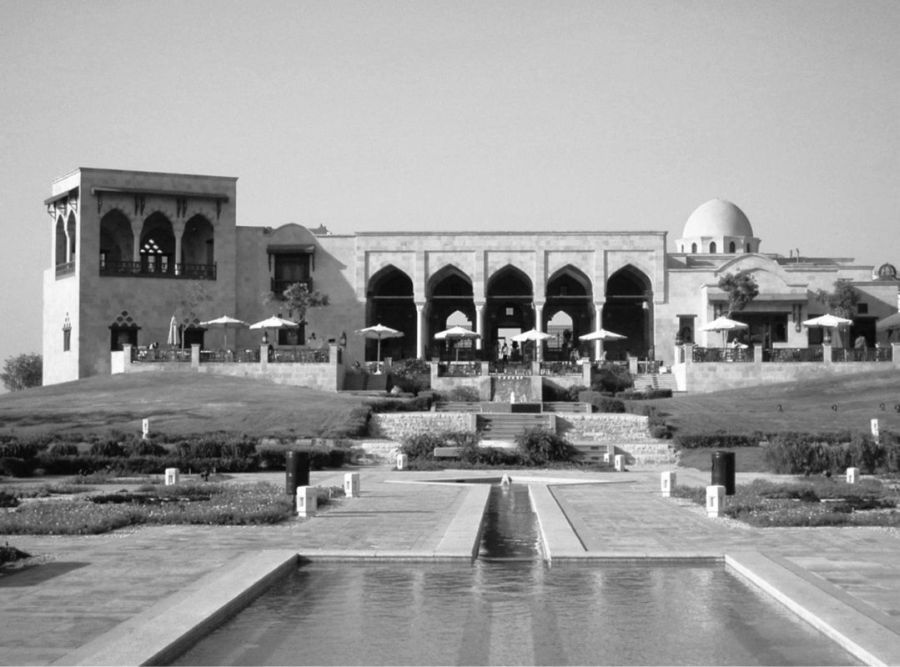

FIGURE 8.1 View of Al Azhar Park to the north

Source: photo by Gary Otte, Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Geneva.

Spatial quality and key design features of the park

Spatial quality involves physical, symbolic, behavioural, and experiential aspects (Rapoport 1970). Thus, selected physical features of the project at the micro, meso, and macro levels are introduced to underscore some of these aspects. The park was conceived to include: main spine (palm colonnade); formal gardens; hilltop lookout kiosk; hilltop restaurants; children’s structured play area; children’s amphitheatre and stage; lookout plaza; water cascade and stream; and lake (Figure 8.1). These elements are missing from most public spaces in Cairo and consequently the behavioural and experiential aspects underlying spatial quality (Salama 2008). Relating its visitors to Cairene heritage, the park was strategically planned, by Sites International, to provide an exceptional panorama of prominent monuments. From the hilltop restaurant in the northern section of the park towards Cairo Citadel runs a linear main spine that ends at the southern section of the development at a man-made lake and a lakeside café (Figure 8.2), which provides scenic views to mosques and minarets. Branching from the main spine are many smooth and flat areas of lawn, fountains, and flowering trees and plants (AKTC 2001).

