Let us start with the idea that architecture is first of all the space within, rather than the object we see, as Lao Tzu suggested 2,500 years ago:

Shape clay into a vessel

It is the space within that makes it useful

Cut doors and windows for a room

It is the holes which make it useful1

The fundamental questions for me are:

- How do we form spaces appropriate to their use?

- How do we connect these spaces together?

- How do we guide and concentrate view and light, so that we wake up to a connection with nature, with the world of nature outside?

- How do we bring out the potential drama of the site?

- How does this drama unfold as we move through the building, like moving through a landscape?

I will describe some buildings from the past that I particularly like, before discussing these aspects of the design within the context of the Wales Institute for Sustainable Education at the Centre for Alternative Technology (CAT).

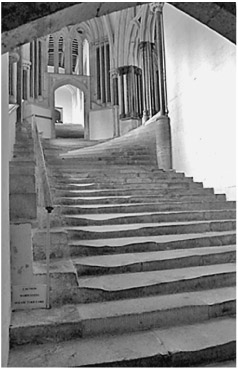

In the north transept of Wells Cathedral, a stair rises up to the Chapter House, which dates back to 1320 (Figure 1.9.1). You want to follow the footsteps worn into the stone from 700 years of use. They all go to the left, where the handrail is: you tend to swing to the outside of a spiral staircase anyway. The entrance to the Chapter House is up to the right, where the stair divides. As you emerge from the doorway out of the transept, more and more of the roof is revealed, and you can see the structure of the vaults, a preview of what you will find in the Chapter House. As you come up the winding stairs, they seem to build up, like a wave about to break. The Chapter House floor is at eye level as you approach, and you can see, in a very concentrated way, how the central column is rooted in the ground, like a tree.

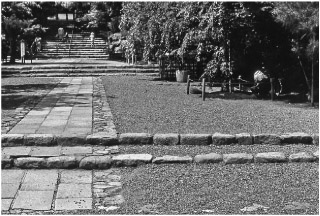

About 130 years later, in the 1480s, the Ryoanji temple was built on the northern side of Kyoto in Japan, at a point where the ground gently rises. The temple contains a famous and beautiful rock garden, and Figure 1.9.2 shows its approach. The route up the gradual steps is very carefully considered. First, there are two steps, then three, and it gets steeper as you approach the entrance. The architect did not expect people to march up there on axis; it was a place to wander up, because you can see that it has been made comfortable, with flat stones, which lead on to steps, and then you end up on gravel. You are expected to stop and think a bit, and then move left and go on up, and the entrance is just at the top, where the white panels are. At that point is a glimpse into the rock garden, of pleasures to come, although you cannot actually enter. You progress further and arrive at a little network of courtyards, much more domestic in scale. That is the living accommodation. You glimpse it before you turn left to regain the courtyard view. Its gravel is raked every day, and the rocks are placed in the most mysterious relationships. You are encouraged to sit on the veranda and meditate. As you think about the rocks, they change their scale and become quite enormous in your imagination. Behind them is a fantastic wall, which is apparently a national treasure, and so nobody is allowed to touch it. It is just a rendered wall, aged in a beautiful way. If you turn through 180º, you can look right through the building, and you see something nice happening to the left, and so you are drawn around to the west-facing veranda. It is a wonderful place to sit. It tells you there is something worth seeing to the left, as you are encouraged to linger. It is well sheltered from the weather, which reveals something of the climate. The scale is beautifully judged: the rail above the sliding screens is a little over 6 ft (1.8 metres), and the extra height above gives the space a sense of generosity and nobility. It has a very human scale, but also a grandeur about it, built with complete simplicity, no decoration at all, and all of clay and plants, and so infinitely recyclable. The view to the west is a counterpoise to the gravel and rock garden, beautiful in the evening, when the sunlight comes through the leaves of the birches to throw dappled light on the moss.2

