7

ON WATER AND OTHER FLUIDS

A bloody account of urban circulation

Louise Pelletier

In 1628, English physician William Harvey (1578–1657) introduced one of the most celebrated contributions to physiology: the notion of the full circulation of blood in living beings. His treatise, On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals (De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis) gave an account of the double circulation of the blood and the motions of the heart.1 Combining observations, experiments, and measurements, Harvey looked at the heart not as a spiritual seat of the soul, but as a pump that could be analyzed in mechanical terms. Harvey argued that the pulsation of the arteries depends upon the contraction of the left ventricle, while the right ventricle propels the blood into the pulmonary artery. Blood is pumped around the body by the heart, and once it comes back, it is circulated in a closed system through the lungs before being returned to the main circuit.

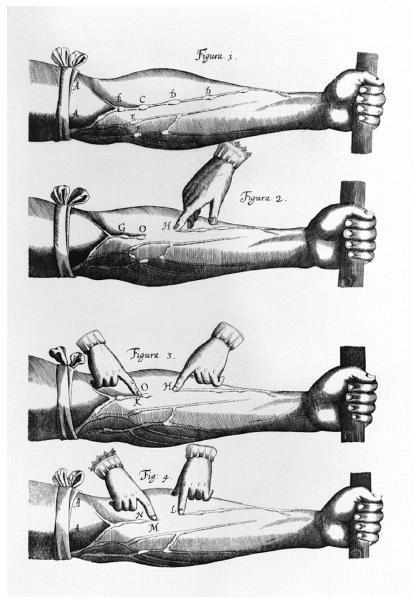

Harvey investigated among other things the effect of ligatures on blood flow and established that a tight tourniquet fasten on the triceps would interrupt blood flow from the arteries and the veins, causing the forearm to turn cool and pale from lack of blood, while above the ligature it becomes warm and swollen. By loosening the tourniquet slightly, blood flow is restored only from the arteries because they are deeper than the veins. Consequently, the opposite effect occurs in the lower part of the arm that becomes engorged with blood, turning warm and swollen. This experiment also made the veins more visible as they were distended with blood. By pushing on the veins down the arm, Harvey noticed that the flow was interrupted at various intervals by little bumps (identified by his teacher Hieronymus Fabricius as valves). But when he pushed upwards, the flow was not interrupted (Figure 7.1). He noticed the same effect in various veins of the body, except those of the neck where blood flows downwards – towards the heart – rather than upwards. Harvey concluded that valves allow blood to flow in one direction only – that is toward the heart.

Figure 7.1 William Harvey, De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis (1628), plate showing the effect of ligatures on blood flow

In H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness, Ivan Illich explains how Harvey’s discovery of blood circulation transformed our understanding of the human body, but it also influenced our perception of society and the city as living organisms. Around the middle of the eighteenth century, the notions of wealth and money were “spoken of as though they were liquids” and began to circulate. Social hierarchy came to be imagined in terms of connections as a system of conduits. “Liquidity is a dominant metaphor after the French revolution; ideas, newspaper, information, gossips and – after 1880 – traffic, air and power circulate.”2 If toward the end of the seventeenth century, the removal of fecal matter from the corridors of the Palace of Versailles and the streets of Paris was at best a weekly procedure, during the Enlightenment, cities became perceived as evil-smelling places that could no longer be tolerated.3 In fact, until the middle of the eighteenth century, it was common practice to throw bodily wastes into open spaces such as the Cemetery of the Innocents in Paris. The city gradually became understood as a body through which water ought to circulate without interruption in order to wash it from its impurity, its wastes. Thus, the circulation of air and water became an architectural concern long before the remodeling of Paris by Baron Haussmann in the nineteenth century.

Flowing beneath the pavement

Pierre Patte (1723–1814), a French architect under the reign of Louis XV, is credited for having been the first to design a modern sewer system for Paris to manage not only drinking water, but also rain and wastewater. Accordingly, he devoted an entire chapter of one of his treatises on what he calls “the corrupted distribution of cities” – “Considérations sur la distribution vicieuse des Villes,” in which he expresses the virtues of air and water circulation, but where he also speculates on the working of the guts of the city.4 His interest in the subterranean domain is made explicit from the very beginning, since the title page of his treatise dedicated to The Most Important Objects of Architecture depicts different monuments, ornaments and a public square, but most importantly, an arch on the bottom left of the image that leads to the underground, and incidentally, announces the first chapter of the book (Figure 7.2).

