6

Models of the Self: ‘Model’ Cottages, Slum Clearance and the Garden City Movement

As part of The Argus newspaper’s Modern Homes Exhibition in 1933, a ‘model’ house was constructed on the stage of the Cape Town City Hall at full scale.1 Occupying centre stage of Cape Town as it did, the house gained an exhilarating ideological charge. More significantly, the exhibition was opened by the flick of a switch in London which lit this particular house up, throwing its light around the City Hall. Apart from the symbolism involved in this particularly English en-lightening of the Cape, it is easy to acknowledge the currents of power running from the metropole to the outposts of the Empire being directly activated by this event. But these were ideological currents too, connecting this house on centre stage with a long line of ‘model cottages’ running all the way back to another exhibition, the Great Exhibition2 of 1851 where Prince Albert placed his own ‘model cottage’ on display near the Crystal Palace. The English had a penchant for cottages, but more importantly, for cottages as models for living – especially for the working class. With the flick of a switch then, we find the agents of Empire in South Africa charged with the task of fulfilling this lineage.

Tellingly, Prince Albert’s model cottage was a fine specimen on public display only a few years before Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Both offered strong positions on the impact that the physical environment has on ‘species,’ whether working horse or working class. Certainly, the notion that the environment had a fundamental effect, good or bad, on an individual was present throughout the age of Empire and its endless production line of ‘model’ cottages. Environmental determinism flipped between the negative influence of the slums and the wholesome world of imagined ‘model’ dwellings and villages where buildings were considered instruments in the process of proper socialization. From the factory-village housing of Bournville and Port Sunlight to the Garden City Movement, the weight of expectation of building a better society began to be increasingly loaded onto the framework of buildings themselves, testing the very foundations of architecture. The strength and development of ‘the Nation,’ the eradication of crime, instructions in ‘civilization,’ as well as civic duty and moral character, were thought to be formed through the dwelling and environment. Even innocuous ‘beauty’ – perhaps the originating disinterested sponsor of architecture – was co-opted into the service of the common good with the belief that it could transform and ‘uplift’ the sensibility of the poorer classes and bring them in line with ‘normal’ bourgeois values.

The intentional effort to socialize people through specific building arrangements and environments is best summarized by the word ‘instrumentality’ which had, in this case of Imperial Cape Town, the desire to universalize and normalize the values of the English middle class. Exactly how this was to be achieved, as we shall see in the examples below, ranged from the notional to the specific; from written representations and graphic visualizations to imagining Otherness away and literal plans structuring the erasure of Otherness. Replaced, of course, by the values of Englishness. Standish Meacham, in Regaining Paradise,3 investigates the way a vision of Englishness informed the products of the Garden City Movement – its Arts and Crafts cottages and medieval villages – and the way those products themselves were intended to strengthen a sense of Englishness. One of the key points he makes is that the Garden City Movement proponents, through their social reform program, were instrumental in the establishment and reinforcement of an English identity that was particularly anti-urban.4 Not only did the Garden City Movement valorize the English rural landscape, but it tended to valorize a pre-industrial landscape in the vein of the historicist visions of Pugin. Again, in Regaining Paradise, Meacham argues that precursor Garden City Movement projects, such as Port Sunlight and Bournville, presented a ‘sanitized and Romanticized version of life as it had been. In their governance and, probably more important, in the way daily life was dominated by the presence of their beneficent founders, they longed for paternalistic hierarchical relationships from the past.’5 With the advent of the Garden City Movement the working classes of England had begun to find themselves the ‘victims’ of a strange vision of modernity that looked to the English medieval past for models and methods – a ready-made social-spatial order – aimed at curtailing their libidinal energy and co-opting them as role-playing extras in the anachronistic scenographic pageantry of Englishness.

So it is not surprising to read in the administrative archives of the City of Cape Town strongly anti-urban, paternalist and hierarchical attitudes in the instrumentalist housing projects orchestrated by the agents of Empire aimed – particularly, but not solely – at the city’s Coloured population. Certainly the desire to produce, through the instrument of housing, a class of people approaching some of the values of the English middle class was a matter of self interest; the notion of ‘class raising’ could help secure a stable labour force and also increase the level of commodity consumption in the population. As the then Archdeacon of Cape Town, Sidney Lavis, noted ‘… a decently housed, physically fit, morally developed coloured community cannot be otherwise than an economic and social gain to the state.’6

Similarly, the Union Government’s Secretary for Labour noted his desire in a letter to the Town Clerk to have the Coloured population of the Peninsula properly housed

with a view to promoting conditions which will tend to raise it in the scale of civilisation. It is the belief of the Council that the coloured population, if not throughout all sections, at least in a good many sections, has in it the makings of a good class of citizen, and that all sections can be definitely raised under more favourable conditions of housing and other social and educational considerations.7

‘More favourable conditions of housing’ indeed. In 1925 the Woodstock magistrate declared: ‘Crime in the Peninsula was largely due to bad housing,’8 and went on to state that: ‘I am certain that healthy housing has saved many a youth from being inoculated with a virus which has led to his becoming a charge upon the criminal administration of the State. By permitting the contrary, we are sterilising better stocks, increasing low types, and impoverishing national fitness.’

Notwithstanding the imperatives of ‘enlightened self-interest’ the tinges of eugenic ‘sterilizing’ in the magistrate’s tirade brings the ‘housing question’ out of simple instrumentalist ambitions and back into the realm of Englishness and the play of identity politics. As I have shown in the previous chapter, parts of Old Cape Town were considered places of disorder and a threat to the emerging racial order of South Africa. As the ‘mother city’ Cape Town had long had a reputation as a cosmopolitan town with supposedly9 liberal attitudes to race, largely, due to the close relationship between Coloureds or its creole population and the original colonizers. But the territorially-embedded history of these people within the space of the city undermined the agents of Empire’s hardening taxonomies of race and order. The literal and figurative proximity of places such as District Six, and its racially mixed inhabitants, to the centre of Cape Town threatened the tenuous dominance of the colonizers and the hierarchically-ordered project of Empire. The city’s Others needed to be reorderd into a state of being more in alignment with the coordinates of Englishness, into a state less threatening to the values of Englishness. And the city itself needed to be dismantled and reconstructed into a set of suburbs in alignment with the taxonomies of race and order.

What follows is an exploration of how the anti-urban values of Englishness were inscribed into the surface of the city in projects both real and imagined. Our closing engagement with these values of Englishness is an investigation into what constituted – and what did not constitute – the models of the Self and, most importantly, their impact on the remaking of the domestic space of Cape Town into suburbia and thence the remaking of the city’s Others into a more neutered Same.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO THE HOUSING PROBLEM

Of course I am not underplaying how issues of health were used to legitimize the early racial segregation of cities in South Africa10 initially with the plague in 1901 and the Spanish ’flu pandemic in 1918. These events punctuated a growing sense of unease for the agents of Empire that there was a threatening Otherness, as signified through the ‘slums,’ festering from within.

Prior to the early 1920s, the domestic space of Others had indeed entered into public debate and concern,11 but it was only in the 1920s that it became a major, if not the, social issue of the time. Aside from Ndabeni – Cape Town’s first spatially segregated housing ‘location’ for Natives – the early years of Imperial Cape Town show a somewhat limited interest in housing and slum conditions, even though cities in England had begun to focus on these problems through the implementation of the Housing and Working Class Act in 1890. Not forgetting the Dutch East India Company’s slave lodge of the 1600s, the Workmen’s Metropole on Prestwich Street, built in 1896 for 200 (Coloured) labourers was the first City Council housing project in Cape Town.12 Apart from this, and a rejected proposal in 1904 for two tenement schemes in Lion and Roeland Streets,13 there is little evidence of public funded housing projects during the Imperial era until the end of the First World War. The projects of the 1920s are generally thought to have their impetus in the country- and world-wide influenza epidemic of 1918 following which a combination of self-interest and philanthropy are thought to have led to public support for slum removals, better housing and the Housing Act of 1920. This support was due to a combination of first-hand experience by middle-class relief workers and journalists visiting the slums in an attempt to investigate and understand the causes of the outbreak.14 Even though the influenza epidemic had the effect of bringing housing and slum questions to a head, prior to this epidemic there had been an increasing official interest, concern and investigation of the living conditions of various communities and places within South Africa and the Cape Peninsula.

This mapping of conditions began in earnest with the Tuberculosis Commission of 1914, which considered the effects and conditions of dwelling space on the spread of the disease. The impetus for, and debates around, the Public Health Act of 1919 and the abandoned Unhealthy Areas Bill c.1920, also illustrate the importance that the Union Government attached to housing conditions prior to the influenza epidemic. In Cape Town itself, in May 1917, an Overcrowding Sub-Committee had been formed out of the standing Special Committee, a year before the influenza epidemic hit the city. As we shall see, this Sub-Committee had been formed almost exclusively to deal with the fairly dense area in Old Cape Town that was known as Wells Square. This Sub-Committee went on to become the Housing and Estates Committee in 1919 and was the main Council organ responsible for the housing programmes of the city.

Apart from the influenza epidemic of 1918, there are other reasons as to why issues of identity concerning housing and slum conditions may have come to a head in the early 1920s. The growing interest in living conditions prior to the influenza epidemic indicates an awareness of the pressure on the existing housing stock due to the increase in population living in Cape Town. This population increase was thought to come from two sources, namely the immigration of Natives to the city following the limiting of tribal land by the Natives Land Act of 1913, as well as an increase in the number of ‘poor whites’ from rural areas due to the effects of drought. By 1922 the increased visible presence of Natives in the space of the city was such a pressing issue the Cape Times stated that ‘there are streets in Cape Town which already resemble Kafir locations of the very worst type.’15 This increase was due to the Ndabeni location – explored in greater detail in the next chapter – reaching its saturation and magistrates refusing to turn Natives out of overcrowded lodgings on account of there being no alternative accommodation for them.16 This period also coincided with the end of the First World War during which little construction had occurred and during which many former dwellings had been converted into stores and offices or demolished for development.17 What houses had been built were largely for the middle class leaving little new infrastructure for immigrants.18 The possible co-habitation of members of different races and the threat to the unity of an emerging White national identity added further complications and impetus to the slum and housing ‘questions.’

