MID-OCCUPANCY URBANISM IN SHANGHAI

The current state of the site of Expo 2010

Introduction

The site of Expo 2010 Shanghai China is in the middle of its transition from a land of make-believe to a key new area of the city. Of the 145 buildings that made up the expo, only five were built to be permanent.1 Yet three years after the world’s fair, 99 temporary buildings remain. Some continue to promote the countries that built them. Others have been converted into theaters, museums, and theme parks. Still others stand firm but empty, awaiting reuse or demolition.

The Expo buildings could be viewed as anomalies, architectural follies that have little relevance to the more serious development of greater Shanghai. But the former Expo site could also be read as a microcosm of the city. As in other parts of Shanghai, a number of factors converge to result in the reuse of some buildings and the demolition or disuse of others. This chapter looks at the Expo site in the middle of its redevelopment to explore these factors.

Expo 2010

Expo 2010 Shanghai China took place between May 1 and October 31, 2010. The world’s fair, organized under the theme “Better City, Better Life,” covered 5.28 square kilometers formerly occupied by factories, residences, and a vast shipyard on both sides of Shanghai’s Huangpu River.2 Its more popular venues – the national pavilions and the main event spaces – were south of the Huangpu in the newly developed part of the city called Pudong. Corporate pavilions and the Urban Best Practices Area were positioned in Puxi, north of the river. Both sites are three kilometers south of Shanghai’s center, where Puxi’s Bund faces Pudong’s Lujiazui across the river.

Expo 2010 came on the heels of the hugely successful Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. While the Olympics aimed to show China to the world, Expo had the opposite intent – to show the world to China. Only 5.8 percent of the record-breaking 73 million visitors were foreigners.3 The 246 participating countries and international organizations spared no expense in this show. France exhibited original artwork by Van Gogh, Manet, and Millet; Chile displayed a capsule designed to rescue the Copiapó miners; and Denmark brought the actual Little Mermaid, a statue and national treasure, from the Copenhagen harbor to Shanghai.

FIGURE 16.1 Footprint of buildings during Expo 2010 Shanghai China. The Huangpu River runs between buildings in Puxi (to the north) and Pudong (to the south). The five buildings designated to be permanent structures are (1) Expo Axis; (2) Expo Center; (3) Expo Culture Center; (4) Theme Pavilion; and (5) China Pavilion.

Source: Clare Jacobson.

Countries showed themselves to China not only in what they brought to Expo but also in the buildings that housed these wonders. Well-known architects – including Norman Foster (United Arab Emirates Pavilion) and Miralles Tagliabue EMBT (Spain) – designed national pavilions. Designers with less global recognition – such as Vo Trong Nghia (Vietnam), John Körmeling (The Netherlands), and Juan Carlos Sabbagh (Chile) – produced sublime pieces of architecture as well. Cities and corporations were also well represented in pavilions by Wang Shu (Ningbo) and Yung Ho Chang (Shanghai Corporate).

Thomas Rohdewald, Director of the Luxembourg Pavilion, talks about his country’s participation in the fair.4 Luxembourg, he says, does not attend every world expo but decided to join Expo 2010 in order to increase its recognition in Asia. In Shanghai, Luxembourg built its largest-ever world expo pavilion, in both size and budget. Rohdewald says a combination of good architectural design, curiosity about his small country, the inclusion of Luxembourg City’s original Golden Lady statue, and a free-flowing rather than periodic entrance led to 7.2 million visitors. This is 10 percent of the total number of Shanghai Expo visitors, up from 5 percent at the 2000 Expo in Hanover, Germany. According to the Luxemburger Wort, the pavilion had another benefit: it garnered business revenue of €5.8 million ($7.8 million).5 Coincidentally or not, applications for C visas from China to the Schengen Area, of which Luxembourg is a part, increased from 597,430 in 2009 to 1,079,516 in 2011.6