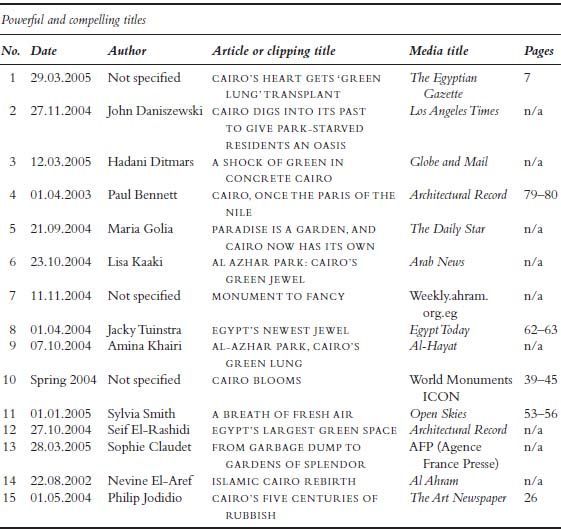

Dramatically situated adjacent to the lake is the lakeside café, designed by the French architect Serge Santelli, overlooking eye-catching views (Figure 8.3). It offers a remarkable balance between contemporary style and principles of Islamic gardens. Such principles include the prevalence of symmetrical forms, the use of water features, the commonness of shaded areas, and wooden screens (Mashrabiya). These features are manifestations that the park enjoys unique symbolic qualities and that it was conceptualized as a series of areas and enclosed zones along the central passage system. The hilltop restaurant is located in the north, designed by local architects Ramy Al Dahhan and Soheir Farid to simulate conventional Mamluk architectural motifs and themes. It encompasses large indoor and outdoor open spaces on different ground levels (Figure 8.4) that include an external terrace, internal banquet hall, a gallery space, and a manzara (roofed overlook porch). Further north is a small amphitheatre with a stage which serves the park’s musical programme and nearby services were created on the western side facing a major round twelfth-century tower. Adding to the experiential quality of the park, several other features include car-free zones where visitors may be transported within the park by a small rubber-tyre train, while its operations team uses electric vehicles (i.e. golf carts). In addition, tree lighting and lighting of the water elements are used with the intention to provide sufficient lighting, thus allowing the public to visit until midnight. Usable green spaces were maximized to take up to 10,000 persons on any given day (AKTC 2001).

FIGURE 8.2 View to the north of the park through the main spine

Source: author.

FIGURE 8.3 View to lakeside café through the lake

Source: author.

FIGURE 8.4 Front view of hilltop restaurant showing outdoor terraces and the Mamluk architectural motifs adapted to create a contemporary image in harmony with the context

Source: author.

While the preceding analysis concerns itself with the micro level, at the meso level the redevelopment of Darb Al Ahmar district and the restoration of the Ayyubid wall and other landmark buildings are important manifestations. The clearance of the slum upon which the park was built was part of a socio-economic drive, intended to improve the overall condition of the surrounding district. Buildings of historical value and homes were renovated. After surveying the area’s residents, a list of priorities as viewed by the community was developed and included training programmes, sanitation, housing rehabilitation and renovation, micro-finance, employment, and health care. At the macro level, Al Azhar Park’s profile is much appreciated by the larger city.

Media coverage of Al Azhar Park scrutinized

In examining the media coverage of Al Azhar Park project a number of procedures were conducted. First, all the available articles were collected, together with clippings or announcements from a wide variety of sources including printed and online published texts of newspapers, magazines for public consumption, and specialized trade architectural and design magazines for professionals. A total of 64 articles, written in English and published during the period between 2002 and 2005, were identified for investigation. Second, a ‘content analysis’ procedure was conducted to examine the selected articles involving the following steps:

• Reading through all the articles to get a preliminary sense of the range of concepts or issues involved.

• Repeating the previous step while citing all the major issues to identify and establish categories of concepts and terms and their underlying meanings.

• Conducting a search in order to determine frequency of concepts or terms where the written text would match the established categories. It is noted that the underlying concepts or terms that represent essentially the same issues are cited under the same heading or category.

• Transforming the categories of ideas or concepts into numerical values.

The concepts or terms identified to perform the investigation included:

• Redevelopment, which includes meanings that pertain to revitalization, rehabilitation, and restoration.

• Slum Clearance, which encompasses meanings related to soil, garbage, and poverty.

• Cairo’s Past, which involves terms such as Islamic Heritage, or reference to specific historical eras.

• Recreational Space, which refers to words or phrases that include fresh air, pollution, greenery, green space, and oasis.

• Socio-Economic Development, which refers to community related issues including community involvement, employment, and loans.

