6

Modernism and the Liturgical Movement

The year 1960 was a watershed in the creation of a modern Catholic church architecture, not least because it was then that one of the most important books for church design of the twentieth century was published. Peter Hammond’s Liturgy and Architecture set out for architects and clergy the case for a modern church architecture based primarily on the function of liturgy. Hammond argued that the basilican form of church had developed in the Middle Ages to enshrine an excessively clerical liturgy remote from the congregation. Instead, he urged a church architecture that promoted congregational involvement, a ‘corporate worship’, which, he thought, would recapture the spirit of early Christian liturgy.1 The Anglican church of St Paul at Bow Common in London by Robert Maguire and Keith Murray opened the same year and was widely published in connection with Hammond’s arguments. The book and the building contributed to an architectural discourse that outlined a new approach to church design, drawing from the liturgical movement in the Roman Catholic Church, already then gaining ground in Britain, and substantially influencing architects and clergy in the design of Catholic churches. This chapter examines some pioneering examples of architectural and clerical collaboration in producing this new liturgical architecture.

Hammond’s book was polemical in tone and arose in the context of an organisation he helped to found in 1957, the New Churches Research Group (NCRG). Most of this group’s members were young architects, and they met regularly in the basement bar of the Architectural Press offices in London. Catholic architect Maguire and his colleague Murray, an ecclesiastical designer, were founding members. Also involved was Catholic architect Lance Wright, frequent contributor to The Tablet and technical editor for the Architects’ Journal, giving the group access to professional publications. As the NCRG publicised its ideas in the 1960s, its membership expanded, including John Newton of Burles, Newton & Partners, designer of a large number of Catholic churches in London, and Austin Winkley, a Catholic church architect and lay activist. Patrick Nuttgens, Patrick Reyntiens and Liverpool architect Peter Gilbey were also involved. The group was interdenominational, later also including Anglican church architect George Pace among its members. Clergy were also present. Hammond himself was an Anglican priest and theological writer.2 Charles Davis, a Catholic priest and theologian teaching at St Edmund’s Seminary at Ware was an early participant. Most founding members of the NCRG were young and sympathetic to the emerging avant-garde architectural discourse of the New Brutalism, and indeed Peter Smithson was invited to speak at an early meeting. The NCRG and New Brutalism had much in common: theoretically, in their rejections of prevailing conventions in architecture, and socially, as groups of ‘angry young men’.3

The NCRG organised lectures and conferences and undertook a campaign of publication.4 Following the publication of Liturgy and Architecture, Hammond edited a book of talks given by early group members including Wright and Davis, entitled Towards a Church Architecture in evocation of Le Corbusier’s manifesto of modern architecture.5 Meanwhile the quarterly magazine Church Buildings Today, started in 1960 by publisher John Catt, began its first issue with a polemical article by Maguire and Murray summarising Hammond’s demand that architects understand the functions of a church from first principles.6 For a few years Maguire and Murray edited the magazine, changing its name to Churchbuilding. It acted as a forum for debate amongst members of the NCRG and others, including critical accounts of new buildings in Britain and abroad. Another group had an equally important and related role: the NCRG’s aims were shared by the Institute for the Study of Worship and Religious Architecture at Birmingham University, founded around the same time and led by Anglican theologians Gilbert Cope and John Gordon Davies. This academic organisation also contributed to Churchbuilding and organised tours and lecture series that complemented the NCRG’s activities.