FIGURE 16.2 Footprint of buildings on July 12, 2013. Buildings in black are in use; those in gray are extant but not in use. The five permanent buildings are now (1) River Mall; (2) Shanghai Expo Center; (3) Mercedes-Benz Arena; (4) ICBC World Expo Exhibition and Convention Center; and (5) China Art Museum. Other buildings and collections of buildings in use are (6) Saudi Arabia Pavilion; (7) Expo Stage (formerly Baosteel Stage); (8) Energy Park (Turkey, Ukraine, and Iceland pavilions); (9) Shanghai Italian Center (Italy and Luxembourg pavilions); (10) Shanghai Expo-Mart (Africa Joint Pavilion); (11) Chocolate Happy Land (South Africa, Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, Angola, Nigeria, Libya, Argentina, and Slovenia pavilions and an information center/toilet); (12) Gung Ho Communications Office (Cuba Pavilion); (13) information center/toilet; (14) Commemoration Exhibition of Expo 2010 Shanghai China (Pavilion of Urban Footprint); (15) PICC Pavilion; (16) Shanghai Children’s Theater (SAIC-GM Pavilion); (17) Power Station of Art (Pavilion of Future); (18) Macao, Rhône-Alpes, Alsace, Hamburg case pavilions, with revised public and private uses; (19) SKF Shanghai Office (Cases Joint Pavilion 2).

Source: Clare Jacobson.

Post-Expo buildings

The splendor of Expo was not meant to last. Pavilions were designed to stand for six months in Shanghai, and thus avoided the construction necessities that cold winters and long-term resiliency would require. Only five Expo structures – Expo Axis, Expo Center, Expo Culture Center, Theme Pavilion, and China Pavilion – were built to be permanent. According to Huub Buise, Consul, Consulate General Kingdom of the Netherlands, Expo documents stated that the Dutch Pavilion had to be demolished by May 31, 2011.7 It was the responsibility of each country to remove its national pavilion to meet this deadline.

Some building owners responded quickly to their contractual duty. The UK demolished its “Seed Cathedral,” designed by Thomas Heatherwick, soon after the fair closed, dispersing its seed-filled acrylic rods to Chinese schools and through an online sale.8 The building was much loved by visitors and critics alike, and it received Expo’s Gold Pavilion Design Award. When asked why it was not saved, David Martin, Deputy Director of the UK Pavilion, says that it was meant to be a temporary thing, “more lasting in its memory than … in its reality.”9

Some pavilions were designed so that they could be taken down easily and reconstructed on other sites. The UAE sent its Foster-designed building back home, where it is used for the Abu Dhabi Art Fair.10 Other countries looked to rebuild their pavilions in China. The Sweden Pavilion was taken apart and transported to Hebei Province to be part of the Tangshan Caofeidian Ecocity.11 It remains in storage as of summer 2013, “due to lack of funds in the city.”12 The Finland Pavilion was specifically designed to allow it to be reconstructed at another site, but since reconstruction was not realized, “most of its materials were recycled in a sustainable way.”13 The profit of recycling in China makes it likely that materials from this and other demolished buildings were reused.14

In the summer of 2013, long after the May 2011 deadline, many Expo national pavilions – as well as other Expo buildings – remain present on site for a variety of reasons. Some are being reused. The Cuba Pavilion now houses offices for Gung Ho Communications, and the Africa Joint Pavilion is now the Shanghai Expo-Mart, an exhibition center. Other buildings sit abandoned, showing the wear of three years. Portugal’s cork façade has been stripped as if a tree, the Czech Republic has lost its hockey pucks, and all the red flags that covered Croatia have blown away.

The former Expo site is now a patchwork of three-year-old pavilions, fenced-off rubble-strewn plots, and big digs for new developments. I mapped this site in the summer of 2013, three years after Expo, to gauge the changes (Figures 16.1 and 16.2). As the status of the area is changing quickly, I chose the date of July 12, 2013 for this mapping. Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition at the spruced-up former Greece Pavilion closed just before this date, and the Aviator Theme Park at the site of the US Pavilion held a trial opening soon after. But this mapping shows the footprint on a single day.

Planning the Expo site

“Patchwork” may not be the ideal word to describe the current footprint of Expo 2010 Shanghai China. The buildings on the Puxi site, in fact, remain largely intact. Those on the Pudong side are patchier, but their presence and absence fall mainly according to the location in which they sit.

This is no happy coincidence. The post-Expo redevelopment plan is a somewhat expanded but otherwise minimally changed version of the original Expo plan. And the state-owned investment enterprise in charge of the new plan, Expo Shanghai Group (ESG), under the supervision of the Shanghai Municipal Government, is essentially a continuation (albeit on a smaller scale) of the Shanghai Expo Bureau, which coordinated the preparation and operation of Expo.