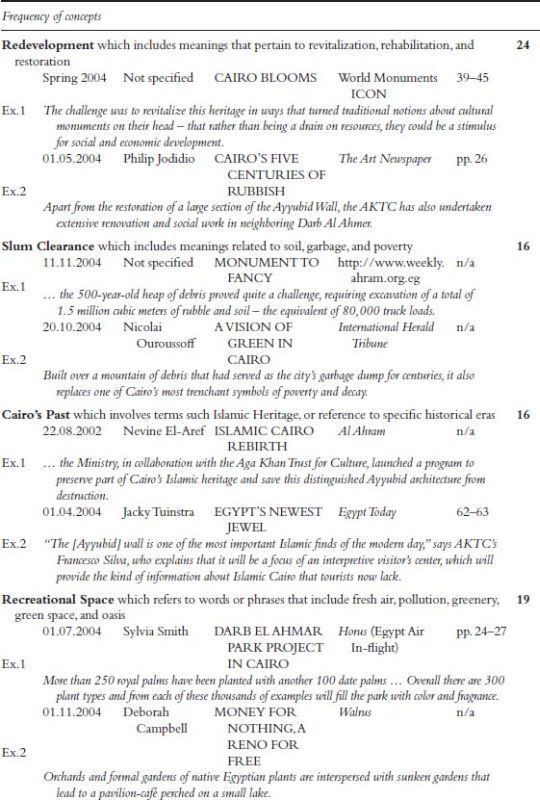

The results convey that the project was portrayed as a ‘Redevelopment’ project where the total frequency of this category appears to be the highest among other established categories as it was mentioned 24 times in the 64 articles and clippings examined. This includes aspects related to rehabilitation, restoration, and such like. The project was also portrayed as a ‘Recreational Space’ offering opportunities for the surrounding community and Cairene society at large to perform public activities in a green environment they had missed for decades. The frequency of ‘Recreational Space’ appears as the second category among others where associated issues were stated 19 times. The categories of ‘Slum Clearance’ and ‘Cairo’s Past’ appear to be equally mentioned where the issues and underlying meanings related to them were stated 16 times for each. The ‘Socio-Economic Development’ category occupies the lowest frequency as its underlying issues were stated only 9 times in 64 articles.

FIGURE 8.5 Categories of concepts/terms utilized in the content analysis of media coverage of Al Azhar Park

Source: author.

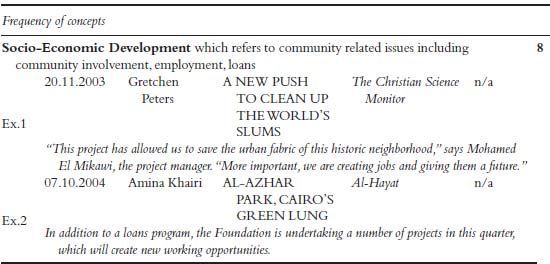

TABLE 8.1 Compelling titles used by the media to project and depict Al Azhar Park

Source: author.

By and large, the project was presented before its completion and was depicted after its occupancy in the media as a sustainable urban conservation intervention that translates cultural, social, and economic needs, hopes, and aspirations into a physical reality. It was dramatically represented as a successful project that addresses multiple issues of concern to the immediate context of Darb Al Ahmar district of old Cairo, to the Governorate of Cairo, and to the Cairene society. Figure 8.5 illustrates all the categories utilized in the content analysis with two examples of articles representing each category. Prominent, catchy, compelling, and powerful article titles were used to attract the attention of the reader to the merits of the project (Table 8.1). Fifteen titles out of a total of 64 appear to be most attractive and involve some powerful messages.

Users’ reactions to Al Azhar Park design qualities

A questionnaire was developed to address key issues emerging from the analysis of the media. It involved users’ reactions to park design, nature of activities, and management issues. Questionnaire forms were distributed by the research team over five visits to the park during the summer of 2005. Responses to closed ended questions were analysed based on simple frequency counts, while content analysis was utilized to evaluate responses to open ended questions. The following analysis is limited only to select key results.

Reactions to the overall planning and design of the park

Rating the overall park design in terms of ‘excellent, good, fair, or bad’ illustrates that the majority of respondents believe that it is either excellent (61.5 per cent) or good (38.46 per cent). While 28 per cent of the respondents have not stated the reasons for selection, those who responded mentioned one or more of the reasons as shown in Table 8.2. Notably, expressing the local culture (22 per cent) and the variety of activities (20 per cent) were the most important reasons for rating the quality of design as excellent or good, while spaciousness (8 per cent) and views (10 per cent) were less important. Twelve per cent of the respondents stated that the relationship between buildings and green spaces is an influential factor for their judgement of design. While the park serves all types of people in terms of socio-economic and cultural backgrounds, their selections and the reasons for those selections exhibit the fact that the park is visited by enlightened users who are able to comprehend the environment in which they live. When people were asked to comment on the park as an urban intervention, and whether it has promoted cultural awareness of Cairene heritage, and whether it has impacted the surrounding community positively, 42 per cent agree with these statements, but 18 per cent do not see the connection and look at the project as a separate entity that does not support recreation and entertainment.