Meanwhile Lance Wright also wrote reviews of churches, sometimes anonymously, for the Architects’ Journal, further propagating the group’s thinking. Under his chairmanship from 1964, NCRG members published a series of functional studies of each denomination’s requirements in the Architects’ Journal, issued in book form as a ‘briefing guide’ in 1967, a publication that fulfilled Hammond’s original call for a ‘liturgical brief’.7 Wright also organised a conference on Roman Catholic church architecture attended by 60 architects that, at Cardinal Heenan’s suggestion, produced a guide for clergy and architects involved in reordering existing churches.8 Wright’s practice, in which Peter Ansdell Evans and Nigel Melhuish were also partners, went on to design three small Catholic churches in the late 1960s, St Cecilia, Trimley; St Gregory, Alresford; and Christ Our Hope, Beare Green, all incorporating NCRG principles: indeed Trimley was really a collaborative and experimental design by the Catholic group in the NCRG.9 The group’s work was not only confined to architectural discourse, however. When Charles Davis became editor of the Catholic Clergy Review in 1963, he substantially changed its tone, commissioning critical reviews of new churches, many written by fellow group members including Wright, Nuttgens and Winkley. Beginning as a relatively informal avant-garde organisation, therefore, the NCRG embarked on a successful campaign of publication which soon made modern church architecture synonymous with the liturgical movement.

The group had two core ideas: an emphasis on functional analysis as the primary determinant of architecture and a concept of the liturgy as a communal act undertaken by the whole congregation. Church architects, they insisted, had to analyse liturgy as the church’s primary function. Yet rather than enshrine existing rites, architects were to employ an ideal concept of liturgy. Modern church architecture therefore had an agenda of religious and social reform.10 Congregational involvement in the liturgy was the primary aim, since the original, authentic purpose of liturgy in early Christianity was thought to have been the collective, participatory worship of God by everyone present. The new concept of liturgy would be socially liberating: ‘We still have to face the fundamental problem of restoring to the Christian layman his true priestly liturgy – both in and out of church’, wrote Hammond, ‘and of overcoming the psychological proletarianism that is part of the legacy of the Middle Ages’.11 Thus modern church architecture would bring dignity to the laity with their involvement in worship. New spatial forms could change the congregation’s perception of itself and its role in liturgy, affecting people’s behaviour. The altar had to be close to the congregation; divisions between congregation and sanctuary had to be reduced, though a hierarchy of spaces was still preferred; distractions from the Eucharistic liturgy had to be removed; and the faithful were to be brought into relation with each other as an ‘organic unity’.12

If liturgical function was the most important aspect of a church, symbolism therefore took second place. Hammond discouraged overt symbolism or expressive design in a pointed reference to Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral and certain recent American churches:

Churches are built to ‘express’ this and to ‘symbolize’ that. We have churches which look like hands folded in prayer; churches which symbolize aspiration or the anchor of the industrial pilgrim’s life; churches which express the kingship of Christ; churches shaped like fishes, flames, and passion-flowers. There are still very few churches which show signs of anything comparable to the radical functional analysis that informs the best secular architecture of our time.13

Artworks were also considered with caution as potential distractions from the liturgy. Coventry Cathedral, for Basil Minchin writing in Churchbuilding, employed modern art for mere ‘religious sentiment’, becoming a ‘museum of religious art’, while the domination of the church by Sutherland’s tapestry detracted from the altar.14 Even church towers were suspect, ecclesiastical clichés now that they no longer served their original functions.15

The principles of architectural modernism resonated with those of liturgical reform and scholarship. Hammond wanted to restore a supposedly primitive and pure idea of liturgy, recovering its fundamental principles. Likewise the architecture of the church could be analysed for its principles: ‘Reduced to its bare essentials, it is a building to house a congregation gathered round an altar’, he argued, and his simple but potent diagrams claimed to show how a congregation would arrange itself if unconstrained by architecture or convention.16 Liturgical historians such as Jesuit Josef Jungmann and Anglican Gregory Dix had sought the underlying stable principles of the liturgy beneath its historically shifting surface appearances: the ‘primitive picture’ of worship, as Jungmann put it; Dix’s ‘shape of the liturgy’.17 Modernist architects also proposed to discard the inessential. Siegfried Giedion, for example, had divided architecture into ‘constituent’ and ‘transitory facts’: the latter were ephemeral characteristics and motifs across history, and the former were the stable underpinnings of architectural form that architects had to identify in developing a ‘new tradition’.18 To divest themselves of acquired but unnecessary habits in design, architects increasingly studied social activities, often through diagrams like Hammond’s, to design buildings as sheltering envelopes for essential functions. The aesthetics of modern architecture continued this essentialism by rejecting ornament in favour of plain materials and volumes, revealing the human activities they contained.