Jasmine Pang, Spokesperson, Deputy GM of General Office, ESG, says the planning bureau needed to have a vision for the post-Expo use of the site because the area would take the lead in new city development. She notes that the Shanghai Expo differs from previous world expos because it is built within the city, not in the outskirts. After Expo, 225 hectares (roughly half of Expo’s 528 hectares) were available to be reused and redeveloped. Of this, 78 hectares are to be redeveloped and 147 newly developed.15

Most of the empty Pudong lots are concentrated around Expo’s five permanent buildings. It is an active center. The China Pavilion is now reused as the China Art Museum, currently China’s largest art museum. Expo Culture Center, now the Mercedes Benz Arena, has held concerts by Jennifer Lopez, the Beach Boys, and Metallica. The renamed Shanghai Expo Center and ICBC World Expo Exhibition and Convention Center hold conventions ranging from “Architects@Work” to boat shows. The 1,000 × 110 meter Expo Axis is in the process of becoming the River Mall. A few small shops and metro stops at either end of it help to service the buildings around it.

FIGURE 16.3 Site map of five zones during Expo 2010 Shanghai China. The predominant uses for the zones are (A) Asian and Middle Eastern national pavilions; (B) Five permanent buildings, Southeast Asian national pavilions, and pavilions for international organizations; (C) African, European, and American national pavilions; (D) corporate pavilions; (E) Urban Best Practices Area.

Source: Clare Jacobson.

FIGURE 16.4 Site map of future use of five zones, as defined by the Expo Shanghai Group, March 2013. The zones are designated as (A) Governmental Office Community; (B) International Exhibition and Central Business District Area; (C) Houtan Extended Zone; (D) Museums and Exhibition Zone; (E) Urban Best Practices Area.

Source: Clare Jacobson.

Ground has been broken on sites east and west of this center, which have been cleared of Asian and Middle Eastern national pavilions. (The only pavilion to remain in this area, and the only foreign national pavilion designed by a Chinese architect, is the $164 million Saudi Arabia Pavilion, the most expensive pavilion at the fair.16) Of the handful of new projects that are under construction, the farthest along is by Atlanta-based architect John Portman. His complex of four hotels covers a 300,000 square meter site just south of the ICBC Center.17

These new developments follow the economics of Shanghai development, where large parcels of land are commonly sold as one site. Planning for the area formerly occupied by factories, residences, and a shipyard seems to have paid off. According to China Daily, in the spring of 2013 a 6,100 square meter plot in the former Expo area was sold at a record-breaking ¥40,079 ($6532) per square meter.18

Redevelopment in Pudong

Despite this record-breaking land value, many national pavilions remain in Pudong (Figures 16.3 and 16.4). In early 2011, it was reported that five national pavilions – France (designed by Jacques Ferrier Architectures), Italy (Giampaolo Imbrighi), Russia (P.A.P.er architectural team), Spain (Miralles Tagliabue EMBT), and Saudi Arabia (Wang Zhenjun) – had been donated to Shanghai and would reopen soon.19 In October 2011 the Luxembourg Pavilion (Hermann & Valentiny) joined this group.20 All six have drawn attention in the design press, appearing on ArchDaily, Dezeen, Designboom, and other popular sites, and all but Italy received one of the official 34 awards at Expo 2010.21 Yet it is difficult to measure how these pavilions’ design and their popular reception influenced their retention.

While plans to put these six pavilions into operation continue, only three – Saudi Arabia, Italy, and Luxembourg – had reopened as of summer 2013.22 People who skipped the Saudi’s nine-hour line can now see roughly the same show for a single-venue price.23 And Italy has absorbed the Luxembourg Pavilion (now used as Istituto Marangoni fashion training center and the Da Marco Restaurant) and The Netherlands Pavilion (which is empty but supports a video screen showing Italian content) into the Shanghai Italian Center.24 The center – in partnership with Ferrari, Bulgari, and several other Italian brands – reopened on May 18, 2012 as an exhibition and cultural center and as a showplace for Italian products.25 A ticket office, information center, and gift shop have been added to the complex, and the area where the UK Pavilion stood is now used as its parking lot. Ferdinando Gueli, Deputy General Manager, Shanghai Expo Trade Co. Ltd, Shanghai Italian Center, says the center had 400,000 visitors in its first year, more than the annual visitation to Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper in Milan and the Medici Chapels in Florence.26

Across the street from the Shanghai Italian Center, the pavilions of South Africa, Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, Angola, Nigeria, Libya, Argentina, and Slovenia have been converted to Chocolate Happy Land, a theme park. No one could argue that these buildings were saved for their architectural value. They are stock cookie-cutter boxes built by the Expo and rented to participating countries.27 (In fact, 75 percent of Expo participants exhibited in rented or joint pavilions.)28 What the buildings have that made them worth saving was their uniformity (which made them easy to reuse) and their proximity to the Shanghai Italian Center and Shanghai Expo-Mart (which makes them easy to access). One public bus stop serves all three sites.

