Redefining the limits of architectural judgment

Introduction

In this chapter we argue that architectural judgment is best understood and practiced as a public conversation through which we shape our material, social, and ecological conditions. We also hold that the qualitative and quantitative assessment tools of conventional architectural judgment have generally failed to stimulate the public conversations required to cultivate the collective knowledge, capacity, and will of stakeholders to create conditions that sustain life. We define “life” liberally, evoking the concept of “living systems,” which includes every living organism, every part of those living organisms, and communities of living organisms that include humans and non-humans (Capra 2005). Because both qualitative and quantitative assessment methods may provide reliable feedback about the health of living systems, and are essential for sustainable management of the built environment, we raise concerns about dominant modes of assessment. First, traditional qualitative assessment is too often limited to elite modes of judgment, or the exercise of “taste” (Bourdieu 1984), where architecture is understood as either private sentient experience or public representation of social values. Second, quantitative assessment is too often limited to professional modes of judgment, where architecture is understood primarily in the economic terms of efficiency. Although these modes of judgment retain some value, by limiting the capacity to judge the built environment to social elites on the one hand, or professional elites on the other, the act of judging architecture never becomes relevant to the 96% of the population who inhabit and commission it. Without such a highly relevant and highly public conversation, we can never construct a sustainable “building culture,” or “the coordinated system of knowledge, rules, and procedures that … sustain life” (Davis 2006; see also Baus and Schramm’s discussion of “Baukultur” in Chapter 10 of this volume and their emphasis on the importance of incorporating the knowledge of experts and laypersons inhabiting buildings in architectural judgment).

Given these observations about the limits of conventional public conversation about the built environment, we maintain that architectural judgment has a responsibility to advance regenerative design – broadly defined as design that goes beyond simply reducing negative ecological and social impacts by actually generating benefits and creating material, social, and ecological conditions in which life can flourish (see Figure 24.1). If architects are to meet this challenge, they will need to participate in, and lead public conversations to catalyze, regenerative places. These public conversations will necessarily integrate more inclusive forms of qualitative and quantitative assessment into a regenerative dialogue where stakeholders can make sense of the rich complexity of particular places, imagine a life-enhancing future, and enact systemic change. In what follows we outline four characteristics of public conversation essential to the success of regenerative design and identify capacities required of facilitators and participants in these conversations. We then demonstrate that such regenerative dialogue is, indeed, possible, drawing from research in various social sciences and examples from regenerative design practice.

FIGURE 24.1 The Interrelated Concepts of Regenerative Design. From Beyond LEED, exhibition at the University of Texas at Austin, Fall 2012.

Source: Elizabeth Walsh, designer, produced through http://www.wordle.net

Precepts

We are not the first to claim that architectural judgment should be an inclusive public conversation about how the design of our built environment might better address the world’s most pressing problems. Aaron Davis and Thomas Fisher make similar arguments in Chapters 2 and 7, and provide examples from history. Nor are we the first to take note of the destructive effects that dominant practices of urban design and development have had on the natural environment and many social communities. While scholars and activists have been documenting these environmental and equity concerns since at least the rise of the industrial city, Lewis Mumford brought them to the center of architectural criticism starting in the 1930s. In his 1938 The Culture of Cities, Mumford offered a powerful call to action:

We must alter the parasitic and predatory modes of life that now play so large a part, and we must create region by region, continent by continent, an effective symbiosis or a co-operative living together. The problem is to coordinate, on the basis of more essential human values than the will-to-power and the will-to-profits, a host of social functions and processes that we have hitherto misused in the building of cities and polities, or of which we have never rationally taken advantage.

The challenge is as salient in 2014 as it was in 1938. In a world mired by escalating climate change, dwelling disparities, and public health threats related to the built environment, it is more important than ever to develop forms of architectural judgment that can help harness a collective will capable of catalyzing such a “symbiosis” of diverse social and ecological systems. In this chapter, we also offer propositions from the emerging scholarship and practice of regenerative design as partial answers to these core challenges for architectural judgment, drawing primarily from three recent inquiries:

1 The Beyond LEED symposium, which convened 13 recognized sustainable design leaders for a dialogue on the future of architectural judgment at the University of Texas in January 2012 (Moore and Walsh 2012).

2 “Regenerative Design and Development,” a special issue of Building Research & Information including nine articles by leaders in the emerging regenerative design movement (Cole 2012a).

3 Questioning Architectural Judgment: The Problem of Codes in the United States, which subverts the apparent conflict between art and technology in architectural judgment by observing that both sets of criteria are socially constructed and therefore mutable (Moore and Wilson 2013).

We see promise for the future of regenerative design in architectural judgment, yet we also observe significant challenges.

