Reflections on a Wind-Catcher: Climate and Cultural Identity

THE WIND-CATCHER (PART 1)

The wind-catcher is part of a natural ventilation system found in certain hot dry climate zones. It is a raised building element either facing in all directions, or facing the prevailing wind, in order to ‘catch’ it, bring it down into the building, and cool it with moisture from fountains, pools and salsabils (carved stone surfaces over which water runs). Once re-warmed by people and their activities, the air rises through a central tower and is pulled out of the top of the building by the same breeze that drove it inside in the first place. If there is no breeze available, wetted hemp mats can be placed over the openings of the wind-catchers. This moistens and cools the air as it enters. The cooling makes the air drop downwards, creating its own breeze. The wind-catcher is thus a very sophisticated piece of low technology and a characteristic element of an architectural style that seamlessly and elegantly combines performance and form, climate and cultural identity: traditional Islamic architecture. In a contemporary context, however, are the same means of preserving and perpetuating architectural identity available to the Gulf States, or to any other region where traditional built culture is colliding with the hegemony of a high and universal technology?

17.1 A typical traditional wind-catcher in Iran

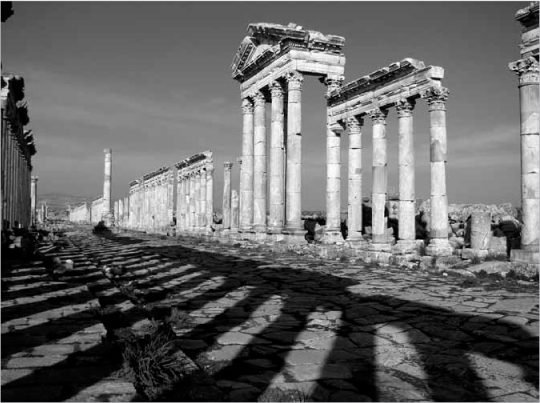

17.2 Roman classical remains in Syria

Architecture has been debating identity ever since the ‘International Style’ hove into view, although of course it was hardly the first international style. Roman classicism reached right across its empire. Islamic architecture spread all the way to the Far East. The connection between built culture and so-called ‘globalisation’ is not one of style, but of western industrial technology, western financial might and western expertise imposing itself on the rest of the world. Globalisation goes deep economically but, I’d suggest, is only a veneer politically and culturally. The high-rise block housing for an Islamic family and that housing a Christian one neither helps nor hinders their very different ways of life. Human beings are far too entrenched in their ways, and far too adaptable, to allow one stage-set or another to interfere with their habits and traditions – up to a point, at least. The location of that point is the real question. When does the built environment impede the living out of a culture? And which culture are we talking about? Is it the culture of the past, or an emergent culture grappling with enormous external forces? The cities of the southern Gulf have grown so quickly in a few decades, they couldn’t possibly have produced a perfect synthesis of disrupted traditions and disrupting economics and technology in that time. The question is where do they go from here?

Once one slows the alarmed gaze, difference proliferates everywhere, and globalisation is seen to be pervasive but limited. There is, for example, an enormous difference between poor developing countries and rich ones. Poor developing countries find it very hard to resist western economic penetration. Rich developing countries have more control over what they do and don’t let in. The wealthy countries of the southern Persian Gulf region certainly fall into the second category, although in the realm of the built environment, western industrial technology has obliterated traditional material culture, even if it has to be said that it has done it more totally at home than anywhere else. We have, though, been here before. The discussion going on now in the Gulf States was going on in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s in the developed and the developing worlds. Then, the architectural reaction to a universalising industrial technology, so-called ‘post-modernism’, was as heartfelt as it was ineffective. The first call to arms was historicist post-modernism, with its desire to ‘enrich’ architectural modernism with architectural history. It ranged from the mildly necrophiliac (for example, Phillip Johnson’s AT&T Building in Manhattan in 1979) to the entirely necrophiliac (for example, Quinlan Terry’s Richmond Riverside development in London in 1987), from pastiche to exact imitation, primarily of classical architecture. The second revolt was called ‘Deconstruction’, aka ‘Deconstructivism’, originally a philosophical assault on the construction of meaning in language, translated over-literally into architecture by Peter Eisenman, Coop Himmelblau and others. Both rebellions against architectural modernism operated entirely within modernism’s dominant technologies and industrial ways of making, and did nothing to redirect its energies.

THE FIRST WAY: DEEP RETURN

At the same time, however, there was a much deeper resistance that would have dented a universalising technology and the global economic system that supports it, had it been able to compete economically. In Vandana Shiva’s book, Monocultures of the Mind, there is a strong connection made between biological and cultural monocultures, and between biological and cultural diversity:

Diverse ecosystems give rise to diverse life forms, and to diverse cultures.