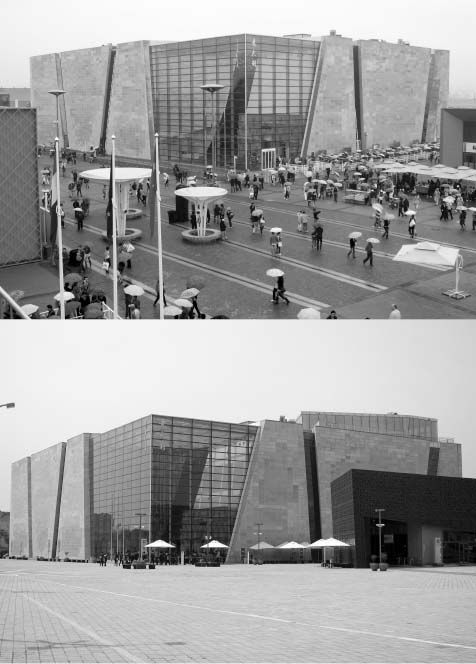

FIGURES 16.5 Italy Pavilion during Expo 2010 (top) and with a new information center for reuse in the Shanghai Italian Center during the summer of 2013 (bottom)

Source: Clare Jacobson.

FIGURES 16.6 Angola Pavilion during Expo 2010 (top) and redecorated and reused as part of the Chocolate Happy Land theme park during the summer of 2013 (bottom)

Source: Clare Jacobson.

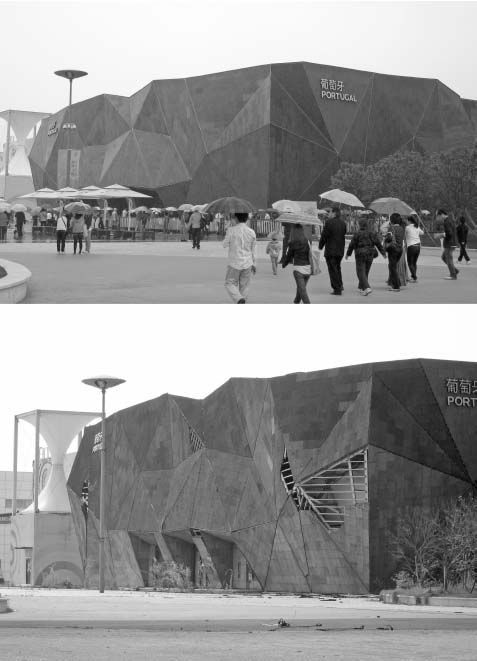

FIGURES 16.7 Portugal Pavilion during Expo 2010 (top) and extant but unused during the summer of 2013 (bottom)

Source: Clare Jacobson.

The Turkey Pavilion, another award-winning project, is now the headquarters of Energy Park. Together with the Ukraine and Iceland pavilions, it forms a theme park with a track for riding electric cars, electric go-karts, and Segways. Asked how the design might have influenced the retention of the building, Deniz Eke, Consul General of Turkey, says that she is not sure, “But if you ask my personal and non-expert opinion, I may agree that the architectural design of our pavilion, or more so the story behind it, may have influenced this decision.”29 The pavilion’s dark red and white exterior – meant to represent the volcanic mountain, Hasandağ, and houses in Çatalhöyük – has been repainted white and bright green to suit its new use.30

Elsewhere on the Pudong Expo site, the Denmark Pavilion sits among several similarly unused remnants of Expo. Stine L. Guldmann, Project Director of Expo Association Denmark, explains, “When Expo 2010 closed, the Chinese Expo organizers asked to take over the raw pavilion in order to delay the dismantling, so that the area wasn’t left as one big building site at once.”31 The Venezuela and Mexico pavilions appear as contenders across a newly built soccer field, which replaced the Chile Pavilion. A trio from Spain, Serbia, and Monaco stand next to each other, their wicker or brightly colored façades faded to dull tones. Not far away, the Porterhouse, an Irish brewpub and one of the few stand-alone restaurants at Expo, sits alone in a field, its taps long shut down. While construction crews are busy around Expo’s center, it will take some time for them to arrive to the western frontier where these buildings remain (Figures 16.5, 16.6, 16.7).