Hammond’s ideas therefore resonated with those of young brutalist architects, who maintained an idealistic social agenda and felt that modern architecture itself needed to return to its principles. The Smithsons and other members of Team 10 published polemical articles arguing that architects had to consider human social groups and communities as the primary motivations in design:

Architecture is concerned with finding the pattern of buildings and communications which make the community function and, at the same time, give it meaning. To make the community comprehensible to itself, to give it identity, is also the work of the politician and the poet, but it is the work of the architect to make it visible.19

Similarly, for the founders of the NCRG, the church architect’s task was to effect and reveal the community of the faithful brought together in worship.

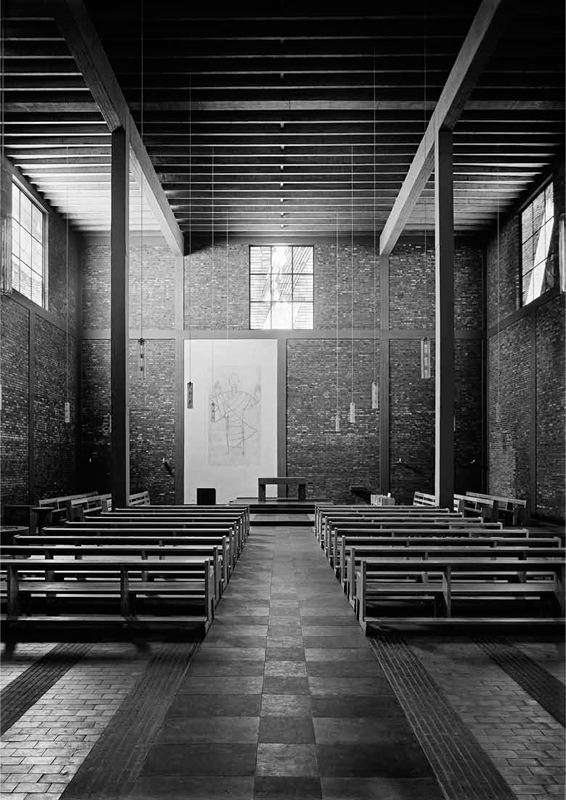

The NCRG’s ideas led to an interest in alternative European precedents in church architecture, shifting attention from France to Germany. While Le Corbusier’s handling of materials remained influential, his religious architecture was seen as liturgically conventional. ‘Ronchamp’, wrote Maguire and Murray, ‘has provided a justification for architects to ignore any discipline, to pursue private whimsy without concern for function …. In the development of church building, it is a blind alley.’20 Instead, Hammond and his colleagues looked to Rudolf Schwarz, who had been designing churches since the 1920s for the Diocese of Cologne based on theological and liturgical study, using modern construction techniques and an austere approach. Hammond illustrated Schwarz’s pre-war churches of Corpus Christi at Aachen, completed in 1930, praising the essentialism of its white walls and prominent altar, and St Albert, Leversbach, of 1932, a ‘liturgical shed of the utmost simplicity for a small rural community’.21 Similarly, highlighting buildings from a trip to Europe organised by the Birmingham Institute in 1961, Gilbert Cope and Giles Blomfield praised Schwarz’s new church of St Christophoros at Niehl, an industrial suburb of Cologne (Figure 6.1):

The church at first seems as harsh as its surroundings; in fact it is a salutary reminder of the essentials of the Christian faith. Here is a severely simple eucharistic room; the crude expression of the plain brick box derives from the singleness of purpose, clearly understood and fulfilled. … The great value of the building is to remind us what a church is really for; the place where the community meets to offer worship.22

6.1 St Christophorus, Niehl, Cologne, by Rudolf Schwarz, 1958–60. Stained glass and painting of the Risen Christ by Georg Meistermann © DACS, London, 2013. Photographer unknown. Source: © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

For post-war British church architects, Schwarz was a model for the integration of architectural modernism and liturgical thinking.