Patte began his reflections on circulation by acknowledging the role of tradition in first choosing the site of a city by referring to Vitruvius who recommended checking the liver of animals to see if they were healthy.5 Patte stresses the importance of knowing the composition of soil in order to determine its fertility, but also its propensity to earthquakes. Yet, he deplores that founders never seem to pay attention to these considerations, as they are more concerned with political reasons, taking possession of a strategic route; the confluent of two rivers; a strategic commercial position.6

Figure 7.2 Pierre Patte, Mémoires sur les objets les plus importants de l’architecture (1769), detail of the frontispiece

Patte asserts that never before has a city been laid out with the purpose of insuring “the well being of its inhabitants, of preserving their life, health, goods, and for insuring the safety of the air and their homes.”7 In any big city, what is most striking, he complains, is to see from all parts flowing excrements and wastes in open streams before continuing into the sewage system, and exhaling in its path all sorts of nauseous smells. Furthermore, the blood from slaughterhouses runs in the middle of the street; entire neighborhoods reek of waste from latrines; hospitals and cemeteries perpetuate epidemics and exhale the germs of sickness and death in the houses. Elsewhere, he says, one can notice that rivers that cross the cities and whose water serves to quench the thirst of its inhabitants are also receptacles of the cesspools and of all the refuse. When it rains, water washes off the roofs transforming the streets into rivers of mud. In short, cities are the embodiment of filthiness, infection and disease. Moreover, cities are often the prey of other calamities such as engulfing fires, floods and earthquakes. The purpose of his book, therefore, is to imagine how to take advantage of the elements, to control them for the benefit of men and to ensure the healthiness of cities and the happiness of its inhabitants.8

In order to attain such ideals, it is foremost important to ensure that cities be as compact as possible, and the trades and crafts that create smell and noise such as tanneries, tripe shops, blacksmiths, edge-tool makers, laundress, hostelry for public transportation, etc., should be placed beyond the edge of cities in suburbs. He advises that slaughterhouses as well as their stables also should be relegated to the outskirts of cities to prevent herds of cattle crossing the streets causing embarrassment for all.9 This is indeed the beginning of industrial urban sprawl. According to Patte, a twenty-five foot wide channel would surround the suburbs and would communicate with the river crossing the city at its entrance and exit so as to ensure air circulation. We should place hospitals and cemeteries beyond the suburbs on elevated and well-aired location to prevent the spread of diseases, he warns, and forbid the construction of houses on bridges as they are found in Paris, because they stop the flow of air on rivers that serve to clean the city. Ventilation and ease of circulation between different areas is set as a priority.10

The cleanliness of a city should be one of its principal ornaments, Patte argues. However, experience shows that it is never the case; no matter how much effort and money is invested, large cities continue to exhale bad smell coming from polluted water from various industries or trades, hospital, cemeteries, latrines, etc. Before solving the problem of how to purge cities from their harmful smells, however, it is necessary to understand the manner in which the transportation of water is administered; and only by combining water and sewage conduits can we expect to find a solution, he writes, again echoing the dual circulation system first introduced by Harvey.11

