4.2

Movement and the Use of the Sequential Section by Enric Miralles and Mathur and Da Cunha

A section is a measured drawing, an orthographic projection from a line in plan on to a vertical plane. It is a static abstraction of a particular built condition, to be understood in relation to the plan. It shows spatial variation and relationships in level. For the architect Enric Miralles and the landscape architects Anu Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, the section further became a means of exploring the experiential qualities of space and its relationship to human inhabitation. They adhered to the conventions of measured orthographic sections, but redefined them through overlay and repetition to make them expressive of human movement.

Paper and site

Miralles practised in Barcelona from 1984 to the time of his death in 2000. He won several key competitions in the 1980s, which led to the formation of his first office with another Spanish architect, Carme Pinos. Several of his projects contributed to his high international profile, including his design for the Igualada cemetery and the Olympic archery range for the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona. He also taught at several design schools in Europe and the United States, including ETSAB in Barcelona and the Graduate School of Design at Harvard. Anu Mathur is professor and associate chair of the landscape architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and collaborates frequently with fellow professor, architect and planner Dilip da Cunha. Together, they research how the visualization of water might expand possibilities for design practice. The body of their work is presented in three main books, published between 2001 and 2009, on the Mississippi River, the Mumbai peninsula and the Deccan plateau.

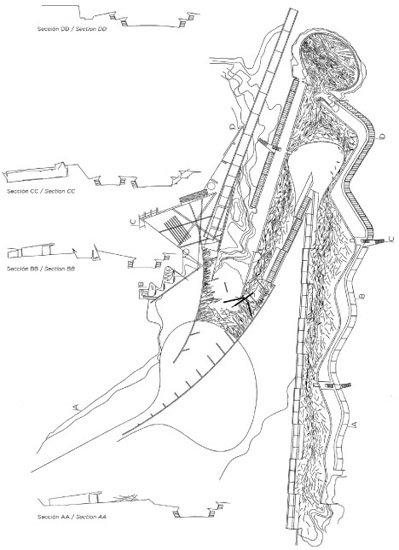

Both Miralles and Mathur and da Cunha perceived drawing and the space of paper as analogous to site. Miralles frequently equated the act of drawing a line to the act of construction. In an invited talk given during the Wednesday evening architectural lectures at SCI-Arc in 1989, Miralles noted, “the drawn line is anything else but, it is grasping, digging or moving the earth until finally a position deals with the topography.”1 He was describing the process of designing Igualada Cemetery, work he first commenced in response to a 1984 competition for a new cemetery in the Catalan town of Igualada, Spain: “This is how you

get to the space . . . it is trying to find with a pencil a place to put the dead.” The drawing of sections through the landscape of Igualada was for him a movement, a precise excavation that simultaneously shapes earth and experience.2

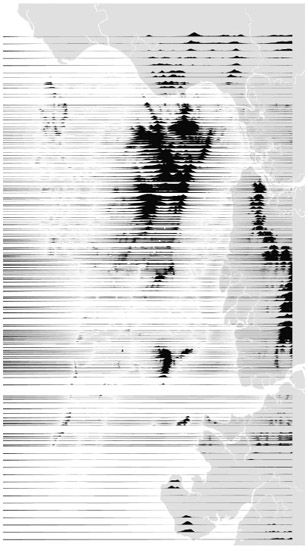

Mathur and da Cunha have equally suggested that the process of drawing is a process of constructing and reconstructing, particularly in relation to their work on the delta plain of Mumbai. In their book Soak, Mumbai in an Estuary, a detailed visual and textual examination of flood, drawing is no neutral technique. They are critically engaged in how and why one draws plans, sections and traditional maps, and what these drawings suggest about the comprehension of water and land. Mathur and da Cunha decry the insufficiencies of the master plan as a means of recording and responding to ecological processes and human movements. They note:

[The landscapes of Mumbai] call for the use of the section, an articulation that makes depth critical to the fluid relation between land and sea, while their drawing in sequence speaks to the diverse movement between the two. Sections also reduce the significance of boundaries and edges in the landscape, positing instead the horizon which one approaches but never crosses. They call attention to intersecting continuums rather than finite adjacencies. Finally, these landscapes diminish the importance of geographic space, the milieu within which surveyors measure distance accurately from point to point. Instead of space, they call for time, releasing landscapes from being held down to points in space and as such allowing the appreciation of their fluidity.3

Mathur and da Cunha argue that the representational devices of plans and surveys them -selves define a conceptual and imaginative position about water and its relationship to human inhabitation. A plan is concrete in its depiction of water as a channel-confined liquid. A section accommodates its depths: its flow from one kind of containment to another. A plan may enable the conception of a flood, which occupies the land beyond the river’s boundary, but the section enables a conception of water moving, of it falling, flowing and soaking.