Schwarz had been associated early in his career with the Catholic liturgical movement through contact with Romano Guardini, theologian and author of The Spirit of the Liturgy, for whom Schwarz had designed a small chapel at a Catholic youth centre in a castle at Rothenfels. Schwarz’s first book, Vom Bau der Kirche, translated for an American publisher as The Church Incarnate: The Sacred Function of Christian Architecture, was especially powerful for modern architects because of its abstracted diagrams of relationships between congregation, celebrant and God.23 Like Hammond later, Schwarz wanted to consider the church’s fundamental needs:

Table, space and walls make up the simplest church. The little congregation sits or stands about the table. … We cannot continue on from where the last cathedrals left off. Instead we must enter into the simple things at the source of the Christian life. We must begin anew and our new beginning must be genuine.24

For Schwarz, however, the purpose of this analysis of liturgical space was more symbolic and mystical than British architects’ often more strictly functionalist approaches.25 Though sometimes creatively misread by British writers and architects, Schwarz’s architecture indicated a path for reform.

Other German architects, especially Emil Steffan and Dominikus Böhm, were also influential. These architects and their clerical clients engaged with a political discourse in Germany of community cohesion: worship, and therefore church architecture, it was argued, should bring people together to counteract the tendency to anonymity in modern urban life.26 Their approach made them especially attractive to British church architects inspired by the New Brutalism and liturgical thought. Italy could provide further inspiration: Joseph Rykwert, for example, argued as early as 1956 for a church architecture based on programmatic analysis, praising the circular-naved church of S. Maria Nascente in the experimental housing district of QT8 in Milan.27