Where we are: the crisis of architectural judgment

Our research identifies two primary obstacles to achieving regenerative design within conventional architectural discourse: it is both too exclusive, and too narrow. We will examine each claim in order.

First, we hold that the discourse of architectural judgment is far too exclusive. We live in a world where professional architects design only about 5 percent of the built environment (Box 2007), with the rest largely dictated by market forces moderated by mandated public policies (e.g. building and land use codes) and voluntary standards (e.g. most green building rating systems), a concern also emphasized by Baus and Schramm in Chapter 10. If we want our built environment to achieve sustainable outcomes, architects will need to use the power of public conversation to catalyze social learning and social movements that shift consumer preferences, establish public codes, and generate new practices that reflect core human values, such as the will to protect life in its full diversity (Moore and Wilson 2013).

Second, we hold that the discourse of architectural judgment is too narrow. It too frequently fails to consider the related concepts of place, consequence, and complexity. Similarly, it errs in viewing building users as passive consumers of the built environment instead of influential inhabitants (Cole 2012c). Far from being a static, isolated artifact that can be judged “good” or “bad” in the eye of its beholder, a building is a complex aesthetic, social, ecological, and technological system that changes over the course of time with its inhabitants and context (Moore and Walsh 2012). Buildings are not simply isolated works of art, they are built to perform, and to assist their inhabitants in achieving particular goals. It is not enough to judge a building in the design phase, nor immediately following the construction phase because significant consequences of the building happen only after the building is inhabited. By drawing from the literature and methods of the natural and social sciences, design teams, including architects, might learn to judge not only the visual consequences of their work, but also the environmental and social consequences. (See also Nussaume’s argument in Chapter 9 of this volume that architectural judgment should include social science methods and consideration of social and ecological contexts.)

The bad news is that these limitations of architectural judgment are deeply entrenched. Moore and Wilson observe that when Vitruvius recorded and codified the elements of ancient architecture, about 15 BCE, he was concerned with the practices of an entire building culture (Moore and Wilson 2013). However, with the rise of the Renaissance some sixteen centuries later, Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture shifted the emphasis of judgment from whole building cultures to the singular works of individual architects. For the first time in history, excellence in building style and practice became associated with the genius of single individuals, rather than that of a people (Habraken and Teicher 2005). “Excellent” design succeeded in distinguishing elite commissioners rather than benefiting the public. The modern standard of design excellence, derived from Palladio onward, has been abstract and universal, too often devoid of local context and the nuances of place (Moore and Wilson 2013). The all-too-obvious problem with employing such narrow and exclusive criteria for judgment, as constructed in the Renaissance, is that the social and ecological conditions in which we build today have radically changed.