Key places from users’ perspective

Selecting the best place for users to spend their time when they visit the park, the majority of the respondents selected both the gardens and fountains leading off from the main spine (31 per cent) or lakeside café (20 per cent). Those who have selected gardens and fountains as their best place stated one or more of these reasons: they are quiet and private settings, relaxing, and peaceful. On the other hand, those who have selected the lakeside café elaborated more and stated one or more of the following reasons: the freedom of choice to sit in a private area, or by the lake, or closer to more noisy and vibrant spaces; the intimacy of spaces; spectacular views; and the variety of tiling patterns.

TABLE 8.2 Reasons for users’ ratings of the park design as excellent or good

Reasons for users’ rating | Percentage |

The design brings Arabian influence and utilizes greenery very well with fountains … Design is not borrowed from somewhere in Europe or America | 22 |

Variety of green areas, caf és, and the availability of different types of settings | 20 |

The design of buildings is simple and is in harmony with the landscape | 12 |

It is a spacious and beautiful place | 8 |

It offers nice views to the old city | 10 |

No response | 28 |

Source: author.

It appears that the hilltop restaurant and the amphitheatre were the least preferred places from the perspective of the respondents as they were selected by only 6 per cent and 4 per cent respectively. Spending time along the main spine appears to be of equal interest with the children’s play area where each was selected by 12 per cent of the respondents, while the green space adjacent to major facilities was preferred by 15 per cent. In this respect, it was expected that the children’s play area and the amphitheatre would be of more interest to the respondents as the majority of the visitors are families with children.

Best design feature as viewed by park visitors

A number of design features were presented in the survey questionnaire, and respondents were asked to select one best feature available within the park. It is noted that about 6 per cent did not respond to the question. In addition, 7 per cent could not make one choice and selected more than one design feature; therefore their response was not considered valid.

The presence of gardens and water bodies and the gardens around the main spine appear to be the best design features as viewed by the users; each was selected by approximately 22 per cent of the respondents. Views to cultural attractions and the presence of cafés seem to occupy the second level of preference where each was selected as the best design feature by 16 per cent of the respondents. The main spine itself was the least preferred design feature as only 11 per cent selected it as a best design feature.

Regarding the best feature, those who have selected gardens and water bodies, and the gardens around the main spine as best design features, stated one or more of these reasons: adds another dimension to the beauty of the park; gives the feeling that the weather is cooler and temperature is lower during the summer; excellent treatment for Cairo’s climate; well spread throughout the park; adds to the overall relaxing mood; offers more refreshing atmosphere.

A shared interest across the majority of respondents who have selected views to cultural attractions as the best feature was that the park should be a major or the first place Cairo tourists should go to; it is a perfect introduction for them to old Islamic Cairo before they get closer to it. Moreover, a considerable percentage (44 per cent) stated that the dramatic scenic view to Cairo Citadel and Mohamed Ali Mosque and its minarets was a reason for their choice. On the other hand, those who have selected the major spine mentioned one or more of these reasons: spending relaxing time for chatting with family and friends; and children can play in wide green flat areas around the spine, but in close proximity to where their parents sit.

Wayfinding and signage system

Responding to the question about the way in which visitors find their way around the park, 30 per cent stated it is difficult for them to find their way and/or to know their position within the park, while 10 per cent and 50 per cent mentioned it is very easy or easy respectively. These responses relate to another question on how they value the design of signs and the signage system as 33 per cent valued signage as ‘bad’, while 36 per cent said it was ‘fair’. Some of the comments of those who valued signage and sign design as ‘bad’ included one or more of the following reasons:

• The only visible sign in the lakeside café area is inside the café but there are no maps or signs near its entrance.

• There is a need to have ‘you are here’ maps.

• Size of lettering is small compared to the size of some signs.

• Because lettering is too small we do not rely on the signs.

• The problem is at night where signs are not easily seen.

• We started to become familiar with the park after our first visit, but first time we came we were confused.

• Signs are not well distributed in the park.

• While signs are neatly designed they do not satisfy their purpose.

Lights and lighting system

Assessing the lights and lighting system, it is noticed that ‘excellent’, ‘good’, and ‘fair’ are equally attributed by the respondents whereby 20 per cent is given to each of these qualities. However, 35 per cent appear not satisfied with lights as a major design aspect and have given one or more of the following reasons:

• Lights are not good, especially near steps and water channels.