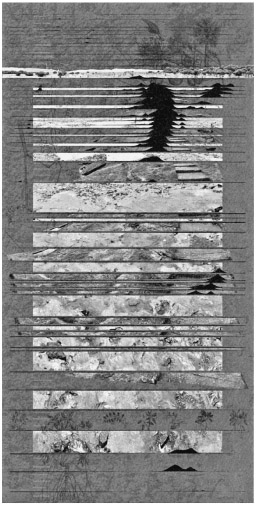

Mathur and da Cunha’s drawing of the Mumbai peninsula is an accumulation of sections that reconfigure the relationship between water and land. Instead of suggesting mutually exclusive regions of wet and dry, they create a graphic representation of the interpenetration of water and land, where the movement of water is no longer delineated by channel lines, but land instead becomes an open surface, a sponge through which water flows and collects. Their sectional precision shows the uncertainty, the ambiguity, of where the limits are. The black sectional mass in the Mumbai drawing delineates both water and land, with no graphic break between them: there is a refusal to give water a definite edge. The articulation of land and sea is absent and ambiguous, suggesting movement, and so, with their use of the repeated section, Mathur and da Cunha reframe the “hydrological imagination.” It marks a shift in drawing convention from the master plan that characterized colonial and contemporary urban development in India, initiated by Patrick Geddes, who lived in Mumbai.4

Repetition abstraction

Both Miralles and Mathur and da Cunha use the section to frame an immediate measure of width and breadth. And, through repetition, they begin to create depth. The sections can be read as individual moments along a trajectory, but also as a whole. The Mumbai sections

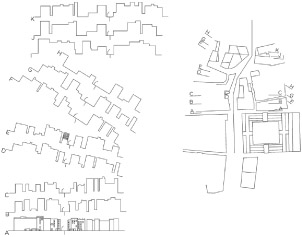

Miralles also systematically repeats sections at dense intervals throughout his projects. He maintains a clear relationship between the sectional drawings and plan and sometimes even rotates them, reflecting a human trajectory. We see this in the preliminary drawings for the Mercat de Santa Caterina, a refurbishment of a nineteenth-century market in Barcelona. Miralles traces a route in plan and then systematically cuts sections at even intervals along it and stacks them, delineating progression along the street.

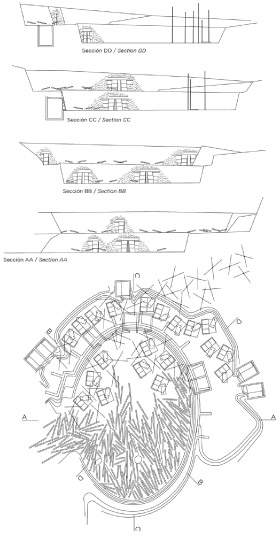

We see this again in the plans for Igualada Cemetery, where the sections appear adjacent to the cut lines along the main route, and in the drawings for chapel and mortuary, where sections are both stacked and rotated in relation to plan, so that the setting out on paper of the sections parallels how the spaces might be experienced through actual movement. The location of the sections on the paper seemingly reflects the directions of one’s gaze, which shifts and turns in response to a path through the cemetery.

Figure 4.2.3 Enric Miralles, EMBT: Mercat de Santa Caterina, 1996

Source: Redrawn from the original by James Simpson

Miralles’s engagement with human passage is evident in the commentary through which he explained Igualada Cemetery to his audience at SCI-Arc. He notes, “And then you go here to the chapel and it is like this, and then you take a car, and it’s like this and then you are here.”5 His narrative is sequential, and so are his drawings. He repeatedly reworks the standard section, repeating it and overlaying it on plan as if he is, through drawing, moving through the cemetery space. He maintains the conventional, measured relationship of section to plan and even emphasizes it. But, in repetition, he redefines it. Each section marks a shift in inhabitation. The drawings are abstract, and yet the commentary is intimately descriptive: he knows where mourners will descend from cars, how they will walk to the burial site, where the priest will stand. He considers ascent and descent and their relationship with trees. He notes that the siting of the cemetery and lines of his drawings are “an abstraction coming from the fact of walking, of walking and ending and beginning and ending at the river, etc.”6 Miralles is not interested in scenographic drawing: he repeatedly notes in his lecture that perspective sketches “are not the drawings we do to find form . . . this is just for the client.”7 Instead of proposing a drawing or imagining space from a single view, he uses the multiplicity of sections to convey different experiences of space, as hand, eye and body move through it.

Figure 4.2.4 Enric Miralles and Carme Pinos: Igualada Cemetery, mortuary, 1984

Source: Redrawn from the original by James Simpson

Many artists study movement through sequential repetition of a static image. Muybridge is perhaps most notable in his photographic studies of gait. In Duchamp’s Nude Descending A Staircase, the repeated overlay of a series of static figural studies conveys dynamic human movement. What is different in Miralles and Mathur da Cunha, however, is that they do not repeat a figure, nor indeed do they make any concession to a scaled figure. Rather, the landscape (building) itself is repeated, and a spatial experience is constructed out of the variations in section.