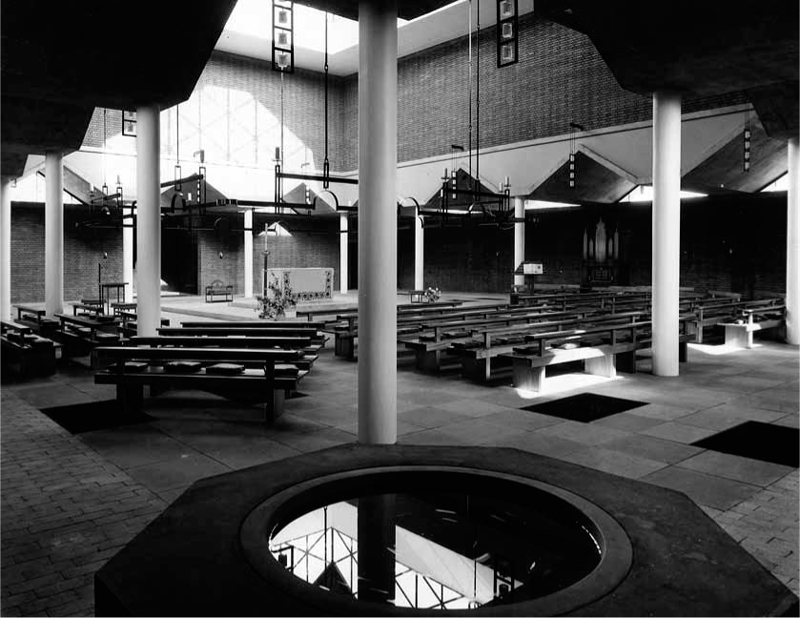

Maguire and Murray’s Anglican church at Bow Common explored these emerging concepts, working them out through practice. Maguire and Murray benefited from collaboration with their client, Gresham Kirkby, an Anglo-Catholic and socialist with knowledge of the European liturgical movement.28 In the temporary hall used before the church was built, Kirkby had developed liturgical forms that attempted to embody an idea of communal worship: at communion the congregation gathered, standing, around the altar, each member receiving the Eucharist before the whole congregation returned to their seats, and congregational processions were also encouraged.29 Maguire and Murray incorporated these practices with a broad plan, slightly longer than it was wide, a processional route around its edge marked with paving slabs and defined by reinforced-concrete columns and a vaulted ceiling; the altar was placed off-centre under the lantern, on a low platform in an open sanctuary, and the seating was set back from it around three sides allowing room for communion (Figure 6.2). A metal ciborium added shortly after the opening in 1960 enhanced the altar’s presence. Maguire and Murray described their church using similar spatial and mystical terms to Schwarz:

6.2 St Paul, Bow Common, London, by Robert Maguire & Keith Murray, 1958–60. Photograph taken on completion c.1960 but before installation of the ciborium. Photo: Eric de Maré. Source: Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Library Photographs Collection

The liturgy may be seen as a movement towards the place of the altar; in other words the incorporation of the individual person into the sacrificial life of Christ, or movement towards the transfiguring light. … A church is the place of the assembly of the people of God. It is a holy place, consecrated, set apart, for this purpose.30

Bow Common went some way beyond Hammond’s more severely functionalist intentions, retaining High-Church notions of sacred space and sacrifice. Yet it provided a convincing and widely published model of a liturgical modern church architecture, and did so with a brutalist material expression that emphasised fundamental characteristics.31

Hammond’s Liturgy and Architecture had received some criticism, even from sympathisers, for its almost exclusive emphasis on the Eucharistic rite. Cope wrote that the church was ‘a liturgically dual purpose volume’, its other most important function being to accommodate baptism.32 His colleague at the Birmingham Institute, Davies, was just then working on a book about the architecture of baptism for Hammond’s publisher.33 At Bow Common, Maguire and Murray made baptism a significant element in their design, with a prominent font placed near the entrance in one corner of the church’s processional circuit, symbolising the sacrament as the entrance into the kingdom of God, as Davies later urged in his book. Yet Bow Common was also criticised for reductivism, since it did not include any permanent place for readings, contradicting many Anglicans’ emphasis on scripture.34

Bishop Beck of Salford warned Catholics against taking Hammond too literally: Catholics, he wrote, differed from Protestants in viewing the liturgy as a ‘sacrifice of propitiation’ rather than solely a commemoration of the Last Supper, a distinction that he thought ‘is bound to affect not only the liturgy of worship but the character of the building in which that worship takes place’. He supported Hammond’s arguments, but gave them a Catholic inflection: ‘We must seek to build churches which will be adapted to the needs of a more consciously corporate worshipping community, performing in its own locality through the power of its own priest the sacrificial action of the Mystical Body of Christ’.35 This complexity was also present in the liturgical movement itself as it developed in the Roman Catholic Church in the twentieth century until its eventual acceptance at the Second Vatican Council. Liturgical reformers received qualified approbation from Church authorities, and were already influencing Catholic church architecture in Britain when the NCRG was established.

THE LITURGICAL MOVEMENT IN THE CHURCH

The liturgical movement originated in the nineteenth century when new scholarship on the history and theology of liturgy resulted in a desire to change liturgical practice.36 In the early twentieth century, the Benedictine abbey of Maria Laach in Germany pursued liturgical theology and innovation, becoming a centre for conferences and publications. Influenced by early Christian writers, Abbot Ildefons Herwegen and fellow monk Odo Casel insisted on the liturgy’s central place in the Church, which they described as the ‘Mystical Body of Christ’ composed of all its members. Liturgy, it was argued, brought the Church together to constitute this body, and Christ became present in the congregation through their gathering to effect redemption. An influential moment in the liturgical movement was a Mass said by Herwegen at Maria Laach during a conference in 1914: a wooden altar was placed in the church’s crypt, the celebrant faced the people, and the congregation recited parts of the Mass together.37 The ‘dialogue Mass’, as it was known, became widespread in Germany after its approval in 1929.38 Meanwhile historical studies such as Jungmann’s Mass of the Roman Rite argued that the liturgy’s history was characterised by gradual formalisation and ceremonial enrichment, trends that made it increasingly clerical and detached from the congregation, who were reduced to ‘spectators looking on at a mystery-filled drama’. The early Christian Mass, in contrast, had been fluid and extemporised, characterised by a ‘community spirit’, a ‘feeling of oneness’, now lacking.39 The historical study of liturgy and its architectural settings showed its variety and contingency, opening the way for reform.