• The level of lighting in most cases, especially in lighting posts, is at the eye level which is disturbing.

• The areas behind the lakeside café and the side of the hilltop restaurant are not well lit.

• You can see the source of lights only, not the surroundings.

• Lights block vision; you feel they are in the way of viewing the whole location.

• Some places are scary as they are completely dark.

Visiting patterns and users’ activities

The majority of the visitors come with their families (64 per cent) and fewer with friends (31 per cent). Visiting patterns appear to be very different across the year. During the autumn and winter seasons 55 per cent stated that they visit the park in the afternoons during the week or at the weekends; 24 per cent stated weekend mornings, while only 16 per cent stated weekend nights. In the spring and summer seasons 50 per cent stated that they visit the park on either weeknights or weekend nights, while 30 per cent visit in late afternoons during the week or weekends, and only 9 per cent stated they visit in the week mornings. Strikingly, none of the respondents stated that they visit the park during weekend mornings. Across the respondents, it is evident that the majority either prefer nights or late afternoons to visit the park.

TABLE 8.3 Activities people perform when visiting the park

List of activities | Frequency and percentage |

Walking (along the main spine) | 34 (06.71%) |

Dining in hilltop restaurant | 23 (04.53%) |

Dining in lakeside café | 56 (11.04%) |

Contemplating while sitting in any open or semi-open areas | 47 (09.27%) |

Chatting with family and friends | 91 (17.92%) |

Sitting in isolation under one of the gazebos distributed throughout | 32 (06.30%) |

Sitting in one of the gardens off of the main spine | 87 (17.10%) |

Playing with children in one of the green spaces off of the main spine | 72 (14.20%) |

Playing with children in the children’s play area | 49 (09.66%) |

Attending a concert or public performance | 16 (03.16%) |

Total # of frequencies | 507 (99.89%) |

Source: author.

The preceding visiting patterns correspond with the results of selecting gardens and water bodies and gardens around the main spine as the best design feature. Such patterns corroborate the results of the continuous visits to the park by the research team during the summers of 2005, 2006, and 2007, which reveal that the park is completely vacant in the mornings and early afternoons. Over 80 per cent of the respondents believe that the design of the park allows for many activities that family members can perform during their visits. The majority agree that there are special places developed to satisfy all age groups including restaurants, greenery, and children’s play areas. Selecting three major activities performed while visiting reveals a wide range of interests and activities that the park is accommodating as illustrated in Table 8.3.

Certain activities appear to be favoured by the respondents; these include chatting with friends (17.92 per cent); sitting in one of the gardens off of the main spine (17.10 per cent); and playing with children in one of the green spaces off the main spine (14.20 per cent). Dining in the lakeside café appears to be favoured over dining in the hilltop restaurant (4.53 per cent). These results correspond with the results of favouring views and seeing the gardens and fountains around the main spine as key attractions within the park. They also indicate that the presence of the lake is a determining factor in people liking the southern portion of the park.

Management and operation

By utilizing a five-point scale, people were asked to express their degree of satisfaction with the management and operation of the park. The majority of the respondents are either very satisfied (29 per cent) or satisfied (53 per cent). Only 4 per cent have expressed dissatisfaction and 8 per cent were neutral. None of the respondents stated that they were very dissatisfied. Respondents commented positively on the cleanliness and neatness of the park. However, a few (4 per cent) commented that the marble tiling in the garden areas is starting to show signs of deterioration.

As it is known to the public that the park is managed by a private service company, users were asked whether they support the idea of the management of the park being transferred under the jurisdiction of Cairo Governorate in terms of management, maintenance, and operation. Eighty-seven per cent of the respondents stated that they are not advocates of this idea at all. While this result is striking, it was expected, since some respondents introduced assertions like: ‘the park will deteriorate with public government ownership’, ‘because typically government facilities often deteriorate, and there are many examples of similar projects’. Some went to the extreme and commented ‘because they will mess it up’, and ‘there is a very big chance that the park would go back to its original use, a dump site’. These statements reflect a severe lack of trust in the government’s ability to run and manage large public projects.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, an examination of the media, especially that which celebrates large influential projects, is important in order to understand the type and validity of information it conveys to the wider audience. Scrutinizing the assumption that projects celebrated in the public or specialized media are not necessarily meeting users’ expectations or satisfying their needs revealed both satisfactory and critical results that were never covered in the media.