The provision of housing – once the dalliance of religious men and philanthropists in England and Scotland – became a state obligation in the UK thanks in part to the Tudor Walters Report of 1917; the First World War had directed the supply of building materials and activities away from speculative housing developments and the lack of housing for demobbed soldiers raised the spectre of Bolshevism as a threat to established social order. In the early part of the twentieth century, the Union Government and the municipality of Cape Town followed the lead of English housing legislation and housing programmes – for example, in the establishment of the Central Housing Board – aimed at dealing with similar housing concerns in the city. And the Spanish ’flu epidemic of 1918, which correlated contagion with spatial density, had the effect of bringing the housing problem to the public at large. It all meant the question of where and how people were to live became a major part of popular and architectural discourse in South Africa at the time.

THE ‘HOME’ AND THE ILLEGITIMACY OF ‘OTHER’ DWELLING TYPES AND BUILDING MATERIALS

During the 1920s, the increasing development of blocks of flats in cities around the country was a noteworthy phenomenon. But more so, it was a cause for alarm, especially evident in the reports prepared by the Architect, Builder & Engineer which were largely generated around social rather than aesthetic concerns. Quite simply, blocks of flats were considered unable to support and cultivate ‘a family life.’19 Exactly why that should be was never explicitly stated and was perhaps thought to be too obvious to need any further explanation or analysis. The lack of a private garden no doubt played a major part in this perception. Perhaps the spatially-compressed transition from public to private realms was recognized in the patterns that flat-dwelling produced and was seen as problematic. Or perhaps flats lacked the litany of rooms fundamental to the activities of homemaking, as we have noted in the previous chapter.

Much more telling was the way in which flat-dwelling was recognized as a direct threat to Englishness itself. The journal noted: ‘In the first place, one of the most disturbing results of the flat-dwelling habit has been to discourage home building, while it also tends to destroy much of that atmosphere of family life which one has been taught to regard as so essentially British.’20 Exactly what phrases such as ‘home building’ and ‘atmosphere of family life’ meant is up for interpretation. They may point to an idea of the quintessential English cottage – a space occupied by individuals involved in quiet activities such as needlework and reading, with the tick-tock of the grandfather clock, and wistful wisps of smoke out of the chimney. Whatever the mental image conjured, what was being implied was that to live in a flat was to assist in the destruction of values that can be considered essentially English21 whereas to live in a single-family detached unit was to continue the essence of being English. To construct the Self as the identity of Englishness, to construct a home required the correct physical backdrop, the correct building type. And the flat was not it.

Another explanation explored in the article was that flats were attractive to members of the middle class who had no family or children and were consequently to be viewed with much suspicion. The Architect, Builder & Engineer saw fit to comment on the increasing claim of flat-seekers that they had ‘no children’ (so as to more easily secure leases) with the following judgement: ‘It does seem extraordinary that in South Africa, a country crying out for settlers of the right type, there should be any tendency or encouragement to check the natural growth of its own middle-class population.’22 The ‘logic’ operating here was that if there were no flats to encourage solo living or couples without children, there would be more English middle-class, child-rich families living in Cape Town. Or the corollary of the statement would be that, were potential flat dwelling and childless members of the middle class to live in single-family detached dwellings, the dwelling type would, perhaps by some necessity of its ‘family-ness’ and garden, give rise to a house brimming with offspring. The article goes on to demand that architects and town planners use all their influence in the development of the city ‘on the right lines for the moral and physical comfort of future generations of citizens.’ Being professionally involved in the development of flats was cast as being involved in something potentially immoral and threatening to the very safety and security of the middle class (read, White and English) in South Africa. And, again, the corollary sentiment would be that to develop and produce freestanding cottages would be to strengthen morality and bolster the dominance of the middle class.

Flats were also, quite simply, considered the very basis for the development of the world’s slums. The Cape Times reported on the 1910 International Town Planning Conference in London that ‘American experts [had] attributed the growth of slums and unhealthiness of many of their cities to the baneful system of flats.’23 As a possible ‘solution’ to the emerging housing problem then, the flat as a typology was unacceptable. As the Durban correspondent of the Architect, Builder & Engineer put it, ‘one of the first principles of a healthy municipality is to house its population well and a community of flat dwellers cannot by any means be considered well housed.’24 Whilst considering flats to have been born out of necessity during a time of limited housing stock, the author went on to predict, somewhat wishfully, that they ‘would die a natural death as time goes on.’

The biggest and possibly most significant condemnation of the development of flats came from the Union Government’s Central Housing Board. As we shall see, it assisted the Municipality of Cape Town in providing funds for the development of a block of flats in District Six in the early 1930s, but considered that to be a special circumstance whilst confirming that ‘generally the Board does not favour flats.’25 To support their position on the matter, the Central Housing Board, which originated out of the 1919 Housing Commission, made the point that ‘The trend in Great Britain is entirely against flats and in favour of separate dwellings and garden plots.’ This deference to the norms and trends of ‘home’ not only illustrates the reality of England as the reference point and source of ideas but that connections were continually being made actively re-inscribing an English identity in South Africa. As a final deference to the authority of the metropole of Empire, the report quotes extensively from Raymond Unwin:

Sir Raymond Unwin, Past President of the Royal Institute of British Architects and an outstanding authority in the world on town planning, states inter alia:-

‘The steady trend of housing progress in this country for forty or fifty years has been towards more open development and less crowding of dwellings. Starting with the pioneer work at Bournville, Port Sunlight, Earswick, Letchworth, and other places, the conviction rapidly spread to all interested in housing that the cottage home with its garden is not only the best form of dwelling for the people generally, but that it is the most economical, and that its general provision is practicable.’

‘Visitors from other countries where the tenement or skyscraper types of housing prevail envy England her cottage habit.’

‘The English people retain their love of individuality for themselves and their family life which springs largely from their cottage homes.’

‘They dislike the “herd” life and the “herd” mind which tenement existence is liable to foster.’

‘No one who has compared life in a tenement block with that in a cottage, with its little garden, in which the children play and where the elders find pleasant occupation and escape from the many occasions for embarrassment and irritation which must arise in cramped domestic life, can for one moment rank life in a flat – however modern in construction and up-to-date in equipment – as comparable to that in the cottage for its value as a dwelling place.’

‘Much may be done undoubtedly to improve the conditions in flats and tenements. The securing of a small open-air balcony as a necessary attachment for every flat would of itself be an enormous boon as would the arrangement of the blocks so that there is, in addition to a place for children to play, some little patch of common garden where people can sit and enjoy a little natural beauty and variety.’26

The report ended with the bald statement that ‘the South African race will not be built up in flats’27 – not forgetting that ‘the South African race’ was the newly represented White race group. This was not to suggest that the single-family detached dwelling was considered to be the sole province of the White ‘nation’ as a way of wresting the recently urbanized poor Whites from the dangerous heterogeneity of the slums; flats, quite simply, were considered abhorrent to any ‘normal’ or ‘decent’ way of living, and this sentiment cut across the emerging racial lines at the time, albeit with differing outcomes.

A report on Herbert Baker’s paper on ‘Town Planning,’ at the Conference on Imperial Health held in London by the Victoria League in 1914, sums up the particularly English sentiment against tenements:

The British people have one fortunate tradition in their favour. This is the principle of the ‘one house one family’ – the cottage instead of the tenement unit – enshrined in their boast that ‘Every Englishman’s house is his castle.’ Fortunately a sound British prejudice has prevented its introduction to any serious extent into the colonies.28

A middle-class prejudice, that is to say. Some 15 years later Cape Town City Councillor, Mrs Horwood, in considering a fledgling scheme for subsidized housing for the poorer classes, requested that the type of dwelling needed to be stipulated in the application as ‘it was not desirable that subsidies should be granted for the erection of tenement buildings.’29 However, two years later, and despite general opposition from other members of the Housing & Estates Committee, she came out in support of a tenement scheme for the city centre30 – albeit on the condition that municipal housing schemes in general needed to be managed and controlled on site by a council employee. This emerging ambivalence over the need to accommodate flats as a typology can also be noted in the communications of the Citizens’ Housing League (hereafter CHL). Perhaps realizing the real insistence of the inner-city poor for dwellings near their place of employment, the Housing Committee received a letter in July 1927 from Bishop Lavis requesting the chance to secure a site from the municipality on which to conduct an experiment involving a two or a three storey tenement containing ten flats or houses. A little more than two months later the CHL reported to the Housing Committee that they were ‘strongly opposed to any form of tenement building.’31 The reasons given were that there was an ‘instinctive dislike … universal among the poor’ as well as the notion that ‘privacy, individuality and home feeling cannot be obtained except in a separate house.’ The intention to impart values of Englishness through housing cannot be more clearly spelt out.

The spatiality involved here needs to be made explicit. With the physically separate house comes the mediation of a separating space that produces in its isolation the possibilities of privacy and individuality. The gate and the garden fence are the real threshold of the house. The tenement, on the other hand, with its stairwells and its spatial proximity of units, was more likely to produce an immediacy of contact, working class solidarity, and communal interaction. As a White national identity was being wrested from the bulk of local history, the possibility of tenements to increase miscegenation and interracial interaction would potentially undermine a unified White ‘nation.’ Even as sentiment began to change regarding the need for tenements, the single-family detached dwelling still won out on account of its segregationist possibility. At a meeting to consider the Central Housing Board’s proposal for subsidized housing, the Mayor was minuted as being

not in favour of the erection of tenement buildings as conditions in Capetown could not be compared with those overseas where there was not a mixed population to contend with. He suggested that for the present no proposals in this direction should be considered at all.32

In this sentiment he was not alone. At the conclusion of Housing Week in 1929, the Cape Times asked the question: ‘Are the slums going to be replaced by model dwellings?’33 Notwithstanding the fact that it reported the successes of higher density housing developments in Europe it suggested that the Garden City approach was ‘more suitable for our population of mixed races and colours.’ Although no explanation was given, it can be assumed that the possibilities of ‘contact’ would be greatly reduced in the isolationist space of the Garden City. The tenement, on the other hand, presented, through its compression of space and closer adjacencies of neighbours, the potential for chance interaction across colour lines and the possible forging of a non-racial working class.