Redevelopment in Puxi

Across the Huangpu River in Puxi, a similar footprint of demolished sites, remnant buildings, and reused buildings exists. On this smaller site, fewer buildings are in use. The SAIC-GM Pavilion is now the Shanghai Children’s Theater, and the Pavilion of Urban Footprint now holds the Commemoration Exhibition of Expo 2010 Shanghai China.

The most active Pudong area is the Urban Best Practice Area (UBPA). This small development showcased city initiatives such as Taipei’s trash recycling, Macao’s reuse of historic buildings, and Madrid’s low-income high-design housing. The Power Station of Art, China’s first state-owned museum of contemporary art, anchors the UBPA. Its building was used as the Pavilion of Future during Expo 2010, and was originally a power station.

Many of the UBPA case studies were similarly shown in reused industrial buildings, which are being reused again. Case Joint Pavilion 2 now holds the SKF Shanghai Office, and cases Joint Pavilion 4 is being converted to a “Cultural Experience Center.” The UBPA development is focusing on accommodating creative industries, according to Dr. Tang Zilai, Professor and Head, Department of Urban Planning, Tongji University and Chief Planner of UBPA.32

Some stand-alone UBPA constructions remain in use. The Macao, Rhône-Alpes, Alsace, Hamburg case pavilions now have revised functions, including city-specific offices, restaurants, and product showrooms. A garden representing Chengdu sits in the middle of them. UBPA’s new buildings and the Chengdu garden are partial or full-scale reproductions of precedents. UBPA contains other copied contributions, including an Antoni Gaudí lizard, a gift from Barcelona. Tang notes that the UBPA’s main square duplicates the L shape of St. Mark’s Square in Venice.

The proposed future footprint of UBPA is very similar to the footprint of UBPA during Expo. According to Tang, it was decided in the early planning of UBPA that many of the pavilions would remain as permanent buildings. This plan was not announced, he says, as it would have been politically inopportune to do so. But groups of UBPA pavilions were constructed for long-term, rather than six-month, lives, while others were built as temporary structures to allow for high-rise development in their place after Expo. Wang Shu’s Ningbo case Pavilion is one of these temporary buildings. Tang says that since Wang won the 2012 Pritzker Prize, the UBPA is reconsidering moving the building from the redevelopment area and making it permanent.

Conclusion

Three years after Expo 2010 Shanghai China, its buildings exist in a state of mid-occupancy urbanism. A number of factors – including geographic proximity (for example, where buildings stand in relation to the five permanent buildings), economic viability (Italy Pavilion), popular reception (Saudi Arabia Pavilion), and perceived design value (Ningbo Pavilion) – affect which Expo buildings stay, which go, which are used, and which are dormant. Yet the most important factor is the Shanghai Expo Bureau. It predetermined the five Pudong buildings and the UBPA Puxi buildings that would remain permanently, the buildings that needed to be demolished for immediate redevelopment, and those that could remain in a state of limbo until development arrives.

I began research for this chapter assuming (or, rather, hoping) that extant Expo buildings were saved because of their good design. I found that in fact single buildings had little import within the site’s master plan. The same can be said of the development of greater Shanghai, outside the Expo site. Few single buildings have been preserved. Instead, Shanghai’s historic architecture tends to exist in clusters – the Bund, Xintiandi, Red Town, Tianzifang – that are economically viable as destination neighborhoods. As fewer and fewer heritage buildings remain in Shanghai, those interested in saving what is left might start thinking less like preservationists and more like planners. The key to retaining old Shanghai may be saving it in bulk.

Notes

1. Bureau of Shanghai World Expo Coordination, Expo 2010 Shanghai China Official Guidebook (Shanghai: China Publishing Group, 2010). Additional building data used in this chapter are based on site visits by the author during Expo 2010 and during the summer of 2013.