The media still give little attention to users’ behaviour and feedback on needs and expectations. Nevertheless, the content analysis of the literature written to describe and praise the project illustrates that there are attempts towards more responsiveness to real and pressing issues including protection of the built heritage, slum clearance and environmental concerns, and socio-economic development aspects. Despite this the media fell short in articulating users’ feedback, cultural behaviours and attitudes, and addressing the concerns of the users. In addition, spatial quality appears not to be a major concern including its underlying symbolic, behavioural, and experiential aspects. Findings indicate that users’ reactions to the design features of the park correspond with the way in which the project is celebrated in the media. To relative degrees, users expressed their satisfaction with the park environment, the available amenities, and with the available opportunities to engage in a wide spectrum of activities.

The fact that most planning and design aspects of the park were satisfactory to – and in some cases were praised by – the users is an indicator of the degree of the project’s success. Two design features seem to fall short in meeting users’ expectations. These are the lights and lighting system, and the signage and the wayfinding system. While these two aspects were not well covered by the media, they were unveiled through analysing users’ feedback. In fact, the lights and the lighting system were portrayed in the media through photographs that emphasize the dramatic visual effects of the lights used in the park, but functional and experiential aspects were the concern of the users. While scholars may claim that no planning or design outcome is completely perfect and satisfies everyone, one should assert that a project of this scale, magnitude, and amount of recognition is not expected to have these aspects as major sources of dissatisfaction. Notably, the media have not addressed the issue of operations and maintenance, an aspect that can only be revealed by a post-occupancy evaluation (POE, see Chapter 14). In this respect, while users expressed satisfaction with the current operation and maintenance, the results corroborate a severe lack of trust in the government to manage and operate the park.

It should be noted that the method of conducting assessment studies based on attitude surveys has a limitation since it explains behavioural or attitudinal phenomena based on what is being stated rather than on what is actually happening. Conducting appraisals relevant to the actual performance of the park as witnessed in users’ behaviour can further invigorate the type of investigation employed in this study. Adopting the habitability framework outlined in the introduction (see Chapter 1) of this book or elements of it would contribute to a better understanding of how aesthetic and performative aspects of the park may complement each other. By utilizing social science research tools, including behavioural and cognitive mapping and systematic observations, deeper insights into human behaviour in and satisfaction with the environment can be unveiled.

Corresponding with contemporary literature (Sanoff 1991; Preiser and Nasar 2008; Davis and Preiser 2012) the investigation reveals that the habit of criticism continues to contribute to generating subjective viewpoints about the built environment. While post-occupancy evaluation represents a dramatic departure from typical subjective discussions, it paves the road towards the development of theory and practice. One should assert, however, that it is not a situation of either/or; criticism and evaluation are both needed in the development of a responsive environment while improving the quality of design decision-making at different levels.

References

AKTC (Aga Khan Trust for Culture) (2001) The Azhar Park Project in Cairo and the Conservation and Revitalization of Darb al-Ahmar. Geneva: AKTC-Historic Cities Support Program.

Davis, A. T. and W. F. E. Preiser (2012) ‘Architectural Criticism in Practice: From Affective to Effective Experience’. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 6(2): 24–42.

Nasar, J. L. (1986) ‘The Shaping of Design Values: Case Studies on the Trade Magazines’. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the Environmental Design Research Association. Atlanta, GA: EDRA Publications.

Preiser, W. F. E. and J. L. Nasar (2008) ‘Assessing Building Performance: Its Evolution from Post-Occupancy Evaluation’. ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2(1): 84–99.

Rapoport, A. (1970) ‘The Study of Spatial Quality’. Journal of Aesthetic Education 4(4): 81–95.

Salama, A. M. (1995) New Trends in Architectural Education: Designing the Design Studio. Raleigh, NC: Tailored Text and Unlimited Potential Publishing.

Salama, A. M. (2008) ‘Media Coverage and Users’ Reactions: Al Azhar Park in the Midst of Criticism and Post Occupancy Evaluation’. METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture, Middle East Technical University, 25(1): 105–25.

Sanoff, H. (1991) Visual Research Methods in Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.