The density and communality that tenements or flats were thought to foster was particularly worrying for the agents of Empire and generally thought to foster slums. Even single storey row-houses or terraces were considered problematic. Although there had been an unbuilt proposal for terraces for the working classes by the Council in 1905, this kind of accommodation had long been considered problematic as a housing type for the working classes by a variety of people. This is borne out in the Presidential address of the CIoA in 1907, wherein Parker urged architects to get more involved with the design of working class houses.

If one were asked what is the worst kind of building we have in the city to-day? I think the answer would be ‘The dwellings of the labouring and working classes.’ This class of building has never received proper attention in this town, and the demand for houses of this kind, during the recent time of prosperity, created whole rows and streets of them, very little better than the old style of houses.34

Before leaving this section on the flat, the tenement, and the terrace as the ‘wrong’ model for the Self, note that the antipathy toward any dwelling that was not in some general sense a replica of the English cottage and its low density extended to the use of building materials and construction techniques in general. Again, that Cape journal of architectural Englishness, the Architect, Builder & Engineer, flew the flag of Empire in an article on Chinese houses. Here George Cecil found it curious that the Chinese had not ‘been taught a lesson’35 and taken up European designs and methods given the immediate availability of the European examples in Hong Kong and elsewhere: ‘The houses in the treaty settlements show the latest in Western architecture; those which form the adjoining native quarter might have been built six hundred years ago.’36

This antipathy to strange building types and construction techniques was especially true of those materials considered to be ‘temporary’ – notwithstanding the aesthetic crime perpetrated by corrugated iron users. Another excerpt from an article in the Architect, Builder & Engineer – un-ambivalently titled ‘Freak Houses’ – is a good illustration of this:

Recently there has been some discussion in the Press, both overseas and here, of cheaper methods in building houses, and someone has put forward the suggestion of adopting a Japanese idea of erecting paper houses; to make them more or less weather-proof they would have to be oiled. This scheme seems to have a certain amount of popular fancy, and the result is there are all sorts of amateurs bringing forward suggestions for cheap houses, varying from brick to pise and in the intermediate stages are glass, wood, iron, tin, asbestos, oiled silk, etc., almost varying from the present state to the snow hut of the Eskimos. There is no getting away from the fact that wherever one may go there are oddly built houses, but they do not conform to any idea of stability. Whilst they may meet a present need or a hollow pocket they are not buildings in the true sense of the word, even though they may conform to an architectural setting as far as the surrounding background is concerned. To any one who has visited Bakoven, Clifton, and Melkbosch Strand and one or two other seaside resorts, it is really appalling to see the weird erections and they are likely to last for some time before they are pulled down. All credit may be given to the owner for doing the best he can on a limited purse, purely from an artistic and serviceable view-point, but the fact remains that many of these buildings are solely temporary, and may therefore be classed as freak houses.37

The quote illuminates some of the values associated with Englishness and architecture. For example, the title ‘Freak Houses’ and the notion that they were held in ‘popular fancy’ echoes the suggestion that there was a certain fascination with these Other building materials. Yet it also hints at a kind of repulsion at their deformities, the reflection of the Home disfigured – in line with the fascination Englishness held for the deformities of London’s ‘Elephant Man’ and other East End horrors. The hierarchical arrangement of building materials, from the most ‘stable’ brick to the most ‘unstable’ mud, is particularly interesting given the general association of mud with Native dwellings – indigenous building techniques were obviously not valid answers to the housing question. The phrase ‘buildings in the true sense of the word’ is perhaps key in the above quote because it captures the polarity of legitimacy and illegitimacy that operated within the value judgements made of all dwellings. This was not to say that the idea of experimenting with new or old technologies was not actively considered, as it was in the housing programmes underway in England.38 Indeed, the Central Housing Board occasionally made overtures to that effect, yet always condemned materials other than ‘solid’ brick, and occasionally, allowing concrete into the mix.

COMPETITIONS, EXHIBITIONS, MODELS AND PUBLIC EVENTS

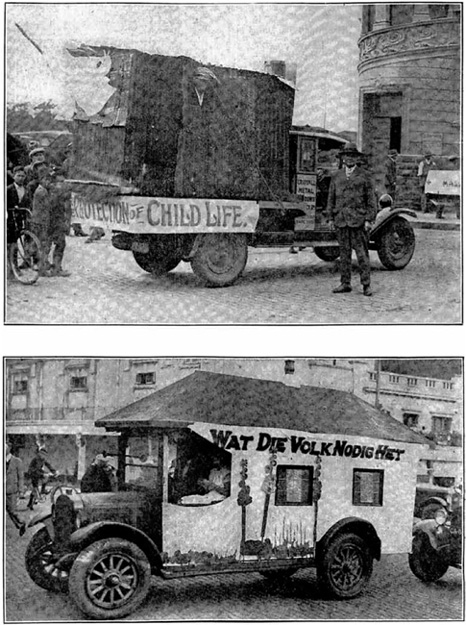

On Saturday 12 August 1929, a lorry and a motorcar were driven through the streets of Cape Town (Figure 6.1). The lorry, carrying a ‘dilapidated tin hut’39 culled from the wilds of the Cape flats, was a point of ridicule and shame. The motorcar, on the other hand, was re-crafted into a kind of twee cottage-on-wheels with the Afrikaans phrase ‘Wat Die Volk Nodig Het’ (what the people need) painted on the side. Despite the choice of language, the spectacle was all about staging Englishness. The Cape Times ran a caption interpreting the Afrikaans phrase as ‘What Many Need – A Model Cottage’ – a conviction much stronger than the flimsy board the model of the ‘model’ was made of; the ‘flimsy’ corrugated iron shack was ironically more solid and real than the ‘brick’ cottage draped over the sides of the car. Both were part of a parade, part of the ‘Housing Week’, organized by the City Council who had turned the interior of the City Hall into a spectacle of horror and hope. Charities and other interested organizations decked the interior of the City Hall with depictions of slum dwellings painted on canvasses. Films of slums and slum life ran constantly. Although the City’s Public Health and Building Regulations Committee (PH&BRC) had been promoting Health Weeks during the 1920s (keeping in line with themes generated in London),40 this was the first event focused specifically on slums and housing. The Housing Week, given much credence at the official opening ceremony by the attendance of Princess Alice and Dr Malan – the Minister of the Interior and Education and apartheid South Africa’s first Prime Minister in 1948 – pointed to the perceived seriousness of the housing problem in ruling circles. Yet again, the cottage as ‘model’ was the star of the show.