2. Shanghai Guidebook; David Barboza, “Shanghai Buys Itself a Makeover Before a Fair,” New York Times, May 30, 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/31/world/asia/31expo.html

3. David Barboza, “Shanghai Expo Sets Record with 73 Million Visitors,” New York Times, November 2, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/03/world/asia/03shanghai.html

4. Thomas Rohdewald, interview with author, Shanghai, July 10, 2013.

5. “Shanghai Expo Pavilion Earns €5.8 Million for Luxembourg for Business,” Luxemburger Wort, July 23, 2012, http://www.wort.lu/en/view/shanghai-expo-pavilion-earns-5-8-million-for-luxembourg-for-business-500d71fae4b0957b2af2b6e7

6. European Commission Directorate-General Home Affairs, “Overview of Schengen Visa Statistics 2009–2011,” http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/borders-and-visas/visa-policy/docs/overview_of_schengen_visa_statistics_2011_final_en.pdf

7. Huub Buise, interview with author, Shanghai, August 10, 2013.

8. Clare Jacobson, “Setting the Bar High: The UK Leaves an Indelible Legacy at Expo,” The Beat (December 2010).

9. Ibid.

10. Susan Hack, “Abu Dhabi Art Fair Guide: What to See, Where to Eat, and How to Get Around,” Condé Nast Traveler, November 7, 2012, http://ww.cntraveler.com/daily-traveler/2012/11/abu-dhabi-art-fair-saadiyat-island-guide

11. Peng Lin, “Introduction of Tangshan Caofeidian Ecocity,” PDF document dated October 2011, emailed to author.

12. Britt Lindner Norberg, Project Manager of CENTEC, Embassy of Sweden, email to author, August 23, 2013.

13. Clare Jacobson, “At Shanghai Expo, Finnish Pavilion Provides a Stunning Green Model,” Engineering News Record, September 6, 2010, http://enr.ecnext.com/coms2/article_bude100901ShanghaiExpo; Eili Andersson, Consul, Consulate General of Finland, email to author, September 13, 2013.

14. For more on the economics of recycling in China, see Adam Minter, Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2013).

15. Jasmine Pang, interview with author, Shanghai, July 25, 2013.

16. Hart Cohen, “Culture, Nation, and Technology: Immersive Media and the Saudi Arabia Pavilion,” in Tim Winter (ed.), Shanghai Expo: An International Forum on the Future of Cities (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), pp. 155–69.

17. “Expo Hotel Complex,” John Portman & Associates, http://www.portmanusa.com/projectdescription.php?name=Expo%20Hotel%20Complex&projectid=5940, accessed September 10, 2013.

18. “Commercial-Property Price Record Set in Shanghai,” China Daily US Edition, May 9, 2013, http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2013-05/09/content_16489569.htm

19. “Five Foreign Pavilions to Remain at Expo Site,” Global Times, January 4, 2011, http://www.globaltimes.cn/shanghai/society/2011-01/608593.html

20. “Pavilion a Present,” Luxemburger Wort, October 21, 2011, http://www.wort.lu/en/view/pavilion-a-present-4f60c217e4b047833b93a091

21. Chen Ran, “Expo Pavilions Commended,” Beijing Review, October 31, 2010, http://www.bjreview.com.cn/expo2010/2010-10/31/content_309498.htm

22. ESG’s Jasmine Pang mentions the France Pavilion will reopen as an art museum, Spain as a Spanish cultural center, and Russia as a yet-to-be-determined venue. Pang, interview with author.

23. Cohen, “Culture, Nation.”

24. Huub Buise, says the Netherlands made a deal with the Expo corporation to keep the building, stating the project must not be used for commercial ventures and must be removed by December 2015. Buise himself is not certain that this date will be held, stating it is more likely to change with new government in 2020. Buise, interview with author.

25. Shanghai Italian Center, PDF document dated June 13, 2013, emailed to author.

26. Ferdinando Gueli, conversation with author, Shanghai, July 15, 2013.

27. Consulado General de la República Argentina en Shanghái, email to author, August 5, 2013.

28. Willem Paling, “Ordinary City, Ordinary Life: Off the Expo Map,” in Winter (ed.), Shanghai Expo, pp. 120–36.

29. Deniz Eke, email to author, July 9, 2013.

30. EXPO Theme “Better City, Better Life,” Turkey Expo 2010 Shanghai, http://www.turkishpavilion2010.com/en/, accessed September 17, 2103.

31. Stine L. Guldmann, email to author, September 17, 2013.

32. Dr. Tang Zilai, interview with author, Shanghai, August 2, 2013.