The co-evolution of cultures, of life forms and habitats has conserved the biological diversity on this planet. Cultural diversity and biological diversity go hand in hand.1

For Shiva, ways of making and living arise from particular ecosystems and their particular climates and materials. Hence the existence of traditional vernacular architecture: a human adaptation to a particular ecology, which functions as part of that ecology. A deep return of this kind, with different ways of life contingent upon different physical habitats, therefore requires a return to vernacular craft economies, and in the 1960s and 1970s, just such a return was called for. In the developed world, it informed what the Luxembourg architects, Leon and Robert Krier, called ‘rational architecture’ – a name chosen in a deliberate challenge to the rationalism of architectural modernism. In the developing world, the work and writings of the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy appeared even earlier, in the 1960s. What united these two positions was both valid and unrealistic. If the style wars of architectural post-modernism were a superficial return to a lost past of visual identity, Fathy and the Kriers’ work was a return to ways of making and ways of organising space. The deeper the return desired, however, the more elusive it is.

17.3 Traditional sun-dried bricks in Egypt

Fathy’s intention was to recover, not just an aesthetic, but an entire way of life – the life before Egypt began to modernise under Abdel Nasser, when it lost much of its building craft culture and the identity it provided. The symbol of cultural recovery was, for Fathy, sun-dried brick construction, used in Egypt since the pharaohs, and until the advent of breeze blocks in the 1950s, the basis of every village in the land. The arches, domes and vaults natural to such a material gave rise to an architecture suited to, and characteristic of, its locality, but Fathy was forced to train up builders in the old techniques because there were so few traditional craftsmen left, and the majority of his countrymen weren’t with him. The Krier brothers, like Ruskin before them, also condemned the industrialisation of building technology as alienating and unhealthy for its workers, and destructive of the centuries-old fabric of European cities. It was, however, too late to go back, even with patronage of a nostalgic member of the British royal family.

Resistance had, for Fathy and the Kriers, another weapon in its armoury: typology. Almost forgotten now is the amount of heat and light generated in the 1970s by the revival of interest in historical building and urban typologies – the traditional urban grammar that made up the distinctive languages of cities worldwide, which architects like Leon Krier reproduced, much as so-called ‘New Urbanism’ reproduces them now.

Against the anti-historicism of the modern movement we re-propose the study of the history of the city … The history of architectural and urban culture is seen as the history of types. Types of settlement, types of spaces, types of buildings, types of construction … The roots of a new rationalist culture are to be found here, as much as in L.N. Durand’s Typology of Institutional Monuments.2

Most violently rejected was the Modern Movement’s reversal of the relation between solid and void, the erasure of a continuous urban fabric and its replacement by free-standing objects. This rupture was, and is, particularly violent in the Middle East, between a climatically protective urban fabric, and the sizzling open spaces of ‘modern’ development, which requires unsustainable quantities of air conditioning to achieve acceptable levels of interior comfort, and makes the external spaces hotter than the desert.

Fathy was also at pains to recover not only lost building crafts, but also disappearing urban typologies. The climatically unwise over-scaling and/or gridding of the urban fabric had begun in colonial interventions in the Middle East during the 19th century, and were continued by indigenous rulers in the 20th century (and now in the 21st century), in a desire to modernise and be seen to be modernising. Today’s nostrums for ‘the sustainable city’ are nothing but a rehash of this traditional human-centered life that Fathy, the Kriers and others were demanding in the 1970s, now repackaged as energy-saving because this fabric has mixed uses and more density, and is therefore walkable.

THE SECOND WAY: CRITICAL INTEGRATION

In spite of the relevance of much of the critique that both Fathy and Krier made of the depredations of mid-20th century architecture and urbanism, the rejection of industrialisation within a built context was doomed. The developing world hadn’t fully attained an industrialisation to repudiate, and wasn’t about to deny it for themselves simply because the west had already experienced the full force of its disruption. The west was also enjoying the full force of an accompanying rise in living standards. And so, in the developed and developing worlds alike, a more complex position of both/and evolved, with varying degrees of success. This is the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur speaking from the developed world:

There is the paradox: how to become modern and return to sources; how to revive an old dormant civilisation and take part in universal civilisation.3

And from inside the region facing this paradox, this is the Iraqi architect, Rifat Chadirji:

There is no alternative but to bring the cultural development of Iraq into harmony with this process of internationalisation, while at the same time maintaining the nation’s traditional characteristics and qualities.4

The question was, and still is, which traditional characteristics and qualities? Not traditional building technology, which did so much to determine traditional visual identity. Chadirji himself is the epitome of an exchange of equals between a dominant internationalised culture and his own culture, drawing on the long history of Iraqi architecture and on western modern art and architecture to construct a synthesis. In his book, Concepts and Influences: Towards a regionalised international architecture, published in 1986, this rapprochement is presented again and again – with, for example, Corbusier’s Ronchamp and a traditional Baghdadi house feeding into his design for an administration building for Baghdad’s city government.