6.1 Cape Town Housing Week parade – from shacks to model cottages

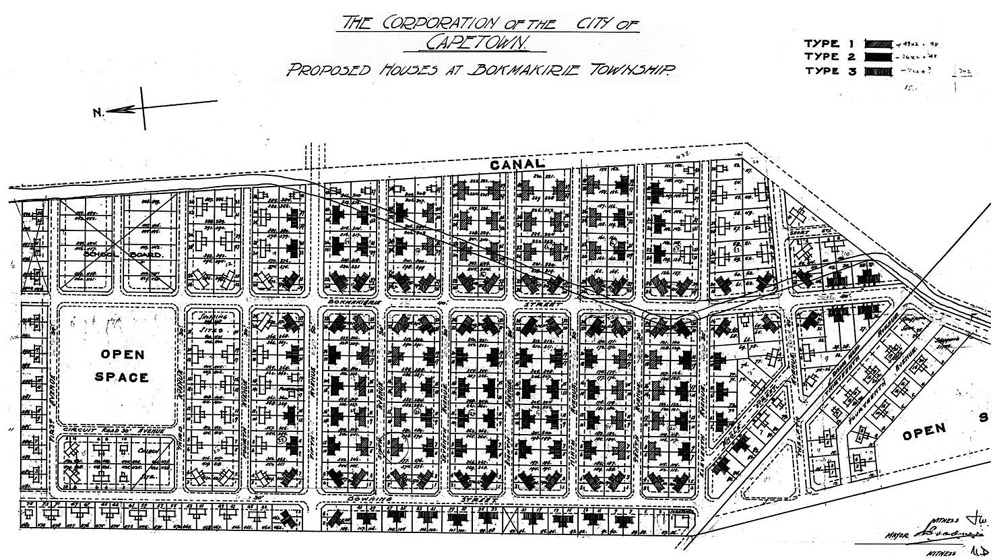

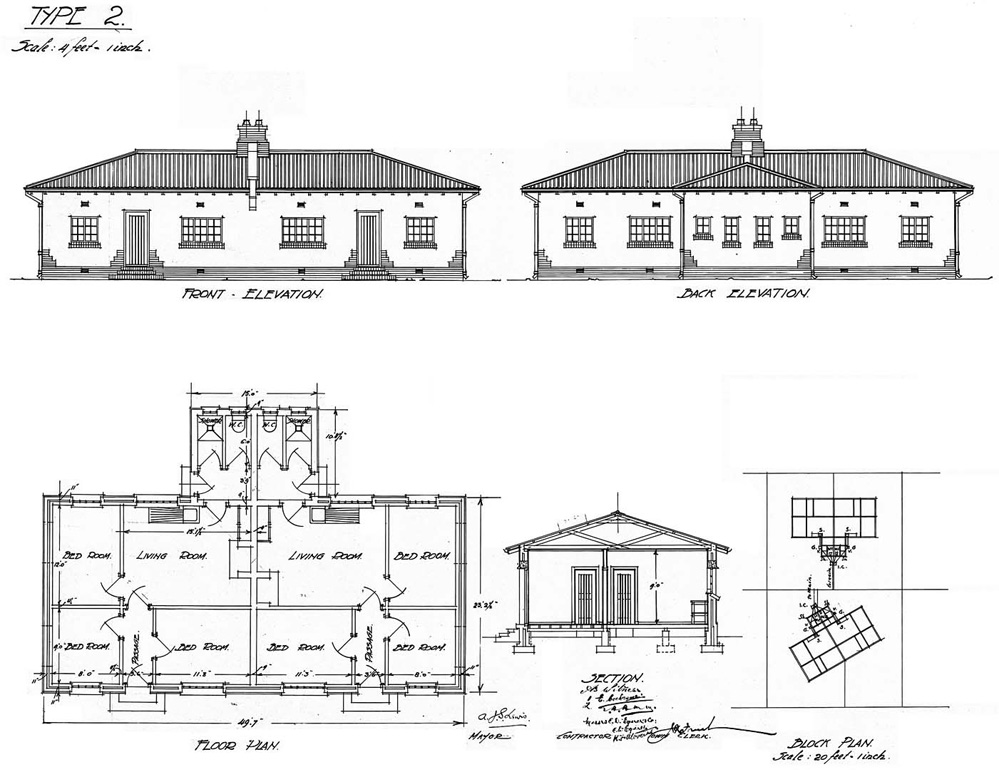

6.2 Central Housing Board, Report dated 31 December 1920, plan Type 1, three-roomed semi

In as much as the ‘model cottage’ floated around the streets of Cape Town in parades, it also haunted other representations and contexts such as the Central Housing Boards’ first annual report of 1920. Here, as Annexure C of the report, was a set of model plans for adequate house types prioritized for funding (Figure 6.2). They were not exactly blueprints for municipalities as much as models against which municipal engineers and architects might evaluate their own designs before applying to the Central Housing Board for financial assistance.

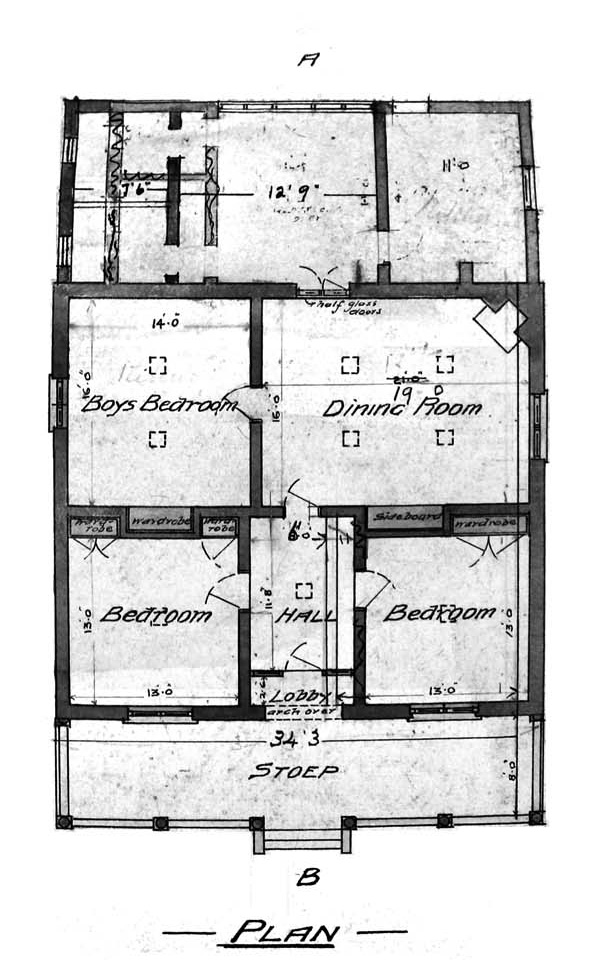

These were sent to all municipalities in South Africa in a memorandum.41 The plans were all semidetached dwellings – a minor compromise by the Board over the cottage as the ‘correct’ way of living – specifically restricted to single-family units with a minimum of three rooms. The labelling of the plans scrupulously prescribes activities and functions as an antidote to the motley undifferentiated character the official gaze ascribed to the domestic space of Others.

But it was in competitions for ‘ideal’ or ‘model’ homes, often sponsored by newspapers and journals, that the ‘model cottage’ was established as the ‘correct’ manner in which to live. Newspapers even sponsored garden competitions.42 The winning entries are all single-family detached units and the designs tend to be focused on achieving this ideal without undue financial and cultural compromise.

One of the earliest was the Cape Argus ‘Model House’ design competition of late 1922 and published in early 1923. The cost of each house was roughly £1,100 and way beyond the means of most of the urban poor. The ‘model house’ had three rooms, excluding the kitchen and a servant’s room, located on a standard suburban 50’ × 100’ plot. The results were typical of a ‘cottage’ in Arts and Crafts parlance. What is apparent from the designs, especially the second place winner, J. Lockwood Hall, was that the need for a hall was unquestionable no matter the ‘class’ of dweller or cost of the dwelling, given the presence of a live-in servant or maid (Figure 6.3).43 In South Africa’s White suburbia, this spatial segregation increased as the living quarters for the maid or servant moved over the years from inside the house to the back yard, typically as part of the garage.

6.3 The Cape Argus Model House competition, second place winner, J. Lockwood Hall.

The unplaced but published entry of Martin Adams, a student at the recently established school of architecture at the University of Cape Town, was a design with a ‘cosy fireplace’ (as labelled on his plan) – a clear reference to one of the essentials of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Promotion of ‘ideal’ or ‘model’ homes by newspapers and magazines was not limited to competitions. The Cape Argus newspaper ran an article titled ‘A £1,250 House: What Can be Done,’ signed ‘By a S. African Architect’. The article urged ‘small houses’ – ‘cottages’ and ‘bungalows’ – to be provided at a low cost, and, in the spirit of the Arts and Crafts, demanded that these eliminate the ‘superfluous and fanciful and to make use and clear expression of local materials and conditions.’ As a showcase of what was possible, given a limited budget and the minimum accommodation required, the article presented Walgate and Ellsworth’s design for G.A. van Oordt’s ‘cottage’ for Pinelands Garden City. The author commended the architects on their sympathetic use of ‘traditional local materials – thatch and plaster.’ Central to Arts and Crafts sentiment was that houses be simple, largely undecorated and, as they said, ‘not contorted to satisfy any false idea of the beautiful.’

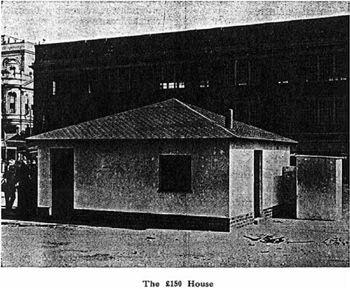

In 1927, the Master Builders’ Association, seeking to promote their view of what low-cost housing should be, suggested a design that was simple in the extreme, lacking any Arts and Crafts sentiment and was reputed to cost £150. This ‘cottage’ was eventually built on the Parade, Cape Town’s largest public square, and consequently became known as the Parade Cottage or Parade House (Figure 6.4).44 Such a prestigious location highlights a deepening awareness of the housing question. It captured the public imagination and the Council, which had originally authorized the Cape Peninsula Building and Allied Trades Association to build the Parade Cottage on 28 July 1927 for a three-month period, happily extended this.45 When the Citizens’ Housing League proposed to take over the running and maintenance of the exhibition cottage in order to keep the model present in the public eye, the Housing Committee was granted permission46 by the City Council to provide them with a £6 monthly maintenance. The Parade Cottage became such a reference point that the Housing Committee, considering the Oude Molen and Devil’s Peak housing schemes, referred to the proposed houses as ‘Parade Cottages.’47

Not everyone supported the design of the cottage. The editor of the Architect, Builder & Engineer, whilst considering it better than the ‘wretched tenements in which our poorer citizens, both white and coloured, at present have their being,’ felt that it would be a ‘tragedy from the public expenditure and from the public interest point of view’ if hundreds were to be built.48 Though their objections related to poor planning in the use of space and concerns over the privacy of the inhabitants, and that the dwelling did not conform to building regulations, there is a sense that the complete lack of Arts and Crafts motifs was what Delbridge found most problematic. The publication consequently promoted a counter-competition for low-cost houses (as will be discussed below), in which Arts and Crafts detailing was made more manifest.

6.4 ‘The Parade House’ on display on Cape Town’s Grand Parade

The ability of ‘art’ to ‘uplift’ the poorer sectors of the community,49 a link that the Arts and Crafts movement manifested in building design, was being promoted. At a meeting of the South African Guild of Arts and Crafts, at which W.J. Delbridge, handed over presidency to the architect Frank Kendall, the Secretary Arthur Cook championed the edifying benefits of art and urged all present to ‘hold themselves responsible for seeing that the children who were being born into such conditions [of the world today] were supplied with the right surroundings and influence, for these would materially alter their characters and their whole lives.’50 The Architect, Builder & Engineer’s ethical scorn for the Parade Cottage was most likely based on the loss of that ‘uplifting’ effect a more picturesque cottage would apparently have had on its occupants.