The Villa Maser, by Palladio (Figure 1.9.3), was built about 1560, part of the redevelopment of the Venetian countryside. Mercantile power was under stress, and wealthy families were turning their attention to their own resources, inspired by the Roman ideal of harmonious living and working on the land. Palladio’s villas were derived from farmhouses. This is actually a very extravagant one: most were much more stripped down, in fact more like farmhouses. Maser is ennobled by symmetrical pavilions and by the porticos used for drying and storing food. It’s on a gentle hill confronting the landscape, and it suggests that you enter in the middle, but you do not. You actually enter down the side, down the porticos. The plan shows how that works. The most important living rooms occupy the central block, and the bedrooms occupy the cross wings. When you go along the colonnades, you see the staircase going up ahead of you to the piano nobile. Once you arrive there, you have a choice: if you walk left, you are up in the air, looking out over the well-farmed valley; go right and you enter a secret shady garden, embedded in the hillside. There is a fountain and a grotto, the source of water for the villa. The bedrooms open on to this completely private space. This villa has quite a wonderful spatial movement, progression and experience.

The WISE Project

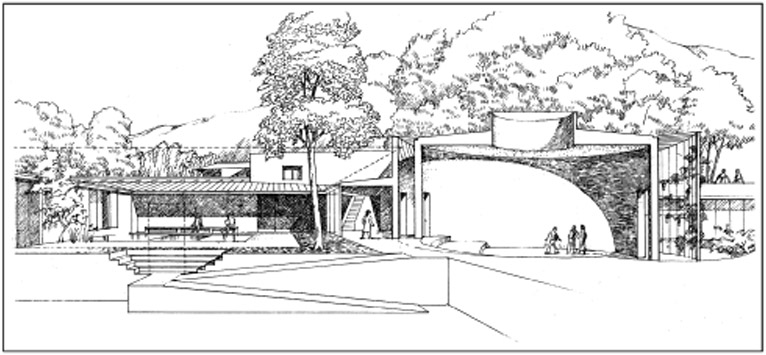

Figure 1.9.4 WISE building: cut-away perspective drawing by David Lea, showing courtyard, round lecture theatre and the intended ramped entry

Source: Drawing by David Lea

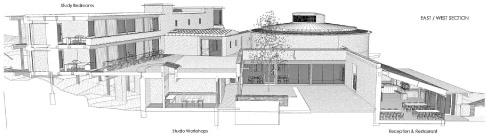

Figure 1.9.5 WISE building: the final section of the building, east to west, showing courtyard with lecture theatre behind and bedroom wings surrounding upper terrace

Source: Computer Projection by Pat Borer

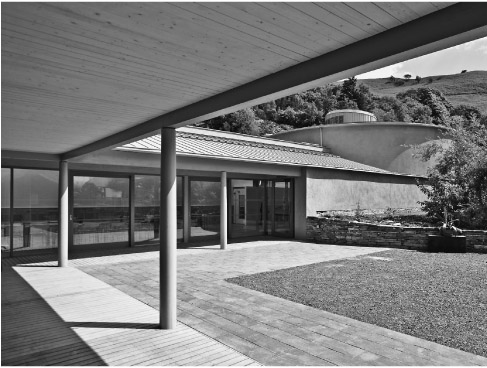

WISE was designed and built in partnership with Pat Borer and completed in 2010. It sits in a wooded valley, with its back to an old slate tip. You do not see much from the outside, and the scale is quite low and domestic. It rains a lot in North Wales, and the question is how to handle that, both functionally and poetically. When it was a slate quarry, a reservoir was constructed up the hill to the east, to drive the waterwheel and turn the machinery. We were going to collect the rain as it fell on the roof of the building, channel it from level to level into the courtyard and from there away down into the old waterwheel pit. We found two geometries on the site (Figures 1.9.4 and 1.9.5). One was derived from the existing buildings, and the other from the general line of the old slate tip. The pivot between these two geometries, coupled with the way you rise from one level to the next, was the key point in the layout. When the circular lecture theatre came into its position as a hinge, it made a place around which you could bend these two geometries. Then there was the idea that the first courtyard should be very enclosed and private for the education spaces, whereas the