Where we can go: toward regenerative design

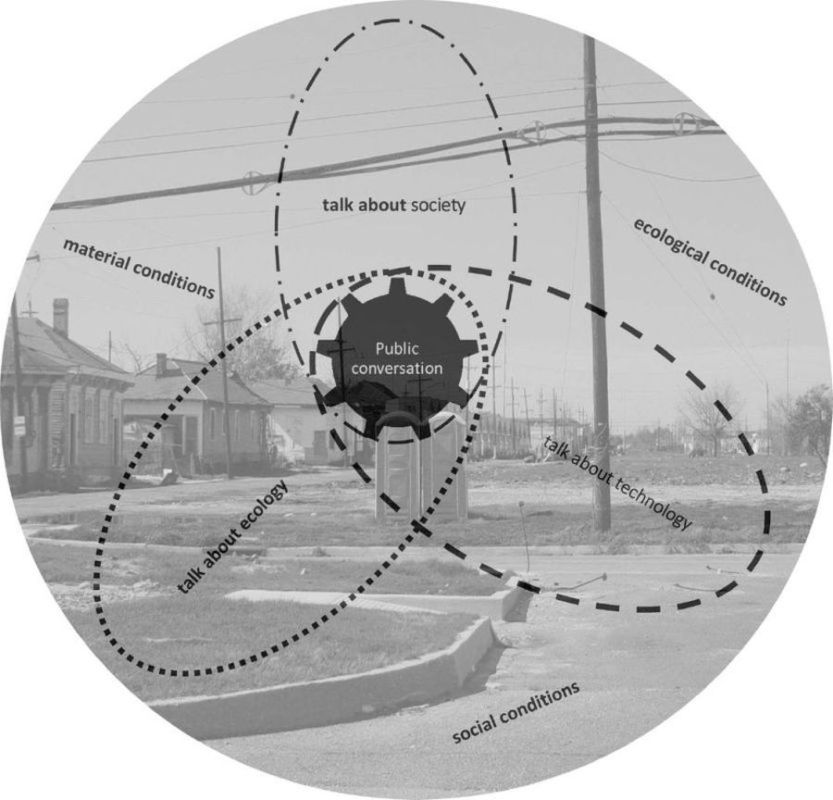

The good news appears to be that the high stakes of the current crisis of architectural judgment create an opportunity to transform previously entrenched patterns and practices. We support a growing number of leaders in the sustainable design discourse in calling for a new conversation focused on regenerative design, defined as “a collaborative, inclusive, place-based conversation and call to action for stakeholders in the built environment to create a built environment that supports the flourishing of life” (Moore and Walsh 2012). As envisioned in Figure 24.2, regenerative design views the co-evolution of social, technological, and ecological systems as an active and intentional process; humans consciously shape our social, technological, and ecological environments through conversation and have responsibility to do so in a way that supports (human and non-human) life (Cole 2012a).

FIGURE 24.2 Public conversation as a driver of changing social, ecological, and material conditions

Source: authors.

Regenerative design offers a powerful call for a new kind of architectural judgment grounded in four integrated public conversations:

• an ethical and aesthetic conversation to imagine a world where life flourishes;

• an inclusive conversation that engages diverse stakeholders and builds collective will;

• a place-based conversation that builds on strengths and considers consequences;

• a conversation that builds capacity for relational systems thinking.

Although modern aesthetics and science often appear to be at odds with each other, regenerative design holds that “things judged truly beautiful will in time be regarded as those that raised the human spirit without compromising human dignity or ecological functions elsewhere” or at another time (Orr 2006). This aesthetic implies an ethical imperative to protect and engage vulnerable human populations who are rarely included in public conversations about their home environments, and are disproportionately burdened by the economic and aesthetic pursuits of those with power and resources (Bullard et al. 2007; Moody 2012).

Inclusion of diverse stakeholders is also a strategic imperative in that it helps build (1) deeper collective knowledge of the whole system, and (2) the collective will among stakeholders required for sustained high performance of the building landscape, or region (Holden 2008; Innes and Booher 2010). When we fully acknowledge that buildings are co-evolving social, ecological, and technical systems, it becomes important to engage the people who inhabit and influence these systems now and in the future.

To engage diverse building inhabitants in a regenerative dialogue, it is important to build on the strengths of the particular place, as observed by Bob Berkebile (2012):

As more and more people struggle with the oppressive process of measuring or mitigating the incremental destruction of life that is typical in sustainable design practice, regenerative design turns this perspective on its ear and focuses instead on measuring the vitality and quality of life that is emerging in a place as it evolves to support life. Regenerative design allows people to see their role in creating or maintaining the conditions that are conducive to life.

This place-based regenerative dialogue enables inhabitants to see their own power in the existing systems and to embrace it by making new choices and enacting new commitments appropriate to their particular place. By focusing first on what people already love and are willing to protect, regenerative designers have been more successful in garnering sustained collective action than through problem-based approaches (Hoxie et al. 2012; Mang and Reed 2012). These strengths-based approaches draw on the literatures and practices of “asset-based community development” (Kretzmann and McKnight 1993), “appreciative inquiry” (Cooperrider and Whitney 2005), and “positive psychology” (Grant 2012).

A strong place-based conversation also considers the consequences of design choices for surrounding communities at multiple scales. Danielle Pieranunzi, Director of the Sustainable SITES Initiative, emphasized that “[i]t is essential that architecture not be judged in isolation without regard to how the site and community are impacted and how ecosystem services are protected or improved” (2012). While the LEED rating system has been criticized for failing to adequately consider performance of buildings post-occupancy (Miller 2012; Turner and Frankel 2008), regenerative design underscores the importance of multi-disciplinary post-occupancy performance evaluation at multiple scales (Moore and Walsh 2012).

The public conversation of regenerative design must also build capacity for relational, systems thinking in learning communities. The reductive, “best-practice” approach to assessment often used in conventional green building rating systems is no longer sufficient. The “objective” systems thinking conducted by “outside” observers intended to predict and control urban systems (Bordass and Leaman 2005) also fails to be enough. Stretching beyond best practices and mechanistic thinking, regenerative design calls for an active, engaged, and intuitive systems thinking that can embrace uncertainty, notice patterns, and accept responsibility for agency (Mang and Reed 2012). Since regeneration is an unfolding process and the definition of “sustainability” necessarily changes over time, the challenge of architectural judgment is ultimately to build the regenerative capacity of the people who will inhabit and manage the project in question rather than judge the artifact itself (Mang and Reed 2012).