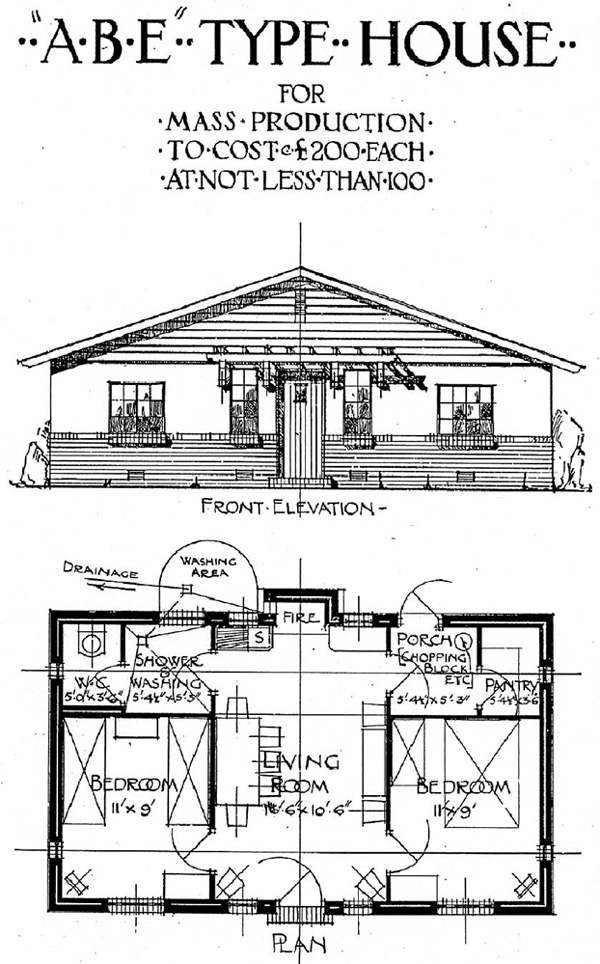

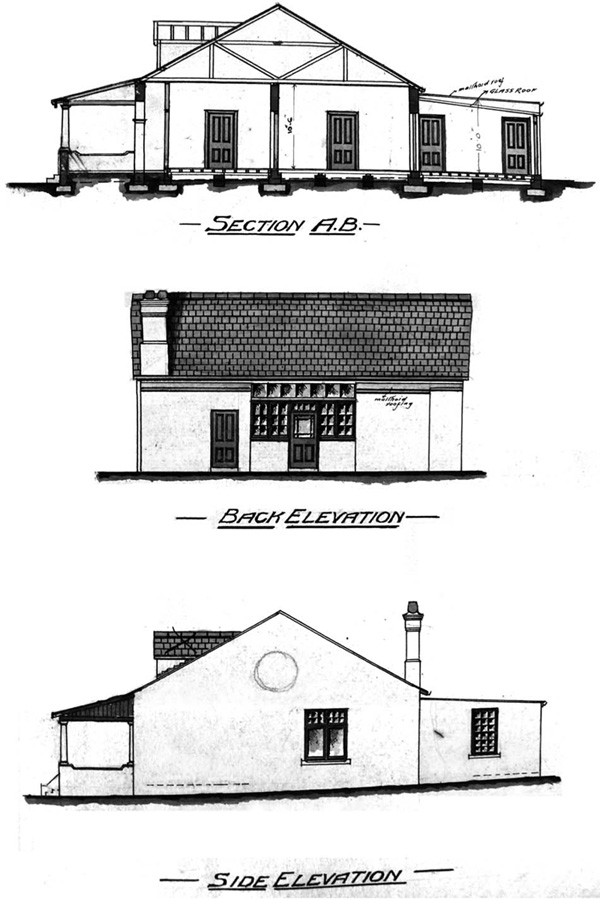

Later that year, the Architect, Builder & Engineer ran a competition for housing for the ‘poorer classes,’ which, if 100 were constructed, the cost of each needed to be below £200, excluding the stove and drainage.51 The editor was aware of the need for three bedrooms in order to ‘house in decency and comfort the parents and the children of both sexes,’ but felt that the house was initially to have only two bedrooms and then be added to later. As part of the publication of the winning designs, Delbridge included the Architect, Builder & Engineer’s ‘entry’ (Figure 6.5). With a strong sense of functional detailing, he noted that ‘the narrow sides of the building do not contain any openings that could be overlooked and the privacy of the interior of the building thus destroyed,’ and further, that the ‘bedrooms are sufficiently far apart to ensure privacy.’ The most striking aspect of this ‘entry’ is its Arts and Crafts character, though this is manifested through the external appearance of the cottage alone – the lack of telltale ‘nooks’ or a ‘cosy’ on the plan suggests that expense-related Arts and Crafts concerns were jettisoned in favour of superficial image effects.

6.5 The ‘entry’ of the AB&E to its own housing competition

The urban design aspects of the imagined housing scheme and ways of introducing variety in the appearance of the designs, such as the cul-de-sac of the Architect, Builder & Engineer house, remain telling. The ability for the first prize entry, designed by the architectural lecturer at the University of Cape Town, J.H. Brownlee, to produce variety in the landscape thanks to its ‘L’ plan form, was also noted as was the negative aspect being the use of corrugated iron for the roof so as to reduce the overall cost of the project (Figure 6.6). Although the plan could easily accommodate a semi-detached layout, this possibility was not commented on by Delbridge, nor was it considered in the overall project design; clearly the single-family detached unit was the only legitimate dwelling under consideration and aside from the Arts and Crafts detailing – the acme of Englishness – what the Architect, Builder & Engineer essentially presented as the housing model for the ‘poorer classes’ was a de facto suburb.

6.6 Winner of the AB&E housing competition, J.H. Brownlee

DENSITY: MUNICIPAL STRUCTURING OF CLASS AND THE VILLA AND COTTAGE AS IDEAL

Aside from these limited ideological forays, the battle to remake Cape Town into a suburb of cottages and villas and the instrumental effect this would have on the structure of society as a whole was more fully dramatized in the administrative and legislative acts of the municipality. More to the point, the hierarchy of class evident in English society at the time was directly correlated with a hierarchy of building density – the more free-standing a dwelling the more it tended towards the ‘better class.’

In other words, zoning housing density was a useful official tool in the de facto protection of class interests while the zoning of class districts structured Cape Town itself. The relationship between class and building density was explicit in the building regulations of 1920. The CIoA, and in particular Frank Kendall, had given extensive input into their drafting, with 25 of their 28 suggested amendments included.52 Regulation 807 restricted the subdivision of estates to 4 to the gross acre for ‘important residential districts,’ 6 for ‘ordinary residential districts,’ 8 to 12 for ‘mixed districts’ and 12 for ‘shopping and industrial districts.’ Regulation 808 restricted the coverage of the site by built footprint: no more than one-quarter of the site was to be built upon in ‘important residential districts,’ one-third for ‘ordinary residential districts,’ and the rest were restricted to no more than one half. Exactly what determined the class of a residential district as ‘ordinary’ or ‘important’ was not laid out in the regulations and the City Engineer was most likely to take cues from already subdivided adjacent estates.

Dismissing any doubt as to the underlying intentions of these density regulations to structure the class of a neighbourhood through restricting the type of building and the density of the neighbourhood, regulation 809 gave the Council the power to prohibit new buildings of a ‘character detrimental to the rest of the buildings on a subdivided estate’ while prohibiting ‘any building intended for use as shops, cottage property in terraces, licensed premises, places of amusement or buildings of the factory class in such districts as may be deemed expedient.’ Not only was class being structured through density regulations, it was inferred through building typologies and the nebulously defined ‘character’ of a building.

Terrace houses associated with the poor and working classes were unceremoniously lumped together with other potential ‘nuisances’ of the city such as pubs and factories.

As exemplified in the application for plans for terrace housing submitted by Mr A.J.F.B. Erustzen in Worcester Road, Walmer Estate, prior to the revised building regulations of 1920, the municipality could not control the extent of property subdivision and development or the ‘degeneration’ of a neighbourhood through densification. The PH&BRC regretted approving the application given that there were ‘some detached villas of a higher value’ in the vicinity and the project would prove ‘prejudicial to the property in the immediate neighbourhood.’53 They resolved to coax the applicant into substituting a ‘better class’ of dwellings than those proposed. With regulation 809 they now had the power to categorically refuse such developments and bring a class-based structure to the city.

Plans submitted by J.E.C. Killey and Co. for six dwellings at a property off Avenue de Longueville, Sea Point, illustrates the values and machinations involved in the de-densifying of Cape Town. Although the application was initially refused due to the density set at six dwellings to a third of an acre, permission was granted when it was pointed out that there was nothing in the regulations preventing the owner from developing a block of flats on the site because ‘the Sub-Committee were of opinion it was preferable to have six small detached houses instead of a block of flats.’54 Approval was eventually rescinded following a site visit where it was agreed that the area should be classified as an ‘important residential district,’ which would put the maximum density at four to the acre.55

Low-density restrictions were also intended to have an impact on the city centre itself. When Mr C. Paitaki submitted plans for a development of about 20 properties to the acre near Milner Road and Buitengracht Street, the City Engineer pointed out that as an ‘ordinary’ residential district the maximum allowed would be 6 to the acre, whereupon the PH&BRC did not approve the plans.56 The problem facing the City Engineer was areas of the city that had been subdivided to a density greater than 12 to the acre before the 1920 regulations.57 In a meeting set up to deal with this, the Townships Board was resolute that ‘a density exceeding 12 houses to the acre will only create slums,’ and insisted that the regulations be revised to prohibit this occurring.58 When it was pointed out by J.Z. Drake of the PH&BRC that the lower densities disallowed the poorer classes affordable rents A.H. Cornish-Bowden, Surveyor General and Chairman of the Townships Board, retorted that with frontages as low as 16 feet ‘there was the aesthetical point of view to be considered, there was no provision in these small houses for a garden in front.’59 The issue was partially resolved by the Township Board requiring the approval of a subdivided estate before any plans could be submitted ensuring thereby that ‘correct’ densities were determined by minimum plot size rather than building plan approval.60

Restrictions on density were not only intended to structure class through the environment – whilst securing public health – but also to socialize families into middle-class values. The maximum density of 12 plots to the acre came close to, but did not necessarily add up to, a street of terrace houses and was generally the maximum density expounded by Garden City promoters such as Raymond Unwin. Furthermore, ample space was allowed for front and rear gardens – a key technology of Englishness. This was an ordering principle well-known to the Surveyor-General and Chairman of the Townships Board. In an article in the Architect, Builder & Engineer, he warned that developers wanted building regulations to allow 17 to the acre disallowing the ‘humanising influence which a small garden provides’ and forcing children to ‘adopt the streets as their playground.’61 He balked at the suggestion that housing schemes within the City proper should be permitted densities of 17 dwellings to the acre as they would ‘inevitably become slum properties in a few years.’62

The building regulations of 1920 were explicitly aimed at preventing the kind of dense social environment that characterized neighbourhoods such as District Six from developing. Technical specifications like street widths and the location of building lines were driven by concerns for maximizing light and air for dwelling spaces. In contrast to parts of District Six where buildings were often built at the property line, regulation 811 required a set-back of ‘not less than fifteen feet or not more than twenty-five feet in the case of main streets; and not less than ten feet or not more than twenty feet in the case of secondary streets,’ effectively instituting a front garden space. Regulation 814 defined a minimum street width by setting the distance between opposite property lines beyond 24 feet. Perhaps as an acknowledgement of the slum clearances that were to follow, regulation 816 even required new buildings to ignore existing building lines set down in the physical form of the street and set buildings back a minimum of 12 feet from the centre of the street for those streets less than 24 feet in width. Any existing alley was to be reorderd into the width of a minimum street as each new building project was developed with an eye to possible future slum clearances. Acknowledging the work undertaken to reorder Old Cape Town, regulation 818 explicitly allowed the Council to instruct owners to remove existing stoeps or other projections beyond the property line.