Miralles was concerned with movement through a site, but he also noted in his SCI-Arc talk, when speaking of a redesign for a town hall in Barcelona, “I hate this. To make people understand a building through a particular way of moving through it.” He goes on to say that he prefers simultaneity, like in a drawing of Picasso’s, where the face and the back appear at the same time.8 With the town hall, the shifting building profile expresses movement in the built structure. In a similar way, his sequential sections convey simultaneity and possibility as they depict individual spaces, but also their collective impact over space and time. There is an oscillation, an individual pause in space and time, and the accumulated awareness of all the different kinds of space moved through, that gives measure to the memory of one’s passage through space or territory. Miralles thus gives a thickness or depth to the conventional section that demonstrates his conceptual position toward the walker, the building and the site—to space, time and movement.

Ambiguity and overlay

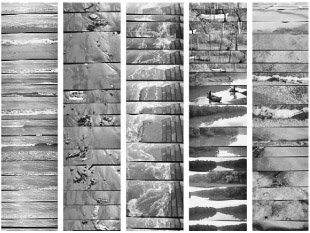

The wide range of representational techniques that distinguishes the work of Mathur and da Cunha demonstrates an equivalent interest in human movement across the landscape. They developed an image lexicon, itemizing particular visual methodologies. In the photosection, for example, repeated measured sections are layered with photographs systematically recording variations in wet and dry, rough and smooth or light and dark. In the terrain plot, archival plans and drawings are the ground for sequential sections that determine the rhythm and interval of detailed photographic strips of water, mud or dried clay.

The figure is absent in each kind of representation; there is no scale person placed against the background of the landscape. Rather, the drawings can be understood as being seen from the point of view of a person already immersed within the landscape: the observer of the drawing is as much a walker through the landscape as Mathur and da Cunha themselves. They add density to their sequential sections by splicing in photos or historical information. They combine measure with experience, juxtaposing an abstract measure with a tactile one. They reconstruct the ground of a territory in its experiential force. If Miralles required abstraction to explore topography, built form and movement, Mathur and da Cunha demand complexity.

The systematic recording of landscape along a trajectory and its organization in grids create a relational, exploratory field. The assemblage of many instants in time by Mathur and da Cunha creates a non-hierarchical view of the whole and makes their drawings, like the plans and section overlays of Miralles, expressive of simultaneity and ambiguity that seem to parallel the actual experience of moving over the site by foot and eye.

For Miralles, building and site blur at Igualada Cemetery. The ground is not something the building is on, but what it is shaped out of. The topographic cut of the route into the cemetery is shrouded under canopies of trees that make it continuous with the surrounding landscape. A place of procession becomes a place of sanctuary and stillness, and a route that descends a slope into the cemetery later also ascends through the height the trees provide.

Here, Miralles creates an ambiguous relationship between figure and ground, through the use of overlapping planes, floating horizontals, sloping walls and dynamic structures, whether in steel, wood or concrete embedded into or piercing through the space . . . relationships such as man–architecture, architecture–site, site–landscape and man–land -scape are forced to redefine themselves within this valley of the dead, in which the cemetery emulates the path of life, both spatially and temporally.9

Figure 4.2.6 Terrain plot, 2009

Source: Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha

The line Miralles defined by drawing/digging into the site yields a meander and multiplicities.

Miralles and Mathur and da Cunha have made conscious decisions to use the section. Their use of this drawing convention, more than written texts, is a means of establishing theoretical considerations that are relational, that see building and ground, or water and soil, as a continuum. In their circumstances, Miralles and Mathur and da Cunha are, of course, sub -stantially different. Miralles worked by competition or by commission to construct buildings. Mathur and da Cunha draw and research alternative approaches to landscape and process. However, their shared concern with simultaneity and multiplicity and similarity in deployment of representational techniques to explore space, movement and time are telling. For Miralles, sections express the relationship between thought and construction, and what he construed about movement through drawings was constructed. Mathur and da Cunha push the boundaries of landscape representation, taking the section as means of “rethinking the meas -ures and possibilities of design in Mumbai.”10 By isolating, abstracting and reassembling the sectional drawing, both managed to reconfigure the spatial experience of movement. The section became a means, not simply of analyzing a physical change in levels, but, through repetition, also a means to record a trajectory of time, experience and motion.

Notes

1 Enric Miralles (March 01, 1989) Enric Miralles. SCI-Arc Media Archive: Southern California Institute of Architecture. Available at: http://sma.sciarc.edu/video/enrique-miralles/

2 Ibid.

3 Mathur and Da Cunha 2009, p. 8.

4 Ibid., p. 8.

5 Enric Miralles (March 01, 1989) Enric Miralles. SCI-Arc Media Archive: Southern California Institute of Architecture. Available at: http://sma.sciarc.edu/video/enrique-miralles/

6 Enric Miralles (March 01, 1989) Enric Miralles. SCI-Arc Media Archive: Southern California Institute of Architecture. Available at: http://sma.sciarc.edu/video/enrique-miralles/

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Zabalbeascoa 1996, p. 24.

10 Mathur and Da Cunha 2009, p. 8.