Building such regenerative capacity also requires high levels of trust and reciprocity as well as collaborative leadership. To establish conditions for regenerative public conversation, Mang and Reed (2012) underscore the importance of self-reflection and self-actualization occurring concurrently with process design. As they put it, “the participatory and co-creative nature of a regenerative process also requires psychological and cultural literacy, and the ability to tap the latent creativity of a community by weaving broader sets of expertise and insight into the design process” (Mang and Reed 2012). Building common vision and collective will amongst diverse stakeholders requires leaders with exceptional emotional intelligence, enabling them to empathize with potential collaborators, build networks of trust, and create conditions safe enough for people to share their true intentions and nascent ideas (Goleman et al. 2012). In doing so, leaders can help stakeholder groups harness their untapped collective wisdom and creativity to generate context-appropriate solutions (Scharmer 2009). Unfortunately, the training of architects and planners rarely builds such relational intelligence or leadership skills. Too often students are trained to be distant experts who can use argumentation and graphic image-making to convince others of their own vision, but rarely are they prepared to enter into genuine dialogue with a client to build a collective or public vision.

FIGURE 24.3 Greensburg Regenerative Design Dialogue. In the wake of the disaster of an EF5 tornado, over 300 people gathered under a large, temporary circus tent on the east edge of town to share their ideas and create a unified community vision. The tent served as a space for community dialogue throughout the recovery process, hosting several design workshops, community meetings, and even Sunday morning church service.

Source: BNIM, © BNIM.

Exemplars: regenerative design in practice

Regenerative design is still a new area of scholarship and practice, but one with a solid foundation and broad opportunities for research, action, and education. Facilitating the kind of dialogue called for in this chapter is an important challenge. Thankfully, innovators have been experimenting in practice and are translating much of their tacit and empirical knowledge into more usable forms, through process guidelines, evaluation rubrics, rich case studies, and academic literature.

Two private firms, BNIM and REGENESIS have been leading contributors of their reflective practice to regenerative design scholarship. Bob Berkebile of BNIM celebrates the tremendous advances in community process over the past 20 years as a key to their successful community planning work. BNIM has refined an approach they call “a collaborative dialogue of discovery,” facilitated through public conversations. They have found that “when the residents, stakeholders and consultants come together as a collaborative community, a creative force is generated that produces miracles” and generates social learning as the lasting capacity for regenerative design and development (2012; Hoxie et al. 2012). BNIM’s work in Greensburg, Kansas, is a powerful example of their practice of regenerative design. After a devastating EF5 tornado in 2007, BNIM designed a regenerative public conversation through which Greensburg’s citizens chose to rebuild an economically, socially, and ecologically sustainable city. As shown in Figure 24.3, over 300 people gathered under a large, temporary circus tent to share their ideas and create a unified community vision. The tent served as a space for community dialogue throughout the recovery process, hosting several design workshops, community meetings, and even Sunday morning church service. The process itself helped generate the town’s capacity for regenerative design. United by a vision of creating a strong community devoted to family, fostering business, and working together for future generations, the Greensburg community chose to build their new K–12 school at the center of the community and to build it – and every other future public building – to the LEED-Platinum green building standard. This new LEED-Platinum school (see Figure 24.4) will help sustain the town’s regenerative capacity, as reflected by the observations of Darin Headrick, the school district’s superintendent:

FIGURE 24.4 Greensburg Regenerative Rebuild, LEED-Platinum high school. United by a vision of creating a strong community devoted to family, fostering business, working together for future generations, the Greensburg community chose to build their new K–12 school at the center of the community and to build it – and every other future public building – to the LEED-Platinum green building standard.

Source: BNIM, © Assassi.

Before the tornado, if you asked most of the high school kids about their plans for the future, they’d say the same thing, “I’m going to go away to college and never come back.” Now they say, “I’m going to go to college and then come back.” They see things here they can impact.

As the case of Greensburg shows, the process and practice of regenerative design helps people create places they love and are willing to steward for generations to come.