With the building regulations of 1920 the City managed to develop a generalized system of structuring class while inculcating English suburban values across the entire corpus of the city. It was with their ad hoc Assisted Housing Schemes that they started to sketch in the details of this class-based structure of the city.

HOUSING LEGISLATION AND THE ASSISTED HOUSING SCHEMES

After the First World War, the Cape Town municipality was involved in the administration and provision of individual houses through state- and provincial-funded schemes. These are the focus of this section. Thus two legislative events helped structure the domestic space and thence the identity of the Cape Peninsula, both of which were ostensibly crystallized as a result of the influenza epidemic of 1918.

The Municipal Provision of Homes Ordinance of 191963 allowed municipalities to forward money to the working poor to purchase and build approved dwellings within the municipality. The loans were payable at 5 per cent interest per month provided the applicant could make an initial cash payment of 20 per cent of the projected land and building costs. The loans were restricted to families represented by ‘deserving’ male applicants who earned less than £360 per annum and who gained no less than four fifths of their income through ‘actual personal exertion.’ That the single-family detached unit was the imagined and only legitimate form of dwelling eligible for funding of this type is suggested in the definition given to ‘dwelling house:’

‘Dwelling House’ includes the house and its appurtenances, necessary out-buildings, fences, and permanent provision for lighting, water-supply, drainage and sewerage, but does not include the land. ‘Family’ includes the parents or other relatives dependent on the applicant or borrower.

The ambition of the Ordinance was to help worthy working men ‘erect a dwelling-house as a home for himself and his family, or, after erection or partial erection of a dwelling-house, to enlarge or complete the same’ [emphasis added]. Although the possibility existed for non-nuclear or extended-families to be included in the scheme, these had to be headed by a gainfully employed male. Inherent in the structure of the scheme – it being practically impossible to join-up with a neighbour and build a semi-detached dwelling – was the detached dwelling on its own separate plot.

The Housing Act of 192064 was very similar to the Ordinance, but with countrywide reach. In this case the State would provide funds to local authorities for housing schemes that had been approved by the provincial administrator at the recommendation of the Central Housing Board. Although the Central Housing Board did not plan the housing schemes, it was specifically established by the Act to provide assistance and guidance to local authorities on the appropriateness of the schemes, even providing model plan types as we have seen earlier. It was only in 1933 that the interest rate on the Central Housing Board recommended loans was dropped to below prime – ‘sub-economic’ as it was called – effectively allowing subsidized housing for the poorer classes, especially for Natives. Until that point, the Provision of Homes Ordinance and the Housing Act were essentially only effective in providing houses – at the poorest end of the scale – for artisans who could keep up payments on the loan. Indeed, a certain amount of screening was implemented so as to prevent the municipality from losing money on the loans it made to those applying for assistance under the Act and Ordinance. These two policies were effective in, and possibly intended to, secure the position of the poor urban White population and achieve racial residential segregation.65 It is worth taking a closer look to see how the implementation of these individual house schemes (as opposed to housing projects) may have had a basis in the desire to structure the domestic space and identity of different class and racial groups in Cape Town.

It is important to clarify the various mechanisms through which the City Council, through the Housing Committee, built these individual houses. Both the Ordinance and the Act allowed individuals to apply for loans made available through the Council, although the Act required funds to be provided through central government. In both cases the Housing Committee was burdened with the task of approving each individual design as it was submitted to them. The schemes were marked in their initial stages by a slow take-up; only two applications totalling £1,800 were submitted and approved by the Central Housing Board in 1923 out of an available amount for that year of £18,500.66 By May 1927 the two schemes were fairly effective in helping increase the working class or artisan’s housing stock: 321 homes were built through the Ordinance system and 163 through the Housing Act, dotted around the suburbs of Cape Town.67 The three-bedroom dwelling with its wooden floors and tiled roof at Belvedere Road in Claremont is a typical ‘cottage’ funded under the Provision of Homes Ordinance (Figure 6.7).

There is no reason to believe that funds were denied on account of the race of the applicant and the intended neighbourhood for the development of the dwelling. As we have seen this was a class issue, structured by building regulations related to density and ‘class’ of dwelling and the appropriateness of the cottage to the existing neighbourhood. The schemes were clearly efforts aimed at ‘saving’ worthy families from degeneration, the latter happening due to their close association with degenerate types in the denser parts of Old Cape Town.

Different conclusions can be made of the Municipality’s Assisted Housing Scheme in wood-and-iron that developed a few years after the Ordinance and the Act but which then ran concurrently with them. This scheme aimed to re-house those in the suburbs who were living in self-built and unlicensed dwellings. As we will see, the Assisted Housing Scheme was race and area specific in its allocation of funds. The scheme was first mooted in 1922 when two members of the PH&BRC reported on the increase in informal settlements in the Cape Flats areas and in particular Meadows Estate in Claremont. The report suggested that the mostly Coloured occupants had been turned out of the more populous areas of the city and had bought plots on the Estate in the belief that they could erect whatever dwelling they saw fit on the land. The following is an extract from Henshilwood and Somerville’s report:

6.7 Cottage for Mr R. Delvin, 1922 under the Municipal Provision of Homes Ordinance

C. is a Municipal employee – Sanitary Cart. Has three plots purchased at same rates. Has a small hut of tin and wattle on each plot. Himself and two brothers and their families live in these huts. The huts are tumble down, dirty, and quite unfit for decent dwelling … It is easy to serve notices upon these people and to tell them they must either build proper houses – as approved by the Council or clear out. It is by no means certain that they can, or will, do either. They are their own architects and their own builders, and their ideas of house planning and house construction are not such as are likely to receive approval of our officials.68

For these City Councillors turning these occupants out of their dwellings ‘would be the essence of Municipal inhumanity,’ and suggested a scheme that eventually solidified as the Assisted Housing Scheme. Although they initially considered pise-de-terre, the scheme was limited to wood-and-iron, and then later, brick. Applicants could choose from three standard designs ranging from one living and one bedroom to one living and three bedrooms depending on their income. The Council would erect the ‘cottages,’ as they were called, on land owned by the applicant or selected by the Council so as to replace the ‘hovels’ that were being lived in. In 1922, £10,000 was voted to clear the Meadows Estate of the unauthorised dwellings.69 Applicants had to pay an initial £10 down-payment and then pay the Council a monthly rent on a hire purchase scheme. This gave the Council the opportunity to police and control the social space of those who lived, literally, at the margins of the city. In fact, this was included in the hire purchase agreement which required – as a notice advertising the scheme suggested – ‘keeping the place clean and tidy, and keeping the house in repair at the expense of the applicant, and about good behaviour,’ on pain of eviction and expulsion.70 The notice also made it clear that ‘the man the Council wishes to help is the decent man in regular work, and only such men will be accepted.’ Three testimonials were required as part of the application.