In abstracting and deploying traditional elements, Chadirji is also deploying traditional means of mediating between climate and interior. The environmental advantages of a climatically differentiated building envelope are energy-efficient as well as culturally grounded – the thick walls and green and watered courtyards effectively modifying microclimate. Chadirji achieves what Kenneth Frampton explicitly argued for in his writings on the developed world’s equivalent at the time: a ‘Critical Regionalism’. There were many versions of the culturally inflected modernism of ‘Critical Regionalism’, from the cultural specificity of Carlo Scarpa to the abstraction of Tadao Ando, but the most relevant for this discussion are those architects who focussed more on the relation of the building to physical site than to historical context, based on the assumption that the two are bound up in a dialectical relation anyway. Kenneth Frampton, the best-known theorist and promoter of ‘Critical Regionalism’, was explicit, and opened up the way for climate to return as an expression of culture:

Critical Regionalism is regional to the degree that it invariably stresses certain site-specific factors, ranging from topography … to the varying play of local light across the structure … An articulate response to climatic conditions is a necessary corollary to this. Hence, Critical Regionalism is opposed to the tendency of ‘universal civilization’ to optimize the use of air-conditioning etc. It tends to treat all openings as delicate transitional zones with a capacity to respond to the specific conditions imposed by the site, the climate and the light.5

This in turn is but a modulated echo of Hassan Fathy, who says:

… if you take the solutions to climatology of the past, such as the wind-catcher … and the marble salsabil with carvings of waves on them for the water to trickle over … you will find that they create culture. With today’s air-conditioning, you have removed that culture completely.6

In the view of ‘Critical Regionalism’, air-conditioning should not be ‘optimised’. For Fathy’s deep return, it should be abandoned altogether, because in losing a place-specific response to climate, you lose a source of differentiation in the built environment.

THE THIRD WAY: CLIMATE AND IDENTITY

The mashrabiya has a practical function as a sun-screen in front of an opening that expanded to include a cultural role as well, hiding the women of a Muslim family from public view, while allowing them to see out. The devices of modern technology have long since snapped any such connection between climatic and cultural function. Air-conditioners are not tied to any one set of tectonics, or to any one culture. But we’re no longer at the beginning of this trajectory. There have always been architects in the developing world – and within the Modern Movement itself – demanding a synthesis of the regional and the universal, and now there are more. Even more importantly, now clients in developing countries are beginning to demand the same.

To give an example, the Msheireb (formerly called the ‘Heart of Doha’), a 35-hectare development in the centre of Doha designed by Allies and Morrison, Arup, EDAW/AECOM and others, is to be part of what Sheikha Mozah of Qatar describes as ‘a rising homeland that confidently embraces modernisation and proudly observes tradition’.7 A responsiveness to climate is part of this observation of tradition, and the ‘Heart of Doha’ masterplan reproduces the dense, tight, self-shading knit of historic Arab cities and towns – albeit with much higher buildings. In several planned large-scale new developments in the Middle East, one sees some form of obeisance to traditional urban solid-void relationships and their traditional climate-adaptive morphologies. The fact that the resulting savings in fossil fuel energy are more often than not paid for with oil revenues is an irony that has yet to work itself out, as is the fact that this return to traditional typology is being achieved with a large contribution from western designers and engineers.

THE WIND-CATCHER (PART 2)

Bioclimatic design in developed countries is effecting its own resistance to the hegemony of high technology, for predominantly environmental reasons rather than cultural ones. Regardless of whether or not one considers global warming to be a conspiracy to undermine Ferrari, the rate of extraction from, and pollution of, a hapless planet overrun by a species that seems rapacious to the point of suicide, means these environmental reasons are now as important as the older cultural ones – especially if you view the cultural and the environmental as bound up with one another. An elegant efficiency of construction and operation is now de rigueur at the scale of building and city. In environmental design, this is achieved by any means necessary – whether by active strategies (mechanical and/or digital), or by passive strategies (which use the building fabric to mediate between inside and outside) or by hybrid strategies (mixtures of both active and passive means). Because the building envelope is now often returned to its original protective function, performing some of the work it did before the advent of mechanical engineering, its materiality becomes intensely important again in terms of reducing energy consumption. On so doing, it can then also inflect a contemporary building towards its cultural, as well as its climatic, region.

Traditional vernacular architecture is a treasury of techniques and ideas that are shamelessly borrowed by bio-climatic architects everywhere, so that there is now some exchange: western high technology streaming into the developing world, and low-energy techniques sliding back into the developed one. The reproduction of traditional styles is not involved in this borrowing, but the influence of tradition is pervasive. The circle of fresh air in/stale air out, driven by the buoyancy of hot air – the so-called ‘stack effect’ – can be seen reproduced in different ways in much bio-climatically designed architecture in the west. In not only undemanding domestic buildings, but in larger public and commercial buildings with complex programmes, one can see the use traditional, stack-driven passive ventilation techniques. This contemporary air isn’t usually entering through wind-catchers; instead it tends to come at the cooler ground level, and is then expelled through atria or special chimneys.