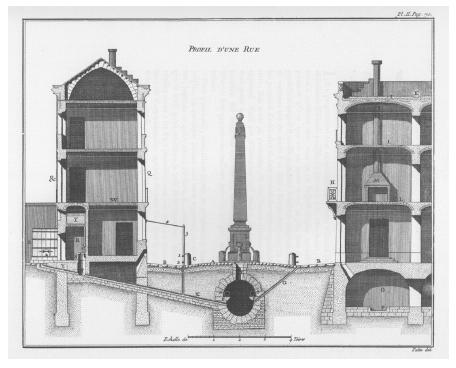

Patte analyzes different transportation systems made of lead pipes, wood and even clay conduits placed two feet below ground. Given their perpetual failure, he comes to the conclusion that the entire system has to be redesigned from scratch. He suggests an underground aqueduct six feet wide by seven feet high, placed five feet under street level. Two iron pipes located at four feet from the bottom of the aqueduct on little shelves of about fourteen inches would take the water from various reservoirs to the public fountains and houses without risking being crushed by horse carriages (Figure 7.3). That water would serve for everyday use, for bathing (an early mention of such domestic activity) or to drink. The system would also connect individual latrines to the cesspool and use rainwater to clean the system.12 Sewage would drain to the bottom of the cesspool into another aqueduct parallel to the river gathering sewage from all streets, itself draining into the river outside the city. As in a living organism where the oxygenated blood runs side by side with the vitiated blood, fresh water runs together with sewage in a complex system of fluid discharges.

Figure 7.3 Plate 2 from Patte’s Mémoires showing the appropriate distribution of a street

In addition to this circulation of water and waste, Patte insisted on the importance of air circulation for human health. He gives the example of a fan invented by Stephen Hales to renew the air of Newgate prison that improved noticeably the health of prisoners.13 Patte also criticizes the “relatively recent” tradition in Europe of burying the dead within city walls, or even inside churches as this custom was most harmful to the health of the inhabitants. Patte devised an inspired system to get rid of diseased bodies that was as ingenious as his dual aqueduct system. His invention involved a new ritual for burying the dead. The coffin would be placed in a chapel on the street side with an operable trapdoor opening on a vault beneath it that would allow for the removal of the body:

At a present time – like two in the morning – a cart pulled by horses, covered with a mortuary sheet, would come from the parish cemetery to remove the bodies from the crypt; the gravediggers with one lantern each and a priest in confidence who would be in charge of the cemetery would accompany the convoy. This priest would have a key to the exterior door of the crypt ….14

After removing the bodies, the priest would register them and would make sure that they be buried with the proper decorum in a cemetery outside the city walls, located approximately one mile from the city limits, in a well ventilated location. Walls of at least twenty feet would surround them: “in this way, vapors would rise into the atmosphere, and couldn’t infect the air.”15 To put Patte’s ideas in context, a law was passed in 1765 making cemeteries illegal inside the city, but it would take almost fifty years for remote cemeteries to be widely accepted. Even though the Cimetière du Père Lachaise was officially inaugurated in 1804, it is only after the remains of Héloïse and Abélard were transferred there, together with those of Molière and La Fontaine, that it began to enjoy some recognition.

In time, Patte speculates, families would build their funerary monuments that they would decorate with sculptures and medallions with portraits and obelisks, so that such places could very well become the most curious places in a city by the importance of their monuments and their works of art. In Patte’s view, it would be a great advantage not only from a health standpoint, but also in regard to social and religious issues. What is most interesting, however, is that the disposal of bodies – like that of excrement – would then become hidden from sight (removed in the middle of the night) in order to purify the air but also the unsightly activity. It signals a detachment – Illich might say a denial – of death.

A century later, Patte’s insight about the role of water and air circulation to ensure the health of a city would help transform Paris under the direction of Baron Haussmann. Circulation became synonymous not only with the health of an urban agglomeration, but in French it also refers to the flow of vehicles: traffic (circulation routière). It could be argued that the paradigm of health and circulation that came about between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and that led to the need to relegate some functions away from urban centers, transformed into an obsession with transportation (and a different approach to consumption) in the early twentieth century. Moreover, it brought about the plague of urban sprawl.16

Water as commodity

Today, one would imagine that we have mastered all issues regarding water circulation and related matter. Yet, according to the “Global Annual Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water,” a UN commissioned report, access to drinking water remains an important issue for many communities around the world as one billion individuals are said to be without access to any reliable source of drinking water and more than two and a half billion people cannot rely on a sanitation system.17 The problem, however, is rarely due to a lack of technological means. Water has become a commodity and, as such, its consumption has become an economic as much as a political issue. According to Transparency International, a non-governmental organization (NGO) that monitors political corruption in international development, in many countries, water has become the source of transboundary disputes and terrorism, corruption and political instability.18 Some communities rely on bottled water, which only compounds the problem with the environmental impact related to the accumulation of plastic garbage and other technological waste. Again, the problem of water circulation has been transformed into a problem of water transportation and consumption. But circulation as a concept may still offer some alternatives for improving the health of some communities.