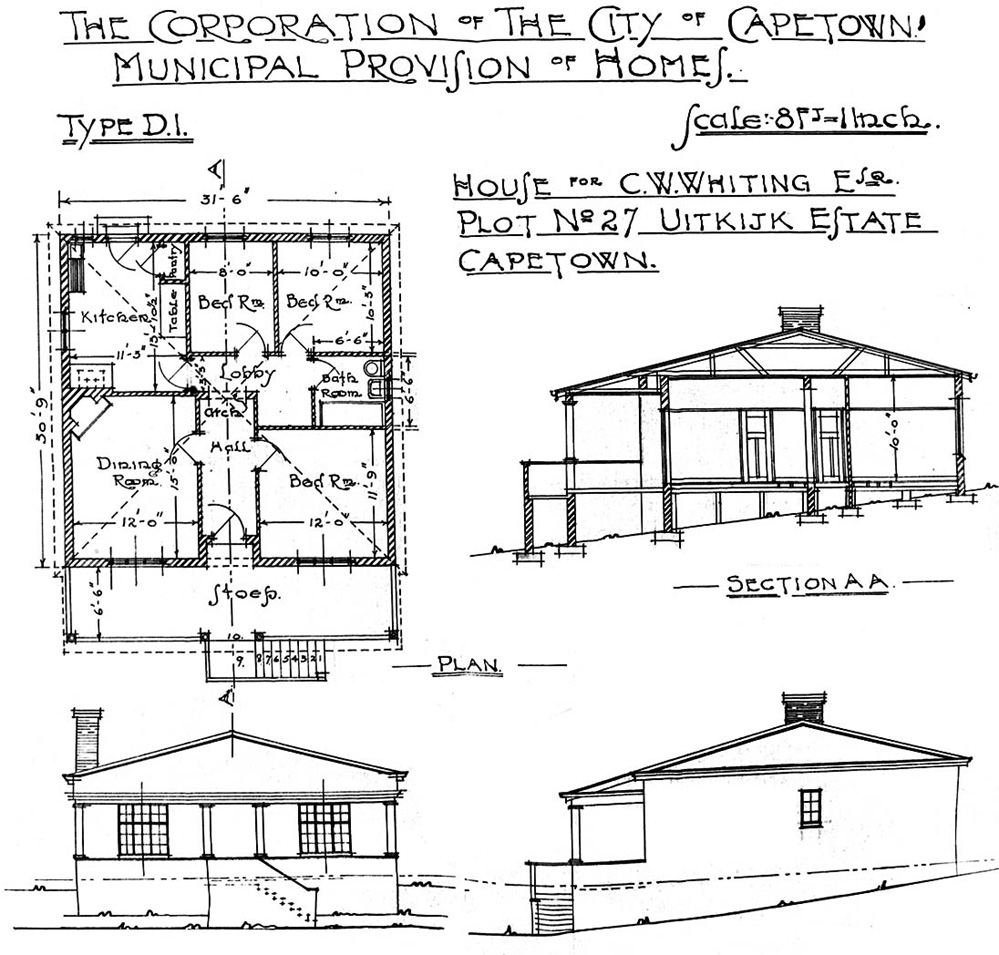

6.8 Assisted Housing in brick, 1924, Type D1 (left) and standard wood-and-iron with additional room, 1930 (right)

A few examples of the applications show the inadequacy of the scheme in dealing with the reality of extended families and their mismatch to the model plans being developed. Another sticking point was the fact that women were possibly driving the applications through their status as the breadwinner. M.J. Arendse came before the Housing Committee on behalf of his wife for assistance to enlarge and complete her house in Rylands Estate on the Cape Flats. This was to allow her mother to live with them, and that the extra two rooms and the kitchen were for her use. The Chairman, W.C. Gardener, ‘felt sure the Council would not advance money for the building of two houses,’71 presumably to ensure that no sub-letting would take place leading to ‘overcrowding’ and social degeneration. In another recorded case, Mr F.G. Van Tura required a house with three rooms and a kitchen due to the fact that his sister, her husband and their three children were living with him. 72 The Assisted Housing models with their restrictions to one dwelling per plot and the ‘moral’ strictures of sex separation in the building regulations, rendered extended families such as these as abnormal and improper.

The Assisted Housing Scheme was implemented to achieve some kind of simulated ‘normality’ in the marginal spaces of the city. That the Housing Committee was keen on implementing ‘proper’ houses and not simply warding off potential disease through unsanitary conditions is borne out through closer examination. Until 1924, the Housing Committee had been funding schemes for occupants of dwellings that were not particularly unsanitary and were funded either on the basis of their ‘unsightliness’ or not being ‘proper’ dwellings. In February 1924, the Sub-Committee of the Housing Committee dealing with the Assisted Housing Scheme noted the need to give priority to those people living in unsanitary conditions – assuming they had met more than 75 per cent of the payment for the land on which they lived. This suggests – up until 1924 at any rate – that it was individuals and their families closer to the middle-class values of the agents of Empire who were the main focus of this scheme. Further, the whole of the Athlone area in which wood-and-iron dwellings were largely permitted and in which houses had been developed on an ad hoc basis through the various single-house schemes, was never laid with any sewerage or other services. Yet in 1927 Councillor W. James in an interview with D.F. Malan, the Minister of the Interior and Public Health, called Athlone a ‘model village.’73 It was on the whole touted as a major success – until the area flooded in heavy rains in 1929. The point is that slop collections and septic tanks were de rigueur at Athlone much as they were in many of the informal settlement areas; its success lay in its provision of ‘proper’ houses as manifested through single-family detached units and not necessarily on the provision of sanitary infrastructure.

Nearly two years after the Assisted Housing Scheme had been mooted, the City Engineer and Councillor W. James who was himself a builder, drew up plans for model brick houses to be delivered on the same lines as the wood-and-iron dwellings.74 Eventually a wide range of model plans were developed (see, as an example, Figure 6.8). Councillor James also promoted the development of an area of Athlone called Milner with many wood-and-iron dwellings being built,75 with a rider added within the very details of the dwellings themselves. They had been designed in such a way such that the roof eaves over-sailed the walls thereby allowing the corrugated iron to eventually be taken off and replaced by a brick layer.76 Although the wood-and-iron dwellings were restricted to areas set aside for their development, James’s brick houses were also permitted within these areas. Eventually, however the Milner scheme restricted the development of brick dwellings to plots 191 to 196 and the wood-and-iron to plots 5 to 10.77

The Assisted Housing Schemes, contrary to their general ad hoc nature of implementation, veered close to outright racial segregation when a major development planned for the area on the ‘opposite side of Klipfontein Road at Athlone’ was intended for ‘Europeans.’78 This scheme was not developed. The structuring of class through space was further implemented when the Claremont Ratepayers Association complained that the Assisted Housing Scheme’s proposed brick houses for Livingstone Road in Claremont were on plots ‘too small and not suitable for a suburban district, and [asked] that a more suitable plan be devised.’79

By May 1927, 87 wood-and-iron dwellings and 201 brick dwellings had been built under the Assisted Housing Schemes.80 Separate figures were given for Athlone with 146 wood-and-iron dwellings and 115 concrete dwellings built, presumably under the same scheme.81 The PH&BRC eventually decided to restrict, in general, the building of wood-and-iron houses limited to the west through the Cape Flats railway line and bounded by Klipfontein Road in the north and Wetton Road in the South.82 There was, however, no boundary to the east; the space of the Other could extend into the wilderness.

WELLS SQUARE SLUM CLEARANCE AND THE CITY’S FIRST GARDEN SUBURB HOUSING PROJECTS

The New Year’s festivities of 1915 saw the City of Cape Town wake up to a rather large hangover. In the first week of January, the City Council received a petition, signed by 87 concerned people, regarding the conditions at Wells Square and Bloemhof, nominally in the District Six area (Figures 5.1 and 6.9).83 Although this petition was not itself racially motivated, or discriminatory, it initiated a chain of events that led to segregation. The petition was a sincere response to the deepening social-spatial contradictions that the early colonization of the Cape had manifested. The petitioners were mostly from the streets surrounding Wells Square and their description of it was as follows:

Wells Square is the home of a number of prostitutes and criminals, many of the houses are brothels and shebeens kept solely for these purposes. The amount of liquor sold, mostly on Sundays, is amazing, last Sunday smuggling took place all day and at one time thirty drunken men were counted about. The respectable neighbourhood is awakened all hours of the early morning by the yelling emanating from Wells Square. Many of the houses are overcrowded and in our opinion are unfit for human habitation and ought to be condemned. Numerous complaints have been made to the Police who maintain that the only remedy is to condemn these dens.84

A surprise evening inspection by the Acting Medical Officer of Health (MOH) and seven inspectors on the 13 January revealed a few instances of ‘overcrowding.’ For example, ‘No. 47. Room III, with a capacity of 972 cubic feet was occupied by two adults and three children, this room having two children in excess,’85 as well as a few minor defects in paving of the yards, broken windows and door frames, and dirty walls. The Acting MOH was not convinced that the residences of Wells Square were ‘unfit for human habitation’ which would have been the only legitimate reason to remove people from the site. He felt they simply needed some remedial work.86 Nevertheless, the Deputy Commissioner of the South African Police, G.D. Gray, gave his reaction to the petition:

Undoubtedly the majority of the inhabitants of Wells Square are of a low social type, and it may fairly be described as one of the slums of the City … I quite agree that many of the houses are overcrowded and unfit for human habitation, and undoubtedly the insanitary dwellings, bad surroundings, and the one and two-roomed houses of Wells Square, in which the decencies of life are not possible, have a great deal to do with the criminal behaviour of its population, and very sensibly effect their present social condition … The remedy lies in sweeping away these slums and substituting for them healthy and cheap dwellings.87

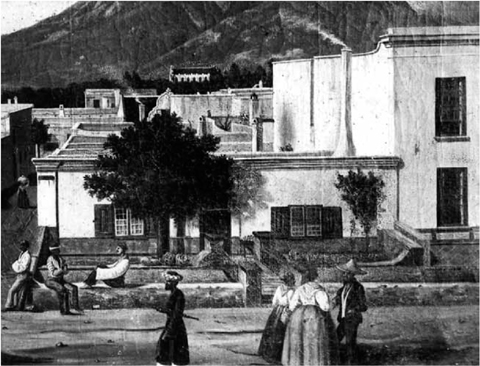

6.9 Wells Square, from Thom’s Survey, 1898

As we have seen in Chapters 4 and 5, the dense urban fabric of fractured and internalized space that the administrators of the city found so problematic from an aesthetic and social point of view, was embodied in Wells Square. The MOH distilled the ruling approach to such an ‘eyesore’ a few months later, in the very title of his report to the City Council’s Public Health Building Regulation Committee (hereafter PH&BRC): ‘Slum Property’. He urged action against ‘the parts of the City in which the houses are so congested and so badly arranged that it would be far better to clear the area on which the houses stand, lay it out afresh, and erect thereon proper dwellings.’88 The report instantiates state ambitions to actively set the disorder of the city straight, to erase and begin again, to ‘lay it out afresh’ and re-order those people and places inimical to the ruling fantasies animating the colonial project. That moralizing re-ordering impulse is the basis of all utopian schemes. Lived layers of complicated social history, the ongoing manifestation of people and places over time, which colonization’s creolization had brought, was to be remade in ways more seemly.89

In September 1916, the PH&BRC received another petition from residents in the vicinity of Wells Square. This time the signatures came from people resident as far away as Plein and Hope Streets.90 The MOH, Jasper Anderson, like the Acting MOH before him, considered that ‘the buildings themselves were in a fair sanitary condition.’91 Councillor I.J. Honikman suggested that ‘if the area were opened out the evil would disappear.’92 In a report dated 13 November 1916, the City Engineer submitted Scheme A and Scheme B on the proposed remodelling of Wells Square (Figure 6.10).93 Although Scheme A was adopted, both schemes were intended to expropriate and remove the buildings in the centre of the square and provide two electric lamps, with Scheme B intended to extend the existing road infrastructure through the site. No progress was made on the matter until December 1917,94 when the enrolled voters met to vote on a £34,000 extensive proposal to ultimately expropriate all the properties of Wells Square. Even though J.D. Cartwright proclaimed, to much cheering, that Wells Square was ‘acknowledged to be a great evil in our midst, and in the name of our fair city, in the name of our civilisation, and in the name of our Christianity it was our duty as intelligent citizens to say that such a foul spot should exist no longer,’95 the proposal was narrowly rejected on the basis of ‘Adequate Housing, then Demolition.’