A further development in the liturgical movement took place in France, where parish clergy developed the idea of a ‘pastoral liturgy’ that could educate the laity in its meanings as it was performed. The Centre de Pastorale Liturgique was founded in Paris in 1943, promoting this concept through conferences and its journal, La Maison Dieu.40 In France the worker-priest movement saw priests assuming working-class occupations as a missionary technique, and ‘Catholic Action’ was especially strong, a movement to involve the laity in all aspects of parish organisation and evangelisation. Missionary approaches were applied to ordinary city parishes. Henri Godin, a priest in a Paris suburb, argued that the majority in his parish were not effectively Christian and needed conversion. For that to work, Christian worship had to be adapted to the culture of the urban poor. ‘Our religion must be religion pure and simple’, argued Godin, ‘stripped bare of all the human adjuncts, rich though these may be, which involve a different civilisation’.41 The Mission de Paris followed, a programme of missionary activity, including plain-clothes priests who declared a spirit of poverty, a communal social view of the parish and adaptations of the liturgy and its setting, including Mass in parishioners’ houses.42 Dominican theologian Yves Congar followed these developments closely, and his book Lay People in the Church consequently argued for a central role in the Church for the laity, including in the liturgy.43 The Mission de Paris became well known and influential in Britain, directly influencing Kirkby at Bow Common, for example. The missionary and pastoral approach had important implications for church architecture, which had to provide for an engaging and communal liturgy, but to do so in a spirit of poverty and an awareness of context.

All these movements were independent of the Vatican. The Vatican generally endorsed and encouraged the liturgical movement, allowing moderate developments and adopting many of its proposals through incremental reforms of Church regulations and liturgy while condemning extreme views and experiments. Pius X, on acceding to the papacy in 1903, affirmed the primacy of Gregorian chant for liturgical music, encouraging the laity to form church choirs to restore this ancient liturgical function, and he urged the faithful to receive frequent communion as the highest form of participation in the Eucharist.44 Pius XII, in office from 1939 to 1958, took great interest in the liturgical movement and confirmed its most important principles. His encyclical of 1943, Mystici corporis Christi, endorsed the concept of the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ, and in Mediator Dei he encouraged the ‘active participation’ of the faithful in liturgy, with ‘earnestness and concentration’.45 The Vatican made significant liturgical changes during his office, including the formalisation and dissemination of the dialogue Mass.46

The Second Vatican Council, begun by John XXIII and continued by Paul VI, brought the liturgical movement to maturity within the Church. The ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ of 1963 enshrined its principles and announced the reform of the liturgy that took place over the following years, culminating in the new rite of Mass in 1969. The constitution asserted the importance of lay participation and the pastoral nature of liturgy. The liturgy and sacraments had to be ‘restored’, becoming simpler and more accessible: ‘texts and rites should … express more clearly the holy things which they signify. Christian people, as far as possible, should be able to understand them with ease and to take part in them fully, actively, and as befits a community’. Taking its cue from missionary concerns, the constitution encouraged regional diversity, permitting bishops to make alterations relevant to their contexts and encouraging the incorporation of local cultural forms in sacred rites and liturgical objects and furnishings.47 Behind the making of the constitution were theologians and liturgy scholars at the centre of the liturgical movement, including Congar; voting to implement it at the council in the nave of the basilica of St Peter’s in Rome were all the Catholic bishops of the world.