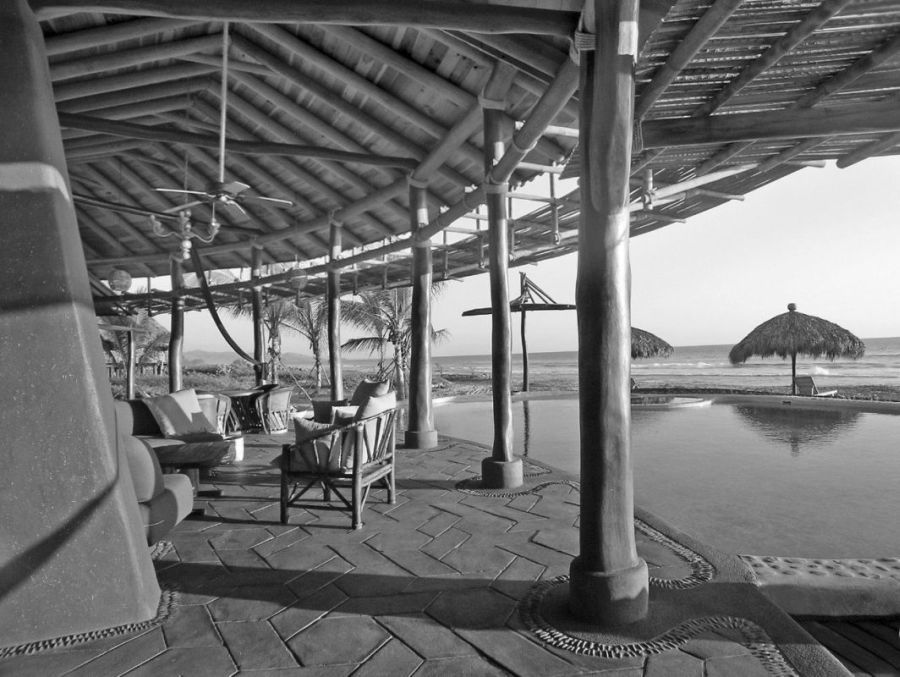

Drawing on similar approaches, REGENESIS has translated 16 years of reflection in practice into a regenerative methodology with a strong theoretical foundation (including Living Systems Thinking, permaculture, and developmental change processes). Drawing on research demonstrating the brain’s higher capacity to make sense of complexity through story-telling, they have developed a “Story of Place” methodology that has helped build regenerative capacity for their projects. One powerful example of their regenerative design practice is Playa Viva, a sustainable boutique vacation resort near Juluchuca, Mexico, situated on a beach among lush mangroves, ancient ruins, and the natural habitats of thousands of species. As part of the regenerative design process, project leaders convened a multi-disciplinary team of experts and interviewed the local community to learn about their aspirations and memories of the place and its changes over time. Drawing from the community’s local knowledge and the diverse team of experts, the team designed their beach resort to “revitalize and nurture local natural resources and the community, so they thrive in harmony and continually improve” (Leventhal, n.d.). Today, their luxurious resort lives lightly on the earth (see Figure 24.5), through provision of local, sustainable food sources, use of local materials and services, and design of structures that operate comfortably using minimal energy supplied by renewable energy sources such as solar arrays and solar thermal systems. Designing with community cultivation in mind, the resort enables guests to form new relationships with one another through a mix of private and public spaces, provides volunteer opportunities to meaningfully contribute to the surrounding community, and contributes through the Regenerative Trust, a 2 percent fee added to the total bill for all guests as a contribution to the social and environmental welfare of Juluchuca. By engaging the deep contextual knowledge of the community and the knowledge of disciplinary experts throughout the process, REGENESIS supported Playa Viva in creating a resort designed to support and enhance its very particular context while meaningfully engaging visitors from other places. With this and other successes from practice, REGENESIS joins the regenerative design movement in a call for process-based tools that empower context-specific, collaborative, and creative ecological design (Moore and Walsh 2012).

FIGURE 24.5 Regenerative tourism at Playa Viva. Regenerative resorts facilitate mutually beneficial relationships among guests, the surrounding ecosystem, and communities.

Source: courtesy of Playa Viva; photo by Randolph Langenbach.

FIGURE 24.6 Participatory process for the Potty Project. Tactile models and image cards helped resettlement community members engage in public conversations about sewerage infrastructure design.

Source: Julia King.

FIGURE 24.7 A decentralized sewerage system in the making. Following community dialogue, the sewerage design team installed shallow bore sewer pipes along the narrow streets to direct effluent from homes to the decentralized waste water treatment plant, with minimal disruption to the existing built environment.

Source: Julia King.

Responding to the need to bolster the capacity of the emerging community of practice in regenerative design, the United States Green Building Council (USGBC) retained a core team at BNIM to develop “REGEN” – an online “forum, a repository for place-based and systems-based information and a framework capable of stimulating dialogue among diverse practitioners and decision makers.” Still in its early development, REGEN reflects the kind of support system that will advance regenerative architectural judgment throughout the design and development cycle. Its greatest promise is expanding the conversation for regenerative design in a way that taps greater collective wisdom, will, and resources.

Two other promising process-oriented frameworks for architectural judgment featured in the Beyond LEED conference: LENSES (Living Environments in Natural, Social, and Economic Systems) and the SEED (Social Economic Environmental Design) network. Both programs foster inclusive and holistic public conversations about design of the built world through place-based, bottom-up approaches to an integrated design process. They share a commitment to developing a networked community of practitioners who are highly skilled process facilitators who consider social, ecological, and economic aspects of the built environment as they craft places. Both initiatives aim to empower innovative practitioners with sets of rich case studies, enabling them to learn through the lived experience of colleagues. SEED already supports its learning network with an online community equipped with online performance tracking and evaluation (Cole 2012b, 2012c; Moore and Wilson 2013; Plaut et al. 2012; SEED 2013). SEED also supports an annual awards program for projects that directly engage communities in design projects with significant social, economic, and environmental benefits.