17.4 Torrent Research Laboratories in Ahmedabad, India, by Brian Ford and Associates (1997)

17.5 Plan of Torrent Laboratories showing the PDEC ventilation system

Such techniques have become new bioclimatic typologies in the west, but they are even more applicable to the climates where they originated – within a context of contemporary architecture. In hot humid climates like Malaysia’s, for example, where Ken Yeang has developed what he calls ‘bioclimatic skyscrapers’, these are protected from solar radiation by a series of layers, some built, some grown.8 Closer to the traditional model are Brian Ford’s low-energy cooling designs for the Torrent Research Laboratories in India, completed in the late-1990s. Here, the means of circulating fresh air are virtually identical to the vernacular techniques, but the wetted mats used to cool the air and make it drop on windless days in the traditional system have been replaced by micro-ionisers, which spray the hot air as it enters at roof level. As the sprayed air cools and falls, it pushes down and into the floors below, cooling them in turn. As it is warmed again, the air rises and evacuates through vents. Out of the wind-catcher and the salsabil has come Passive Downdraft Evaporative Cooling (PDEC), which can be used at an urban scale as well. The ‘cooling towers’ in some of the open spaces of the 1992 Seville Expo used the PDEC system.

The borrowing of vernacular environmental techniques, therefore, does not mean the borrowing of vernacular styles, unless the architect and/or client are after such an imitation. The architectural language used in most bioclimatic architecture is entirely contemporary, and most of the materials are industrially manufactured. Environmental design is not an answer to a perceived loss of cultural identity or to totalising modes of production, unless it is deliberately pushed in that direction. Climatic regions are not the same as political or cultural ones. An adobe building could be sitting in the hot dry American south-west or hot dry Syria. On the other hand, if Chadirji is right, then bioclimatic design goes some way to achieving his conciliatory objectives:

17.6 Seville Expo (1992), external areas installed with ‘cooling towers’

17.7 Rapid urban development under construction in Dubai, UAE

No truly excellent regional architecture can be achieved unless in some sense it blossoms from within its own culture. Iraq must therefore possess its own regional technology before it can have its own [contemporary] architecture.9

In building terms, the Gulf States do possess their own regional technology – a traditional, sophisticated low technology – and bio-climatic design is one way of enabling architects to integrate this with a universal high technology. At urban scale, bio-climatic design is also a way of integrating traditional morphologies that were also, among other things, clever responses to climate.

There has been a tendency in architectural discussion to present the part for the whole – for example, the extreme modernist development of Dubai as being representative of the entire and varied Gulf region – whereas something like Foster and Partners’ design for the new eco-city of Masdar, on the edge of Abu Dhabi, indicates a culturally and climatically more sophisticated synthesis of old and new on the part of architect and client (see Plate 27). If built fabric emerges out of established cultural identity, and that established cultural identity is changing, then the built fabric will inevitably change as well. The challenge, surely, is not to resist that change, but to direct it past the crudities of modernist zoning and ‘my skyscraper’s weirder than yours’, past climatic ignorance and democratic deficits. Modernity is emancipatory as well as disruptive. There is nothing to lament in a rise in living standards and an increase in opportunity, as long as everyone and everything (i.e. the environment) can benefit. This is a question of governance, not architecture. Architects can – and indeed should – propose, but governments and clients dispose. There is an emerging desire in the Gulf region to import the new ways of thinking and doing being developed in the west, not those being discarded by the west. If this shift continues to gain ground, then climate can provide a more regionally grounded means of negotiating between an unrecoverable past and new imports.

17.8 Masdar City eco-town on the edge of Abu Dhabi, UAE, by Foster + Partners

NOTES

1 Vandana Shiva, Monocultures of the Mind (London: Zed Books, 1993), p. 65.

2 Leon Krier, Rational Architecture (Gand, Belgium: Archives d’Architecture Moderne/Snoek-Ducaju & Zoon, 1978), p. 41.

3 Paul Ricoeur, History and Truth (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1965), pp. 276–277.

4 Rifat Chadirji, Concepts and Influences: Towards a Regionalised International Architecture (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986), p. 41.

5 Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), p. 327.

6 Hassan Fathy, Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1986), p. 15.

7 ‘CEO message’, Dohaland/Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development website, http://www.dohaland.com/company/ceo-message (accessed 29 August 2010).

8 Ken Yeang, The Skyscraper Bioclimatically Considered (London: Academy Group, 1996).

9 Chadirji, Concepts and Influences, p. 43.