In Britain, knowledge of the liturgical movement before the 1950s was limited and arrived mainly through papal pronouncements: Pius X’s statements led to widespread galleries in churches for lay choirs, the elimination of aisle seating so that congregations had unobstructed views of the altar and broad sanctuaries so that large numbers could kneel at the communion rail, all still important in the 1950s.48 Before the Second World War, the few British Catholics who noticed the liturgical movement tended to be regarded as eccentric. Amongst them was Eric Gill, who wrote an essay on the subject, ‘Mass for the Masses’, published for a Catholic socialist magazine in 1938. Gill argued that the altar should be in the centre of the church, as a symbol of sacrifice: ‘not only does Christ offer Himself in the Holy Sacrifice, but the people also offer themselves. It is a corporate offering’, he wrote. Bringing the laity into such a relationship with the altar required new spatial forms, eliminating hierarchies, so that Christianity could ‘become again the religion of the people, the common people, the masses’. Architecture could help to achieve this: ‘the altar must be brought back again into the middle of our churches, in the middle of the congregation, surrounded by the people’, and the church should be plain and humble.49

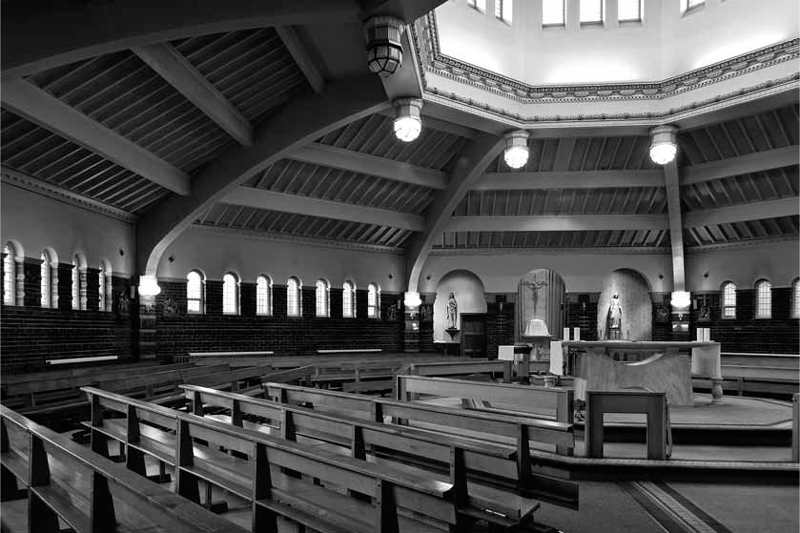

Gill implemented these ideas in the church he designed with parish priest Thomas Walker, St Peter at Gorleston-on-Sea, a simple brick barn-like building opened in 1939, a cross in plan with transepts filled with seating so that the congregation was arranged on three sides of the altar. Another parish priest who was friendly with Gill was John O’Connor, whose chapel-of-ease of Our Lady and the First Martyrs in Bradford, built in 1935 by local architect J. H. Langtry-Langton, sited the altar at the centre of an octagon, the congregation arranged around it (Figure 6.3). Despite their innovations, neither church attracted much attention until the 1950s, when they could be viewed as precursors by Hammond and the NCRG and, perhaps, by certain former bishops of Leeds who knew the church at Bradford: John Heenan as archbishop of Liverpool and later of Westminster and George Dwyer, who became archbishop of Birmingham.