Nowadays, circulation (as traffic) plays an important role in city planning. No longer restricted to the movement of air and water, urban planning is now primarily concerned with the movement of vehicles and people, and the commercial transport and exchange of goods.19 Thus, circulation is no longer synonymous with the happy flow of a balanced organism. In its association with traffic, it implies that what circulates (water) has become a commodity. In H2O, Illich argues that in contemporary cities, water has been devoid of its original sense of purity, “its mystical power to wash off spiritual blemish.” Water has been reduced to “the new stuff, on whose purification human survival now depends,” “a resource that is scarce and that calls for technical management,” a cleaning fluid “that has lost the ability to mirror the water of dreams.”20 As water became a commodity in the twentieth century, the city was reduced to circulation and stopped being a “place,” or at least devalued “places” – buildings can no longer occupy the old bridges, and the cities of the dead, which were necessary as the foundation for the cities of the living, were severed from the inhabited quarters. The issue then is to find a new way to create significant places in the complex network of circulation that has become the contemporary city. One example comes to mind.

Fluidity of information

In the city of Medellìn in Colombia, the development of a network of forty-six libraries in the city and the surroundings (known as the Red de Bibliotecas) and a complex system of public transit has radically transformed one of the most dangerous cities in the world, with an extremely high level of crime, into an urban development re-appropriated by the citizens. In the past decade, an enlightened municipal government provided the resources to develop a dual system of cable cars and metro lines that now links the slums that surround the city to the center, but most importantly, every cable system is connected to a new cultural center (at the heart of those communities) that includes primarily a library, meeting places, daycare and other facilities that create a sense of community.

Medellìn, the City of Eternal Spring – formerly known as “Murder Capital of the World” because of drug lord Pablo Escobar’s activities during the second half of the twentieth century, has a population of more than three million inhabitants (including the surrounding illegal settlements).21 The building boom that transformed the city since the turn of the millennium can be attributed in part to Mayors Sergio Fajardo (2003–2007) and Alonso Salazar (2008–2011). Convinced that architecture and urban design can initiate major social transformations, they launched a series of architectural competitions to develop cultural nodes in strategic locations in an attempt to revive civic responsibility and a sense of community. They invested all their efforts in restructuring the most desolate areas of the city to integrate them in the urban fabric. Combining infrastructure and innovative community programs, the municipal government intended to use architecture as a means to fight poverty. The general strategy involved direct interventions in the urban ghettos, called Las communas, in an attempt not only to cater to the basic needs of the population, but also to develop meaningful meeting places. It began with the construction of cable cars (Metrocables) to give easy access to the most remote areas. A trip that could take up to an hour and a half by foot now takes seven minutes with the Metrocable! Every station then became the anchoring point for public places and new housing developments; and finally, the construction of a library and community services accessible to all.

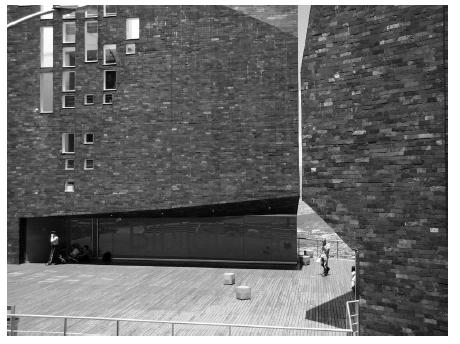

Two of the most discussed projects were developed by Colombian architect, Giancarlo Mazzanti, who won the public competitions in 2005 for the libraries in La Ladera, and the Parque Biblioteca España, in Santo Domingo Savio barrio – one of the most violent areas of Latin America.22 Built in 2007, the 5,500 square meter program is divided in three volumes that evoke three huge rocks roughly cut (Figure 7.4). Each is occupied by specific functions: a cultural center with an auditorium, a library with reading rooms (Figure 7.5), and a training center with classrooms. It also includes a daycare center. Although it has been criticized for its architectural detailing and the bluntness of its architectonic massing, the Biblioteca España is probably the project that had the most direct impact on social change. Through training and education, the project intends to provide new opportunities to the population and help them fight poverty, one of the primary causes of violence and social injustice.