One of the SEED 2014 winning projects, a decentralized sanitation system in Savda Gherva, a resettlement area outside of New Delhi, stands out both for its innovative community process and the ecologically and socially appropriate infrastructure it produced. Julia King, a doctoral student in architecture from the UK, engaged community members in a design workshop focused on sanitation. To overcome language and literacy constraints, King’s team provided image-based issue cards that allowed residents to prioritize their concerns and aspirations (see Figure 24.6). Further, to convey complex building and infrastructure designs simply, King used very simple representations of the existing variety of homes to convey how individual houses would be transformed with the arrival of the new sewerage infrastructure. Working with community members, local authorities, and infrastructure experts, the team built an off-grid, decentralized sanitation system that serves more than 1,500 people with minimal disruption to the existing built environment, at 25 percent less cost than a conventional sewer system. Shallow bore sewer pipes were placed along narrow streets and connected to a septic system located beneath a community park where waste water is cleaned and discharged (see Figure 24.7). For more information, see http://www.holcimfoundation.org/Projects/decentralized-sanitation-system-near-new-delhi-india.

Conclusion

Given the social, ecological, and economic challenges posed by the dominant practices of architecture and planning, architectural judgment can no longer afford to be a private conversation among social or professional experts (exclusive), nor strive for aesthetic ideals devoid of social or ecological context (narrow). Instead, architectural judgment must engage diverse stakeholders in public conversation that builds collective knowledge, finds meaning particular to the richness of place, and builds the capacity of the whole group for relational systems thinking. In order to construct a building culture that supports the flourishing of life, architectural judgment must marshal its two most powerful creative forces: language and the design of our built world. By harnessing the social functions and processes Mumford imagined – which are now developed more fully through research and practice in regenerative design – we can more powerfully generate an “effective symbiosis or a co-operative living together” (Mumford 1938). Our current challenge is to continue experimenting, documenting pilot projects for rich case studies, and building the capacity of an ever-expanding and history-shaping conversation.

References

Berkebile, R. (2012) “Promoting Obsolescence: A Journey Toward Regenerative Design.” University of Texas, Beyond LEED: Regenerative Design Symposium. February. http://soa.utexas.edu/beyondleed/PDFs/11.Berkebile.pdf

Bordass, B. and A. Leaman (2005) “Making Feedback and Post-Occupancy Evaluation Routine 1: A Portfolio of Feedback Techniques.” Building Research & Information 33(4): 347–52.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. R. Nice. London: Routledge.

Box, H. (2007) Think Like an Architect. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bullard, R. D., P. Mohai, R. Saha, and B. Wright (2007) Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: 1987–2007. Cleveland, OH: United Church of Christ Justice & Witness Ministries. http://www.ucc.org/assets/pdfs/toxic20.pdf

Capra, F. (2005) “Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability.” In M. K. Stone and Z. Barlow (eds), Ecological Literacy: Educating Our Children for a Sustainable World. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books, University of California Press.

Cole, R. J. (ed.) (2012a) “Regenerative Design and Development.” Special issue of Building Research & Information 40(1).

Cole, R. J. (2012b) “Regenerative Design and Development: Current Theory and Practice.” Building Research & Information 40(1): 1–6.

Cole, R. J. (2012c) “Beyond LEED: Embracing Holism, Engaging Complexity & Accepting Uncertainty.” University of Texas, Beyond LEED: Regenerative Design Symposium. February. http://soa.utexas.edu/beyondleed/PDFs/2.Cole.pdf

Cooperrider, D. L. and D. K. Whitney (2005) Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Davis, H. (2006) The Culture of a Building. New York: Oxford University Press.

Goleman, D., L. Bennett, and Z. Barlow (2012) Ecoliterate: How Educators Are Cultivating Emotional, Social, and Ecological Intelligence. New York: John Wiley.

Grant, G. B. (2012) “Transforming Sustainability.” Journal of Corporate Citizenship 46: 123–37.

Habraken, N. J. and J. Teicher (2005) Palladio’s Children: Essays on Everyday Environment and the Architect. New York: Routledge.

Holden, M. (2008) “Social Learning in Planning: Seattle’s Sustainable Development Codebooks.” Progress in Planning 69: 1–40.

Hoxie, C., R. Berkebile, and J. A. Todd (2012) “Stimulating Regenerative Development through Community Dialogue.” Building Research & Information 40(1): 65–80.

Innes, J. E. and D. E. Booher (2010) Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis.

Kretzmann, J. P. and J. McKnight (1993) Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets. Evanston and Chicago, IL: The Asset-Based Community Development Institute, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, distributed by ACTA Publications.