The original Wells Square petition had led to an Overcrowding Sub-Committee of six councillors, including the MOH and the City Engineer, to consider ‘the question of making a recommendation to the Council to build cottages for their own employees, and to afford better facilities in the direction of City land being acquired for building cottages for the labouring classes.’96 It was the chance for the City to provide an edifying model for how its citizens ought to live, to secure a totemic housing project in support of the project of Empire. Or not. Their initial plan was to build 450 ‘cottages’ for municipal employees on municipal land dotted around the city. Workers were expected to rent the cottages at 6 shillings a week deducted from wages.97 A housing project on municipal land some six kilometres from the CBD in an area that would become known as Maitland Garden Village was the result. Although the Housing & Estates Committee had initially considered letting the cottages to ‘European or coloured employees of the Council who are in receipt of wages not exceeding 1/6d per hour,’98 it effectively became a Coloured neighbourhood.99

The City Engineer’s Phase One approach was hardly the apogee of Garden Suburb design (Figure 6.11).

6.10 Wells Square slum clearance proposal A (above) and B (below), 1916. Hatching indicates buildings to be removed. Note the two street lights indicated by ‘bulls-eyes’

6.11 Maitland Garden Village, 1919, Phase One on the left and Phase Two un-built on the right and Cottage Type B and C1

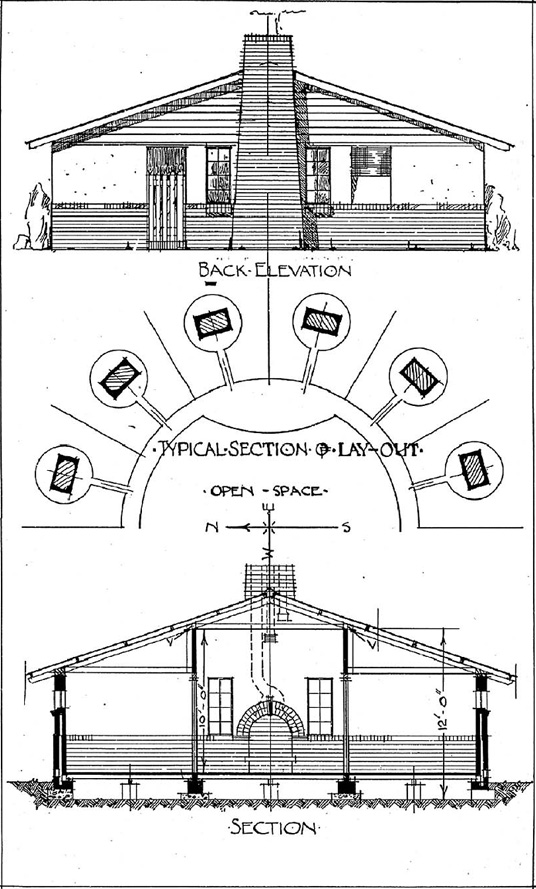

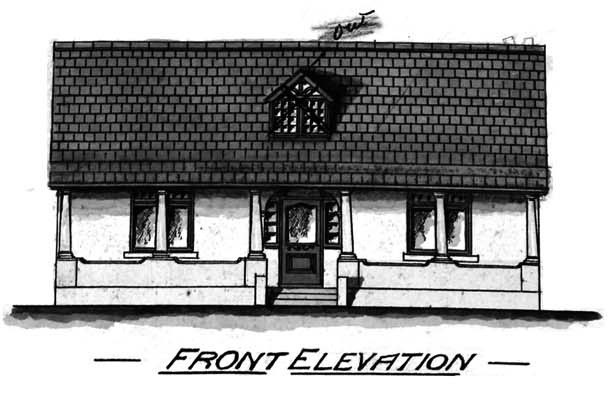

Apart from a central area for ‘recreation’ the project was simply a planning exercise in low-density semi-detached suburbia. A humanist bright spot was an attempt to alternate the house types ‘and so break the monotony.’100 The main interest that Maitland Garden Village holds is in the design and presentation of its ‘cottages.’ Significantly, Type B with its baroque gables shows the influence of the Cape Dutch revival at the time (as noted in Chapters 2 and 3). This relatively extravagant cottage was intended for the caretakers of the village and was suggestively located at the main entrance next to the recreation ground for both surveillance and hierarchical status. There is an Arts and Crafts sensibility evident in the Tudor-style of Type C1 of which 66 were to be built. Contrary to the recommendation of the Acting MOH for cottages of at least three rooms – because ‘relatives or friends, poor and unfortunate, will always be accommodated’,101 – the remainder of the site was distributed with 52 Type C2 two-roomed dwellings.

These cottages were designed by the City Engineer’s architectural assistant G. Angelini, and were showcased in the Municipal Journal in 1919,102 presumably to illustrate the possibilities for municipal contribution to social housing. The illustrations represent the dual desires of the age very clearly: the perspective view at the top with wisps of smoke and a well-kept garden hints at a Romantic rural idyll sentimentally lost to England’s past, whilst the plan above, with labelled spartan rooms and minimum dimensions, describes a calculated scientifically determined conception of correct living in the modern world. The insistent line of the dimension string chimes with the wisps of smoke; they bolster each other through the neurotic representational moves of discourse. As the eye travels between the two radically different representation techniques, from orthographic drawing to perspective and back again, the fantasy of remaking the city’s Others in the image of the Self is emboldened, doubled. These overcompensating dual rationalities anxiously refuse to be informed by the complicated social reality of the city.

Whilst the cottages of Maitland Garden Village were being built, the Housing & Estates Committee and the Overcrowding Sub-Committee looked to new sites for further development with the assistance of the architect Frank Kendall and other members of the Cape Institute of Architects (CIoA),103 although it seemed fairly certain that the Committee would favour extending Maitland Garden Village into a ‘model village.’104 At a meeting of registered municipal voters, recovering from the recent and deadly influenza epidemic, the extension of Maitland Garden Village and a similar scheme at the top end of Roeland Street in the City Bowl were overwhelmingly approved with a loan of £250,000.105 Death, it seemed, was a stronger motivator than fiduciary prudence. Delbridge and Hawke, as representatives of the CIoA, framed the rules and requirements for these schemes and were the judges of the open competition that followed.106 The winners of the layout design were J. Lyon and W.A. Ritchie Fallon, whilst J. Perry and F.M. Glennie were winners of Type B, D and E, and Type A and C cottages respectively.107 John Perry, who also went on to win the initial layout of the Pinelands Garden City, had visited Wells Square a few years before as a consultant to the Municipal Reform Association, advising on the physical problems of the area.108

6.12 Roeland Street Housing Scheme, 1919 with Type A cottages

6.13 A close up of old Cape Town, Langschmidt, Long Street in 1844

6.14 Wells Square and Roeland Street Scheme – relative densities (notes by the author), aerial photo 1926

Although the Maitland Garden Village extension, or Oude Molen Scheme in a later incarnation, was quashed through pressure by the representatives of the Pinelands Garden City and others,109 it does suggest, with its curvilinear streets, low densities and central civic zone, a Garden Suburb-inspired vision of social housing. The design for the Roeland Street scheme showed similar attributes, though due to the hilly nature of the site and its fairly close proximity to the city centre, it contained only a school as part of its civic infrastructure. Notably, the Housing & Estates Committee referred to the Roeland Street scheme as a ‘village,’ underlining its anti-urban basis despite, or rather, because, of its proximity to the city centre. Indeed, at 8 dwellings to the acre, the layout was low even for Garden City ideals. It was also explicitly reserved for ‘European Employees of the Council’ half way through its construction.110 Though Maitland Garden Village was not ostensibly inspired by segregationist ideals, only five years later it was clear that the Council had already begun to see its employees as divisible into distinctive racial groups. Though segregation as a customary ordering principle had been gathering momentum over the preceding ten years (as we saw in Chapter 5), it became an official requirement of the state’s Central Housing Board whose money was used in the development of the Roeland Street Scheme (Figure 6.12).

The later racial designation of the Roeland Street Scheme would not have been known to Glennie when he designed it but the type of cottage he imagined is suggestive of prevailing social attitudes. Although without gables, it has many of the design attributes of workers’ housing on a Cape Dutch homestead or that of the BoKaap houses across Table Valley, as if Glennie was referencing the Cape’s ‘feudal’ history (Figure 6.13). This was a common design strategy within the Garden City Movement and its Arts and Crafts inspired architecture. Certainly, its design was purposefully construed – the monopitch concrete roof was decisively not in line with the double-pitch required by regulation 964 of the 1920 building regulations.

The densities of the Roeland Street scheme c.1926 compared to that of Wells Square are very different (Figure 6.14). The contrast makes clear that whatever Romantic vision may have driven Glennie’s design, it was to be set within the low-density, anti-urban ethos of the Garden City Movement, not the dense fabric of Old Cape Town. The aerial photograph of 1926 depicts the Roeland Street buildings as positive objects set starkly against an almost bleached empty space, whilst Wells Square is objectless and internalized, resembling Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of a ‘smooth space.’111 Roeland Street is highly territorialized, with each unit identifiable, nameable, and easily surveyed. It gets at Empire’s ambitions for a categorical and singular taxonomic cohesion between space and subject – it was for White employees of the City and its segregated form and space removed any ambiguity in this regard. The production of the city as a White space is literally embedded in the spatiality of this small-scale housing project.