Figure 7.4 Parque Biblioteca España by Colombian architect, Giancarlo Mazzanti in Medellín Colombia, view from a cable car (photo by author)

Figure 7.5 Library of the Parque Biblioteca España (photo by author)

In addition to the decrease in crime rate, the number of jobs has increased by 300 percent in the Barrio San Domingo and three banks have opened along the Metrocable route that leads to the cable car (Linea K).23 Children offer architectural tours of their barrio to tourists getting off the gondolas, thus confirming the sense of pride created by the project. To this day, five library-parks have been developed: La Ladera, Belén, La Quintana, Santo Domingo and San Javier.24 They have become symbols of urban and social transformations in Medellìn, contributing to the integration and participation of the entire population.

In his Mémoires dedicated to the most important objects of architecture, Pierre Patte had insisted on the importance of clean water and devised a complex system of distribution toward public fountains and public squares to help maintain the health not only of the inhabitants, but of the city itself as a live organism. It could be argued that like the water fountains of the Ancien Régime that provided vital infrastructure to sustain the life of entire communities, the democratization of knowledge and education in the library-parks of Medellìn, through their common ethical concern for the public good, have had a regenerative role on the community.

Notes

1 William Harvey, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Frankfurt: Guilielmi Fitzeri, 1628). Blood circulation was first described by Ibn al-Nafis in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna’s Canon (1242).

2 Ivan Illich, H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness (Berkeley: Heydays Books, 1985), 43–44.

3 Ibid., 46.

4 Pierre Patte, “Considérations sur la distribution vicieuse des Villes, & sur les moyens de rectifier les inconvéniens auxquels elles sont sujettes,” in Mémoires sur les objects les plus importants de l’architecture (Paris: Chez Rozet, 1769).

5 Vitruvius, De architectura, Book 1, chapter 4.

6 Patte, Mémoires, 5.

7 Ibid., 5.

8 Ibid., 5–7.

9 Ibid., 9.

10 Ibid., 10–13.

11 Ibid., 28.

12 Ibid. In plate 1, P indicates a latrine connected to the main system O; in plate 2, S is the seat, T is the pit and X, the pipe leading to the aqueduct; V is a small reservoir above the latrine which can be filled with rainwater from the roof; Y provides additional water from the courtyard.

13 Ibid., 38–39. This concern with the health of prisoners is somewhat paradoxical since Newgate was the largest short-term criminal prison in London that housed most of the highwaymen before execution at the Tyburn gallows.

14 Ibid., 43.

15 Ibid., 43–45. Ten years after the publication of his treatise, the Cimetière de Innocents closed in Paris, according to the law of 1765 that made cemeteries illegal inside the city. However, only after the decree of June 1804 that prohibited interment within city perimeters did the practice of suburban cemeteries become more widely spread.

16 This could be the subject of another article, or better yet, of another book – and Carolyn Steel addressed the issue in a masterful way in her own book, Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (London: Vantage Books, 2008).

17 “Global Annual Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS),” World Health Organization, accessed January 6, 2014, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241597166_eng.pdf.

18 “Transparency International,” accessed January 6, 2014, www.transparency.org.

19 The word traffic in English comes from c.1500, and meant “trade, commerce,” from the French trafique (mid-fifteenth century), which in turn came from the Italian traffico (early fourteenth century), from trafficare “carry on trade.” “Klein suggests ultimate derivation of the Italian word from Arabic tafriq ‘distribution,’ meaning ‘people and vehicles coming and going’ first recorded 1825. The verb is from the 1540s (and preserves the original commercial sense).” In comparison, circulation comes from the Latin “circulationem (nom. circulatio), noun of action from pp. stem of circulare ‘to form a circle,’ from circulus ‘small ring.’ Used of blood first by William Harvey, 1620s.” Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed March 11, 2012, www.etymonline.com.

20 Illich, H2O, 75–76.

21 The capital of drug trafficking in the early 1990s, the crime rate for violent crimes was over 25,000/year. Pablo Escobar was killed in 1993.

22 Estimated at about four million dollars, part of the construction was financed by Spain.

23 “The Gondola Project,” accessed February 20, 2012, www.gondolaproject.com.

24 Conceived in 2007 by Javier Vera.