Leventhal, D. (n.d.) “Playa Viva: Regenerative Practices.” http://www.playaviva.com/sustainable-by-design/regenerative-practices/regenerate

Miller, C. S. (2012) “LEED: A Set-up For Sick Buildings? Is LEED Diamond the Answer?” University of Texas, Beyond LEED: Regenerative Design Symposium. February. http://soa.utexas.edu/beyondleed/PDFs/9.Miller.pdf

Moody, L. (2012) “Building for the Future: A Vision for Sustainable Communities.” University of Texas, Beyond LEED: Regenerative Design Symposium. February. http://soa.utexas.edu/beyondleed/PDFs/10.Moody.pdf

Moore, S. A. and E. A. Walsh (2012) “Beyond LEED.” Platform, Fall 2012. http://soa.utexas.edu/files/publications/platform_fall2012.pdf

Moore, S. A. and B. B. Wilson (2013) Questioning Architectural Judgment: The Problem of Codes in the United States. New York: Routledge.

Mumford, L. (1938) The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Orr, D. W. (2006) Design on the Edge: The Making of a High-Performance Building. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pieranunzi, D. (2012) “How SITESTM and an Ecosystem Services Framework Can Influence the Performance of Both Architecture and Landscape.” University of Texas, Beyond LEED: Regenerative Design Symposium. February. http://soa.utexas.edu/beyondleed/PDFs/7.Pieranuzi.pdf

Plaut, J. M., B. Dunbar, A. Wackerman, and S. Hodgin (2012) “Regenerative Design: The LENSES Framework for Buildings and Communities.” Building Research & Information 40(1): 112–22.

Scharmer, C. O. (2009) Theory U: Learning from the Future as It Emerges. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Ebooks Corporation Limited.

SEED (2013) “SEED: Social Economic Environmental Design.” http://www.seed-network.org/

Turner, C. and M. Frankel (2008) Energy Performance of LEED® for New Construction Buildings. Washington, DC: The New Building Institute for the U.S. Green Building Council. http://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=3930

The urban economist David Perry, former director of the Great Cities Initiative in Chicago, once offered a distinction between architects and planners: “When architects put something physical into the world, they think of their job as done. When planners put something into the world, they think of their job as just beginning” (Perry 2006). As the chapters in Part V help demonstrate, building performance evaluation is an ideal, integrative framework for architectural criticism. An integrative intellectual framework would extend the typical compositional and historical assessments of architecture to include its life in time and use, which would in turn expand the ethical compass of criticism to include a building’s impact on environment, health, and well-being. Such criticism would constitute a greater “inducement to involvement,” to borrow a phrase from the philosopher Richard Rorty – if “truth is what works,” then “the obvious question is whom does it work for?” (Rorty 2006). This broader problem field stands to strengthen the credibility and value of architecture, which in turn stands to transform the design methodologies that produce new subjects and objects of criticism.

When a French journalist asked Charles Eames, “What are the boundaries of design?” Eames famously answered, “What are the boundaries of problems?” (Eames 1972). Eames understood design as the arrangement of parts that best accomplishes a stated purpose; the confluence of evidence and intuition is the hallmark of the Eames ethos. I suggest two derivative properties of this ethos that might be enriched by building performance evaluation – suitability to context and modulation of waste. None of these qualities preclude the vast list of aesthetic attributes and meanings critics assign to newsworthy design.

The fourth epistemology

In The Marketplace of Ideas, Louis Menand describes three dominant modes of research driving knowledge production, based on three categories of engagement: disciplines that are interested in the way things are, disciplines that are interested in how people behave, and disciplines that are interested in what things mean – respectively empiricism, hermeneutics, and some combination of the two (Menand 2010). The kind of highly integrative built environment vocabularies suggested by contributors to this volume intimates a “fourth epistemology,” a hybrid universe of knowledge production based on poetic reasoning, empirical research, and creative practice. This fourth method of inquiry concentrates on the ratio of the way things are to the way they could be. Its aim is principled composition, defined as contextually suitable forms and systems that flow from design, planning, and production. Its practices are no less essential to social and cultural advancement than traditional science and the humanities, which this fourth epistemology both complements and completes. It significantly influences our response to the “wicked” problems of this century – energy, climate, the environment, urbanization, information, the economy, health, and social equity – not least in its capacity to frame time, enrich experience, reduce stress, improve health, stabilize habitat, and through its aesthetic responsibilities, engender greater and more productive self-awareness and self-fulfillment.

Other branches of the academic enterprise envy the integrative pedagogies of the design studio, for good reason. Ways of knowing that characterize studio experience embody Herbert Simon’s observation that “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones” (Simon 1996). A new approach to architectural criticism may reside here, by multiplying the value of diverse vocabularies among the variegated disciplines with responsibility for built environments, and by translating hybrid research into practice.