By the 1950s, British awareness of the liturgical movement was growing and the Vatican was reported to be favourable to reform.50 Clergy with international connections played an important role in disseminating the movement.51 Clifford Howell, for example, a Jesuit and former missionary, wrote on the liturgical reforms for Catholic newspapers, and published The Work of Our Redemption in 1953, a colloquial guide to the Mass for the laity. This work arose from his involvement with the American Benedictine journal, Worship, published by the monks of St John in Collegeville, who were at the forefront of liturgical thought in that continent thanks to their connections with German monasteries.52

Another important figure was James Crichton, parish priest at Pershore in Worcestershire, where he undertook a small but significant architectural experiment. Crichton was an early member of the Society of Saint Gregory, founded in 1929 to promote the revival of Gregorian chant, its interests soon expanding to the liturgy itself, and he edited its journal, Liturgy, from 1952, becoming an important writer on the subject.53 Crichton followed developments in Europe closely, travelling to the continent for conferences. In 1953, he went to Lugano for the International Congress on Liturgy, which proposed liturgical reforms around the theme of ‘active participation’ and where Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani of the Vatican celebrated Mass facing the people.54 In 1956, Crichton went to Assisi to attend perhaps the most important post-war conference of the liturgical movement, the International Congress on the Pastoral Liturgy, whose keynote speaker was Pius XII. Crichton attended with his superior, Archbishop Francis Grimshaw of Birmingham and the expert on canon law and liturgy, O’Connell, who summarised the conference for the Clergy Review.55 On returning to Pershore, Crichton began to implement liturgical movement ideas in the design of his new church.

6.3 Our Lady and the First Martyrs, Bradford, by J. H. Langtry-Langton, 1935. The interior has been reordered twice, most recently in 1971 by Peter Langtry-Langton to restore aspects of its original arrangement. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2009

A decade before, he had already written a description of his ‘dream church’ for the Society of St Gregory. Beginning with a complaint that architects did not adequately consider the liturgy in their designs, he set out the primary functions of the church building, summarising liturgical movement theology in relation to architecture:

A church is a miniature of the Mystical Body, a concrete realisation of the heavenly Jerusalem. … It is a cell of the Catholic Body, it is the ecclesia, the meeting place of the people of the parish. … The church exists to make possible the due performance of the principal acts of the Christ-Body. The chief of these is the Eucharist, the Action par excellence of the Church. The altar, then, which is the place of sacrifice, becomes the centre of the church, not merely in the sense that all can see it but, because the sacrifice is also the people’s sacrifice … in the sense that the people can gather round it.56

The remainder of the article proposed a church building, including a plan (Figure 6.4). The church would be a domed circle, the altar off-centre in the central part, the seating arranged in a crescent in front of it and to the sides; the altar, he thought, should not be in the centre because the congregation had to be addressed directly by the priest in the liturgy. The sanctuary was to be lower than the nave, but the altar elevated so that it appeared to be at floor level while retaining a modest separation. The altar would be intended for Mass facing the people and the tabernacle placed in a chapel behind the nave. A choir, leading the congregation in liturgical chant, would be located behind the altar. Instead of a pulpit there would be two ambos, a feature taken from early Christian basilicas, for reading the Epistle and the Gospel directly to the congregation instead of facing the altar as the liturgy then required. A broad circuit around the edge of the nave was marked off by columns and devoted to ‘solemn processions’. The baptistery would be given a prominent place at the entrance, the holy-water stoups placed alongside it so that when people entered the church they would be reminded of this sacrament of initiation. Side chapels would allow private devotions to be pursued away from the nave so that they did not detract from its liturgical functions. All these innovations became commonplace after Vatican II, though Catholic rules on liturgical furnishings prevented many from being implemented earlier.57

At his church of the Holy Redeemer at Pershore, Crichton partially achieved this model in 1959 with the help of architect Hugh Bankart (Figure 6.5, Plan 4d). The church was simply built with red brick and stone trim, necessarily cheap in this rural parish. A steel roof structure gave a broad span over a single interior space. The sanctuary was placed within the main body of the church halfway into the two blocks of seating. ‘The whole purpose of the square plan is to gather all the people around the Altar and as close as possible to it’, wrote Bankart, adding that the altar was designed so that Mass could be said facing the people if it were ever to be permitted.