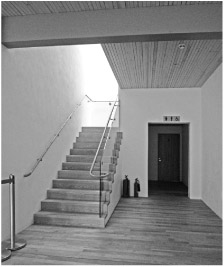

Figure 1.9.7 View across hall to top-lit wall and stair rising to next level

Source: Photograph by Tim Soar

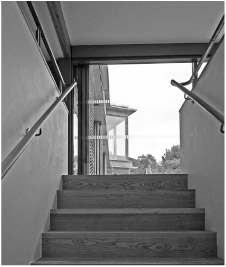

Figure 1.9.8 View through door at head of stair, courtyard to left

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

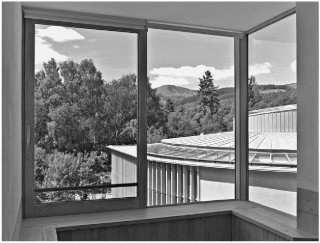

Figure 1.9.11 Approaching landing: view of terrace emerges

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

Figure 1.9.13 (far left) Corridor leads to seminar rooms

Source: Photograph by Tim Soar

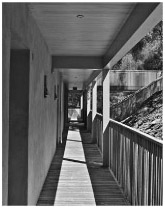

Figure 1.9.14 (left) Bedrooms approached by open gallery

Source: Photograph by Peter Blundell Jones

An early sketch shows how this might work (Figure 1.9.4). The dotted line represents the back wall of the first room you come to, removed to show the courtyard behind. You can see the movement up to the half-level, up again around the courtyard and then up the main stair to the next level, from which you can look out to the surrounding countryside. At first, we planned the twenty-four bedrooms on a different site, much steeper and with better solar access. They were to be stacked into very narrow terraces, along the contours. A shallow stair would rise to a common room at the entrance level, and then on up to the bedrooms. Each bedroom would have a generous corner window opening into the trees – each bedroom a treehouse. That scheme involved an additional common room and was too expensive, and so, eventually, we wrapped two floors of bedrooms around the courtyard of the teaching blocks. The dining hall and main entrance grow out of the existing restaurant. From there, the route leads up to the foyer, the distributor for the 200-seat, circular lecture theatre and the teaching spaces around the courtyard, and out to the south. Up on the next level, there are offices for the CAT staff and the first floor of twelve bedrooms, then up again are the seminar rooms and the second floor of bedrooms.

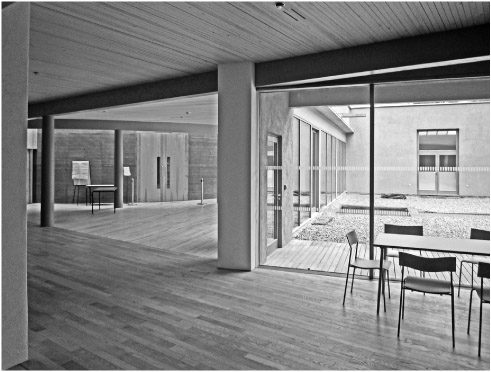

The journey through the building starts at the entrance court, which is contained on its north side by the restaurant extension. This can be opened out completely in the summer by the big glass doors being slid back. The visitor is welcomed immediately into a big, lively hall. There is a roof light along the back, so that the wall is lit even on a dull day and artificial light is seldom needed, and, when the sun comes out, the wall is illuminated by changing shafts of light (see Figure 1.9.7). The timber columns have entasis: a slight curving inwards towards the top, which makes them feel a little stronger and corrects the somewhat crude appearance of columns with parallel sides. This device has been used more or less wherever anyone has built columns, from China to ancient Greece. The bottom third is vertical, and the column curves in from there to a top diameter one-sixth smaller than the bottom. Those are Palladio’s rules, and they seem to work quite well. You can set it out with a thin and bendy wooden lath.