As the authors in Part V demonstrate, the suitability of a more thoughtful integration of coupled human and natural systems into the vocabularies of architectural criticism seems like an obvious and necessary advancement of knowledge. The habitual resistance of the educators and practitioners to integrated practice brings to mind David Foster Wallace’s commencement address at Kenyon College: “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’” (Wallace 2009).

What the hell is the construction industry? What the hell is real estate? What the hell is performance? Old habits may survive academic program review, accreditation standards, criteria for licensure, but they are not likely to survive the last recession and its seismic impact on practice. Harvard economist Kermit Baker confirms that the number of employees in US architecture firms declined nearly 30 percent from its peak in 2008 (Baker 2012). Few of these jobs are likely to return in the same form, if at all. According to a 2012 Georgetown University survey on the impact of the recession among a dozen or so different academic disciplines, architecture graduates suffered the highest rate of unemployment – 14 percent, worse even than fine arts majors (Rampell 2012). More recently, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported data on the change in the number of Bachelor’s degrees awarded among 42 fields of study over a 20-year period, between 1991 and 2011: construction trades ranked first, with a 1,267 percent increase over 20 years; architecture and related services ranked 35th, increasing just 1 percent, less even than English (Chronicle of Higher Education 2013). Now add to this the fact that the profession of architecture spends up to seven times more to accredit its professional degree programs and license its interns than the professions of engineering and law, which offer their graduates substantially greater earning power (Monti 2012–13). Keeping Baker’s and the Chronicle’s figures in mind, the future of the profession depends upon skillful management of the relationship between enrollment and employment. One remedy is to transform the public perception of the value of architectural knowledge from its primarily artistic and compositional fixations to a kind of expertise more directly connected to experience and human optimization.

Object versus event

The more we approach buildings as events, not objects, the more congenial the relationship between data and interpretation. The word “event” derives from Latin, eventus, from evenire, meaning “to result” or “to happen” – from ex-, “out of,” conjoined with venire, “to come.” Fixity and permanence are strictly human conceits; built environments are material and social events in a continuous state of becoming. This view has already proliferated in projects and writings at the margins of practice and the curriculum, where both avant-garde and built environment theory have adopted increasingly integrative methods. These emerging models tend to conceptualize design as a distributive responsibility networked in collaboration with interdependent and highly collaborative agents. Finance, construction, engineering, ecology, material science, public health, planning, and architecture – all these specializations converge in the context of problem fields requiring the coordination of data and specification at multiple scales, often simultaneously.

The 2013 repositioning initiative of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) testifies to the influence of this orientation, and helps account for AIA’s identification of four strategic priorities for the coming decade: resilience, materials, energy, and health (American Institute of Architects 2014). All four of these categories suggest a much greater emphasis on research, data, empirical analysis, and building performance; and all four suggest a deeper integration within the Institute’s historical commitments to design. The message is clear: design excellence must now exhibit measurable attributes that account for energy consumption, environmental integrity, carbon management, context, and health impacts. By focusing on the built environment as a continuously unfolding event inseparable in its molecular and systemic constitution from the events that surround it, architectural criticism can help shift concern from how a building looks to how it is made and to how it behaves over time. The authors in Part V and this entire book aim to reassess the relationship between good looks and good design through the lens of good performance, and to explore the effects this shift might have on our relevance and effectiveness in a precipitously uncertain future.

References

American Institute of Architects (2014) “Progress Report 2014.” http://www.aia.org/about/repositioning/index.htm.

Baker, K. (2012) Presentation to the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Board of Directors, Boston (from notes by the author).

Chronicle of Higher Education (2013) “Change in Number of Bachelor’s Degrees Awarded by Field of Study, 1991–2011.” Chronicle of Higher Education Almanac 2013–14, August 23.

Eames, C. (1972) “Design Q&A.” In The Films of Charles & Ray Eames. Chatsworth, CA: The Eames Office.

Menand, L. (2010) The Marketplace of Ideas. New York: W. W. Norton.

Monti, M. (2012–13) “Is Architectural Education Today Sufficient to Prepare Tomorrow’s Practitioners?” [panel presentation]. Conversations on Architectural Education and the Future of the Profession. University of Maryland, March 1.

Perry, D. (2006) In conversation with the author.

Rorty, R. (2006) “Toward a Postmetaphysical Culture.” In Take Care of Freedom and the Truth Will Take Care of Itself: Interviews with Richard Rorty, ed. E. Mendieta. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 46–55.

Simon, H. A. (1996) The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wallace, D. F. (2009) This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life. New York: Little, Brown.