From the entrance, you get a glimpse of the courtyard above and the different levels; you do not see much, but enough to give you an idea of what is in store. A very shallow stair rises to the next level – a ‘float-up’ stair – the shallowest permitted by the building regulations. We wanted to express that by showing the steps, and that is why there is a glass balustrade. At the head of the stair is a door to the left, leading to the first courtyard (see Figure 1.9.8). You see the stair going up to the next level ahead of you, top lit, and then the courtyard to the left. In the courtyard, water from the roofs cascades from the gargoyles down into the pools and then flows into a slate-lined chasm, the remains of the old waterwheel pit. It is paved with gravel and slate. There are very few plants, just three trees and ferns. You can see the bedrooms up above. Reflections off the water cast constantly moving, rippling light on the walls and the ceiling, particularly in the afternoon. The three teaching spaces around the courtyard are also top lit and full of light. All of them can be opened to the courtyard, allowing teaching with the windows wide open. I often use toplight in my buildings.

Just as the courtyard lies to the left of the foyer space, so the drum of the rammed-earth lecture theatre lies to the right, and there is light coming down between the roof and the rammed earth. The wall was made in four separate sections, with gaps between for openings. The three rows of fixed benches are separated by 2 metres, to allow space for tables and chairs between them: the theatre can then be used for parties, gigs and wedding ceremonies, as well as lectures. The oculus in the ceiling, the main source of natural light in the space, can be closed by a big, circular shutter, the ‘moon-disc’, which pivots around and eclipses it. The CAT staff wanted a view and a way out into the gardens from the lecture theatre. They do not always use it, but it is nice to have the huge opening into the breakout space and the view of green beyond. The opening can be closed with a vast, curved, sliding door, slatted in the same way as the acoustic panels on the walls. Light from the other openings is controlled by angled slats, so that images on the screen are not overwhelmed. We wanted the projection screen to have a strong presence, like a kind of reredos at the back of an altar, and so we have alternating bands of dark green and white, with a very rich panel below, which has dark green slats against gold, and as you walk past the gold background is revealed.

Returning to the foyer, stairs at the end rise up to the light (see Figure 1.9.10) and emerge on to a terrace with a view into the treetops, contained on the north side by staff offices. A left turn at the top of the stairs reveals a close-up view on to the slate tip – spoil from the old quarry – as it cascades down behind the building, focusing attention on the small trees that have established a precarious foothold. The gallery to the bedrooms leads off this space, and it is nice to have to go outside to get there. It does not seem to be any hardship, and people at CAT are quite used to it, but you can imagine that, in some institutions, people would have that glazed in, and then the whole thing would become something different. It would also have to be heated, and so costs would start to rise. The bedrooms are entered through small lobbies that provide a sense of protection and privacy within the room. The rooms look out over terraces and courtyards to the view across the valley. The upper rooms have window seats about 600 mm wide, and the windows can slide right back, so that it is like being on a terrace. On the lower floor, windows are full height, opening on to a landscaped deck.

Returning to the head of the stair, a short corridor leads to the seminar rooms. The first two look east, with a close-up view of the slate tip. You don’t get much light off the slate, and so these rooms are mainly lit by a circular top light, which echoes the oculus in the main lecture theatre. As you emerge from these rooms, a little window allows a glimpse across the valley to the hills beyond. At the end of the corridor, a door opens into a larger, higher space. The facing wall is at a slight angle, and so the sun hits it before the rest of the room. Light is a magnet and draws you in. You do not see the window as you enter, only the light on the wall and the window seat going round into the opening. This window place is the culmination of the journey through the building (Figure 1.9.15). You can slide the window open and sit as if on a balcony, and from there you look back on the whole scheme and the mountains beyond.

Notes

1 Tzu 1963, p. 67 (although Lea cites another translation (ed.)).

2 See the very good article in Architectural Design, March 1966, by Günter Nitschke called ‘Ma: The Japanese sense of place’. ‘Ma’ suggests relationship, and so the relationship between you and me is the place, the space between us.